扩展功能

文章信息

- 朴弋戈, 唐业忠, 陈勤

- PIAO Yige, TANG Yezhong, CHEN Qin

- 猎物体温差异对短尾蝮捕食注毒量影响

- Influence of Prey Temperature on Venom Expenditure of Gloydius brevicaudus in Predatory Bite

- 四川动物, 2022, 41(2): 168-174

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2022, 41(2): 168-174

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20210406

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2021-11-21

- 接受日期: 2022-01-24

2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

毒液作为毒蛇的鉴别特征,是由多种酶、多肽等组成的混合液体(Elliott,1978;Iwanaga & Suzuki, 1979),主要用于制服猎物、完成捕食以及进行防御等(Hayes et al., 2002;Kerkkamp et al., 2017)。自然状态下,尽管毒腺内的毒液处于排出与分泌的动态平衡中,其在一定时间内仍是一种有限且重要的资源(Willemse et al., 1979;McCue,2006)。因此,曾有研究者推测毒蛇可能具有根据猎物的差异衡量并主动控制其注毒量的能力(Allon & Kochva, 1974;Hayes,1995;Hayes et al., 1995)。

蝮亚科Crotalinae物种约占毒蛇物种数的1/3(Zaher et al., 2019),具有高度敏感的热感应器官——颊窝,可感知低至0.003 ℃的温度变化(Bullock & Diecke, 1956;Buning et al., 1981)。这一感官使蝮蛇可以获取环境中的热信息,在黑暗环境中捕食恒温动物时具有重要作用(Kardong & Mackessy, 1991;Krochmal & Bakker, 2003)。在捕食行为中,除了视觉、嗅觉和振动觉等感官系统外,蝮蛇可先凭借红外感知系统对猎物进行识别和定位,再利用毒液使其丧失活动能力(乃至死亡)以完成取食。颊窝与毒液系统在蝮蛇捕食行为中存在明确的承接关系。在捕食不同体温的猎物过程中,猎物体温的差异可能表征种类和状态,而这些差异是否影响攻击时的注毒量则有待证明。

本研究对短尾蝮Gloydius brevicaudus投喂经人为控制温度的死亡乳鼠,模拟其在自然环境中多样化猎物的温度差异。通过记录捕食行为并测定注毒量,探讨猎物体温对短尾蝮捕食注毒量的影响。

1 材料与方法 1.1 实验动物短尾蝮是广泛分布于我国的一种蝮亚科蛇类(赵尔宓,2006),个体相对较小,在蝮蛇行为学、生理学研究中可操作性强。本实验选取7条实验室饲养的短尾蝮亚成体(3条雄性,4条雌性),吻肛长(36.37±2.51) cm,尾长(5.24±0.60) cm,体质量(36.0±8.6) g。

实验动物均单独饲养于饲养箱(长32 cm×宽22 cm×高19 cm)中,箱内垫料为报纸,放置一水盆并保持净水供应,同时放置一爬虫躲避穴(长23 cm×宽16.5 cm×高7.5 cm)供蛇隐藏。饲养房内设定室温为25 ℃,实际记录室温为(25.41±0.32) ℃,光周期为12 h∶ 12 h,光照时间为08∶ 00—20∶ 00。实验期间短尾蝮均仅在实验中进食。

使用冷冻乳鼠作为食物,所有乳鼠均为初生小鼠Mus musculus(约2日龄昆明小鼠,不区分性别),体质量(2.064±0.384) g。实验前,每10只用一洁净自封袋包装,以混合不同乳鼠之间的气味。为保证温度均衡,封闭后的自封袋浸没于水浴锅中化冻90 min,使乳鼠达到设置温度。按照预设猎物体温,设置为高温组(34.00 ℃±0.18 ℃)、中温组(26.01 ℃±0.25 ℃)和低温组(19.57 ℃±1.40 ℃)。

1.2 实验方案对每条短尾蝮样本,分别进行高、中、低3个温度梯度的模拟“猎物”捕食实验。每个温度梯度进行2次重复,因此每条蛇完成6次捕食实验。依据多数蝮亚科蛇类夜行性规律(Oliveira & Martins, 2001;Sawant & Shyama, 2007),所有实验均在19∶ 30—22∶ 00进行。为消除进食后食欲下降的影响,实验间隔时间均超过7 d。为规避环境变化对动物产生的应激影响,所有实验均在个体所在饲养箱内进行(Glaudas,2004);实验场所即日常饲养房,维持动物的正常饲养温度。同时,使用双层黑色塑料袋和金属框架制作了一个矩形围帐(长72 cm×宽70 cm×高70 cm),实验时将饲养箱置于其中以减少外界环境的干扰。为避免不同实验日期伴随的环境系统误差以及顺序效应,个体和条件以随机顺序进行测试。

1.3 操作流程单次实验流程如下:实验时将饲养箱置于围帐中,手动打开箱盖后,取出躲避穴,给予无打扰的3 min适应时间(Mori et al., 2016)。适应时间末期,取出加温至实验条件的解冻乳鼠,搽拭去多余水分后用分析天平(JA1003A,精度1 mg,准确度Ⅱ级;精天电子仪器有限公司,上海)称重。使用红外测温仪(HT-866,广州市宏诚集业电子科技有限公司,广州)聚焦于乳鼠腹部距离5 cm处,待示数稳定后读取温度示数。随后,使用白色缝纫棉线(长度75 cm)一侧线头以活扣固定乳鼠,另一线头连接于金属蛇钩,操作蛇钩使乳鼠晃动于蛇头部前方(Hayes & Hayes, 1993;Araujo & Martins, 2007)约5 cm处,以模拟猎物的运动。至蛇发动攻击行为停止实验,或计时2 min结束后停止实验,记录实验时间与动物吐舌次数。取下乳鼠置于分析天平上称量以计算注毒量,舍弃无法判明注毒量的数据(Kochva,1960)。所有称量均连续操作3次,取平均值。实验结束后,将蛇放回躲避穴,同时放入乳鼠,记录实验个体是否正常进食。捕食过程使用佳能EOS 80D以50帧/s俯视拍摄记录。

1.4 统计分析因部分数据不符合正态分布,主要采用非参数检验方法。显著性水平设置为α=0.05。所有统计分析均采用SPSS进行。所有数据均使用x±SD进行描述。

采用Mann-Whitney U检验比较各组内2轮实验间参数的差异,采用Kruskal-Wallis检验分析比较多组样本间的猎物体温、实验时间、吐舌次数和注毒量的差异。

采用Spearman相关性分析处理各主要变量与注毒量的相关性。在进行形态学变量相关性分析时,雌性和雄性分别以数字1和2表示。

2 结果与分析共获得42次有效测试数据,其中表现明显捕食攻击30次,无攻击5次(均来自9号),试图直接进食7次。实际记录最大排毒量17 mg,最小1 mg,均值6.76 mg。

2.1 差异性分析3组组内2轮实验之间短尾蝮捕食注毒量均无显著性差异(高温组:U=19.000,P=0.537;中温组:U=18.000,P=0.662;低温组:U=12.000,P=0.662)。

虽然实验中各组猎物体温均由水浴锅控制于预定温度,表现出较小的变化(中温组和低温组变异系数分别为0.96%和7.15%),但组内2轮实验的猎物体温呈现出显著性差异(高温组:U=15.000,P=0.259;中温组:U=44.500,P=0.007;低温组:U=48.500,P=0.001),将3个温度梯度组的各2轮重复实验划分为6组:高温组1、高温组2、中温组1、中温组2、低温组1和低温组2。在猎物体温方面,低温组1与高温组1(P<0.001)和高温组2(P<0.001)、低温组2与高温组1(P=0.001)和高温组2(P=0.006)之间的差异极显著(H=38.643,df=5),低温组1与中温组2具有显著性差异(P=0.029)。6组动物的吐舌次数(H=1.279,df=5,P=0.937)、实验时间(H=3.546,df=5,P=0.616)之间均无显著差异,且6组注毒量之间的差异不显著(H=4.723,df=5,P=0.451)。

2.2 相关性分析猎物体温与室温表现出显著相关性(r=-0.359,P=0.019),但因为猎物体温是人为设定,因此该相关性不被采用。吐舌次数与实验时间存在极显著相关性(r=0.756,P<0.001),注毒量与猎物体温无显著相关性(r=0.007,P=0.968;表 1)。

| 相关性 Correlation |

室温 Room temperature |

猎物体温 Prey temperature |

注毒量 Venom amount |

吐舌次数 Tongue flickers |

实验时间 Experiment time |

|

| 室温 | r | 1.000 | -0.359* | 0.398* | 0.055 | 0.039 |

| P | 0.019 | 0.022 | 0.766 | 0.831 | ||

| 猎物体温 | r | -0.359* | 1.000 | 0.007 | 0.034 | 0.111 |

| P | 0.019 | 0.968 | 0.852 | 0.537 | ||

| 注毒量 | r | 0.398* | 0.007 | 1.000 | 0.241 | 0.072 |

| P | 0.022 | 0.968 | 0.247 | 0.725 | ||

| 吐舌次数 | r | 0.055 | 0.034 | 0.241 | 1.000 | 0.756** |

| P | 0.766 | 0.852 | 0.247 | <0.001 | ||

| 实验时间 | r | 0.039 | 0.111 | 0.072 | 0.756** | 1.000 |

| P | 0.831 | 0.537 | 0.725 | <0.001 | ||

| 注Notes: *P<0.05,* * P<0.01;下同the same below | ||||||

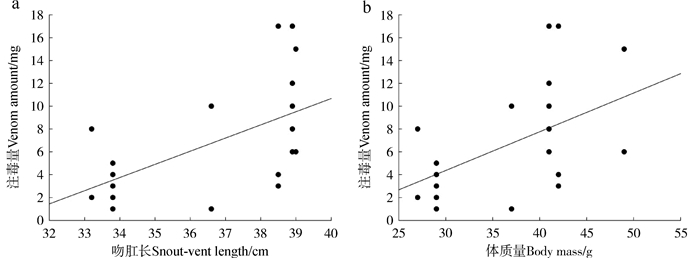

体质量与吻肛长(r=0.901,P<0.001)和尾长(r=0.559,P<0.001)皆具有极显著相关性,吻肛长与尾长极显著相关(r=0.464,P=0.002)。注毒量与体质量显著相关(r=0.506,P=0.019);与吻肛长极显著相关(r=0.595,P=0.004;表 2;图 1)。

| 相关性 Correlation |

体质量 Body mass |

吻肛长 Snout-vent length |

尾长 Tail length |

性别 Sex |

注毒量 Venom amount |

|

| 体质量 | r | 1.000 | 0.901** | 0.559** | 0.000 | 0.506* |

| P | <0.001 | <0.001 | 1.000 | 0.019 | ||

| 吻肛长 | r | 1.000 | 0.464** | <0.001 | 0.595** | |

| P | 0.002 | 1.000 | 0.004 | |||

| 尾长 | r | 1.000 | -0.144 | -0.002 | ||

| P | 0.362 | 0.993 | ||||

| 性别 | r | 1.000 | -0.032 | |||

| P | 0.891 | |||||

| 注毒量 | r | 1.000 | ||||

| P |

|

| 图 1 注毒量与吻肛长(A)和体质量(B)之间的相关性 Fig. 1 Relationship between snout-vent length (A), body mass (B) and venom amount |

| |

本实验通过人为操作使小鼠乳鼠达到不同的温度,模拟自然状态下不同体温的猎物,主要关注短尾蝮的注毒量是否因猎物体温不同而表现差异。结果显示,6个温度组短尾蝮捕食注毒量均不具有统计学差异。

在相关性分析中,体质量与吻肛长和尾长均有极显著相关性,吻肛长与尾长极显著相关;这一结果符合蛇类形态学特征,即同一种内,较大的蛇表现为长度更长、体质量更大。实验中,短尾蝮吐舌次数与实验时间极显著相关。因实验时间为从提供乳鼠开始计时至短尾蝮扑咬攻击停止计时,实验时间反映出实验个体面对“猎物”的时间。该结果符合蝮蛇的捕食行为特征:攻击前持续吐舌获取猎物信息,攻击时无吐舌行为,攻击后该行为用于追踪注毒后逃逸的猎物(Chiszar et al., 1982)。同时,实验中捕食注毒量与体质量表现出显著相关性,注毒量和吻肛长极显著相关。尽管早期关于毒蛇体型与注毒量的研究仅提供了模糊的结论(Gennaro et al., 1961;Morrison et al., 1983),但Herbert(1998)明确了同一种内体型与注毒量的正相关性。目前已证实的诸多影响因素中,体型是影响同一种内注毒量的主要因素(Hayes et al., 2002)。国内对人工养殖尖吻蝮Deinagkistrodon acutus的研究亦报道了相似的结果(黄松等,2004)。

毒液具有储存限制、代谢成本及其耗竭后的生态代价,是一种珍贵的资源(McCue,2006;Smith et al., 2014)。因此,衡量毒液、合理分配毒液使用的能力(毒液认知)被认为在有毒动物的进化过程中具有适应意义。目前研究已经证明,多种有毒动物具有根据不同情况调整注毒量的能力(Boevé et al., 1995;Hayes et al., 1995)。随着研究种类的不断增加,更多有毒动物极可能被证实具有这样的能力(Hayes et al., 2002)。

Hayes等(2002)研究指出,体温较高的变温动物活动性更强(逃逸能力更强),在测试中表现为死亡更快。因此毒蛇在捕食不同体温的变温动物时,可能需要采取不同的注毒策略,分配不同的注毒量。这一推测对于蝮亚科蛇类尤其具有意义:蝮蛇的颊窝在捕食恒温动物时提供了显著的优势(Embar et al., 2018),而这一器官在捕食变温动物时起到怎样的作用却并不明确。本研究关注短尾蝮能否根据猎物体温差异调整注毒量。由于具有高度的敏感性(Bullock & Diecke,1956;Buning et al., 1981),在面对不同温度的猎物时,蝮蛇无疑能够通过颊窝感知其体温差异。本实验中3组组间温差约8 ℃,而注毒量却未表现出显著的组间差异。因此推测,温度差异可能并不会引起短尾蝮对猎物表现出差异化的注毒量。

尽管已有研究使用线牵引刺激物的方式进行行为学探究(Hayes & Hayes,1993;Araujo & Martins,2007),但该模式并不能完全模拟小型啮齿类的正常活动状态。本实验中使用的猎物为化冻乳鼠,而实验所用的短尾蝮日常均使用活体小鼠喂食,活体小鼠与线牵引下乳鼠的行动状态的差别可能会影响蛇对猎物的判断。此外,虽然使用了矩形围帐遮蔽周围环境,但短尾蝮仍能从围帐上方观察到实验人员,实验过程中亦存在个体抬头注意实验人员所处方向的行为。因此,尽管未见明显的防御行为,人为干扰可能影响了短尾蝮,使其表现出对乳鼠的捕食行为和对人员的防御行为的权衡。在这种非自然状态下,短尾蝮可能表现出扑咬攻击时单一化或最大化的注毒量,混淆了实验结果。6组实验之间,短尾蝮吐舌次数与实验时间均无显著差异。实验完成后,以乳鼠投喂实验个体,除9号个体前4次实验连续未进食和14号仅1次未进食外(共5次),其余个体均连续进食,拒食现象并不常见。在进食37次中,30次均存在明显扑咬攻击,表现出正常的捕食行为。因此,猎物运动状态的差异和人为操作的因素虽不能排除,但对实验组的捕食过程影响应较小,未造成组间差异。

由于日常捕食的猎物种类显著影响了蛇类对猎物气味的偏好(Gove & Burghardt,1975),而几乎所有实验室饲养的蝮亚科蛇类均使用实验小鼠或大鼠Rattus norvegicus作为食物(Murphy et al., 1994),因此本实验使用人为控制温度的乳鼠。尚无研究指出蛇类能否通过气味区分恒温猎物与变温猎物。在捕食蛙类、蜥蜴等活体变温动物的行为中,短尾蝮乃至其他蝮亚科蛇类是否具有根据猎物体温调整注毒量的能力仍有待进一步探究。

基于目前的结果,我们谨慎地提出以下结论:在捕食小型哺乳类猎物的行为中,短尾蝮并不会根据猎物体温调整排毒量。

黄松, 程瑾, 黄接棠. 2004. 尖吻蝮(Deinagkistrodon acutus)生长过程不同时期排毒量及蛇毒组分的变化[J]. 四川动物, 23(3): 287-289. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7083.2004.03.032 |

赵尔宓. 2006. 中国蛇类上册[M]. 合肥: 安徽科学技术出版社.

|

Allon N, Kochva E. 1974. The quantities of venom injected into prey of different size by Vipera palaestinae in a single bite[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology, 188(1): 71-75. DOI:10.1002/jez.1401880108 |

Araujo MS, Martins M. 2007. The defensive strike of five species of lanceheads of the genus Bothrops (Viperidae)[J]. Brazilian Journal of Biology, 67(2): 327-332. DOI:10.1590/S1519-69842007000200019 |

Boevé J, Kuhn-Nentwig L, Keller S, et al. 1995. Quantity and quality of venom released by a spider (Cupiennius salei, Ctenidae)[J]. Toxicon, 33(10): 1347-1357. DOI:10.1016/0041-0101(95)00066-U |

Bullock TH, Diecke FPJ. 1956. Properties of an infrared receptor[J]. The Journal of Physiology, 134(1): 47-87. DOI:10.1113/jphysiol.1956.sp005624 |

Buning TDC, Terashima SI, Goris RC. 1981. Crotaline pit organs analyzed as warm receptors[J]. Cellular & Molecular Neurobiology, 1(3): 271-278. |

Chiszar D, Andren C, Nilson GOR, et al. 1982. Strike-induced chemosensory searching in Old World vipers and New World pit vipers[J]. Animal Learning & Behavior, 10(2): 121-125. |

Elliott WB. 1978. Chemistry and immunology of reptilian venoms[M]//Gans C, Pough FH. Biology of the reptilia. New York: Academic Press.

|

Embar K, Kotler BP, Bleicher SS, et al. 2018. Pit fights: predators in evolutionarily independent communities[J]. Journal of Mammalogy, 99(5): 1183-1188. DOI:10.1093/jmammal/gyy085 |

Gennaro JF, Leopold RS, Merriam TW. 1961. Observations on the actual quantity of venom introduced by several species of crotalid snakes in their bite[J]. Anatomical Record, 139: 303. |

Glaudas X. 2004. Do cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) habituate to human confrontations?[J]. Southeastern Naturalist, 3(1): 129-138. DOI:10.1656/1528-7092(2004)003[0129:DCAPHT]2.0.CO;2 |

Gove D, Burghardt GM. 1975. Responses of ecologically dissimilar populations of the water snake Natrix s. sipedon to chemical cues from prey[J]. Journal of Chemical Ecology, 1(1): 25-40. DOI:10.1007/BF00987718 |

Hayes WK. 1995. Venom metering by juvenile prairie rattlesnakes, Crotalus v. viridis: effects of prey size and experience[J]. Animal Behaviour, 50(1): 33-40. DOI:10.1006/anbe.1995.0218 |

Hayes WK, Hayes DM. 1993. Stimuli influencing the release and aim of predatory strikes of the Northern Pacific rattlesnake (Crotalus viridis oreganus)[J]. Northwestern Naturalist, 74(1): 1-9. DOI:10.2307/3536574 |

Hayes WK, Herbert SS, Rehling GC, et al. 2002. Factors that influence venom expenditure in viperids and other snake species during predatory and defensive contexts[M]//Schuett GW, Hoggren M, Douglas ME, et al. Biology of the vipers. Utah: Eagle Mountain Publishing.

|

Hayes WK, Lavín-Murcio P, Kardong KV. 1995. Northern Pacific rattlesnakes (Crotalus viridis oreganus) meter venom when feeding on prey of different sizes[J]. Copeia, 1995(2): 337-343. DOI:10.2307/1446896 |

Herbert SS. 1998. Factors influencing venom expenditure during defensive bites by cottonmouths (Agkistrodon piscivorus) and rattlesnakes (Crotalus viridis, Crotalus atrox)[D]. Loma Linda: Loma Linda University.

|

Iwanaga S, Suzuki T. 1979. Enzymes in snake venomedition[M]//Lee CY. Snake venoms. Berlin: Springer.

|

Kardong KV, Mackessy SP. 1991. The strike behavior of a congenitally blind rattlesnake[J]. Journal of Herpetology, 25(2): 208-211. DOI:10.2307/1564650 |

Kerkkamp HMI, Casewell NR, Vonk FJ. 2017. Evolution of the snake venom delivery system[M]//Gopalakrishnakone P, Malhotra A. Evolution of venomous animals and their toxins. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media.

|

Kochva E. 1960. A quantitative study of venom secretion by Vipera palaestinae[J]. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 9(4): 381-390. DOI:10.4269/ajtmh.1960.9.381 |

Krochmal AR, Bakken GS. 2003. Thermoregulation is the pits: use of thermal radiation for retreat site selection by rattlesnakes[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 206(15): 2539-2545. DOI:10.1242/jeb.00471 |

McCue MD. 2006. Cost of producing venom in three North American pitviper species[J]. Copeia, 2006(4): 818-825. DOI:10.1643/0045-8511(2006)6[818:COPVIT]2.0.CO;2 |

Mori A, Jono T, Takeuchi H, et al. 2016. Morphology of the nucho-dorsal glands and related defensive displays in three species of Asian natricine snakes[J]. Journal of Zoology, 300(1): 18-26. DOI:10.1111/jzo.12357 |

Morrison JJ, Pearn JH, Charles NT, et al. 1983. Further studies on the mass of venom injected by elapid snakes[J]. Toxicon, 21(2): 279-284. DOI:10.1016/0041-0101(83)90012-0 |

Murphy JB, Adler K, Collins JT. 1994. Captive management and conservation of amphibians and reptiles[M]. Cleveland: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles.

|

Oliveira ME, Martins M. 2001. When and where to find a pitviper: activity patterns and habitat use of the lancehead, Bothrops atrox, in central Amazonia, Brazil[J]. Herpetological Natural History, 8(2): 101-110. |

Sawant NS, Shyama SK. 2007. Habitat preference of pit vipers along the western ghats (Goa)[M]//Desai PV, Roy R. Diversity and life processes from ocean and land. Goa: Goa University.

|

Smith MT, Ortega J, Beaupre SJ. 2014. Metabolic cost of venom replenishment by prairie rattlesnakes (Crotalus viridis viridis)[J]. Toxicon, 86: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.04.013 |

Willemse GT, Hattingh J, Karlsson RM, et al. 1979. Changes in composition and protein concentration of puff adder (Bitis arietans) venom due to frequent milking[J]. Toxicon, 17(1): 37-42. DOI:10.1016/0041-0101(79)90253-8 |

Zaher H, Murphy RW, Arredondo JC, et al. 2019. Large-scale molecular phylogeny, morphology, divergence-time estimation, and the fossil record of advanced caenophidian snakes (Squamata: Serpentes)[J/OL]. PLoS ONE, 14(5): e0216148[2021-09-01]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216148.

|

2022, Vol. 41

2022, Vol. 41