扩展功能

文章信息

- 张凡梦, 鄢冉, 刘恣妍, 夏灿玮

- ZHANG Fanmeng, YAN Ran, LIU Ziyan, XIA Canwei

- 北京城区麻雀的逃逸距离及其影响因素

- Factors Influencing the Escape Distance of Tree Sparrows in Beijing City

- 四川动物, 2021, 40(2): 160-168

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2021, 40(2): 160-168

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20200327

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2020-08-22

- 接受日期: 2021-01-11

城市化是从相对无人为干扰的自然生境向人类活动占主导的城市生境的过渡(Sala et al., 2000;Lowry et al., 2013)。随着全球工业和经济的飞速发展,城市化进程正以前所未有的速度推进,其特点是:人造景观,尤其是建筑物和硬化的道路,取代自然景观(Sala et al., 2000)。城市化进程随着世界人口的增多而加快,将有更多土地被改造以满足人类需求(Luck,2007)。城市化进程中,植被结构和组成的变化,以及人类活动(行人、车辆、噪音污染、饲养宠物和家畜)的干扰,已影响到野生动物的生存(Schlesinger et al., 2008;Parris & Schneider,2009)。生物多样性在城市化程度高且人口密集的地区趋于减少(Clergeau,2006;Huang et al., 2010)。但少数野生动物能够适应城市生境,对人工景观和人为干扰表现出更大的耐受性,甚至种群数量大幅增加,成为城市生境的优势物种(Clergeau,2006)。对这些物种的研究有助于了解野生动物对城市生境的适应机制(Slabbekoorn & Ripmeester,2008;Lowry et al., 2013)。张凡梦等:北京城区麻雀的逃逸距离及其影响因素

相比栖息于自然生境的同类或近缘种,适应城市生境的物种在形态、行为、生理、遗传上都会有相应的变化(Slabbekoorn & Ripmeester,2008;Cardoso,2014)。其中,行为调节是在城市化过程中促进野生动物与人类共存的直接因素(Lowry et al., 2013;Sol et al., 2013)。在面对捕食风险时,动物会采取反捕食策略以延续个体的生存,如,逃逸、伪装、物理防御、化学防御、选择天敌较少的生境栖息、避开天敌活动的时段(Cooper & Blumstein,2015)。其中,逃逸行为是鸟类最常用的反捕食策略(蒋一婷,丁长青,2014;方小斌等,2017)。逃逸行为降低了动物被捕食的风险,但在移动过程中增加了能量的消耗,并减少了觅食和休憩的时间(Dowling & Bonier,2018)。逃逸距离(鸟类在做出行为改变时距危险源的距离)受自然选择的优化,以在降低捕食风险和减少能量消耗之间做出权衡(Ydenberg & Dill,1986;Cooper & Frederick,2007)。目前已有超过3 000种鸟类的逃逸距离得到了量化(Sol et al., 2018)。相比于自然生境的鸟类,城市生境的鸟类有更短的逃逸距离(Møller,2008)。这有助于减少鸟类频繁地逃逸,降低受到的人为活动影响,从而有利于其在城市生境中栖息(Møller,2008;Sol et al., 2018)。

本研究对北京城区麻雀Passer montanus的逃逸距离进行研究,探讨影响城市鸟类逃逸距离的因素。麻雀隶属于雀科Passeridae麻雀属,广布于欧洲、亚洲和非洲,并被引入美洲和澳洲(阮向东,1989)。麻雀是城市生境的优势鸟类(张淑萍等,2006)。相比栖息于自然生境的同属鸟类,栖息于城市生境的麻雀有更短的逃逸距离(Møller,2008;Dowling & Bonier,2018)。在城区的不同微生境中,麻雀的逃逸距离也表现出明显的差异(王彦平等,2004;叶淑英等,2013;潘汝南等,2018;鲍明霞等,2019)。本研究在量化麻雀逃逸距离的基础上,探讨麻雀群体大小、生境中猫的数量、行人数量、绿化比率和到市中心距离对麻雀逃逸距离的影响。大群体有助于发现威胁源,从而更早做出反应,同时也降低了单只个体承受的风险(Stankowich & Blumstein,2005)。猫Felis catus是城市鸟类的重要捕食者(Beckerman et al., 2007),可造成鸟类行为的改变(如减少鸟类在低处活动的时间)(Møller,2011),从而影响到鸟类的逃逸行为。行人数量和绿化比率分别反映了人为干扰的强度和景观改变的程度(Cooper,2003;Samia et al., 2015),从而影响到栖息在城市生境中的鸟类。北京城市化是由中心向四周发展(艾伟等,2008),到市中心距离可近似反映从自然生境转变为城市生境的时间长度,从而反映城市化对野生动物影响的累积效应。本研究探讨上述5个影响因素,以加深对城市鸟类逃逸距离在种内变异的了解。

1 数据与方法 1.1 研究地点本研究于2019年夏季(7月2日—8月31日)在29个研究地点量化麻雀的逃逸距离,涉及14个公园(奥林匹克森林公园、北海公园、朝阳公园、北京植物园、地坛公园、海淀公园、景山公园、陶然亭公园、天坛公园、香山公园、颐和园公园、玉渊潭公园、中山公园、紫竹院公园)和15个高校(北京大学、清华大学、北京理工大学、中国农业大学、中央财经大学、中国人民大学、对外经济贸易大学、北京科技大学、北京林业大学、中国地质大学、中国传媒大学、北京邮电大学、北京航空航天大学、华北电力大学、北京第二外国语学院)。麻雀是北京城区公园和高校的常见鸟类(潘超,郑光美,2003;张淑萍等,2006)。在上述地点开展研究,便于获得充足的样本量;且生境较为开阔,便于观察和量化麻雀的逃逸距离。此外,上述地点有明确的边界,便于生境变量的量化。

1.2 数据收集采用人类靠近鸟类是获取鸟类逃逸距离的常用方法(Tatte et al., 2018;Blumstein,2019)。虽然人类不是鸟类的主要捕食者,但鸟类对人类做出反应的距离可以近似替代鸟类对自然界捕食者的逃逸距离(Møller et al., 2008;Blumstein et al., 2016)。当实验对象周边100 m范围内无猛禽、黄鼬Mustela sibirica、猫等捕食者出现,且研究者是距离实验对象最近的行人时,开始实验。当观察到的麻雀数量超过1只时,任选其中的1只作为实验个体。研究者正对实验个体步行靠近,直至实验个体飞离。利用激光测距仪(保时安电子,型号:CS600),记录警戒距离(实验个体首次表现出警戒行为时,如,抬头环视、凝视研究者、跳跃远离,其与研究者之间的直线距离)、惊飞距离(实验个体飞离时,其与研究者之间的直线距离)和飞逃距离(实验个体飞离的起始位置到首次停落位置之间的直线距离)。警戒距离、惊飞距离和飞逃距离均是鸟类逃逸距离的组成部分(Cooper & Blumstein,2015;Tatte et al., 2018)。后文中强调这3个距离之间的差异时,将对警戒距离、惊飞距离、飞逃距离分别介绍,否则统称为逃逸距离。

每个研究地点进行2 d的观察。同一天观察的相邻2只个体之间的距离至少间隔50 m,以减少假重复(单只个体被当做多只个体进行多次观测)的可能性。实验个体均为麻雀成鸟(通过羽色与幼鸟区分),以避免年龄对逃逸距离的影响(张谦益等,2019)。性别对鸟类的逃逸距离会产生影响(Møller et al., 2016),但由于从体型和羽色上均不宜区分麻雀的性别(胥帅帅等,2018),故本研究未记录实验个体的性别。

实验过程中记录麻雀的数量用于反映群体的大小。实验个体飞离后,记录实验个体飞离位置周边30 m内3 min内的行人数量,做为人为干扰的强度。在每个研究地点选择30个相邻距离间隔100 m的样点,记录样点周边50 m内5 min内猫的数量。研究地点的绿化比率和研究地点到市中心距离通过地图(https://map.tianditu.gov.cn/)量化。绿化比率指绿色植被覆盖的面积占研究地点面积的比率;到市中心的距离指研究地点中心到市中心(天安门广场)的直线距离。

1.3 数据分析在29个研究地点共记录到1 326只麻雀的逃逸距离。平均每个地点观测到麻雀45.72只±10.21只。其中, 清华大学记录到的数据量最大(90只),朝阳公园记录到的数据量最小(34只)。计算每个研究地点麻雀逃逸距离(警戒距离、惊飞距离、飞逃距离)的均值进行后续分析,利用每个地点的均值计算总的均值和变异程度。将每个研究地点作为独立的单位是出于如下考虑:公园和高校的绿地是麻雀栖息的重要场所(潘超,郑光美,2003;张淑萍等,2006),而交通主干道等人类建筑会限制麻雀的活动,从而将不同研究地点的麻雀分割为不同的群体。收集的数据也支持这种划分,重复性检验和方差分析均发现研究地点之内的变异显著小于研究地点之间的变异:警戒距离(重复性检验:R=0.17,P < 0.001;方差分析:F28, 1 297=10.34,P < 0.001)、惊飞距离(重复性检验:R=0.18,P < 0.001;方差分析:F28, 1 292=11.28,P < 0.001)、飞逃距离(重复性检验:R=0.07,P < 0.001;方差分析:F28, 980=3.53,P < 0.001)。

计算每个研究地点麻雀群体大小、猫的数量、行人数量的均值。利用线性模型检验影响麻雀逃逸距离的因素。警戒距离、惊飞距离、飞逃距离分别作为模型中的因变量,麻雀群体大小、猫的数量、行人数量、绿化比率、到市中心距离作为模型中的自变量。对于上述5个自变量,在不考虑交互作用的前提下可以有32个潜在的模型(从模型中只含有截距到包括全部的5个自变量)。基于Akaike Information准则(AICc),选用最优模型(AICc值最低)和次优模型(ΔAICc < 2)(表 1),基于模型平均给出最终的模型用以发现影响逃逸距离的因素(Symonds & Moussalli,2011)。

| 因变量 | 模型 | 自变量 | 对数似然比 | AICc | ΔAICc |

| 警戒距离 | 最优模型 | 2,3,5 | -36.81 | 86.22 | 0 |

| 次优模型1 | 2 | -40.44 | 87.84 | 1.61 | |

| 次优模型2 | 2,3,4,5 | -36.14 | 88.10 | 1.88 | |

| 全模型 | 1,2,3,4,5 | -36.08 | 91.49 | 5.27 | |

| 零模型 | — | -44.20 | 92.86 | 6.64 | |

| 惊飞距离 | 最优模型 | 2,3,4,5 | -34.34 | 84.49 | 0 |

| 次优模型1 | 2,4 | -37.84 | 85.35 | 0.86 | |

| 次优模型2 | 2,3,5 | -36.42 | 85.44 | 0.95 | |

| 次优模型3 | 3,4,5 | -36.44 | 85.48 | 0.99 | |

| 次优模型4 | 1,4 | -38.09 | 85.85 | 1.36 | |

| 次优模型5 | 2,4,5 | -36.68 | 85.96 | 1.47 | |

| 次优模型6 | 1,2,4 | -36.86 | 86.33 | 1.84 | |

| 全模型 | 1,2,3,4,5 | -33.89 | 87.12 | 2.62 | |

| 零模型 | — | -43.82 | 92.10 | 7.61 | |

| 飞逃距离 | 最优模型 | 1,3 | -49.49 | 108.64 | 0 |

| 次优模型1 | 3 | -51.74 | 110.45 | 1.80 | |

| 全模型 | 1,2,3,4,5 | -49.10 | 117.53 | 8.88 | |

| 零模型 | — | -56.86 | 118.19 | 9.54 | |

| 注:自变量1~5分别代表猫的数量、到市中心距离、麻雀群体大小、行人数量和绿化比率 Notes: independent variables 1-5 indicate number of cats, distance from city center, flock size of tree sparrows, number of pedestrians, and vegetation cover, respectively | |||||

统计分析利用R 4.0.0(R Development Core Team,2020)完成,其中重复性检验基于“rptR”包实现(Nakagawa & Schielzeth,2010),模型平均基于“MuMIn”包实现(Bartoń,2020)。数据用x ±SD表示。显著性水平设置为α=0.05。

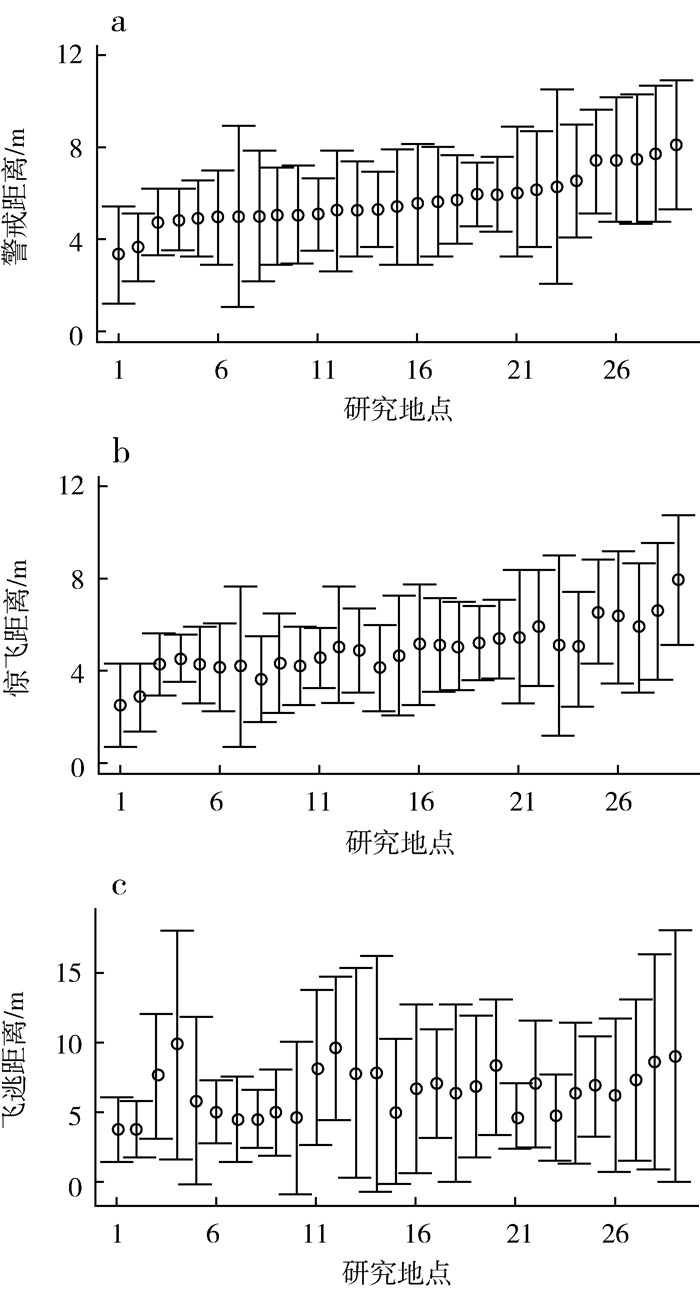

2 结果与分析麻雀的警戒距离为5.67 m±1.13 m,北海公园最小(3.32 m±2.11 m),海淀公园最大(8.08 m± 2.81 m)(图 1:a)。麻雀的惊飞距离为4.92 m±1.12 m,北海公园最小(2.53 m±1.78 m),海淀公园最大(7.91 m±2.80 m)(图 1:b)。麻雀的飞逃距离为6.51 m±1.75 m,北海公园最小(3.77 m±2.32 m),颐和园最大(9.90 m±8.20 m)(图 1:c)。

|

| 图 1 麻雀的警戒距离(a)、惊飞距离(b)和飞逃距离(c) Fig. 1 Escape-related distances of tree sparrows: alert distance (a), flight initiation distance (b), distance fled (c) 横坐标数值从1到29分别对应北海公园、景山公园、中山公园、颐和园、紫竹院公园、对外经济贸易大学、地坛公园、北京理工大学、北京航空航天大学、清华大学、北京第二外国语学院、陶然亭、北京大学、北京科技大学、北京邮电大学、北京林业大学、中国传媒大学、中国农业大学、中国人民大学、玉渊潭公园、香山公园、中央财经大学、奥林匹克森林公园、中国地质大学、天坛公园、北京植物园、朝阳公园、华北电力大学、海淀公园 The values from 1 to 29 on X-axis corresponding to Beihai Park, Jingshan Park, Zhongshan Park, Summer Palace, Zizhuyuan Park, University of International Business and Economics, Ditan Park, Beijing Institute of Technology, Beihang University, Tsinghua University, Beijing International Studies University, Taoranting Park, Peking University, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications, Beijing Forestry University, Communication University of China, China Agricultural University, Renmin University of China, Yuyuantan Park, Fragrant Hills Park, Central University of Finance and Economics, Olympic Forest Park, China University of Geosciences, Tiantan Park, Beijing Botanical Garden, Chaoyang Park, North China Electric Power University, and Haidian Park |

| |

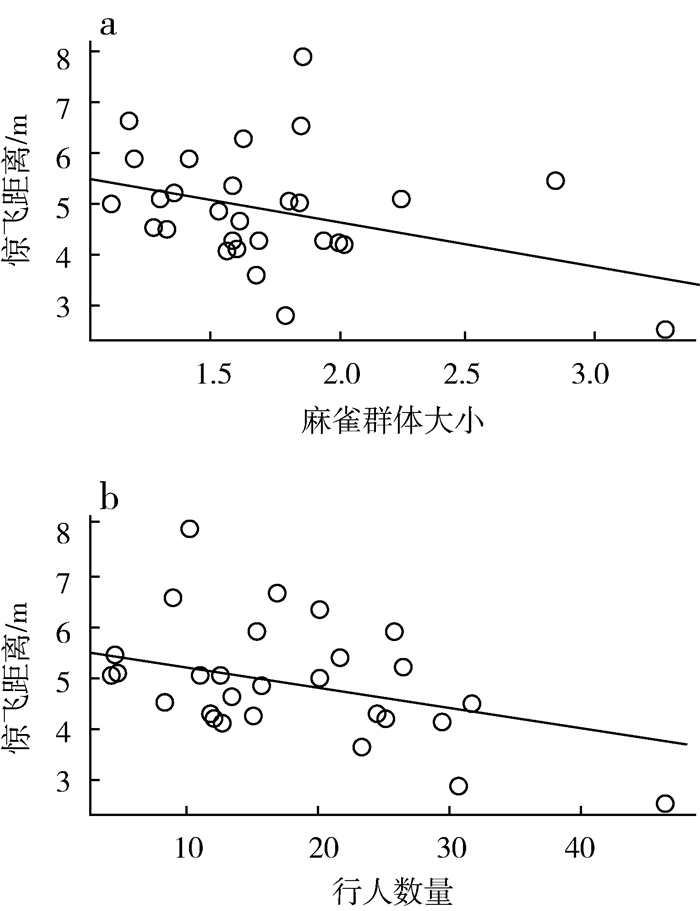

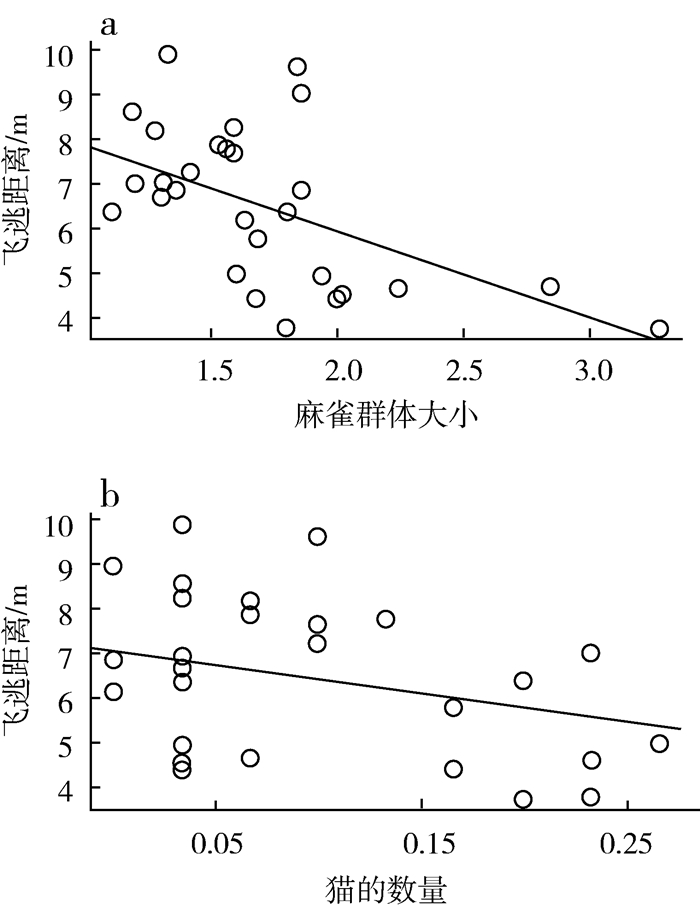

麻雀逃逸距离受到麻雀群体大小、猫的数量、行人数量、绿化比率、到市中心距离的共同影响(表 2)。警戒距离随群体大小的增加而减小(图 2:a),随绿化比率的增加而增加(图 2:b),随到市中心距离的增加而增加(图 2:c);惊飞距离随群体大小的增加而减小(图 3:a),随行人数量的增加而减小(图 3:b);飞逃距离随群体大小的增加而减小(图 4:a),随猫的数量的增加而减小(图 4:b)。

| 因变量 | 自变量 | 回归系数 | 标准误 | Z | P |

| 警戒距离 | 麻雀群体大小 | -0.91 | 0.41 | 2.10 | 0.036 |

| 行人数量 | -0.02 | 0.02 | 1.01 | 0.314 | |

| 绿化比率 | 1.47 | 0.69 | 2.02 | 0.044 | |

| 到市中心距离 | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.39 | 0.017 | |

| 惊飞距离 | 麻雀群体大小 | -0.86 | 0.40 | 2.03 | 0.042 |

| 猫的数量 | -3.72 | 2.36 | 1.50 | 0.133 | |

| 行人数量 | -0.04 | 0.02 | 2.01 | 0.045 | |

| 绿化比率 | 1.40 | 0.70 | 1.91 | 0.057 | |

| 到市中心距离 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 1.86 | 0.063 | |

| 飞逃距离 | 麻雀群体大小 | -1.90 | 0.58 | 3.13 | 0.002 |

| 猫的数量 | -6.70 | 3.20 | 2.00 | 0.046 |

|

| 图 2 影响麻雀警戒距离的因素 Fig. 2 Factors influencing the alert distance of tree sparrows |

| |

|

| 图 3 影响麻雀惊飞距离的因素 Fig. 3 Factors influencing flight initiation distance of tree sparrows |

| |

|

| 图 4 影响麻雀飞逃距离的因素 Fig. 4 Factors influencing the distance fled of tree sparrows |

| |

城市化使野生动物与人类建立了紧密的联系(Sala et al., 2000;Clergeau,2006)。而行为调节是在城市化过程中促进野生动物与人类共存的关键因素(Lowry et al., 2013;Sol et al., 2013)。逃逸行为是鸟类最常采用的反捕食策略(蒋一婷,丁长青,2014;Cooper & Blumstein,2015;方小斌等,2017)。鸟类的逃逸距离受到自然选择的优化,以便在躲避风险和保持能量之间做出权衡(Dowling & Bonier,2018)。本研究通过对北京城区29个公园和高校的1 326只麻雀的研究,量化了麻雀逃逸距离的3个组分:警戒距离、惊飞距离和飞逃距离,发现不同地点麻雀的逃逸距离存在明显的差异。本研究的结果与在天津、郑州、合肥、杭州的研究结果类似(王彦平等,2004;叶淑英等,2013;潘汝南等,2018;鲍明霞等,2019):麻雀的逃逸距离在不同生境存在显著的差异。

在跨物种的比较研究中,发现鸟类的逃逸距离和物种的分布区、觅食生态位等生活史特征有着密切联系(Blumstein,2019;Møller & Xia,2020)。在这些研究中,通常忽视特征(如逃逸距离)在种内的变异,或是默认种内变异远小于种间变异(Stone et al., 2011;Garamszegi,2014)。当种内变异较大的时候,忽略种内变异会影响到跨物种比较研究的功效,或是产生有偏差的结论(Ashton,2004;Ives et al., 2007;Hansen & Bartoszek,2012)。本研究发现,北京城区不同研究地点麻雀的逃逸距离相差可达2~3倍。该变异程度与种间逃逸距离变异程度相当,如,热带鸟类的惊飞距离(15.6 m)约是温带鸟类(7.7 m)的2倍(Møller & Liang,2013)。这说明在跨物种比较研究中,忽略种内逃逸距离的变异可能并不妥当,种内逃逸距离的变异需要在研究中得到重视。

本研究对影响麻雀逃逸距离的因素进行了探讨。麻雀的警戒距离、惊飞距离和飞逃距离均随着群体大小的增加而下降。该结果支持群体大小增加稀释单只个体的风险,从而减小逃逸距离。与本研究结果相反,已有的例证普遍支持群体大小与逃逸距离正相关(Stankowich & Blumstein,2005;Cooper & Blumstein,2015)。已有的研究多是基于个体水平(Stankowich & Blumstein,2005;Cooper & Blumstein,2015),而本研究以每个研究地点为独立的单位,是对群体水平的研究。相同的性状在个体水平和群体水平可能产生截然不同的效果(Rankin,2005;Rankin et al., 2007)。猫是城市鸟类的重要捕食者(Beckerman et al., 2007;Møller,2011)。麻雀的飞逃距离随着猫的数量的增加而减小,可能是因为鸟类更容易观察到较近的位置,选择较近的飞逃位置有助于降低被猫捕食的风险。城市中生活的野生动物对人类干扰警戒性的降低可减少因频繁逃逸而造成的能量消耗(王彦平等,2004;Legagneux & Ducatez,2013;Samia et al., 2015)。麻雀的惊飞距离随着行人数量的增加而减小。这可能是麻雀适应人类干扰的体现(张谦益等, 2019)。麻雀的警戒距离随着生境中的绿化比率增加而增加。研究地点的绿地以开阔的草坪为主。开阔的生境不利于提供有效的庇护场所,导致鸟类需要更长的逃逸距离(Cooper,2003;Tatte et al., 2018)。北京城市化是由中心向四周发展,到市中心距离远表明较短的城市化历程,且距离自然生境更近(艾伟等,2008)。相比栖息于城市的鸟类,自然生境的鸟类有更长的逃逸距离(Møller,2008;Sol et al., 2018)。麻雀的警戒距离随着研究地到市中心距离的增加而增加,可能是栖息地从高度城市化的生境向自然生境过渡的体现。

4 结论通过对1 326只麻雀的研究,发现麻雀的警戒距离为5.67 m±1.13 m、惊飞距离为4.92 m±1.12 m、飞逃距离为6.51 m±1.75 m。不同研究地点麻雀逃逸距离的差异可达2~3倍,与种间逃逸距离的差异程度相当。这暗示种内逃逸距离的变异不能简单地被忽略。逃逸距离反映了动物的风险权衡,受外部环境和动物自身的共同影响。在缺乏庇护场所的地点,麻雀表现出更长的警戒距离;在大的群体中随着个体承受风险的稀释,麻雀会减小逃逸距离。此外,逃逸行为还随潜在危险程度改变,表现为当生境中捕食者猫的数量较多时,麻雀选择较近的飞逃位置。本研究有助于增进了解逃逸距离的种内变异,并可为探讨野生动物在城市生境的适应机制提供基础资料。

致谢: 感谢Møller Anders Pape教授对数据分析的指导与建议。

艾伟, 庄大方, 刘友兆. 2008. 北京市城市用地百年变迁分析[J]. 地球信息科学, 10(4): 489-494. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1560-8999.2008.04.012 |

鲍明霞, 杨森, 杨阳, 等. 2019. 城市常见鸟类对人为干扰的耐受距离研究[J]. 生物学杂志, 36(1): 55-59. |

方小斌, 邹瑀琦, 丁长青. 2017. 鸟类惊飞距离及其影响因素[J]. 动物学杂志, 52(5): 897-910. |

蒋一婷, 丁长青. 2014. 非致命性捕食风险对鸟类的影响[J]. 动物学杂志, 49(4): 613-620. |

潘超, 郑光美. 2003. 北京师范大学内麻雀冬季活动区的研究[J]. 北京师范大学学报(自然科学版), 39(4): 537-540. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0476-0301.2003.04.023 |

潘汝南, 赵树兰, 多立安. 2018. 飞机噪声与人为干扰对麻雀惊飞距离的影响[J]. 天津师范大学学报(自然科学版), 38(5): 42-46, 80. |

阮向东. 1989. 麻雀生态学研究进展[J]. 动物学杂志, 24: 11, 44-48. |

王彦平, 陈水华, 丁平. 2004. 惊飞距离——杭州常见鸟类对人为侵扰的适应性[J]. 动物学研究, 25(3): 214-220. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0254-5853.2004.03.005 |

胥帅帅, 邓竹青, 陈功, 等. 2018. 麻雀两性羽色的比较[J]. 动物学杂志, 53(5): 693-700. |

叶淑英, 王振龙, 路纪琪. 2013. 人为干扰对城市园林麻雀惊飞距离的影响[J]. 郑州大学学报(理学版), 45(4): 96-101. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-6841.2013.04.020 |

张谦益, 钟浩, 何飘雨, 等. 2019. 麻雀幼鸟和成鸟逃逸距离的比较[J]. 动物学杂志, 54(5): 627-635. |

张淑萍, 郑光美, 徐基良. 2006. 城市化对城市麻雀栖息地利用的影响: 以北京市为例[J]. 生物多样性, 14(5): 372-381. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-0094.2006.05.002 |

Ashton KG. 2004. Comparing phylogenetic signal in intraspecific and interspecific body size datasets[J]. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 17(5): 1157-1161. DOI:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2004.00764.x |

Bartoń K. 2020. MuMIn: multi-model inference. R package version 1.43.17[EB/OL]. (2020-4-15)[2020-12-6]. https://mirrors.tuna.tsinghua.edu.cn/CRAN/.

|

Beckerman AP, Boots M, Gaston KJ. 2007. Urban bird declines and the fear of cats[J]. Animal Conservation, 10(3): 320-325. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00115.x |

Blumstein DT, Samia DSM, Cooper WE. 2016. Escape behavior: dynamic decisions and a growing consensus[J]. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 12: 24-29. DOI:10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.08.006 |

Blumstein DT. 2019. What chasing birds can teach us about predation risk effects: past insights and future directions[J]. Journal of Ornithology, 160(2): 587-592. DOI:10.1007/s10336-019-01634-1 |

Cardoso GC. 2014. Nesting and acoustic ecology, but not phylogeny, influence passerine urban tolerance[J]. Global Change Biology, 20(3): 803-810. DOI:10.1111/gcb.12410 |

Clergeau P. 2006. Avifauna homogenisation by urbanisation: analysis at different European latitudes[J]. Biology Conservation, 127(3): 336-344. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.06.035 |

Cooper WE, Blumstein DT. 2015. Escaping from predators: an integrative view of escape decisions[M]. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

Cooper WE, Frederick WG. 2007. Optimal flight initiation distance[J]. Journal of Theoretical Biology, 244(1): 59-67. DOI:10.1016/j.jtbi.2006.07.011 |

Cooper WE. 2003. Risk factors affecting escape behavior by the desert iguana, Dipsosaurus dorsalis: speed and directness of predator approach, degree of cover, direction of turning by a predator, and temperature[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 81(6): 979-984. DOI:10.1139/z03-079 |

Dowling L, Bonier F. 2018. Should I stay, or should I go: modeling optimal flight initiation distance in nesting birds[J/OL]. PLoS ONE, 13(11): e0208210[2020-06-30]. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208210.

|

Garamszegi LZ. 2014. Uncertainties due to within-species variation in comparative studies: measurement errors and statistical weights[M]//Garamszegi LZ. Modern phylogenetic comparative methods and their application in evolutionary biology. New York: Springer.

|

Hansen TF, Bartoszek K. 2012. Interpreting the evolutionary regression: the interplay between observational and biological errors in phylogenetic comparative studies[J]. Systematic Biology, 61(3): 413-425. DOI:10.1093/sysbio/syr122 |

Huang D, Su Z, Zhang R, et al. 2010. Degree of urbanization influences the persistence of Dorytomus weevils (Coleoptera: Curculionoidae) in Beijing, China[J]. Landscape and Urban Planning, 96(3): 163-171. DOI:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2010.03.004 |

Ives AR, Midford PE, Garland T. 2007. Within-species variation and measurement error in phylogenetic comparative methods[J]. Systematic Biology, 56(2): 252-270. DOI:10.1080/10635150701313830 |

Legagneux P, Ducatez S. 2013. European birds adjust their flight initiation distance to road speed limits[J/OL]. Biology Letters, 9(5): 20130417[2020-06-30]. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2013.0417.

|

Lowry H, Lill L, Wong BBM. 2013. Behavioural responses of wildlife to urban environments[J]. Biological Reviews, 88(3): 537-549. DOI:10.1111/brv.12012 |

Luck GW. 2007. A review of the relationships between human population density and biodiversity[J]. Biological Reviews, 82(4): 607-645. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00028.x |

Møller AP, Liang W. 2013. Tropical birds take small risks[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 24(1): 267-272. DOI:10.1093/beheco/ars163 |

Møller AP, Nielsen JT, Garamszegi LZ. 2008. Risk taking by singing males[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 19(1): 41-53. DOI:10.1093/beheco/arm098 |

Møller AP, Samia DSM, Weston MA, et al. 2016. Flight initiation distances in relation to sexual dichromatism and body size in birds from three continents[J]. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 117(4): 823-831. DOI:10.1111/bij.12706 |

Møller AP, Xia CW. 2020. The ecological significance of birds feeding from the hand of humans[J/OL]. Scientific Reports, 10: 9773[2020-06-30]. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-66165-9.

|

Møller AP. 2008. Flight distance of urban birds, predation, and selection for urban life[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 63(1): 63-75. DOI:10.1007/s00265-008-0636-y |

Møller AP. 2011. Song post height in relation to predator diversity and urbanization[J]. Ethology, 117(6): 529-538. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2011.01899.x |

Nakagawa S, Schielzeth H. 2010. Repeatability for Gaussian and non-Gaussian data: a practical guide for biologists[J]. Biological Reviews, 85(4): 935-956. |

Parris KM, Schneider A. 2009. Impacts of traffic noise and traffic volume on birds of roadside habitats[J/OL]. Ecology and Society, 14(1): 29[2020-06-30]. https://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol14/iss1/art29/.

|

Rankin DJ, Bargum K, Kokko H. 2007. The tragedy of the commons in evolutionary biology[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 22(12): 643-651. |

Rankin DJ. 2005. Can adaptation lead to extinction?[J]. Oikos, 111(3): 616-619. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2005.14541.x |

Sala OE, Chapin FS, Armesto JJ, et al. 2000. Global biodiversity scenarios for the year 2100[J]. Science, 287(5459): 1770-1774. DOI:10.1126/science.287.5459.1770 |

Samia DSM, Nakagawa S, Nomura F, et al. 2015. Increased tolerance to humans among disturbed wildlife[J/OL]. Nature Communications, 6: 8877[2020-06-30]. https://nature.com/articles/ncomms9877/.

|

Schlesinger MD, Manley PN, Holyoak M. 2008. Distinguishing stressors acting on land bird communities in an urbanizing environment[J]. Ecology, 89(8): 2302-2314. DOI:10.1890/07-0256.1 |

Slabbekoorn H, Ripmeester EAP. 2008. Birdsong and anthropogenic noise: implications and applications for conservation[J]. Molecular Ecology, 17(1): 72-83. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03487.x |

Sol D, Lapiedra O, González-Lagos C. 2013. Behavioural adjustments for a life in the city[J]. Animal Behaviour, 85(5): 1101-1112. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.01.023 |

Sol D, Maspons J, Gonzalez-Voyer A, et al. 2018. Risk-taking behavior, urbanization and the pace of life in birds[J/OL]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 72(3): 59[2020-06-30]. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00265-018-2463-0.

|

Stankowich T, Blumstein DT. 2005. Fear in animals: a meta-analysis and review of risk assessment[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272(1581): 2627-2634. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2005.3251 |

Stone GN, Nee S, Felsenstein J. 2011. Controlling for non-independence in comparative analysis of patterns across populations within species[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 366(1569): 1410-1424. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2010.0311 |

Symonds MRE, Moussalli A. 2011. A brief guide to model selection, multimodel inference and model averaging in behavioural ecology using Akaike's information criterion[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 65(1): 13-21. DOI:10.1007/s00265-010-1037-6 |

Tatte K, Møller AP, Mand R. 2018. Towards an integrated view of escape decisions in birds: relation between flight initiation distance and distance fled[J]. Animal Behaviour, 136(1): 75-86. |

Ydenberg RC, Dill LM. 1986. The economics of fleeing from predators[J]. Advances in the Study of Behavior, 16: 229-249. |

2021, Vol. 40

2021, Vol. 40