扩展功能

文章信息

- 许双, 戴强, 张丕珠, 郑渝池

- XU Shuang, DAI Qiang, ZHANG Pizhu, ZHENG Yuchi

- 两栖类皮肤石蜡切片样本量探讨——以峨眉髭蟾毛细血管丰富度为例

- Sample Sizes for Paraffin Section of Amphibian Skin-a Case Study of Capillary Density in Leptobrachium boringii

- 四川动物, 2020, 39(3): 274-280

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2020, 39(3): 274-280

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20200024

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2020-01-16

- 接受日期: 2020-03-23

2. 中国科学院大学, 北京 100049

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

两栖动物皮肤的功能包括离子及水交换(Bentley & Yorio,1979;Marrero & Hillyard,1985;Sullivan et al., 2000)、感觉(Kitson & Roberts,1983;Mearow & Diamond,1988)、机械与化学防御(Fox,1986;Evans & Brodie,1994;Woodhams et al., 2007;Jeckel et al., 2015)和呼吸(Duellman & Trueb,1994;Nussbaum & Wilkinson,1995;Bickford et al., 2008;Robischon,2017)。对皮肤各功能对应结构特征的量化常借助石蜡切片技术,涉及如分裂相表皮细胞比例(耿欣莲,1959)、皮肤各层厚度(Greven et al., 1995;Barrionuevo,2017;Yang et al., 2019)、腺体数量和大小(de Almeida et al., 2007;Gonçalves & de Brito-Gitirana,2008;Yang et al., 2019)等。特征值的准确获得受样本设计影响。目前在石蜡切片技术领域,即使针对相同特征,已发表工作所采用的设计(包括切片数、测量数等)也少见统一(Norris et al., 1989;刘满樱等,2007;李洋等,2009;Prates et al., 2012;Brunetti et al., 2016;Barrionuevo,2017;Ponssa et al., 2017;Wanninger et al., 2018)。例如皮肤各层厚度的测量,曹燕等(2011)对齿突蟾属Scutiger 4个物种背腹面等距测量5次,而Chammas等(2015)对疣蟾Rhinella granulosa背腹面测量30次,Ponssa等(2017)对细趾蟾属Leptodactylus物种背部不同部位测量5次,VanBuren等(2019)对白唇树蛙Litoria infrafrenata背腹及后肢腹面随机测量10次。

不同结构特征的量化,缘其自身特点,对样本设计的要求理当不同。实际工作中,同一批次石蜡切片样品往往为不同特征提供数据。通过直接测量即可获得数据的指标,如厚度可能需要较小的样本量。而另外一些无法直接测量的特征则可能需要更大工作量的取样,进而影响制备切片样品的策略和工作量。因此,对后者样本设计的探讨有利于实践工作。

皮肤气体交换主要发生于表皮下毛细血管,其密度为衡量呼吸能力的一项重要参数(Krogh,1904;Feder & Burggren,1985;Malvin, 1988, 1993)。通过向两栖动物活体心脏注射墨水,可染色毛细血管并测量其单位面积内的长度(Czopek,1965;de Saint-Aubain,1982)。但基于动物伦理的考量,该方法近年来已罕有使用,现常用石蜡切片计数评估皮肤毛细血管丰富度。基于毛细血管计数和切面长度,单条切片仅可提供一个丰富度值。为获得有代表性的结果,需要相当的样本量。在长时间完全没入水中的情况下,一些蛙类有战斗和鸣叫等依赖于高效率皮肤呼吸的行为,但其相应皮肤毛细血管特征尚待研究。这些蛙类中生活史和行为学研究开展较多的物种之一为峨眉髭蟾Leptobrachium boringii(Zheng et al., 2011;Hudson & Fu,2013)。本研究以峨眉髭蟾10个部位表皮下毛细血管丰富度为例,通过对样本进行重抽样,探讨取样与结果稳定性的关系,以期为两栖类皮肤切片的样品制备策略提供参考。

1 材料与方法峨眉髭蟾隶属角蟾科Megophryidae,主要分布于四川盆地周边山地,每年2—4月于溪流中繁殖,其余时间陆栖。2只峨眉髭蟾标本于2019年5、6月采自四川省峨眉山,均为非繁殖季节雄性成体,编号为IOZCAS09432(吻肛距=80.6 mm,大个体)、IOZCAS09433(吻肛距=72.2 mm,小个体)。该物种非繁殖季节时活动隐秘,陆栖个体多年来少有获取,对其陆栖个体皮肤毛细血管丰富度的报道有利于国内外同行据此进行对比分析。气体交换是蛙类皮肤的重要功能,体型较大的个体因其体表面积/体质量比较小,毛细血管丰富度较高。2只个体体型大小不同,若符合该预期则支持实测结果的可靠性。麻醉采用低于5%乙醇以减小刺激,固定液为8%甲醛,固定后流水置换甲醛24 h再转70%乙醇长期保存。切片前,每只蛙取头背部、躯干背部、前肢背侧、后肢背侧、体侧、下颌、胸部、下腹、前肢腹侧、后肢腹侧10个身体右侧部位皮肤,均为5 mm×6 mm长方形。对皮肤组织进行常规石蜡包埋切片,切片厚度6 μm。每块皮肤尽量获得约15张载玻片的连续切片,每张载玻片上为3列、每列15条切片。苏木精-伊红染色(Preece,1965),树胶封片。

使用徕卡DM2500显微镜加装DFC495相机观察、拍照。每块皮肤测量5张载玻片、每隔2张测量1张;同一载玻片测量6条组织、每隔7条测量1条;同一条组织获取1张显微图像测量、大小为1 255 μm×942 μm。图像内,计数表皮下毛细血管数量,利用ImageJ version 1.52a(Schneider et al., 2012)测量表皮长度,得出单位长度表皮下毛细血管数为1个丰富度样本值。由此得到跨度约3.5 mm的30个样本值,结果以x表示。

编写R脚本对30个样本值无放回抽样,模拟1载玻片×1图像、1载玻片×2图像、……、1载玻片×6图像、2载玻片×1图像、……、5载玻片×5图像共29种样本设计,每种设计1 000次重复。不同设计的样本大小共16种情况,包括1、2、3、4、5、6、8、9、10、12、15、16、18、20、24、25。不同载玻片被抽取的皮肤切片/图像位置相同,以契合常见的等距取样策略(曹燕等,2011;Brunetti et al., 2012;Prates et al., 2012)。1 000个模拟结果的均值几等于真实结果。以真实结果的5%为评判阈值,即样本均值×0.05,若其大于1 000个模拟结果的标准差,则大多数模拟结果和真实结果的相似性高于95%、该模拟设计可靠。以此相似性标准,统计各部位获得接近真实结果所需样本量,记录满足该标准的3个最小样本量的中位数。为比较相同样本量、不同工作量的设计,对“1载玻片×5图像、5载玻片×1图像”和“2载玻片×5图像、5载玻片×2图像”这2对设计的模拟结果标准差进行配对t检验。对毛细血管丰富度和可靠设计数量进行Pearson相关检验,以探索前者对所需样本量的影响。各检验在SPSS 11.0中进行,数据处理前用Kolmogorov-Smirnov检验确认用于配对t检验的变量的差值和用于Pearson检验的变量不显著偏离正态分布(P值均大于0.05)。

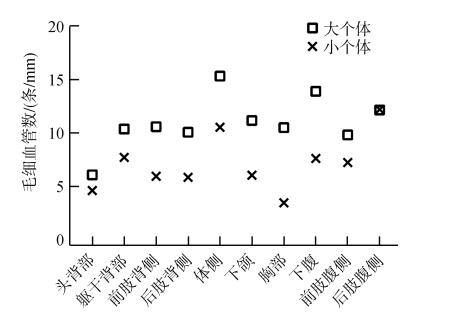

2 结果2只个体表皮下毛细血管丰富度分布模式基本一致。与其理论上较低的体表面积/体质量比值相符,大个体各部位毛细血管丰富度多高于小个体(图 1)。两者在体侧和后肢腹侧都有较高密度的毛细血管,为10.5~15.3条/mm;而头背部是毛细血管密度均较低的部位,分别为4.6条/mm和6.1条/mm。

|

| 图 1 2只雄性峨眉髭蟾身体右侧10个部位表皮下毛细血管丰富度 Fig. 1 Densities of capillaries beneath the epidermis in 10 parts on the right side of 2 male Leptobrachium boringii |

| |

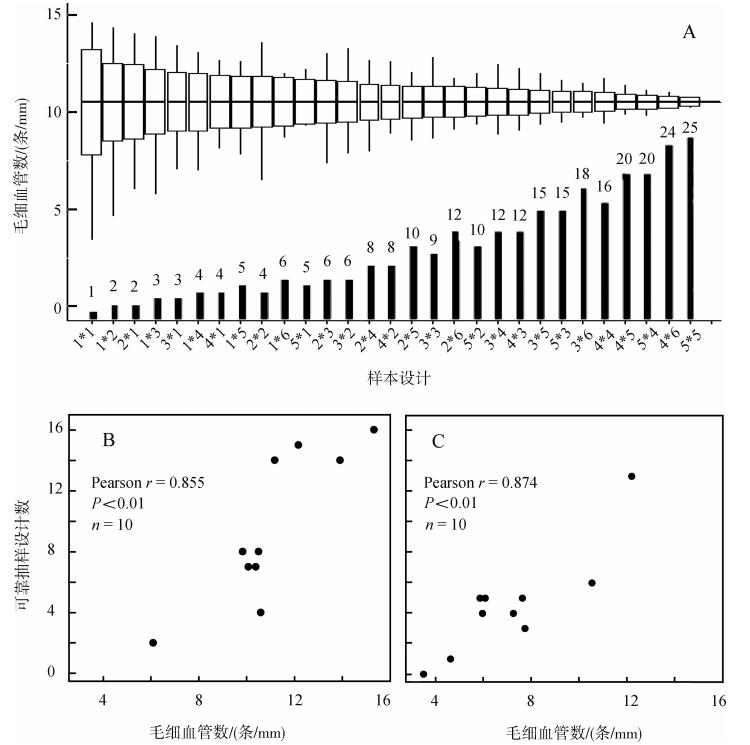

和预期相符,模拟结果随着样本量的增加趋近实测值(图 2:A)。各部位模拟结果有差异(表 1):体侧、下颌、下腹、后肢腹侧获得接近真实结果所需最小样本量约为8,密度较低的头背部则需20或25,密度最低的小个体胸部无法获得接近真实值的模拟结果。大个体所需样本量更小、可靠样本设计共95个,小个体为46个;除前肢背侧相同外,大个体各部位可靠样本设计均多于小个体。Pearson相关检验表明,2只个体各部位毛细血管丰富度和可靠设计数量均呈显著正相关(图 2:B,C),大、小个体相关系数分别为0.855和0.874(P值均小于0.01,n=10)。配对t检验显示,当样本量固定为5或10时,不同工作量的抽样设计对结果影响不明显,模拟结果标准差之间的差异无统计学意义(P值均大于0.1,n=10)。

|

| 图 2 模拟结果示例和毛细血管丰富度对所需样本量的影响 Fig. 2 An example of the simulation results and the relationship between capillary densities and sample sizes required A.小个体模拟结果,横轴显示模拟参数,如2*5代表观察2张载玻片、每载玻片5个图像,数值为样本量、与黑色柱形高度一致,箱形为模拟结果(x ± s和范围),竖线代表模拟结果范围;B.大个体毛细血管丰富度与可靠设计数的关系;C.小个体毛细血管丰富度与可靠设计数的关系 A. Simulation results for the density of capillaries beneath the epidermis in the flank of the small male individual, horizontal coordinates are sampling designs, e.g., 2*5 means sampling 2 slides and 5 images per slide, numbers refer to sample sizes which are proportional to the heights of black bars; box plots show x ± s and range; B. the correlation between capillary densities and numbers of successful sampling designs observed in the large male individual; C. the correlation between capillary densities and numbers of successful sampling designs observed in the small male individual |

| |

| 部位 | 可靠模拟设计数 | 3个最小样本量的中位数 | |||

| 大个体 | 小个体 | 大个体 | 小个体 | ||

| 头背部 | 2 | 1 | 20*、25* | 25* | |

| 躯干背部 | 7 | 3 | 15 | 24 | |

| 前肢背侧 | 4 | 4 | 20 | 20 | |

| 后肢背侧 | 7 | 5 | 16 | 20 | |

| 体侧 | 16 | 6 | 8 | 18 | |

| 下颌 | 14 | 5 | 8 | 20 | |

| 胸部 | 8 | — | 15 | — | |

| 下腹 | 14 | 5 | 8 | 18 | |

| 前肢腹侧 | 8 | 4 | 15 | 15 | |

| 后肢腹侧 | 15 | 13 | 8 | 10 | |

| 注:*可靠模拟设计数小于3时,直接列出样本量 Note:* When there are less than 3 successfully simulated sampling designs,the sample size of each design is listed |

|||||

本研究系统中,对一些部位如头背部、前肢背侧表皮下毛细血管丰富度的量化需要较多的切片。对比大、小个体,各部位表皮下毛细血管相对丰富度分布基本一致,有较小体表面积/体质量比的大个体毛细血管丰富度更高。两者体侧和后肢腹侧较高的毛细血管密度与在蛙类中已观察到的模式相同(Czopek,1965;Toledo & Jared,1993)。无尾两栖类后肢腹侧是皮肤水、气交换的关键部位,毛细血管密度一般较高(Roth,1973;Bentley & Yorio,1979)。这些一致性提示本工作的实测结果可靠。基于实测数据的模拟显示,小个体雄性多数部位需要接近20条组织或更高的样本量,大个体多数部位需要接近15条或更高的样本量。对比相同样本量、不同工作量的取样设计,基于较大工作量即更多制片的取样未得到显著理想的结果。但2对设计的样本量均较小,分别为5和10,不足以支持较少制片的策略,有待于在更合适的研究系统中探讨。一套皮肤石蜡切片可用于不同特征的量化,实际工作中也常如此,制片量不能仅针对需少量样本即可准确量化的特征。常规石蜡切片实验周期较长,但更多的展片、染色、封片并不会大幅增加工作量。相反,如果后期发现样本量不够、追加取样则会成倍耗费时间。另外,以毛细血管密度为例,一些特征在两栖动物皮肤不同部位的分布很不均一(Moalli et al., 1980),追加取样可能难以对应部位、无法补救。因此,建议在两栖类皮肤石蜡切片工作中对全部有效切片进行制片,以满足不同特征对样本量的要求。

对比不同个体相同部位以及同一个体不同部位,表皮下毛细血管丰富度与所需样本量呈负相关。这显示来自高血管丰富度部位的测量值方差更小,这些部位的血管分布可能更均匀。这样的规律是否在其他两栖动物中存在、在什么样的毛细血管丰富度范围内存在,仍需考查。如有其普遍性,则对实际工作有指导意义。如前所述,同一物种的较小个体一般有更高的皮肤面积/体质量比,故可能有较低的毛细血管密度。两栖动物皮肤毛细血管丰富度分布有一定规律可循,部分物种的该特征已有量化(Czopek,1965;de Saint-Aubain,1982;Malvin,1988;Toledo & Jared,1993)。某些生活史特征如陆栖、水栖与该特征关联(耿欣莲,1959;唐以杰等,1999;Barej et al., 2010)。这些已有信息可否用于抽样策略的制定,有待在其他两栖动物类群中进行与本工作类似的相关性分析。需要指出的是,本工作以模拟结果的标准差是否小于实测结果值的5%为判断依据,该阈值在低丰富度部位显然更小,但这样的设定更符合以相似性评判结果稳定性的实践标准。

致谢: 衷心感谢中国科学院成都生物研究所曾一唯师姐、周星梅老师、曾晓茂老师的帮助与建议。

曹燕, 谢锋, 江建平. 2011. 齿突蟾属四个物种皮肤的组织学观察[J]. 四川动物, 30(2): 214-219. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-7083.2011.02.015 |

耿欣莲. 1959. 大蟾蜍(Bufo bufo gargarizans Cantor)皮肤在不同季节中的组织学观察[J]. 动物学报, 11(3): 313-325. |

李洋, 金磊, 李昌春, 等. 2009. 黑斑蛙、虎纹蛙和牛蛙皮肤的比较组织学[J]. 安徽师范大学学报(自然科学版), 32(5): 466-470. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-2443.2009.05.014 |

刘满樱, 肖向红, 徐佳佳, 等. 2007. 东北林蛙皮肤及其腺体组织形态学观察[J]. 野生动物, 28(4): 6-9. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-0127.2007.04.002 |

唐以杰, 曾小龙, 方昆阳. 1999. 中国大鲵皮肤的组织学观察[J]. 广东科技, (7): 26-27. |

Ba rej MF, Boehme W, Perry SF, et al. 2010. The hairy frog, a curly fighter? A novel hypothesis on the function of hairs and claw-like terminal phalanges, including their biological and systematic significance (Anura: Arthroleptidae: Trichobatrachus)[J]. Revue Suisse de Zoologie, 117(2): 243-263. |

Barrionuevo JS. 2017. Skin structure variation in water frogs of the genus Telmatobius (Anura: Telmatobiidae)[J]. Salamandra, 53(2): 183-192. |

Bentley AJ, Yorio T. 1979. Do frogs drinks?[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 79(1): 41-46. |

Bickford D, Iskandar D, Barlian A. 2008. A lungless frog discovered on Borneo[J]. Current Biology, 18(9): 374-375. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2008.03.010 |

Brunetti AE, Hermida GN, Faivovich J. 2012. New insights into sexually dimorphic skin glands of anurans: the structure and ultrastructure of the mental and lateral glands in Hypsiboas punctatus (Amphibia: Anura: Hylidae)[J]. Journal of Morphology, 273(11): 1257-1271. DOI:10.1002/jmor.20056 |

Brunetti AE, Hermida GN, Iurman MG, et al. 2016. Odorous secretions in anurans: morphological and functional assessment of serous glands as a source of volatile compounds in the skin of the treefrog Hypsiboas pulchellus (Amphibia: Anura: Hylidae)[J]. Journal of Anatomy, 228(3): 430-442. DOI:10.1111/joa.12413 |

Chammas SM, Carneiro SM, Ferro RS, et al. 2015. Development of integument and cutaneous glands in larval, juvenile and adult toads (Rhinella granulosa): a morphological and morphometric study[J]. Acta Zoologica, 96(4): 460-477. DOI:10.1111/azo.12091 |

Czopek J. 1965. Quantitative studies on the morphology of respiratory surfaces in amphibians[J]. Acta Anatomica, 62(2): 296. DOI:10.1159/000142756 |

de Almeida PG, Felsemburgh FA, Azevedo RA, et al. 2007. Morphological re-evaluation of the parotoid glands of Bufo ictericus (Amphibia, Anura, Bufonidae)[J]. Contributions to Zoology, 76(3): 145-152. DOI:10.1163/18759866-07603001 |

de Saint-Aubain ML. 1982. The morphology of amphibian skin vascularization before and after metamorphosis[J]. Zoomorphology, 100(1): 55-63. DOI:10.1007/BF00312199 |

Duellman WE, Trueb L. 1994. Biology of amphibians[M]. London: Johns Hopkins.

|

Evans CM, Brodie ED. 1994. Adhesive strength of amphibian skin secretions[J]. Journal of Herpetology, 28(4): 499-502. DOI:10.2307/1564965 |

Feder ME, Burggren WW. 1985. Skin breathing in vertebrates[J]. Scientific American, 253(5): 126-143. DOI:10.1038/scientificamerican1185-126 |

Fox H. 1986. Biology of the integument[M]. Berlin: Springer.

|

Gonçalves VF, de Brito-Gitirana L. 2008. Structure of the sexually dimorphic gland of Cycloramphus fuliginosus (Amphibia, Anura, Cycloramphidae)[J]. Micron, 39(1): 32-39. DOI:10.1016/j.micron.2007.08.005 |

Greven H, Zanger K, Schwinger G. 1995. Mechanical properties of the skin of Xenopus laevis (Anura, Amphibia)[J]. Journal of Morphology, 224(1): 15-22. DOI:10.1002/jmor.1052240103 |

Hudson CM, Fu J. 2013. Male-biased sexual size dimorphism, resource defense polygyny, and multiple paternity in the Emei moustache toad (Leptobrachium boringii) [ J/OL].PLoS ONE, 8(6): e67502. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067502.

|

Jeckel AM, Saporito RA, Grant T. 2015. The relationship between poison frog chemical defenses and age, body size, and sex [ J/OL].Frontiers in Zoology, 12(1): 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12983-015-0120-2.

|

Kitson DL, Roberts A. 1983. Competition during innervation of embryonic amphibian head skin[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences, 218(1210): 49-59. DOI:10.1098/rspb.1983.0025 |

Krogh A. 1904. On the cutaneous and pulmonary respiration of the frog: a contribution to the theory of the gas exchange between the blood and the atmosphere[J]. Skandinavisches Archiv für Physiologie, 15(1): 328-419. DOI:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1904.tb00010.x |

Malvin G. 1993. Microcirculatory effects of hypoxic and hypercapnic vasoconstriction in frog skin[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 264(2): 435-439. DOI:10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.2.R435 |

Malvin GM. 1988. Microvascular regulation of cutaneous gas exchange in amphibians[J]. American Zoologist, 28(3): 999-1007. DOI:10.1093/icb/28.3.999 |

Marrero MB, Hillyard SD. 1985. Differences in c-AMP levels in epithelial cells from pelvic and pectoral regions of the toad skin[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C: Comparative Pharmacology, 82(1): 69-73. DOI:10.1016/0742-8413(85)90211-7 |

Mearow KM, Diamond J. 1988. Merkel cells and the mechanosensitivity of normal and regenerating nerves in Xenopus skin[J]. Neuroscience, 26(2): 695-708. DOI:10.1016/0306-4522(88)90175-3 |

Moalli R, Meyers RS, Jackson DC, et al. 1980. Skin circulation of the frog, Rana catesbeiana: distribution and dynamics[J]. Respiration Physiology, 40(2): 137-148. DOI:10.1016/0034-5687(80)90088-2 |

Norris DO, Austin HB, Huazi AS. 1989. Induction of cloacal and dermal skin glands of tiger salamander larvae, (Ambystoma tigrinum): effects of testosterone and prolactin[J]. General and Comparative Endocrinology, 73(2): 194-204. DOI:10.1016/0016-6480(89)90092-0 |

Nussbaum RA, Wilkinson M. 1995. A new genus of lungless tetrapod: a radically divergent caecilian (Amphibia: Gymnophiona)[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B: Biological Sciences, 261(1362): 331-335. DOI:10.1098/rspb.1995.0155 |

Ponssa ML, Barrionuevo JS, Pucci AF, et al. 2017. Morphometric variations in the skin layers of frogs: an exploration into their relation with ecological parameters in Leptodactylus (Anura, Leptodactylidae), with an emphasis on the Eberth-Kastschenko layer[J]. The Anatomical Record, 300(10): 1895-1909. DOI:10.1002/ar.23640 |

Prates I, Antoniazzi MM, Sciani JM, et al. 2012. Skin glands, poison and mimicry in dendrobatid and leptodactylid amphibians[J]. Journal of Morphology, 273(3): 279-290. DOI:10.1002/jmor.11021 |

Preece A. 1965. A manual for histologic technicians, 2nd edition[M]. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

|

Robischon M. 2017. Surface-area-to-volume ratios, fluid dynamics & gas diffusion: four frogs & their oxygen flux[J]. The American Biology Teacher, 79(1): 64-67. DOI:10.1525/abt.2017.79.1.64 |

Roth JJ. 1973. Vascular supply to the ventral pelvic region of anurans as related to water balance[J]. Journal of Morphology, 140(4): 443-460. DOI:10.1002/jmor.1051400405 |

Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. 2012. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis[J]. Nature Methods, 9(7): 671-675. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.2089 |

Sullivan PA, vonSeckendorff HK, Hillyard SD. 2000. Effects of anion substitution on hydration behavior and water uptake of the red-spotted toad, Bufo punctatus: is there an anion paradox in amphibian skin?[J]. Chemical Senses, 25(2): 167-172. DOI:10.1093/chemse/25.2.167 |

Toledo RC, Jared C. 1993. Cutaneous adaptations to water balance in amphibians[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Physiology, 105(4): 593-608. DOI:10.1016/0300-9629(93)90259-7 |

VanBuren CS, Norman DB, Fröbisch NB. 2019. Examining the relationship between sexual dimorphism in skin anatomy and body size in the white-lipped treefrog, Litoria infrafrenata (Anura: Hylidae)[J]. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 186(2): 491-500. DOI:10.1093/zoolinnean/zly070 |

Wanninger M, Schwaha T, Heiss E. 2018. Form and function of the skin glands in the Himalayan newt Tylototriton verrucosus [J/OL].Zoological Letters, 4(1): 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40851-018-0095-x.

|

Woodhams DC, Ardipradja K, Alford RA, et al. 2007. Resistance to chytridiomycosis varies among amphibian species and is correlated with skin peptide defenses[J]. Animal Conservation, 10(4): 409-417. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2007.00130.x |

Yang C, Fu T, Lan X, et al. 2019. Comparative skin histology of frogs reveals high-elevation adaptation of the Tibetan Nanorana parkeri[J]. Asian Herpetological Research, 10(2): 79-85. |

Zheng Y, Rao D, Murphy RW, et al. 2011. Reproductive behavior and underwater calls in the Emei mustache toad, Leptobrachium boringii[J]. Asian Herpetological Research, 2(4): 199-215. |

2020, Vol. 39

2020, Vol. 39