扩展功能

文章信息

- 张凯, 张萌萌, 徐雨

- ZHANG Kai, ZHANG Mengmeng, XU Yu

- 家燕种群变化趋势研究进展

- Research Progress on the Population Trends of Hirundo rustica

- 四川动物, 2019, 38(5): 587-593

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2019, 38(5): 587-593

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20190062

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2019-02-17

- 接受日期: 2019-07-08

家燕Hirundo rustica几乎遍布全球,主要为迁徙鸟,欧洲种群越冬于非洲撒哈拉以南地区、北美洲种群越冬于中南美洲、东亚种群越冬于南亚至澳洲北部(BirdLife International,2016)。该物种偏好田野、河滩等开阔地,主食昆虫,主要依赖人类建筑物营巢,是人类最熟悉的鸟类之一,具有丰富的文化内涵(赵正阶,2001;Turner & Christie,2012),也是备受关注的研究对象(Brown & Brown,2013;Scordato & Safran,2014)。作为人类的伴生物种(Smith et al., 2018),家燕受人类活动的直接影响,因此是研究“人类世”全球环境变化对动物影响的理想模型之一。

家燕等农田鸟类和食虫鸟类在20世纪70年代和80年代经历了广泛的种群衰减(Siriwardena et al., 1998;潘德根,2003;Imlay et al., 2018),引发了普遍的担忧。虽然家燕在全球范围及主要分布地区并未列为受威胁物种(环境保护部,中国科学院,2015;BirdLife International,2016;US Fish & Wildlife Service,2018),但是其种群下降趋势及威胁因子值得进一步关注(BirdLife International,2016)。

中国是家燕亚洲种群的主要繁殖地,鸟类学者在多地开展了其繁殖生态学的基础研究(周昌乔,李翔云,1959;赵正阶,1982;田丽等,2006;张波,2006;Pagani-Núñez et al., 2016),发现局部地区的家燕种群数量在下降(韩云池等,1992;潘德根,2003),然而区域或者更大空间尺度上家燕种群趋势一直未知。

本研究综述全球范围内家燕的种群动态,并分析影响家燕种群动态的因素,促进对以家燕为代表的食虫鸟类、农田鸟类和迁徙鸟类的研究和保护。与此同时,本研究结合国内外相关研究,为中国家燕监测计划提供一些建议,并号召通过家燕的研究与监测推进中国生物多样性监测(斯幸峰,丁平,2011)和公众科学(张健等,2014)的发展。

1 种群监测项目欧洲和北美洲对家燕种群监测范围较广、历史较长。泛欧洲常见鸟类监测计划(PECBMS,始于1980年)(EBCC/BirdLife/RSPB/CSO,2018)和北美繁殖鸟类调查(BBS,始于1966年)(Sauer et al., 2017b)涵盖了家燕在欧洲和美洲的繁殖地,为家燕等鸟类提供了长期的监测数据。其中,欧洲个别国家的鸟类监测历史更久,如英国常见鸟类调查(CBC)可回溯至1964年(Marchant,1983)。

亚洲尚无大范围的鸟类监测计划,个别地区针对家燕开展了监测,如日本石川县家燕调查(始于1972年)(Ishikawa Prefecture Health Citizens Campaign Promition Headquarters,2011)、中国香港家燕巢调查(始于2003年)(香港观鸟会,2009)。此外,澳大利亚鸟类调查计划(ABC,始于1989年)覆盖了家燕亚洲种群的极小部分越冬地(Clarke et al., 1999)。

中国大陆曾开展了2项针对家燕种群数量的短期调查:江苏省苏州市浒墅关镇(1998—2001年)(潘德根,2003)、山东省济南市和泰安市的5个农村(1985—1989年)(韩云池等,1992)。其他省份几乎未见家燕种群的相关报道。全国生物多样性观测(China BON,始于2011年)涉及鸟类专题,已于2018年发布第一份观测报告,不过尚无公开数据可供查询。2017年,基于公众科学的中国家燕监测计划启动。

整体而言,现有的监测项目覆盖了家燕在欧洲和美洲的繁殖地,而亚洲繁殖地的系统监测刚刚起步。全球家燕越冬地的种群监测十分薄弱。

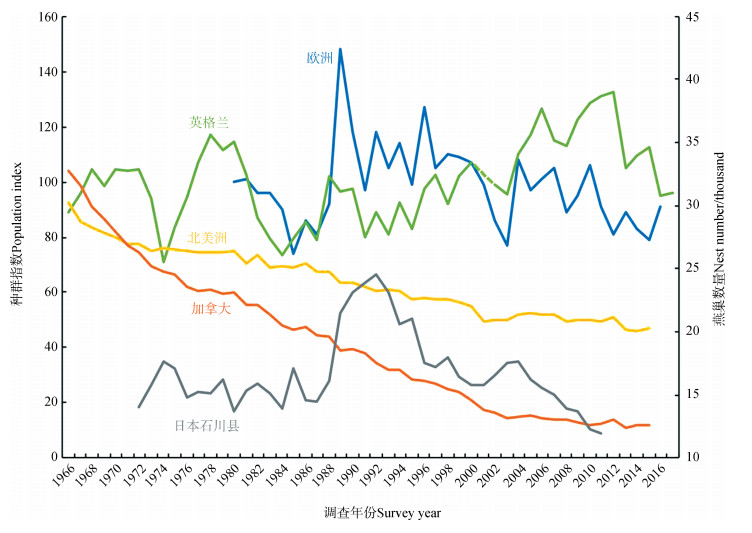

2 种群动态欧洲家燕的种群数量在1980—2016年波动明显(图 1),不过总体保持稳定(EBCC/BirdLife/RSPB/CSO,2018)。但是,种群趋势在不同区域间存在差异。例如,英格兰的家燕种群在1966—2017年存在明显的波动,但整体并无下降的趋势(Woodward et al., 2018)(图 1);而芬兰的家燕种群在1986—2012年呈下降趋势,年均下降1.4%,且2001—2012年的年均下降率增至4.2%(Laaksonen & Lehikoinen,2013)。

|

| 图 1 家燕种群动态 Fig. 1 Population dynamics of Hirundo rustica 欧洲(EBCC/BirdLife/RSPB/CSO,2018)、英格兰(Woodward et al., 2018)、北美洲(Sauer et al., 2017a)和加拿大(Sauer et al., 2017a)的家燕种群数量变化以种群指数反映(左侧坐标轴),日本石川县(Ishikawa Prefecture Health Citizens Campaign Promition Headquarters,2011)的家燕种群以燕巢数量(右侧坐标轴)来反映;不同地区种群指数的计算方法不尽相同,为了使所有指数有相似的取值范围以便于比较,北美洲和加拿大的家燕种群指数经过了转换(原指数×5~10);英格兰2001年的家燕数据缺失,以虚线代替 Europe (blue; EBCC/BirdLife/RSPB/CSO, 2018), England (green; Woodward et al., 2018), North America (yellow; Sauer et al., 2017a), Canada (orange; Sauer et al., 2017a) and Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan (grey; Ishikawa Prefecture Health Citizens Campaign Promition Headquarters, 2011); the population sizes were shown as population index (left y-axis) in all the regions except for Ishikawa Prefecture, Japan, which was shown as nest number (right y-axis); the population indexes were not calculated in the same way; thus, the original population indexes of North America and Canada were transformed by multiplying 5 and subtracting 10 (original indexes×5-10) to be comparable with other indexes; population data in 2001 was missing in England, and is shown in dashed line |

| |

北美洲家燕的种群数量在1966—2015年呈现平缓下降趋势(图 1),年均下降率1.2%,累计下降率高达44.3%(Sauer et al., 2017a);2005—2015年的年均下降率为0.9%,累计下降率8.8%。其中,加拿大的种群几乎为连续下降(图 1):年均下降3.3%,累计下降了80.8%;美国的种群呈现一定的波动,在1989年之后总体上呈下降趋势,年均下降0.5%,累计下降了16.1%(较1989年)(Sauer et al., 2017a)。与欧洲的情况相似,北美洲家燕种群变动趋势在不同的州和栖息地间存在差异。

亚洲家燕的种群变动趋势在不同地区间也存在差异。江苏省苏州市浒墅关镇的燕巢密度在1998—2001年下降了58%,整个苏南地区的燕巢数量较20世纪80年代初下降了55%(潘德根,2003)。山东省5个农村的燕巢数量在1985—1989年连续下降了63%(韩云池等,1992)。但是,其他一些地区却呈现出不同的格局。日本石川县燕巢数量在1972—2011年呈现波动(图 1)。燕巢数量在1988年之前稳定,1989—1992年连续增长,此后累计下降44%(较1989年)(Ishikawa Prefecture Health Citizens Campaign Promition Headquarters,2011)。香港燕巢数量在2004—2008年保持稳定,然而较1991年下降明显:新界元朗区的燕巢数量从72个下降到少于20个(香港观鸟会,2009)。

欧洲家燕种群总体保持稳定,北美洲家燕种群正在下降,但是种群趋势在区域和栖息地间存在差异。亚洲的家燕种群变化趋势尚待进一步研究。

不同监测时段的选取、不同监测技术及分析方法的选用(ter Braak et al., 1994)会影响对种群变化趋势的判断。如Robinson等(2003)分析英国常见鸟类调查的数据,发现1964—1998年家燕种群保持稳定,而此前Marchant(1992)提出的1976—1989年种群数量下降只是种群的波动。因此,在长期、大范围的种群监测中,不同地点的监测时段和监测技术应保持一致,种群变化趋势的分析方法应予以规范。

3 影响种群动态的因素家燕种群受气候影响会出现年际波动,主要体现在气温和降水波动对巢材和食物的影响(Royal Society for the Protection of Birds,2018)。家燕种群呈现出长期下降趋势的主要原因为全球气候变化和农业生产实践的改变(Comittee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada,2011;BirdLife International,2016;Royal Society for the Protection of Birds,2018)。农业生产实践的改变,即农业集约化(Donald et al., 2001;Newton,2004)对家燕种群数量的影响主要体现在3个方面(潘德根,2003):(1)食物来源减少,如牲畜散放被集约化饲养取代,精耕细作转变为依赖化肥和农药的机耕简作,致使家燕觅食栖息地内的昆虫减少(Ambrosini et al., 2002a, 2012);(2)适宜巢址减少,如谷仓、畜棚和房舍等木结构建筑被钢筋水泥建筑所取代,致使适宜家燕筑巢的室内折角大量消失(韩云池等,1992;Ambrosini et al., 2002a);(3)人类直接干扰增加,如破坏燕巢乃至捕杀。在我国,一些地区的村民出于卫生原因不再欢迎家燕入室筑巢,往往会封闭门窗、捣毁燕巢(赵正阶,2001)。

上述因素之间存在复杂的相互作用,且不同因素作用的时空尺度不一,造成已有研究的结论并不一致,甚至相互矛盾(Reif,2013)。气候变化导致加拿大Maritime省的家燕提前9.9 d繁殖,与此同时家燕孵化成功率下降,但是巢成功率却上升(Imlay et al., 2018)。繁殖期提前可能导致雏鸟生长期与昆虫多度的高峰期不匹配,从而影响雏鸟的生长发育(Visser et al., 2006;Both et al., 2009;Kharouba et al., 2018)。然而,Imlay等(2017)对3种燕科Hirundinidae鸟类的比较研究并不支持该观点。一个可能的解释是昆虫多度对家燕的影响在放牧活动消失的区域才会凸显出来(Ambrosini et al., 2002a)。在种群监测中,同步监测环境因子的变化可能有助于厘清不同空间尺度上环境因子的协同作用关系。

由于家燕成鸟高度忠实原巢址(Saino et al., 1999;Schaub & von Hirschheydt,2009),家燕繁殖种群规模对于环境变化的响应具有滞后性,这进一步模糊了家燕种群动态的实际影响因素。Ambrosini等(2002a, 2002b)对意大利北部家燕的研究表明:7年前的放牧状况是家燕繁殖种群分布的最佳解释因子,提示家燕对于环境变化的响应可能滞后了7年之久。因此,种群动态研究还应该囊括历史环境数据。

另一个关注较少的因素是幼鸟的扩散(Moller,1989)。家燕出生扩散受性别、体质和环境等因素影响(Scandolara et al., 2014),绝大部分幼鸟会扩散至出生地之外的区域繁殖(Balbontín et al., 2009),扩散距离的中位值达2~3 km,最大可达15.5 km(Scandolara et al., 2014),因此局地尺度上家燕的种群数量变化会受邻近种群的影响。在区域尺度上使用源-汇的理论模型(Pulliam,1988),分析后代的扩散方式与距离,可能有助于揭示种群动态及其影响因素(Tittler et al., 2006)。

4 展望作为人类最熟悉的鸟类之一,家燕具有丰富的文化和生态内涵。研究家燕有助于增进对鸟类整体的认识,也有益于加深对环境变化与动物响应的理解。借助于40~50余年的繁殖种群动态监测,家燕的种群变化趋势及其影响因素得以初步揭示,然而对于家燕的了解仍然有限。

4.1 如何在较大的时空尺度上看待家燕的种群动态?全基因组数据表明家燕与人类具有协同演化关系(Smith et al., 2018)。家燕曾利用自然环境中的洞穴、裂缝以及突出的岩石下方筑巢(Trotter,1903),约7 700年前,家燕开始适应出现的各种人类建筑,种群数量随之增加并分化为不同亚种(Smith et al., 2018)。即使在全球范围内种群下降最为严重的加拿大,家燕目前的分布面积和种群数量可能仍然高于500年前欧洲人进入美洲之前(Comittee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada,2011)。我国拥有丰富的古代文献(文榕生,2013),开展家燕的历史动物地理学研究有望描绘该物种上千年以来的分布与种群动态,助益于从更大的时空范围内看待家燕的种群变化趋势。

家燕的种群监测局限在北半球的繁殖地,很少涉及越冬地。然而,家燕已在曾经的越冬地发展出繁殖种群(Winkler et al., 2017),提示了越冬地研究的重要性。通过调整迁徙时间和路线(Winkler et al., 2017),家燕开始在阿根廷繁殖(Martínez,1983),以适应当地兴建公路桥新增的大量营巢地点。该繁殖种群在1980年首次发现时只有6对(Martínez,1983),2013年种群规模已经有几千只,分布面积近244 000 km2,且预计将进一步扩大(Grande et al., 2015;Segura,2017)。因此,真正揭示家燕的种群生态学有赖于覆盖家燕繁殖地和越冬地的大范围协同研究。日益发展的观鸟群体和公众科学有望在此发挥积极作用(Greenwood,2007;Bonney et al., 2009;Chandler et al., 2017)。

4.2 如何更好地开展中国家燕的种群监测?新近启动的中国家燕监测计划有望为家燕种群生态学提供新的资料和视角。对此提出如下建议:

(1) 长期、大范围的监测。家燕种群数量呈现波动性(图 1),并且种群趋势存在地域差异,大范围的持续监测才有助于揭示种群趋势。若调查区域小、代表性不足,则可能高估家燕种群数量下降的程度。大陆已有的2项相关研究持续时间较短(韩云池等,1992;潘德根,2003),无法准确揭示家燕的种群趋势,然而却为该物种提供了可贵的种群历史资料。建议家燕种群监测项目优先关注这些地区:江苏省的南部(苏州市、无锡市、常州市和镇江市)(潘德根,2003),山东省济南市(冯家村、大高村)、泰安市(季家庄、小官庄和西对臼)(韩云池等,1992)和日照市(李潭崖、苗家村)(高登选等,1991),便于和历史数据对比。

(2) 监测方法综合考虑家燕个体和燕巢2个途径。理想状况下,特定地区家燕个体与燕巢数量之比应该保持一致,无论哪个指标均可反映种群数量。实际上却并非如此。在日本石川县的家燕调查中,家燕个体与巢的数量之比在1972年为2.4,在2011年却降至0.98(Ishikawa Prefecture Health Citizens Campaign Promition Headquarters,2011),因此,2个指标反映出的种群变化趋势有所不同。相较而言,家燕个体数量容易监测,但是探测率受调查人员、气象条件影响较大,后期数据分析依赖复杂的统计模型(Sauer et al., 2017b);燕巢数量能可靠反映当地的家燕种群,但是入户调查实施较困难。不过,入户访谈能获得往年的数据,以及居民对家燕的态度。考虑到大陆现有的家燕种群历史资料都为燕巢数据(高登选等,1991;韩云池等,1992;潘德根,2003),实施监测项目时有必要综合利用2种监测方法。

(3) 监测环境因子的变化。鸟类监测项目的初衷即理解鸟类对环境变化(如DDT的使用)的响应,以此指导保护实践(Marchant,1983;Sauer et al., 2017b)。同步监测环境因子的变化将有助于厘清不同空间尺度上环境因子的协同作用关系,确定影响家燕种群变动的关键因素。鉴于我国的城镇化进程,城镇周边土地利用格局变化迅速,环境因子监测显得更为必要。环境因子测定依赖不同的方法和技术,比如,土地利用信息(农田面积、房屋类型)能够通过高精度遥感影像获得,气象信息(温度、降水)能够通过气象数据网(http://data.cma.cn)部分获得,放牧状况及人们对家燕的态度仍依赖人工监测。

(4) 关注金腰燕Cecropis daurica。金腰燕分布于亚、欧、非洲,与家燕的生态位相近(赵正阶,2001),因此影响家燕种群动态的因素可能也作用于金腰燕。然而,现有鸟类监测项目只涵盖了金腰燕的欧洲种群,仅涉及金腰燕全球分布范围的5%,因此,金腰燕种群趋势及威胁因子需要更大范围的研究(BirdLife International,2017)。中国是金腰燕的主要分布区,建议监测家燕种群时同步监测金腰燕。多物种的研究也有助于揭示种群变化的影响因素(Imlay et al., 2017)。

致谢: 本论文荟萃了多个鸟类监测项目的数据:北美繁殖鸟类调查(BBS)、泛欧洲常见鸟类监测计划(PECBMS)、英国繁殖鸟类调查(CBC)、日本石川县家燕调查以及香港小白腰雨燕和家燕调查。感谢上述鸟类监测项目的组织方和志愿者。感谢日本野鸟会的葉山政治惠赠英文版石川县家燕调查报告。感谢审稿人和编辑对本论文提出的宝贵意见。本论文的成型得益于第二届全国大学生生命科学竞赛提供的机会,粟多宝、赵华华、邓志芬和王娜参与了资料的收集和整理,在此一并感谢。

| 高登选, 范丰学, 陈相军. 1991. 燕子的环志观察初报[J]. 动物学杂志, 26(1): 27–30. |

| 韩云池, 李家茂, 张仲彬. 1992. 现代建筑对家燕繁殖生境的影响[J]. 野生动物(1): 12–13. |

| 环境保护部, 中国科学院. 2015.中国生物多样性红色名录——脊椎动物卷[R/OL]. (2015-05-20)[2019-02-14]. http://www.mee.gov.cn/gkml/hbb/bgg/201505/t20150525_302233.htm. |

| 潘德根. 2003. 从燕子的减少谈遵循自然规律[J]. 大自然(5): 32–33. |

| 斯幸峰, 丁平. 2011. 欧美陆地鸟类监测的历史、现状与我国的对策[J]. 生物多样性, 19(3): 303–310. |

| 田丽, 周材权, 胡锦矗. 2006. 南充金腰燕、家燕繁殖生态比较及易卵易雏实验[J]. 生态学杂志, 25(2): 170–174. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1000-4890.2006.02.012 |

| 文榕生. 2013. 中国古代野生动物地理分布[M]. 济南: 山东科学技术出版社. |

| 香港观鸟会. 2009. Survey report of house swift and barn swal low nests in Hong Kong: 2003-2008[R/OL]. [2019-02-14]. http://www.hkbws.org.hk/web/eng/swift_swallow_report_eng.html. |

| 张波. 2006. 秦皇岛地区家燕巢址选择初步研究[J]. 唐山师范学院学报, 28(2): 29–34. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1009-9115.2006.02.012 |

| 张健, 陈圣宾, 陈彬, 等. 2013. 公众科学:整合科学研究、生态保护和公众参与[J]. 生物多样性, 21(6): 738–749. |

| 赵正阶. 1982. 长白山地区家燕繁殖生态学的初步研究[J]. 动物学研究, 3(增刊): 299–303. |

| 赵正阶. 2001. 中国鸟类志下卷:雀形目[M]. 长春: 吉林科学技术出版社: 39-42. |

| 周昌乔, 李翔云. 1959. 长春地区两种燕子生态的初步观察[J]. 吉林师大学报(1): 126–136. |

| Ambrosini R, Bolzern AM, Canova L, et al. 2002a. The distribution and colony size of barn swallows in relation to agricultural land use[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 39(3): 524–534. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2664.2002.00721.x |

| Ambrosini R, Bolzern AM, Canova L, et al. 2002b. Latency in response of barn swallow Hirundo rustica populations to changes in breeding habitat conditions[J]. Ecology Letters, 5(5): 640–647. DOI:10.1046/j.1461-0248.2002.00363.x |

| Ambrosini R, Rubolini D, Trovò P, et al. 2012. Maintenance of livestock farming may buffer population decline of the barn swallow Hirundo rustica[J]. Bird Conservation International, 22(4): 411–428. DOI:10.1017/S0959270912000056 |

| Balbontín J, Møller AP, Hermosell IG, et al. 2009. Geographic patterns of natal dispersal in barn swallows Hirundo rustica from Denmark and Spain[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 63(8): 1197–1205. DOI:10.1007/s00265-009-0752-3 |

| BirdLife International. 2016. Hirundo rustica. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2016: e.T22712252A87461332[R/OL]. (2016-10-01)[2018-12-12]. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22712252A87461332.en. |

| BirdLife International. 2017. Cecropis daurica. The IUCN red list of threatened species 2017: e.T103812643A111238464[R/OL]. (2016-10-01)[2018-12-12]. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T103812643A111238464.en. |

| Bonney R, Cooper CB, Dickinson J, et al. 2009. Citizen science:a developing tool for expanding science knowledge and scientific literacy[J]. BioScience, 59(11): 977–984. DOI:10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.9 |

| Both C, Asch van M, Bijlsma RG, et al. 2009. Climate change and unequal phenological changes across four trophic levels:constraints or adaptations?[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 78(1): 73–83. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01458.x |

| Brown CR, Brown MB. 2013. Where has all the road kill gone?[J]. Current Biology, 23(6): 233–234. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.023 |

| Chandler M, See L, Copas K, et al. 2017. Contribution of citizen science towards international biodiversity monitoring[J]. Biological Conservation, 213: 280–294. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.09.004 |

| Clarke MF, Griffioen P, Loyn RH. 1999. Where do all the bush birds go?[J]. Wingspan, 9(4): Ⅰ–ⅩⅥ. |

| Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 2011. Assessment and status report on the barn swallow Hirundo rustica in Canada[R/OL]. [2019-02-14]. http://www.sararegistry.gc.ca/document/default_e.cfm?documentID=2288. |

| Donald PF, Green RE, Heath MF. 2001. Agricultural intensification and the collapse of Europe's farmland bird populations[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 268: 25–29. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2000.1325 |

| EBCC/BirdLife/RSPB/CSO. 2018. Trends of common birds in Europe, 2018 update[R/OL]. [2018-02-13]. https://pecbms.info/trends-and-indicators/species-trends. |

| Grande JM, Santillán MA, Orozco PM, et al. 2015. Barn swallows keep expanding their breeding range in South America[J]. Emu, 115(3): 256–260. DOI:10.1071/MU14097 |

| Greenwood JJD. 2007. Citizens, science and bird conservation[J]. Journal of Ornithology, 148(S1): 77–124. DOI:10.1007/s10336-007-0239-9 |

| Imlay TL, Flemming JM, Saldanha S, et al. 2018. Breeding phenology and performance for four swallows over 57 years:relationships with temperature and precipitation[J]. Ecosphere, 9(4): e02166. DOI:10.1002/ecs2.2166 |

| Imlay TL, Mann HAR, Leonard ML. 2017. No effect of insect abundance on nestling survival or mass for three aerial insectivores[J]. Avian Conservation and Ecology, 12(2): 19. DOI:10.5751/ace-01092-120219 |

| Ishikawa Prefecture Health Citizens Campaign Promition Headquarters. 2011. General survey on swallows by the children of Ishikawa prefecture[R/OL]. [2019-02-14]. http://www.pref.ishikawa.jp/seikatu/kouryu/02-2tsubame.html. |

| Kharouba HM, Ehrlén J, Gelman A, et al. 2018. Global shifts in the phenological synchrony of species interactions over recent decades[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(20): 5211–5216. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1714511115 |

| Laaksonen T, Lehikoinen A. 2013. Population trends in boreal birds:continuing declines in agricultural, northern, and long-distance migrant species[J]. Biological Conservation, 168: 99–107. DOI:10.1016/j.biocon.2013.09.007 |

| Marchant JH. 1983. Common birds census instructions[R]. Tring: British Trust for Ornithology. |

| Marchant JH. 1992. Recent trends in breeding populations of some common transe Saharan migrant birds in northern Europe[J]. IBIS, 134(S1): 113–119. |

| Martínez MM. 1983. Nesting of Hirundo rustica erythrogaster (Boddaert) in the Argentina[J]. Neotrópica, 29: 83–86. |

| Moller AP. 1989. Population dynamics of a declining swallow Hirundo rustica population[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 58(3): 1051–1063. DOI:10.2307/5141 |

| Newton I. 2004. The recent declines of farmland bird populations in Britain:an appraisal of causal factors and conservation actions[J]. IBIS, 146(4): 579–600. DOI:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2004.00375.x |

| Pagani-Núñez E, He C, Li B, et al. 2016. Breeding ecology of the barn swallow Hirundo rustica gutturalis in south China[J]. Journal of Tropical Ecology, 32(3): 260–263. DOI:10.1017/S0266467416000201 |

| Pulliam HR. 1988. Sources, sinks and population regulation[J]. The American Naturalist, 132(5): 652–661. DOI:10.1086/284880 |

| Reif J. 2013. Long-term trends in bird populations:a review of patterns and potential drivers in north America and Europe[J]. Acta Ornithologica, 48(1): 1–16. DOI:10.3161/000164513X669955 |

| Robinson RA, Crick HQP, Peach WJ. 2003. Population trends of swallows Hirundo rustica breeding in Britain[J]. Bird Study, 50(1): 1–7. DOI:10.1080/00063650309461283 |

| Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 2018. Why swallow populations fluctuate[EB/OL]. [2019-02-14]. https://www.rspb.org.uk/birds-and-wildlife/wildlife-guides/bird-a-z/swallow/population-trends/. |

| Saino N, Calza S, Ninni P, et al. 1999. Barn swallows trade survival against offspring condition and immunocompetence[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 68(5): 999–1009. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2656.1999.00350.x |

| Sauer JR, Niven DK, Hines JE, et al. 2017a. The North American breeding bird survey, results and analysis 1966-2015. Version 2.07.2017[R/OL]. Laurel, MD: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. [2019-02-14]. https://www.mbr-pwrc.usgs.gov/bbs/trend/tf15.html. |

| Sauer JR, Pardieck KL, Ziolkowski DJ, et al. 2017b. The first 50 years of the North American breeding bird survey[J]. The Condor, 119(3): 576–593. DOI:10.1650/CONDOR-17-83.1 |

| Scandolara C, Lardelli R, Sgarbi G, et al. 2014. Context-, phenotype-, and kin-dependent natal dispersal of barn swallows (Hirundo rustica)[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 25(1): 180–190. DOI:10.1093/beheco/art103 |

| Schaub M, von Hirschheydt J. 2009. Effect of current reproduction on apparent survival, breeding dispersal, and future reproduction in barn swallows assessed by multistate capture-recapture models[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 78(3): 625–635. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01508.x |

| Scordato ESC, Safran RJ. 2014. Geographic variation in sexual selection and implications for speciation in the barn swallow[J]. Avian Research, 5: 8. DOI:10.1186/s40657-014-0008-4 |

| Segura LN. 2017. Southward breeding range expansion in Argentina and first breeding record of barn swallow Hirundo rustica in Patagonia[J]. Cotinga, 39: 60–62. |

| Siriwardena GM, Baillie SR, Buckland ST, et al. 1998. Trends in the abundance of farmland birds:a quantitative comparison of smoothed indices[J]. Journal of Applied Ecology, 35(1): 24–43. |

| Smith CCR, Flaxman SM, Scordato ESC, et al. 2018. Demographic inference in barn swallows using whole-genome data shows signal for bottleneck and subspecies differentiation during the Holocene[J]. Molecular Ecology, 27(21): 4200–4212. DOI:10.1111/mec.14854 |

| ter Braak CJF, Strien van AJ, Meijer R, et al. 1994. Analysis of monitoring data with many missing values: which method?[M]// Hagemeijer W, Verstrael T. Proceeding of the 12th International Conference of IBCC and EOAC, Noordwijkerhout, The Netherlands. Voorburg/Beek-Ubbergen: Statistics Netherlands/Heerlen & SOVON: 663-673. |

| Tittler R, Fahrig L, Villard MA. 2006. Evidence of large-scale source-sink dynamics and long-distance dispersal among wood thrush populations[J]. Ecology, 87(12): 3029–3036. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[3029:EOLSDA]2.0.CO;2 |

| Trotter S. 1903. Notes on the ornithological observations of Peter Kalm[J]. Auk, XX(3): 249–262. |

| TurnerA, Christie DA. 2012. Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica)[M/OL]// del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J, et al. Handbook of the birds of the world alive. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. [2019-04-09]. https://www.hbw.com/node/57729. |

| US Fish & Wildlife Service. 2018. Endangered species[EB/OL]. [2019-02-14]. https://www.fws.gov/endangered/index.html. |

| Visser ME, Holleman LJM, Gienapp P. 2006. Shifts in caterpillar biomass phenology due to climate change and its impact on the breeding biology of an insectivorous bird[J]. Oecologia, 147(1): 164–172. DOI:10.1007/s00442-005-0299-6 |

| Winkler DW, Gandoy FA, Areta JI, et al. 2017. Long-distance range expansion and rapid adjustment of migration in a newly established population of barn swallows breeding in Argentina[J]. Current Biology, 27(7): 1080–1084. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2017.03.006 |

| Woodward ID, Massimino D, Hammond MJ, et al. 2018. BirdTrends 2018: trends in numbers, breeding success and survival for UK breeding birds[R/OL]. [2019-02-14]. http://www.bto.org/birdtrends. |

2019, Vol. 38

2019, Vol. 38