扩展功能

文章信息

- 肖繁荣, 汪继超, 史海涛

- XIAO Fanrong, WANG Jichao, SHI Haitao

- 不同生境间龟鳖类体型的差异

- Comparison of Body Size of Turtles in Different Habitats

- 四川动物, 2019, 38(2): 172-178

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2019, 38(2): 172-178

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20180256

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2018-08-21

- 接受日期: 2018-12-19

体型(即个体大小)是动物重要的形态特征,它对动物的生境利用、能量需求和生活史有着重要的影响(Cohen et al., 1993;Principe,2008)。动物体型与生境的关系在生态学和进化生物学领域备受关注(Linzmeier & Ribeiro-Costa,2011)。在诸多脊椎动物类群中,体型与家域正相关(Tershy,1992;Pyron,1999;Perry & Garland,2002)。鳄类中的大体型物种通常栖息在缺少水草的开阔生境,而小体型物种生活在热带森林的小溪流中(Farlow & Pianka,2002);占据开阔地面生境的蜥蜴物种体型较大,而占据岩石生境的物种体型较小,树丛物种的体型则介于两者之间(Collar et al., 2011)。

龟鳖类占据海洋、岛屿以及大陆的陆地和淡水等多样化生境,且体型变异大,从背甲长为10 cm的斑点陆龟Homopus signata到背甲长达200 cm的棱皮龟Dermochelys coriacea(Ernst & Lovich,2009)。这种体型差异主要受捕食压力(Arnold,1979)、种间竞争压力(Vermeij,1994)、迁徙选择(Luschi et al., 1998)、食物资源(Head et al., 2009)、生境的物理条件(Bondi & Marks,2013)和气候条件(龟鳖类贝格曼规律;Angielczyk et al., 2015)等生态因素的影响。因此,龟鳖类体型与生境存在一定的相关性。

Jaffe等(2011)研究龟鳖类体型与生境之间的关系发现,从海洋到岛屿性陆地,再到大陆性陆地和淡水生境,龟鳖类体型有逐渐变小的趋势。然而,大陆的陆地生态系统和淡水生态系统比单一的海洋或岛屿生境更复杂,如陆地生态系统包含高原、平原和荒漠等生境,淡水生态系统包含不同面积和水流速度的江河、湖泊、池塘以及山间溪流等生境。由于Jaffe等(2011)的研究主要是阐述岛屿性陆龟巨型化的原因,未对大陆陆地生态系统和淡水生态系统进行详细划分,因此尚不清楚这2种生态系统的不同生境中龟鳖类体型是否存在差异。该研究涉及226种,仅占龟鳖目Tesudines总物种数(335种;van Dijk et al., 2014)的67.5%,没有涵盖所有龟鳖类物种。本文通过收集331种龟鳖类的形态数据和生境信息,将生境分为海洋、淡水、岛屿性陆地和大陆性陆地4种类型,并将淡水生境分为5种亚类型,大陆性陆地生境分为3种亚类型,从而比较不同生境类型或亚类型之间龟鳖类体型的差异,以揭示龟鳖类体型与生境之间的关系,为龟鳖类的保护提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 数据收集本文使用龟鳖类形态指标中最常用、最稳定和最容易获得的指标——背甲长表示龟鳖类体型。参考《世界龟鳖志》(Ernst & Barbour,1989;Bonin et al., 2006)和《中国动物志爬行纲》(张孟闻等,1998)等资料,获取每一个物种的最大背甲长。由于许多龟鳖类的体型存在两性异形现象(Berry & Shine,1980;Stephens & Wiens,2009),根据Jaffe等(2011)和Angielczyk等(2015)的方法,本文收集文献中该物种最大的背甲长作为其体型指标。共收集了331种龟鳖类的体型数据,包括了龟鳖目98.8%的物种。

1.2 生境分类龟鳖类研究中常见的生境分类方法主要有5种:1)陆生和水生生境2种类型(Claude et al., 2003, 2004);2)陆生、水生和半水生生境3种类型(Benson et al., 2011);3)陆生、水生、底栖和海洋生境4种类型(Munteanu,2014);4)海洋、岛屿、淡水和大陆性陆生生境4种类型(Jaffe et al., 2011;Angielczyk et al., 2015);5)所有水域、大流水水域、小静水水域、完全陆生、陆生时常下水、陆生偶尔下水6种生境类型(Joyce & Gauthier,2004)。本研究结合上述分类方法,根据龟鳖类生境特征对其生境进行分类。参照Jaffe等(2011)和Angielczyk等(2015)的方法将龟鳖类生境分为淡水、海洋、岛屿性陆地和大陆性陆地4种类型。在Joyce和Gauthier(2004)的基础上,根据水域面积和水流速度将淡水生境分为大流水、大静水、小流水、小静水和所有水域5种亚类型。根据地形地势和干旱程度将大陆性陆地划分为平地、高地和荒漠3种亚类型。根据每一个物种的生境偏好,将其划分到上述4种类型或8种亚类型中(表 1)。

| 生境类型 Habitat type |

生境亚类型 Habitat subtype |

描述 Description |

| 淡水 | 大流水水域 | 面积大的激流水域,如大江、大河 |

| 大静水水域 | 面积大、水流缓慢或静止的水域,如湖泊、水库 | |

| 小流水水域 | 面积小的激流水域,如山间溪流 | |

| 小静水水域 | 面积小、水流缓慢或静止的水域,如池塘、沼泽 | |

| 所有水域 | 上述所有淡水水域 | |

| 大陆性陆地 | 平地 | 地势平坦的区域,如草原、平地林区和灌木丛 |

| 高地 | 地势陡峭的区域,如山地森林和灌木 | |

| 荒漠 | 极端干旱的区域,如干旱荒漠区、岩漠 |

数据的统计分析和作图分别使用SPSS 19.0和SigmaPlot 12.5完成。统计分析前对数据作对数转换,转换后的数据用于后续的统计检验。采用Kolmogorov-Smirnov检验分析所有龟鳖类以及淡水龟鳖和大陆性陆龟的体型是否符合正态分布,并作频数分布直方图。为消除系统发生对生境的影响,使用以生境类型或亚类型为固定变量,科、属(龟鳖类共14科94属;van Dijk et al., 2014)为随机变量的广义线性混合模型(generalized linear mixed model,GLMM)分析龟鳖类体型在不同生境中是否存在差异,并用Bonferroni法进行多重比较。原始数据以平均值±标准差(Mean±SD)表示,P < 0.05即认为差异有统计学意义。

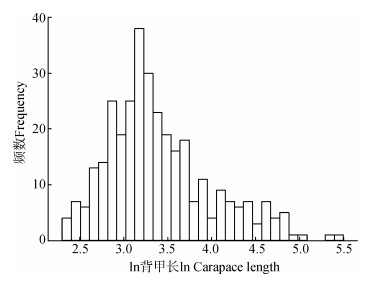

2 结果所有龟鳖类体型的Kolmogorov-Smirnov检验和直方图表明其分布不符合正态分布(n=331,Z=1.953,P=0.001;图 1),其中,海龟(n=7,Z=0.693,P=0.723)和岛屿性陆龟(n=21,Z=0.740,P=0.645)的体型符合正态分布。GLMM分析结果显示,消除系统发生的影响后,不同生境类型之间的龟鳖类体型间的差异有统计学意义(F=21.675,P < 0.000 1;图 2),其中,海龟体型最大(134.86 cm±70.14 cm),显著大于岛屿性陆龟(80.05 cm±37.11 cm;t=4.210,P < 0.000 1),岛屿性陆龟体型显著大于淡水龟鳖(32.60 cm±20.57 cm;t=3.633,P=0.001)和大陆性陆龟(27.08 cm±15.77 cm;t=5.574,P < 0.000 1),但淡水龟鳖和大陆性陆龟的差异无统计学意义(t=1.743,P=0.082)。

|

| 图 1 龟鳖类体型分布 Fig. 1 Distribution of body size of turtles |

| |

|

| 图 2 不同生境类型中龟鳖类体型的差异 Fig. 2 Differences of body size among habitat types for turtles 不同字母表示差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05);下同 Different letters denote there is a significant difference (P < 0.05); the same below |

| |

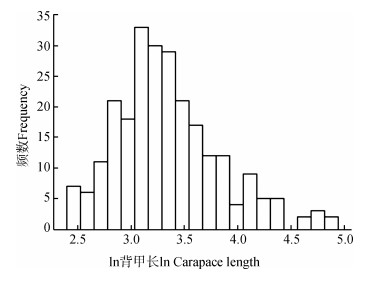

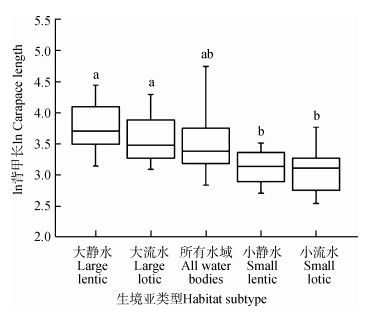

淡水龟鳖的体型符合正态分布(n=247,Z=1.342,P=0.055;图 3)。GLMM结果显示,淡水龟鳖体型在5种生境亚类型之间的差异有统计学意义(F=12.133,P < 0.000 1;图 4),其中,大静水水域的体型(50.30 cm±27.03 cm)显著大于小静水(23.78 cm±7.47 cm;t=6.101,P < 0.000 1)和小流水水域(23.79 cm±10.57 cm;t=5.776,P < 0.000 1),大流水水域的体型(39.86 cm±20.34 cm)显著大于小静水水域(t=2.943,P=0.025)和小流水水域(t=3.541,P=0.004),而大静水与大流水水域(t=2.001,P=0.233)、小静水与小流水水域(t=1.172,P=0.485)之间的差异无统计学意义(图 4)。这表明水域面积大的体型大,面积小的体型小,而静水、流水对体型无影响。广布所有淡水水域的龟鳖体型(41.50 cm±32.65 cm)比大静水(t=-1.837,P=0.269)和大流水水域(t=-0.486,P=0.627)的小,而比小静水(t=1.631,P=0.312)和小流水水域(t=2.288,P=0.138)的大,趋于中间类型,但差异无统计学意义(图 4)。

|

| 图 3 淡水龟鳖类体型分布 Fig. 3 Distribution of body size of freshwater turtles |

| |

|

| 图 4 不同生境亚类型中淡水龟鳖类体型的差异 Fig. 4 Differences of body size among habitat subtypes for freshwater turtles |

| |

大陆性陆龟的体型符合正态分布(n=56,Z=0.700,P=0.712)。大陆性陆龟的体型从高地(24.86 cm±10.09 cm)到平地(26.15 cm±20.12 cm)再到荒漠(39.11 cm±19.43 cm)生境有逐渐变大的趋势,但差异无统计学意义(F=0.238,P=0.789)。

3 讨论本研究表明,海龟体型最大,岛屿性陆龟次之,淡水龟和大陆性陆龟体型最小。这与Jaffe等(2011)的研究结论一致。海龟比其他龟鳖类体型大,主要有4个原因:1)食物链随着海洋初级生产者的数量和营养质量增加而变长,从而导致高营养级的动物进化出较大的体型(Bambach,1993;Heim et al., 2015)。2)海龟较大的体型有利于降低被大型捕食者捕食的风险。晚中生代,海洋中有大量大型沧龙类和上龙类捕食者,在这种捕食压力下,进化出了最大体型的海龟物种(Bernard et al., 2010;Motani,2010)。到新生代,较小的鲨鱼和齿鲸类成为海龟的主要捕食者,海龟体型有所减小(Lutz & Musick,1997)。然而,由于现存海洋捕食者均比其陆地的同类物种大,现存海龟依然维持较大的体型(Jaffe et al., 2011)。3)较大的体型有利于海龟季节性的长距离迁徙,如绿海龟Chelonia mydas能从大西洋的阿森松岛迁徙2 300 km到达巴西海岸(Luschi et al., 1998)。4)海龟分布区域广,从赤道到南部或北部均有分布,不同区域之间的海水温差较大,较大的体型能降低表面积与体积比以减少热量散失,从而使海龟适应低温区域的生境(Mrosovsky,1980)。

岛屿性陆龟的体型显著大于大陆性陆龟,这与Lomolino(2005)和Jaffe等(2011)研究一致。岛屿效应理论认为,受岛屿捕食压力、种间竞争压力、食物资源和迁移选择等因素的影响,岛屿动物常向巨型化或侏儒化方向进化(van Valen,1973;Lomolino,1985)。岛屿效应已在两栖爬行类、鸟类和哺乳类上得到验证(Lomolino,2005;Li et al., 2011)。岛屿上天敌数量少,种内竞争是其主要的选择压力,大体型在种内竞争占优势,从而导致岛屿物种朝巨型化方向进化(Palkovacs,2003)。岛屿性陆龟巨型化还是一种加强扩散能力的预适应,有利于祖先种群在岛屿上的早期定殖,从而促进巨型化特征稳定地遗传到后代个体中(Pritchard,1996)。同时,缺乏食草动物的岛屿环境也是导致岛屿性陆龟巨型化的重要因素,因为岛屿性陆龟为草食性动物,缺乏食性相同的竞争者(Arnold,1979)。此外,巨型化岛屿性陆龟的禁食能力较强,干旱时期有利于它们在取食场和水源地之间进行长距离的迁移(Arnold,1979;Lomolino,2005)。

大陆性陆龟与淡水龟鳖的体型之间的差异无统计学意义,这可能是水陆环境的差异对体型影响较小,而对身体形状(背甲高与背甲宽的比值)影响较大的缘故,研究表明陆生龟类的背甲高拱,而水生的背甲比较扁平,呈流线型(Romer,1967;Bonnet et al., 2010;Benson et al., 2011)。淡水龟鳖和大陆性陆龟占据从干旱荒漠到温带森林的多种水域和陆地生境,这些复杂生境中多种生态因子的综合作用也可能导致它们体型相似(Jaffe et al., 2011)。但大陆性陆龟或淡水龟鳖的多样化生境与较宽的体型之间可能存在一定关联。本研究发现大陆性陆龟的体型从高地到平地再到荒漠生境有逐渐变大的趋势。合理的解释是生活在地势陡峭岩石生境(高地)的物种需要攀爬,较小的体型有利于其灵活运动,也有利于其寻找诸如石缝这样狭小的隐蔽场所,如平顶闭壳龟Cuora mouhotii和扁平陆龟Malacochersus tornieri,而在开阔平地的陆龟则无此需求,因此体型较大(Ireland & Gans,1972;Collar et al., 2011;Xiao et al., 2017)。荒漠生境中的陆龟体型比其他2种生境的大,这可能与岛屿性陆龟一样,较大的体型有利于它们在干旱的环境中长距离迁移寻找食物和水源(Arnold,1979;Lomolino,2005)。但这种逐渐变大的趋势并不显著,可能是由于不同生境中的一些陆龟具有相同的生活习性,从而具有相似体型。如栖息于海岸线附近(平地)的纳米比亚珍龟Homopus solus和山区的扁平陆龟为适应穴居生活,体型均较小(Malonza,2003;Bonin et al., 2006)。

进一步比较淡水龟鳖在5种不同生境亚类型中的体型,发现淡水龟鳖体型与水域面积相关,水域面积大的体型大,面积小的体型小,而体型与水域是静水或流水无关。面积大的水域能承载大体型的龟鳖,并能为其提供丰富的食物资源。如黄斑巨鳖Rafetus swinhoei和鼋Pelochelys cantorii栖息在面积较大的湖泊和江河中(张孟闻等,1998),其体型显著比其他淡水龟鳖大。但分布在山间溪流、池塘等小水域的龟鳖,由于受水流量和水中食物资源的限制,生长缓慢,体型偏小。Bondi和Marks(2013)研究石斑水龟Actinemys marmorata不同种群的体型也发现相似的规律,栖息在水流量和面积较大水域的个体比在水流量和面积较小水域的个体大。此外,与海洋环境类似,淡水脊椎动物与捕食者的体型是协同进化的关系,为防止被捕食,淡水脊椎动物进化出较大的体型(Persson et al., 1996;Gaeta et al., 2018)。因此,淡水龟鳖类在面积大的水域体型较大可能与该水域现存或历史上存在大型捕食者有关。相对而言,小水域的淡水龟鳖类个体小,一方面由于其捕食者体型小,另一方面则是因为小个体的淡水龟鳖类灵活度高,掉头转身的速度快,从而能有效地逃避捕食者(Fish & Nicastro,2003;Rivera et al., 2006)。已有研究表明,流水水域的优雅伪龟Pseudemys concinna种群比静水水域的种群更呈流线型(Rivera,2008)。因此,静水或流水可能只作用在淡水龟鳖的身体形状上,而对其体型无影响,从而导致同一大小水域中流水与静水生境的龟鳖体型无显著差异。广布所有水域的龟鳖体型趋于中间型,这是为兼顾适应不同特征的淡水生境,对这些生境的利用存在权衡的结果。

本研究首次发现淡水龟鳖类的体型与水域面积有关,水域面积越大,其体型越大。这对珍稀大型淡水龟鳖类的保护具有重要的实践指导意义。如,黄斑巨鳖历史上曾经分布于我国黄河、长江、太湖和钱塘江等流域,但人类活动导致动物的栖息地丧失和破碎化,使得这些大型江河或湖泊被隔离,水域面积缩小,而该物种又不能在短时间内进化出较小体型以适应破碎的小水域,加之其他因素导致这些流域的野生个体灭绝。现存于我国境内红河流域的黄斑巨鳖,近年来由于干流梯级水电开发密度急剧下降,野生种群濒临灭绝(王剑,史海涛,2011)。本研究表明龟鳖类根据其体型适应特定的生境,大体型的淡水龟鳖占据大的水域,当其所依赖的大型水域遭到破坏,其生存将会受到影响,这是黄斑巨鳖等大型淡水龟鳖类濒临灭绝的重要原因之一。因此,要保护这些大型珍稀龟鳖类就要保护其所依赖的淡水生态系统的完整性。

致谢: 墨西哥国立自治大学(Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México)的Taggert Butterfield博士研究生对英文摘要的修改,谨致诚挚谢意。| 王剑, 史海涛. 2011. 黄斑巨鳖分布的历史变迁[J]. 动物分类学报, 36(4): 919–924. |

| 张孟闻, 宗愉, 马积藩. 1998. 中国动物志爬行纲(第Ⅰ卷)[M]. 北京: 科学出版社. |

| Angielczyk KD, Burroughs RW, Feldman CR. 2015. Do turtles follow the rules? Latitudinal gradients in species richness, body size, and geographic range area of the world's turtles:latitudinal gradients in turtles[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology, Part B:Molecular and Developmental Evolution, 324(3): 270–294. DOI:10.1002/jez.b.22602 |

| Arnold EN. 1979. Indian ocean giant tortoises:their systematics and island adaptations[J]. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 286(1011): 127–145. DOI:10.1098/rstb.1979.0022 |

| Bambach RK. 1993. Seafood through time:changes in biomass, energetics, and productivity in the marine ecosystem[J]. Paleobiology, 19(3): 372–397. DOI:10.1017/S0094837300000336 |

| Benson RBJ, Domokos G, Várkonyi P, et al. 2011. Shell geometry and habitat determination in extinct and extant turtles (Reptilia:Testudinata)[J]. Paleobiology, 37(4): 547–562. DOI:10.1666/10052.1 |

| Bernard A, Lécuyer C, Vincent P, et al. 2010. Regulation of body temperature by some Mesozoic marine reptiles[J]. Science, 328(5984): 1379–1382. DOI:10.1126/science.1187443 |

| Berry JF, Shine R. 1980. Sexual size dimorphism and selection in turtle (Order Testudins)[J]. Oecologia (Berlin), 44(2): 185–191. DOI:10.1007/BF00572678 |

| Bondi CA, Marks SB. 2013. Differences in flow regime influence the seasonal migrations, body size, and body condition of western pond turtles (Actinemys marmorata) that inhabit perennial and intermittent riverine sites in northern California[J]. Copeia, 2013(1): 142–153. DOI:10.1643/CH-12-049 |

| Bonin F, Devaux B, Dupré A. 2006. Turtles of the world[M]. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. |

| Bonnet X, Delmas V, El-Mouden H, et al. 2010. Is sexual body shape dimorphism consistent in aquatic and terrestrial chelonians?[J]. Zoology, 113(4): 213–220. DOI:10.1016/j.zool.2010.03.001 |

| Claude J, Paradis E, Tong H, et al. 2003. A geometric morphometric assessment of the effects of environment and cladogenesis on the evolution of the turtle shell[J]. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 79(3): 485–501. DOI:10.1046/j.1095-8312.2003.00198.x |

| Claude J, Prichard P, Tong H, et al. 2004. Ecological correlates and evolutionary divergence in the skull of turtles:a geometric morphometric assessment[J]. Systematic Biology, 53(6): 933–948. DOI:10.1080/10635150490889498 |

| Cohen JE, Pimm SL, Yodzis P, et al. 1993. Body sizes of animal predators and animal prey in food webs[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 62(1): 67–78. DOI:10.2307/5483 |

| Collar DC, Schulte JA, Losos JB. 2011. Evolution of extreme body size disparity in monitor lizards (Varanus)[J]. Evolution, 65(9): 2664–2680. DOI:10.1111/evo.2011.65.issue-9 |

| Ernst CH, Barbour RW. 1989. Turtles of the world[M]. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press. |

| Ernst CH, Lovich J. 2009. Turtles of the United States and Canada (2nd edition)[M]. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. |

| Farlow JO, Pianka ER. 2002. Body size overlap habitat partitioning and living space requirements of terrestrial vertebrate predators:implications for the paleoecology of large theropod dinosaurs[J]. Historical Biology, 16(1): 21–40. DOI:10.1080/0891296031000154687 |

| Fish FE, Nicastro AJ. 2003. Aquatic turning performance by the whirligig beetle:constraints on maneuverability by a rigid biological system[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 206(10): 1649–1656. DOI:10.1242/jeb.00305 |

| Gaeta JW, Ahrenstorff TD, Diana JS, et al. 2018. Go big or … don't? A field-based diet evaluation of freshwater piscivore and prey fish size relationships[J]. PLoS ONE, 13(3): e0194092. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0194092 |

| Head JJ, Bloch JI, Hastings AK, et al. 2009. Giant boid snake from the Palaeocene neotropics reveals hotter past equatorial temperatures[J]. Nature, 457(7230): 715–718. DOI:10.1038/nature07671 |

| Heim NA, Knope ML, Schaal EK, et al. 2015. Cope's rule in the evolution of marine animals[J]. Science, 347(6224): 867–870. DOI:10.1126/science.1260065 |

| Ireland LC, Gans C. 1972. The adaptive significance of the flexible shell of the tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri[J]. Animal Behaviour, 20(4): 778–781. DOI:10.1016/S0003-3472(72)80151-9 |

| Jaffe AL, Slater GJ, Alfaro ME. 2011. The evolution of island gigantism and body size variation in tortoises and turtles[J]. Biology Letters, 7(4): 558–561. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2010.1084 |

| Joyce WG, Gauthier JA. 2004. Palaeoecology of Triassic stem turtles sheds new light on turtle origins[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 271(1534): 1–5. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2003.2523 |

| Li Y, Xu F, Guo Z, et al. 2011. Reduced predator species richness drives the body gigantism of a frog species on the Zhoushan Archipelago in China[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 80(1): 171–182. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2010.01746.x |

| Linzmeier AM, Ribeiro-Costa CS. 2011. Body size of Chrysomelidae (Coleoptera) in areas with different levels of conservation in south Brazil[J]. ZooKeys(157): 1–14. |

| Lomolino MV. 1985. Body size of mammals on islands:the island rule re-examined[J]. American Naturalist, 125(2): 310–316. DOI:10.1086/284343 |

| Lomolino MV. 2005. Body size evolution in insular vertebrates:generality of the island rule[J]. Journal of Biogeography, 32(10): 1683–1699. DOI:10.1111/jbi.2005.32.issue-10 |

| Luschi P, Hays GC, Del Seppia C, et al. 1998. The navigational feats of green sea turtles migrating from Ascension Island investigated by satellite telemetry[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 265(1412): 2279–2284. DOI:10.1098/rspb.1998.0571 |

| Lutz PL, Musick JA. 1997. The biology of sea turtles[M]. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. |

| Malonza PK. 2003. Ecology and distribution of the pancake tortoise, Malacochersus tornieri in Kenya[J]. Journal of East African Natural History, 92(1): 81–96. DOI:10.2982/0012-8317(2003)92[81:EADOTP]2.0.CO;2 |

| Motani R. 2010. Warm-blooded 'sea dragons'?[J]. Science, 328(5984): 1361–1362. DOI:10.1126/science.1191409 |

| Mrosovsky N. 1980. Thermal biology of sea turtles[J]. American Zoologist, 20(3): 531–547. DOI:10.1093/icb/20.3.531 |

| Munteanu VD. 2014. Evolution of the morphology of bottom walking turtles[D]. Lewisburg, PA: Bucknell University. |

| Palkovacs EP. 2003. Explaining adaptive shifts in body size on islands:a life history approach[J]. Oikos, 103(1): 37–44. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12502.x |

| Perry G, Garland T. 2002. Lizard home ranges revisited:effects of sex, body size, diet, habitat, and phylogeny[J]. Ecology, 83(7): 1870–1885. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[1870:LHRREO]2.0.CO;2 |

| Persson L, Andersson J, Wahlstrom E, et al. 1996. Size specific interactions in lake systems:predator gape limitation and prey growth rate and mortality[J]. Ecology, 77(3): 900–911. DOI:10.2307/2265510 |

| Principe RE. 2008. Taxonomic and size structures of aquaticmacroinvertebrate assemblages in different habitats of tropical streams, Costa Rica[J]. Zoological Studies, 47(5): 525–534. |

| Pritchard PCH. 1996. The Galapagos tortoises:nomenclatural and survival status[M]. Lunenburg, MA: Chelonian Research Foundation in association with Conservation International and Chelonia Institute. |

| Pyron M. 1999. Relationships between geographical range size, body size, local abundance, and habitat breadth in North American suckers and sunfishes[J]. Journal of Biogeography, 26(3): 549–558. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2699.1999.00303.x |

| Rivera G, Rivera AR, Dougherty EE, et al. 2006. Aquatic turning performance of painted turtles (Chrysemys picta) and functional consequences of a rigid body design[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 209(21): 4203–4213. DOI:10.1242/jeb.02488 |

| Rivera G. 2008. Ecomorphological variation in shell shape of the freshwater turtle Pseudemys concinna inhabiting different aquatic flow regimes[J]. Integrative and Comparative Biology, 48(6): 769–787. DOI:10.1093/icb/icn088 |

| Romer AS. 1967. The vertebrate story[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago. |

| Stephens PR, Wiens JJ. 2009. Evolution of sexual size dimorphisms in emydid turtles:ecological dimorphism, Rensch's rule, and sympatric divergence[J]. Evolution, 63(4): 910–925. DOI:10.1111/evo.2009.63.issue-4 |

| Tershy BR. 1992. Body size, diet, habitat use, and social behavior of Balaenoptera whales in the gulf of California[J]. Journal of Mammalogy, 73(3): 477–486. DOI:10.2307/1382013 |

| van Dijk PP, Iverson JB, Rhodin AGJ, et al. 2014. Turtles of the world: annotated checklist of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution with maps, and conservation status (7th edition)[M]//Rhodin AGJ, Pritchard PCH, van Dijk PP, et al. Conservation biology of freshwater turtles and tortoises: a compilation project of the IUCN/SSC tortoise and freshwater turtle specialist group. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 5. Lunenburg, MA: Chelonian Research Foundation: 329-479. |

| van Valen L. 1973. A new evolutionary law[J]. Evolutionary Theory, 1(1): 1–30. |

| Vermeij GJ. 1994. The evolutionary interaction among species:selection, escalation, and coevolution[J]. Annual Review of Ecology & Systematics, 25(1): 219–236. |

| Xiao F, Wang J, Shi H, et al. 2017. Ecomorphological correlates of microhabitat selection in two sympatric Asian box turtle species (Geoemydidae: Cuora)[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 95(10): 753–758. DOI:10.1139/cjz-2016-0218 |

2019, Vol. 38

2019, Vol. 38