扩展功能

文章信息

- 李成容, 罗波, 王漫, 冯江

- LI Chengrong, LUO Bo, WANG Man, FENG Jiang

- 蝙蝠声音信号功能研究进展

- Research Progress on the Function of Acoustic Signals in Bats

- 四川动物, 2018, 37(6): 710-720

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2018, 37(6): 710-720

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20180151

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2018-05-10

- 接受日期: 2018-07-31

2. 东北师范大学环境学院, 吉林省动物资源保护与利用重点实验室, 长春 130117;

3. 吉林农业大学动物科学技术学院, 长春 130033

2. Jilin Provincial Key Laboratory of Animal Resource Conservation and Utilization, School of Environment, Northeast Normal University, Changchun 130117, China;

3. College of Animal Science and Technology, Jilin Agricultural University, Changchun 130033, China

声音信号影响动物的资源竞争、子代抚育、配偶选择及反捕食等系列生活史事件,是维持动物种群稳定与群落平衡的重要信息载体(Servick,2014;Ruppé et al., 2015)。动物声音信号广泛存在于陆地与水生生态系统,构成自然界绚丽的音景,如昆虫和蛙类鸣叫、鸟类鸣唱及灵长类警报叫声(Bradbury & Vehrencamp,1998)。与视觉和嗅觉信号相比,动物的声音信号具有传播距离较远、不受光照限制、易于探测和定位的优势。然而,动物声音信号也面临大气衰减、噪声掩盖及捕食者窃听等多重选择压力。开展动物声音信号功能的研究,是动物行为生态学研究的重要内容,是揭示动物表型响应环境适应性进化的关键,亦为城市化进程下物种多样性保护提供新视角(Hughes et al., 2012;Halfwerk et al., 2014;Ruppé et al., 2015)。

蝙蝠夜间活动,视觉相对退化,听觉发达,长期以来被作为声学研究的模式生物(Griffin,1944;冯江,2001;Jakobsen et al., 2013)。全世界蝙蝠超过1 300种,分为阴蝙蝠亚目Yinpterochiroptera和阳蝙蝠亚目Yangochiroptera,除狐蝠科Pteropodidae部分物种外,其余蝙蝠拥有回声定位能力(Jones & Teeling,2006)。回声定位实质是发声者发出高频回声定位声波,并接收目标的反射回声,然后在大脑中构建目标轮廓与方位的一种特殊声通讯(Ulanovsky & Moss,2008)。回声定位是蝙蝠成功占据绝大部分的全球环境,演化出丰富的物种多样性的关键行为(Jones & Teeling,2006)。值得一提的是,蝙蝠不仅利用回声定位声波进行空间导航、追踪猎物,而且利用交流声波从事社群活动、维持种群稳定(Kanwal et al., 1994;Bohn et al., 2008;Luo et al., 2013)。回声定位声波与交流声波均是蝙蝠重要的声音信号,直接影响物种存活与繁殖(Siemers & Schnitzler,2004;Gillam & Fenton,2016;Luo et al., 2017a)。

本文结合蝙蝠回声定位声波与交流声波的功能研究案例,综述当前研究现状,指明未来发展方向,以期为未来研究提供帮助与指导,进而促进我国蝙蝠行为生态学研究发展。

1 蝙蝠回声定位声波的功能回声定位一词源于Griffin(1944)在《Science》发表的“Echolocation by blind men,bats and radar”。Echolocation可分解为echo和location,其含义为利用回声、定位目标。Griffin开启了蝙蝠回声定位声波研究的新纪元。我国蝙蝠回声定位声波研究起源于20世纪末(吴飞健,陈其才,1997;张树义,冯江,1999;冯江,2001),但日益备受研究者关注。

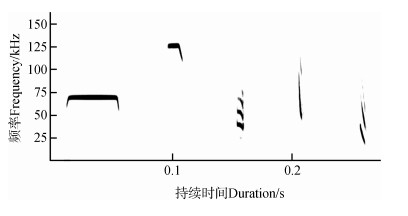

蝙蝠回声定位声波属于典型的生物声纳,是蝙蝠感知外界环境、获取食物资源的信息载体(Schnitzler et al., 2003;Ulanovsky & Moss,2008)。蝙蝠回声定位声波具有简单的声谱结构,持续时间一般为1~50 ms,主频一般为20~210 kHz。蝙蝠进化出多样的回声定位声波以适应各种复杂环境,如横频声波、多谐波窄带声波、能量集中于基频谐波的宽带声波及多谐波宽带声波(图 1)。蝙蝠通过连续发出回声定位声波,接收目标的反射回声,能够在黑暗的环境对昆虫、水体和植被成像(Simmons et al., 2014)。蝙蝠回声定位声波,尤其是捕食蜂鸣(捕捉猎物时发出的一连串急促回声定位声波),能够传递食物信息,协调社群觅食活动(Dechmann et al., 2009)。此外,蝙蝠回声定位声波也拥有社群交流功能,影响集群内部的个体和性别识别(Jones & Siemers,2010)。有关蝙蝠回声定位声波和交流声波的功能见表 1。

|

| 图 1 我国5种蝙蝠回声定位声波声谱图 Fig. 1 Spectrogram of echolocation calls from 5 bat species in China 从左至右依次为:马铁菊头蝠的长恒频声波、果树蹄蝠的短横频声波、黑髯墓蝠的多谐波窄带声波、亚洲长翼蝠的能量集中于基频谐波的宽带声波和东方蝙蝠的多谐波宽带声波;每种蝙蝠的回声定位声波由罗波在野外录制 From left to right, they are long constant-frequency call of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, short constant-frequency call of Hipposideros pomona, multiharmonic narrowband call of Taphozous melanopogon, broadband call dominated by fundamental harmonic of Miniopterus fuliginosus, and multiharmonic broadband call of Vespertilio sinensis, respectively; echolocation calls of each species are recorded by LUO Bo in the field |

| |

蝙蝠主要利用回声定位声波进行空间导航与猎物探测。声波在空气中的传播速度为340 m·s-1,蝙蝠通过回声定位声波与目标反射回声的时间延迟,能够精准测定目标的距离(Simmons et al., 1998)。目标反射回声的强度与频谱特征反映目标的大小、形状和纹理,被用于猎物识别(Simmons et al., 2014)。研究显示,蝙蝠回声定位声波碰到昆虫振动的翅膀,能够产生高强度的声波起伏,并且声波起伏周期能反映昆虫振翅频率(Kober & Schnitzler,1990;Moss & Zagaeski,1994)。不同昆虫拥有特定的振翅频率,蝙蝠能够利用回声的声波起伏辨别昆虫类型,如马铁菊头蝠Rhinolophus ferrumequinum(von der Emde & Schnitzler,1990)、印度蹄蝠Hipposideros lankadiva和大棕蝠Eptesicus fuscus(Roverud et al., 1991)。另外,昆虫翅膀反射回声的频谱特征呈现物种特异性,同种昆虫不同部位反射回声的频谱特征也略有差异,这为蝙蝠识别昆虫及其器官提供了重要声学线索(von der Emde & Schnitzler,1990;Geipel et al., 2013)。与食虫蝙蝠类似,许多植食性蝙蝠利用花瓣产生的高强度回声探测花序,觅食花蜜(von Helversen & von Helversen,1999)。蜜囊花科Marcgraviaceae植物的花序附有一种特殊碟状叶片,其回声在强度、频谱和时间特征方面与一般叶片的回声不同,这种碟状叶片提供花序独特的声学标记,使食蜜蝙蝠能够快速探测到花序,提高觅食效率(Simon et al., 2011)。

上述研究表明,蝙蝠通过回声定位能够构建猎物的高分辨率成像,在黑暗环境实现猎物的搜寻、探测和分类。然而,回声定位也面临大气衰减、猎物反捕食、声音掩盖及噪声干扰等多重选择压力。蝙蝠往往主动调节回声定位声波参数,改善猎物反射回声的质量,优化空间导航与觅食活动。许多食虫蝙蝠在觅食搜索阶段,发声持续时间较长、强度较高、带宽较小,有利于声波的远距离传播和猎物搜寻;在觅食靠近和捕捉阶段,发声持续时间较短、强度较低、带宽较大,有利于监测猎物动态、避免猎物感知声波,从而提高捕食成功率(Kalko & Schnitzler,1998;Goerlitz et al., 2010;Jakobsen et al., 2013, 2015)。蝙蝠在密闭环境中觅食,障碍物的回声、蝙蝠后续发出的回声定位声波及猎物反射回声可能发生部分重叠。因此,它们发射持续时间较短的回声定位声波,减弱声音的掩盖效应(Kalko & Schnitzler,1998)。此外,蝙蝠还能调节回声定位声波的频谱和时间参数,减弱环境噪声的干扰,如增大声波强度、持续时间和发声速率等(Hage et al., 2013;Luo et al., 2015)。总之,蝙蝠的回声定位不依赖光照,且具备极高的精度和较强的可塑性。蝙蝠能够根据觅食阶段和周边环境,调整回声定位声波参数,优化空间导航与猎物探测,最终增强个体适合度。

1.2 识别水体和植被除空间导航与猎物探测外,蝙蝠回声定位声波也用于对水体和植被的识别。Greif和Siemers(2010)以蝙蝠科Vespertilionidae、长翼蝠科Miniopterinae和菊头蝠科Rhinolophidae的15种蝙蝠作为研究对象,在室内开展水体识别实验,发现蝙蝠对光滑的金属、木板和塑料均表现出饮水行为,对粗糙的金属、木板、塑料和沙土则未出现饮水行为。Russo等(2012)选择有机玻璃和水体,在野外重复水体识别实验,发现蝙蝠科和长翼蝠科的11种蝙蝠误把有机玻璃当作水体。以上研究表明,水面反射回声的频谱特征与光滑物体反射回声的频谱特征极其相似,与粗糙物体反射回声的频谱特征截然不同,蝙蝠利用水面反射回声的频谱信息识别水体。

此外,蝙蝠可能利用回声的强度、频谱和时间特征,识别觅食生境的植被类型。Müller和Kuc(2000)选择扁平椭圆的垂叶榕Ficus benjamina树叶和针状的曼地亚红豆杉Taxus media树叶,开展声波扫描实验,量化树叶反射回声的6种声学参数,包括振幅分布的特征指数和离差、波峰因素、总能量、最大振幅、声道增益的回归系数及B-扫描的相关矩阵,发现任意2种参数能够区分2种树叶的回声,并且声道增益的回归系数和波峰因素是区分两者的关键参数。Yovel等(2008, 2009a)对森林苹果Malus sylvestris、欧洲云杉Picea abies、欧洲山毛榉Fagus sylvatica及黑刺李Prunus spinosa进行声波扫描实验,发现这4种植物的回声在频谱和时间特征方面差异显著。以上研究显示,不同植物碰到超声波产生的回声呈现种间差异,为蝙蝠识别植被类型提供声学基础。然而,蝙蝠是否能够利用回声在大脑中构建植物的三维图像仍缺乏严谨的实验证据。

1.3 协调觅食活动蝙蝠在黑暗的环境中不断发射回声定位声波探测猎物。蝙蝠回声定位声波能够指示食物资源的可利用性,为同种个体提供食物信息(Kalko & Schnitzler,1998;Fenton,2003)。Barclay(1982)在野外播放莹鼠耳蝠Myotis lucifugus觅食背景的回声定位声波,发现同种个体改变飞行方向与速度,近距离飞向声源。Gillam(2007)以空白作为对照,在野外播放巴西犬吻蝠Tadarida brasiliensis的捕食蜂鸣,发现同种个体出现数量和回声定位声波发声数量明显增多,表明巴西犬吻蝠对捕食蜂鸣的反应极为强烈。Dechmann等(2009)利用声学回放技术,证实南兔唇蝠Noctilio albiventris觅食状态的回声定位声波能吸引社群成员;无线电追踪显示,社群成员始终保持在回声定位声波的可听范围进行觅食。蝙蝠觅食背景的回声定位声波吸引同种个体,暗示回声定位声波能够传递食物信息、协调社群觅食活动。这种行为现象的机制包括3方面:第一,当蝙蝠探测到食物,它们可能发出回声定位声波来引导亲属靠近声源觅食,以提高广义适合度;第二,蝙蝠可能利用回声定位声波,促使社群成员飞向觅食地合作觅食,充分利用食物资源;第三,蝙蝠可能并非特意发出回声定位声波、传递食物信息,而是同种个体窃听发声者的回声定位声波,以缩短搜寻食物的时间、改善觅食效率(Dechmann et al., 2009)。

1.4 社群交流尽管蝙蝠回声定位声波的声谱结构比较简单,但能够编码个体和性别信息、维持社群交流。许多蝙蝠在栖息地发出个体特异的回声定位声波,如花尾蝠Euderma maculatum(Obrist,1995)、纳塔耳游尾蝠Otomops martiensseni(Fenton et al., 2004)和大鼠耳蝠Myotis myotis(Yovel et al., 2009b)。蝙蝠回声定位声波的性二态现象也见报道,一般雌性发声频率高于雄性,如帕氏髯蝠Pteronotus parnellii(Suga et al., 1987)、菲菊头蝠Rhinolophus pusillus(Jiang et al., 2010)、西班牙菊头蝠Rhinolophus mehelyi(Schuchmann et al., 2012)及马铁菊头蝠(Sun et al., 2013)。

蝙蝠能够利用回声定位声波识别集群成员。大鼠耳蝠回声定位声波的持续时间和频率参数携带个体信息,同种个体能够通过回声定位声波识别发声者(Yovel et al., 2009b)。莹鼠耳蝠的回声定位声波在持续时间、频率及声谱形状方面呈现个体差异,播放不同个体的回声定位声波能诱导实验个体改变发声速率(Kazial et al., 2008)。南兔唇蝠对同种蝙蝠的回声定位声波表现为点头、展翼和发声反应(Voigt-Heucke et al., 2010)。雌性大棕蝠对雌、雄个体的回声定位声波呈现不同发声速率(Kazial & Masters,2004)。地中海菊头蝠Rhinolophus euryale利用性别特异的回声定位声波识别发声者的性别(Schuchmann et al., 2012)。雄性大银线蝠Saccopteryx bilineata对雌性的回声定位声波表现为求偶行为,对雄性的则表现为防御行为(Knörnschild et al., 2012)。这表明,蝙蝠回声定位声波能够编码发声者的个体和性别信息,有利于社群成员传递交流信息。蝙蝠回声定位声波的社群交流功能可能受到社会选择压力的驱动。

2 蝙蝠交流声波的功能相比回声定位声波,蝙蝠交流声波具有复杂的声谱结构,持续时间一般为10~200 ms,主频往往低于20 kHz,有利于交流信息的远距离传递(Gillam & Fenton,2016)。蝙蝠在栖息地发出人耳可听的交流声波,传递饥饿、恐惧、愤怒及危险信息,介导一系列社群活动,包括社群联系、求偶与领域防御、求救呼叫及激进打斗(Kanwal et al., 1994;Gillam & Fenton,2016;Knörnschild et al., 2017)。蝙蝠交流声波类型丰富,根据发声场景分为联系叫声、求偶鸣叫、激进叫声及求救叫声(Gillam & Fenton,2016)。联系叫声是蝙蝠维持社群联系的声音信号,持续时间较长,包含纯音和噪音音节。求偶鸣叫是雄性个体的繁殖信号,持续时间极长,由正弦调频或含噪音的复合音节组成。激进叫声是指个体竞争食物和空间资源时发出的叫声,持续时间较长、频率较低。求救叫声是指个体遭遇危险时发出的叫声,持续时间中等、强度较高。蝙蝠常见的交流声波的声谱图见图 2。

|

| 图 2 蝙蝠常见的交流声波 Fig. 2 Four typical social calls in bats A.大足鼠耳蝠的激进叫声,B.菲菊头蝠的联系叫声,C.马铁菊头蝠的求救叫声,D.马铁菊头蝠的求偶鸣叫;4种交流声波由罗波在野外录制 A. aggressive call of Myotis pilosus, B. contact call of Rhinolophus pusillus, C. distress call of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum, D. courtship song of Rhinolophus ferrumequinum; four types of social calls are recorded by LUO Bo in the field |

| |

有关蝙蝠交流声波的研究可追溯到1965年,当时野外观察发现,雌性灰头狐蝠Pteropus poliocephalus发出低频交流声波,维持母婴重聚与联系(Nelson,1965)。之后,Gould(1975)报道苍白洞蝠Antrozous pallidus、大棕蝠和莹鼠耳蝠等幼仔隔离叫声的声学特征。Kanwal等(1994)借鉴鸟类鸣唱研究方法,首次系统地将蝙蝠交流声波划分为音节、短语和叫声3个层次,并且提倡通过声谱形状、持续时间和带宽命名音节类型,为后续蝙蝠交流声波研究奠定了宝贵的基础。

2.1 维持社群联系蝙蝠于日落后出飞,利用相对固定的通勤路径往返栖息地和觅食地,社群成员处于动态的分离与重聚。蝙蝠在黑暗环境有效识别社群成员、保持社群联系是亲本抚育子代的前提,也是种群繁衍与稳定的基础。研究表明,蝙蝠利用持续时间较长、声谱结构复杂的联系叫声识别亲生子代和社群成员,维持社群联系(Balcombe,1990;Chaverri et al., 2010;Gillam & Fenton,2016)。

母蝠往返觅食地和栖息地时常发出引导叫声召唤幼蝠。幼蝠能够感知母蝠的引导叫声,发出隔离叫声回应(Gould,1975;Liu et al., 2007;Jin et al., 2015)。由于幼蝠隔离叫声的频率和持续时间呈现个体特异性,母蝠能够利用隔离叫声,结合空间记忆、回声定位及嗅觉,精确定位亲生幼蝠,然后进行哺乳(Jin et al., 2015)。一些物种低度集群,是以母蝠为主导的单向识别,幼蝠无法利用母蝠叫声识别母蝠;一些物种高度集群,为母婴双向识别,母婴能够通过联系叫声识别对方。Balcombe(1990)利用2个超声波回放仪,分别播放巴西犬吻蝠亲生和非亲生幼蝠的隔离叫声,发现母蝠偏爱靠近亲生幼蝠所在的声源。Knörnschild和von Helversen(2008)选择大银线蝠母婴对作为实验对象,证实幼蝠隔离叫声的频率和带宽参数携带个体信息,并且母蝠对亲生幼蝠的隔离叫声呈现强烈识别反应。Jin等(2015)利用超声波探测仪和回放仪在果树蹄蝠Hipposideros pomona栖息地开展母婴识别实验,表明果树蹄蝠幼蝠能够利用引导叫声识别亲生母蝠。

除母婴通讯外,蝙蝠联系叫声也用于成体间的通讯。矛吻蝠Phyllostomus hastatus到达觅食地,频繁发出低频、高强度的尖叫声召唤社群成员(Wilkinson & Boughman,1998)。吸血蝠Desmodus rotundus、白翼吸血蝠Diaemus youngi和毛腿吸血蝠Diphylla ecaudata利用联系叫声维持被人为隔离后的社群联系(Carter et al., 2012)。三色盘翼蝠Thyroptera tricolor搜寻栖息地时,发出询问叫声寻求社群成员帮助,而社群成员利用应答叫声提供栖息地信息(Chaverri et al., 2010)。Furmankiewicz等(2011)在野外设置3个人工巢箱和超声波回放仪,分别播放褐山蝠Nyctalus noctula联系叫声、白噪声和空白,发现联系叫声吸引同种蝙蝠靠近人工巢箱。Arnold和Wilkinson(2011)在野外录制和回放苍白洞蝠的联系叫声,证实联系叫声能吸引同种个体靠近。

总之,蝙蝠拥有灵活的飞行能力,集群成员处于不断的分离与重聚,它们利用联系叫声传递个体与栖息地信息,以维持母婴重聚和成体联系。母蝠的引导叫声、幼蝠的隔离叫声、成体的询问叫声和应答叫声均属于联系叫声。与回声定位声波相比,蝙蝠联系叫声不仅持续时间较长,而且声谱结构较复杂,能够编码丰富的交流信息,表明联系叫声的特征与功能相适应。成体联系叫声与幼蝠隔离叫声的关系尚不清楚。我们推测,成体联系叫声可能通过幼蝠隔离叫声发育形成,这有待后续野外研究证实。

2.2 参与繁殖活动与昆虫、两栖类和鸟类相似,雄性蝙蝠在繁殖季节发出低频求偶鸣叫吸引配偶、宣示领域。求偶鸣叫是蝙蝠选择配偶的重要指标,直接影响雄性的繁殖成功率(Morell,2014)。许多蝙蝠在室内环境一般不进行繁殖活动。蝙蝠求偶鸣叫研究需要在野外选择理想的集群,结合高清红外摄像机与录音设备,长期监测集群繁殖行为,这带给研究者诸多挑战。大银线蝠为一雄多雌制,雄性个体建立领域以吸引雌性,它们栖息于废弃建筑,对实验操作低度敏感,成为求偶鸣叫研究的模式物种。Behr和Helversen(2004)在大银线蝠栖息地录制求偶鸣叫,发现求偶鸣叫由弓形调频、正弦调频及复合音节组成。Davidson和Wilkinson(2004)发现雄性大银线蝠在觅食前后频繁发出求偶鸣叫,并且求偶鸣叫的频率参数影响雄性占有的雌性数量。Behr等(2006)利用微卫星技术鉴定成年雄性大银线蝠和幼蝠的亲缘关系,发现每日发出求偶鸣叫数量越多、复合音节频率越低的个体具有越高的繁殖成功率。高速率发声在单位时间内消耗大量能量,低频叫声往往指示发声者拥有更大体型和更高主导地位(Vehrencamp,2000;Vannoni & McElligott,2008)。因此,低频、高速率的求偶鸣叫反映发声者具备优越的身体条件、占据较高的社会等级,有利于警告雄性竞争者使其远离领域,吸引成年雌性进入领域与之交配。大银线蝠的求偶鸣叫属于诚实信号,能够指示雄性个体的竞争能力,故影响雄性个体的繁殖成功率。

Knörnschild等(2010)录制并利用声波分析软件分析大银线蝠幼体和领域占有者的求偶鸣叫,发现随着幼体不断发育,幼体与领域占有者的求偶鸣叫日益相似,表明幼体学习领域占有者的求偶鸣叫。该研究还取得了另一个重要进展,即雌、雄幼体均学习领域占有者的求偶鸣叫,雄性幼体学习领域占有者的求偶鸣叫能够为后期求偶炫耀、维持领域提供声学基础;雌性幼体学习领域占有者的求偶鸣叫能够为后期评价雄性求偶鸣叫、选择优势雄性个体提供声学参考;求偶鸣叫在大银线蝠配偶选择中的作用不言而喻。目前,有关其他蝙蝠求偶鸣叫的功能尚不清楚。

2.3 防御食物和空间资源许多蝙蝠高度集群,社群成员在资源匮乏季节存在激烈的竞争。它们利用激进叫声警告竞争者,避免与之争夺食物和空间资源。蝙蝠激进叫声主要由噪音和含噪音元素的复合音节组成,频率较低、带宽较大,能够传播较远距离,表达敌意和愤怒动机,如巴西犬吻蝠(Bohn et al., 2008)、印度假吸血蝠Megaderma lyra (Bastian & Schmidt,2008)、昭短尾叶鼻蝠Carollia perspicillata (Fernandez et al., 2014)和白腹管鼻蝠Murina leucogaster (Lin et al., 2015)。蝙蝠发出激进叫声时常伴随身体接触、撕咬、打斗及飞行追逐,有利于恐吓潜在对手、垄断食物和空间资源。

野外研究显示,怀孕期和妊娠期的普通伏翼Pipistrellus pipistrellus在食物资源匮乏时,频繁发出激进叫声以维持食物斑块的占有权(Racey & Swift,1985)。Rydell(1986)野外调研发现,雌性北棕蝠Eptesicus nilssoni在觅食地发出激进叫声,可能防止其他个体竞争食物。Barlow和Jones(1997)结合昆虫调查与声学回放实验,证实普通伏翼激进叫声的发声速率随着昆虫丰富度降低而增加,并且播放激进叫声会抑制同种个体的觅食活动。Lin等(2015)报道白腹管鼻蝠利用激进叫声争夺栖息位置、驱赶社群成员。Luo等(2017a)选择东方蝙蝠Vespertilio sinensis开展精细室内实验,发现其利用长持续时间、高强度及低频的激进叫声参与食物资源的竞争。东方蝙蝠的激进叫声由长噪音音节、短噪音音节、长准恒频音节、短准恒频音节及短调频音节5种音节组成。人为减少食物资源,东方蝙蝠激进叫声的发声速率明显增加;反之,则显著降低。进一步分析显示,东方蝙蝠激进叫声的发声速率与个体每日的体质量改变和主导地位显著正相关。上述研究表明,蝙蝠激进叫声介导种内食物和空间资源的竞争,影响个体对资源利用的竞争能力,对于维持社群稳定具有重要作用。

2.4 求救叫声作为捕食者,蝙蝠食性多样,能够捕食昆虫、蜘蛛、鱼类、蛙类、果实及花粉。作为被捕食者,蝙蝠面临猛禽、浣熊、蛇及人类等的潜在威胁,甚至一些食肉蝙蝠也捕食小体型蝙蝠(Lima & O'Keefe,2013)。当蝙蝠遭遇猛禽袭击、人类束缚或被雾网困住,它们会发出高强度的求救叫声,通知社群成员实施营救。目前,研究者报道了6科16种蝙蝠求救声波的特征,包括蝙蝠科(Fenton et al., 1976)、矛吻蝠科Phyllostominae(August,1979)、长翼蝠科(Russ et al., 2004)、狐蝠科(Ganesh et al., 2010)、菊头蝠科(Luo et al., 2013)及鞘尾蝠科Emballonuridae(Luo et al., 2013;Eckenweber & Knörnschild,2016)。

Fenton等(1976)首次在莹鼠耳蝠栖息地回放求救叫声,引起同种个体在声源附近盘旋飞行。Russ等(1998, 2004)在3种伏翼栖息地附近播放各自的求救叫声,发现求救叫声吸引同种和异种个体,引发类似聚众滋扰的反捕食行为。Carter等(2015)报道獒蝠Molossus molossus求救叫声会吸引同种个体和同域分布的大银线蝠,同时发现被吸引的蝙蝠始终与声源维持一段距离,暗示这些蝙蝠可能靠近声源调查情况,并非驱赶潜在捕食者。Huang等(2015)在大趾鼠耳蝠Myotis macrodactylus栖息洞穴安装摄像与录音装置,发现大趾鼠耳蝠在撞网阶段表现为撕咬和拍翼行为,在实验者靠近和捕捉阶段发出求救叫声和回声定位声波;亚成体倾向于选择发声的求助策略,而成体倾向于选择撕咬和拍翼的防御策略。

整体而言,蝙蝠求救叫声可能具有多重功能,在反捕食行为中有重要作用。一些蝙蝠的求救叫声能够吸引同种和异种个体靠近声源,合作驱逐潜在捕食者,有利于提高发声者的存活概率、恢复集群的正常活动。一些蝙蝠的求救叫声并非吸引亲属和社群成员实施营救,而是警告信号接收者远离声源,引起警惕和躲避行为。一些蝙蝠发出求救叫声,伴随高强度的撕咬和拍翼行为,可能反映发声者的防御能力、惊吓捕食者。无论是哪种解释,蝙蝠发出求救叫声能够作为一种反捕食策略,是对捕食风险的适应性响应。

3 未来展望综上所述,蝙蝠是一类夜行性的集群哺乳动物,主要利用声音信号进行觅食和社群活动,为声学研究的模式类群(冯江,2001;Kunz & Fenton,2003;Luo et al., 2017b;Thiagavel et al., 2018)。蝙蝠声音信号的功能是行为生态学研究的重要内容,能够阐明蝙蝠声音信号的产生及其多样性维持机制,为城市化进程下蝙蝠物种多样性保育提供理论指导。国际蝙蝠声音信号研究始于19世纪40年代,经过近80年快速发展,研究者已经阐明蝙蝠回声定位声波在探测猎物、感知物体、协调觅食及传递交流信息方面具有重要作用。另外,研究者揭示了蝙蝠交流声波介导社群联系、资源竞争、繁殖活动及反捕食行为(Fenton, 2003, 2013)。然而,有关蝙蝠声音信号的功能仍存诸多疑问。

未来研究将聚焦下列科学问题。第一,交通车辆、机械施工、降雨和风等引起的噪声普遍存在于生态系统,这些噪声虽为人耳可听声,但也具有一些超声成分。蝙蝠如何调整声音信号的持续时间、频率、强度及声束,应对噪声的掩盖效应,优化空间导航、觅食探测及社群交流,有待进一步研究。尽管有研究已经关注噪声对笼养蝙蝠回声定位的影响(Hage et al., 2013;Luo et al., 2015),但自然状态下蝙蝠如何改变回声定位声波参数应对噪声干扰仍被普遍忽视,蝙蝠如何改变交流声波参数减弱噪声的掩盖效应仍不清楚,不同物种应对噪声干扰的声学策略及其影响机制也有待系统比较。第二,蝙蝠回声定位声波与交流声波影响资源获取与竞争、亲本抚育、社群联系及配偶选择等关键生活史事件,2种声音信号与个体适合度的关系尚不得而知,长时间尺度量化蝙蝠声音信号与适合度的关系十分必要。第三,目前仅发现一雄多雌制的雄性大银线蝠发出求偶鸣叫吸引雌性、防御领域。其他雄性蝙蝠是否利用求偶鸣叫参与繁殖活动有待进一步证实。第四,回声定位声波与交流声波均是蝙蝠重要的声音信号,两者影响蝙蝠的资源利用、配偶识别及社群稳定,可能促进物种形成(Jones,1997)。有关2种声音信号与蝙蝠物种形成速率的关系有待进一步探究。

致谢: 感谢东北师范大学蝙蝠重点实验室全体成员对研究的帮助和指导。| 冯江. 2001. 蝙蝠回声定位行为生态研究[M]. 长春: 吉林科学技术出版社. |

| 吴飞健, 陈其才. 1997. 蝙蝠听觉器的"视"功能[J]. 生物学通报, 32(7): 16–18. |

| 张树义, 冯江. 1999. 三种蝙蝠飞行状态下回声定位信号的比较[J]. 动物学报, 45(4): 385–389. |

| Arnold BD, Wilkinson GS. 2011. Individual specific contact calls of pallid bats (Antrozous pallidus) attract conspecifics at roosting sites[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 65(8): 1581–1593. DOI:10.1007/s00265-011-1168-4 |

| August P. 1979. Distress calls in Artibeus jamaicensis: ecology and evolutionary implications[M]//Eisenberg JF. Vertebrate ecology in the northern Neotropics. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press: 151-159. |

| Balcombe JP. 1990. Vocal recognition of pups by mother Mexican free-tailed bats, Tadarida brasiliensis mexicana[J]. Animal Behaviour, 39(5): 960–966. DOI:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80961-3 |

| Barclay RMR. 1982. Interindividual use of echolocation calls: eavesdropping by bats[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 10(4): 271–275. DOI:10.1007/BF00302816 |

| Barlow KE, Jones G. 1997. Function of pipistrelle social calls: field data and a playback experiment[J]. Animal Behaviour, 53(5): 991–999. DOI:10.1006/anbe.1996.0398 |

| Bastian A, Schmidt S. 2008. Affect cues in vocalizations of the bat, Megaderma lyra, during agonistic interactions[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 124(1): 598–608. DOI:10.1121/1.2924123 |

| Behr O, Helversen O. 2004. Bat serenades-complex courtship songs of the sac-winged bat (Saccopteryx bilineata)[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 56(2): 106–115. DOI:10.1007/s00265-004-0768-7 |

| Behr O, von Helversen O, Heckel G, et al. 2006. Territorial songs indicate male quality in the sac-winged bat Saccopteryx bilineata (Chiroptera, Emballonuridae)[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 17(5): 810–817. DOI:10.1093/beheco/arl013 |

| Bohn KM, Schmidt-French B, Ma ST, et al. 2008. Syllable acoustics, temporal patterns, and call composition vary with behavioral context in Mexican free-tailed bats[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 124(3): 1838–1848. DOI:10.1121/1.2953314 |

| Bradbury J, Vehrencamp SL. 1998. Principles of animal communication[M]. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates. |

| Carter GG, Logsdon R, Arnold BD, et al. 2012. Adult vampire bats produce contact calls when isolated: acoustic variation by species, population, colony, and individual[J]. PLoS ONE, 7(6): e38791. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0038791 |

| Carter G, Schoeppler D, Manthey M, et al. 2015. Distress calls of a fast-flying bat (Molossus molossus) provoke inspection flights but not cooperative mobbing[J]. PLoS ONE, 10(9): e0136146. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0136146 |

| Chaverri G, Gillam EH, Vonhof MJ. 2010. Social calls used by a leaf-roosting bat to signal location[J]. Biology Letters, 6(4): 441–444. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0964 |

| Davidson SM, Wilkinson GS. 2004. Function of male song in the greater white-lined bat, Saccopteryx bilineata[J]. Animal Behaviour, 67(5): 883–891. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.06.016 |

| Dechmann DKN, Heucke SL, Giuggioli L, et al. 2009. Experimental evidence for group hunting via eavesdropping in echolocating bats[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 276(1668): 2721–2728. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2009.0473 |

| Eckenweber M, Knörnschild M. 2016. Responsiveness to conspecific distress calls is influenced by day-roost proximity in bats (Saccopteryx bilineata)[J]. Royal Society Open Science, 3(5): 160151. DOI:10.1098/rsos.160151 |

| Fenton MB, Belwood JJ, Fullard JH, et al. 1976. Responses of Myotis lucifugus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) to calls of conspecifics and to other sounds[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 54(9): 1443–1448. DOI:10.1139/z76-167 |

| Fenton MB, Jacobs DS, Richardson EJ, et al. 2004. Individual signatures in the frequency-modulated sweep calls of African large-eared, free-tailed bats Otomops martiensseni (Chiroptera: Molossidae)[J]. Journal of Zoology, 262(1): 11–19. DOI:10.1017/S095283690300431X |

| Fenton MB. 2003. Eavesdropping on the echolocation and social calls of bats[J]. Mammal Review, 33(3): 193–204. |

| Fenton MB. 2013. Questions, ideas and tools: lessons from bat echolocation[J]. Animal Behaviour, 85(5): 869–879. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.02.024 |

| Fernandez AA, Fasel N, Knörnschild M, et al. 2014. When bats are boxing: aggressive behaviour and communication in male Seba's short-tailed fruit bat[J]. Animal Behaviour, 98: 149–156. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.10.011 |

| Furmankiewicz J, Ruczyński I, Urban R, et al. 2011. Social calls provide tree-dwelling bats with information about the location of conspecifics at roosts[J]. Ethology, 117: 480–489. DOI:10.1111/eth.2011.117.issue-6 |

| Ganesh A, Raghuram H, Nathan PT, et al. 2010. Distress call-induced gene expression in the brain of the Indian short-nosed fruit bat, Cynopterus sphinx[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 196(2): 155–164. |

| Geipel I, Jung K, Kalko EKV. 2013. Perception of silent and motionless prey on vegetation by echolocation in the gleaning bat Micronycteris microtis[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 280(1754): 20122830. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2012.2830 |

| Gillam E, Fenton MB. 2016. Roles of acoustic social communication in the lives of bats[M]//Fenton BM, Grinnell DA, Popper NA, et al. Bat bioacoustics. New York: Springer: 117-139. |

| Gillam EH. 2007. Eavesdropping by bats on the feeding buzzes of conspecifics[J]. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 85(7): 795–801. DOI:10.1139/Z07-060 |

| Goerlitz HR, ter Hofstede HM, Zeale MR, et al. 2010. An aerial-hawking bat uses stealth echolocation to counter moth hearing[J]. Current Biology, 20(17): 1568–1572. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2010.07.046 |

| Gould E. 1975. Neonatal vocalizations in bats of eight genera[J]. Journal of Mammalogy, 56(1): 15–29. DOI:10.2307/1379603 |

| Greif S, Siemers BM. 2010. Innate recognition of water bodies in echolocating bats[J]. Nature Communications, 1(1): 107. DOI:10.1038/ncomms1110 |

| Griffin DR. 1944. Echolocation by blind men, bats and radar[J]. Science, 100(2609): 589–590. DOI:10.1126/science.100.2609.589 |

| Hage SR, Jiang TL, Berquist SW, et al. 2013. Ambient noise induces independent shifts in call frequency and amplitude within the Lombard effect in echolocating bats[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(10): 4063–4068. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1211533110 |

| Halfwerk W, Jones P, Taylor R, et al. 2014. Risky ripples allow bats and frogs to eavesdrop on a multisensory sexual display[J]. Science, 343(2609): 413–416. |

| Huang XB, Kanwal JS, Jiang TL, et al. 2015. Situational and age-dependent decision making during life threatening distress in Myotis macrodactylus[J]. PLoS ONE, 10(7): e0132817. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0132817 |

| Hughes NK, Kelley JL, Banks PB. 2012. Dangerous liaisons: the predation risks of receiving social signals[J]. Ecology Letters, 15(11): 1326–1339. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01856.x |

| Jakobsen L, Olsen MN, Surlykke A. 2015. Dynamics of the echolocation beam during prey pursuit in aerial hawking bats[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112(26): 8118–8123. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1419943112 |

| Jakobsen L, Ratcliffe JM, Surlykke A. 2013. Convergentacoustic field of view in echolocating bats[J]. Nature, 493(7430): 93–96. |

| Jiang TL, Metzner W, You YY, et al. 2010. Variation in the resting frequency of Rhinolophus pusillus in mainland China: effect of climate and implications for conservation[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 128(4): 2204–2211. DOI:10.1121/1.3478855 |

| Jin LR, Yang SL, Kimball RT, et al. 2015. Do pups recognize maternal calls in pomona leaf-nosed bats, Hipposideros pomona?[J]. Animal Behaviour, 100: 200–207. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.12.006 |

| Jones G, Siemers BM. 2010. The communicative potential of bat echolocation pulses[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 197(5): 447–457. |

| Jones G, Teeling E. 2006. The evolution of echolocation in bats[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 21(3): 149–156. |

| Jones G. 1997. Acoustic signals and speciation: the roles of natural and sexual selection in the evolution of cryptic species[J]. Advances in the Study of Behaviour, 26(8): 317–354. |

| Kalko EK, Schnitzler H. 1998. How echolocating bats approach and acquire food[M]//Kunz TH, Racey PA. Bat biology and conservation. London: Smithsonian Institution Press: 197-204. |

| Kanwal JS, Matsumura S, Ohlemiller K, et al. 1994. Analysis of acoustic elements and syntax in communication sounds emitted by mustached bats[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 96(3): 1229–1254. DOI:10.1121/1.410273 |

| Kazial KA, Kenny TL, Burnett SC. 2008. Little brown bats (Myotis lucifugus) recognize individual identity of conspecifics using sonar calls[J]. Ethology, 114(5): 469–478. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2008.01483.x |

| Kazial KA, Masters WM. 2004. Female big brown bats, Eptesicus fuscus, recognize sex from a caller's echolocation signals[J]. Animal Behaviour, 67(5): 855–863. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.016 |

| Knörnschild M, Blüml S, Steidl P, et al. 2017. Bat songs as acoustic beacons-male territorial songs attract dispersing females[J]. Scientific Reports, 7: 13918. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-14434-5 |

| Knörnschild M, Jung K, Nagy M, et al. 2012. Bat echolocation calls facilitate social communication[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 279(1748): 4827–4835. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2012.1995 |

| Knörnschild M, Nagy M, Metz M, et al. 2010. Complex vocal imitation during ontogeny in a bat[J]. Biology Letters, 6(2): 156–159. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0685 |

| Knörnschild M, von Helversen O. 2008. Nonmutual vocal mother-pup recognition in the greater sac-winged bat[J]. Animal Behaviour, 76(3): 1001–1009. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.05.018 |

| Kober R, Schnitzler HU. 1990. Information in sonar echoes of fluttering insects available for echolocating bats[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 87(2): 882–896. DOI:10.1121/1.398898 |

| Kunz TH, Fenton MB. 2003. Bat ecology[M]. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. |

| Lima SL, O'Keefe JM. 2013. Do predators influence the behaviour of bats?[J]. Biological Reviews, 88(3): 626–644. DOI:10.1111/brv.2013.88.issue-3 |

| Lin HJ, Kanwal JS, Jiang TL, et al. 2015. Social and vocal behavior in adult greater tube-nosed bats (Murina leucogaster)[J]. Zoology, 118(3): 192–202. DOI:10.1016/j.zool.2014.12.005 |

| Liu Y, Feng J, Jiang YL, et al. 2007. Vocalization development of greater horseshoe bat, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum (Rhinolophidae, Chiroptera)[J]. Folia Zoologica, 56(2): 126–136. |

| Luo B, Huang XB, Li YY, et al. 2017b. Social call divergence in bats: a comparative analysis[J]. Behavioral Ecology, 28(2): 533–540. |

| Luo B, Jiang TL, Liu Y, et al. 2013. Brevity is prevalent in bat short-range communication[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 199(4): 325–333. DOI:10.1007/s00359-013-0793-y |

| Luo B, Lu GJ, Chen K, et al. 2017a. Social calls honestly signal female competitive ability in Asian particoloured bats[J]. Animal Behaviour, 127: 101–108. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.03.012 |

| Luo JH, Goerlitz HR, Brumm H, et al. 2015. Linking the sender to the receiver: vocal adjustments by bats to maintain signal detection in noise[J]. Scientific Reports, 5: 18556. DOI:10.1038/srep18556 |

| Müller R, Kuc R. 2000. Foliage echoes: a probe into the ecological acoustics of bat echolocation[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 108(2): 836–845. DOI:10.1121/1.429617 |

| Morell V. 2014. When the bat sings[J]. Science, 344(6190): 1334–1337. DOI:10.1126/science.344.6190.1334 |

| Moss CF, Zagaeski M. 1994. Acoustic information available to bats using frequency-modulated sounds for the perception of insect prey[J]. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 95(5): 2745–2756. DOI:10.1121/1.409843 |

| Nelson JE. 1965. Behaviour of Australian pteropodidae (Megacheroptera)[J]. Animal Behaviour, 13(4): 544–557. DOI:10.1016/0003-3472(65)90118-1 |

| Obrist MK. 1995. Flexible bat echolocation: the influence of individual, habitat and conspecifics on sonar signal design[J]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 36(3): 207–219. DOI:10.1007/BF00177798 |

| Racey PA, Swift SM. 1985. Feeding ecology of Pipistrellus pipistrellus (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae) during pregnancy and lactation. Ⅰ. Foraging behaviour[J]. Journal of Animal Ecology, 54(1): 205–215. DOI:10.2307/4631 |

| Roverud RC, Nitsche V, Neuweiler G. 1991. Discrimination of wingbeat motion by bats, correlated with echolocation sound pattern[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 168(2): 259–263. |

| Ruppé L, Clément G, Herrel A, et al. 2015. Environmental constraints drive the partitioning of the soundscape in fishes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 112(19): 6092–6097. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1424667112 |

| Russ J, Racey P, Jones G. 1998. Intraspecific responses to distress calls of the pipistrelle bat, Pipistrellus pipistrellus[J]. Animal Behaviour, 55(3): 705–713. DOI:10.1006/anbe.1997.0665 |

| Russ J, Jones G, Mackie I, et al. 2004. Interspecific responses to distress calls in bats (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae): a function for convergence in call design?[J]. Animal Behaviour, 67(6): 1005–1014. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.09.003 |

| Russo D, Cistrone L, Jones G. 2012. Sensory ecology of water detection by bats: a field experiment[J]. PLoS ONE, 7(10): e48144. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0048144 |

| Rydell J. 1986. Feeding territoriality in female northern bats, Eptesicus nilssoni[J]. Ethology, 72(4): 329–337. |

| Schnitzler HU, Moss CF, Denzinger A. 2003. From spatial orientation to food acquisition in echolocating bats[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18(8): 386–394. |

| Schuchmann M, Puechmaille SJ, Siemers BM. 2012. Horseshoe bats recognise the sex of conspecifics from their echolocation calls[J]. Acta Chiropterologica, 14(1): 161–166. DOI:10.3161/150811012X654376 |

| Servick K. 2014. Eavesdropping on ecosystems[J]. Science, 343(6173): 834–837. DOI:10.1126/science.343.6173.834 |

| Siemers BM, Schnitzler HU. 2004. Echolocation signals reflect niche differentiation in five sympatric congeneric bat species[J]. Nature, 429(6992): 657–661. DOI:10.1038/nature02547 |

| Simmons JA, Ferragamo MJ, Moss CF. 1998. Echo-delay resolution in sonar images of the big brown bat, Eptesicus fuscus[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(21): 12647–12652. DOI:10.1073/pnas.95.21.12647 |

| Simmons JA, Houser D, Kloepper L. 2014. Localization and classification of targets by echolocating bats and dolphins[M]//Surlykke A, Nachtigall EP, Fay RR, et al. Biosonar. New York: Springer: 169-193. |

| Simon R, Holderied MW, Koch CU, et al. 2011. Floral acoustics: conspicuous echoes of a dish-shaped leaf attract bat pollinators[J]. Science, 333(6042): 631–633. DOI:10.1126/science.1204210 |

| Suga N, Niwa H, Taniguchi I, et al. 1987. The personalized auditory cortex of the mustached bat: adaptation for echolocation[J]. Journal of Neurophysiology, 58(4): 643–654. DOI:10.1152/jn.1987.58.4.643 |

| Sun KP, Luo L, Kimball RT, et al. 2013. Geographic variation in the acoustic traits of greater horseshoe bats: testing the importance of drift and ecological selection in evolutionary processes[J]. PLoS ONE, 8(8): e70368. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0070368 |

| Thiagavel J, Cechetto C, Santana SE, et al. 2018. Auditory opportunity and visual constraint enabled the evolution of echolocation in bats[J]. Nature Communications, 9(1): 98. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-02532-x |

| Ulanovsky N, Moss CF. 2008. What the bat's voice tells the bat's brain[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(205): 8491–8498. |

| Vannoni E, McElligott AG. 2008. Low frequency groans indicate larger and more dominant fallow deer (Dama dama) males[J]. PLoS ONE, 3(9): e3113. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0003113 |

| Vehrencamp SL. 2000. Handicap, index, and conventional signal elements of bird song[M]//Espmark Y, Amundsen T, Rosenqvist G. Animal signals: signalling and signal design in animal communication. Norway: Tapir Academic Press: 277-300. |

| Voigt-Heucke SL, Taborsky M, Dechmann DKN. 2010. A dual function of echolocation: bats use echolocation calls to identify familiar and unfamiliar individuals[J]. Animal Behaviour, 80(1): 59–67. DOI:10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.03.025 |

| von derEmde G, Schnitzler HU. 1990. Classification of insects by echolocating greater horseshoe bats[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, 167(3): 423–430. DOI:10.1007/BF00192577 |

| von Helversen D, von Helversen O. 1999. Acoustic guide in bat-pollinated flower[J]. Nature, 398: 759–760. DOI:10.1038/19648 |

| Wilkinson GS, Boughman JW. 1998. Social calls coordinate foraging in greater spear-nosed bats[J]. Animal Behaviour, 55(2): 337–350. DOI:10.1006/anbe.1997.0557 |

| Yovel Y, Franz MO, Stilz P, et al. 2008. Plant classification from bat-like echolocation signals[J]. PLoS Computational Biology, 4(3): e1000032. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000032 |

| Yovel Y, Melcon ML, Franz MO, et al. 2009b. The voice of bats: how greater mouse-eared bats recognize individuals based on their echolocation calls[J]. PLoS Computational Biology, 5(6): e1000400. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000400 |

| Yovel Y, Stilz P, Franz MO, et al. 2009a. What a plant sounds like: the statistics of vegetation echoes as received by echolocating bats[J]. PLoS Computational Biology, 5(7): e1000429. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000429 |

2018, Vol. 37

2018, Vol. 37