扩展功能

文章信息

- 李相涛, 王燕, 李梅, 门胜康, 蒲鹏, 唐晓龙, 陈强

- LI Xiangtao, WANG Yan, LI Mei, MEN Shengkang, PU Peng, TANG Xiaolong, CHEN Qiang

- 不同海拔两种沙蜥低温耐受性的比较

- Comparison of Cold Hardiness of Two Toad-headed Lizards from Different Altitudes

- 四川动物, 2017, 36(3): 300-305

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2017, 36(3): 300-305

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20170014

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-01-12

- 接受日期: 2017-03-14

变温动物的地理分布受气温、湿度和氧浓度(Krebs,1974;Campbell & Solorzano,1992;Gaston,2003)等诸多环境因素的影响,其中气温是相当重要的(Stuart,1951;Graham et al., 1971;Huang et al., 2006),因为变温动物的体温很大程度上取决于自然环境下的热交换(Pough,1980)。由于气温随海拔的升高而降低,与低海拔物种相比,高海拔的变温动物将会经历更低的气温(Damme et al., 1989, 1990;Grant & Dunham,1990;Smith & Ballinger,1994;Navas,2002)。寒冷环境对所有生物尤其是变温动物提出了许多挑战(Cossins,2012)。许多以冬眠方式过冬的生物面临着能量短缺的风险,越冬过程中能量的短缺能够导致死亡或繁殖能力降低(Irwin & Lee,2003;Hahn & Denlinger,2011),并且限制了一些物种的分布(Humphries et al., 2002)。因此,冬季的长度和严酷程度对于陆生动物都是挑战。

不能逃离冰冻环境的变温动物一般有2种低温存活策略,即避免结冰和耐受结冰。在大多数情况下,这2种方式是相互排斥的(Costanzo & Lee,2013)。避免结冰策略使动物体液在气温低于体液的均衡结冰点(溶液在降温过程中结冰时的最高温度)时保持液态;耐受结冰策略使生物体能够忍受部分体液转化成冰(Sømme,1982;Storey & Storey,1988)。目前,在低温耐受方面研究最多的蜥蜴类是胎生蜥蜴Zootoca vivipara。有报道指出Weigmann是在脊椎动物中证实结冰耐受的第一人,而欧洲的普通壁蜥Podarcis muralis是被发现的第一个表现出耐受结冰的脊椎动物(Weigmann,1929;Claussen et al., 1990)。实验室条件下的研究结果表明,胎生蜥蜴可以在过冷状态下存活3周或者在结冰状态下存活3 d(Costanzo et al., 1995)。

结冰前、结冰过程中或结冰后,有机物质的积累在保护细胞和组织对抗结冰/解冻的压力上起重要作用。避免结冰的物种通过积累多种渗透物质,包括多元醇、糖类和特定的氨基酸等来降低组织的结冰/融化温度(Storey & Storey,1988;Lee,2010)。甘油、葡萄糖、乳酸和尿素4种渗透物质作为被证实了的抗冻保护剂被结冰耐受的脊椎动物广泛使用(Costanzo & Lee,2013)。其中,葡萄糖可以依数性(取决于溶液中的粒子数量而非性质)减少冰含量的增加以及细胞的缩水,能够对细胞膜和蛋白质起到特定的保护作用(Costanzo & Lee,2013);树蛙Rana sylvatica冬眠时会在组织中积累尿素(Schiller et al., 2008);冷驯化的灰树蛙Hyla chrysoscelis血浆中甘油的浓度可以由≈1 mmol·L-1上升至50~80 mmol·L-1甚至更多(Zimmerman et al., 2007;Layne & Stapleton,2009);结冰耐受的爬行动物在结冰时也会合成渗透物质(主要是葡萄糖和乳酸)(Storey,2006;Costanzo et al., 2008)。

红尾沙蜥Phrynocephalus erythrurus栖息于西藏北部的羌塘高原地区,被认为是世界上垂直分布最高的蜥蜴(海拔4 500~5 300 m)(Zhao & Adler,1993;Jin & Liu,2010),而且其生存环境恶劣,冬季月平均气温可达到-15 ℃以下。本研究选择红尾沙蜥为主要研究对象,同时以生活在低海拔地区的荒漠沙蜥P. przewalskii作为参照,测定了不同海拔2种沙蜥的过冷能力、对于接种结冰的耐受能力、急性低温(4 ℃)条件下的心率和呼吸频率,以及体内可能作为抗冻保护剂存在的4种小分子渗透物质。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验动物2016年5月于青海省格尔木市唐古拉山镇(92°13′E,34°13′N,海拔4 543 m)捕获34只成体红尾沙蜥;荒漠沙蜥于2016年4月底在甘肃省民勤县(103°05′E,38°38′N,海拔1 482 m)捕获。

1.2 蜥蜴过冷能力的测定蜥蜴称量后,将经过水银温度计矫正的热电偶用医用胶带贴在蜥蜴的胸腹部,进行温度的实时监控。然后用干燥的棉花将蜥蜴包着放入50 mL的塑料离心管中。最后把蜥蜴放在以酒精为介质的低温冷浴中,初始温度为4 ℃,1 h后以0.5 ℃/h的速率进行降温,直至放热曲线出现。此时的温度作为蜥蜴的过冷能力。

1.3 蜥蜴对于接种结冰耐受能力的检测蜥蜴称量后,将经过水银温度计矫正的热电偶用医用胶带贴在蜥蜴的胸腹部,然后将蜥蜴用采自沱沱河的湿沙(含水量4.23%)包围着放入50 mL的塑料离心管中。将蜥蜴放在以酒精为介质的低温冷浴中,初始温度为4 ℃,1 h后以0.5 ℃/h的速率进行降温,直至放热曲线出现。此时的温度作为蜥蜴对于接种结冰的耐受能力。

1.4 4 ℃条件下蜥蜴心率和呼吸频率的测定随机选取成体红尾沙蜥和荒漠沙蜥各10只,在避光、恒温(4 ℃)条件下通过BL420-F生物采集分析系统(成都泰盟科技有限公司)记录蜥蜴体温、心率和呼吸频率。

1.5 渗透物质的检测随机选取2种沙蜥各8只,双毁髓后,用肝素处理过的微量采血管从颈部采血,3 000 r·min-1,4 ℃离心10 min,取上清液。取肝脏、肌肉、心脏、脑组织,立即放入液氮中,并转到-80 ℃低温冰箱贮存,用于之后渗透物质的检测。葡萄糖、乳酸、尿素、甘油的测定采用各自相应的试剂盒(南京建成生物工程研究所)。组织中渗透物质的含量用nmol·g-1 fresh tissue或μmol·g-1 fresh tissue表示,血浆中渗透物质的含量用μmol·L-1或μmol·mL-1表示。

1.6 统计分析所有数据用SPSS 16.0进行统计分析,在统计分析前进行正态性和方差同质性检验。用单因素方差分析(One-Way ANOVA)、LSD和Tamhane's T2多重分析比较实验结果的差异。所有描述性统计值用Mean±SE表示,显著水平设置为α=0.05。

2 结果 2.1 2种沙蜥生理学指标的比较通过比较2种沙蜥的生理学指标,发现荒漠沙蜥的体质量、吻肛长、尾长显著大于红尾沙蜥,但其体内的含水量明显低于红尾沙蜥(P=0.012;表 1)。

| 物种 Species |

体质量 Body mass/g |

吻肛长 Snout-vent length/cm |

尾长 Tail length/cm |

含水量 Body water content/% |

|

| 红尾沙蜥P. erythrurus | 5.906±0.207a | 5.43±0.10a | 5.48±0.09a | 71.76±0.74a | |

| 荒漠沙蜥P. przewalskii | 7.407±0.427b | 5.79±0.08b | 8.12±0.24b | 69.09±0.55b | |

| 注:不同字母表示2个物种之间的差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。 Note:Different letters indicate there is significant difference between 2 species (P<0.05). |

|||||

在干燥条件下,蜥蜴的过冷能力在2个物种间差异无统计学意义(P=0.584;图 1),过冷耐受温度红尾沙蜥为-6.35 ℃±0.33 ℃,荒漠沙蜥为-6.55 ℃± 0.13 ℃。

|

| 图 1 红尾沙蜥和荒漠沙蜥的过冷耐受温度 Fig. 1 The supercooling capacity of Phrynocephalus erythrurus and P.przewalskii |

| |

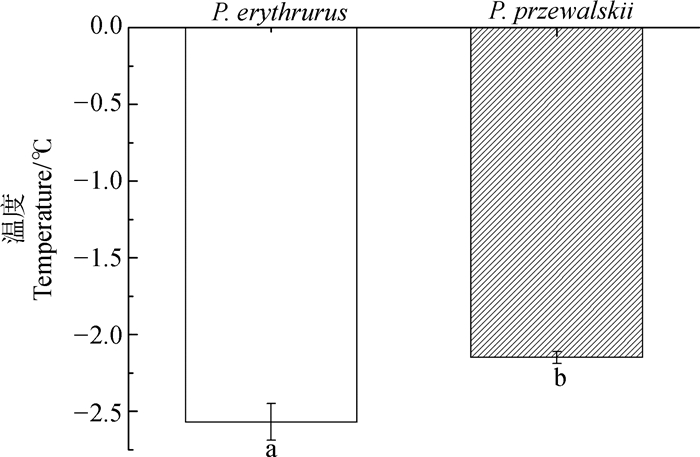

湿沙包围条件下蜥蜴对接种结冰耐受能力的结果显示,2个物种之间差异有统计学意义,而且红尾沙蜥的接种结冰温度显著低于荒漠沙蜥的(P=0.008;图 2),红尾沙蜥为-2.57 ℃±0.12 ℃,荒漠沙蜥为-2.15 ℃±0.04 ℃。

|

| 图 2 红尾沙蜥和荒漠沙蜥的接种结冰温度 Fig. 2 The ability to resist inoculative freezing of Phrynocephalus erythrurus and P. przewalskii 不同字母表示2个物种间差异有统计学意义(P<0.05);下图同。 Different letters indicate there is significant difference among 2 species (P < 0.05); the same below. |

| |

4 ℃条件下,红尾沙蜥的心率显著高于荒漠沙蜥的心率(P=0.003;图 3),同时,红尾沙蜥的呼吸频率要显著高于荒漠沙蜥(P<0.001;图 4)。

|

| 图 3 4 ℃条件下红尾沙蜥和荒漠沙蜥心率的比较 Fig. 3 The heart rate of Phrynocephalus erythrurus and P. przewalskii at 4 ℃ |

| |

|

| 图 4 4 ℃条件下红尾沙蜥和荒漠沙蜥呼吸频率的比较 Fig. 4 The breathing rate of Phrynocephalus erythrurus and P. przewalskii at 4 ℃ |

| |

研究发现,2个物种的血浆以及4个不同组织中的甘油、葡萄糖、乳酸、尿素4种渗透物质并没有呈现出有规律的差异(表 2)。

| 甘油/(nmol·g-1fresh tissue or μmol·L-1) | 葡萄糖/(μmol·g-1 fresh tissue or μmol·mL-1) | 乳酸/(μmol·g-1fresh tissue or μmol·mL-1) | 尿素/(μmol·g-1fresh tissue or μmol·mL-1) | ||||||||||||

| 红尾沙蜥P. erythrurus | 荒漠沙蜥P. przewalskii | P值 | 红尾沙蜥P. erythrurus | 荒漠沙蜥P. przewalskii | P值 | 红尾沙蜥P. erythrurus | 荒漠沙蜥P. przewalskii | P值 | 红尾沙蜥P. erythrurus | 荒漠沙蜥P. przewalskii | P值 | ||||

| 肝脏 | 2 543.50±203.17 | 1 504.50±121.82 | 0.001 | 35.47±2.17 | 43.74±3.81 | 0.080 | 31.76±2.52 | 46.35±1.84 | <0.001 | 107.05±2.61 | 101.17±7.65 | 0.479 | |||

| 肌肉 | 679.94±63.62 | 758.59±114.47 | 0.534 | 5.38±0.27 | 4.43±0.28 | 0.028 | 68.13±1.33 | 66.58±3.16 | 0.659 | 43.93±2.97 | 50.47±1.47 | 0.068 | |||

| 心脏 | 648.48±48.47 | 1 237.20±130.01 | 0.002 | 12.42±0.62 | 7.82±1.08 | 0.002 | 35.30±3.94 | 34.10±3.43 | 0.823 | 36.77±2.35 | 75.59±3.28 | <0.001 | |||

| 脑 | 1 103.80±139.11 | 270.02±82.76 | <0.001 | 5.29±0.28 | 6.32±0.42 | 0.060 | 37.80±2.55 | 29.32±1.52 | 0.013 | 34.04±1.53 | 27.96±1.01 | 0.005 | |||

| 血浆 | 59.36±6.72 | 49.63±5.48 | 0.284 | 14.75±0.79 | 11.96±0.34 | 0.060 | 8.67±0.96 | 16.83±0.92 | <0.001 | 2.33±0.20 | 2.14±0.21 | 0.519 | |||

变温动物几乎存在于地球上的每一个生态位,其体温与环境温度密切相关。由于一些特殊的适应性,它们也会分布在季节性或持续寒冷的高海拔或高纬度地区(Addo-Bediako et al., 2000)。经过高原环境长期的自然选择和适应,世居青藏高原的红尾沙蜥体内形成了多种可遗传的适应特性,与低海拔的荒漠沙蜥相比,其在线粒体、酶活性和基因水平上有独特的代谢调节策略(Tang et al., 2013)。本研究测定了不同海拔2种沙蜥的低温耐受性,初步探究红尾沙蜥适应高原低温环境的机制。

虽然避免结冰是许多动物采取的主要生存方式(Storey & Storey,1989;Duman,2001),但较深程度的过冷状态对动物造成损害。一是由于瞬间冰的形成(在成核作用下水迅速转化成冰),二是由于随后冰的迅速积累。例如,普通壁蜥只能耐受不多于体内5%水含量的结冰(Claussen et al., 1990)。本研究中,2种沙蜥都表现出较高的过冷耐受能力以及较易于接种结冰,同时,还发现干燥条件下结冰的蜥蜴全部死亡,湿沙包围条件下结冰的蜥蜴全部存活。这表明在较高温度下的接种结冰对这2种沙蜥是有益的,这有利于结冰过程的缓慢进行,而且通常能够提高存活率(Voituron et al., 2002)。红尾沙蜥的接种结冰温度要显著低于荒漠沙蜥,这可能是它适应生存环境的结果。

研究表明,体温可以很大程度上影响生物一系列的生理功能和行为表现(Bennett,1980;Kaufmann & Bennett,1989;Angilletta,2001)。本研究发现在4 ℃条件下,红尾沙蜥的心率和呼吸频率明显高于荒漠沙蜥,表明红尾沙蜥在低温条件下有更好的适应性。有研究表明,心率可以作为代谢率的指示指标(Currie et al., 2014;Zena et al., 2015),因此,我们认为将蜥蜴置于急性低温(4 ℃)条件下,红尾沙蜥的代谢率要高于荒漠沙蜥。

本研究并没有发现葡萄糖、尿素等可以作为抗冻保护剂存在的物质在2个物种间存在有规律的差异,这与在干燥条件下测定的2种蜥蜴的结冰温度没有差别一致。然而,在生物体内可能作为抗冻保护剂存在的渗透物质有许多种(如海藻糖、脯氨酸等),本实验只检测了其中4种,可能这2种沙蜥利用其他的渗透物质作为抗冻保护剂。许多结冰耐受的生物体在结冰之前积累抗冻物质,尤其是在季节性的变冷过程中(Storey & Storey,1988;Lee,2010)。有研究表明,初生锦龟Chrysemys picta冬季的血糖水平比秋季高15倍(Costanzo et al., 2008),而胎生蜥蜴至少高4倍(Grenot et al., 2000)。因此,2种沙蜥是否采用其他物质作为抗冻保护剂,以及那些能够作为抗冻保护剂存在的渗透物质在结冰前后是否有变化需进一步研究。

综上所述,2种沙蜥过冷能力的差异并没有统计学意义,但是红尾沙蜥对于接种结冰的耐受能力要显著高于荒漠沙蜥;同时,在面临相同的低温条件时,红尾沙蜥的表现优于荒漠沙蜥,表明其有更好的适应性。本研究并没有发现可以作为抗冻物质存在的4种小分子物质在2个物种之间存在有规律的差异,这可能是2个物种过冷能力没有差异的原因。

| Addo-Bediako A, Chown SL, Gaston KJ. 2000. Thermal tolerance, climatic variability and latitude[J]. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B:Biological Sciences, 267(1445): 739–745. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2000.1065 |

| Angilletta MJ. 2001. Thermal and physiological constraints on energy assimilation in a widespread lizard (Sceloporus undulatus)[J]. Ecology, 82(11): 3044–3056. DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[3044:TAPCOE]2.0.CO;2 |

| Bennett AF. 1980. The thermal dependence of lizard behaviour[J]. Animal Behaviour, 28: 752–762. DOI:10.1016/S0003-3472(80)80135-7 |

| Campbell JA, Solorzano A. 1992. The distribution, variation, and natural history of the middle American montane pitviper, Porthidium godmani[M]. Selva: Tyler, TX: 3-250. |

| Claussen DL, Townsley MD, Bausch RG. 1990. Supercooling and freeze-tolerance in the European wall lizard, Podarcis muralis, with a revisional history of the discovery of freeze-tolerance in vertebrates[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 160(2): 137–143. DOI:10.1007/BF00300945 |

| Cossins A. 2012. Temperature biology of animals[M]. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media: 2014-247. |

| Costanzo J, Grenot C, Lee Jr. RE. 1995. Supercooling, ice inoculation and freeze tolerance in the European common lizard, Lacerta vivipara[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 165(3): 238–244. |

| Costanzo JP, Lee RE, Ultsch GR. 2008. Physiological ecology of overwintering in hatchling turtles[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A:Ecological Genetics and Physiology, 309(6): 297–379. |

| Costanzo JP, Lee RE. 2013. Avoidance and tolerance of freezing in ectothermic vertebrates[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 216(11): 1961–1967. DOI:10.1242/jeb.070268 |

| Currie SE, Körtner G, Geiser F. 2014. Heart rate as a predictor of metabolic rate in heterothermic bats[J]. Journal of Experimental Biology, 217(9): 1519–1524. DOI:10.1242/jeb.098970 |

| Damme RV, Bauwens D, Castilla AM, et al. 1989. Altitudinal variation of the thermal biology and running performance in the lizard Podarcis tiliguerta[J]. Oecologia, 80(4): 516–524. DOI:10.1007/BF00380076 |

| Damme RV, Bauwens D, Verheyen RF. 1990. Evolutionary rigidity of thermal physiology:the case of the cool temperate lizard Lacerta vivipara[J]. Oikos, 57(1): 61–67. DOI:10.2307/3565737 |

| Duman JG. 2001. Antifreeze and ice nucleator proteins in terrestrial arthropods[J]. Annual Review of Physiology, 63(1): 327–357. DOI:10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.327 |

| Gaston KJ. 2003. The structure and dynamics of geographic ranges[M]. Demand: Oxford University Press: 27-52. |

| Graham J, Rubinoff I, Hecht M. 1971. Temperature physiology of the sea snake Pelamis platurus:an index of its colonization potential in the Atlantic Ocean[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 68(6): 1360–1363. DOI:10.1073/pnas.68.6.1360 |

| Grant BW, Dunham AE. 1990. Elevational covariation in environmental constraints and life histories of the desert lizard Sceloporus merriami[J]. Ecology, 71(5): 1765–1776. DOI:10.2307/1937584 |

| Grenot CJ, Garcin L, Dao J, et al. 2000. How does the European common lizard, Lacerta vivipara, survive the cold of winter?[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A:Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 127(1): 71–80. |

| Hahn DA, Denlinger DL. 2011. Energetics of insect diapause[J]. Annual Review of Entomology, 56: 103–121. DOI:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085436 |

| Huang SP, Hsu Y, Tu MC. 2006. Thermal tolerance and altitudinal distribution of two Sphenomorphus lizards in Taiwan[J]. Journal of Thermal Biology, 31(5): 378–385. DOI:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2005.11.032 |

| Humphries MM, Thomas DW, Speakman JR. 2002. Climate-mediated energetic constraints on the distribution of hibernating mammals[J]. Nature, 418(6895): 313–316. DOI:10.1038/nature00828 |

| Irwin JT, Lee Jr. RE. 2003. Cold winter microenvironments conserve energy and improve overwintering survival and potential fecundity of the goldenrod gall fly, Eurosta solidaginis[J]. Oikos, 100(1): 71–78. DOI:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.11738.x |

| Jin YT, Liu NF. 2010. Phylogeography of Phrynocephalus erythrurus from the Qiangtang Plateau of the Tibetan Plateau[J]. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 54(3): 933–940. DOI:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.11.003 |

| Kaufmann JS, Bennett AF. 1989. The effect of temperature and thermal acclimation on locomotor performance in Xantusia vigilis, the desert night lizard[J]. Physiological Zoology, 62(5): 1047–1058. DOI:10.1086/physzool.62.5.30156195 |

| Krebs CJ. 1974. The experimental analysis of distribution and abundance[M]//Krebs CJ. Ecology. Oxford, UK:Addison-Wesley:93-116. |

| Layne JR, Stapleton MG. 2009. Annual variation in glycerol mobilization and effect of freeze rigor on post-thaw locomotion in the freeze-tolerant frog Hyla versicolor[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 179(2): 215–221. DOI:10.1007/s00360-008-0304-6 |

| Lee RE. 2010. A primer on insect cold-tolerance[M]//Denlinger DL, LEE RE. Low temperature biology of insects. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press:3-34. |

| Navas CA. 2002. Herpetological diversity along Andean elevational gradients:links with physiological ecology and evolutionary physiology[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A:Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 133(3): 469–485. |

| Pough FH. 1980. The advantages of ectothermy for tetrapods[J]. American Naturalist, 115(1): 92–112. DOI:10.1086/283547 |

| Schiller TM, Costanzo JP, Lee RE. 2008. Urea production capacity in the wood frog (Rana sylvatica) varies with season and experimentally induced hyperuremia[J]. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part A:Ecological Genetics and Physiology, 309(8): 484–493. |

| Smith GR, Ballinger RE. 1994. Temperature relationships in the high-altitude viviparous lizard, Sceloporus jarrovi[J]. American Midland Naturalist, 131(1): 181–189. DOI:10.2307/2426621 |

| Sømme L. 1982. Supercooling and winter survival in terrestrial arthropods[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A:Physiology, 73(4): 519–543. DOI:10.1016/0300-9629(82)90260-2 |

| Storey K, Storey J. 1989. Freeze tolerance and freeze avoidance in ectotherms[M]//Wang LCH. Animal adaptation to cold. Berlin, Heidelberg:Springer:51-82. |

| Storey KB, Storey JM. 1988. Freeze tolerance in animals[J]. Physiological Reviews, 68(1): 27–84. |

| Storey KB. 2006. Reptile freeze tolerance:metabolism and gene expression[J]. Cryobiology, 52(1): 1–16. DOI:10.1016/j.cryobiol.2005.09.005 |

| Stuart L. 1951. The distributional implications of temperature tolerances and hemoglobin values in the toads Bufo marinus (Linnaeus) and Bufo bocourti Brocchi[J]. Copeia, 1951(3): 220–229. DOI:10.2307/1439101 |

| Tang X, Xin Y, Wang H, et al. 2013. Metabolic characteristics and response to high altitude in Phrynocephalus erythrurus (Lacertilia:Agamidae), a lizard dwell at altitudes higher than any other living lizards in the world[J]. PLoS ONE, 8(8): e71976. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0071976 |

| Voituron Y, Storey J, Grenot C, et al. 2002. Freezing survival, body ice content and blood composition of the freeze-tolerant European common lizard, Lacerta vivipara[J]. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 172(1): 71–76. DOI:10.1007/s003600100228 |

| Weigmann R. 1929. Die wirkung starker abkühlung auf amphibien und reptilien[J]. Zeitschrift für wissenschartliche Zoologie, 134: 641–692. |

| Zena LA, Gargaglioni LH, Bícego KC. 2015. Temperature effects on baroreflex control of heart rate in the toad, Rhinella schneideri[J]. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A:Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 179: 81–88. |

| Zhao EM, Adler K. 1993. Herpetology of China[M]. Oxford, Ohio, USA:Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles in Cooperation with Chinese Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles. |

| Zimmerman SL, Frisbie J, Goldstein DL, et al. 2007. Excretion and conservation of glycerol, and expression of aquaporins and glyceroporins, during cold acclimation in Cope's gray tree frog Hyla chrysoscelis[J]. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 292(1): R544–R555. |

2017, Vol. 36

2017, Vol. 36