扩展功能

文章信息

- 赫晨, 王建礼, 程广超

- HE Chen, WANG Jianli, CHENG Guangchao

- 可卡因对雌性棕色田鼠的运动性、社会行为及中枢精氨酸加压素、催产素和酪氨酸羟化酶表达的影响

- Effects of Cocaine on Locomotion, Social Behaviors and the Expression of Central Arginine Vasopressin, Oxytocin and Tyrosine Hydroxylase in Female Mandarin Voles

- 四川动物, 2016, 35(4): 488-495

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2016, 35(4): 488-495

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20160086

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2016-04-16

- 接受日期: 2016-06-08

可卡因是药物滥用者常用的成瘾性药物,能够影响多种神经递质系统,如增加大脑多巴胺(dopamine,DA)、5-羟色胺(5-hydroxytryptamine,5-HT)和去甲肾上腺素(norepinephrine,NE)等递质(Ritz et al.,1990;Kahlig & Galli,2003),这些递质系统反过来会影响行为以及涉及行为变化的激素,如雌激素、孕酮和催乳素(John et al.,1998;Nelson et al.,1998)。精氨酸加压素(arginine vasopressin,AVP)和催产素(oxytocin,OT)是2种重要的神经肽,主要由下丘脑室旁核(paraventricular nucleus,PVN)与视上核(supraoptic nucleus,SON)产生,涉及调节社会行为、攻击行为和情绪(Skuse & Gallagher,2009),尤其对调节单配制动物的行为具有重要作用(Ahern & Young,2009;Young et al.,2011)。此外,大量研究表明这2种神 经肽也参与药物奖赏和成瘾。例如,AVP参与调节可卡因戒断及可卡因诱导的条件位置偏爱(conditioned place preference,CPP)、运动性、自给药等行为敏感化(de Vry et al.,1988;Sarnyai et al.,1992a;Chui et al.,1998;Rodríguez-Borrero et al.,2010);OT能减少可卡因诱导的CPP、高运动性、刻板行为(stereotyped behavior)、自给药以及可卡因的复吸等(Sarnyai & Kovács,1994;Sarnyai et al.,2011;McGregor & Bowen,2012)。因此,AVP和OT系统是研究社会行为和药物滥用关系的重要枢纽(王建礼等,2011)。

社会行为及调控社会行为的神经化学物质与物种的婚配制度或社会组织有关(Razzoli et al.,2003)。物种的社会性水平会影响成瘾药物的敏感性(Cailhol & Mormede,1999;Curtis & Wang,2007)。因此,药物对神经肽及社会行为的影响可能具有种特异性和变异性。与实验大鼠和小鼠相比,棕色田鼠Lasiopodomysmandarinus在野外以家庭群维持社群生活,具有稳定的配偶联系(邰发道等,2001;邰发道,王廷正,2001;王建礼等,2005)和较复杂的社会行为,而且雌性较雄性表现出更多的攻击行为(翟培源等,2008;Wu et al.,2011)。酪氨酸羟化酶(tyrosine hydroxylase,TH)是DA合成的限速酶,可以标记DA神经元。先前的研究已发现可卡因能够对棕色田鼠形成奖赏效应(Wang et al.,2012)。在可卡因诱导棕色田鼠的行为变化中,AVP、OT和DA的作用还不清楚。本文通过对雌性棕色田鼠反复注射可卡因,检测其运动性、焦虑水平、社会行为以及AVP、OT和TH的变化,以期探讨可卡因对社会性动物的行为影响及内在机制。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料棕色田鼠种鼠捕自河南省灵宝市农作区(111°21′E,34°41′N,海拔650 m)。实验雌鼠为F3代鼠,塑料饲养笼(长0.4 m×宽0.28 m×高0.15 m)饲养,3~4只一笼。木屑做垫料,棉花做巢材,以胡萝卜为食。室温21 ℃±2 ℃,光照周期12L∶ 12D,食物、饮水充足。

1.2 行为实验 1.2.1 旷场行为实验分为2组。可卡因组(n=12),每天09∶ 00皮下注射20 mg·kg-1盐酸可卡因(青海制药厂,以生理盐水溶解),连续注射4 d,24 h后即第5天进行行为实验。对照组(n=10)每天注射等体积的生理盐水。旷场行为观察在旷场箱(长50 cm×宽50 cm×高25 cm)中进行。在旷场箱正上方1.5 m处安放4×60 W灯泡照明,使旷场箱中心光照强度达到400 lx。旷场箱被16等分,其中中间4等分为中央区域(central area),剩余12等分为周围区域(peripheral area)(Fiore & Ratti,2007)。行为观察开始时,被测棕色田鼠被置于旷场箱中央区域,使用数码摄像机拍摄5 min。每只棕色田鼠行为观察结束后,分别使用75%的酒精和蒸馏水对旷场箱进行清洗。拍摄完成后使用Noldus Observe 5.0(Noldus,Holland)分析棕色田鼠在中央区域停留时间和穿格次数。以中央区域停留时间占总时间的百分比评估焦虑样行为,穿格次数评估运动性。

1.2.2 社会互作旷场实验结束后进行社会互作实验。选择一日龄和体质量与被测雌鼠相似的雌性作为刺激鼠,刺激鼠以背部剪毛标记。观察箱(长44 cm×宽22 cm×高16 cm)底部覆以2 cm厚的木屑。测试时将实验鼠和刺激鼠分别置于观察箱两侧,中央用木板隔开,待适应3 min后取掉挡板,用数码摄像机拍摄15 min。实验结束后通过Noldus Observe 5.0分析以下行为的持续时间:

社会探究(social investigation):嗅闻身体的任何部位(包括肛殖区、面部及躯体)。

亲密行为(affiliative behavior):跨越身体、聚团和相互修饰等。

攻击行为(aggressive behavior):扑击、嘶咬、翻滚和追击等。

自饰行为(self-grooming behavior):用爪有节律地在口部、面部、耳部、腹下、侧肋、肛殖区等处挠动。

1.3 免疫组织化学染色实验鼠经腹腔注射戊巴比妥钠麻醉。先用4%多聚甲醛进行灌注固定;取出脑组织放入4%多聚甲醛后固定过夜(4 ℃),其后4 ℃下置于30%蔗糖溶液直至组织沉底。用冰冻切片机将脑作冠状切片,切片厚40 μm。用山羊血清封闭液在37 ℃湿盒内封闭1 h。滴加由抗体稀释液稀释的一抗:AVP(1∶ 2 000;AB1565,Upstate,Lake Placid,USA),OT(1∶ 2 000;AB911,Upstate,Lake Placid,USA)和TH(1∶ 1 500;ab112,Abcam,Hong Kong),4 ℃孵育72 h。0.01 M 磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS)漂洗5 min×4次。滴加生物素化羊抗兔IgG(博士德生物工程有限公司,武汉),37 ℃湿盒内孵育1.5 h。0.01 M PBS漂洗5 min×4次。滴加SABC试剂(博士德生物工程有限公司,武汉),37 ℃湿盒内孵育2.5 h。0.01 M PBS漂洗10 min×4次。DAB显色剂显色。常规酒精脱水,二甲苯透明,中性树胶封片。

各脑区参照《大鼠脑立体定位图谱》(包新民,舒斯云,1991)定位。每只鼠选择同一脑区的3张切片,利用显微测微尺在显微镜下计算相同面积内单侧脑区核团的免疫活性(immunoreactive,IR)神经元数量,包括下丘脑前区(anterior hypothalamus,AH)和PVN的AVP,PVN的OT以及中脑腹侧被盖区(ventral tegmental area,VTA)和PVN的TH。使用Olympus显微成像系统拍照。

1.4 统计分析所有数据用SPSS 13.0进行统计分析。独立样本t检验分析组间差异。数据结果以平均值±标准误(Mean±SE)表示,显著性水平为α=0.05。

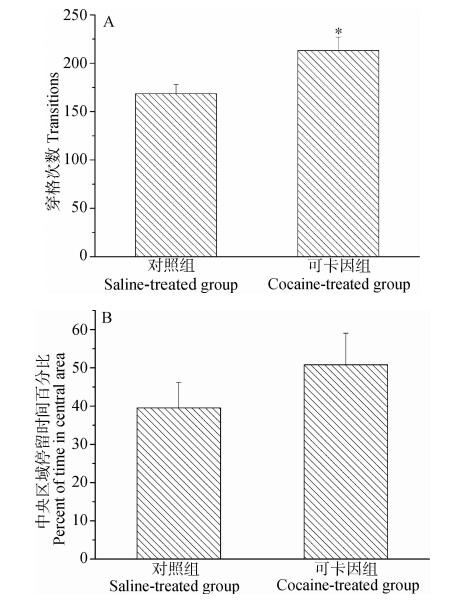

2 结果 2.1 旷场行为与对照组相比,可卡因组的穿格次数明显增加(t=2.451,P<0.05)(图 1:A),但在中央区域所占时间的百分比差异没有统计学意义(t=0.997,P>0.05)(图 1:B)。

|

| 图 1 生理盐水和可卡因处理后雌性棕色田鼠的旷场行为 Fig. 1 Behaviors of saline- and cocaine-treated female Lasiopodomys mandarinusin an open field test A. 穿格次数,B. 中央区域停留时间百分比; *对照组和可卡因组比较差异有统计学意义(P<0.05); 下同。 A. Number of transitions,B. The percent of time in the central area of the open field; * there is a significant difference between saline-treated group and cocaine-treated group(P<0.05); the same below. |

| |

与对照组相比,可卡因组的社会探究(t=-5.488,P<0.001)和攻击行为(t=-4.667,P<0.001)的持续时间减少,自饰行为的时间增多(t=2.354,P<0.05),但亲密行为之间差异没有统计学意义(t=0.117,P>0.05)(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 生理盐水和可卡因处理后雌性棕色田鼠的社会互作 Fig. 2 Social interaction in saline- and cocaine-treated female Lasiopodomys mandarinus |

| |

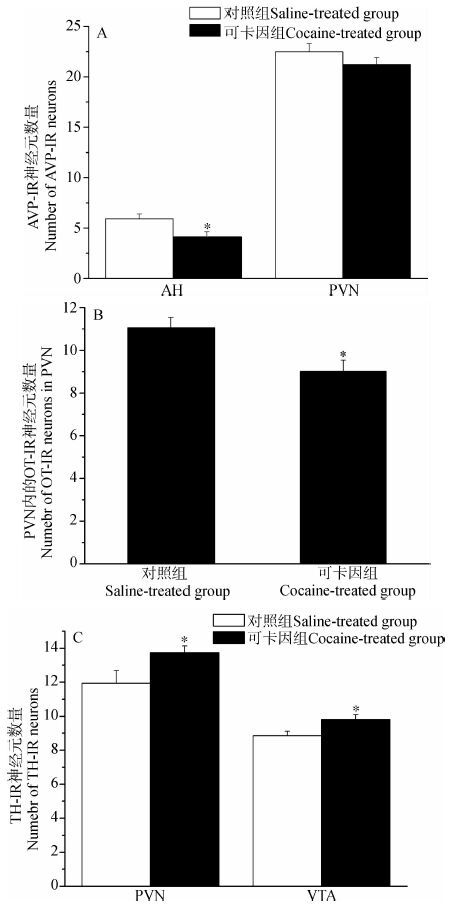

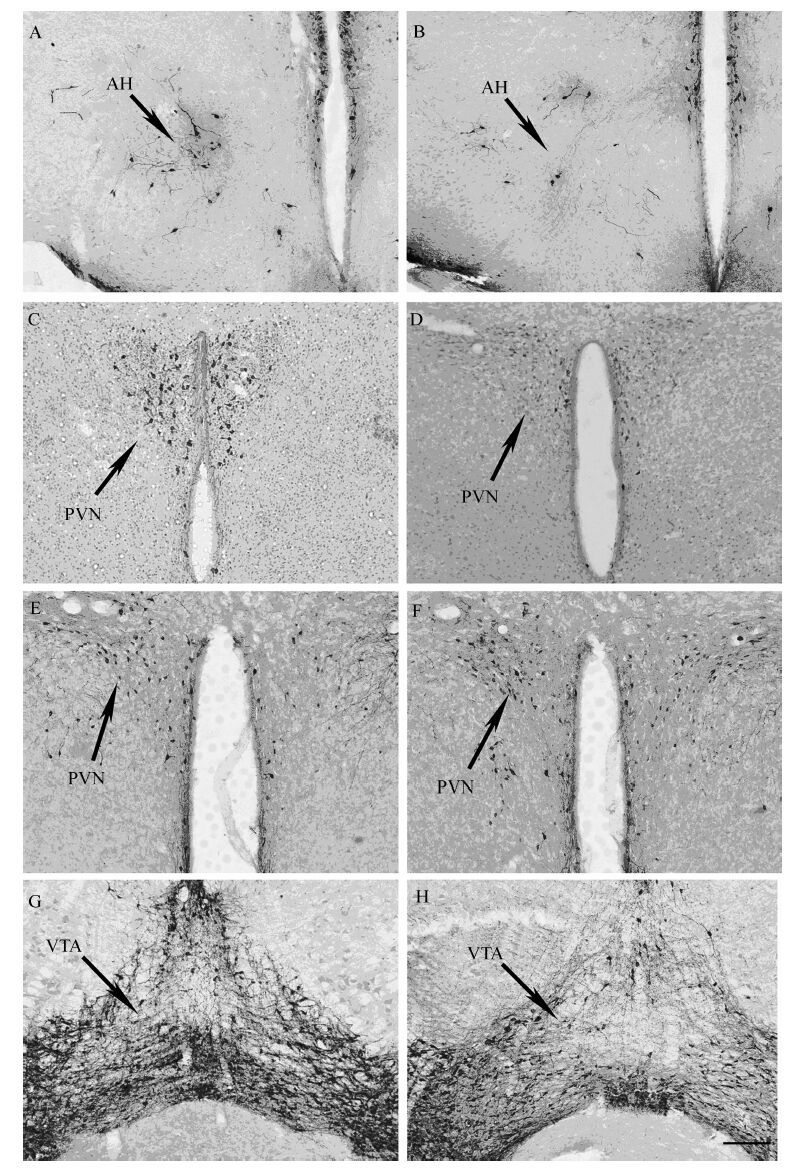

免疫组织化学染色结果表明,AH内AVP-IR神经元数量显著降低(t=2.549,P<0.05),但PVN内的AVP-IR神经元数量差异没有统计学意义(t=1.287,P>0.05)(图 3:A,图 4:A,B)。PVN内的OT-IR神经元数量显著减少(t=2.845,P<0.05)(图 3:B,图 4:C,D)。此外,在PVN(t=2.763,P<0.05)和VTA(t=2.453,P<0.05)内的TH-IR神经元数量显著增加(图 3:C,图 4:E~H)。

|

| 图 3 生理盐水和可卡因处理后雌性棕色田鼠 AVP-IR(A)、OT-IR(B)和TH-IR(C)神经元数目 Fig. 3 The number of AVP-(A),OT-(B)and TH-IR neurons(C) in saline- and cocaine-treated female Lasiopodomys mandarinus AH. 下丘脑前区,PVN. 下丘脑室旁核,VTA. 中脑腹侧被盖区。 AH. anterior hypothalamus,PVN. paraventricular nucleus,VTA. ventral tegmental area. |

| |

|

| 图 4 雌性棕色田鼠精氨酸加压素(A,B),催产素(C,D)和酪氨酸羟化酶(E,F,G,H)的免疫组织化学染色 Fig. 4 Arginine vasopressin(A,B),oxytocin(C,D)and tyrosine hydroxylase(E,F,G,H)immunopositive staining in femaleLasiopodomys mandarinus 对照组(A,C,E,G); 可卡因组(B,D,F,H); PVN. 下丘脑室旁核,AH. 下丘脑前区,VTA. 中脑腹侧被盖区; 比例尺=200 μm。 Saline-treated group(A,C,E,G); cocaine-treated group(B,D,F,H); PVN. paraventricular nucleus,AH. anterior hypothalamus,VTA. ventral tegmental area; Scale bars=200 μm. |

| |

本实验发现反复注射可卡因24 h后,与对照组相比,雌性棕色田鼠的运动性增强,但焦虑行为差异没有统计学意义。引起动物运动性增加是奖赏性药物的属性特征,也是行为敏感化的一种表现(Wise & Bozarth,1987)。许多研究证实可卡因显著地增加运动性(Johanson & Fischman,1989;Carey et al.,2005)。之前的研究也发现可卡因戒断24 h增加了大鼠(de Oliveira Citó et al.,2012)和C57BL/6J小鼠的运动性,但对BALB/cJ小鼠的运动性没有影响(Wang et al.,2014)。可卡因能诱导焦虑行为(Blanchard & Blanchard,1999;Paine et al.,2002)。本实验没有发现焦虑行为,有人对小鼠研究发现,可卡因戒断对焦虑水平没有影响(Niigaki et al.,2010;Stoker & Markou,2011)。但是通过高架十字迷宫研究发现,连续注射14 d可卡因,戒断4周后测试发现大鼠呈现持续的焦虑行为(El Hage et al.,2012)。结合本实验结果,暗示物种差异、药物注射的范式及戒断时间会影响焦虑水平。

社会互作包括许多行为成分,各成分具有不同的功能和神经化学环路(Varlinskaya & Spear,2008)。我们发现可卡因戒断减少了攻击行为和社会探究,这与一些研究结果相似(Sarnyai,1993;Lubin et al.,2001;Rademacher et al.,2002;Estelles et al.,2004)。反复注射可卡因,24 h后检测发现C57BL/6J小鼠的攻击行为减少,但对BALB/cJ小鼠没有影响(Wang et al.,2014)。Lubin等(2001)曾发现,雌性大鼠在连续注射30 mg·kg-1的可卡因后,攻击频次减少。也有研究报道药物的使用和戒断与攻击行为的变化没有相关性(Dhossche,1999;Estelles et al.,2004)。这些结果与物种、测量参数、攻击类型(保护性攻击、亲本攻击、社会性攻击)及药物剂量有关(Estelles et al.,2004)。自饰行为的变化能够反映情绪的变化(Summavielle et al.,2002;Carey et al.,2005),本实验中自饰行为增加可能与可卡因引起的情绪改变有关。

与对照组相比,可卡因降低了AH的AVP表达及PVN的OT表达,同时增加了PVN和VTA的TH表达。对动物而言,AVP系统主要调节雄性的社会行为,OT系统主要调节雌性的社会行为,也调节雄性的攻击行为,而雌性攻击行为的调节也不排除AVP的参与(Veenema & Neumann,2008)。在雄性的焦虑和攻击行为中,PVN的AVP具有重要的调节作用(Keverne & Curley,2004;Pan et al.,2009)。本实验中,PVN的AVP水平没有变化,这可能与焦虑水平没有改变有关。Sarnyai等(1992b)曾发现急性可卡因给药对下丘脑的AVP没有影响,但慢性处理会减少下丘脑的AVP。AH的AVP神经元是控制攻击行为的中心,AH内AVP的激活会易化攻击行为(Ferris et al.,1989;Gobrogge et al.,2007),相反,AH的AVP神经元的减少与攻击行为的减少有关(Ferris et al.,1989),因此,可卡因导致攻击行为的减少也与AH内AVP水平降低有关。此外,AVP并不影响可卡因诱导的运动能力(Sarnyai,1992a)。

Lubin等(2001)发现慢性可卡因注射导致处女大鼠攻击频次减少,海马体中OT 水平降低。产后雌鼠在急性或慢性注射可卡因后攻击行为改变,同时内侧视前区(medial preoptic area,MPOA)、杏仁核及PVN的OT降低(Elliott et al.,2001;Johns et al.,2010)。对去卵巢的雌性大鼠急性注射可卡因,海马体中OT的水平降低,但不影响杏仁核的水平(Johns et al.,1993)。说明可卡因对OT水平的影响与核区有关,并与体内雌激素水平有关。OT可以增加社会行为、减少焦虑(Keverne et al.,2004;Veenema & Neumann,2008)。OT对调节雌性之间的攻击行为尤其有效,例如,新生棕色田鼠幼仔注射OT,攻击行为会增加(Jia et al.,2008)。降低OT会减少雌性大鼠的拮抗行为(Razzoli et al.,2003)。因此,本实验中由于可卡因经历导致雌性攻击行为的下降也与OT下降有关。

可卡因成瘾效应主要通过抑制DA转运体,使其无法与DA正常结合,从而抑制DA的重摄取和转运,导致突触间隙DA浓度升高(Uhl et al.,2002;Kahlig & Galli,2003),DA能神经元持续兴奋,令使用者产生快感。许多动物实验研究表明,实现药物奖赏效应的神经结构主要是中脑-边缘-皮质DA系统(mesocorticolimbic dopamine system,MCLDS)(Insel,2003),在此系统中,VTA-伏核(nucleus accumbens,NAc)的神经通路尤其关键。DA能神经元的胞体主要位于VTA。NAc接受VTA的DA能传入纤维,激活DA功能,导致成瘾(Koob & Moal,1997;Ikemoto,2007)。因此,VTA是药物奖赏和成瘾的重要位点。中脑边缘系统的DA活动与可卡因诱导的行为和高运动性有关(Sarnyai,1993;Tran-Nguyen et al.,1998)。Ito等(2007)认为药物诱导的高运动性主要由中脑边缘DA系统调节,刻板行为主要由黑质纹状体(nigrostriatal)DA系统调节。VTA中TH表达的升高意味着DA合成和释放。已有研究发现TH与药物诱导的行为敏感化存在着密切关系,尼古丁或吗啡处理明显增加VTA或NAc的 TH表达(陈洪,高国栋,2003;李双成等,2010)。本实验中,VTA的DA能神经元通过增加TH的表达促进DA的合成,说明可卡因处理导致VTA-NAc通路的DA活动增强,这可能是导致运动性升高的一个原因。而且高水平DA与直立行为增加有关(Summavielle et al.,2002)。中脑边缘系统的DA也是OT调节的潜在下游位点(Shahrokh et al.,2010),也不排除OT通过影响DA传递调节可卡因诱导的行为效应(Sarnyai & Kovàcs,1994;Sarnyai,1999),如OT能够干扰DA对运动性增强的效应(Kovàcs et al.,1990)。

PVN的TH是儿茶酚胺的限速酶,它标记的神经元还包括NE(Liposits et al.,1986;Babovic et al.,2004)。由于NE在PVN的活动中具有突出作用,PVN的TH升高更多地与NE释放有关(Zhang et al.,2010;Flak et al.,2014)。研究发现前额叶皮质(prefrontal cortex,PFC)的NE具有调节攻击行为的作用(Cambon et al.,2010),VTA的TH也参与攻击行为(Filipenko et al.,2001)。因此,本研究不能排除可卡因导致的攻击减少与PVN和VTA的TH变化有关。

总之,反复暴露于可卡因会诱导雌性棕色田鼠行为敏感化并改变其社会行为。AVP、OT和TH的变化对调节这些行为具有重要作用。大量临床和预临床研究已证实药物成瘾具有性别差异,雌性比雄性对成瘾药物更敏感,例如,雌性大鼠习得可卡因自给药的时间和形成CPP的时间更短,并表现出更强的行为敏感化(Anker & Carroll,2011)。当前,药物滥用者中的女性比例正在增加(US.Department of Health and Human Services,2013),因此,研究雌性成瘾行为及机制对于制定针对女性药物滥用者的治疗策略具有重要的参考价值。

2016, Vol. 35

2016, Vol. 35