扩展功能

文章信息

- 王承东, 杨波, 黄杰, 黄炎, 成彦曦, 李仁贵, 黄山, 李德生, 张和民

- WANG Chengdong, YANG Bo, HUANG Jie, HUANG Yan, CHENG Yanxi, LI Rengui, HUANG Shan, LI Desheng, ZHANG Hemin

- 大熊猫粪便野外暴露时间对微卫星实验的影响

- Effect of Exposure Time of Ailuropoda melanoleuca Feces on Microsatellites Analysis

- 四川动物, 2016, 35(4): 481-487

- Sichuan Journal of Zoology, 2016, 35(4): 481-487

- 10.11984/j.issn.1000-7083.20160033

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2016-02-16

- 接受日期: 2016-03-24

2. 四川省濒危野生动物保护生物学重点实验室, 四川大学生命科学学院, 成都 610064;

3. 河南商丘师范学院生命科学学院, 河南商丘 476000

2. Sichuan Key Laboratory of Conservation Biology on Endangered Wildlife, College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610064, China;

3. College of Life Sciences, Shangqiu Normal University, Shangqiu, Henan Province 476000, China

20世纪90年代中期出现的野生动物非损伤性取样已得到广泛应用(Taberlet et al.,1999;陈璐,岳曦,2007;Roques et al.,2014;Sugimoto et al.,2014)。在所有非损伤性取样中,粪便最易收集,且对动物的干扰及负面影响最小,因此是非损伤性取样中最具 有潜在价值的研究材料(魏辅文等,2001;Zhan et al., 2006;Zhu et al.,2013)。在野生动物的物种鉴定(Roques et al.,2014)、个体识别(Taberlet & Luikart,1999;Chakraborty et al.,2014)、性别鉴定(Baumgardt et al.,2013;Roques et al.,2014)、交配方式分析(Caniglia et al.,2014)、种群遗传结构分析(Caniglia et al.,2014)、遗传多样性评估(Sugimoto et al.,2014)、基因流分析(Saarinen et al.,2014)、种群数量及保护管理单元的制定(方盛国等,1996)等方面已得到广泛应用。

粪便暴露在野外环境中,DNA会因被核酸内切酶作用而降解,DNA降解随着暴露时间的延长而增加,影响PCR的扩增甚至不能扩增(Frantzen et al.,1998)。虽然有研究表明,在野外暴露12 h甚至1 d的粪便样品能够获得很好的实验结果(Murphy et al.,2002;Chambers et al.,2004;Nsubuga et al.,2004),但DNA的降解受到多种因素的影响,如温度、湿度、光照强度等(Femando et al.,2003)。大熊猫Ailuropoda melanoleuca野生个体数量稀少,在野外生活十分警觉,遇见率极低,野外样品的采集对粪便的依赖度更高,而且在野生环境中很难获得新鲜粪便。因此,较准确地辨别大熊猫粪便暴露时间和确定暴露多久的粪便能够用于进一步的分子生物学研究对于大熊猫野外种群数量调查(方盛国等,1996)、种群遗传学(Lu et al.,2001;Zhang et al.,2007;Shen et al.,2009;Yang et al.,2011;Zhu et al.,2011;Huang et al.,2015)以及野化放归(杨波等,2013)等生态学问题的研究具有重要意义。本研究旨在探讨不同新鲜程度粪便样品的DNA提取质量与后续分子实验的效果,为野外工作提供参考。

1 材料和方法 1.1 样品采集与处理2013年1月采集中国保护大熊猫研究中心卧龙核桃坪野化基地3只圈养大熊猫的粪便样品,每只大熊猫采集2团粪便,做2个环境处理。仿野外 环境:将粪便置于四川大学生命科学学院楼外草丛中(温度9.97 ℃±3.16 ℃,湿度48.27%±16.38%);恒定环境:室内恒温箱温度22.5 ℃±0.5 ℃,湿度62.5%±2.5%。每周1次采样并提取DNA,利用10个微卫星标记进行分析。

2013年6月获取中国保护大熊猫研究中心雅安碧峰峡基地的大熊猫粪便样品共24份,编号为YA01~YA24。样品均置于人工竹林中,竹密度为每平方米31株,平均竹高1.5 m,竹盖度92%,温度21.4 ℃±2.0 ℃,湿度80.8%±10.7%,暴露不同时间用于取样检测。

2014年8月采集中国保护大熊猫研究中心卧龙核桃坪野化基地4只半野化大熊猫的粪便样品,做4个环境处理。

A. 竹林地:竹密度为每平方米27株,竹盖度95.5%,基质为腐竹叶和枯竹秆混合的松软泥土,郁闭度0.92,25°左右的半阴阳坡,温度16.6 ℃±2.9 ℃,湿度77.2%±28.3%。

B. 苔藓地:竹密度为每平方米12株,竹盖度90%,基质为潮湿的苔藓地,郁闭度0.85,2°左右的半阴阳坡,为竹林边缘地带,类似大熊猫过道的生境类型,温度16.8 ℃±3.0 ℃,湿度77.7%±28.0%。

C. 卧息地:高大乔木底部,基质为覆盖有枯枝叶的硬质泥地,郁闭度0.90,18°左右的半阴阳坡,温度17.2 ℃±2.8 ℃,湿度80.0%±30.0%。

D. 卧穴口:位于岩石底部内凹处,基质为碎石,郁闭度0.78,10°左右的阴坡,温度17.3 ℃±2.8 ℃,湿度76.0%±27.0%。

2015年9月下旬采集中国保护大熊猫研究中心都江堰基地的圈养大熊猫粪便样品,做2个环境处理。

E. 草地:竹盖度约95%,松软泥土,上盖腐竹叶,并夹生草本植物,阴凉潮湿;温度19.5 ℃±3.5 ℃,湿度64.5%±6.8%。

F. 裸露地:完全暴露在阳光下的碎石地,相对干燥,东南面有一建筑,距离约1 m;温度20.0 ℃±2.9 ℃,湿度61.9%±3.9%。

粪便新鲜程度共设计6个时间梯度,即1 d、3 d、7 d、14 d、21 d和28 d。

1.2 粪便DNA提取大熊猫粪便样品DNA提取使用德国Qiagen生产的试剂盒QIAamp DNA Stool Kit,步骤及方法按厂商使用说明操作,琼脂糖凝胶电泳初步检测DNA提取是否成功、DNA浓度及质量,-20 ℃保存。

1.3 微卫星位点选择Huang等(2015)基于大熊猫基因组微卫星筛选了能够有效使用的大熊猫粪便DNA的微卫星位点。本文使用了其中10个微卫星位点,并对每1个微卫星位点的上游引物F’端进行荧光标记。

1.4 PCR反应条件及基因分型25 μL PCR反应体系:25 ng DNA,2.5 μL 10×PCR buffer,1.0~2.0 μm MgCl2,200 μM dNTP,上、下游引物各1.0 μm,1 U Taq酶,ddH2O补足至25 μL。

PCR反应程序:95 ℃ 4 min;95 ℃ 30 s,60 ℃ 50 s,72 ℃ 50 s,35个循环;72 ℃延伸10 min。PCR反应在iCycler PCR反应仪(Bio-Rad,USA)中进行,PCR产物4 ℃避光保存,每个样本PCR产物取5 μL,用1%琼脂糖电泳检测每个样本是否成功扩增,确定获得产物为单一、大小正确的DNA片段。各个样本PCR产物使用377 DNA sequencer(ABI PRISM,USA)进行基因分型,使用GeneMapper v3.2确定样本等位基因数,等位基因大小相对于分子内标ROX-500 决定。基因分型由北京阅微基因公司完成。

1.5 数据分析每个DNA样本做3个PCR重复试验和3次重复分型,成功分型的位点数以3次数据的平均值(x)表示。基因分型数据结果用Micro-checker(Oosterhout et al.,2004)分析,个体识别用Microsatellite tools(Park,2001)计算。利用SPSS 22.0作数据分析。

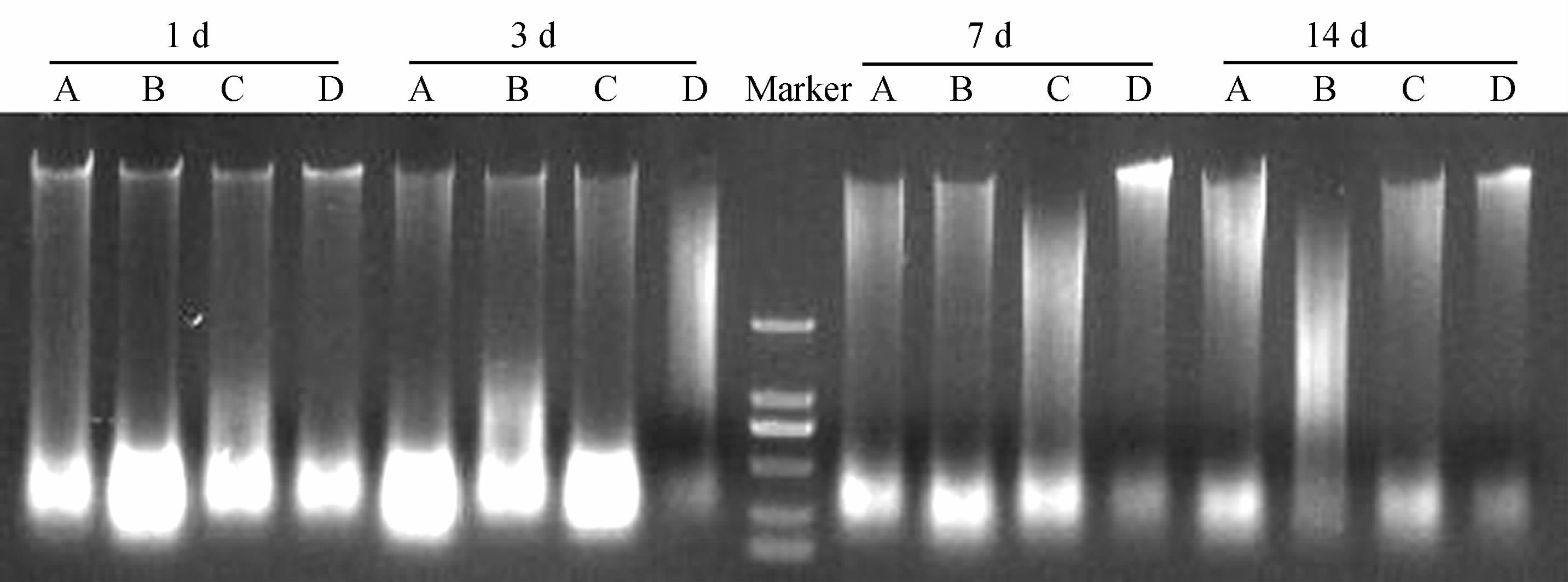

2 结果 2.1 DNA提取质量粪便样品暴露时间的不同,所提取的DNA质量存在差异。2013年1月放置于四川大学生命科学学院楼外草丛中的粪便样品暴露不同时间后,提取DNA 电泳检测发现,14 d以内均能获得较高质量的DNA(图 1)。2013年6月放置于雅安碧峰峡基地人工竹林中的粪便样品,暴露7 d后已有一些降解,但仍有部分样品能够提取较高质量的DNA(编号为13~15),而暴露了18 d(编号为16~19)和30 d的样品(编号为20~24)提取的DNA质量较差,降解严重(图 2)。2014年8月放置于卧龙核桃坪野化基地野生环境下的样品(图 3),3 d内均能提取质量较好的DNA,从7 d后开始出现不同程度的降解;而卧穴口的粪便即使暴露14 d后,其DNA质量仍然较好。2015年9月下旬放置于都江堰基地模拟野生环境下的样品,暴露21 d后还可以提取出较好质量的DNA(图 4)。表明不同环境下,粪便样品DNA的保存时间差异较大。

|

| 图 1 2013年1月放置于四川大学生命科学学院楼外的大熊猫粪便样品DNA提取质量 Fig. 1 DNA extracted from Ailuropoda melanoleuca feces exposed outside the building of College of Life Sciences, Sichuan University,January 2013 |

| |

|

| 图 2 2013年6月放置于中国保护大熊猫研究中心雅安碧峰峡基地大熊猫粪便样品DNA提取质量 Fig. 2 DNA extracted fromAiluropoda melanoleucafeces exposed in the field of Ya’an Bifeng Gorge Base, China Conservation and Research Center for Giant Panda,Sichuan,June 2013 |

| |

|

| 图 3 2014年8月放置于中国保护大熊猫研究中心卧龙核桃坪野化基地大熊猫粪便样品DNA提取质量 Fig. 3 DNA extracted from Ailuropoda melanoleuca feces exposed in the field of Wolong Base, China Conservation and Research Center for Giant Panda,Sichuan,August 2014 A.竹林地 bamboo forest,B.苔藓地 moss,C.卧息地 bed site,D.卧穴口 entrance of cave; 下同,the same below. |

| |

|

| 图 4 2015年9月放置于中国保护大熊猫研究中心都江堰基地大熊猫粪便样品DNA提取质量 Fig. 4 DNA extracted from Ailuropoda melanoleuca feces that exposed in the field of Dujiangyan Disease Control Center,China Conservation and Research Center for Giant Panda,Sichuan,September 2015 E.草地 grassland,F.裸露地 open ground; 下同,the same below. |

| |

利用10个微卫星位点对不同暴露时间粪便样品的DNA进行了PCR扩增及基因分型。每个样品3次重复,结果无差异,同环境、同暴露时间样品间的分析结果差异无统计学意义(P>0.05)。不同环境中的样品分析结果存在一定差异,即样品DNA的PCR扩增成功率均随着暴露时间的增加而降低。样品暴露35 d后,环境导致的差异有统计学意义(P<0.05)。置于恒温(22.5 ℃±0.5 ℃)、恒湿(62.5%±2.5%)的环境条件下,暴露 35 d后,选取的10个位点中有6个以上的位点 能成功分型;而置于室外环 境条件下(温度9.97 ℃±3.16 ℃),由于温度较低,

暴露42 d后样品中的10个位点中仍有6个以上的位点能成功分型(表 1)。

| 暴露天数 Exposure days | S1分型成功的平均位点数 The mean number of successfully genotyped loci in S1 | S2分型成功的平均位点数 The mean number of successfully genotyped loci in S2 | S3分型成功的平均位点数 The mean number of successfully genotyped loci in S3 | P值 P-value | |||

| In | Out | In | Out | In | Out | ||

| 1 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 0.609 |

| 3 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 0.638 |

| 7 | 9.7 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 0.539 |

| 14 | 9.3 | 9.0 | 8.7 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 8.3 | 0.265 |

| 21 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 8.7 | 8.7 | 0.961 |

| 28 | 7.3 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 0.265 |

| 35 | 6.3 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 0.032* |

| 42 | 6.0 | 8.0 | 5.7 | 6.3 | 5.3 | 7.3 | 0.003** |

| 49 | 5.0 | 6.3 | 4.3 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 5.6 | 0.007** |

| 56 | 4.0 | 6.3 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 5.7 | 0.007** |

| 63 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.0 | 4.0 | 0.028* |

| 注 Notes: *P<0.05,**P<0.01; In. 恒温恒湿环境constant temperature and humidity environment,Out. 室外环境outdoor environment; 下表同,the same below. | |||||||

根据Huang等(2015)建立的个体识别系统,15个微卫星位点中,使用6个位点能够成功进行大熊猫的个体识别和亲子鉴定。放置于中国保护大熊猫研究中心雅安碧峰峡基地模拟野化环境中的粪便样品,基因分型结果显示,暴露18 d内的样品平均有6个以上的位点能成功分型,能够用于个体识别研究。而超过18 d的样品,DNA降解较为严重,给基因分型带来一定的难度,而超过30 d的样品,分型成功率仅为45%,不能满足个体识别及亲子鉴定的要求(表 2)。

| 暴露天数 Exposure days | 各样品成功分型的平均位点数 The mean number of successfully genotyped loci in each sample | x | |||||

| No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 4 | No. 5 | No. 6 | ||

| 3 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.3 | 10.0 | 9.7 |

| 4 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.3 | 9.7 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.5 |

| 7 | 9.3 | 8.7 | 9.3 | — | — | — | 9.1 |

| 18 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 8.0 | 6.3 | — | — | 7.0** |

| 30 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 5.7 | 3.3 | 3.7 | — | 4.5** |

2014年8月放置于中国保护大熊猫研究中心卧龙核桃坪野化基地野外环境中的粪便样品暴露7 d后,微卫星分型成功率出现明显下降,苔藓地样品的分型成功率只有50%左右,不能用于后续分析。不管怎样,卧穴口样品的DNA保存较好,暴露21 d后仍有大约60%的位点可以成功分型。2015年9月放置于中国保护大熊猫研究中心都江堰基地的样品暴露7 d后DNA保存较好,约有60%以上的位点可以成功分型,暴露14 d时,草地样品的DNA降解严重,成功分型的位点降至一半以下,而裸露地样品的位点仍有60%以上能够成功分型,可以进行后续分析(表 3)。

| 暴露天数 Exposure days | 卧龙样品成功分型的平均位点数 The mean number of successfully genotyped loci in Wolong Base | P值 P-value | 都江堰样品成功分型的平均位点数 The mean number of successfully genotyped loci in Dujiangyan Disease Control Center | P值 P-value | ||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | |||

| 1 | 10.0 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 0.748 | — | — | — |

| 3 | 9.3 | 8.0 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 0.103 | 7.6 | 8.3 | 0.197 |

| 7 | 7.7 | 5.7 | 6.0 | 7.3 | 0.104 | 6.3 | 7.3 | 0.099 |

| 14 | 6.3 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 7.0 | 0.018* | 4.6 | 6.6 | 0.043* |

| 21 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 1.0 | 6.0 | 0.021* | 3.3 | 5.0 | 0.072 |

| 28 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 0.3 | 4.3 | 0.023* | 1.3 | 2.3 | 0.099 |

本研究旨在探讨大熊猫粪便暴露时间与DNA提取质量以及后续分子生物学研究的关系,进而对野外粪便采集提供参考。本研究于2012年12月—2013年1月,在四川大学校园内模拟野外环境暴露粪便样品,发现冬季寒冷干燥的环境最适于粪便的保存,即使暴露时间长达42 d,依然可以获得较高质量的DNA。但是,2013年6月在更接近野外环境的中国保护大熊猫研究中心雅安碧峰峡基地的人工竹林中,暴露18 d的样品降解严重,这可能由于研究期处于初夏,正是多雨时节,温、湿度高,粪便DNA降解速度快。2014年8月在有野生大熊猫分布的中国保护大熊猫研究中心卧龙核桃坪野化基地的野外环境中,暴露7 d的粪便样品DNA降解就较为严重,8月气温更高,相关酶活性也更高,DNA降解更快。因此不同季节,粪便样品中DNA的保存时间差异显著,建议野外粪便样品的采集尽可能选择在气温较低、少雨的秋、冬季进行。 粪便DNA降解严重与否,除与气温和天气有关外,与粪便暴露的环境也有一定的关系。野外环境中的植被类型、郁闭度、灌木盖度、坡度和坡向等因子直接影响环境中的温度和湿度,因而与粪便中DNA的保存时间必然相关。先前研究表明,四川野生大熊猫常出现在郁闭度大于0.50的落叶阔叶林和针阔混交林中,微生境为竹林,其多选择平均高度为2~5 m、盖度大于50%的竹林中觅食,喜欢在平缓的(坡度在6~30°范围内)东南坡向或阳坡与半阳坡的生境中活动,在海拔2 000~3 000 m的活动较多(魏辅文,冯祚建,1999;张泽钧,胡锦矗,2000;康东伟等,2011;赵秀娟等,2012)。本研究中卧龙的试验样地符合大熊猫日常活动的生境。研究表明暴露7 d的粪便样品中的DNA约有一半以上的微卫星位点能够成功分型,且微生境较干燥的环境,比如卧穴口粪便样品中的DNA保存时间更长,暴露14 d以内的粪便可以满足微卫星分析要求,甚至暴露21 d的粪便也可以分析。这些结果可以为野外粪便的收集提供参考。

4 粪便样品采集建议在野外粪便样品采集时,需要根据样品的外形特点,如粪便表皮黏膜组织的干燥程度、黏膜的光泽度、黏膜厚度,判断粪便样品暴露的大致时间。据野外观察,在3 d以内排出的大熊猫粪便很容易辨认,粪便表面的黏液完整,有光泽,触摸有光滑细腻的感觉,打开即能嗅到一股清香的竹味,表面颜色与里面相同,成色新鲜,粪团表面无霉菌滋生(郭建,胡锦矗,2001)。暴露7 d的粪便在湿热的微环境下,其表面无黏膜,有少量白色菌丝,粪便稍松散;而在较干燥的环境下,其表面有一层犹如薄纸状的略带光泽的黏膜,无菌丝滋生,外形保持完整。暴露14 d的粪便松散,表面霉菌明显增多,菌丝长度在1 cm左右,有霉味;较干燥环境下的粪便与暴露7 d时的几乎无变化。暴露21 d的粪便外形松散严重,霉味严重,霉菌布满粪便表面,菌丝最长长度在2 cm左右;较干燥的环境下,粪便干裂,表面无薄纸状黏膜或极少。

基于本研究结果,我们对野外大熊猫粪便的采集有以下建议:(1)野外粪便采集尽量选择在秋、冬季开展,粪便暴露时间最好不超过14 d,如果需要在春、夏季采样,则粪便暴露时间最好不超过7 d。(2)野外粪便采集时,尽量选择干燥、透气微生境中的粪便,因为干燥、透气环境中粪便DNA保存时间较长。(3)采集时记录清晰、详尽,并注意重复采样,以便后续研究。

2016, Vol. 35

2016, Vol. 35