文章信息

- 龚杰, 耿圆圆, 张舒, 刘伟, 吴伟伟, 李若瑜, 张建中.

- Gong Jie, Geng Yuanyuan, Zhang Shu, Liu Wei, Wu Weiwei, Li Ruoyu, Zhang Jianzhong

- 我国病原真菌相关的公共卫生风险浅析

- Analysis of public health risks associated with pathogenic fungi in China

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(12): 1977-1983

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(12): 1977-1983

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230615-00376

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-06-15

2. 北京大学第一医院皮肤性病科/国家皮肤与免疫疾病临床医学研究中心/北京大学真菌和真菌病研究中心/皮肤病分子诊断北京市重点实验室/北京大学第一医院-中国疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所病原真菌联合实验室, 北京 100034;

3. 海南省第五人民医院整形与皮肤外科, 海口 570102

2. Department of Dermatology, Peking University First Hospital/National Clinical Research Center for Skin and Immune Diseases/Research Center for Medical Mycology, Peking University/Beijing Key Laboratory of Molecular Diagnosis on Dermatoses/Peking University First Hospital-National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention Joint Laboratory of Pathogenic Fungi, Beijing 100034, China;

3. Derpartment of Plastic and Dermatologic Surgery, the Fifth People's Hospital of Hainan Province, Haikou 570102, China

相比于病毒和细菌,多数真菌的致病力总体偏弱。除少数高致病性真菌以外,严重的真菌感染主要以机会性感染的形式发生于免疫受损人群[1]。因此,病原真菌长期以来并未得到公共卫生体系的重视。但近年来“超级真菌”耳念珠菌的全球扩散、印度的群体性毛霉感染,均提示我国病原真菌相关的公共卫生风险需要得到全面而系统的关注。

目前一般认为真菌界的物种总数约200万~500万,约12万个物种已被准确描述[2-3]。其中约200余个物种可明确导致人类感染[4]。能感染人类的病原真菌通常需要满足4个标准[5-6]:①能耐高温,即能在≥37 ℃的环境中生长;②能侵入人体,即能穿透或绕过人体屏障,到达寄生的组织部位;③能溶解并吸收人体的组织,以摄取营养;④能有效抵御人体免疫系统。

目前为止,并未发现病原真菌的致病力和系统发育之间存在清晰的对应关系。例如,烟曲霉是常见致病菌,但与之亲缘关系最近的Aspergillus oerlinghausenensis和Aspergillus fischeri,却不属于致病菌[7];白念珠菌是常见致病菌,但与之亲缘关系最近的都柏林念珠菌感染在临床却相对罕见[8-9]。因此,评估某一种病原真菌相关的公共卫生风险,仍需要以临床感染的真实病例为主,很难仅凭物种分类或基因组特征等信息进行预测。换言之,目前无法基于某一个病原真菌的系统分类地位或基因组特征预测其致病特性。

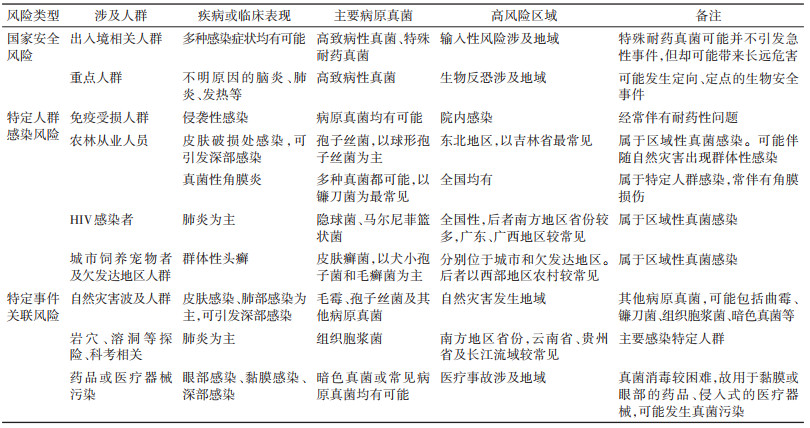

国内病原真菌相关的公共卫生风险主要体现在国家安全风险、特定人群感染风险和特定事件关联风险方面,同一种病原真菌可能会在不同场合引起不同类型的风险。见表 1。

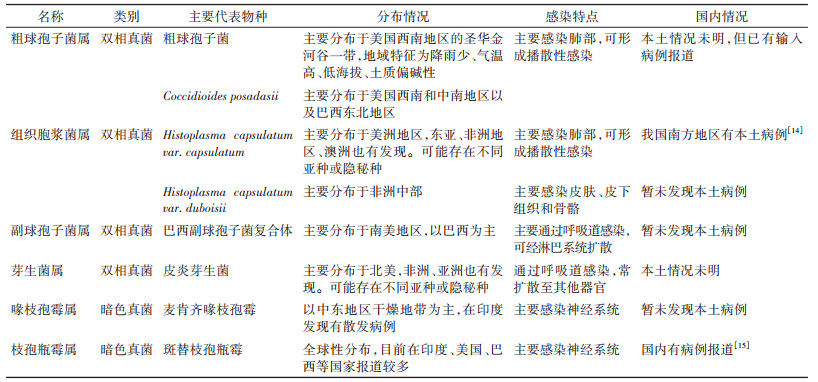

1. 高致病性真菌:现行《人间传染的病原微生物名录》(2006版)中,属于生物安全3级(BSL-3级)的病原真菌共4个:粗球孢子菌、荚膜组织胞浆菌、马皮疽组织胞浆菌、巴西副球孢子菌[10]。此外,麦肯齐喙枝孢霉、斑替氏枝孢瓶霉和皮炎芽生菌虽然国内被归于生物安全2级(或未明确规定),但在国际上一般认为是BSL-3级。

由于分类学的进步,部分物种在种水平可能会出现一些调整。如基于基因组学研究早期被认为荚膜组织胞浆菌的部分进化分枝,近年又被定义新物种Histoplasma mississippiense、Histoplasma ohiense、Histoplasma suramericanum[11]。同时,考虑到可能还会发现存在新的亚种、变种或隐秘种。例如,发现芽生菌属也许还存在一个隐秘种Blastomyces gilchristii[12],而副球孢子菌属可能早期被定义为巴西副球孢子菌复合体的一个进化分枝的“Pb01-like”,近年来被定义为另一个新种Paracoccidioides lutzii[13]。由于高致病性真菌工作需要在BSL-3级实验室里开展,很多病原真菌实验室无条件开展相关工作。目前相关的物种分类研究有限,很多细节有待进一步确认。因此,部分高致病性真菌可能需要以属水平进行管理。见表 2。

依据生理特征,高致病性真菌主要涉及双相真菌和暗色真菌。其中,双相真菌指真菌在不同的生长环境可以呈现为不同的菌相——酵母或菌丝。常见的影响因素为温度,在自然环境(约20~25 ℃)中,菌株形态为菌丝;而在宿主体内(37 ℃),菌株形态为酵母[16]。这种菌相变化的能力,使双相真菌常具有更强的致病力[17-18]。暗色真菌,也被称为黑酵母,但暗色真菌也包括一部分丝状真菌[19-20]。暗色真菌能产生黑色素,可能在一定程度上影响其致病特性。部分暗色真菌能感染神经系统(如斑替枝孢瓶霉和麦肯齐喙枝孢霉),因此也被认为具有较高的风险。

高致病性真菌的地域分布总体比较清晰。我国组织胞浆菌和斑替枝孢瓶霉有本土病例报道(表 2)[14-15],其他病例为输入性病例。需要特别指出的是,我国某些球孢子菌病的病例中,> 40%感染原因并不确定[21]。球孢子菌属物种的准确分布,仍需要进一步的研究。

由于缺乏系统性监测,国内高致病性真菌的公共卫生风险只能基于一些侧面的证据进行推测。例如,早期基于组织胞浆菌素皮试实验的抽样调查认为,我国湖南、江苏、四川等省份人群中均有较高的阳性比例(8.9%~21.7%)[22-24]。但我国报道的组织胞浆菌病例总体并不多,这可能与诊断能力不足有关。因此,包括组织胞浆菌在内的高致病性真菌,在我国的真实分布和感染情况急需加强监测。此外,有国外旅行(居)史的人群感染高致病性真菌的风险也需要得到关注。

2. 特殊耐药真菌:目前临床抗真菌药物的种类相对有限,主要包括唑类、多烯类、棘白菌素类和嘧啶类[25],均已经发现耐药现象[26],而且,在耳念珠菌中,发现了能对所有抗真菌药物耐药的泛耐药菌株[27]。

真菌耐药的形势非常严峻,已成为全球性的问题。依据全国真菌病监测网的相关数据,目前造成侵袭性感染的酵母及酵母样真菌主要包括念珠属、隐球菌属、毛孢子菌属等[28-29]。不同物种的耐药率存在较大差异。例如,我国侵袭性念珠菌感染中,白念珠菌占32.9%,但其整体耐药水平并不高(约 < 5%的菌株对氟康唑表现为不敏感);而热带念珠菌引起的侵袭性念珠菌感染占18.7%,但36.5%的菌株对氟康唑表现为不敏感。同时,不同地区的同一菌株可能也会存在较大差异。例如,在我国台湾地区引发侵袭性感染热带念珠菌则有16.9%对氟康唑表现为不敏感[30]。

从公共卫生的角度来说,需要关注的是一些较特殊的耐药真菌。可能是新出现的病原真菌(如2009年发现的耳念珠菌),也可能是常见病原真菌的某一个特定耐药谱系。例如,研究发现我国白念珠菌出现一个对唑类药物全耐药的谱系(命名为Clade 1-α),而且已经在我国有一定规模传播[31]。类似的情况在热带念珠菌、希木龙念珠菌、烟曲霉等其他病原真菌中也有发现[32-36]。其中,烟曲霉的唑类耐药性已经引起全球性关注[37]。

和大多数病原真菌一样,这些特殊耐药的病原真菌致病力并不强,主要影响免疫力受损的人群,有时也可作为正常人的共生菌而存在。而且由于病原真菌在自然环境的存活能力较强,为菌株传播(尤其是远距离传播)提供了便利。以白念珠菌的Clade 1-α为例,虽然这个谱系是近期分化出来的,但在广州、哈尔滨等相距较远的城市均有发现,也从侧面反映出病原真菌的传播能力[31]。

目前,国内对病原真菌的公共卫生监测并未系统开展,缺少疾病负担资料,特殊耐药真菌的流行情况并不清晰。以耳念珠菌为例,截至2022年12月文献共报告60例,其中沈阳市39例、北京市4例、厦门市1例、香港地区15例、台湾地区1例[38],但真实情况可能更严重。由于欠缺以基因组数据为基础的分析,目前无法判断有多少常见的病原真菌中已经出现了特殊的耐药谱系。此外,对于已经发生体外耐药或不敏感的菌株,其与临床结局的相关性也缺乏准确了解。

特殊耐药真菌的出现和扩散,主要由于抗真菌药物的选择压力。这些选择压力不仅来自临床上抗真菌药物,也来自农业杀菌剂[39-40]。目前已有证据表明,由于农用唑类杀真菌剂和抗真菌唑类药物之间的分子结构相似,一定程度导致烟曲霉的唑类耐药[41]。由于短期内很难改变杀菌剂和抗真菌药物使用方式,对于特殊耐药真菌(包括感染后的临床结局)的监测非常重要。

3. 区域性真菌感染:一般指在特定地理区域高发的真菌感染,其病原真菌通常为双相真菌[42]。涉及区域性真菌感染通常具备较强的致病力,有时也对免疫正常的个体造成侵袭性感染。现已开始呈现向非传统高发区域扩散的趋势。目前,在我国境内引起区域性真菌感染,主要包括马尔尼菲篮状菌病和孢子丝菌病。

传统上认为,马尔尼菲篮状菌感染的病例主要集中于中国南方地区(尤其是广东省和广西壮族自治区),主要感染HIV患者。广东省HIV患者中约有9.5%~18.8%感染马尔尼菲篮状菌,死亡率约为14.0%~25.1%。广西壮族自治区HIV患者中有16.1%感染马尔尼菲篮状菌,死亡率约为25.0%[43-47]。但近年来,马尔尼菲篮状菌的发病区域有快速扩大趋势。发病区域由中国南部、东南亚地区国家和印度东北部扩展到全球34个国家和地区,包括中国北部、印度东部、朝鲜半岛、日本、澳大利亚东部、美国中部和非洲西部的部分地区[48]。另一方面,非HIV患者感染同样需要引起足够的重视。由于马尔尼菲篮状菌感染无特异性的典型症状,很容易被诊断为结核病、细菌性肺炎、肺癌或其他疾病[49]。现有研究认为马尔尼菲篮状菌病例中,约10%为非HIV患者[50]。血液恶性肿瘤、结肠癌、重症肌无力、混合结缔组织疾病、移植排斥反应、系统性红斑狼疮、糖尿病、糖皮质激素、免疫抑制剂使用或抗干扰素-γ自身抗体升高者等非HIV患者有更高的马尔尼菲篮状菌感染风险[51-52]。因此,有必要对我国马尔尼菲篮状菌感染进行系统性监测,包括非HIV患者和非传统高风险地区。

孢子丝菌病系由孢子丝菌属的物种引起,主要病原菌包括巴西孢子丝菌、申克孢子丝菌和球形孢子丝菌[53]。我国以球形孢子丝菌的感染为主,感染人群主要集于东北地区,其中以吉林省最常见[54]。一般认为,环境中的孢子丝菌经由皮肤破损处感染人体,因此,感染人群以农林从事人员为主。临床上,孢子丝菌病可呈现为固定型(病灶局限于皮肤破损处)、淋巴管型(病灶沿淋巴管向心性发展)和播散型(全身性多处出现病灶)。目前尚未发现不同临床特征和病原菌之间的联系[55]。由于缺乏面向普通人群的系统性流行病学调查,如发病率等流行病学特征暂不明确。

此外,我国某些地区的头癣也需要引起关注。头癣是由皮肤癣菌引起的头皮和头发感染。从生态学特征来说,皮肤癣菌可分为亲人型、亲动物型和亲土型3个生态型。1985年前我国的头癣以亲人型皮肤癣菌感染为主,此后则以亲动物型皮肤癣菌感染为主[56]。这可能与生活状态的改变有关,特别是个人卫生情况的改善和宠物饲养的增加。目前,我国大多数地区的头癣以犬小孢子菌感染为主(65.2%)[57]。犬小孢子菌以猫、狗等为天然宿主,但也非常容易感染人类[58]。因此,犬小孢子菌引发的头癣普遍传播很可能与宠物饲养直接相关,是一种重要的人兽共患疾病。但新疆地区头癣致病性病原真菌仍然以亲人型皮肤癣菌感染为主[56-57],是否由特殊的病原真菌造成仍有待于进一步分析。

4. 病原真菌的院内感染:除少数高致病性真菌以外,病原真菌可能引发的公共卫生事件为院内感染。这主要由于很多住院患者本身免疫力相对低下,而且人员相对集中。同时,相比于细菌和病毒,真菌对于自然环境的生存能力更高。例如,耳念珠菌在自然环境中存活能力较强,能在非生物表面(如塑料、钢铁表面)存活数月[59]。也对消杀方案提出了更高的要求。

由病原真菌导致的院内感染,很早就引起了关注[60-61],常见病原真菌种类包括念珠菌属、曲霉属、毛霉目和镰刀菌属[62]。由于住院患者的免疫力受损,非常见的病原真菌也可能会导致院内感染的发生甚至暴发[63-64]。因此,院内感染控制也需要关注这些非常见的病原真菌。

由于环境中接触到病原真菌的可能性非常大,自20世纪90年代起就开始尝试针对病原真菌感染的高风险人群进行抗真菌的预防性用药[65-66]。但考虑到抗真菌药物的副作用、经济负担,以及可能的耐药性风险,预防性用药的合理性和具体落实方案仍需进一步分析。故院内感染的高风险区域,对于病原真菌的环境监测(包括对耐药真菌监测)、有效消毒和手卫生显得尤为重要。

5. 总结:我国地理环境复杂多样,微生物资源丰富。未知病原真菌的种类可能远超过目前的认知。当人类活动开始涉及到这些区域时,这些隐藏的公共卫生风险会逐步暴露出来。另一方面,现代交通便利也在一定程度上加速了病原真菌的传播。

多数病原真菌的侵袭性感染症状并无特异性,因此经常被诊断为不明原因肺炎、脑炎、发热。甚至有时患者并没有明确症状,只是呈现为低烧。由于诊断困难,且长期缺乏系统性的监测,目前国内病原真菌相关公共卫生风险的真实情况,可能远比表面看起来严峻。

因此,病原真菌相关的公共卫生风险需要引起我国疾控部门的高度重视,尤其要从公共卫生角度建立系统性的全国性和区域性病原真菌监测体系,以进一步明确我国病原真菌相关公共卫生风险,为针对性强化病原真菌防控措施提供支撑。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 龚杰:文献资料查阅、论文撰写、经费支持;耿圆圆、张舒、吴伟伟:文献资料查阅、论文撰写;刘伟、李若瑜、张建中:研究指导、论文修改

| [1] |

Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NAR, et al. Hidden killers: Human fungal infections[J]. Sci Transl Med, 2012, 4(165): 165rv13. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404 |

| [2] |

Blackwell M. The Fungi: 1, 2, 3 ⋯ 5.1 million species?[J]. Am J Bot, 2011, 98(3): 426-438. DOI:10.3732/ajb.1000298 |

| [3] |

Hawksworth DL, Lücking R. Fungal diversity revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 million species[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2017, 5(4): FUNK-0052-2016. DOI:10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0052-2016 |

| [4] |

Fisher MC, Gurr SJ, Cuomo CA, et al. Threats posed by the fungal kingdom to humans, wildlife, and agriculture[J]. mBio, 2020, 11(3): e00449-20. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00449-20 |

| [5] |

Köhler JR, Casadevall A, Perfect J. The spectrum of fungi that infects humans[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2014, 5(1): a019273. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a019273 |

| [6] |

Köhler JR, Hube B, Puccia R, et al. Fungi that infect humans[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2017, 5(3): FUNK-0014-2016. DOI:10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0014-2016 |

| [7] |

Rokas A. Evolution of the human pathogenic lifestyle in fungi[J]. Nat Microbiol, 2022, 7(5): 607-619. DOI:10.1038/s41564-022-01112-0 |

| [8] |

Jackson AP, Gamble JA, Yeomans T, et al. Comparative genomics of the fungal pathogens Candida dubliniensis and Candida albicans[J]. Genome Res, 2009, 19(12): 2231-2244. DOI:10.1101/gr.097501.109 |

| [9] |

Shen XX, Opulente DA, Kominek J, et al. Tempo and mode of genome evolution in the budding yeast subphylum[J]. Cell, 2018, 175(6): 1533-1545, e20. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.023 |

| [10] |

中华人民共和国卫生部. 卫科教发[2006]15号卫生部关于印发《人间传染的病原微生物名录》的通知[EB/OL]. 北京: 中华人民共和国卫生部, 2006. (2006-01-11)[2023-06-15]. http://law.foodmate.net/show-171629.html.

|

| [11] |

Sepúlveda VE, Márquez R, Turissini DA, et al. Genome sequences reveal cryptic speciation in the human pathogen Histoplasma capsulatum[J]. mBio, 2017, 8(6): e01339-17. DOI:10.1128/mBio.01339-17 |

| [12] |

Brown EM, McTaggart LR, Zhang SX, et al. Phylogenetic analysis reveals a cryptic species Blastomyces gilchristii, sp. nov. within the human pathogenic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(3): e59237. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0059237 |

| [13] |

Hrycyk MF, Garces HG, de Moraes Gimenes Bosco S, et al. Ecology of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, P. lutzii and related species: infection in armadillos, soil occurrence and mycological aspects[J]. Med Mycol, 2018, 56(8): 950-962. DOI:10.1093/mmy/myx142 |

| [14] |

Huang WM, Fan YM, Li W, et al. Brain abscess caused by Cladophialophora bantiana in China[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2011, 60(Pt12): 1872-1874. DOI:10.1099/jmm.0.032532-0 |

| [15] |

Pan B, Chen M, Pan WH, et al. Histoplasmosis: a new endemic fungal infection in China? Review and analysis of cases[J]. Mycoses, 2013, 56(3): 212-221. DOI:10.1111/myc.12029 |

| [16] |

Gauthier GM. Dimorphism in fungal pathogens of mammals, plants, and insects[J]. PLoS Pathog, 2015, 11(2): e1004608. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004608 |

| [17] |

Boyce KJ, Andrianopoulos A. Fungal dimorphism: the switch from hyphae to yeast is a specialized morphogenetic adaptation allowing colonization of a host[J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2015, 39(6): 797-811. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuv035 |

| [18] |

Sil A, Andrianopoulos A. Thermally dimorphic human fungal pathogens—polyphyletic pathogens with a convergent pathogenicity trait[J]. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2014, 5(8): a019794. DOI:10.1101/cshperspect.a019794 |

| [19] |

Revankar SG, Sutton DA. Melanized fungi in human disease[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2010, 23(4): 884-928. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00019-10 |

| [20] |

Seyedmousavi S, Netea MG, Mouton JW, et al. Black yeasts and their filamentous relatives: Principles of pathogenesis and host defense[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2014, 27(3): 527-542. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00093-13 |

| [21] |

Yang XY, Song YG, Liang TY, et al. Application of laser capture microdissection and PCR sequencing in the diagnosis of Coccidioides spp. infection: A case report and literature review in China[J]. Emerg Microbes Infec, 2021, 10(1): 331-341. DOI:10.1080/22221751.2021.1889931 |

| [22] |

赵蓓蕾, 施毅, 印洁, 等. 我国部分地区组织胞浆菌感染的流行病学调查[J]. 医学研究生学报, 2003, 16(3): 199-202. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-8199.2003.03.015 Zhao BL, Shi Y, Yin J, et al. Study on epidemiology of Histoplasma capsulatum infection in China[J]. J Med Postgrad, 2003, 16(3): 199-202. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1008-8199.2003.03.015 |

| [23] |

吴鄂生, 孙翊道, 赵蓓蕾, 等. 中南邵阳、华东南京、西南成都组织胞浆菌感染流行病学调查[J]. 中国现代医学杂志, 2002, 12(24): 50-52. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-8982.2002.24.016 Wu ES, Sun YD, Zhao BL, et al. Investigation on the epidemiology of Histoplasm capsulatum infection in central south (Shao Yang), east of China (Nan Jing) and western south (Cheng du)[J]. China J Mod Med, 2002, 12(24): 50-52. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-8982.2002.24.016 |

| [24] |

赵蓓蕾, 印洁, 夏锡荣, 等. 南京地区组织胞浆菌感染的流行病学调查[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 1998, 19(4): 215-217. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.1998.04.006 Zhao BL, Yin J, Xia XR, et al. Investigation on the epidemiology of Histoplasma capsulatum infection in Nanjing district[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 1998, 19(4): 215-217. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0254-6450.1998.04.006 |

| [25] |

Robbins N, Wright GD, Cowen LE. Antifungal drugs: The current armamentarium and development of new agents[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2016, 4(5): FUNK-0002-2016. DOI:10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0002-2016 |

| [26] |

Fisher MC, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Berman J, et al. Tackling the emerging threat of antifungal resistance to human health[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2022, 20(9): 557-571. DOI:10.1038/s41579-022-00720-1 |

| [27] |

Ademe M, Girma F. Candida auris: From multidrug resistance to pan-resistant strains[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2020, 13: 1287-1294. DOI:10.2147/idr.S249864 |

| [28] |

Xiao M, Chen SCA, Kong FR, et al. Distribution and antifungal susceptibility of Candida species causing candidemia in China: An update from the CHIF-NET study[J]. J Infect Dis, 2020, 221 Suppl 2: S139-147. DOI:10.1093/infdis/jiz573 |

| [29] |

Xiao M, Chen SCA, Kong FR, et al. Five-year China Hospital Invasive Fungal Surveillance Net (CHIF-NET) study of invasive fungal infections caused by noncandidal yeasts: species distribution and azole susceptibility[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2018, 11: 1659-1667. DOI:10.2147/IDR.S173805 |

| [30] |

Chen PY, Chuang YC, Wu UI, et al. Clonality of fluconazole-nonsusceptible Candida tropicalis in bloodstream infections, Taiwan, 2011-2017[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2019, 25(9): 1668-1675. DOI:10.3201/eid2509.190520 |

| [31] |

Gong J, Chen XF, Fan X, et al. Emergence of antifungal resistant subclades in the global predominant phylogenetic population of Candida albicans[J]. Microbiol Spectr, 2023, 11(1): e03807-22. DOI:10.1128/spectrum.03807-22 |

| [32] |

Fan X, Xiao M, Liao K, et al. Notable increasing trend in azole non-susceptible Candida tropicalis causing invasive candidiasis in China (August 2009 to July 2014): Molecular epidemiology and clinical azole consumption[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 464. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00464 |

| [33] |

Fan X, Xiao M, Zhang D, et al. Molecular mechanisms of azole resistance in Candida tropicalis isolates causing invasive candidiasis in China[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2019, 25(7): 885-891. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.007 |

| [34] |

Chen XF, Jia XM, Bing J, et al. Clonal dissemination of antifungal-resistant Candida haemulonii, China[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2023, 29(3): 576-584. DOI:10.3201/eid2903.221082 |

| [35] |

Sewell TR, Zhu JN, Rhodes J, et al. Nonrandom distribution of azole resistance across the global population of Aspergillus fumigatus[J]. mBio, 2019, 10(3): e00392-19. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00392-19 |

| [36] |

Rhodes J, Abdolrasouli A, Dunne K, et al. Population genomics confirms acquisition of drug-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus infection by humans from the environment[J]. Nat Microbiol, 2022, 7(5): 663-674. DOI:10.1038/s41564-022-01091-2 |

| [37] |

Wiederhold NP, Verweij PE. Aspergillus fumigatus and pan-azole resistance: Who should be concerned?[J]. Curr Opin Infect Dis, 2020, 33(4): 290-297. DOI:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000662 |

| [38] |

Du H, Bing J, Nobile CJ, et al. Candida auris infections in China[J]. Virulence, 2022, 13(1): 589-591. DOI:10.1080/21505594.2022.2054120 |

| [39] |

Azevedo MM, Faria-Ramos I, Cruz LC, et al. Genesis of azole antifungal resistance from agriculture to clinical settings[J]. J Agric Food Chem, 2015, 63(34): 7463-7468. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.5b02728 |

| [40] |

Bastos RW, Rossato L, Goldman GH, et al. Fungicide effects on human fungal pathogens: Cross-resistance to medical drugs and beyond[J]. PLoS Pathog, 2021, 17(12): e1010073. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1010073 |

| [41] |

Meis JF, Chowdhary A, Rhodes JL, et al. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus[J]. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2016, 371(1709): 20150460. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2015.0460 |

| [42] |

Proia L, Miller R. Endemic fungal infections in solid organ transplant recipients[J]. Am J Transplant, 2009, 9 Suppl 4: S199-207. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02912.x |

| [43] |

黄丽芬, 唐小平, 蔡卫平, 等. 广东地区762例住院人类免疫缺陷病毒感染患者机会性感染分析[J]. 中华内科杂志, 2010, 49(8): 653-656. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2010.08.006 Huang LF, Tang XP, Cai WP, et al. An analysis of opportunistic infection in 762 inpatients with human immunodeficiency virus infection in Guangdong areas[J]. Chin J Intern Med, 2010, 49(8): 653-656. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2010.08.006 |

| [44] |

Ying RS, Le T, Cai WP, et al. Clinical epidemiology and outcome of HIV-associated talaromycosis in Guangdong, China, during 2011-2017[J]. HIV Med, 2020, 21(11): 729-738. DOI:10.1111/hiv.13024 |

| [45] |

黄丽芬, 邓子德, 叶晓新, 等. 345例艾滋病死亡病例的医院感染状况分析[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2013, 12(3): 178-181. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-9638.2013.03.005 Huang LF, Deng ZD, Ye XX, et al. Healthcare-associated infection in 345 HIV/AIDS death cases[J]. Chin J Infect Control, 2013, 12(3): 178-181. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-9638.2013.03.005 |

| [46] |

Qin YY, Huang XJ, Chen H, et al. Burden of Talaromyces marneffei infection in people living with HIV/AIDS in Asia during ART era: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2020, 20(1): 551. DOI:10.1186/s12879-020-05260-8 |

| [47] |

Jiang J, Meng S, Huang S, et al. Effects of Talaromyces marneffei infection on mortality of HIV/AIDS patients in southern China: a retrospective cohort study[J]. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2019, 25(2): 233-241. DOI:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.04.018 |

| [48] |

Wei WD, He JH, Ning CY, et al. Maxent modeling for predicting the potential distribution of global talaromycosis[J]. bioRxiv, 2021. DOI:10.1101/2021.03.28.437430 |

| [49] |

Castro-Lainez MT, Sierra-Hoffman M, LLompart-Zeno J, et al. Talaromyces marneffei infection in a non-HIV non-endemic population[J]. IDCases, 2018, 12: 21-24. DOI:10.1016/j.idcr.2018.02.013 |

| [50] |

Wang F, Han RH, Chen S. An overlooked and underrated endemic mycosis-talaromycosis and the pathogenic fungus Talaromyces marneffei[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2023, 36(1): e00051-22. DOI:10.1128/cmr.00051-22 |

| [51] |

Chan JFW, Lau SKP, Yuen KY, et al. Talaromyces (Penicillium) marneffei infection in non-HIV-infected patients[J]. Emerg Microbes Infec, 2016, 5(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1038/emi.2016.18 |

| [52] |

Guo J, Li BK, Li TM, et al. Characteristics and prognosis of Talaromyces marneffei infection in non-HIV-infected children in southern China[J]. Mycopathologia, 2019, 184(6): 735-745. DOI:10.1007/s11046-019-00373-4 |

| [53] |

Rodrigues AM, Terra PPD, Gremião ID, et al. The threat of emerging and re-emerging pathogenic Sporothrix species[J]. Mycopathologia, 2020, 185(5): 813-842. DOI:10.1007/s11046-020-00425-0 |

| [54] |

Lv S, Hu X, Liu Z, et al. Clinical epidemiology of Sporotrichosis in Jilin province, China (1990-2019): A series of 4 969 cases[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2022, 15: 1753-1765. DOI:10.2147/idr.S354380 |

| [55] |

Gong J, Zhang MR, Wang Y, et al. Population structure and genetic diversity of Sporothrix globosa in China according to 10 novel microsatellite loci[J]. J Med Microbiol, 2019, 68(2): 248-254. DOI:10.1099/jmm.0.000896 |

| [56] |

Zhan P, Li DM, Wang C, et al. Epidemiological changes in tinea capitis over the sixty years of economic growth in China[J]. Med Mycol, 2015, 53(7): 691-698. DOI:10.1093/mmy/myv057 |

| [57] |

Chen XQ, Zheng DY, Xiao YY, et al. Aetiology of tinea capitis in China: a multicentre prospective study[J]. Brit J Dermatol, 2022, 186(4): 705-712. DOI:10.1111/bjd.20875 |

| [58] |

Pasquetti M, Min ARM, Scacchetti S, et al. Infection by Microsporum canis in paediatric patients: A veterinary perspective[J]. Vet Sci, 2017, 4(3): 46. DOI:10.3390/vetsci4030046 |

| [59] |

Kean R, Sherry L, Townsend E, et al. Surface disinfection challenges for Candida auris: an in-vitro study[J]. J Hosp Infect, 2018, 98(4): 433-436. DOI:10.1016/j.jhin.2017.11.015 |

| [60] |

Fridkin SK, Jarvis WR. Epidemiology of nosocomial fungal infections[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 1996, 9(4): 499-511. DOI:10.1128/CMR.9.4.499 |

| [61] |

Walsh TJ, Pizzo PA. Nosocomial fungal infections: A classification for hospital-acquired fungal infections and mycoses arising from endogenous flora or reactivation[J]. Annu Rev Microbiol, 1988, 42: 517-545. DOI:10.1146/annurev.mi.42.100188.002505 |

| [62] |

Perlroth J, Choi B, Spellberg B. Nosocomial fungal infections: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment[J]. Med Mycol, 2007, 45(4): 321-346. DOI:10.1080/13693780701218689 |

| [63] |

Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Rare and emerging opportunistic fungal pathogens: Concern for resistance beyond Candida albicans and Aspergillus fumigatus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2004, 42(10): 4419-4431. DOI:10.1128/JCM.42.10.4419-4431.2004 |

| [64] |

Repetto EC, Giacomazzi CG, Castelli F. Hospital-related outbreaks due to rare fungal pathogens: a review of the literature from 1990 to June 2011[J]. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis, 2012, 31(11): 2897-2904. DOI:10.1007/s10096-012-1661-3 |

| [65] |

Kaufman D, Boyle R, Hazen KC, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and infection in preterm infants[J]. N Engl J Med, 2001, 345(23): 1660-1666. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa010494 |

| [66] |

Winston DJ, Chandrasekar PH, Lazarus HM, et al. Fluconazole prophylaxis of fungal infections in patients with acute leukemia: Results of a randomized placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial[J]. Ann Intern Med, 1993, 118(7): 495-503. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00003 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44