文章信息

- 王浩, 周怡, 戴品远, 李娜, 关云琦, 潘劲, 钟节鸣, 俞敏.

- Wang Hao, Zhou Yi, Dai Pinyuan, Li Na, Guan Yunqi, Pan Jin, Zhong Jieming, Yu Min

- 浙江省中学生焦虑抑郁症状共病状况分析

- Comorbidity of anxiety symptoms and depression symptoms among middle and high school students in Zhejiang Province

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(12): 1921-1927

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(12): 1921-1927

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230722-00032

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-07-22

2. 浙江中医药大学公共卫生学院, 杭州 310053

2. School of Public Health, Zhejiang Chinese Medical University, Hangzhou 310053, China

焦虑抑郁症状共病是指同一个体在某一时期同时出现焦虑、抑郁症状,且两者分别满足各自的筛查标准[1]。中学生焦虑和抑郁症状常呈现重叠,共病现象普遍存在[2]。2021年中国8个城市调查数据显示,超过30%的中学生存在焦虑抑郁症状共病[3]。同时有研究报道,新型冠状病毒疫情期间,出现焦虑抑郁症状的学生比例增加[4]。中学生群体由于身心发育不成熟,与成年人相比,面对学习、生活和社交等压力时出现焦虑抑郁共病的风险更高[5]。国内外关于中学生焦虑抑郁的研究多关注于单一的焦虑或抑郁[6-8]。本研究利用2022年浙江省青少年健康危险因素调查数据,对中学生焦虑抑郁症状共病状况进行分析,为今后制定干预政策提供依据。

对象与方法1. 调查对象:采用多阶段分层整群抽样的方法。第一阶段:在浙江省90个市(县、区)中随机抽取30个(杭州市上城区、杭州市拱墅区、杭州市富阳区、建德市、宁波市海曙区、宁波市奉化区、余姚市、温州市鹿城区、平阳县、乐清市、嘉兴市南湖区、嘉善县、桐乡市、湖州市吴兴区、安吉县、绍兴市越城区、绍兴市上虞区、新昌县、金华市婺城区、东阳市、武义县、衢州市柯城区、开化县、舟山市普陀区、台州市椒江区、仙居县、温岭市、丽水市莲都区、遂昌县及云和县);第二阶段:采用单纯随机抽样法,在每个抽中的市(县、区),分别从初中、普通高中和非普通高中班级中,抽取11个初中班级、6个普通高中班级和6个非普通高中班级。非普通高中包括职业高中、普通中等专业学校和技工学校等;第三阶段:采用整群抽样方法,对抽中班级的全部在校生进行调查。本次调查不包括成人初中、成人高中、成人中等专业学校以及残疾人学校。

2. 调查内容:调查采用统一的调查问卷。问卷设计参考美国CDC的青少年行为危险因素监测问卷[9]和WHO的全球青少年健康监测问卷[10],以往文献报道问卷具有良好的信度和效度[11-12]。问卷包括人口社会学、吸烟、饮酒、体育活动、心理健康和校园安全等内容。焦虑症状采用广泛性焦虑量表(GAD-7)。GAD-7主要询问过去2周精神情绪变化,内容包括“感到紧张焦虑愤怒”“不能停止控制担忧”“对各种事情担忧多”“难以放松”“不安而无法静坐”“易烦恼急躁”“感到将有可怕的事情发生而害怕”。选项包括“没有”“有几天”“一半以上日子”“几乎每天”。分别赋值0~3分,得分范围为0~21分;以往文献发现焦虑量表得分切点取10时,灵敏度和特异度达到最大[13]。抑郁症状筛查采用患者健康问卷抑郁量表(PHQ-9)。PHQ-9主要询问过去2周的感受,内容包括“做事没兴趣”“心情低落沮丧”“入睡困难/睡不安”“疲倦没活力”“食欲不振/吃太多”“感觉自身失败”“对事物专注有困难”“动作/说话缓慢或正好相反”“有伤害自己的念头”。选项和赋值同GAD-7,得分范围为0~27分。PHQ-9得分切点取10时,具有较高的灵敏度(88%)和特异度(85%)[14]。因此本研究焦虑和抑郁症状阳性判断的切点均采用10。同时为了和已有研究进行比较,本研究也报告切点为5的焦虑抑郁症状共病率。

3. 调查方法:2022年4-6月,经过统一培训的市(县、区)CDC工作人员开展现场调查。采用自我管理式问卷调查,学生在教室统一集中填写。现场调查开始前,调查员统一向学生讲解调查目的和意义;强调调查的匿名性,向学生说明学校老师、家长均不会知道选项;作答与学习成绩无关。调查过程中,学生至少保持1 m间距,教室保持安静,校医和老师均回避。填好的问卷由学生亲手投入密封的问卷回收箱。调查获得浙江省CDC伦理委员会审查(批准文号:2022-007-01)。现场调查前1周,CDC下发纸质知情同意书,知情同意书采用调查学生及其家长双签名。

4. 统计学分析:采用SAS 9.4软件进行统计学分析。由于采用多阶段复杂抽样设计,在数据分析时考虑复杂加权。加权方法见文献[15]。计数资料描述采用百分比(95%CI)。以基于复杂抽样设计的率的Rao-Scott χ2检验比较不同特征学生焦虑抑郁症状共病率的差异。以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。多重比较采用Bonferroni校正法,3种不同类型学校间多重比较的显著性阈值设定为0.05/3=0.017,4种不同自报健康状况间多重比较的显著性阈值设定为0.05/4=0.012。

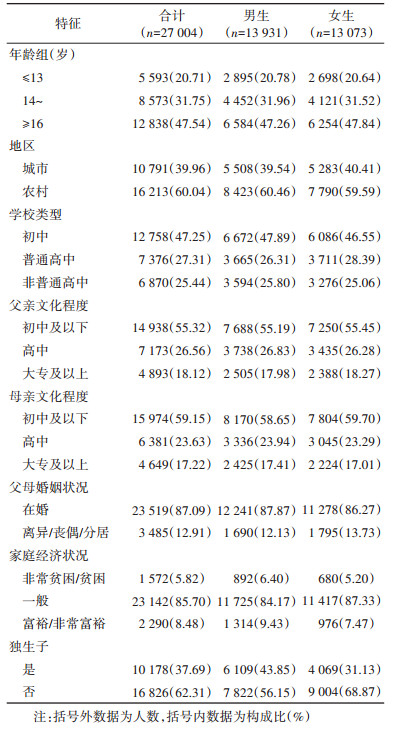

结果1. 一般情况:共抽中的376个班级,共有学生28 043名,其中114名拒绝调查、859名调查当日不在学校,应答率为96.53%。剔除填写问卷不完整40份、GAD-7和PHQ-9中任一缺项问卷26份,最终纳入分析27 004名,年龄为(15.75±1.73)岁,其中男生13 931名(51.59%),女生13 073名(48.41%);初中生12 758名(47.25%),普通高中生7 376名(27.31%),非普通高中生6 870名(25.44%)。见表 1。

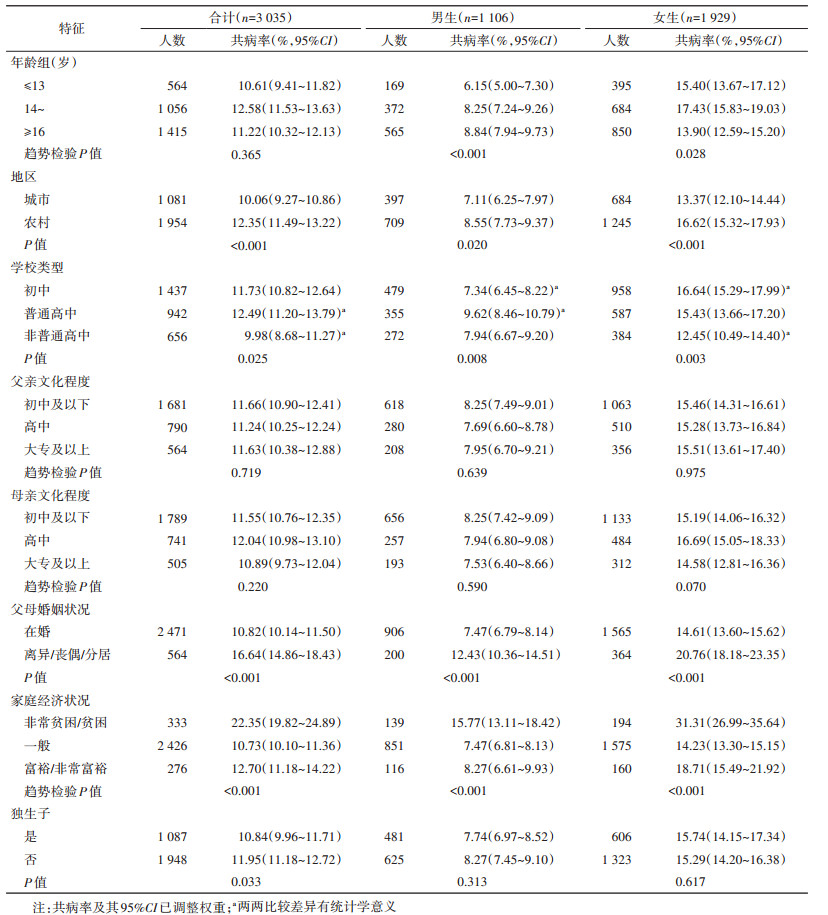

2. 不同社会人口学特征中学生焦虑抑郁症状共病:中学生焦虑抑郁症状共病率为11.54%(95%CI:10.90%~12.19%),女生(15.42%,95%CI:14.47%~16.38%)高于男生(8.05%,95%CI:7.43%~8.67%)(P < 0.001);农村(12.35%,95%CI:11.49%~13.22%)高于城市(10.06%,95%CI:9.27%~10.86%)(P < 0.001);初中、普通高中和非普通高中学生共病率分别为11.73%(95%CI:10.82%~12.64%)、12.49%(95%CI:11.20%~13.79%)和9.98%(95%CI:8.68%~11.27%)(P=0.025)。两两之间比较结果显示,普通高中学生共病率高于非普通高中(P=0.008),初中男生共病率低于普通高中男生(P=0.002),初中女生共病率高于非普通高中女生(P < 0.001),差异均有统计学意义;离异/丧偶/分居家庭的学生共病率(16.64%,95%CI:14.86%~18.43%)高于在婚家庭(10.82%,95%CI:10.14%~11.50%)(P < 0.001);家庭经济状况越好的学生共病率越低(P < 0.001)。见表 2。采用切点5计算的焦虑抑郁症状共病率为42.51%(95%CI:41.25%~43.78%)。

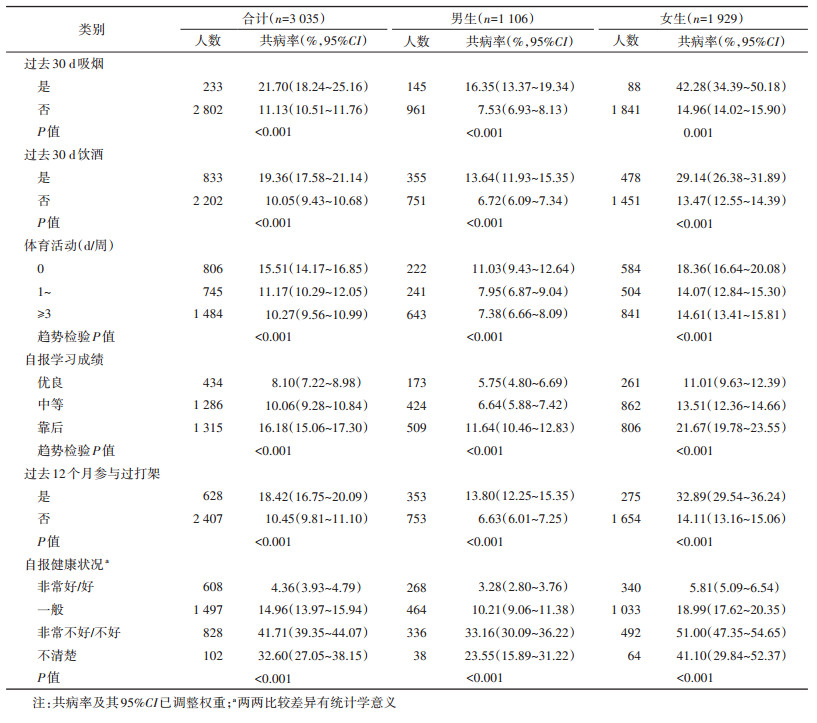

3. 不同行为和健康状况中学生焦虑抑郁症状共病:过去30 d吸烟者焦虑抑郁症状共病率(21.70%,95%CI:18.24%~25.16%)高于未吸烟者(11.13%,95%CI:10.51%~11.76%);过去30 d饮酒者共病率(19.36%,95%CI:17.58%~21.14%)高于未饮酒者(10.05%,95%CI:9.43%~10.68%);体育活动0、1~、≥3 d/周的学生共病率分别为15.51%(95%CI:14.17%~16.85%)、11.17%(95%CI:10.29%~12.05%)和10.27%(95%CI:9.56%~10.99%)。共病率随每周体育活动天数增加而降低(P < 0.001);自报学习成绩优良、中等和靠后的学生共病率分别为8.10%(95%CI:7.22%~8.98%)、10.06%(95%CI:9.28%~10.84%)和16.18%(95%CI:15.06%~17.30%)。自报学习成绩越差的学生,共病率越高(P < 0.001);自报健康状况为非常好/好、一般、非常不好/不好和不清楚的学生共病率分别为4.36%(95%CI:3.93%~4.79%)、14.96%(95%CI:13.97%~15.94%)、41.71%(95%CI:39.35%~44.07%)和32.60%(95%CI:27.05%~38.15%);过去12个月参与过打架者共病率(18.42%,95%CI:16.75%~20.09%)高于未参与过者(10.45%,95%CI:9.81%~11.10%)。见表 3。

本研究结果显示,超过10%的中学生存在焦虑抑郁症状共病的情况。一项研究于2021年10-12月对我国4个一线城市(深圳、重庆、郑州和沈阳)和4个二线城市(昆明、徐州、太原和南昌),共27所学校22 868名初中和高中学生[年龄(14.6±1.8)岁]采用PHQ-9问卷和GAD-7问卷进行筛查(阳性判定切点为5),发现中学生焦虑抑郁症状共病率为31.6%[3],低于本研究采用切点5计算的结果(42.51%)。分析原因可能与调查省份、抽样方法、学校类型构成等因素不同有关,也可能与新型冠状病毒疫情对青少年心理健康影响有关[4]。

美国一项针对12~17岁青少年研究发现,女生焦虑抑郁共病率(28.4%)高于男生(17.1%)[16],与本研究结果一致。可能与女生在青春期气质脆弱性、负面认知水平以及压力较大,更易沉溺于负性情绪的被动思考有关[17]。从学校类型来看,普通高中学生共病率高于非普通高中,这可能与普通高中的学生学业重,升学压力大有关。以往有文献报道与非独生子女相比,独生子女更倾向于自我为中心,与同伴相处困难,易出现悲观和心理问题[18-19]。中国山东省一项研究对645名大学生调查发现,独生子女焦虑抑郁症状共病率高于非独生子女[20]。然而本研究结果显示,在男生和女生中,独生子女和非独生子女相比,焦虑抑郁症状共病率差异无统计学意义。两者是否存在关联有待于大样本深入研究。

与其他文献报道一致,吸烟和饮酒人群中焦虑抑郁症状共病率高于不吸烟者和不饮酒者[21-22],体育锻炼少的人群共病率高于体育锻炼频繁的人群[3];加拿大一项研究对57 394名中学生调查发现,学习成绩好的学生,往往心理健康量表得分高而抑郁量表评分低[23]。本研究发现,学习成绩越靠后的学生共病率越高。这可能与成绩靠后的学生承受更多来自老师和家长的压力,导致缺乏自信,从而产生心理问题[24-25]。此外,本研究结果显示,过去12个月参与过打架者共病率高于未参与过打架者。打架属于躯体欺凌,是欺凌的一种常见类型。文献报道无论欺凌实施者还是受害者,焦虑和抑郁情绪的检出率均高于未参与者[26]。

本研究存在局限性。第一,调查问卷由学生自填,可能会存在信息偏倚;第二,横断面研究仅能说明焦虑抑郁症状共病和其他变量之间存在相关,无法说明因果关联。

综上所述,焦虑抑郁症状共病情况在中学生中常见。提示应进一步重视中学生的心理卫生工作。将心理健康教育课纳入学校课程,传授相关知识和技能,培养中学生积极乐观心理品质。树立求助意识;定期开展心理健康筛查,发现异常,及时疏导,避免造成心理危机。同时加强学校心理咨询辅导服务能力建设,提升心理辅导咨询水平。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 王浩:方案设计、数据清理分析、论文撰写;周怡、戴品远、李娜、关云琦、潘劲:数据收集清理、质量控制;钟节鸣、俞敏:论文审阅、经费和技术支持

志谢 感谢参加2022年浙江省青少年健康危险因素调查的30个市(县、区)的卫生行政部门、教育部门和疾病预防控制中心的大力支持和配合;感谢所有参与现场调查的工作人员

| [1] |

王萌, 陶芳标, 伍晓艳. 儿童青少年焦虑抑郁共病研究进展[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2022, 56(7): 1011-1016. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220325-00283 Wang M, Tao FB, Wu XY. Research progress on the comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents[J]. Chin J Prev Med, 2022, 56(7): 1011-1016. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112150-20220325-00283 |

| [2] |

Leyfer O, Gallo KP, Cooper-Vince C, et al. Patterns and predictors of comorbidity of DSM-Ⅳ anxiety disorders in a clinical sample of children and adolescents[J]. J Anxiety Disord, 2013, 27(3): 306-311. DOI:10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.01.010 |

| [3] |

Wang M, Mou XY, Li TT, et al. Association between comorbid anxiety and depression and health risk behaviors among Chinese adolescents: cross-sectional questionnaire study[J]. JMIR Public Health Surveill, 2023, 9: e46289. DOI:10.2196/46289 |

| [4] |

Li YY, Zhao JB, Ma ZJ, et al. Mental health among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A 2-wave longitudinal survey[J]. J Affect Disord, 2021, 281: 597-604. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.109 |

| [5] |

Losada-Baltar A, Márquez-González M, Jiménez-Gonzalo L, et al. Differences in anxiety, sadness, loneliness and comorbid anxiety and sadness as a function of age and self-perceptions of aging during the lock-out period due to COVID-19[J]. Rev Esp Geriatr Gerontol, 2020, 55(5): 272-278. DOI:10.1016/j.regg.2020.05.005 |

| [6] |

Mridha MK, Hossain MM, Khan MSA, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of depression among adolescent boys and girls in Bangladesh: findings from a nationwide survey[J]. BMJ Open, 2021, 11(1): e038954. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038954 |

| [7] |

Liu HY, Shi YJ, Auden E, et al. Anxiety in rural Chinese children and adolescents: Comparisons across provinces and among subgroups[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2018, 15(10): 2087. DOI:10.3390/ijerph15102087 |

| [8] |

Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19[J]. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2020, 29(6): 749-758. DOI:10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4 |

| [9] |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. YRBSS Questionnaires[EB/OL]. [2023-07-07]. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/questionnaires.htm.

|

| [10] |

World Health Organization. GSHS core questionnaire modules (2018-2020)[EB/OL]. (2021-01-20)[2023-07-07]. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/gshs-core-questionnaire-modules-(2018-2020).

|

| [11] |

Alkhraiji MH, Barker AR, Williams CA. Reliability and validity of using the global school-based student health survey to assess 24 hour movement behaviours in adolescents from Saudi Arabia[J]. J Sports Sci, 2022, 40(14): 1578-1586. DOI:10.1080/02640414.2022.2092982 |

| [12] |

Brener ND, Collins JL, Kann L, et al. Reliability of the youth risk behavior survey questionnaire[J]. Am J Epidemiol, 1995, 141(6): 575-580. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117473 |

| [13] |

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7[J]. Arch Intern Med, 2006, 166(10): 1092-1097. DOI:10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 |

| [14] |

Levis B, Benedetti A, Thombs BD. Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis[J]. BMJ, 2019, 365: l1476. DOI:10.1136/bmj.l1476 |

| [15] |

Wang H, Bragg F, Guan YQ, et al. Association of bullying victimization with suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among school students: A school-based study in Zhejiang Province, China[J]. J Affect Disord, 2023, 323: 361-367. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.11.087 |

| [16] |

Small DM, Simons AD, Yovanoff P, et al. Depressed adolescents and comorbid psychiatric disorders: are there differences in the presentation of depression?[J]. J Abnorm Child Psychol, 2008, 36(7): 1015-1028. DOI:10.1007/s10802-008-9237-5 |

| [17] |

Salk RH, Hyde JS, Abramson LY. Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms[J]. Psychol Bull, 2017, 143(8): 783-822. DOI:10.1037/bul0000102 |

| [18] |

Cameron L, Erkal N, Gangadharan L, et al. Little emperors: behavioral impacts of China's One-Child Policy[J]. Science, 2013, 339(6122): 953-957. DOI:10.1126/science.1230221 |

| [19] |

Chi XL, Huang LY, Wang J, et al. The prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of depressive symptoms in early adolescents in China: Differences in only child and non-only child groups[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, 17(2): 438. DOI:10.3390/ijerph17020438 |

| [20] |

Cheng S, Jia CX, Wang YJ. Only children were associated with anxiety and depressive symptoms among college students in China[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, 17(11): 4035. DOI:10.3390/ijerph17114035 |

| [21] |

Byeon H. Association among smoking, depression, and anxiety: findings from a representative sample of Korean adolescents[J]. PeerJ, 2015, 3: e1288. DOI:10.7717/peerj.1288 |

| [22] |

Johannessen EL, Andersson HW, Bjørngaard JH, et al. Anxiety and depression symptoms and alcohol use among adolescents - a cross sectional study of Norwegian secondary school students[J]. BMC Public Health, 2017, 17(1): 494. DOI:10.1186/s12889-017-4389-2 |

| [23] |

Duncan MJ, Patte KA, Leatherdale ST. Mental health associations with academic performance and education behaviors in Canadian secondary school students[J]. Can J Sch Psychol, 2021, 36(4): 335-357. DOI:10.1177/0829573521997311 |

| [24] |

Valås H. Students with learning disabilities and low-achieving students: peer acceptance, loneliness, self-esteem, and depression[J]. Soc Psychol Educ, 1999, 3(3): 173-192. DOI:10.1023/A:1009626828789 |

| [25] |

Khesht-Masjedi MF, Shokrgozar S, Abdollahi E, et al. The relationship between gender, age, anxiety, depression, and academic achievement among teenagers[J]. J Family Med Prim Care, 2019, 8(3): 799-804. DOI:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_103_18 |

| [26] |

刘小群, 杨孟思, 彭畅, 等. 校园欺凌中不同角色中学生的焦虑抑郁情绪[J]. 中国心理卫生杂志, 2021, 35(6): 475-481. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2021.06.007 Liu XQ, Yang MS, Peng C, et al. Anxiety emotion and depressive mood of middle school students with different roles in school bullying[J]. Chin Ment Health J, 2021, 35(6): 475-481. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6729.2021.06.007 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44