文章信息

- 张润华, 王晶, 李刚, 刘改芬.

- Zhang Runhua, Wang Jing, Li Gang, Liu Gaifen

- 气温对北京市居民缺血性卒中和出血性卒中死亡影响的时间序列研究

- Effect of ambient temperature on mortalities of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke in Beijing: a time series study

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(11): 1802-1807

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(11): 1802-1807

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230310-00137

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-03-10

2. 北京市疾病预防控制中心, 北京 100013

2. Beijing Center for Disease Prevention and Control, Beijing 100013, China

根据全球疾病负担研究,2019年我国有394万例新发卒中病例,219万例死亡归因于卒中,比2009年分别增加123.5%和59.0%[1],卒中已成为导致我国疾病负担的重要原因[2]。为降低卒中疾病负担,识别危险因素至关重要。越来越多的流行病学证据表明,异常的气温可能会增加心脑血管疾病的发病和死亡风险[3-6]。然而,低温和高温对卒中风险的影响结果尚不一致,尤其是对不同卒中亚型的影响。一些研究发现高温可增加出血性卒中死亡风险[4, 7],而另一些研究发现高温与出血性卒中死亡不相关[8],此外,还有研究发现高温对出血性卒中的发生具有保护作用[9]。尽管来自我国的一些省市研究提供了气温与卒中死亡风险的关系,但气温对卒中死亡的效应在不同地区和区域具有一定差异,这可能与当地气候特点、居民对气候长期适应有关[10-12]。我国地域辽阔,气候具有多样性,因此,有必要在局部地区进行相关分析。本研究应用分布滞后非线性模型(DLNM)评价2014-2019年北京市气温对缺血性卒中和出血性卒中死亡风险的影响。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:

(1)气象数据:来源于中国气象科学数据共享服务网,包括2014年1月1日到2019年12月31日的北京市日均气温和日均相对湿度。该数据来源于北京市15个监测点(东城区、西城区为1个监测点),覆盖北京市16个市辖区,采用均值代表北京市日均气温及相对湿度。

(2)空气污染物浓度:来源于北京市生态环境监测中心空气质量实时平台,包括北京市日均空气中粒径≤2.5 μm的颗粒物(PM2.5)、二氧化氮(NO2)、二氧化硫(SO2)、一氧化碳(CO)、每日8 h最大臭氧(O3)浓度。该数据来源于北京市35个监测站发布的每小时空气污染物浓度数据,监测站遍布北京城区及远郊区(县),包括城六区(12个)、西北部(5个)、东北部(8个)、东南部(6个)、西南部(4个)。本研究中使用35个监测站污染物浓度的平均值代表北京市空气污染物浓度水平,具有较好代表性。

(3)卒中死亡资料:来源于北京市CDC的死因监测系统中北京市户籍居民死亡登记资料,包括2014年1月1日至2019年12月31日的卒中死亡登记数据。北京市CDC负责收集本市医疗机构填报的《居民死亡医学证明(推断)书》,获得全市死亡登记信息,并定期与北京市公安、民政部门进行数据核对与补报,从而保证数据的准确性和全面性[13]。该监测系统为全人群监测,覆盖率为100%[13]。采用《国际疾病分类》第十版进行卒中死亡病例统计。卒中死亡定义为根本死因编码为I60~I69,其中缺血性卒中编码为I63、I69.3,出血性卒中编码为I60、I61、I69.0及I69.1。

本研究通过首都医科大学附属北京天坛医院伦理委员会审查(批准文号:KY2020-040-01),由于本研究未涉及个体数据,研究已通过首都医科大学附属北京天坛医院伦理委员会的免知情同意申请。

2.数据分析方法:由于气温与卒中死亡之间的关系存在非线性效应和滞后效应,故采用DLNM进行分析[14]。首先,构建温度的交叉基函数,以卒中每日死亡人数作为因变量,采用准泊松(quasi-Poisson)作为连接函数构建气温与卒中每日死亡人数之间的模型。同时,在模型中校正空气污染物(PM2.5、SO2、NO2、CO、O3)、相对湿度、时间的长期趋势、星期和节假日效应。具体模型:

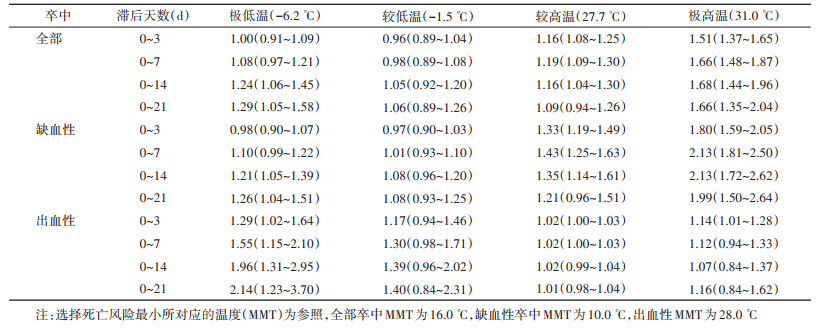

式中,

根据既往研究结果,设定本研究中气温对死亡产生的最长滞后天数为21 d[4, 15],df的设置根据赤池信息准则及既往研究结果,确定交叉基中温度和滞后天数的df均为5,相对湿度、污染物的df均为3,时间长期趋势df为7/年[5, 16-17]。通过温度与卒中死亡之间的关系暴露反应曲线,选择死亡风险最小所对应的温度(MMT)为参照,卒中死亡风险最小时对应的温度为16.0 ℃,缺血性卒中对应的温度为10.0 ℃,出血性卒中对应的温度为28.0 ℃。分别计算极低温(日均气温的P1)、较低温(日均气温的P10)、较高温(日均气温的P90)、极高温(日均气温的P99)在不同的滞后天数(0~3、0~7、0~14、0~21 d)对卒中死亡的滞后效应。研究中依据性别和年龄(< 65岁与≥65岁)进行分层,分析性别和年龄的效应修饰作用。通过计算95%CI来检验潜在效应修饰因子的各层效应估计之间的差异是否有统计学意义[18]。

采用R 3.5.1软件进行数据统计分析,其中DLNM模型采用“dlnm”包,自然立方样条采用“spline”包,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

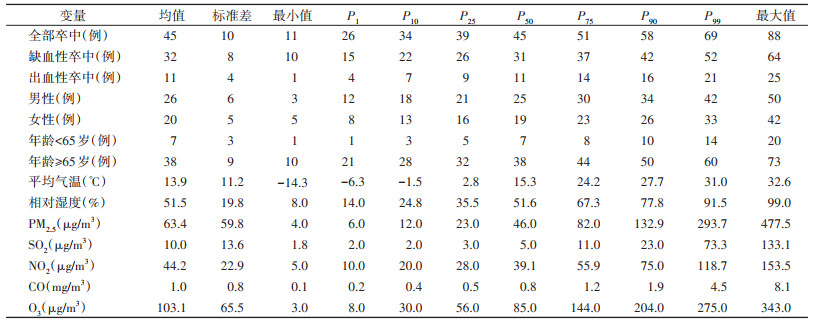

结果1. 基本情况:2014-2019年北京市因卒中死亡人数共99 222例,其中缺血性卒中死亡人数为69 327例,出血性卒中死亡人数为24 954例,其他未明确分类卒中为4 941例。平均每日全部卒中死亡人数为45例,缺血性卒中和出血性卒中每日死亡人数分别为32例和11例。平均每日死亡男性为26例,女性为20例。平均每日死亡 < 65岁者为7例,≥65岁者为38例。2014-2019年北京市日均温度为13.9 ℃,相对湿度为51.5%。空气污染物PM2.5、SO2、NO2、CO的日均浓度和O3最大8 h浓度的均数分别为63.4 μg/m3、10.0 μg/m3、44.2 μg/m3、1.0 mg/m3和103.1 μg/m3。见表 1。

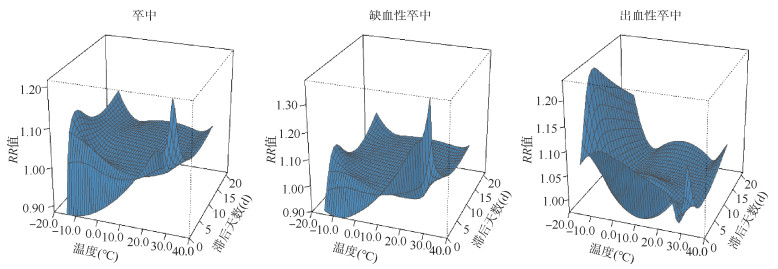

2. 气温对卒中死亡的影响:气温与卒中、缺血性卒中和出血性卒中死亡的非线性关系见图 1。对于缺血性卒中死亡,低温效应随着滞后天数的增加,其风险迅速增加,然后出现短暂下降后又逐渐升高,而高温效应在暴露当天较高,在滞后数天后趋于稳定。其最大效应出现在32.0 ℃暴露当天,RR值为1.38(95%CI:1.20~1.59)。对于出血性卒中死亡,低温暴露表现为死亡风险先迅速升高,滞后数天后达到最高值,然后其风险迅速下降,而高温暴露表现为死亡风险先降后升。其最大效应出现在-14.0 ℃滞后5 d时,RR值为1.24(95%CI:1.10~ 1.40)。

|

| 图 1 气温在不同滞后时间对卒中死亡影响的三维关联图 |

不同滞后天数时极低温、较低温、较高温和极高温对卒中死亡的累积风险见表 2。对于缺血性卒中死亡,与卒中死亡风险最小所对应的温度(MMT,10.0 ℃)相比,极低温(-6.2 ℃)存在滞后效应,在滞后0~21 d时达到最大效应(RR=1.26,95%CI:1.04~1.51);极高温的效应自滞后0~3 d出现,到滞后0~14 d时累积RR值为2.13(95%CI:1.72~2.62)。对于出血性卒中死亡,极低温对卒中死亡风险较持续,以MMT(28.0 ℃)为参照,极低温在滞后0~21 d达到最大效应(RR=2.14,95%CI:1.23~3.70),而极高温作用较为短暂,只在滞后0~3 d的累积效应有统计学意义(RR=1.14,95%CI:1.01~1.28)。

3. 性别和年龄的效应修饰作用:按照性别、年龄分层时气温对卒中死亡的影响见表 3。极低温对年龄≥65岁组的缺血性卒中和出血性卒中死亡风险均高于年龄 < 65岁组,但差异无统计学意义。极低温和较低温对女性的出血性卒中死亡效应高于男性,差异有统计学意义。极高温可增加不同性别和年龄组人群缺血性卒中死亡风险,且极高温对年龄 < 65岁组的缺血性卒中死亡风险效应高于年龄≥65岁组,差异有统计学意义。

本研究采用DLNM分析了2014-2019年北京市气温对卒中死亡的影响,研究发现气温和卒中死亡呈非线性关系,低温和高温均增加卒中死亡风险。同时,本研究发现气温对不同卒中类型的影响形式存在差异。极低温对缺血性卒中死亡的影响具有滞后性,在累积滞后0~14 d时开始显现出效应,而对出血性卒中滞后0~3 d即显现出效应。极高温对缺血性卒中死亡风险的影响较为持续,而对出血性卒中死亡风险的影响较短暂。

既往研究也报道了气温与卒中死亡风险之间的关系,但这些研究结果尚存在一定差异。我国一项研究纳入8个城市约12万例卒中死亡数据,该研究结果发现低温和高温均增加卒中死亡的风险[19],这与本研究结果一致。该研究中还发现低温效应较持续,而高温效应更短暂,仅发现在滞后0~3 d内的RR值有统计学意义。而本研究结果显示,极低温存在滞后效应,在累积滞后0~14 d时其效应才显现,而高温效应可持续存在。二者结果存在一定差异,可能是由于地区气候特征、统计方法等不同造成。本研究中使用MMT为参照,而上述研究中极低温和低温使用的是温度P25为参照,高温和极高温使用的是P75为参照。近期另一项来自我国山东省研究中,使用2013-2019年卒中死亡登记数据,该研究中同时分析了气温对缺血性和出血性卒中死亡的影响,发现低温均增加缺血性卒中死亡的风险且存在滞后效应,而高温效应较持续[20],这与本研究结果一致,同时该研究结果显示,极低温对出血性卒中同样也具有滞后效应,而本研究中发现极低温对出血性卒中死亡效应较持续。另一项来自我国上海地区的研究发现,高温未增加出血性卒中死亡的风险[8],本研究中也只发现高温对出血性卒中在滞后0~3 d出现累积效应。值得注意的是,本研究中出血性卒中样本量相对较少,气温对出血性卒中死亡的影响有待进一步研究。

分层分析发现,年龄≥65岁组是极低温对缺血性和出血性卒中死亡风险影响中的敏感人群。这与既往研究结果一致[7-8, 21]。老年人群由于其身体抵抗力差,且合并高血压、糖尿病等慢性基础疾病等原因,导致其对温度的敏感度更高。结果提示,应对低温对卒中的影响时,应更加关注年长者。

既往研究表明,低温和高温对卒中影响的机制不同。低温可激活交感神经系统和血管紧张素系统,导致血压升高、末梢血管收缩、血小板增多、血液黏稠度增加、血管内皮功能障碍等,从而导致心脑血管疾病的发生[22-24]。高温则可增加出汗、皮肤表面血流速度等,导致水分流失和脱水,伴随着血液浓缩和黏稠度增加,血栓风险增加,从而引起缺血性卒中的发生[23]。

本研究存在局限性。第一,本研究局限于北京市,由于不同地区的气候差异,结果推广到其他城市或地区受限;第二,由于本研究为观察性研究,尽管已校正了一系列的影响因素,但不可避免潜在混杂因素的影响;第三,暴露气温采用的是气象监测站点的数据,而未能考虑到室内温度的影响,可能会低估气温对结果的影响。

综上所述,本研究结果显示,低温对缺血性卒中死亡风险存在滞后性,而对出血性卒中死亡风险较持续,高温对缺血性卒中死亡风险作用较持续,而对出血性卒中死亡风险影响较短暂。本研究结果将有助于卒中防控措施的制定,为建立极端气温预警机制提供数据支持。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 张润华:数据整理、统计分析、论文撰写;王晶、李刚:数据整理、研究指导;刘改芬:研究指导、论文修改

| [1] |

Ma QF, Li R, Wang LJ, et al. Temporal trend and attributable risk factors of stroke burden in China, 1990-2019: An analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019[J]. Lancet Public Health, 2021, 6(12): e897-906. DOI:10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00228-0 |

| [2] |

Zhou MG, Wang HD, Zeng XY, et al. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017[J]. Lancet, 2019, 394(10204): 1145-1158. DOI:10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30427-1 |

| [3] |

Liu JW, Varghese BM, Hansen A, et al. Heat exposure and cardiovascular health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Lancet Planet Health, 2022, 6(6): e484-495. DOI:10.1016/S2542-5196(22)00117-6 |

| [4] |

Chen RJ, Yin P, Wang LJ, et al. Association between ambient temperature and mortality risk and burden: Time series study in 272 main Chinese cities[J]. BMJ, 2018, 363: k4306. DOI:10.1136/bmj.k4306 |

| [5] |

Tian YH, Liu H, Zhao ZL, et al. Association between ambient air pollution and daily hospital admissions for ischemic stroke: A nationwide time-series analysis[J]. PLoS Med, 2018, 15(10): e1002668. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002668 |

| [6] |

Vered S, Paz S, Negev M, et al. High ambient temperature in summer and risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack: a national study in Israel[J]. Environ Res, 2020, 187: 109678. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2020.109678 |

| [7] |

Zhou L, Chen K, Chen XD, et al. Heat and mortality for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke in 12 cities of Jiangsu province, China[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2017, 601-602: 271-277. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.05.169 |

| [8] |

陈亦晨, 陈华, 曲晓滨, 等. 日均气温对社区居民脑卒中死亡影响的时间序列研究[J]. 中国全科医学, 2022, 25(15): 1838-1844. DOI:10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2022.02.017 Chen YC, Chen H, Qu XB, et al. Impact of average daily temperature on stroke mortality in community: a time-series analysis[J]. Chinese General Practice, 2022, 25(15): 1838-1844. DOI:10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2022.02.017 |

| [9] |

Li L, Huang SL, Duan YR, et al. Effect of ambient temperature on stroke onset: a time-series analysis between 2003 and 2014 in Shenzhen, China[J]. Occup Environ Med, 2021, 78(5): 355-363. DOI:10.1136/oemed-2020-106985 |

| [10] |

曾韦霖, 李光春, 肖义泽, 等. 中国四城市温度对居民心脑血管疾病死亡影响的时间序列研究[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2012, 33(10): 1021-1025. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.10.006 Zeng WL, Li CG, Xiao YZ, et al. The impact of temperature on cardiovascular disease deaths in 4 cities, China: a time-series study[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2012, 33(10): 1021-1025. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.10.006 |

| [11] |

张云权, 宇传华, 鲍俊哲. 平均气温、寒潮和热浪对湖北省居民脑卒中死亡的影响[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2017, 38(4): 508-513. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.04.019 Zhang YQ, Yu CH, Bao JZ. Impact of daily mean temperature, cold spells, and heat waves on stroke mortality a multivariable Meta-analysis from 12 counties of Hubei province, China[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2017, 38(4): 508-513. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2017.04.019 |

| [12] |

Yang J, Yin P, Zhou MG, et al. The burden of stroke mortality attributable to cold and hot ambient temperatures: epidemiological evidence from China[J]. Environ Int, 2016, 92-93: 232-238. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2016.04.001 |

| [13] |

王晶, 刘庆萍, 王苹, 等. 2009-2018年北京市户籍居民死因监测分析[J]. 首都公共卫生, 2021, 15(2): 69-73. Wang J, Liu QP, Wang P, et al. Analysis of death causes monitoring among residents in Beijing, 2009-2018[J]. Cap J Public Health, 2021, 15(2): 69-73. |

| [14] |

Gasparrini A. Modeling exposure-lag-response associations with distributed lag non-linear models[J]. Stat Med, 2014, 33(5): 881-899. DOI:10.1002/sim.5963 |

| [15] |

Gasparrini A, Guo YM, Hashizume M, et al. Mortality risk attributable to high and low ambient temperature: a multicountry observational study[J]. Lancet, 2015, 386(9991): 369-375. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62114-0 |

| [16] |

Luo YX, Li HB, Huang FF, et al. The cold effect of ambient temperature on ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke hospital admissions: A large database study in Beijing, China between years 2013 and 2014-utilizing a distributed lag non-linear analysis[J]. Environ Pollut, 2018, 232: 90-96. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.021 |

| [17] |

He Y, Tang C, Liu X, et al. Effect modification of the association between diurnal temperature range and hospitalisations for ischaemic stroke by temperature in Hefei, China[J]. Public Health, 2021, 194: 208-215. DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.12.019 |

| [18] |

Kan HD, London SJ, Chen GH, et al. Season, sex, age, and education as modifiers of the effects of outdoor air pollution on daily mortality in Shanghai, China: The public health and air pollution in Asia (papa) study[J]. Environ Health Perspect, 2008, 116(9): 1183-1188. DOI:10.1289/ehp.10851 |

| [19] |

Chen R, Wang C, Meng X, et al. Both low and high temperature may increase the risk of stroke mortality[J]. Neurology, 2013, 81(12): 1064-1070. DOI:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a4a43c |

| [20] |

He FF, Wei J, Dong YL, et al. Associations of ambient temperature with mortality for ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and the modification effects of greenness in Shandong province, China[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2022, 851: 158046. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158046 |

| [21] |

Ravljen M, Bajrović F, Vavpotič D. A time series analysis of the relationship between ambient temperature and ischaemic stroke in the Ljubljana area: immediate, delayed and cumulative effects[J]. BMC Neurol, 2021, 21(1): 23. DOI:10.1186/s12883-021-02044-8 |

| [22] |

Kysely J, Pokorna L, Kyncl J, et al. Excess cardiovascular mortality associated with cold spells in the Czech republic[J]. BMC Public Health, 2009, 9: 19. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-9-19 |

| [23] |

Lavados PM, Olavarría VV, Hoffmeister L. Ambient temperature and stroke risk: evidence supporting a short-term effect at a population level from acute environmental exposures[J]. Stroke, 2018, 49(1): 255-261. DOI:10.1161/strokeaha.117.017838 |

| [24] |

Lichtman JH, Leifheit-Limson EC, Jones SB, et al. Average temperature, diurnal temperature variation, and stroke hospitalizations[J]. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis, 2016, 25(6): 1489-1494. DOI:10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.02.037 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44