文章信息

- 李春刚, 严双琴, 高国朋, 李小真, 樊诗琦, 蔡智玲, 曹慧, 陈茂林, 陶芳标.

- Li Chungang, Yan Shuangqin, Gao Guopeng, Li Xiaozhen, Fan Shiqi, Cai Zhiling, Cao Hui, Chen Maolin, Tao Fangbiao

- 母亲孕期饮食模式与儿童早期BMI变化轨迹关联的队列研究

- A cohort study of relationship between maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and early childhood BMI change trajectory

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(11): 1769-1775

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(11): 1769-1775

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230302-00116

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-03-02

2. 马鞍山市妇幼保健院, 马鞍山 243000

2. Maternal and Child Health Care Center of Ma'anshan, Ma'anshan 243000, China

健康与疾病的发育起源理论指出,胎儿期和儿童早期是发育的关键时期,母亲孕期合理饮食对促进胎儿和婴幼儿健康有重要意义[1]。饮食模式分析常用来评估整体饮食对健康的影响,与评估单一食物或营养物质相比,饮食模式分析更能反映实际饮食摄入情况[2]。研究发现孕期不健康饮食模式与新生儿早产和低出生体重有关[3],可能影响儿童早期生长速率[4]、增加儿童早期超重和肥胖风险[5-6],这些研究多为针对特定时点的调查,无法很好反映个体的生长发育变化过程,而BMI变化轨迹的纵向研究能有效评价婴幼儿个体的生长发育情况[7]。本研究依托马鞍山母婴健康队列(M-MIH),探讨母亲孕期饮食模式与儿童早期BMI变化轨迹的关联,从生命早期BMI变化轨迹视角为促进儿童健康发育提供科学依据。

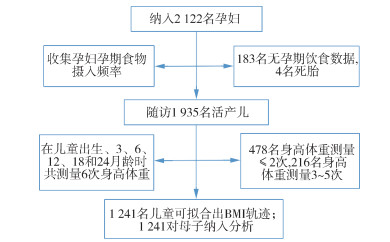

对象与方法1. 研究对象:来源于M-MIH,该队列是选择在马鞍山市妇幼保健院首次建册,常住市区范围并愿意在本院分娩的健康孕早期女性,共纳入2 122名孕妇,经排除后最终纳入1 241对母子为研究对象,纳入排除标准见图 1。本研究所有研究对象签署知情同意书。

|

| 图 1 研究对象纳入排除流程图 |

2. 调查内容与方法:

(1) 基本信息调查:通过孕产期母婴健康记录表收集母亲年龄、户籍地、孕前身高、体重、文化程度、工作性质、家庭人均月收入等数据。由新生儿分娩记录和随访获取分娩方式、儿童性别、胎龄、6月龄内患病情况、母乳喂养时间、出生体重和身高等信息。

(2) 饮食模式调查:选取能代表中国孕妇日常饮食习惯的食物条目共19项组成《孕妇饮食频率表问卷》[8],调查孕妇孕中期“一周”食物摄入频率。食物条目包括新鲜蔬菜水果、米及其制品、禽肉、猪肉、牛羊肉、油炸食品和饮料等。食物频率问卷(FFQ)是半定量调查问卷,食物条目提问方式:“您最近1周食用某食物频率是多少?”,食物频率得分标准:没吃/喝=1分,每周1~3次=2分,每周4~5次=3分,每周6~8次=4分,每周≥9次=5分。饮食模式以食物频率得分为基准构建,采用正交旋转的主成分分析法,将FFQ的食物条目全部纳入分析,食物条目因子载荷得分绝对值≥0.300和特征根 > 1.00作为纳入标准,建立母亲孕期饮食模式。

(3) 体格测量:分别在儿童出生、3、6、12、18和24月龄时进行随访体检,体检时测量并记录其身高和体重。采用仰卧法测量儿童身高,身高精确到0.1 cm,采用电子秤测量儿童体重,要求儿童穿单薄衣服,体重精确到0.1 kg。BMI=体重(kg)/身高(m)2,参照2006年WHO推荐儿童生长标准判定儿童消瘦(P25)、超重(P85)和肥胖(P95)[9]。

(4) 儿童BMI变化轨迹评估:在Stata 17.0软件中使用组基多轨迹模型来拟合儿童早期BMI变化轨迹[10],根据贝叶斯信息准则(BIC)和平均后验概率来选择拟合最优模型,BIC绝对值越小拟合效果越好,平均后验概率 > 0.7表示模型适合。

3. 统计学分析:采用EpiData 3.1软件建立数据库,在Stata 17.0软件中运用组基多轨迹模型拟合儿童BMI变化轨迹,使用SPSS 21.0软件进行统计学分析。计量资料用x±s表示;分类资料用构成比/率(%)表示。采用正交旋转的主成分分析确定饮食模式;采用χ2检验比较不同儿童BMI变化轨迹的人口学特征差异;以每类饮食模式食物频率得分P50为界值,将研究对象分为2组,即低水平组(≤P50)和高水平组(> P50),采用多分类logistic回归分析探讨母亲孕期不同饮食模式对儿童BMI变化轨迹的影响,以P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

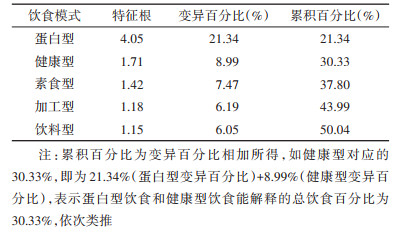

结果1. 饮食模式分类:本研究将19种食物分为5种饮食模式,第1种是蛋白型,主要包括禽肉、牛羊、鱼虾等水产品、猪肉、动物内脏和面及其制品;第2种是健康型,主要包括奶类及其制品、豆类及其制品、坚果类和蛋类;第3种是素食型,主要包括新鲜蔬菜、新鲜水果和米;第4种是加工型,主要包括腌制品、油炸食品和蒜类;第5种是饮料型,主要包括咖啡、可乐和茶。相关因子载荷得分见表 1。这5种饮食模式共解释了50.04%的总饮食变异,分别为21.34%、8.99%、7.47%、6.19%和6.05%。见表 2。

2. 儿童BMI变化轨迹特征:采用组基多轨迹模型拟合儿童BMI变化轨迹,偏瘦型变化轨迹占42.9%,此类儿童从出生到24月龄的平均BMI始终接近于消瘦界值(P25)。一般型变化轨迹占45.6%,此类儿童从出生到24月龄的平均BMI始终处于消瘦和超重界值之间(P25~P85),BMI值在正常生长标准内。偏胖型变化轨迹占11.5%,此类儿童出生时BMI尚处于正常范围内,但由于BMI增长过快,儿童在3~12月龄期间平均BMI始终高于肥胖界值(P95),在12~24月龄期间略有下降,但始终高于超重界值(P85),表现为偏胖的生长模式。见图 2。

|

| 图 2 根据组基多轨迹模型拟合的儿童BMI变化轨迹 |

3. 儿童早期不同BMI变化轨迹的一般人口学特征:母亲孕前BMI、母亲户籍地、母亲工作性质、分娩方式和儿童性别在不同儿童早期BMI变化轨迹间的分布差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),而母亲孕龄、母亲文化程度、家庭人均月收入、胎龄、3月龄喂养方式、6月龄内患病情况和纯母乳喂养情况在不同儿童早期BMI变化轨迹间的分布差异无统计学意义。见表 3。

4. 母亲孕期饮食模式和儿童早期BMI变化轨迹:蛋白型和饮料型饮食模式在儿童早期不同BMI变化轨迹间的分布差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),而其他3种饮食模式在儿童早期不同BMI变化轨迹间的分布差异无统计学意义。见表 4。调整潜在混杂因素后,分析结果显示,健康型和饮料型饮食模式与儿童早期BMI变化轨迹有统计学关联(P < 0.05)。偏瘦型与一般型变化轨迹相比,健康型饮食模式低水平组(OR=1.286,95%CI:1.002~1.651)儿童在生命早期更倾向于偏瘦型变化轨迹。偏胖型与一般型变化轨迹相比,饮料型饮食模式低水平组(OR=0.565,95%CI:0.342~0.935)儿童在生命早期更倾向于一般型变化轨迹。其他饮食模式与儿童早期BMI变化轨迹无统计学关联。见表 5。

随着生活水平和健康素养提高,人们日益关注孕期饮食健康。以往研究报告的饮食模式所代表的总饮食变异差异较大,中国上海市妊娠和后代健康队列研究发现2种饮食模式,共同解释饮食摄入量总变异的13.9%[11],挪威基于人群的妊娠队列研究确定的饮食模式解释总饮食变异的16.0%[12],而本研究共确定5种饮食模式,可解释总饮食变异的50.04%,与中国和美国妊娠队列研究结果相似,分别为40.5%[13]和52.9%[14]。其中蛋白型、健康型和素食型可归类为健康饮食模式,这与一些西方饮食模式相似,如“地中海饮食模式”[15]和“DASH饮食模式”[16],主要强调多吃蔬菜、水果、红肉、鱼、海鲜和豆类食物,有助于降低母婴疾病风险。此外,本研究发现有42.9%的儿童在生命早期表现为偏瘦型变化轨迹,这与Wang等[17]报告的低BMI变化轨迹组占比(59.0%)相似,主要原因可能是偏瘦型变化轨迹的总体BMI值还达不到消瘦的程度,即这条轨迹包括消瘦和正常偏瘦个体,因此其比例相对较高。

本研究评估母亲孕期饮食模式与儿童早期BMI变化轨迹的关联,类似研究报告较少,既往研究多探讨儿童特定时点生长情况,如美国前瞻性队列研究发现,母亲妊娠饮食质量与出生后早期婴儿肥胖呈负相关[18]。中国“沈阳出生队列研究”指出,母亲坚持“油炸食品-豆类-乳制品模式”与后代较低的超重和肥胖患病率相关[19],这与传统思维“油炸食品是肥胖发展的风险因素”相反[20],提示豆类和奶制品可能会扭转油炸食品的致肥作用。在本研究中,母亲孕期健康型和饮料型饮食模式与儿童早期BMI变化轨迹存在关联。其中健康型饮食模式包括蛋、豆、奶和坚果,这些食物是母亲孕期必需营养物质的重要来源之一,其低水平往往会影响儿童早期体重[2, 19]。另外,饮料型饮食模式包括咖啡、可乐和茶,有研究发现,以含糖饮料为代表的孕妇孕期饮食模式可能有助于儿童早期快速生长和增加后代肥胖风险[21]。美国一项前瞻性队列研究也发现,母亲在孕期和哺乳期过量摄入添加糖与儿童6月龄时体脂百分比呈正相关[22]。在一项微生物实验中,与不加糖饮食相比,高糖饮食的阴沟肠杆菌显著增加了线虫脂质积累[23],可能激活炎症巨噬细胞,损害结肠上皮通透性,诱导肥胖[24],阴沟肠杆菌在脂肪代谢中可能起致病作用[25]。从疾病预防角度来看,母亲孕期适量增加蛋、豆、奶和坚果等健康型饮食摄入和减少含糖饮料摄入是促进儿童早期健康成长的可控因素。

本研究存在局限性。第一,排除与纳入研究对象的基本特征存在差异,与排除的研究对象相比,纳入母亲户籍地更少位于农村、文化程度更高、工作性质以脑力工作为主,纳入儿童早产率更低、6月龄内患病率更低、纯母乳喂养至6月龄的比例更高,因此本研究可能会低估孕期不健康饮食模式对儿童早期生长发育的影响;第二,母亲孕期饮食模式会受社会经济水平影响,而本研究参与者只限于马鞍山市,因此参考本研究结果时,需结合当地经济发展水平和饮食特点。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 李春刚:数据整理、统计学分析、论文撰写;严双琴:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持;高国朋、蔡智玲、曹慧、陈茂林:采集数据、技术和材料支持;李小真、樊诗琦:采集数据、统计学分析;陶芳标:研究指导、论文修改、经费支持

| [1] |

Heindel JJ, Vandenberg LN. Developmental origins of health and disease: a paradigm for understanding disease cause and prevention[J]. Curr Opin Pediatr, 2015, 27(2): 248-253. DOI:10.1097/MOP.0000000000000191 |

| [2] |

Abdollahi S, Soltani S, de Souza RJ, et al. Associations between maternal dietary patterns and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies[J]. Adv Nutr, 2021, 12(4): 1332-1352. DOI:10.1093/advances/nmaa156 |

| [3] |

Chia AR, Chen LW, Lai JS, et al. Maternal dietary patterns and birth outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Adv Nutr, 2019, 10(4): 685-695. DOI:10.1093/advances/nmy123 |

| [4] |

Martin CL, Siega-Riz AM, Sotres-Alvarez D, et al. Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy are associated with child growth in the first 3 years of life[J]. J Nutr, 2016, 146(11): 2281-2288. DOI:10.3945/jn.116.234336 |

| [5] |

Stephenson J, Heslehurst N, Hall J, et al. Before the beginning: nutrition and lifestyle in the preconception period and its importance for future health[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10132): 1830-1841. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30311-8 |

| [6] |

Dalrymple KV, Vogel C, Godfrey KM, et al. Longitudinal dietary trajectories from preconception to mid-childhood in women and children in the Southampton Women's Survey and their relation to offspring adiposity: a group-based trajectory modelling approach[J]. Int J Obes, 2022, 46(4): 758-766. DOI:10.1038/s41366-021-01047-2 |

| [7] |

Mebrahtu TF, Feltbower RG, Petherick ES, et al. Growth patterns of white British and Pakistani children in the Born in Bradford cohort: a latent growth modelling approach[J]. J Epidemiol Community Health, 2015, 69(4): 368-373. DOI:10.1136/jech-2014-204571 |

| [8] |

邢秀雅. 孕妇饮食模式及其与妊娠结局关联的队列研究[D]. 合肥: 安徽医科大学, 2010. DOI: 10.7666/d.D128881. Xing XY. Maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes: a population-based cohort study[D]. Hefei: Anhui Medical University, 2010. DOI: 10.7666/d.D128881. |

| [9] |

WHO (World Health Organization). WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight- for-length, weight-for-height and body mass index-for- age: methods and development[EB/OL]. (2006-11-11)[2022-12-25]. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/51510/retrieve.

|

| [10] |

Nagin DS, Jones BL, Passos VL, et al. Group-based multi- trajectory modeling[J]. Stat Methods Med Res, 2018, 27(7): 2015-2023. DOI:10.1177/0962280216673085 |

| [11] |

de Seymour JV, Beck KL, Conlon CA, et al. An investigation of the relationship between dietary patterns in early pregnancy and maternal/infant health outcomes in a Chinese cohort[J]. Front Nutr, 2022, 9: 775557. DOI:10.3389/fnut.2022.775557 |

| [12] |

Englund-Ögge L, Brantsæter AL, Sengpiel V, et al. Maternal dietary patterns and preterm delivery: results from large prospective cohort study[J]. BMJ, 2014, 348: g1446. DOI:10.1136/bmj.g1446 |

| [13] |

Wang ZY, Zhao SL, Cui XY, et al. Effects of dietary patterns during pregnancy on preterm birth: a birth cohort study in Shanghai[J]. Nutrients, 2021, 13(7): 2367. DOI:10.3390/nu13072367 |

| [14] |

Martin CL, Sotres-Alvarez D, Siega-Riz AM. Maternal dietary patterns during the second trimester are associated with preterm birth[J]. J Nutr, 2015, 145(8): 1857-1864. DOI:10.3945/jn.115.212019 |

| [15] |

Makarem N, Chau K, Miller EC, et al. Association of a mediterranean diet pattern with adverse pregnancy outcomes among US women[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2022, 5(12): e2248165. DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.48165 |

| [16] |

Polanska K, Kaluzny P, Aubert AM, et al. Dietary quality and dietary inflammatory potential during pregnancy and offspring emotional and behavioral symptoms in childhood: an individual participant data meta-analysis of four European cohorts[J]. Biol Psychiatry, 2021, 89(6): 550-559. DOI:10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.10.008 |

| [17] |

Wang XH, Martinez MP, Chow T, et al. BMI growth trajectory from ages 2 to 6 years and its association with maternal obesity, diabetes during pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and breastfeeding[J]. Pediatr Obes, 2020, 15(2): e12579. DOI:10.1111/ijpo.12579 |

| [18] |

Tahir MJ, Haapala JL, Foster LP, et al. Higher maternal diet quality during pregnancy and lactation is associated with lower infant weight-for-length, body fat percent, and fat mass in early postnatal life[J]. Nutrients, 2019, 11(3): 632. DOI:10.3390/nu11030632 |

| [19] |

Hu JJ, Aris IM, Lin PID, et al. Association of maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy and offspring weight status across infancy: results from a prospective birth cohort in China[J]. Nutrients, 2021, 13(6): 2040. DOI:10.3390/nu13062040 |

| [20] |

Sun YB, Liu BY, Snetselaar LG, et al. Association of fried food consumption with all cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality: prospective cohort study[J]. BMJ, 2019, 364: k5420. DOI:10.1136/bmj.k5420 |

| [21] |

Hu ZS, Tylavsky FA, Kocak M, et al. Effects of maternal dietary patterns during pregnancy on early childhood growth trajectories and obesity risk: the CANDLE study[J]. Nutrients, 2020, 12(2): 465. DOI:10.3390/nu12020465 |

| [22] |

Nagel EM, Jacobs D, Johnson KE, et al. Maternal dietary intake of total fat, saturated fat, and added sugar is associated with infant adiposity and weight status at 6 mo of age[J]. J Nutr, 2021, 151(8): 2353-2360. DOI:10.1093/jn/nxab101 |

| [23] |

Gu MK, Werlinger P, Cho JH, et al. Lactobacillus pentosus MJM60383 inhibits lipid accumulation in Caenorhabditis elegans induced by Enterobacter cloacae and glucose[J]. Int J Mol Sci, 2022, 24(1): 280. DOI:10.3390/ijms24010280 |

| [24] |

Lim SM, Jeong JJ, Woo KH, et al. Lactobacillus sakei OK67 ameliorates high-fat diet-induced blood glucose intolerance and obesity in mice by inhibiting gut microbiota lipopolysaccharide production and inducing colon tight junction protein expression[J]. Nutr Res, 2016, 36(4): 337-348. DOI:10.1016/j.nutres.2015.12.001 |

| [25] |

Fei N, Zhao LP. An opportunistic pathogen isolated from the gut of an obese human causes obesity in germfree mice[J]. ISME J, 2013, 7(4): 880-884. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2012.153 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44