文章信息

- 徐慧雯, 陈毓铭, 杨洲, 胡永华, 许蓓蓓.

- Xu Huiwen, Chen Yuming, Yang Zhou, Hu Yonghua, Xu Beibei

- 中国老年人心血管代谢性共病与握力和步速关系的队列研究

- Associations of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with grip strength and gait speed among older Chinese adults

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(8): 1183-1189

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(8): 1183-1189

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20230108-00015

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2023-01-08

2. 北京大学医学信息学中心, 北京 100191;

3. 北京大学医学部老年健康医学中心, 北京 100191

2. Peking University Medical Informatics Center, Beijing 100191, China;

3. Center for Health Aging, Peking University Health Science Center, Beijing 100191, China

心血管代谢性共病指同一个体同时患有≥2种的心血管代谢性疾病,如高血压、糖尿病等[1]。随着社会老龄化的日益加剧,心血管代谢性共病患病率迅速增加[2]。一项基于100万中国成年人纵向队列研究显示,中国人群心血管代谢性共病患病率为5.94%,在5年内增加了1倍以上[3]。另一项基于中国健康与退休追踪调查(China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study,CHARLS)数据显示,中国≥45岁的中老年人心血管代谢性共病患病率为24.5%[4]。心血管代谢性共病会增加老年人死亡、痴呆、认知功能下降、身体功能下降等不良健康结局的风险,已成为我国日益严峻的挑战之一[1-2, 5-6]。握力和步速可反映老年人肌肉力量,是衡量老年人身体功能表现的客观指标,具有简便性及可靠性[7-8]。握力与步速已被证明可以准确预测老年人死亡率、残疾与住院率[9-11]。通过握力与步速测量心血管代谢性共病患者的身体功能表现,可评估心血管代谢性共病严重程度,对心血管代谢性共病进行早期干预,避免不良健康结局的发生[6]。已有研究发现,单一的心血管代谢性疾病与较差的身体功能表现有关[12-13]。本研究利用CHARLS数据,分析心血管代谢性共病与握力和步速之间的关系。

资料与方法1. 资料来源:来源于CHARLS,该项目由北京大学开展,主要针对≥45岁的中老年人。CHARLS采用多阶段概率抽样,于2011和2012年进行基线调查,每两年进行一次随访调查,调查区域覆盖全国28个省份150个县级单位的450个村级单位,是全国具有代表性的中老年人群健康调查研究之一[14]。由于2018年未采集调查对象的体格检查指标,本研究使用2011、2013、2015年数据进行分析。本研究纳入9 106名基线≥60岁的调查对象,排除在基线时心血管代谢性疾病信息缺失(n=67)、随访调查时握力或步速信息缺失(n=7)、无随访记录(n=2 592)样本,剩余6 440名研究对象,最终纳入测量握力的研究对象6 357名,测量步速的研究对象6 250名。

2. 研究内容:心血管代谢性疾病包括高血压、糖尿病(包括糖耐量异常和FPG升高)、血脂异常(高血脂或低血脂)、脑卒中和心脏病(如心肌梗死、冠心病、心绞痛、充血性心力衰竭和其他心脏病)。本研究通过询问研究对象是否患有相应的疾病定义糖尿病、血脂异常、脑卒中和心脏病。高血压定义为3次测量的SBP平均值> 140 mmHg(1 mmHg=0.133 kPa)或DBP平均值> 90 mmHg或自报患有高血压。心血管代谢性共病定义为同一个体同时患有≥2种心血管代谢性疾病。

采用秒表记录研究对象以正常速度行走2.5 m所用的时间,步速计算为行走距离与时间的比值,取2次测量的平均值作为最终步速[15]。采用悦健WL-1000握力器评估研究对象的握力。每只手测量2次,选取最大值作为握力值,将握力值(kg)除以研究对象的体重(kg)以对握力值进行标准化[16]。

其他变量包括年龄、性别、婚姻状况、居住地区(农村、城市)、文化程度、吸烟状况、饮酒状况、BMI、职业。婚姻状况分为已婚(包括同居)和非已婚(包括单身/离异/分居/丧偶)。询问研究对象是否吸烟以及是否戒烟,如自报从未吸过烟,则定义为从不吸烟;如自报吸过烟但现在已戒烟,则定义为以前吸烟;如自报吸过烟并且现在仍然吸烟,则定义为现在吸烟。询问研究对象在过去的一年中以及以前是否饮酒以及饮酒频率,如自报在过去的一年中饮酒频率大于每月1次,定义为现在饮酒;如自报在过去的一年中饮酒频率每月少于1次或者不饮酒,但以前的饮酒频率大于每月1次,则定义为以前饮酒;否则定义为从不饮酒。文化程度分为小学以下、小学、初中、高中及以上。BMI=体重(kg)/身高(m)2,并分为4类(< 18.5、18.5~、23.0~、≥27.5 kg/m2)[17]。根据研究对象1年内是否有10 d进行农业活动以及上周是否进行非农业工作≥1 h定义职业,分为农业、非农业、农业及非农业、未工作。

3. 统计学分析:采用SAS 9.4软件进行数据分析。符合正态分布的计量资料采用x±s表示,不符合正态分布的计量资料采用M(Q1,Q3)表示,计数资料采用频数及构成比进行描述,计数资料的组间比较采用χ2检验。采用广义估计方程分析心血管代谢性疾病数量及组合与握力和步速之间的关系,并估计标准化握力与步速预测值,选取Identity作为连接函数,采用可交换作业相关矩阵。其中,基线心血管代谢性疾病数量及组合为暴露变量(分类变量),随访过程中步速与握力为结局变量(连续变量),调整基线时的年龄、性别、婚姻状况、居住地区、文化程度、吸烟状况、饮酒状况、BMI、职业。此外,本研究利用广义估计方程模型,将基线心血管代谢性疾病数量作为连续变量,对标准化握力预测值与步速预测值随心血管代谢性疾病数量的变化进行趋势性检验。由于2013年CHARLS未收集血液数据,本研究选取2011以及2015年数据,结合血液样本信息重新定义糖尿病及血脂异常进行敏感性分析。血脂异常定义为血清TC≥6.22 mmol/L(240 mg/dl)、TG≥2.26 mmol/L(200 mg/dl)、HDL-C < 1.04 mmol/L(40 mg/dl)、LDL-C≥4.14 mmol/L(160 mg/dl)或自报患有血脂异常,糖尿病定义为FPG≥7.0 mmol/L(≥126 mg/dl)、非FPG≥11.1 mmol/L(≥200 mg/dl)、糖化血红蛋白≥6.5%或自报患有糖尿病[18-19]。为了确保模型收敛,本研究剔除患病率 < 0.1%的心血管代谢性疾病组合。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

结果1. 基线特征:本研究纳入测量握力的研究对象6 357名,标准化握力M(Q1,Q3)为0.53(0.42,0.64),测量步速的研究对象6 250名,步速为(0.54±0.17)m/s。在测量握力的研究对象中,年龄为(67.6±6.3)岁,男性3 208名(50.5%),患有高血压、心脏病、脑卒中、血脂异常、糖尿病分别为3 011名(47.4%)、948名(14.9%)、189名(3.0%)、634名(10.0%)、426名(6.7%)。在测量步速的研究对象中,年龄为(67.5±6.3)岁,男性3 151名(50.4%),患有高血压、心脏病、脑卒中、血脂异常、糖尿病分别为2 941名(47.1%)、923名(14.8%)、177名(2.8%)、613名(9.8%)、413名(6.6%)。与纳入人群相比,排除人群年龄较大、非已婚状态、居住在城市、BMI为18.5~22.9 kg/m2、患有心脏病、脑卒中、血脂异常和糖尿病所占比例较大(均P < 0.05),现在吸烟和现在饮酒所占比例较小(均P < 0.001)。见表 1,2。

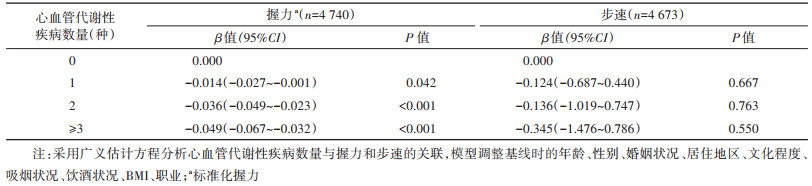

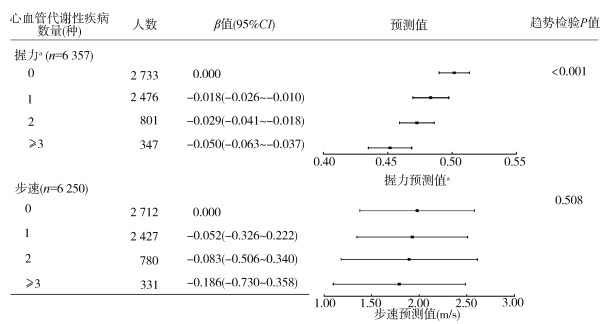

2. 心血管代谢性疾病数量与握力和步速的关系:与未患心血管代谢性疾病组相比,患有1种(β=-0.018,95%CI:-0.026~-0.010)、2种(β=-0.029,95%CI:-0.041~-0.018)、≥3种(β=-0.050,95%CI:-0.063~-0.037)心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象握力下降的风险增加。未患心血管代谢性疾病以及患有1、2、≥3种心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象标准化握力预测值逐渐下降(趋势检验P < 0.001),分别为0.50(95%CI:0.49~0.51)、0.48(95%CI:0.47~0.50)、0.47(95%CI:0.46~0.49)和0.45(95%CI:0.43~0.47)。心血管代谢性疾病数量(1种:β=-0.052,95%CI:-0.326~0.222;2种:β=-0.083,95%CI:-0.506~0.340;≥3种:β=-0.186,95%CI:-0.730~0.358)与步速的关联无统计学意义。未患心血管代谢性疾病以及患有1、2、≥3种心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象步速预测值分别为1.98(95%CI:1.38~2.58)、1.93(95%CI:1.34~2.51)、1.89(95%CI:1.18~2.61)和1.79(95%CI:1.10~2.48)m/s。见图 1。结合血液样本信息定义糖尿病与血脂异常的敏感性分析中,纳入测量握力的研究对象4 740名,测量步速的研究对象4 673名,研究结果与主要分析相似。见表 3。

|

| 注:采用广义估计方程分析心血管代谢性疾病数量与握力和步速的关联,模型调整基线时的年龄、性别、婚姻状况、居住地区、文化程度、吸烟状况、饮酒状况、BMI、职业;a标准化握力 图 1 心血管代谢性疾病数量与握力和步速的关联 |

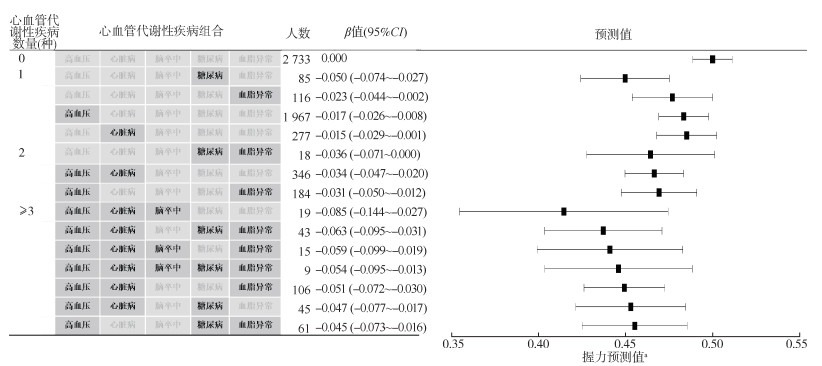

3. 心血管代谢性疾病组合与握力和步速的关系:与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,仅患有糖尿病(β=-0.050,95%CI:-0.074~-0.027)、血脂异常(β=-0.023,95%CI:-0.044~-0.002)、高血压(β=-0.017,95%CI:-0.026~-0.008)、心脏病(β=-0.015,95%CI:-0.029~-0.001)的研究对象握力下降的风险增加。在患有2种心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象中,与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,糖尿病和血脂异常(β=-0.036,95%CI:-0.071~0.000)、高血压和心脏病(β=-0.034,95%CI:-0.047~-0.020)、高血压和血脂异常(β=-0.031,95%CI:-0.050~-0.012)握力下降的风险增加。在患有≥3种心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象中,与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,高血压、心脏病和脑卒中(β=-0.085,95%CI:-0.144~-0.027)、高血压、心脏病、糖尿病和血脂异常(β=-0.063,95%CI:-0.095~-0.031)、高血压、心脏病、脑卒中和血脂异常(β=-0.059,95%CI:-0.099~-0.019)等组合握力下降的风险增加。见图 2。

|

| 注:模型调整基线时的年龄、性别、婚姻状况、居住地区、文化程度、吸烟状况、饮酒状况、BMI、职业;心血管代谢性疾病组合中所包含的疾病以深灰色背景及黑色字体表示,浅灰色背景及字体代表心血管代谢性疾病组合中未包括该疾病;a标准化握力 图 2 心血管代谢性疾病组合与握力的关联 |

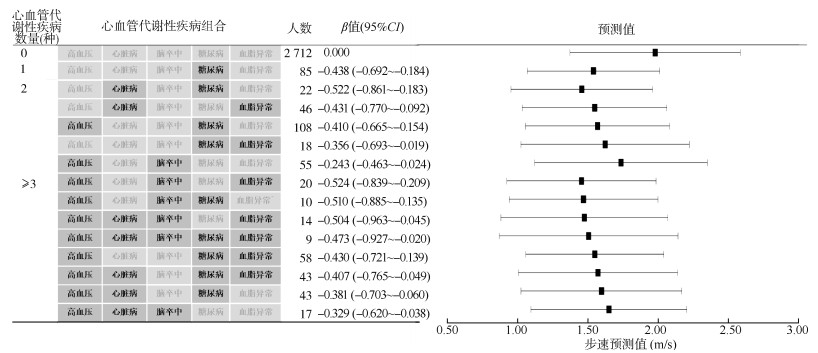

与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,仅患有糖尿病(β=-0.438,95%CI:-0.692~-0.184)的研究对象步速下降的风险增加。在患有2种心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象中,与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,心脏病和糖尿病(β=-0.522,95%CI:-0.861~-0.183)、心脏病和血脂异常(β=-0.431,95%CI:-0.770~-0.092)、高血压和糖尿病(β=-0.410,95%CI:-0.665~-0.154)等组合步速下降的风险增加。在患有≥3种心血管代谢性疾病的研究对象中,与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,高血压、脑卒中和血脂异常(β=-0.524,95%CI:-0.839~-0.209)、高血压、脑卒中和糖尿病(β=-0.510,95%CI:-0.885~-0.135)、高血压、心脏病、脑卒中和血脂异常(β=-0.504,95%CI:-0.963~-0.045)等组合步速下降的风险增加。见图 3。

|

| 注:采用广义估计方程分析心血管代谢性疾病组合与握力和步速的关联,模型调整基线时的年龄、性别、婚姻状况、居住地区、文化程度、吸烟状况、饮酒状况、BMI、职业;心血管代谢性疾病组合中所包含疾病以深灰色背景及黑色字体表示,浅灰色背景及字体代表心血管代谢性疾病组合中未包括该疾病 图 3 心血管代谢性疾病组合与步速的关联 |

本研究基于中国老年人全国代表性数据探索心血管代谢性共病与老年人步速和握力之间的关系。研究结果发现,随着心血管代谢性疾病数量的增加,≥60岁的老年人握力下降的风险逐渐增加。具有较高的握力降低、步速减慢风险的心血管代谢性疾病组合大多包含糖尿病。

与既往研究一致,本研究发现患有心血管代谢性疾病数量越多,握力下降的风险越大[6, 20-21]。未发现心血管代谢性疾病数量与步速之间存在统计学关联。既往研究显示,老年人步速下降幅度达到0.05 m/s即有临床意义,达到0.1 m/s即发生显著的改变[22]。一项纳入3万名以上≥65岁老年人的研究发现,步速每降低0.1 m/s,老年人生存率降低12%[23]。本研究结果显示,与未患心血管代谢性疾病相比,患有≥3种心血管代谢性疾病的老年人步速预测值降低了0.19 m/s,已具有显著的临床意义。心血管代谢性共病与握力和步速之间的关系可能与营养耗竭、炎症、氧化应激以及缺乏运动等机制有关[6, 24-25]。此外,随着我国心血管代谢性共病负担的不断增加,心血管代谢性共病患者的多重用药现象日益严重,部分心血管代谢性共病患者可能会服用多种药物,药物相互作用及药物疾病相互作用的风险增加,进而导致身体状况恶化[26-28]。

心血管代谢性疾病组合与握力和步速关系的研究结果显示,具有较高的握力降低、步速减慢风险的心血管代谢性疾病组合大多包含糖尿病。既往研究也发现糖尿病会降低老年人握力与步速[29-30]。糖尿病患者可能会出现下肢肌肉萎缩、无力及运动不协调,导致患者步速降低[29]。糖尿病与握力之间的关系还可能与高水平葡萄糖变异、腺嘌呤核苷三磷酸减少、活性氧增加、肌纤维数量减少等机制有关[30]。应重点关注糖尿病,特别是伴随其他心血管代谢性疾病的患者,采取及时的干预措施,以预防不良健康结局的发生。

本研究存在局限性。首先,心血管代谢性疾病通过自报方式收集,可能存在回忆偏倚;其次,部分心血管代谢性疾病组合样本量较小,无法探索其与握力和步速的实际关联;最后,本研究测量步速采用的2.5 m距离较短,步速变异性可能较大,不能真实反映老年人正常步速[31]。

综上所述,心血管代谢性疾病共病与老年人握力和步速相关,握力和步速可作为简单、可靠的测量指标,监测老年人心血管代谢性疾病共病的严重程度,以预防更加严重的不良健康结局发生。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 徐慧雯:酝酿和设计实验、实施研究、分析/解释数据、撰写论文、统计分析;陈毓铭、杨洲、胡永华:论文审阅;许蓓蓓:酝酿和设计实验、解释数据、论文审阅、经费支持

| [1] |

Dove A, Guo J, Marseglia A, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity and incident dementia: the Swedish twin registry[J]. Eur Heart J, 2023, 44(7): 573-582. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehac744 |

| [2] |

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Association of cardiometabolic multimorbidity with mortality[J]. JAMA, 2015, 314(1): 52-60. DOI:10.1001/jama.2015.7008 |

| [3] |

Zhang DD, Tang X, Shen P, et al. Multimorbidity of cardiometabolic diseases: prevalence and risk for mortality from one million Chinese adults in a longitudinal cohort study[J]. BMJ Open, 2019, 9(3): e024476. DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024476 |

| [4] |

Huang ZT, Luo Y, Han L, et al. Patterns of cardiometabolic multimorbidity and the risk of depressive symptoms in a longitudinal cohort of middle-aged and older Chinese[J]. J Affect Disord, 2022, 301: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2022.01.030 |

| [5] |

Dove A, Marseglia A, Shang Y, et al. Cardiometabolic multimorbidity accelerates cognitive decline and dementia progression[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2023, 19(3): 821-830. DOI:10.1002/alz.12708 |

| [6] |

Yao SS, Meng XF, Cao GY, et al. Associations between multimorbidity and physical performance in older Chinese adults[J]. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 2020, 17(12): 4546. DOI:10.3390/ijerph17124546 |

| [7] |

Mijnarends DM, Meijers JMM, Halfens RJG, et al. Validity and reliability of tools to measure muscle mass, strength, and physical performance in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2013, 14(3): 170-178. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.009 |

| [8] |

Stevens PJ, Syddall HE, Patel HP, et al. Is grip strength a good marker of physical performance among community-dwelling older people?[J]. J Nutr Health Aging, 2012, 16(9): 769-774. DOI:10.1007/s12603-012-0388-2 |

| [9] |

Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB, et al. Added value of physical performance measures in predicting adverse health-related events: results from the Health, Aging And Body Composition Study[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2009, 57(2): 251-259. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02126.x |

| [10] |

Cesari M, Kritchevsky SB, Penninx BWHJ, et al. Prognostic value of usual gait speed in well-functioning older people-results from the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2005, 53(10): 1675-1680. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x |

| [11] |

Stessman J, Rottenberg Y, Fischer M, et al. Handgrip strength in old and very old adults: mood, cognition, function, and mortality[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2017, 65(3): 526-532. DOI:10.1111/jgs.14509 |

| [12] |

Guo XX, Matousek M, Sundh V, et al. Motor performance in relation to age, anthropometric characteristics, and serum lipids in women[J]. J Gerontol: Ser A, 2002, 57(1): M37-44. DOI:10.1093/gerona/57.1.m37 |

| [13] |

Hao G, Chen HY, Ying YT, et al. The relative handgrip strength and risk of cardiometabolic disorders: a prospective study[J]. Front Physiol, 2020, 11: 719. DOI:10.3389/fphys.2020.00719 |

| [14] |

Zhao YH, Hu YS, Smith JP, et al. Cohort profile: the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS)[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2014, 43(1): 61-68. DOI:10.1093/ije/dys203 |

| [15] |

Hooghiemstra AM, Ramakers IHGB, Sistermans N, et al. Gait speed and grip strength reflect cognitive impairment and are modestly related to incident cognitive decline in memory clinic patients with subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment: findings from the 4C study[J]. J Gerontol: Ser A, 2017, 72(6): 846-854. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glx003 |

| [16] |

Peterson MD, Duchowny K, Meng QQ, et al. Low normalized grip strength is a biomarker for cardiometabolic disease and physical disabilities among U. S. and Chinese adults[J]. J Gerontol: Ser A, 2017, 72(11): 1525-1531. DOI:10.1093/gerona/glx031 |

| [17] |

WHO Expert Consultation. Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies[J]. Lancet, 2004, 363(9403): 157-163. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15268-3 |

| [18] |

中国成人血脂异常防治指南制订联合委员会. 中国成人血脂异常防治指南[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2007, 35(5): 390-419. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0253-3758.2007.05.003 Joint Committee for Developing Chinese Guidelines on Prevention and Treatment of Dyslipidemia in Adults. Chinese guidelines on prevention and treatment of dyslipidemia in adults[J]. Chin J Cardiol, 2007, 35(5): 390-419. DOI:10.3760/j.issn:0253-3758.2007.05.003 |

| [19] |

American Diabetes Association. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes[J]. Diabetes Care, 2016, 39(Suppl 1): S13-22. DOI:10.2337/dc16-S005 |

| [20] |

Volaklis KA, Halle M, Thorand B, et al. Handgrip strength is inversely and independently associated with multimorbidity among older women: Results from the KORA-Age study[J]. Eur J Intern Med, 2016, 31: 35-40. DOI:10.1016/j.ejim.2016.04.001 |

| [21] |

Yorke AM, Curtis AB, Shoemaker M, et al. The impact of multimorbidity on grip strength in adults age 50 and older: data from the health and retirement survey (HRS)[J]. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2017, 72: 164-168. DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2017.05.011 |

| [22] |

Perera S, Mody SH, Woodman RC, et al. Meaningful change and responsiveness in common physical performance measures in older adults[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2006, 54(5): 743-749. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00701.x |

| [23] |

Aubert CE, Kabeto M, Kumar N, et al. Multimorbidity and long-term disability and physical functioning decline in middle-aged and older Americans: an observational study[J]. BMC Geriatr, 2022, 22(1): 910. DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-03548-9 |

| [24] |

Gacitua T, Karachon L, Romero E, et al. Effects of resistance training on oxidative stress-related biomarkers in metabolic diseases: a review[J]. Sport Sci Health, 2018, 14(1): 1-7. DOI:10.1007/s11332-017-0402-5 |

| [25] |

Howard C, Ferrucci L, Sun K, et al. Oxidative protein damage is associated with poor grip strength among older women living in the community[J]. J Appl Physiol, 2007, 103(1): 17-20. DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.00133.2007 |

| [26] |

Calderón-Larrañaga A, Vetrano DL, Ferrucci L, et al. Multimorbidity and functional impairment-bidirectional interplay, synergistic effects and common pathways[J]. J Intern Med, 2019, 285(3): 255-271. DOI:10.1111/joim.12843 |

| [27] |

张波, 闫雪莲, 王秋梅, 等. 重视老年人多重用药问题[J]. 中华老年医学杂志, 2012, 31(2): 171-174. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-9026.2012.02.024 Zhang B, Yan XL, Wang QM, et al. Attaching great importance to polypharmacy in elderly patients[J]. Chin J Geriatr, 2012, 31(2): 171-174. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-9026.2012.02.024 |

| [28] |

Cheung JTK, Yu R, Woo J. Is polypharmacy beneficial or detrimental for older adults with cardiometabolic multimorbidity? Pooled analysis of studies from Hong Kong and Europe[J]. Fam Pract, 2020, 37(6): 793-800. DOI:10.1093/fampra/cmaa062 |

| [29] |

Volpato S, Bianchi L, Lauretani F, et al. Role of muscle mass and muscle quality in the association between diabetes and gait speed[J]. Diabetes Care, 2012, 35(8): 1672-1679. DOI:10.2337/dc11-2202 |

| [30] |

Turner LV, MacDonald MJ, Riddell MC, et al. Decreased diastolic blood pressure and average grip strength in adults with type 1 diabetes compared with controls: an analysis of data from the Canadian longitudinal study on aging[J]. Can J Diabetes, 2022, 46(8): 789-796. DOI:10.1016/j.jcjd.2022.05.005 |

| [31] |

Lindemann U, Najafi B, Zijlstra W, et al. Distance to achieve steady state walking speed in frail elderly persons[J]. Gait Posture, 2008, 27(1): 91-96. DOI:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.02.005 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44