文章信息

- 戎猛, 袁满琼, 方亚.

- Rong Meng, Yuan Manqiong, Fang Ya

- 阿尔茨海默病发病年龄影响因素研究

- A study on factors associated with age of Alzheimer's disease onset

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(7): 1068-1072

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(7): 1068-1072

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20221007-00861

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-10-07

在人口老龄化形势严峻的当下,阿尔茨海默病(AD)成为一项日益严重的全球健康问题。WHO 2022年痴呆实况报道显示,全球现有痴呆患者已超过5 500万,预计到2050年将升至1.39亿,其中60%~70%为AD患者[1]。AD属于年龄依赖性疾病,其发病率随着年龄的增长而上升,65岁以上的发病率为1%~5%,85岁以上则高达20%~40%[2]。有研究表明AD发病年龄越早,认知功能恶化越快[3-4]。AD患者从症状出现到死亡的时间也受发病年龄影响,发病年龄越大,其生存时间越短[5-6]。尽管AD不可逆,且目前尚无治愈的方法,但大量研究证实若能在AD发病前进行干预,可减缓认知功能下降的速度[7-9]。本研究旨在了解AD发病年龄特征及其影响因素,为AD的早发现、早诊断、早治疗提供科学依据。

对象与方法1. 研究对象: 数据来源于2005-2022年阿尔茨海默病神经影像学倡议(ADNI)的数据库(https://adni.loni.usc.edu/)。ADNI是一项纵向多中心研究,截至2022年已招募年龄55~90岁的研究对象1 800余名,主要来自于美国和加拿大的63个地区。根据诊断标准,研究对象认知状态被划分为认知功能正常(CN)、轻度认知功能障碍(MCI)和AD。ADNI包括ADNI-1、ADNI-GO、ADNI-2和ADNI-3四个阶段研究,除了ADNI-3中CN者在基线随访后每2年随访一次,其他研究对象均每隔6个月或12个月随访一次。诊断标准和随访实施办法见ADNI数据库操作手册(https://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/ADNI_GeneralProceduresManual.pdf)。本研究选取基线认知状态为CN或MCI,且随访期间发生AD者共405名为研究对象,随访间隔平均为6.6个月。

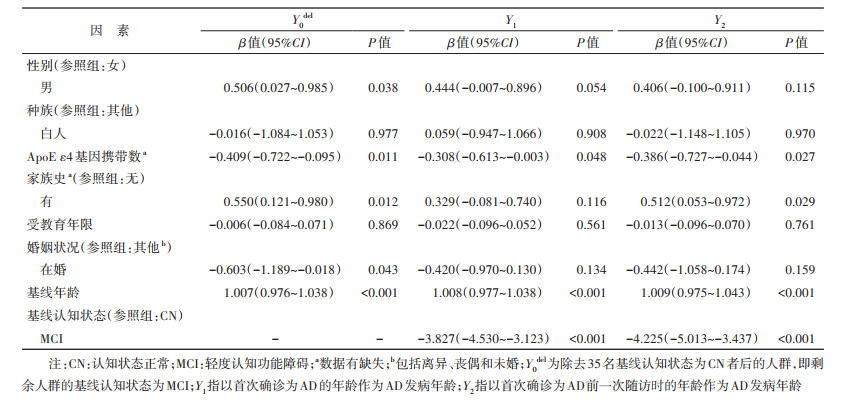

2. AD发病年龄: 以首次确诊为AD的年龄与其前一次随访时年龄的平均值作为AD发病年龄(Y0),如某位患者随访期间首次确诊为AD的年龄为75.00岁,其前一次随访是在6个月前(即74.50岁),则认为该对象的AD发病年龄为74.75岁。

3. 敏感性分析: 由于ADNI的随访间隔最短为6个月,无法获取精准的AD发病年龄。为检验结果的稳健性,分别以首次确诊为AD的年龄(Y1)和前一次随访时的年龄(Y2)作为AD发病年龄进行影响因素分析。此外,本研究进一步剔除基线状态为CN者35名,仅对基线认知状态为MCI者的AD发病年龄(Y0del)进行影响因素分析。

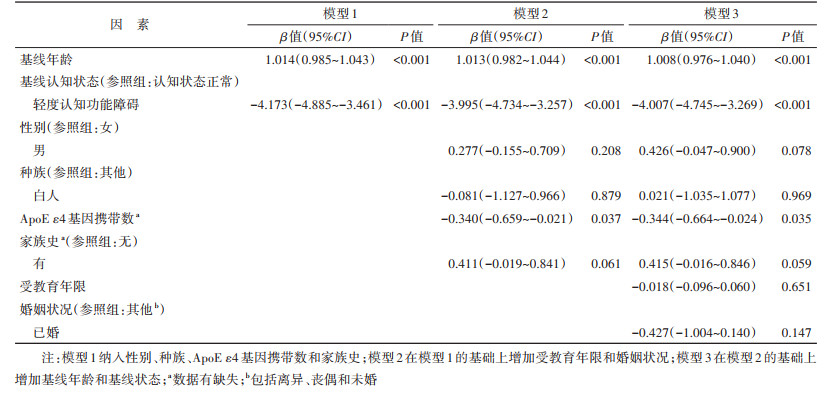

4. 统计学分析: 采用SPSS 23.0软件进行统计学分析。连续性变量采用x±s描述,分类变量采用构成比描述。采用独立样本t检验或单因素方差分析,比较不同特征下的AD发病年龄差异。进一步建立3个多元线性回归模型探索AD发病年龄的影响因素,其中模型1纳入性别、种族、ApoE ε4基因携带数和家族史;模型2在模型1的基础上增加受教育年限和婚姻状况;模型3在模型2的基础上增加基线年龄和基线状态。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

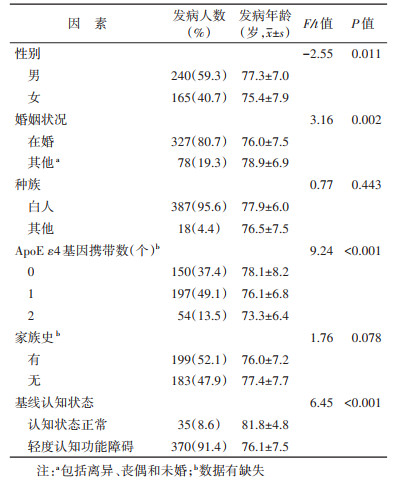

结果1. 一般情况: 随访期间进展成AD的研究对象共405名,其中男性240名,基线认知状态为MCI者370名,基线年龄为(74.0±6.9)岁。AD发病年龄为(76.6±7.5)岁,且男性AD发病年龄较女性晚1.9岁,在婚者比其他婚姻状况者早2.9岁。近一半(49.1%)参与者携带了1个ApoE ε4基因,其AD发病年龄较未携带者早2.0岁,较携带2个ApoE ε4基因者晚2.8岁。基线MCI者的AD发病年龄较基线CN者早5.7岁。不同种族、有无家族史之间AD发病年龄差异无统计学意义(P > 0.05)。见表 1。

2. AD发病年龄影响因素分析: 多元线性回归结果显示ApoE ε4基因携带数与AD发病年龄呈一定线性趋势,携带ApoE ε4基因数每增加1个,AD发病年龄早0.344年;基线年龄每增加1岁,AD发病年龄晚1.008岁(P < 0.001);基线认知状态为MCI者,其AD发病年龄比CN早4.007岁(P < 0.001)。见表 2。

3. 敏感性分析: 结果显示ApoE ε4基因携带数、基线年龄和基线认知状态对Y1和Y2的影响差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。家族史对Y2的影响差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05),有家族史的研究对象AD发病年龄(Y2)更大。在除去35名基线认知状态CN者后,ApoE ε4基因携带数和基线年龄对发病年龄(Y0del)的影响差异有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。见表 3。

本研究中AD发病年龄为(76.6±7.5)岁,晚于巴西圣保罗市人群[(73.4±6.5)岁]和加勒比西班牙裔人群的AD发病年龄[(73.3±10.6)岁][10-11]。入组偏倚可能是导致本研究AD发病年龄高的主要原因,ADNI在招募研究对象时为使CN人群的基线年龄与MCI和AD人群大致匹配,尽量减少年龄 < 70岁的CN者,且由于无法获得入组时就已经是AD,即基线认知状态为AD者的具体发病年龄(其AD发病年龄早于基线年龄),本研究排除了基线认知状态为AD者。然而经计算,被排除人群的基线年龄为(74.8±8.0)岁,低于本研究得到的AD发病年龄。

ApoE ε4基因携带数越多,AD发病年龄越早。有研究也证实ApoE ε4基因携带数与AD发病年龄有着显著的剂量效应关系,携带数量较多的人群AD发病年龄更早[12-13]。本研究发现ApoE ε4基因携带数与AD发病年龄呈一定线性趋势,携带2个ApoE ε4基因比携带1个基因者发病年龄早2.8岁,比未携带ApoE ε4基因者早4.8岁,这与挪威的一项研究结果相近[14]。此外,ApoE ε4基因携带数也被证实与认知功能的下降速度有关,携带者认知功能下降速度比未携带者更快,AD发病年龄更早[15-16]。

本研究中受教育年限对AD发病年龄的影响无统计学意义,这与教育可增加认知储备延缓AD发生的观点不一致[17-19]。认知储备学说认为大脑在发生AD神经病理学改变后,会使用现有的“认知储备/储存库”补偿病理学改变引起的功能下降[20-21]。学校教育、社会经济地位、社会参与和认知活动等被认为能增加认知储备,可延缓AD症状发生[19, 22]。但也有研究发现受教育年限与各认知领域随时间变化无关,与AD发病年龄也无关[10, 23]。还有研究得出相反的结果,即高文化程度的老年人认知功能下降速度更快,发生AD的年龄更早[24-25]。Roe等[25]认为受过更多教育的人更有可能从事认知相关工作,认知功能(如记忆、语言等领域)的细微变化可能会被更早发现,使这些人就医年龄更早,在发生AD后能更早被诊断出来,AD发病年龄更小。

本研究中基线状态为MCI的AD发病年龄较基线CN者早4.007岁,可能原因:一是MCI发展至AD历程较短。AD的自然病程包括较长的临床前阶段(CN阶段)、早期临床阶段(MCI阶段)和AD阶段,MCI是介于CN和AD之间的中间状态或过渡状态,因此MCI进展为AD的历程短于CN[26]。在控制基线年龄后,基线状态为MCI的AD发病年龄小于基线CN者。二是基线状态为MCI的平均基线年龄小。ADNI在招募研究对象时排除了年龄 < 70岁的CN者,而MCI者基线年龄 < 55岁被排除。本研究选取随访期间发生AD者为研究对象,在最终纳入样本中,基线状态为CN者的基线年龄(75.5岁)高于MCI者(73.9岁)。鉴于此,本研究在敏感性分析中剔除了基线为CN者35名,探索AD发病年龄的影响因素,并得到类似结果。

去除35名基线认知状态为CN者后的敏感性分析显示,男性的AD发病年龄比女性晚0.506岁,在婚者比其他婚姻状况者早0.603岁,有家族史者比无家族者晚0.550岁,差异均有统计学意义(P < 0.05)。也有研究表明女性认知功能下降速度快于男性,在婚者AD发病年龄更早[27-29]。其中性别差异可能与女性雌激素水平的下降有关。雌激素可刺激α分泌酶活性,从而增强淀粉样蛋白前体加工生成非β-淀粉样蛋白[30-31]。绝经后女性的雌激素,尤其是雌二醇显著减少,而男性的雌激素却没有明显变化[32],这导致女性的淀粉样斑块水平较男性更高,认知功能下降速度更快,进而更早发生AD。对于婚姻状况,de Oliveira等[29]认为在婚者发病年龄更早的可能原因是有伴侣存在使认知功能受损被更早发现,且有家族史者的AD发病年龄更晚这一结果与既往研究结论不一致[10, 33],与本研究中的单因素分析结果亦相反。这一矛盾结果可能由于本研究排除了基线认知状态为AD的人群,而排除的这部分人群中有家族史者的基线年龄[(73.8±7.5)岁]比无家族史者[(76.2±7.9)岁]更早,且均小于本研究得到的发病年龄[(76.6±7.5)岁],因此有关家族史与AD发病年龄之间的关系有待依赖更完备的数据进一步探讨。

本研究资料来源于纵向多中心研究,随访时间长,研究对象人群基数大,依从性较好,且进行了多种敏感性分析,结果更稳定可靠。本研究存在局限性。首先,由于研究随访过程中的时间间隔平均为6.6个月,无法确定AD发病年龄的确切时间;其次,由于研究对象存在入组偏倚,可能会使得到的AD发病年龄偏大;最后,影响因素多为人口学因素,未纳入生活行为方式、精神状况和慢性病等潜在因素。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 戎猛:数据整理、分析和解释、论文撰写;袁满琼:数据整理、统计学分析、技术和材料支持;方亚:酝酿和设计实验、内容审阅、论文指导、经费支持

| [1] |

World Health Organization. Dementia[EB/OL]. (2022-09-20)[2022-09-20]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

|

| [2] |

刘秀苹, 刘丽荣. 阿尔茨海默病的发病机制与相关危险因素[J]. 四川精神卫生, 2013, 26(4): 339-342. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3256.2013.04.027 Liu XP, Liu LR. Pathogenesis and associated risk factors for Alzheimer's disease[J]. Sichuan Ment Health, 2013, 26(4): 339-342. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-3256.2013.04.027 |

| [3] |

Ho GJ, Hansen LA, Alford MF, et al. Age at onset is associated with disease severity in Lewy body variant and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neuroreport, 2002, 13(14): 1825-1828. DOI:10.1097/00001756-200210070-00028 |

| [4] |

吴联, 汤锦磊, 张建敬. 阿尔茨海默病认知障碍进展速度的影响因素分析[J]. 心电与循环, 2022, 41(2): 162-164, 168. DOI:10.12124/j.issn.2095-3933.2022.2.2021-4577 Wu L, Tang JL, Zhang JJ. Influencing factors of the progression rate of cognitive impairment in Alzheimer's disease[J]. J Electrocardiol Circ, 2022, 41(2): 162-164, 168. DOI:10.12124/j.issn.2095-3933.2022.2.2021-4577 |

| [5] |

Ganguli M, Dodge HH, Shen CY, et al. Alzheimer disease and mortality: a 15-year epidemiological study[J]. Arch Neurol, 2005, 62(5): 779-784. DOI:10.1001/archneur.62.5.779 |

| [6] |

Go SM, Lee KS, Seo SW, et al. Survival of Alzheimer's disease patients in Korea[J]. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 2013, 35(3/4): 219-228. DOI:10.1159/000347133 |

| [7] |

Talar K, Vetrovsky T, van Haren M, et al. The effects of aerobic exercise and transcranial direct current stimulation on cognitive function in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis[J]. Age Res Rev, 2022, 81: 101738. DOI:10.1016/J.ARR.2022.101738 |

| [8] |

Gonzalez SC, Bamiou DE, Lewis G, et al. Feasibility of treating hearing loss to prevent dementia in MCI: Results of the face to face and remote interventions in the Treating Auditory impairment and Cognition Trial (TACT)[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2021, 17 Suppl 10: e055147. DOI:10.1002/ALZ.055148 |

| [9] |

Lee JH, Kim DY, Kim MG, et al. Preventing cognitive decline in older adults with mild cognitive impairment using integrated Korean and Western treatments: Initial results[J]. Alzheimers Dement, 2021, 17 Suppl 8: e052545. DOI:10.1002/ALZ.052545 |

| [10] |

de Oliveira FF, Bertolucci PHF, Chen ES, et al. Risk factors for age at onset of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease in a sample of patients with low mean schooling from São Paulo, Brazil[J]. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 2014, 29(10): 1033-1039. DOI:10.1002/gps.4094 |

| [11] |

Lee JH, Barral S, Cheng R, et al. Age-at-onset linkage analysis in Caribbean Hispanics with familial late-onset Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurogenetics, 2008, 9(1): 51-60. DOI:10.1007/S10048-007-0103-3 |

| [12] |

Calderón-Garcidueñas L, de La Monte SM. Apolipoprotein E4, gender, body mass index, inflammation, insulin resistance, and air pollution interactions: recipe for Alzheimer's disease development in Mexico City Young females[J]. J Alzheimers Dis, 2017, 58(3): 613-630. DOI:10.3233/JAD-161299 |

| [13] |

Carrasquillo MM, Crook JE, Pedraza O, et al. Late-onset Alzheimer's risk variants in memory decline, incident mild cognitive impairment, and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurobiol Aging, 2015, 36(1): 60-67. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.07.042 |

| [14] |

Sando SB, Melquist S, Cannon A, et al. APOE ε4 lowers age at onset and is a high risk factor for Alzheimer's disease; A case control study from central Norway[J]. BMC Neurol, 2008, 8(1): 9. DOI:10.1186/1471-2377-8-9 |

| [15] |

Evans RM, Hui S, Perkins A, et al. Cholesterol and APOE genotype interact to influence Alzheimer disease progression[J]. Neurology, 2004, 62(10): 1869-1871. DOI:10.1212/01.wnl.0000125323.15458.3f |

| [16] |

Todd M, Schneper L, Vasunilashorn SM, et al. Apolipoprotein E, cognitive function, and cognitive decline among older Taiwanese adults[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(10): e0206118. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0206118 |

| [17] |

Staff RT, Murray AD, Deary IJ, et al. What provides cerebral reserve?[J]. Brain, 2004, 127(Pt 5): 1191-1199. DOI:10.1093/brain/awh144 |

| [18] |

Alley D, Suthers K, Crimmins E. Education and cognitive decline in older Americans: results from the AHEAD sample[J]. Res Ag, 2007, 29(1): 73-94. DOI:10.1177/0164027506294245 |

| [19] |

Rosselli M, Uribe IV, Ahne E, et al. Culture, ethnicity, and level of education in Alzheimer's disease[J]. Neurotherapeutics, 2022, 19(1): 26-54. DOI:10.1007/S13311-022-01193-Z |

| [20] |

Stern Y. Cognitive reserve in ageing and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Lancet Neurol, 2012, 11(11): 1006-1012. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6 |

| [21] |

Stern Y, Barulli D. Cognitive reserve[J]. Handb Clin Neurol, 2019, 167: 181-190. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00011-X |

| [22] |

Li XR, Song RX, Qi XY, et al. Influence of cognitive reserve on cognitive trajectories: role of brain pathologies[J]. Neurology, 2021, 97(17): e1695-1706. DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000012728 |

| [23] |

Zahodne LB, Glymour MM, Sparks C, et al. Education does not slow cognitive decline with aging: 12-year evidence from the Victoria longitudinal study[J]. J Int Neuropsychol Soc, 2011, 17(6): 1039-1046. DOI:10.1017/S1355617711001044 |

| [24] |

del Ser T, Hachinski V, Merskey H, et al. An autopsy-verified study of the effect of education on degenerative dementia[J]. Brain, 1999, 122(Pt 12): 2309-2319. DOI:10.1093/brain/122.12.2309 |

| [25] |

Roe CM, Xiong CJ, Grant E, et al. Education and reported onset of symptoms among individuals with Alzheimer disease[J]. Arch Neurol, 2008, 65(1): 108-111. DOI:10.1001/archneurol.2007.11 |

| [26] |

张雯艳, 陆媛. 老年轻度认知功能障碍患者相关病因及治疗的研究进展[J]. 国际老年医学杂志, 2021, 42(1): 57-61. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-7593.2021.01.016 Zhang WY, Lu Y. Advances in etiology and treatment of mild cognitive impairment in older people[J]. Int J Geriatr, 2021, 42(1): 57-61. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-7593.2021.01.016 |

| [27] |

lin KA, Choudhury KR, Rathakrishnan BG, et al. Marked gender differences in progression of mild cognitive impairment over 8 years[J]. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 2015, 1(2): 103-110. DOI:10.1016/j.trci.2015.07.001 |

| [28] |

Holland D, Desikan RS, Dale AM, et al. Higher rates of decline for women and Apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers[J]. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol, 2013, 34(12): 2287-2293. DOI:10.3174/AJNR.A3601 |

| [29] |

de Oliveira FF, Bertolucci PHF, Chen ES, et al. Assessment of risk factors for earlier onset of sporadic Alzheimer's disease dementia[J]. Neurol India, 2014, 62(6): 625-630. DOI:10.4103/0028-3886.149384 |

| [30] |

Yaffe K, Haan M, Byers A, et al. Estrogen use, APOE, and cognitive decline: evidence of gene-environment interaction[J]. Neurology, 2000, 54(10): 1949-1954. DOI:10.1212/wnl.54.10.1949 |

| [31] |

Xu HX, Gouras GK, Greenfield JP, et al. Estrogen reduces neuronal generation of Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides[J]. Nat Med, 1998, 4(4): 447-451. DOI:10.1038/nm0498-447 |

| [32] |

Farage A, Miranda. Gender differences in skin aging and the changing profile of the sex hormones with age[J]. J Steroids Hormonal Sci, 2012, 3(2): 1000109. DOI:10.4172/2157-7536.1000109 |

| [33] |

Scarabino D, Gambina G, Broggio E, et al. Influence of family history of dementia in the development and progression of late-onset Alzheimer's disease[J]. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsych Genet, 2016, 171(2): 250-256. DOI:10.1002/ajmg.b.32399 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44