文章信息

- 丁银圻, 杨淞淳, 吕筠, 李立明.

- Ding Yinqi, Yang Songchun, Lyu Jun, Li Liming

- 老年人群心血管疾病风险预测模型研究进展

- A review on cardiovascular disease risk prediction models in the elderly

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(6): 1013-1020

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(6): 1013-1020

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20221104-00940

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-11-04

2. 中南大学湘雅医院皮肤科, 长沙 410008;

3. 北京大学公众健康与重大疫情防控战略研究中心, 北京 100191

2. Department of Dermatology, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, China;

3. Peking University Center for Public Health and Epidemic Preparedness & Response, Beijing 100191, China

在我国乃至全球范围内,心血管疾病(CVD)都是造成老年人群死亡和疾病负担的主要原因[1-2]。CVD风险预测模型(CVD模型)是实现老年人群CVD风险评估和指导一级预防的重要工具之一。本文阐述了在老年人群中构建CVD模型的必要性,介绍了当前国内外主要的老年人群CVD模型,列举了老年人群模型与一般人群模型的异同点,并总结了今后继续优化模型的几点方向。

1. 专门构建老年人群CVD模型的必要性:

(1)老年人群一级预防的内在需求:人口老龄化是导致CVD负担增加的重要驱动因素。全球疾病负担研究(GBD)的中国数据显示,从1990年到2019年,在因CVD死亡的人群中,60~89岁人口占比从75.0%上升至80.5%[3]。CVD给老年患者及其照护者和卫生系统带来了巨大的负担[4]。2019年我国60~89岁人口中由CVD导致的伤残调整寿命年(DALY)达6 491.4万人年,占该年龄组总DALY数的35.1%[3];2020年我国农村和城市≥60岁人口CVD死亡率分别为19 630.2/10万和16 641.9/10万,居各死因首位[1]。

老年人群中与CVD风险关联最强的是年龄[5],随年龄增长,心血管系统在分子、细胞、器官及系统水平的结构和功能的改变不断累积,导致发生CVD的风险不断增加[6]。尽管衰老是不可避免的生理过程,大量证据表明老年人群依然可以通过改变其他危险因素来降低CVD的发生风险[7-9]。在老年人群中,虽然传统危险因素与CVD风险的关联强度降低,由于CVD的发病率和危险因素的流行率非常高,老年人群中的归因风险仍然较高,危险因素干预的潜在收益大于中年人群[10]。此外,老年人群相比其他年龄人群,CVD负担更重,预期寿命更短,发生药物不良事件的风险更高,在进行CVD的危险因素干预时,更需要权衡个体的获益和风险。因此,老年人群更需要能够指导CVD精准预防实践的风险评估工具。

CVD模型综合多个危险因素来评估个体未来发生CVD的风险,有助于准确地识别高危人群以及从危险因素干预中获益最大的人群[11],以便开展临床风险沟通,根据风险分层情况采取有针对性的干预措施。CVD模型是实现老年人群CVD一级预防临床实践的重要工具之一。

(2)一般人群模型预测能力的不足:目前国内外已构建了较多的一般人群CVD模型,许多已被纳入各国临床指南,在指导人群CVD风险分层和一级预防方面发挥了重要作用[12]。但是,这些模型的构建和验证人群主要是35~64岁的中年人群,老年人群的比例相对不足[13],多数模型在老年人群中的预测效果不够理想,往往会高估其CVD风险[14-17]。一个模型的预测效果主要取决于模型纳入的预测因子的全面性、模型算法对于预测因子与结局之间关联形式拟合及效应大小估计的合理性以及竞争风险、删失数据等问题的处理[18]。将一般人群模型直接应用于老年人群时存在两个问题:首先,这些模型所采用的预测因子对老年人群的效应不同于中年人群。有研究发现传统危险因素对CVD风险的预测效果随着年龄的增长而减弱[19];甚至发现BMI、血清TC和血压与老年人群的死亡风险呈负关联,这种现象被称为“反向流行病学”(或“危险因素悖论”,如肥胖悖论)[20]。其次,老年人群常常罹患其他严重疾病,非CVD死亡的竞争风险增加。而一般人群模型通常采用传统Cox比例风险回归模型构建,没有考虑非CVD死亡的竞争风险,导致高估老年人群的CVD死亡风险[21]。专门构建老年人群的CVD模型有助于准确预测老年人的CVD风险,正确识别高危人群,避免风险高估和过度诊疗[22]。

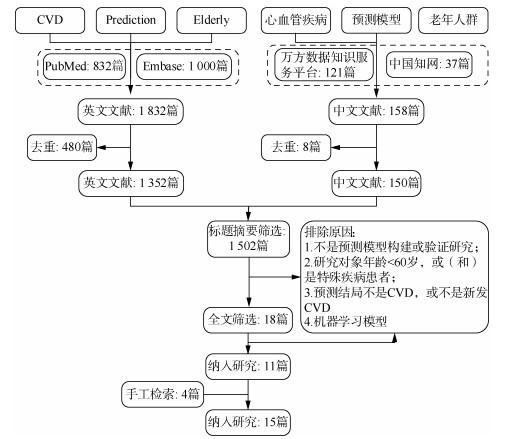

2. 国内外老年人群CVD预测模型现状:目前国内外构建的老年人群CVD预测模型在数量和质量上都有一定不足。在PubMed和Embase中使用“(cardiovascular disease OR stroke OR myocardial infarction OR ischemic heart disease OR coronary heart disease)AND(aged OR elder* OR old OR older OR oldest OR geriatric OR senior*)AND(predict* OR risk OR score OR model)”作为检索词,在中国知网和万方数据知识服务平台以“(心血管疾病OR缺血性心脏病OR冠状动脉疾病OR卒中OR心肌梗死)AND(老年人群)AND(预测模型OR风险评估OR风险预测)”作为检索词,进行检索(图 1)。检索时限为1998年至2022年7月15日,因为老年人群CVD预测模型研究大多在1998年之后开始出现[23]。以模型构建人群年龄≥60岁为标准,共检索到15篇针对老年人群构建CVD模型的文献,远少于一般人群模型。

|

| 图 1 文献检索流程图 |

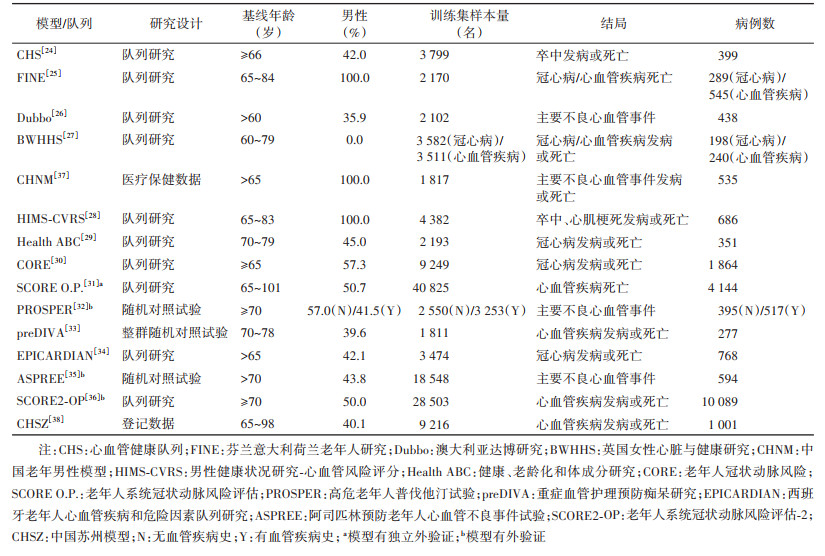

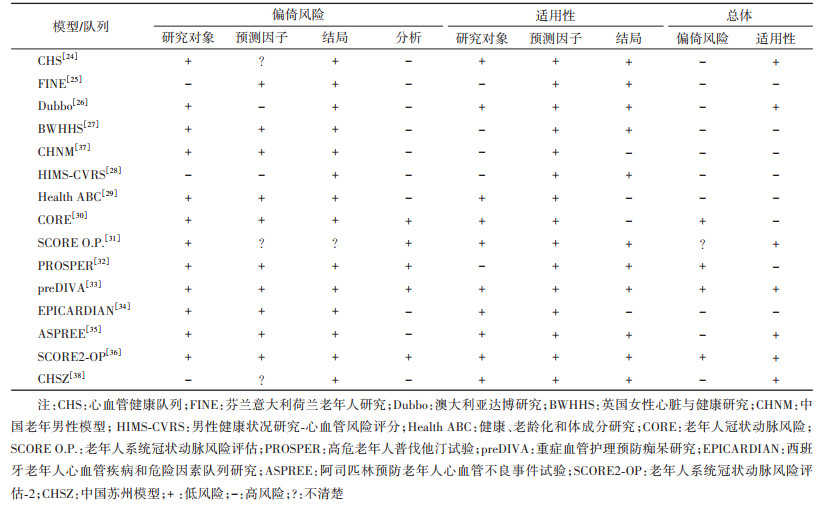

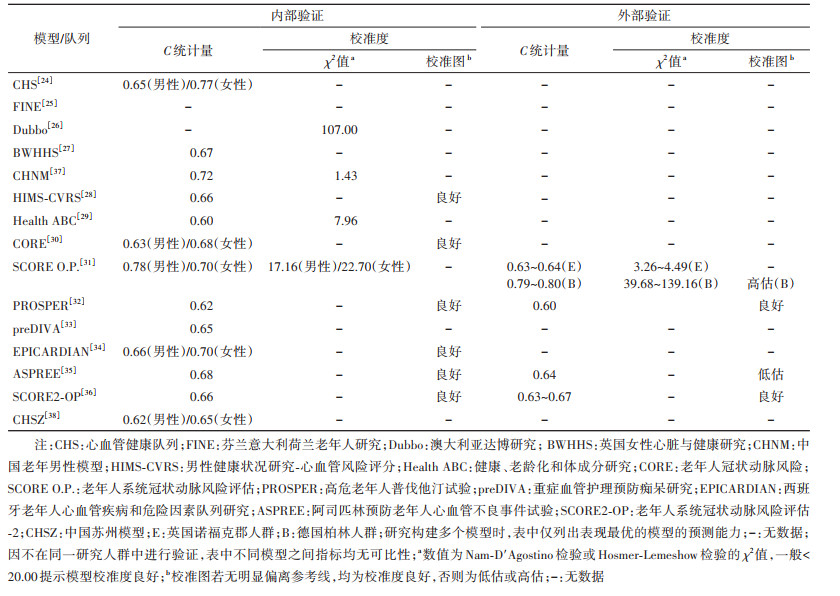

15个模型或其构建队列分别为心血管健康队列(CHS)[24]、芬兰意大利荷兰老年人研究(FINE)[25]、澳大利亚达博研究(Dubbo)[26]、英国女性心脏与健康研究(BWHHS)[27]、男性健康状况研究-心血管风险评分(HIMS-CVRS)[28]、健康、老龄化和体成分研究(Health ABC)[29]、老年人冠状动脉风险(CORE)[30]、老年人系统冠状动脉风险评估(SCORE O.P.)[31]、高危老年人普伐他汀试验(PROSPER)[32]、重症血管护理预防痴呆研究(preDIVA)[33]、西班牙老年人心血管疾病和危险因素队列研究(EPICARDIAN)[34]、阿司匹林预防老年人心血管不良事件试验(ASPREE)[35]、老年人系统冠状动脉风险评估-2(SCORE2-OP)[36],另有两篇中文文献,根据其特点分别称为中国老年男性模型(CHNM)[37]、中国苏州模型(CHSZ)[38]。多数研究人群来自美国、澳大利亚和欧洲地区。构建人群的基本情况、使用预测模型偏倚风险评估工具(prediction model risk of bias assessment tool,PROBAST)[39]评估的结果及模型的预测能力见表 1~3。多数模型构建人群的样本量相对较小,病例数超过1 000人的研究仅有4项[30-31, 36, 38]。建模人群绝大多数来自欧美国家,通常是基线未患CVD的老年人群。现有模型结局定义差异较大,既有单个结局事件,也有复合结局;既有仅关注死亡终点,也有同时纳入发病和死亡的所有结局事件(表 1)。10个模型报告时缺少方法、结果的重要信息。例如,缺少预测时间范围[27, 38],未描述具体的模型表达式或计算方法[24, 27-28, 32-34, 37-38],未完整报告内部验证结果[24-27, 38]等。根据PROBAST的评价结果,10个模型存在高偏倚风险,CORE、PROSPER、preDIVA和SCORE2-OP模型具有低偏倚风险,SCORE O.P.模型的偏倚风险不清楚(表 2)。偏倚风险的主要来源包括未考虑模型的过度拟合和拟合不足的问题,以及模型评价不恰当。13个模型在内部验证时仅表现出中等区分度(C统计量在0.60~0.75之间)[40];仅有4个模型经过外部验证(表 3)[31-32, 35-36]。

在我国老年人群中构建的CVD模型有2个。第一个由陈金宏等[37]于2010年基于某保健医院数据库的体检数据在1 817名男性群体中构建。尽管该模型在内部验证中显示出较好的区分度(C统计量为0.72)和校准度,由于样本量小,人群代表性不足,该模型并未得到推广与应用。另一个模型是2021年基于江苏省苏州市高新区2013-2019年卫生信息系统中9 216名老年人的体检数据、慢性病管理数据和死亡数据构建的多变量联合模型[38]。不同于传统模型仅基于基线数据,联合模型利用多次重复测量的纵向数据进行风险预测。该模型通过关联结构将一个纵向子模型和一个生存子模型联系起来,可以充分利用纵向数据中的轨迹信息和个体变异,能够更加高效、无偏地估计纵向过程和生存结局之间的关系,并能够随着纵向数据的更新实现风险的动态预测[41]。崔志贞等[38]还构建了Cox比例风险回归模型,以比较不同模型的预测能力。但是在内部验证中,两个模型的区分度均表现欠佳(男、女性Cox比例风险回归模型C统计量:0.62、0.60;联合模型C统计量:0.65、0.62),且未对校准度进行评价。

国外的老年人群CVD模型中应用较多的是欧洲地区的SCORE O.P.模型[31]和SCORE2-OP模型[36]。2016年,欧洲地区CVD临床预防指南推荐将系统冠状动脉风险评估(SCORE)模型用于40~65岁人群CVD一级预防[42]。为了补充用于≥65岁人群的风险评估工具,Cooney等[31]在意大利、丹麦、比利时和挪威共40 825人的老年队列中构建了SCORE O.P.模型,该研究具有较大的样本量,且在采用10倍交叉验证时表现出较好的区分度(男、女性模型C统计量:0.78、0.70)和校准度。该模型在欧洲癌症前瞻性调查-诺福克(EPIC-Norfolk)人群和德国柏林倡议研究(BIS)人群中进行了独立外验证[43-44]。SCORE O.P.模型在英国诺福克人群中的区分度较内部验证结果有明显下降,而校准度良好;在德国柏林人群中的区分度甚至好于内部验证结果,但高估人群观测风险约1.5~2.1倍。不过,德国柏林人群中位随访时长不到5年,结局事件仅有118例。该模型也被应用于南美国家人群的CVD风险预测[45-46]。

SCORE模型和SCORE O.P.模型预测的结局为CVD死亡,这一点备受争议。新开发的SCORE2模型[47]和SCORE2-OP模型[36]加入了CVD发病的软终点;不同于SCORE O.P.模型,SCORE2-OP模型采用了竞争风险模型算法,且在6个欧洲地区的队列共33万余人中进行了外部验证。不过,SCORE2-OP模型在内部和外部验证中的区分度均不理想(C统计量在0.63~0.67之间)。在2021年欧洲地区CVD预防临床实践指南中,SCORE2和SCORE2-OP模型分别被推荐用于40~69岁和≥70岁人群的CVD风险评估[48]。

3. 老年人群模型与一般人群模型的对比:适用于一般人群的CVD模型的发展较为成熟,多在大样本、多种族人群中构建和验证,多数已被纳入临床指南。而老年人群的CVD模型则仍处于缓慢发展阶段,得到的关注仍然不足。老年人群模型作为一般人群模型中特殊的一类,与一般人群模型在研究设计、预测因子、预测结局定义和预测时间范围、数据清理、验证方法和指标方面并无很大差异。但是,老年人群CVD模型在模型算法方面与一般人群模型存在差异。区别之处在于老年人群中存在来自其他疾病的竞争风险,部分老年人群CVD模型采用了竞争风险模型算法[30, 32-33, 36]。有多个研究提示,这种应用能够避免传统Cox比例风险回归模型对老年人群风险的高估,更接近真实世界的情况[21, 49]。

尽管常见的一般人群和老年人群CVD模型通常采用10年的预测时间范围,但这一时间范围是否仍适用于老年人群存在疑问。一项焦点小组访谈研究发现,大多数医疗保健消费者倾向于关注更接近当下的风险水平,10年风险因为太过遥远可能成为消费者推迟改变生活方式的借口[50]。特别对于老年人群来说,他们的预期寿命有限,危险因素干预的临床益处尚不完全明确,人群接受干预的意愿也不尽相同,10年风险的意义更加微小。因此,研究者认为5年的时间可能更适合老年人群[35]。也有观点认为,这种5年、10年的短期模型在很大程度上依赖于年龄,导致老年人总是比有相同危险因素的年轻人具有更高的CVD风险,可能造成老年人群的过度诊疗[51]。相比之下,使用终生风险模型可能更为恰当,可以结合既往研究发现的干预效果计算个体危险因素干预的终生益处,更有利于临床风险沟通,如LIFE-CVD模型[51-52]。

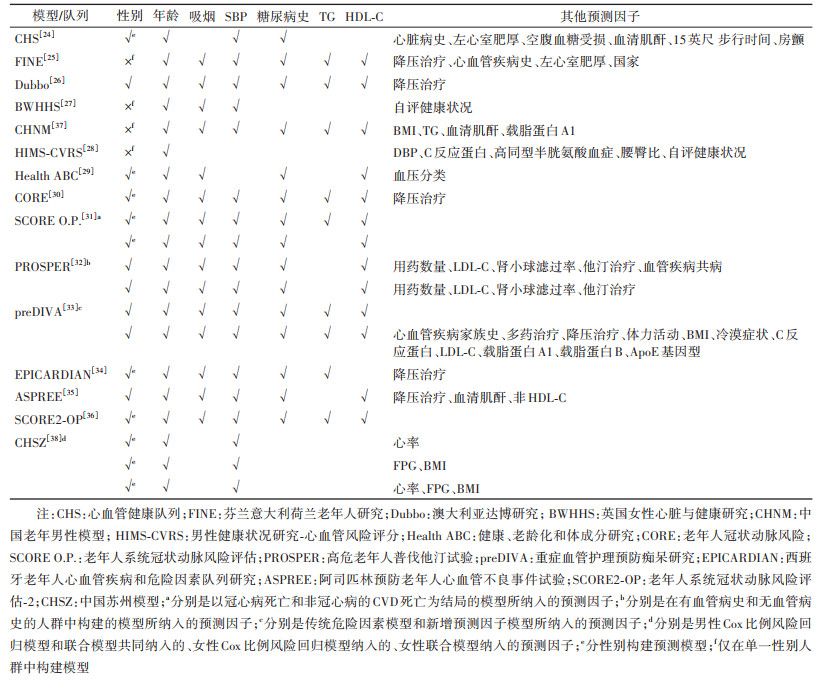

预测模型中纳入的预测因子通常是经较多研究确证的结局事件的危险因素。中年人群中发现的CVD危险因素大部分在老年人群中仍有效应,因此多数老年人群CVD模型所纳入的预测因子与一般人群模型并无很大差异,仍以传统危险因素为主(表 4)。最常见的预测因子是年龄、吸烟、SBP、糖尿病史、TC和HDL-C。其余预测因子可大致分为体格测量指标、生化指标、疾病及用药史3类。尽管纳入的预测因子种类相近,老年人群CVD模型在预测因子与结局的关联强度方面与一般人群模型存在差异。一篇系统综述显示,大多数研究中传统危险因素对老年人群的预测能力弱于中年人群[23]。年龄、性别和糖尿病史似乎是老年CVD最有价值的预测因素,其次是SBP、HDL-C和吸烟,而BMI、其他血压和胆固醇相关变量的预测价值似乎非常有限[23]。但是,该文纳入的研究在研究时期、纳入预测因子的数量和种类、结局事件、随访时长和偏倚风险方面存在显著异质性,限制了结果的可比性。

相比于一般人群模型,老年人群模型的预测能力有所下降。就模型预测表现而言,多数老年人群模型的校准度良好,改善了使用一般人群模型估计老年人群风险时的高估问题(表 3)。但老年人群模型的区分度不够理想,已知一般人群模型的C统计量在0.66~0.79之间[53],而老年人群模型的C统计量通常在0.60~0.70之间。出现这一现象可能的原因:①预测因子选取不够全面,未能捕捉到老年人群特有的、重要的预测因子;②目前采取的预测模型算法仍需进一步优化;③C统计量大小还受到模型验证人群危险因素和疾病风险分布的影响:病例与非病例间危险因素分布的重叠程度越高,模型的区分度越低;人群疾病风险分布变异度越小,模型可达到的最大C统计量越小[54]。因此,有研究者认为,使用校准度来评价老年人群模型可能更有意义[36]。良好的校准度表明模型预测的风险与验证人群的实际风险一致性较好,模型可以可靠地应用于该人群的临床实践[55]。

4. 老年人群CVD预测模型研究展望:目前适用于老年人群的CVD模型仍十分有限,且相关研究多局限于欧美国家。未来还需要更多大样本的高质量研究,在不同国家、种族、年龄范围[老年(60~74岁)与老老年(≥75岁)]的老年人群中开展构建、验证和应用CVD模型的研究,确定预测模型在不同特征人群中的表现、及其对老年群体预防CVD的实际价值,并规范研究方法和报告质量。

传统预测因子对于老年人群CVD风险的预测能力弱于中年人群,近年来提出的一些新型危险因素或许能够在传统危险因素的基础上改善模型的预测效果。一般人群模型中研究较多的新型危险因素可以分为亚临床动脉粥样硬化指标、血生化标志物和遗传工具3类,在老年人中研究较多的是前两类。其中,冠状动脉钙评分和生物标志物中的B型利钠肽原、C反应蛋白、肌钙蛋白受到较多关注[56-57]。遗传工具是指多基因风险评分(polygenic risk score,PRS),有两项研究分别讨论了冠心病(coronary heart disease,CHD)和缺血性卒中(ischemic stroke,IS)的PRS对于老年人群传统模型的增量价值[58-59]。结果显示,CHD的PRS在老年人群中表现良好,改善了传统模型对CHD的预测能力;而添加IS的PRS仅略微改善对IS的预测。考虑到老年人的特点,部分学者也提出了老年人特有的预测因子,包括与共病或衰弱相关的预测因子,如共病状态、服用药物数量、肾功能、衰弱指标[32, 35, 60-61],以及反映老年人群心理健康的冷漠状态、抑郁症状等指标[62]。这些新型预测因子对老年人群预测模型的改善作用还需要更多的研究证据支持,同时也需要综合考虑预测因子的获取成本、安全性和便利性。

有研究者认为,与传统的Cox比例风险回归模型算法相比,采用竞争风险模型算法可能有助于提高老年人群CVD风险评估的准确性[21, 49];与常见的10年风险预测模型相比,预测5年短期风险、终生风险可能更适合老年人群的风险沟通和模型应用[35, 51-52]。近年来,逻辑回归、支持向量机、随机森林、梯度提升机等机器学习方法被广泛应用于疾病预测模型研究中,该类方法可以通过高维数据中的大量变量来学习复杂的关系结构,通常不对变量类型、数据分布作严格的要求。陈金宏等[63]在Cox比例风险回归模型的同一数据集中采用BP神经网络构建了另一老年人群ICVD模型,发现其C统计量高于Cox比例风险回归模型(0.892 vs. 0.723)。然而,泛化能力不佳、外部验证缺乏和临床解读困难是机器学习模型领域面临的重大挑战。此外,随着个性化医疗的发展,能够通过不断更新的预测因子实现动态预测个体风险的模型可能更受欢迎,联合模型是目前实现这一目的的比较流行的方法。老年人群相对于其他年龄人群,身体机能及各项素质指标下降更快,动态模型相较于传统的定期风险模型更具时效性。并且,我国基本公共卫生服务每年会为≥65岁老年人免费提供包括体检在内的健康管理服务,定期更新的体检数据可以作为动态风险评估的直接数据来源,使得在老年人群中构建和应用动态模型更加便利可行[64]。不过,采用以上这些方法的模型仍在少数,不同方法间的对比和模型实际应用价值的研究也亟待开展。

5. 小结:在老年人群中开展CVD风险评估具有重要的公共卫生学意义。构建模型时需要考虑老年人群的预期寿命、共病和衰弱状态、传统危险因素预测能力的降低以及复杂的外推性,探索更多新的预测因子和采用新的模型构建方法有望进一步改进现有模型。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

| [1] |

国家卫生健康委员会. 中国卫生健康统计年鉴-2021[M]. 北京: 中国协和医科大学出版社, 2021. National Health Commission. China health statistics yearbook 2021[M]. Beijing: Peking Union Medical College Press, 2021. |

| [2] |

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular diseases[EB/OL]. (2021-06-11)[2022-09-01]. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

|

| [3] |

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME). GBD results tool[EB/OL]. (2019)[2022-09-22]. http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool.

|

| [4] |

Timmis A, Townsend N, Gale C, et al. European Society of Cardiology: Cardiovascular disease statistics 2017[J]. Eur Heart J, 2018, 39(7): 508-579. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehx628 |

| [5] |

North BJ, Sinclair DA. The intersection between aging and cardiovascular disease[J]. Circ Res, 2012, 110(8): 1097-1108. DOI:10.1161/circresaha.111.246876 |

| [6] |

Paneni F, Cañestro CD, Libby P, et al. The aging cardiovascular system: Understanding it at the cellular and clinical levels[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2017, 69(15): 1952-1967. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.064 |

| [7] |

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE, et al. Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older[J]. N Engl J Med, 2008, 358(18): 1887-1898. DOI:10.1056/nejmoa0801369 |

| [8] |

Afilalo J, Duque G, Steele R, et al. Statins for secondary prevention in elderly patients: A hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2008, 51(1): 37-45. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.063 |

| [9] |

Hermanson B, Omenn GS, Kronmal RA, et al. Beneficial six-year outcome of smoking cessation in older men and women with coronary artery disease[J]. N Engl J Med, 1988, 319(21): 1365-1369. DOI:10.1056/nejm198811243192101 |

| [10] |

Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB. The importance of cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly[J]. Am J Geriatr Cardiol, 1995, 4(2): 10-23. |

| [11] |

Dorresteijn JAN, Visseren FLJ, Ridker PM, et al. Estimating treatment effects for individual patients based on the results of randomised clinical trials[J]. BMJ, 2011, 343: d5888. DOI:10.1136/bmj.d5888 |

| [12] |

杨淞淳, 孙至佳, 吕筠, 等. 心血管疾病风险预测模型研究进展[J]. 中华心血管病杂志, 2022, 50(12): 1243-1251. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20220324-00202 Yang SC, Sun ZJ, Lyu J, et al. Research progress on risk prediction models of cardiovascular disease[J]. Chin J Cardiol, 2022, 50(12): 1243-1251. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20220324-00202 |

| [13] |

Zhao D, Liu J, Xie WX, et al. Cardiovascular risk assessment: A global perspective[J]. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2015, 12(5): 301-311. DOI:10.1038/nrcardio.2015.28 |

| [14] |

Koller MT, Steyerberg EW, Wolbers M, et al. Validity of the framingham point scores in the elderly: results from the Rotterdam Study[J]. Am Heart J, 2007, 154(1): 87-93. DOI:10.1016/j.ahj.2007.03.022 |

| [15] |

Nanna MG, Peterson ED, Wojdyla D, et al. The accuracy of cardiovascular pooled cohort risk estimates in U. S. older adults[J]. J Gen Intern Med, 2020, 35(6): 1701-1708. DOI:10.1007/s11606-019-05361-4 |

| [16] |

de Ruijter W, Westendorp RGJ, Assendelft WJJ, et al. Use of Framingham risk score and new biomarkers to predict cardiovascular mortality in older people: Population based observational cohort study[J]. BMJ, 2009, 338: a3083. DOI:10.1136/bmj.a3083 |

| [17] |

Yang SC, Han YT, Yu CQ, et al. Development of a model to predict 10-year risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and ischemic heart disease using the China Kadoorie Biobank[J]. Neurology, 2022, 98(23): e2307-2317. DOI:10.1212/wnl.0000000000200139 |

| [18] |

Moons KGM, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): Explanation and elaboration[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2015, 162(1): W1-73. DOI:10.7326/m14-0698 |

| [19] |

Hamer M, Chida Y, Stamatakis E. Utility of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular risk stratification across three age groups in subjects without existing cardiovascular diseases[J]. Am J Cardiol, 2009, 104(4): 538-542. DOI:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.04.020 |

| [20] |

Ahmadi SF, Streja E, Zahmatkesh G, et al. Reverse epidemiology of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in the geriatric population[J]. J Am Med Dir Assoc, 2015, 16(11): 933-939. DOI:10.1016/j.jamda.2015.07.014 |

| [21] |

Wolbers M, Koller MT, Witteman JCM, et al. Prognostic models with competing risks: Methods and application to coronary risk prediction[J]. Epidemiology, 2009, 20(4): 555-561. DOI:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a39056 |

| [22] |

Field TS, Gurwitz JH, Harrold LR, et al. Risk factors for adverse drug events among older adults in the ambulatory setting[J]. J Am Geriatr Soc, 2004, 52(8): 1349-1354. DOI:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52367.x |

| [23] |

van Bussel EF, Hoevenaar-Blom MP, Poortvliet RKE, et al. Predictive value of traditional risk factors for cardiovascular disease in older people: a systematic review[J]. Prev Med, 2020, 132: 105986. DOI:10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.105986 |

| [24] |

Lumley T, Kronmal RA, Cushman M, et al. A stroke prediction score in the elderly: Validation and web-based application[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2002, 55(2): 129-136. DOI:10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00434-6 |

| [25] |

Houterman S, Boshuizen HC, Verschuren WMM, et al. Predicting cardiovascular risk in the elderly in different European countries[J]. Eur Heart J, 2002, 23(4): 294-300. DOI:10.1053/euhj.2001.2898 |

| [26] |

Simons LA, Simons J, Palaniappan L, et al. Risk functions for prediction of cardiovascular disease in elderly Australians: The Dubbo Study[J]. Med J Aust, 2003, 178(3): 113-116. DOI:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05100.x |

| [27] |

May M, Lawlor DA, Brindle P, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk assessment in older women: can we improve on Framingham? British Women's Heart and Health prospective cohort study[J]. Heart, 2006, 92(10): 1396-1401. DOI:10.1136/hrt.2005.085381 |

| [28] |

Beer C, Alfonso H, Flicker L, et al. Traditional risk factors for incident cardiovascular events have limited importance in later life compared with the Health in Men Study Cardiovascular Risk Score[J]. Stroke, 2011, 42(4): 952-959. DOI:10.1161/strokeaha.110.603480 |

| [29] |

Rodondi N, Locatelli I, Aujesky D, et al. Framingham risk score and alternatives for prediction of coronary heart disease in older adults[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3): e34287. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0034287 |

| [30] |

Koller MT, Leening MJG, Wolbers M, et al. Development and validation of a coronary risk prediction model for older U. S. and European persons in the cardiovascular health study and the Rotterdam study[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2012, 157(6): 389-397. DOI:10.7326/0003-4819-157-6-201209180-00002 |

| [31] |

Cooney MT, Selmer R, Lindman A, et al. Cardiovascular risk estimation in older persons: SCORE O. P.[J]. Eur J Prev Cardiol, 2016, 23(10): 1093-1103. DOI:10.1177/2047487315588390 |

| [32] |

Stam-Slob MC, Visseren FLJ, Jukema JW, et al. Personalized absolute benefit of statin treatment for primary or secondary prevention of vascular disease in individual elderly patients[J]. Clin Res Cardiol, 2017, 106(1): 58-68. DOI:10.1007/s00392-016-1023-8 |

| [33] |

van Bussel EF, Richard E, Busschers WB, et al. A cardiovascular risk prediction model for older people: Development and validation in a primary care population[J]. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich), 2019, 21(8): 1145-1152. DOI:10.1111/jch.13617 |

| [34] |

Gabriel R, Muñiz J, Vega S, et al. Cardiovascular risk in the elderly population of Spain. The EPICARDIAN risk score[J]. Rev Clín Esp (Barc), 2022, 222(1): 13-21. DOI:10.1016/j.rceng.2021.05.003 |

| [35] |

Neumann JT, Thao LTP, Callander E, et al. Cardiovascular risk prediction in healthy older people[J]. GeroScience, 2022, 44(1): 403-413. DOI:10.1007/s11357-021-00486-z |

| [36] |

SCORE2-OP Working Group and ESC Cardiovascular Risk Collaboration. SCORE2-OP risk prediction algorithms: Estimating incident cardiovascular event risk in older persons in four geographical risk regions[J]. Eur Heart J, 2021, 42(25): 2455-2467. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab312 |

| [37] |

陈金宏, 吴海云, 何昆仑, 等. 老年男性人群缺血性心脑血管病预测模型的建立[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2010, 31(10): 1166-1169. Chen JH, Wu HY, He KL, et al. Establishment of the prediction model for ischemic cardiovascular disease of elderly male population under current health care program[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2010, 31(10): 1166-1169. |

| [38] |

崔志贞. 基于公共卫生数据的心血管疾病动态风险预测模型研究[D]. 苏州: 苏州大学, 2021. Cui ZZ. Research on predictive models for dynamic risk of cardiovascular disease based on public health data[D]. Suzhou: Soochow University, 2021. |

| [39] |

Moons KGM, Wolff RF, Riley RD, et al. PROBAST: a tool to assess risk of bias and applicability of prediction model studies: Explanation and elaboration[J]. Ann Intern Med, 2019, 170(1): W1-33. DOI:10.7326/m18-1377 |

| [40] |

Alba AC, Agoritsas T, Walsh M, et al. Discrimination and calibration of clinical prediction models: Users' guides to the medical literature[J]. JAMA, 2017, 318(14): 1377-1384. DOI:10.1001/jama.2017.12126 |

| [41] |

翟映红, 陈琪, 韩贺东, 等. 联合模型介绍及在医学研究中的应用[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2019, 40(11): 1456-1460. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.11.021 Zhai YH, Chen Q, Han HD, et al. Introduction of joint model and its applications in medical research[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2019, 40(11): 1456-1460. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2019.11.021 |

| [42] |

Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The sixth joint task force of the European society of cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2016, 37(29): 2315-2381. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 |

| [43] |

Piccininni M, Rohmann JL, Huscher D, et al. Performance of risk prediction scores for cardiovascular mortality in older persons: External validation of the SCORE OP and appraisal[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(4): e0231097. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0231097 |

| [44] |

Verweij L, Peters RJG, Reimer WJMSO, et al. Validation of the Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation-Older Persons (SCORE-OP) in the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2019, 293: 226-230. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.07.020 |

| [45] |

Sisa I. Cardiovascular risk assessment in elderly adults using SCORE OP model in a Latin American population: the experience from Ecuador[J]. Med Clin (Barc), 2018, 150(3): 92-98. DOI:10.1016/j.medcli.2017.07.021 |

| [46] |

Sisa I. Gender differences in cardiovascular risk assessment in elderly adults in Ecuador: evidence from a national survey[J]. J Investig Med, 2019, 67(4): 736-742. DOI:10.1136/jim-2018-000789 |

| [47] |

Hageman S, Pennells L, Ojeda F, et al. SCORE2 risk prediction algorithms: new models to estimate 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease in Europe[J]. Eur Heart J, 2021, 42(25): 2439-2454. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab309 |

| [48] |

Visseren FLJ, Mach F, Smulders YM, et al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: Developed by the Task Force for cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice with representatives of the European Society of Cardiology and 12 medical societies With the special contribution of the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC)[J]. Eur Heart J, 2021, 42(34): 3227-3337. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab484 |

| [49] |

Cooper H, Wells S, Mehta S. Are competing-risk models superior to standard Cox models for predicting cardiovascular risk in older adults? Analysis of a whole-of-country primary prevention cohort aged ≥65 years[J]. Int J Epidemiol, 2022, 51(2): 604-614. DOI:10.1093/ije/dyab116 |

| [50] |

Hill S, Spink J, Cadilhac D, et al. Absolute risk representation in cardiovascular disease prevention: Comprehension and preferences of health care consumers and general practitioners involved in a focus group study[J]. BMC Public Health, 2010, 10(1): 108. DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-10-108 |

| [51] |

Board JBS3. Joint British Societies' consensus recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (JBS3)[J]. Heart, 2014, 100(Suppl 2): ii1-67. DOI:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305693 |

| [52] |

Jaspers NEM, Blaha MJ, Matsushita K, et al. Prediction of individualized lifetime benefit from cholesterol lowering, blood pressure lowering, antithrombotic therapy, and smoking cessation in apparently healthy people[J]. Eur Heart J, 2020, 41(11): 1190-1199. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz239 |

| [53] |

Damen JAAG, Hooft L, Schuit E, et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: Systematic review[J]. BMJ, 2016, 353: i2416. DOI:10.1136/bmj.i2416 |

| [54] |

Cook NR. Use and misuse of the receiver operating characteristic curve in risk prediction[J]. Circulation, 2007, 115(7): 928-935. DOI:10.1161/circulationaha.106.672402 |

| [55] |

Rossello X, Dorresteijn JAN, Janssen A, et al. Risk prediction tools in cardiovascular disease prevention: A report from the ESC prevention of CVD programme led by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology (EAPC) in collaboration with the Acute Cardiovascular Care Association (ACCA) and the Association of Cardiovascular Nursing and Allied Professions (ACNAP)[J]. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care, 2020, 9(5): 522-532. DOI:10.1177/2048872619858285 |

| [56] |

Yano Y, O'Donnell CJ, Kuller L, et al. Association of coronary artery calcium score vs age with cardiovascular risk in older adults: an analysis of pooled population-based studies[J]. JAMA Cardiol, 2017, 2(9): 986-994. DOI:10.1001/jamacardio.2017.2498 |

| [57] |

Saeed A, Nambi V, Sun WS, et al. Short-term global cardiovascular disease risk prediction in older adults[J]. J Am Coll Cardiol, 2018, 71(22): 2527-2536. DOI:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.050 |

| [58] |

Neumann JT, Riaz M, Bakshi A, et al. Predictive performance of a polygenic risk score for incident ischemic stroke in a healthy older population[J]. Stroke, 2021, 52(9): 2882-2891. DOI:10.1161/strokeaha.120.033670 |

| [59] |

Neumann JT, Riaz M, Bakshi A, et al. Prognostic value of a polygenic risk score for coronary heart disease in individuals aged 70 years and older[J]. Circ: Genomic Precis Med, 2022, 15(1): e003429. DOI:10.1161/circgen.121.003429 |

| [60] |

Boreskie KF, Kehler DS, Costa EC, et al. Standardization of the fried frailty phenotype improves cardiovascular disease risk discrimination[J]. Exp Gerontol, 2019, 119: 40-44. DOI:10.1016/j.exger.2019.01.021 |

| [61] |

Veronese N, Cereda E, Stubbs B, et al. Risk of cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in frail and pre-frail older adults: Results from a meta-analysis and exploratory meta-regression analysis[J]. Ageing Res Rev, 2017, 35: 63-73. DOI:10.1016/j.arr.2017.01.003 |

| [62] |

Eurelings LSM, van Dalen JW, Ter Riet G, et al. Apathy and depressive symptoms in older people and incident myocardial infarction, stroke, and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data[J]. Clin Epidemiol, 2018, 10: 363-379. DOI:10.2147/clep.S150915 |

| [63] |

陈金宏, 吴海云, 何耀, 等. 基于BP神经网络的老年男性保健人群缺血性心脑血管病预测模型研究[J]. 第三军医大学学报, 2011, 33(8): 797-799. DOI:10.16016/j.1000-5404.2011.08.002 Chen JH, Wu HY, He Y, et al. Construction and evaluation of predictive model for ischemic cardiovascular diseases of senior men based on BP neural network[J]. J Third Mil Med Univ, 2011, 33(8): 797-799. DOI:10.16016/j.1000-5404.2011.08.002 |

| [64] |

国家卫生计生委. 国家基本公共卫生服务规范(第三版)[M]. 北京: 中国原子能出版社, 2017. National Health and Family Planning Commission. National basic public health service standard (third edition)[M]. Beijing: China Atomic Energy Press, 2017. |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44