文章信息

- 郭亚慧, 贺子龙, 姬庆龙, 周海健, 孟凡亮, 胡晓丰, 魏销玥, 马俊才, 杨玉花, 赵薇, 龙丽瑾, 王新, 范佳铭, 遇晓杰, 张建中, 华德, 闫笑梅, 王海滨.

- Guo Yahui, He Zilong, Ji Qinglong, Zhou Haijian, Meng Fanliang, Hu Xiaofeng, Wei Xiaoyue, Ma Juncai, Yang Yuhua, Zhao Wei, Long Lijin, Wang Xin, Fan Jiaming, Yu Xiaojie, Zhang Jianzhong, Hua De, Yan Xiaomei, Wang Haibin

- 我国食品来源金黄色葡萄球菌种群结构分析

- Population structure of food-borne Staphylococcus aureus in China

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(6): 982-989

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(6): 982-989

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20221206-01043

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-12-06

2. 中国疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所/传染病预防控制国家重点实验室/感染性疾病诊治协同创新中心, 北京 102206;

3. 北京大数据精准医学高级创新中心/北京航空航天大学医学与工程跨学科创新研究所/北京航空航天大学, 北京 100191;

4. 中国检验检疫科学研究院, 北京 100020;

5. 解放军疾病预防控制中心, 北京 100032;

6. 中国科学院微生物学研究所微生物资源与大数据中心, 北京 100101;

7. 吉林省疾病预防控制中心微生物检验所, 长春 130051;

8. 西北农林科技大学食品科学与工程学院, 西安 712100;

9. 海南省疾病预防控制中心, 海口 570203;

10. 北京市朝阳区疾病预防控制中心, 北京 100020

2. State Key Laboratory of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Collaborative Innovation Center for Diagnosis and Treatment of Infectious Diseases, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 102206, China;

3. Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Big Data-based Precision Medicine, Interdisciplinary Innovation Institute of Medicine and Engineering, Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Beijing 100191, China;

4. Chinese Academy of Inspection and Quarantine, Beijing 100020, China;

5. State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100032, China;

6. Microbial Resource and Big Data Center, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China;

7. Institute of Microbiology, Jilin Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Changchun 130051, China;

8. College of Food Science and Engineering, Northwest Agriculture & Forestry University, Xi'an 712100, China;

9. Hainan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Haikou 570203, China;

10. Chaoyang District Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing 100020, China

金黄色葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus aureus,金葡菌)是一种严重危害人类健康的条件致病菌,广泛存在于自然界中,可引起各种类型的感染。金葡菌产生的肠毒素可以引起食物中毒,是全球性的公共卫生问题[1-3]。2011-2016年我国报告了314起金葡菌食物中毒,涉及5 196例病例,其中1例死亡[4]。我国食源性疾病暴发监测系统2020年报告了4 662起暴发,其中金葡菌排名第三,仅次于沙门菌和副溶血性弧菌[5],而实际的病例数可能远超过这个数目。食物中毒是人类食用了产肠毒素金葡菌污染的食物而引起的。在我国,凉拌食品、牛奶、水产制品、米面制品和肉制品等各类食品均有金葡菌污染的报道,检出率为1%~56%,其中肉制品、米面制品和凉拌类等食品中金葡菌的检出率较高[6-10]。金葡菌有多种分子分型方法,近年来随着全基因组测序(WGS)技术的发展,基于基因组水平的分型技术广泛应用,利用基因组序列可以同时完成葡萄球菌蛋白A编码基因(staphylococcal protein A gene,spa)分型,多位点序列分型(MLST)以及耐甲氧西林金葡菌(MRSA)的葡萄球菌染色体mec基因盒(SCCmec)分型。WGS的分辨率更高,在进化研究、暴发调查方面极有优势[11-13]。

既往研究提示,不同种类的食品中可分离到不同优势克隆群的金葡菌[6-9, 14-17],但在分离时间、食品基质或地域覆盖度具有一定的局限性,缺乏基因组水平的进化分析。为进一步了解我国食源性金葡菌的种群结构,本研究对2006-2020年我国16个省份的763株金葡菌以WGS方法进行分子分型与系统发育树构建,为食品污染菌株的溯源分析和食品安全风险评估提供参考依据。

材料与方法1. 实验材料:

(1)菌株来源:本研究选取了2006-2020年中国16个省份的食品分离金葡菌763株,其中MRSA菌株58株(表 1)。菌株分离自9种食品基质,包括肉及肉制品(50.20%,384/763)、米面制品(16.51%,126/763)、水产及水产制品(12.19%,92/763)、果蔬制品(7.86%,60/763)、乳及乳制品(5.12%,39/763)、焙烤制品(3.67%,28/763)、豆制品(2.36%,18/763)、冷冻饮品(1.57%,12/763)和蛋及蛋制品(0.52%,4/763)。国外进口食品分离到的金葡菌31株,被纳入基因组系统发育树的构建(表 2)。

(2)仪器、试剂与方法:血液和组织DNA提取试剂盒(DNeasy blood and tissue kit,德国Qiagen公司);恒温震荡金属浴(中国杭州博日科技股份有限公司);Qubit 4.0(美国Thermo公司);PCR仪(德国Sensoquest公司);凝胶成像仪(美国GE公司);电泳仪(美国伯乐公司);2×Trans Start Fast Pfu PCR Super Mix及DNA Ladder Marker(中国北京全式金生物技术有限公司);PCR引物合成及产物测序(中国北京奥科生物有限公司);WGS(中国北京诺禾致源科技股份有限公司)。

2. 研究方法:

(1)菌株分离鉴定:金葡菌用哥伦比亚血平板,37 ℃培养18 h。菌株鉴定包括乳胶凝集实验和特异基因nuc PCR检测,mecA基因PCR检测用于确认MRSA菌株[18]。

(2)WGS、组装及注释:使用Qubit 4.0软件对全基因组DNA进行初步定量。之后采用二代高通量测序技术进行WGS,测序平台为Illumina NovaSeq PE150,构建350 bp片段文库进行双端测序,单条序列长为150 bp。测序得到的原始数据首先去掉低质量序列,采用READFQ 10软件进行预处理。经过预处理之后的有效数据使用SOAP denovo 2.04、SPAdes 3.13和ABySS组装软件进行组装,并使用CISA软件进行整合,使用gapclose 1.12等软件对初步组装结果进行优化,过滤掉500 bp以下片段供后续基因组分析。使用Prokka 1.14.5软件进行基因组注释。

(3)分子分型:经过质控后的全基因组序列进行spa(https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/spaTyper/)和SCCmec(https://cge.food.dtu.dk/services/SCCmecinder/)分型分析,使用mlst 2.23.0软件和PubMLST网站(https://pubmlst.org/)进行MLST分型,使用goeBURST 1.2.1软件获得克隆群;使用BioNumerics7.5软件创建基于ST型的最小生成树(MST)。

(4)系统发育树构建:使用Roary 3.13.0软件提取核心基因组,基于1 996个核心基因使用Fasttree软件构建系统发育树,使用ITOL软件(https://itol.embl.de)进行可视化。

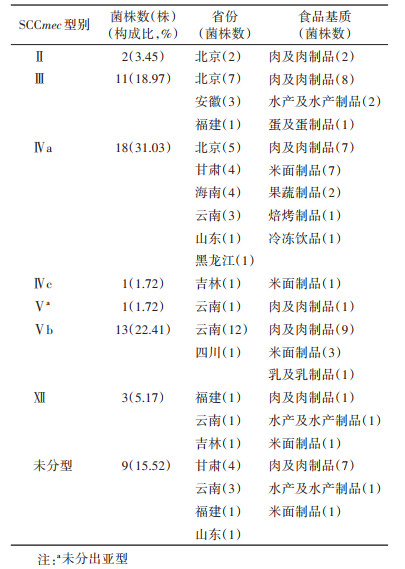

结果1. MRSA分布及SCCmec分型:763株金葡菌中共有58株(阳性率为7.60%)为MRSA分离株。MRSA菌株地域分布包括10个省份,以云南省(34.48%,20/58)和北京市(24.14%,14/58)菌株为主,占总MRSA的58.62%。MRSA菌株分离的食品基质以肉及肉制品为主(60.34%,35/58)。58株MRSA共分为7种SCCmec型别,其中9株菌为未知型别。主要型别分别是Ⅳa(31.03%,18/58)、Ⅴb(22.41%,13/58)和Ⅲ(18.97%,11/58),占总型别的72.41%(表 3)。Ⅳa型分布在6个省份和5种食品基质中;Ⅴb型分布在云南省和四川省,其中有8株菌来自2018年云南省的鲜禽肉;Ⅲ型分布在北京市、福建省和安徽省,其中7株菌均来自2009- 2010年北京市的熟肉制品。

2. spa分型:763株金葡菌分为160种型别,其中优势型别为t091(11.40%,87/763)、t189(7.21%,55/763)、t127(6.82%,52/763)、t002(6.55%,50/763)、t701(5.64%,43/763)、t437(4.98%,38/763)、t034(3.67%,28/763)、t796(3.15%,24/763)和t078(2.62%,20/763),这9种型别占所有菌株的52.03%。有17株菌型别未知。58株MRSA菌株有18种spa型别,主要以t437(36.21%,21/58)、t002(12.07%,7/58)和t030(12.07%,7/58)为主。

3. MLST及克隆群:763株金葡菌共分为90种ST型,其中20种为新ST型(ST7042~ST7058和ST7086~ST7088),72个ST型(80.0%,72/90)属于22个克隆群。主要克隆群为CC7、CC1、CC5、CC398、CC188、CC59、CC6、CC88、CC15和CC25,占82.44%(629/763)。根据菌株来源的食品基质种类进行分析,肉及肉制品来源菌株的优势克隆群为CC7、CC5、CC1、CC398、CC6、CC15、CC59和CC88,占该类菌株的76.56%(294/384)。米面制品来源菌株的优势克隆群为CC7、CC6、CC5、CC88、CC25和CC59,占该类菌株的65.87%(83/126)。水产及水产制品来源菌株的优势克隆群为CC6、CC1、CC15、CC25和CC188,占该类菌株的54.35%(50/92)。果蔬制品来源菌株的优势克隆群为CC1、CC7、CC188、CC20、CC5和CC59,占该类菌株的63.34%(42/60)。乳及乳制品来源菌株的优势克隆群为CC1、CC188、CC398和CC97,占该类菌株的76.92%(30/39),其中ST81是乳及乳制品的独有型别(图 1A)。优势克隆群中ST型和spa型别随着时间的变化呈多态性变化(图 1B)。CC7中ST7-t091逐年增多,而ST7-t796和ST943-t091减少。在CC1中ST81-t5100和ST1-t114有逐年增加的趋势。在CC5中ST5-t002始终为优势的ST型,ST965-t062和ST5-t179分别在2011年和2016年后出现。在CC188中整体ST-spa的流行逐渐多样化;ST188- t189处于下降趋势。在CC398中ST398-t011减少,逐渐被ST398-t034取代,ST398-t571是在2011年后出现且占比较大。CC59中ST59-t437和ST59- t163总体趋势在减少,而ST338-t437和ST338- t441在2016年之后出现。CC6的主要流行克隆群始终为ST6-t701。58株MRSA菌株共包括13种ST型,属于9种克隆群。结合ST、spa和SCCmec型别分析,以ST59-t437-Ⅳa(17.24%,10/58)、ST239- t030-Ⅲ(12.07%,7/58)、ST59-t437-Ⅴb(8.62%,5/58)、ST338-t437-Ⅴb(6.90%,4/58)和ST338-t441-Ⅴb(6.90%,4/58)为主。

|

| 注:A:763株食源性金葡菌的MLST数据构建的最小生成树,圆形的大小代表分离株的数量,圆形的区域分别用省份和食品基质着色,并用ST型标记,相同背景色的ST型为1个克隆群;B:不同ST-spa型别在不同年代中的构成比(%) 图 1 763株食源性金黄色葡萄球菌的多位点序列分型(MLST)数据构建的最小生成树和不同年代优势克隆群中ST-spa型别的构成比 |

4. 菌株基因组进化关系:基因组系统发育树可明显看出,所有菌株分为2个种群分支,命名为Clade1和Clade2,相同克隆群、ST和spa型别的菌株呈聚集分布(图 2)。Clade1全部为CC7甲氧西林敏感菌株,68.55%(85/124)的菌株为spa t091型。Clade1中有3个分支,包括2006年1月和8月广东省不同食品基质菌株、2008-2009年安徽省及2015年海南省肉及肉制品分离株。Clade2包括21种克隆群,涵盖了所有MRSA菌株。MRSA菌株按照SCCmec和ST型别呈聚集分布。CC1有4个分支,包括2017-2018年甘肃省的乳及乳制品菌株交叉聚集为进化关系较近的2个分支;2017年吉林省一起食物中毒事件的可疑食物聚集为1个分支;2015年海南省的肉及肉制品聚集为1个分支。在CC5中,2015年甘肃省、山东省菌株与2018年云南省的鸡肉来源菌株进化关系较近,spa型以t002为主;CC25中,2011年山东省和2012年福建省水产来源的菌株聚集为1个分支。CC88中,山东省2010、2011和2012年的多种食品基质来源菌株聚集为1个分支。在CC59和CC398中,分别均存在2017-2018和2017-2019年我国云南省禽肉来源菌株聚集。系统发育树显示,CC398、CC7、CC30、CC12和CC188中的国外分离株与我国分离株进化关系较远。CC5、CC15、CC20和CC45中进口食品分离株与国内分离株聚集为同一分支。其中CC398可分为3个主要分支,分别为丹麦进口菌株分支、多种食品基质来源菌株分支和肉类来源菌株分支。见图 2。

|

| 注:红色为菌株按照地区、时间和食品基质发生聚集 图 2 794株食源性金黄色葡萄球菌系统发育树 |

本研究对2006-2020年中国16个省份的763株食品来源金葡菌进行分子分型及基因组进化分析,结果提示,本研究菌株中的主要流行克隆群与既往研究结果基本相符,只是在排序上略有不同[10, 15, 17]。造成这种差别的原因可能由于菌株收集的省份、时间和食品基质构成略有不同。本研究的CC7菌株占比最多,这与2013-2015年云南省的食源性分离株中ST7为优势型别的报道相似[10]。本研究的CC7菌株广泛分布于2006-2019年13个省份各类食品基质中,以肉类中的畜肉(生猪肉)和禽肉(鸡肉)为主,占该类菌株的50%以上。既往研究显示,我国多地区健康猪、猪的生活环境(圈门、土壤和地面)、患有乳腺炎的牛以及人群中CC7均为优势克隆群,国外同样在健康牛中发现ST7-t091为优势克隆群[19-22]。由此推测污染的食品CC7菌株来源既包括动物,也包括人类。本研究通过基因组系统发育树发现,2006年广东省分离自不同月份和不同食品基质的CC7菌株聚集为一支,提示该克隆群的菌株可能在当地广泛流行。

目前国内报道的引起食物中毒暴发的金葡菌优势型别包括ST6-t701、ST943-t091、ST5-t002和ST59-t172[14, 23-28],这些菌株大部分为甲氧西林敏感菌株。本研究发现2006-2020年ST6-t701和ST5-t002始终为优势型别,提示ST6-t701和ST5-t002的菌株可能依然是我国引起食物中毒的主要流行型别。国内研究发现临床院内感染的MRSA菌株存在优势克隆群ST239-t030-MRSA被ST59-t437-MRSA替代的现象,产生这种变化的原因可能与后者具有更好的适应性和独特的毒力基因谱有关,优势型别的变化也会导致抗生素耐药谱发生改变[23, 29]。本研究发现类似现象,随着时间的推移,食品中菌株的优势克隆群内部的种群结构呈多态性变化,部分优势ST-spa型发生改变。本研究在优势克隆群种群内部发现变化的原因,以及这些变化对致病性、耐药的影响还需进一步研究。

CC59、CC398、CC7、CC188和CC5是我国医院及社区相关感染的优势型别[14, 30],同时CC398和CC7也是动物携带的主要克隆群[12, 25-26]。目前临床病例的CC7主要以甲氧西林敏感菌株为主,可以引起儿童(11~13岁)的皮肤和软组织感染,甚至引起菌血症[23, 31-32]。CC398、CC5和CC188是中国侵袭性血流感染的优势克隆群[29]。CC1是我国医院、水产品、原料乳及牛乳腺炎中的优势克隆群[33-35]。本研究选取菌株CC7、CC5、CC398、CC188克隆群全部为优势型别,提示这些分离株的污染与动物和人类活动密切相关,食品作为载体还可能会导致金葡菌的社区传播。系统发育树显示,CC398的17株丹麦进口冻猪肉分离株单独聚集,与我国肉类分离株进化关系较远;在CC7、CC30、CC12和CC188中也同样出现国外食品分离株与国内分离株进化关系较远的情况,提示这些菌株可能是在国外污染的。而在CC5、CC15、CC20和CC45中都存在国外分离株与国内分离株聚集为一支的情况,可能食物被进口到国内后受到污染。本研究2017-2018年分离自我国云南省禽肉的CC398菌株在系统发育树上关系较近,推测CC398菌株可能在当地禽类存在小范围流行。CC1中2017-2018年我国甘肃省原料乳分离株在系统发育树交叉聚集,提示该地区引起奶牛乳腺炎的流行克隆群在奶牛场可能存在广泛传播。

本研究中MRSA的检出率为7.60%,与既往报道的2011-2014年我国即食食品中的MRSA占比(8.70%)和我国24个省份203个城市的食物分离株中MRSA(7.90%)的占比相近[9, 36-37]。我国食品来源菌株的MRSA检出率为0.5%~29.5%[10, 37-38],这种差异可能是由于菌株选取的地域和食品基质的种类不同造成。在本研究中,大多数MRSA菌株来自肉及肉制品且属于CC59。CC59是我国社区相关MRSA的主要流行克隆群,通常携带SCCmec Ⅳ/Ⅴ,spa型别多为t437和t441[39-40]。目前,已有MRSA菌株引起食物中毒的报道,ST型包括ST15、ST59和ST338[17, 36, 41-42]。本研究发现3株主要分离自猪肉的ST9型MRSA携带Ⅻ型SCCmec。ST9是亚洲猪和养殖人员主要携带的MRSA型别[43]。Ⅻ是一种新型的SCCmec型别,ST9-MRSA-Ⅻ菌株在中国西北部和东南部患乳腺炎奶牛的牛奶样本和哈尔滨市猪的鼻拭子中均有报道[19, 44]。基因组进化研究发现,我国猪携带的ST9-MRSA-Ⅻ与牛和人相关的菌株聚集在一起,提示ST9-MRSA-Ⅻ在猪、牛和人之间传播,它的成功定植可能是由于获得了各种可移动遗传元件[45]。本研究在食品中发现的该型菌株,提示食品也是ST9-MRSA-Ⅻ的潜在传播途径。耐药菌通过食品作为载体在社区中的传播,将会成为食品安全防控的重要挑战。

本研究发现我国食品污染菌株存在优势克隆群,这与我国医院、社区感染和食物中毒的克隆群存在重叠现象,提示食品作为病原体社区传播和食物中毒的载体,需高度关注。优势克隆群内部的群体构成随着时间的变化,呈多态性变化,但2006-2020年ST6-t701和ST5-t002始终为食品污染菌株的优势型别,提示ST6-t701和ST5-t002的菌株依然是我国引起食物中毒的主要流行型别。基因组系统发育树分析为国际进口食品及国内食品污染菌株的溯源分析提供了参考数据。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 郭亚慧:数据整理与分析、实验操作、论文撰写;贺子龙、姬庆龙、周海健、赵薇、王新、遇晓杰:菌株收集、实验设计与完善;孟凡亮、胡晓丰、马俊才、张建中、华德:数据分析、论文指导;魏销玥、杨玉花、龙丽瑾、范佳铭:实验操作与完善、数据整理;闫笑梅、王海滨:研究设计、论文指导修改以及审阅、经费支持

| [1] |

Hennekinne JA, de Buyser ML, Dragacci S. Staphylococcus aureus and its food poisoning toxins: characterization and outbreak investigation[J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2012, 36(4): 815-836. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00311.x |

| [2] |

Tong SYC, Davis JS, Eichenberger E, et al. Staphylococcus aureus infections: epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and management[J]. Clin Microbiol Rev, 2015, 28(3): 603-661. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00134-14 |

| [3] |

Rhee Y, Aroutcheva A, Hota B, et al. Evolving epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia[J]. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol, 2015, 36(12): 1417-1422. DOI:10.1017/ice.2015.213 |

| [4] |

Liu JK, Bai L, Li WW, et al. Trends of foodborne diseases in China: lessons from laboratory-based surveillance since 2011[J]. Front Med, 2018, 12(1): 48-57. DOI:10.1007/s11684-017-0608-6 |

| [5] |

Li HQ, Li WW, Dai Y, et al. Characteristics of settings and etiologic agents of foodborne disease outbreaks - China, 2020[J]. China CDC Wkly, 2021, 3(42): 889-893. DOI:10.46234/ccdcw2021.219 |

| [6] |

吴任之, 张翼, 王鑫, 等. 雅安市部分市售凉菜中金黄色葡萄球菌污染调查及分子分型[J]. 中国食品卫生杂志, 2022, 34(6): 1257-1262. DOI:10.13590/j.cjfh.2022.06.020 Wu RZ, Zhang Y, Wang X, et al. Investigation and molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus in cold dishes sold in the market of Ya'an[J]. Chin J Food Hyg, 2022, 34(6): 1257-1262. DOI:10.13590/j.cjfh.2022.06.020 |

| [7] |

Dai JS, Wu S, Huang JH, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from pasteurized milk in China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 641. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00641 |

| [8] |

Wu S, Huang JH, Wu QP, et al. Prevalence and characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from retail vegetables in China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 1263. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01263 |

| [9] |

Yang XJ, Zhang JM, Yu SB, et al. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in retail ready-to-eat foods in China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2016, 7: 816. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2016.00816 |

| [10] |

Liao F, Gu WP, Yang ZS, et al. Molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from food surveillance in southwest China[J]. BMC Microbiol, 2018, 18(1): 91. DOI:10.1186/s12866-018-1239-z |

| [11] |

Ruppitsch W, Indra A, Stoger A, et al. Classifying spa types in complexes improves interpretation of typing results for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus[J]. J Clin Microbiol, 2006, 44(7): 2442-2448. DOI:10.1128/JCM.00113-06 |

| [12] |

Feil EJ, Cooper JE, Grundmann H, et al. How clonal is Staphylococcus aureus?[J]. J Bacteriol, 2003, 185(11): 3307-3316. DOI:10.1128/JB.185.11.3307-3316.2003 |

| [13] |

Goldberg B, Sichtig H, Geyer C, et al. Making the leap from research laboratory to clinic: challenges and opportunities for next-generation sequencing in infectious disease diagnostics[J]. mBio, 2015, 6(6): e01888-15. DOI:10.1128/mBio.01888-15 |

| [14] |

Lv GP, Jiang RP, Zhang H, et al. Molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus from food samples and food poisoning outbreaks in Shijiazhuang, China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2021, 12: 652276. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.652276 |

| [15] |

容冬丽, 吴清平, 吴诗, 等. 我国部分地区即食食品和蔬菜中金黄色葡萄球菌污染分布及耐药和基因分型情况[J]. 微生物学报, 2018, 58(2): 314-323. DOI:10.13343/j.cnki.wsxb.20170144 Rong DL, Wu QP, Wu S, et al. Prevalence, antimicrobial susceptibility, and genetic characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus from retail ready-to-eat foods and vegetables in some regions of China[J]. Acta Microbiol Sin, 2018, 58(2): 314-323. DOI:10.13343/j.cnki.wsxb.20170144 |

| [16] |

Rong DL, Wu QP, Xu MF, et al. Prevalence, virulence genes, antimicrobial susceptibility, and genetic diversity of Staphylococcus aureus from retail aquatic products in China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 714. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00714 |

| [17] |

Wang W, Baker M, Hu Y, et al. Whole-genome sequencing and machine learning analysis of Staphylococcus aureus from multiple heterogeneous sources in China reveals common genetic traits of antimicrobial resistance[J]. mSystems, 2021, 6(3): e0118520. DOI:10.1128/mSystems.01185-20 |

| [18] |

Merlino J, Watson J, Rose B, et al. Detection and expression of methicillin/oxacillin resistance in multidrug- resistant and non-multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Central Sydney, Australia[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2002, 49(5): 793-801. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkf021 |

| [19] |

Li TM, Lu HY, Wang X, et al. Molecular characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus causing bovine mastitis between 2014 and 2015[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2017, 7: 127. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2017.00127 |

| [20] |

Zhou YY, Li XH, Yan H. Genotypic characteristics and correlation of epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus in healthy pigs, diseased pigs, and environment[J]. Antibiotics (Basel), 2020, 9(12): 839. DOI:10.3390/antibiotics9120839 |

| [21] |

Conceição T, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. Healthy bovines as reservoirs of major pathogenic lineages of Staphylococcus aureus in Portugal[J]. Microb Drug Resist, 2017, 23(7): 845-851. DOI:10.1089/mdr.2017.0074 |

| [22] |

Ye XH, Liu WD, Fan YP, et al. Frequency-risk and duration-risk relations between occupational livestock contact and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage among workers in Guangdong, China[J]. Am J Infect Control, 2015, 43(7): 676-681. DOI:10.1016/j.ajic.2015.03.026 |

| [23] |

Li SG, Sun SJ, Yang CT, et al. The changing pattern of population structure of Staphylococcus aureus from bacteremia in China from 2013 to 2016: ST239-030-MRSA replaced by ST59-t437[J]. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 332. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00332 |

| [24] |

Li GH, Wu SZ, Luo W, et al. Staphylococcus aureus ST6-t701 isolates from food-poisoning outbreaks (2006-2013) in Xi'an, China[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2015, 12(3): 203-206. DOI:10.1089/fpd.2014.1850 |

| [25] |

Zhao XN, Hu M, Zhao C, et al. Whole-genome epidemiology and characterization of methicillin- susceptible Staphylococcus aureus ST398 from retail pork and bulk tank milk in Shandong, China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2021, 12: 764105. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.764105 |

| [26] |

Yan XM, Wang B, Tao XX, et al. Characterization of Staphylococcus aureus strains associated with food poisoning in Shenzhen, China[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2012, 78(18): 6637-6642. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01165-12 |

| [27] |

Chen Q, Xie SM. Genotypes, enterotoxin gene profiles, and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus associated with foodborne outbreaks in Hangzhou, China[J]. Toxins (Basel), 2019, 11(6): 307. DOI:10.3390/toxins11060307 |

| [28] |

王多, 陶晓霞, 王文周, 等. ST6型金黄色葡萄球菌食物中毒菌株的毒力因子分析[J]. 中国病原生物学杂志, 2021, 16(1): 64-70, 75. DOI:10.13350/j.cjpb.210113 Wang D, Tao XX, Wang WZ, et al. Virulence factors of sequence type (ST) 6 Staphylococcus aureus in food poisoning outbreaks[J]. J Pathogen Biol, 2021, 16(1): 64-70, 75. DOI:10.13350/j.cjpb.210113 |

| [29] |

Jin Y, Zhou WX, Zhan Q, et al. Genomic epidemiology and characterisation of penicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus isolates from invasive bloodstream infections in China: an increasing prevalence and higher diversity in genetic typing be revealed[J]. Emerg Microbes Infect, 2022, 11(1): 326-336. DOI:10.1080/22221751.2022.2027218 |

| [30] |

Dong Q, Liu YL, Li WH, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus infection in neonates[J]. Infect Drug Resist, 2020, 13: 4589-4600. DOI:10.2147/IDR.S284781 |

| [31] |

Wu S, Huang JH, Wu QP, et al. Staphylococcus aureus isolated from retail meat and meat products in China: incidence, antibiotic resistance and genetic diversity[J]. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 2767. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02767 |

| [32] |

Gu FF, Chen Y, Dong DP, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus among patients with skin and soft tissue infections in two Chinese hospitals[J]. Chin Med J, 2016, 129(19): 2319-2324. DOI:10.4103/0366-6999.190673 |

| [33] |

Song MH, Bai YL, Xu J, et al. Genetic diversity and virulence potential of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from raw and processed food commodities in Shanghai[J]. Int J Food Microbiol, 2015, 195: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.11.020 |

| [34] |

Meng D, Wu YH, Meng QL, et al. Antimicrobial resistance, virulence gene profile and molecular typing of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from dairy cows in Xinjiang Province, northwest China[J]. J Glob Antimicrob Resist, 2019, 16: 98-104. DOI:10.1016/j.jgar.2018.08.024 |

| [35] |

Geng W, Yang Y, Wang C, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections caused by community-associated methicillin- resistant staphylococcus aureus among children in China[J]. Acta Paediatr, 2010, 99(4): 575-580. DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2009.01645.x |

| [36] |

Wu S, Huang JH, Zhang F, et al. Prevalence and characterization of food-related methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 304. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00304 |

| [37] |

Wang W, Baloch Z, Jiang T, et al. Enterotoxigenicity and antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from retail food in China[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 2256. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02256 |

| [38] |

周勇, 吴新伟, 胡玉山, 等. 2009-2018年广州市即食食品中金黄色葡萄球菌污染情况和菌型特征[J]. 中国食品卫生杂志, 2021, 33(4): 444-450. DOI:10.13590/j.cjfh.2021.04.008 Zhou Y, Wu XW, Hu YS, et al. Contamination status and characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus in ready-to-eat foods in Guangzhou from 2009 to 2018[J]. Chin J Food Hyg, 2021, 33(4): 444-450. DOI:10.13590/j.cjfh.2021.04.008 |

| [39] |

Li J, Wang LJ, Ip M, et al. Molecular and clinical characteristics of clonal complex 59 methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in Mainland China[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(8): e70602. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0070602 |

| [40] |

Yang X, Qian SY, Yao KH, et al. Multiresistant ST59-SCCmec Ⅳ-t437 clone with strong biofilm-forming capacity was identified predominantly in MRSA isolated from Chinese children[J]. BMC Infect Dis, 2017, 17(1): 733. DOI:10.1186/s12879-017-2833-7 |

| [41] |

Zhang PF, Miao X, Zhou LH, et al. Characterization of Oxacillin-susceptible mecA-positive Staphylococcus aureus from food poisoning outbreaks and retail foods in China[J]. Foodborne Pathog Dis, 2020, 17(11): 728-734. DOI:10.1089/fpd.2019.2774 |

| [42] |

Zhang H, Qin LY, Jin CP, et al. Molecular characteristics and antibiotic resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from patient and food samples in Shijiazhuang, China[J]. Pathogens, 2022, 11(11): 1333. DOI:10.3390/pathogens11111333 |

| [43] |

Chuang YY, Huang YC. Livestock-associated meticillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Asia: an emerging issue?[J]. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2015, 45(4): 334-340. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.12.007 |

| [44] |

Wu ZW, Li F, Liu DL, et al. Novel type Ⅻ staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec harboring a new cassette chromosome recombinase, CcrC2[J]. Antimicrob Agents Chemother, 2015, 59(12): 7597-7601. DOI:10.1128/AAC.01692-15 |

| [45] |

Zhou WY, Li XH, Osmundson T, et al. WGS analysis of ST9-MRSA-Ⅻ isolates from live pigs in China provides insights into transmission among porcine, human and bovine hosts[J]. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2018, 73(10): 2652-2661. DOI:10.1093/jac/dky245 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44