文章信息

- 范宇峰, 李臻鹏, 遇晓杰, 李哲, 周海健, 张亚淋, 甘晓婷, 华德, 卢昕, 阚飙.

- Fan Yufeng, Li Zhenpeng, Yu Xiaojie, Li Zhe, Zhou Haijian, Zhang Yalin, Gan Xiaoting, Hua De, Lu Xin, Kan Biao

- 城市对海口市南渡江的微生物群落及其毒力因子与抗生素耐药基因组的影响

- Study of the urban-impact on microbial communities and their virulence factors and antibiotic resistance genomes in the Nandu River, Haikou

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2023, 44(6): 974-981

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2023, 44(6): 974-981

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn112338-20221229-01090

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2022-12-29

2. 海南省疾病预防控制中心检验检测所, 海口 570203;

3. 中国疾病预防控制中心传染病预防控制所/传染病预防控制国家重点实验室, 北京 102206

2. Inspection and Testing Institute, Hainan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Haikou 570203, China;

3. National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention/State Key Laboratory of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Beijing 102206, China

城市河流承载了城市中各类再生水以及污水,并且作为城市的重要水资源和环境载体,对人类的健康和生产生活具有重要影响。然而,随着城市扩张建设和人口增加,几乎所有城市内河流都面临着严重的环境污染,尤其是城市河流承受了较高水平的抗生素耐药基因(ARGs)污染[1-2]。水是细菌重要的栖息地和繁殖地,在环境与人类和其他动物之间传播抗生素耐药方面发挥着重要作用[3]。在过去的几十年中,抗生素滥用使水生环境遭受了严重的抗生素污染[4-5]。抗生素选择压力为环境中的细菌维持ARGs的携带提供了适宜的环境[6-7],从而促进了耐药菌的发生和增殖,以及耐药基因的传播[8-10]。当人类摄入被ARGs污染的水和食物,或直接暴露于含有抗生素耐药菌的环境中[11-12],可能会对健康造成潜在威胁。开展有针对性的环境监测,是研究和处理环境健康问题的关键,也有利于相关决策和政策的制定,对保障人群健康具有重要意义[13-14]。

南渡江是海南省最大的河流,江水穿过海口市,最终汇入琼州海峡。南渡江不但是海口市重要的城市饮用水源,同时其周边汇集了丰富的渔业、农业以及休闲旅游产业等[15]。城镇居民污水、养殖业等产生污水中的抗生素污染物排入河流后增加了人群暴露于ARGs的概率和危险。本研究在海口市南渡江海口段进行连续河水样本采集,并基于PacBio环形一致性16S rRNA全长测序技术和宏基因组测序技术,描述和分析了这一区域的细菌群落(BAC)结构、ARGs、毒力因子(VFs)和可移动遗传元件(MGEs)的多样性和丰度,并分析ARGs和VFs的传播模式。

材料与方法1. 研究区域和样本采集:根据采集样本与海口市的相对位置,将研究区域分为前段(HN01~HN03)、中段(HN04~HN06)和后段(HN07~HN09)。其中前段位于海口市上游,受城市化影响较小;中段位于海口市中心,受城市化和人为扰动程度高;后段位于南渡江河口区域,紧邻琼州海峡。每段研究区域包含3个连续采样点,2020年10月15日在每个采样点平行采集6份水体样本作为生物学重复样本,共3 L,充分混合后储存于无菌储水袋中。其中1 L水保存于4 ℃冰箱用于样本理化指标的测定,2 L水保存于-80 ℃冰箱用于DNA提取和进一步分析。共采集了9份河流表层(1 m)水体样本,采样区域全长16.2 km。

2. DNA提取与测序:将2 L水样通过0.22 μm膜过滤器(德国Millipore公司)过滤以收集细菌。使用DNeasy® PowerSoil Kit试剂盒(德国Qiagen公司)提取样本的总DNA。

采用环形一致性测序方法,对样本进行16S rRNA基因全长测序方法以检测细菌多样性和群落结构。使用SMRTbellTM Template Prep Kit试剂盒(美国PacBio公司)生成测序文库,在PacBio Sequel平台(美国PacBio公司)上进行测序。

采用宏基因组二代测序技术,获得样本中的核酸序列以分析ARGs、VFs和MGEs等信息。使用MGIEasy Fast PCR-FREE FS Library Prep Set试剂盒(中国华大智造公司)和DNBSEQ OneStep DNB Make Regent Kit 2.0试剂盒(中国华大智造公司)构建测序文库。使用DNBSEQ-2000RS测序平台(中国华大智造公司)进行测序。对测序获得的原始数据进行质控后获得有效数据并进一步进行分析。

3. 微生物群落分析:使用UPARSE 11.0软件对所有样本的有效数据进行聚类[16],97%同一性的序列被聚类为操作分类单元(OTUs)。使用Mothur软件[17]和SILVA ribosomal RNA gene数据库[18]对OTUs序列进行物种注释(阈值为0.8~1.0),以获得样本中微生物的各个分类级别信息。

4. ARGs、VFs和基因扩散模式分析:基于ResFinder 4.1数据库[19]、VFs数据库[20],分别对ARGs和VFs的多样性和丰度进行分析。使用SOAP 2软件进行测序数据与数据库比对,参数设置为-r 1,-m 100,-x 1 000,-M 4[21]。根据Greengenes数据库进行本地比对[22],并通过Bowtie 2[23]和SAMtools 1.9软件[24]确定每个样本中16S rRNA序列的丰度。以相同方法,通过mobilegeneticelement数据库分析基因水平转移相关的MGEs数据[25]。每个样本的ARGs、MGEs和VFs丰度注释结果进行标准化处理(ARGs、VFs、MGEs的绝对丰度除以16S rRNA的丰度)后用于后续数据分析。

5. 统计学分析与数据可视化:采用K-W检验进行数据显著差异性比较。通过QIIME 11.9.1软件计算每个样本中BAC的α多样性指数:香浓指数、辛普森指数、Chao1指数和ACE指数[26]。应用主坐标分析(PCoA)方法和基于Bray-Curtis多样性距离的非加权组平均法聚类分析不同样本之间的差异性。通过普氏分析和曼特尔检验分别对ARGs、VFs与BAC(门水平)及MGEs的相关性和一致性进行分析。统计学分析以及数据可视化均通过R 4.1.2软件完成。双侧检验,检验水准α=0.05。

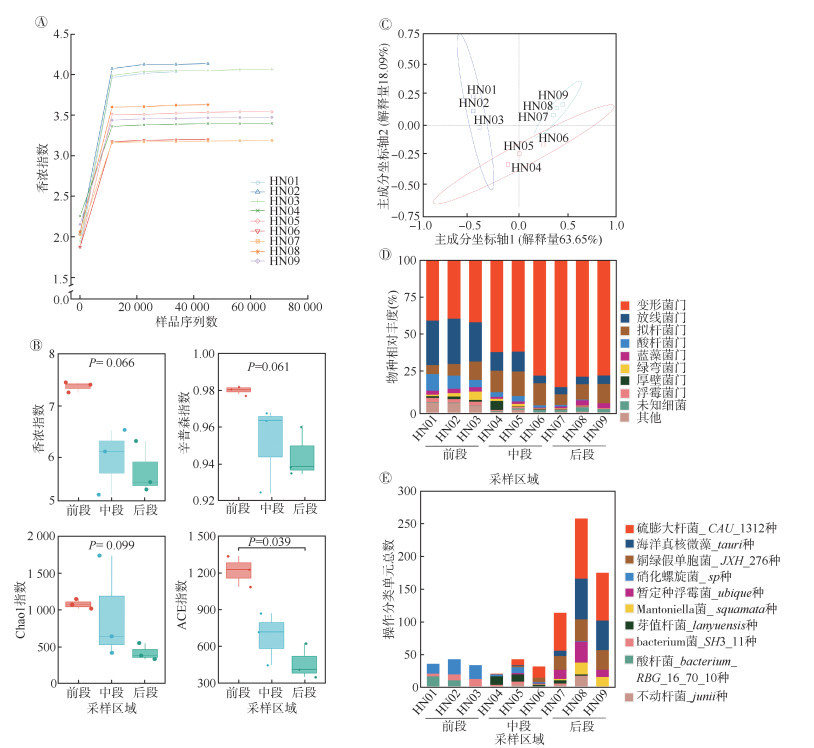

结果1. 微生物群落组成变化:基于香浓指数曲线监测每个样本的测序深度(图 1A),9份水体样本的测序数据量达到平台期,提示能够获得样本中的绝大多数微生物信息。随着河水流经海口市,微生物的α多样性呈现逐渐降低趋势(图 1B),前段的ACE指数高于后段,差异有统计学意义(K-W检验,P < 0.05)。通过PCoA样本中微生物群落组成的差异性(图 1C),结果显示前、中、后段样本分别聚集在各自的置信椭圆中,前两个主成分轴解释了总变异的81.74%,提示前、中、后段的微生物群落结构有明显差异。变形菌门在前、中、后段的BAC中均占据主导地位,中、后段变形菌门相对丰度高于前段(图 1D)。具体而言,在前段区域中变形菌门、放线菌门和拟杆菌门平均相对丰度分别占总细菌的39.3%、28.0%和8.5%;在中段区域中变形菌门的平均相对丰度占比提高至64.9%,而放线菌门则下降至10.0%,另外拟杆菌门的相对丰度占比小幅提升至14.9%;在后段区域变形菌门的平均相对丰度占比进一步提升至78.0%,而放线菌门和拟杆菌门的平均相对丰度占比分别降至4.9%和9.8%。在种水平中微生物的丰度有波动,分布特征与门水平基本一致(图 1E),仅在前段检测到1种放线菌(RBG_16_70_10),而中、后段中则检测到大量的变形菌门,其中包括条件致病菌假单胞菌、不动杆菌和非致病性环境菌株,其丰度在流经城市后显著上升。例如,种水平下的条件致病菌铜绿假单胞菌JXH-276在前段未检出,中段平均OTUs数量为3,后段平均OTUs数量为28。

|

| 注:A:9份水体样本16S rRNA基因全长测序结果获得的香浓指数曲线;B:组间α多样性指数(香浓指数、辛普森指数、Chao1指数和ACE指数)差异性分析;C:HN01~HN03为前段水体、HN04~HN06为中段水体、HN07~HN09为后段水体,通过主坐标分析样本间微生物组成的差异性,椭圆分别表示各组的95%CI;D:门水平细菌的相对丰度;E:种水平细菌除“其他”外丰度最高的10种微生物操作分类单元数量 图 1 海口市南渡江细菌群落构成与差异性分析 |

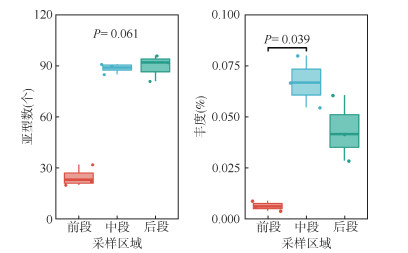

2. 耐药基因的多样性与相对丰度变化:从9份水体样本中共分析13个ARG类型和145个ARG亚型,每份样本的ARGs亚型数量在20~96个之间。其中氨基糖苷类和β-内酰胺类ARGs具有较高的亚型多样性,均为30个ARG亚型。在前段区域,河流受到城市化污染和人为影响较小,ARGs的多样性处于较低水平。在流经城市后,河流中、后段的ARGs亚型数及总丰度均明显升高(K-W检验,多样性P=0.061,丰度P=0.039)。见图 2。总体而言,氨基糖苷类ARGs的丰度最高(0.092%),其次为磺胺类(0.080%)和β-内酰胺类(0.046%)。其中aph(6)和aph(3)分别为氨基糖苷类ARGs贡献了25.7%和19.1%的丰度,sul1和sul2分别为磺胺类ARGs贡献了61.8%和26.7%的丰度,blaOXA和blaCARB分别为β-内酰胺类贡献了41.6%和22.8%的丰度。

|

| 图 2 耐药基因亚型数量及总丰度差异 |

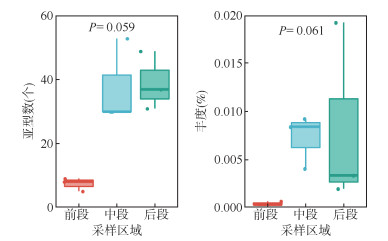

3. VFs的多样性与相对丰度变化:共确定了10个VF类型以及93个亚型。前段的VFs的多样性和丰度均低于中、后段(K-W检验,多样性P=0.059,丰度P=0.061)。见图 3。其中黏附相关因素是丰度最高的VFs(0.014%),其次是效应子输送系统,丰度为0.011%。Ⅳ型菌毛贡献了总黏附相关因素43.2%的丰度。值得注意的是,细菌的分泌系统在HN01~HN04之间处于极低的丰度。同时Ⅵ型分泌系统Hcp岛的HIS-1和HIS-2分别贡献了总效应子输送系统38.2%和34.0%的丰度,并主要分布于中、后段。

|

| 图 3 毒力因子亚型数量及总丰度差异 |

4. ARGs和VFs的扩散方式:细菌在环境中通过MGEs携带的ARGs和VFs在群落中进行横向传播,同时,基于群落演替的垂直传播也使细菌更稳定地获得和扩散ARGs与VFs。为了进一步明确ARGs和VFs在环境中可能的主要扩散方式,基于ARGs、VFs、MGEs和BAC(门水平)的丰度数据集,分别进行普氏分析和曼特尔检验进行一致性和相关性检验。

对于MGEs,共检测到64个亚型,归属于4个MGEs类型,分别为整合酶、插入序列、质粒和转座酶。其中转座酶具有最高的多样性(64个亚型)和丰度(6.48%),其中亚型tnpA贡献了92.8%的丰度。中、后段的MGEs亚型数和总丰度均高于前段K-W检验,亚型数P=0.061,总丰度P=0.066。见图 4。

|

| 图 4 可移动遗传元件亚型数量及总丰度差异 |

通过普氏分析和曼特尔检验计算ARGs、VFs与MGEs及BAC之间的相关性和一致性,得到其偏差平方和(M2)与相关性系数(r),并分析ARGs和VFs在环境中扩散模式(水平传播和垂直传播)。

ARGs和MGEs之间具有显著的一致性(M2=0.205 2,P=0.001)与相关性(r=0.862 5,P=0.002,图 5A)。ARGs与BAC具有显著的一致性(M2=0.327 2,P=0.009)与相关性(r=0.714 3,P=0.017,图 5B)。提示垂直传播和水平传播对于ARGs的扩散起到了几乎相同重要的作用。

|

| 注:MGEs:可移动遗传元件;BAC:细菌群落 图 5 抗生素耐药基因(ARGs)与毒力因子(VFs)的扩散方式 |

对于VFs的扩散方式,VFs与MGEs也显示了良好的一致性(M2=0.192 7,P=0.003)和相关性(r=0.823 7,P=0.002,图 5C)。尽管VFs与BAC显著相关(r=0.691 1,P=0.009),但一致性较差(M2=0.840 4,P=0.305,图 5D)。提示VFs的扩散更多依靠MGEs介导的水平传播。

讨论水生环境中的ARGs和VFs能持续、稳定的存在于环境中,由于其潜在的抗生素耐药和致病性,可能从环境细菌中传播到致病菌中,给人类带来健康风险和经济负担[27-28]。因此,监测和分析水环境中ARGs、MGEs和VFs的多样性、丰度和分布具有公共卫生意义。基于16S rRNA全长测序和宏基因组测序方法,本研究沿海口市南渡江对微生物及其携带的ARGs,MGEs和VFs,以及他们之间的相关性进行了描述和分析。

微生物栖息地环境是影响其群落结构的主要因素[29-30],PCoA显示南渡江流经海口市前、中、后段菌群结构存在差异,考虑不同河段的自然环境因素、海口市区的微生物排出,以及市区排水造成的河段中化学物质的改变综合影响了不同河段的菌群构成。本研究结果显示,在流经城市的中、后段变形菌门的丰度大量增加,尤其是条件致病菌的相对丰度明显增加,这显示了城市排放病原菌对河流菌群构成变化的作用。

本研究结果显示,以低城市化和传统农业为主的前段位于南渡江海口段上游,其ARGs、MGEs和VFs的多样性和丰度均处于非常低的水平。随着河流入城,这些指标的数值大幅提升至较高水平。氨基糖苷类抗生素作为饲料添加剂被大量用于畜禽养殖业[31],在污水、废水或天然水体中被频繁检出[32]。由于此类抗生素基因常随MGEs一起转移,因此在南渡江区域中氨基糖胺类耐药基因的高丰度提示,应注意由于ARGs传播和扩散造成的潜在健康和经济威胁。MGEs被认为是评估河口生态系统ARG污染水平的有力指标[33]。在本研究中tnpA是丰度最高的MGE亚型,tnpA被认为是一种MGE标记基因,与水生环境中的ARGs和金属耐药基因有很强的关联[34]。本研究未检出与高致病性细菌毒素相关的基因,但高丰度的菌毛和分泌系统仍可能在细菌致病性、抗生素耐药和微生物生态位竞争中发挥重要作用。

携带ARGs和VFs的宿主细菌稳定存在于水环境中,不但破坏水体环境,还对周边人群的健康造成严重威胁,其扩散和传播进一步加重了这种危险程度。在抗生素选择压力下,BAC介导的垂直传播是影响ARGs在某些环境中传播的关键驱动因素[35-36]。同时,由MGEs介导的横向转移在细菌间ARGs和VFs的交叉扩散中也发挥了重要作用。

微生物抗生素耐药是一个重大生态问题,其特征是涉及影响人类、动物和环境健康的各种微生物种群的复杂相互作用。同一健康理念通过联合多领域、多学科、多部门等方式,以协调一致的措施解决抗生素耐药造成的健康威胁[37],包括消除抗生素的不当使用,控制工业、农业和生活来源的抗生素污染等措施[38]。针对抗生素及相关问题的环境监测和风险评估,可以更好地了解环境中抗菌药物耐药的选择和传播中的作用,为解决抗生素耐药性问题提供基础数据[39]。通常,医院、污水处理厂等的废水监测受到更多的关注和研究[40-41]。本研究结果提示,河流流经城市前后的微生物组和ARGs组的比较分析,能够展示病原菌和ARGs的改变,也可成为具有公共卫生意义和价值的监测预警指标。

综上所述,本研究基于宏基因组测序技术和16S rRNA全长测序技术,沿海南省海口市南渡江开展了连续样本采集和分析研究,分析了这一区域浮游BAC、ARGs、MGEs和VFs的序列变化和相互关系。本研究结果显示,变形菌门是这一区域的主导细菌类型,而城市化和人为活动如污水排放等影响了微生物栖息地生境,间接改变了BAC的多样性和丰度。氨基糖苷类、磺胺类和β-内酰胺类ARGs是南渡江海口段中丰度最高的3类ARGs。在南渡江流入城市后,ARGs和VFs的多样性和丰度均有所升高,显示了因人为排放造成的影响。而ARGs和VFs的增加会对当地河流生态系统以及人群健康构成潜在威胁。本研究对南渡江海口段水体中ARGs等的监测有助于了解当地水体流经人口密集城市后对一系列与健康相关的因素变化和影响,为进一步治理和解决这一健康风险问题以及环境保护提供参考。

利益冲突 所有作者声明无利益冲突

作者贡献声明 范宇峰:论文撰写、数据整理/分析、样本处理;李臻鹏:数据整理/分析;遇晓杰:现场采样指导;李哲、周海健、张亚淋、甘晓婷、华德:现场样本采集及处理;卢昕:研究设计、论文修改、现场样本采集和指导;阚飙:研究设计、数据分析、论文修改

| [1] |

Xu Y, Guo CS, Luo Y, et al. Occurrence and distribution of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes in the urban rivers in Beijing, China[J]. Environ Pollut, 2016, 213: 833-840. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.054 |

| [2] |

Manaia CM, Macedo G, Fatta-Kassinos D, et al. Antibiotic resistance in urban aquatic environments: can it be controlled?[J]. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 100(4): 1543-1557. DOI:10.1007/s00253-015-7202-0 |

| [3] |

Vaz-Moreira I, Nunes OC, Manaia CM. Bacterial diversity and antibiotic resistance in water habitats: searching the links with the human microbiome[J]. FEMS Microbiol Rev, 2014, 38(4): 761-778. DOI:10.1111/1574-6976.12062 |

| [4] |

Carvalho IT, Santos L. Antibiotics in the aquatic environments: a review of the European scenario[J]. Environ Int, 2016, 94: 736-757. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2016.06.025 |

| [5] |

Qiao M, Ying GG, Singer AC, et al. Review of antibiotic resistance in China and its environment[J]. Environ Int, 2018, 110: 160-172. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2017.10.016 |

| [6] |

Sultan I, Rahman S, Jan AT, et al. Antibiotics, resistome and resistance mechanisms: a bacterial perspective[J]. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 2066. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02066 |

| [7] |

Wright GD. The antibiotic resistome: the nexus of chemical and genetic diversity[J]. Nat Rev Microbiol, 2007, 5(3): 175-186. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1614 |

| [8] |

Rodriguez-Mozaz S, Chamorro S, Marti E, et al. Occurrence of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in hospital and urban wastewaters and their impact on the receiving river[J]. Water Res, 2015, 69: 234-242. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2014.11.021 |

| [9] |

Bengtsson-Palme J, Larsson DGJ. Concentrations of antibiotics predicted to select for resistant bacteria: Proposed limits for environmental regulation[J]. Environ Int, 2016, 86: 140-149. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.015 |

| [10] |

Karkman A, do TT, Walsh F, et al. Antibiotic-resistance genes in waste water[J]. Trends Microbiol, 2018, 26(3): 220-228. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.005 |

| [11] |

Wellington EM, Boxall AB, Cross P, et al. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacteria[J]. Lancet Infect Dis, 2013, 13(2): 155-165. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70317-1 |

| [12] |

Le Page G, Gunnarsson L, Snape J, et al. Integrating human and environmental health in antibiotic risk assessment: A critical analysis of protection goals, species sensitivity and antimicrobial resistance[J]. Environ Int, 2017, 109: 155-169. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2017.09.013 |

| [13] |

邓爱萍. 环境与健康综合监测工作中相关问题探讨[J]. 北方环境, 2011, 23(10): 167-168. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-0370.2011.10.060 Deng AP. Disscussion on integrated monitoring work of environment and health[J]. Northern Environ, 2011, 23(10): 167-168. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-0370.2011.10.060 |

| [14] |

郭怡平. 环境与健康综合监测机制研究[J]. 法制与经济, 2014(2): 129-130. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-0183.2014.02.064 Guo YP. Research on integrated monitoring mechanisms for environment and health[J]. Legal and Economy, 2014(2): 129-130. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1005-0183.2014.02.064 |

| [15] |

叶杉, 耿世洲. 海口市南渡江"一江两岸"发展策略[J]. 水运工程, 2018(8): 34-38. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-4972.2018.08.008 Ye S, Geng SZ. "One river and two banks" development strategy of Nandu River in Haikou[J]. Port Waterway Eng, 2018(8): 34-38. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-4972.2018.08.008 |

| [16] |

Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads[J]. Nat Methods, 2013, 10(10): 996-998. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.2604 |

| [17] |

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community- supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2009, 75(23): 7537-7541. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01541-09 |

| [18] |

Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(D1): D590-596. DOI:10.1093/nar/gks1219 |

| [19] |

Florensa AF, Kaas RS, Clausen PTLC, et al. ResFinder - an open online resource for identification of antimicrobial resistance genes in next-generation sequencing data and prediction of phenotypes from genotypes[J]. Microb Genom, 2022, 8(1): 000748. DOI:10.1099/mgen.0.000748 |

| [20] |

Liu B, Zheng DD, Zhou SY, et al. VFDB 2022: a general classification scheme for bacterial virulence factors[J]. Nucleic Acids Res, 2022, 50(D1): D912-917. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkab1107 |

| [21] |

Li RQ, Yu C, Li YR, et al. SOAP2: an improved ultrafast tool for short read alignment[J]. Bioinformatics, 2009, 25(15): 1966-1967. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp336 |

| [22] |

Desantis TZ, Hugenholtz P, Larsen N, et al. Greengenes, a chimera-checked 16S rRNA gene database and workbench compatible with ARB[J]. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2006, 72(7): 5069-5072. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03006-05 |

| [23] |

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2[J]. Nat Methods, 2012, 9(4): 357-359. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.1923 |

| [24] |

Danecek P, Bonfield JK, Liddle J, et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools[J]. Gigascience, 2021, 10(2): giab008. DOI:10.1093/gigascience/giab008 |

| [25] |

Pärnänen K, Karkman A, Hultman J, et al. Maternal gut and breast milk microbiota affect infant gut antibiotic resistome and mobile genetic elements[J]. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 3891. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-06393-w |

| [26] |

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data[J]. Nat Methods, 2010, 7(5): 335-336. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 |

| [27] |

Li LG, Huang Q, Yin XL, et al. Source tracking of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment-Challenges, progress, and prospects[J]. Water Res, 2020, 185: 116127. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2020.116127 |

| [28] |

Al-Bahry SN, Mahmoud IY, Al-Belushi KI, et al. Coastal sewage discharge and its impact on fish with reference to antibiotic resistant enteric bacteria and enteric pathogens as bio-indicators of pollution[J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 77(11): 1534-1539. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.09.052 |

| [29] |

Ming HX, Fan JF, Liu JW, et al. Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals spatiotemporal dynamics of bacterial community in a heavily polluted estuary, China[J]. Environ Pollut, 2021, 275: 116567. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116567 |

| [30] |

Kegler HF, Lukman M, Teichberg M, et al. Bacterial community composition and potential driving factors in different reef habitats of the Spermonde archipelago, Indonesia[J]. Front Microbiol, 2017, 8: 662. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00662 |

| [31] |

刘清颖. 饲料和环境水中氨基糖苷类药物分析测定研究[D]. 广州: 华南农业大学, 2017. Liu QY. Study on determination of aminoglycoside drugs in feeds and environmental water[D]. Guangzhou: South China Agricultural University, 2017. |

| [32] |

Heuer H, Krögerrecklenfort E, Wellington EMH, et al. Gentamicin resistance genes in environmental bacteria: prevalence and transfer[J]. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 2002, 42(2): 289-302. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb01019.x |

| [33] |

Zhou L, Xu P, Gong JY, et al. Metagenomic profiles of the resistome in subtropical estuaries: Co-occurrence patterns, indicative genes, and driving factors[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2022, 810: 152263. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.152263 |

| [34] |

Zhao YF, Gao JF, Wang ZQ, et al. Responses of bacterial communities and resistance genes on microplastics to antibiotics and heavy metals in sewage environment[J]. J Hazardous Mater, 2021, 402: 123550. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123550 |

| [35] |

Forsberg KJ, Patel S, Gibson MK, et al. Bacterial phylogeny structures soil resistomes across habitats[J]. Nature, 2014, 509(7502): 612-616. DOI:10.1038/nature13377 |

| [36] |

Su JQ, Wei B, Ou-Yang WY, et al. Antibiotic resistome and its association with bacterial communities during sewage sludge composting[J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2015, 49(12): 7356-7363. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b01012 |

| [37] |

Aslam B, Khurshid M, Arshad MI, et al. Antibiotic resistance: one health one world outlook[J]. Front Cell Infect Microbiol, 2021, 11: 771510. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2021.771510 |

| [38] |

Gaze WH, Krone SM, Larsson DG, et al. Influence of humans on evolution and mobilization of environmental antibiotic resistome[J]. Emerg Infect Dis, 2013, 19(7): e120871. DOI:10.3201/eid1907.120871 |

| [39] |

Huijbers PMC, Blaak H, de Jong MCM, et al. Role of the environment in the transmission of antimicrobial resistance to humans: a review[J]. Environ Sci Technol, 2015, 49(20): 11993-12004. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.5b02566 |

| [40] |

Hassoun-Kheir N, Stabholz Y, Kreft JU, et al. Comparison of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes abundance in hospital and community wastewater: A systematic review[J]. Sci Total Environ, 2020, 743: 140804. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140804 |

| [41] |

Manaia CM, Rocha J, Scaccia N, et al. Antibiotic resistance in wastewater treatment plants: Tackling the black box[J]. Environ Int, 2018, 115: 312-324. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2018.03.044 |

2023, Vol. 44

2023, Vol. 44