文章信息

- 章琦, 王玲玲, 柏如海, 党少农, 颜虹.

- Zhang Qi, Wang Lingling, Bai Ruhai, Dang Shaonong, Yan Hong.

- 育龄妇女生育间隔与活产单胎新生儿出生体重的关联分析

- Effect of interpregnancy interval of childbearing aged women on birth weight of single live birth neonates

- 中华流行病学杂志, 2018, 39(3): 317-321

- Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2018, 39(3): 317-321

- http://dx.doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.03.013

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2017-07-29

2. 710061 西安交通大学医学部公共卫生学院全球健康研究院

2. Global Health Institute, Health Science Center of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an 710061, China

生育间隔(IPI)是指妇女上次怀孕终止日期与本次怀孕末次月经之间的时间[1],过短或过长均可对母婴健康结局造成不良影响。新生儿出生体重是衡量围生结局的重要指标之一。低出生体重儿易发生宫内窘迫,死亡风险大,且成年后患糖尿病、心血管疾病的风险增加[2-3]。出生体重过高易引发难产,导致产妇产后出血,使软产道撕伤明显,增加新生儿产伤、窒息的风险[4],成年后患2型糖尿病、肥胖、心血管疾病等代谢综合征的风险增加[5-6]。研究发现IPI过长或过短均可导致低出生体重、早产、围生儿死亡等不良围生结局[1, 7]。目前IPI与巨大儿关系的研究甚少。为此本研究在2010-2013年陕西省出生缺陷现况及其危险因素调查中应用多重线性回归及分位数回归,探讨育龄妇女IPI对新生儿出生体重的影响。

对象与方法1.研究对象:为2010-2013年陕西省曾怀孕且明确结局的15~49岁育龄妇女及其生育子女,均为当地常住人口,排除初产妇、末次妊娠结局非单胎、非活产、妊娠结局不明确、既往孕产史不详的孕妇。

2.研究方法:采用分层多阶段随机整群抽样方法,按城乡比例,并考虑人口密集度和生育水平,随机抽取10个城区和20个县,抽取的样本县中每县随机抽取6个乡,每乡随机抽取6个村,每村随机调查30名符合条件的研究对象。抽取的样本区中每区随机抽取3个街道办事处,各随机抽取6个社区(居委会),再各随机调查60名符合条件的研究对象。采用面对面问卷调查方式收集育龄妇女社会人口学信息、生活行为与心理状况、疾病史与用药、环境危险因素、职业危险因素、生育史与孕产期保健、家族遗传史等资料。调查员由西安交通大学硕士研究生和本科生担任,均经严格统一培训并考核合格。现场调查中由专人及时审核问卷,问卷录入阶段核对数据并进行逻辑检查,发现有问题的数据及时核查原始记录。

3.相关定义:IPI定义为2次连续分娩之间的间隔时间减去第2胎儿的孕周,以“月”对IPI进行度量(每13周换算为3个月)[8]。按生育间隔长度依次分为8组(<12、12~17、18~23、24~35、36~47、48~59、60~119、≥120个月),由于IPI为18~23个月时,发生不良妊娠结局的风险最低[9-10],该组为参照组。低出生体重儿指出生1 h内体重<2 500 g的新生儿;巨大儿指出生1 h内体重≥4 000 g的新生儿。家庭经济参数中家庭校正成年人数=家庭成年人数+0.5×家庭子女数,家庭人均年收入=家庭全年总收入/家庭校正成年人数,根据四分位数法按居住地分别计算城市和农村人口人均年收入,将家庭经济状况分为贫穷、中等和富裕。

4.统计学分析:利用EpiData 3.1软件建立数据库和纠错程序,并对数据进行双录入。统计学分析采用SAS 9.4软件。计数资料采用相对比指标描述,计量资料采用x±s描述,率的比较用χ2检验,均数的比较用t/F检验。采用多重线性回归及分位数回归模型分析IPI与活产单胎新生儿出生体重的关系,同时控制混杂因素。分位数回归使用SAS 9.4软件中的PROC QUANTREG过程,运用内点算法(interior point method)分别拟合出生体重处于不同百分位点(q=0.05,0.10,0.15,0.20,…,0.95)的分位数回归模型,本文表格中只选取部分百分位点的结果(文中的百分位点均以小数表示,如q=0.05表示应变量处于第5百分位点)。

结果1.一般情况:调查期间怀孕且结局明确的育龄妇女30 027人,获得活产单胎29 266例,剔除初产妇14 402例、既往生育史不详者1 375例、出生体重不明确者426例,对13 063名育龄妇女及其子女进行分析。其中陕南地区2 523人,陕北地区6 878人,关中地区3 662人;99.33%(12 976人)为汉族;86.56%(11 307人)为农村户籍;23.63%(3 087人)接受过高中及以上教育;74.27%(9 702人)职业为农民;新生儿56.45%(7 374人)为男性;母亲年龄(30.60±4.98)岁,怀孕(2.30±0.63)次;城市人口人均年收入为26 081.03元,农村为10 483.92元。

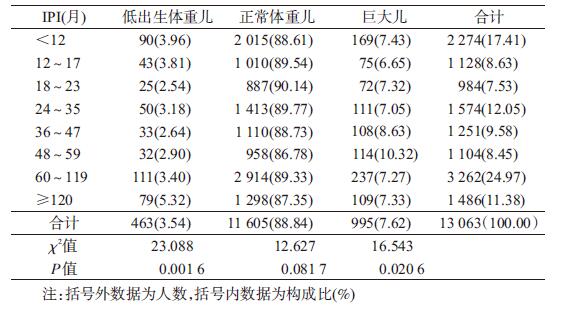

2.出生体重及母亲IPI现状:13 063名新生儿出生体重为(3 276.73±470.71)g,低出生体重儿发生率为3.54%,巨大儿发生率为7.62%。母亲IPI<12个月的新生儿有2 274人(17.41%),≥120个月的有1 486人(11.38%)。见表 1。

3.出生体重影响因素分析:

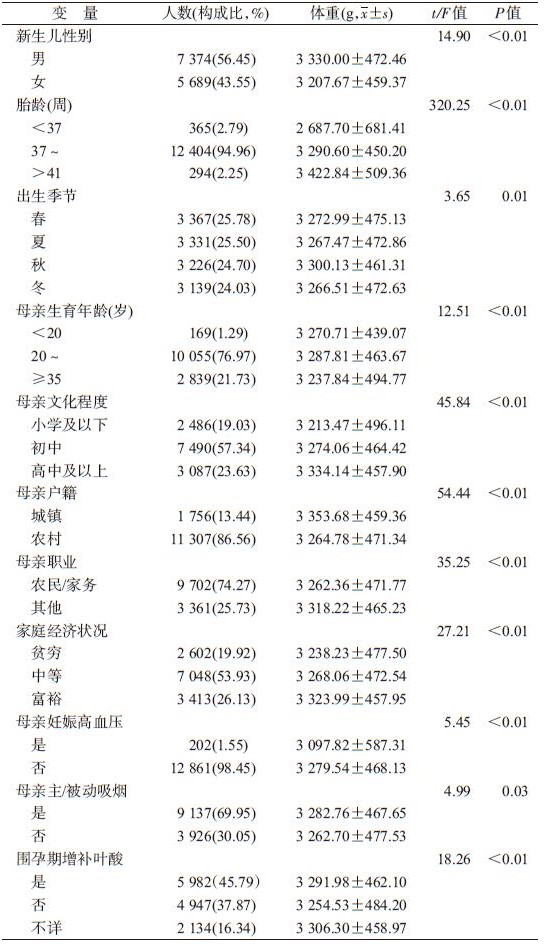

(1)单因素分析:分析显示,新生儿性别、胎龄、出生季节及母亲生育年龄、文化程度、户籍、职业、家庭经济状况、妊娠高血压、主/被动吸烟、围孕期增补叶酸共11个因素对新生儿出生体重的影响有统计学意义(表 2)。

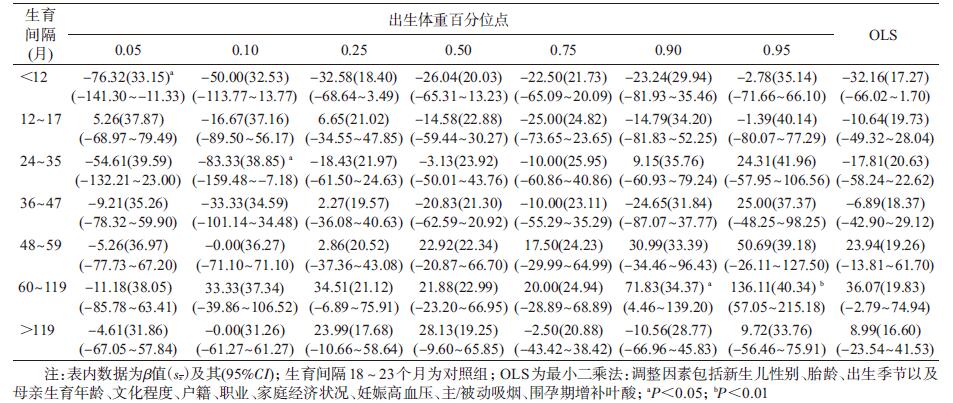

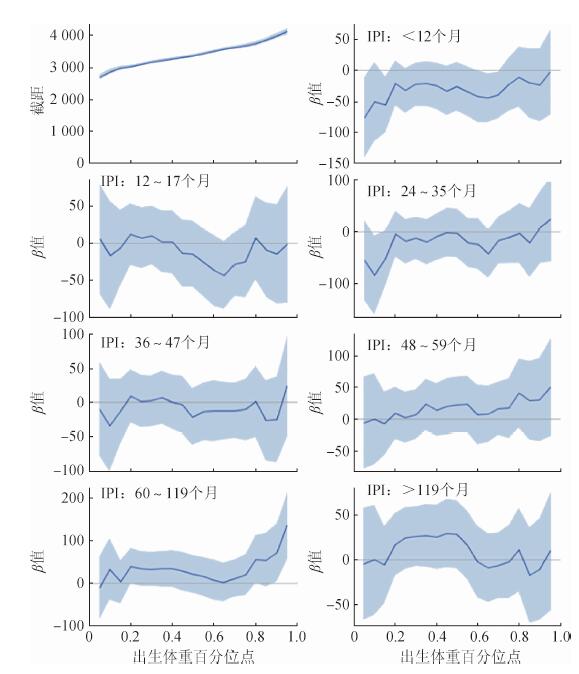

(2)多因素分析:将出生体重和IPI分别以因变量和自变量纳入多重线性回归及分位数回归模型,并控制单因素分析中有统计学意义的因素。多重线性回归结果显示,在控制其他混杂因素后,不同IPI对新生儿出生体重的差异无统计学意义;而分位数回归结果表明,与IPI为18~23个月相比,其他组对出生体重处于不同百分位点的新生儿影响不一致,当出生体重处于极低百分位点时(q=0.05),IPI<12个月新生儿出生体重显著低于IPI为18~23个月者,随着出生体重百分位点的增加,差异逐渐减小;当出生体重处于较低百分位点时(q=0.10),IPI处于24~35个月新生儿出生体重显著低于IPI为18~23个月者,随着出生体重百分位点增加,差异逐渐趋于稳定。表明母亲IPI小对体重较轻的新生儿影响更大。当出生体重q≥0.95时,IPI处于60~119个月之间者出生体重显著高于IPI为18~23个月者,且随着出生体重的百分位点增加,差异的幅度逐渐增加,表明母亲IPI大对体重较重的新生儿影响更大。其他组与参照组相比,差异均无统计学意义(表 3、图 1)。

|

| 注:阴影部分为β值及其95%CI;IPI:18~23个月为参照组 图 1 生育间隔(IPI)对新生儿不同百分位点出生体重的影响 |

有研究表明[9-10],当IPI处于18~23个月时,其发生不良妊娠结局的风险最低,包括低出生体重、早产、小于胎龄儿等。因此,本研究把该分组作为参照组。结果显示,基于最小二乘法的传统线性回归与分位数回归两种方法所得结论不一致。传统线性回归的结果表明,在控制了混杂因素后,不同IPI组与参照组相比,新生儿出生体重差异无统计学意义。分位数回归方法可以研究影响因素与不同百分位数上的因变量的关系,而传统线性回归只能研究影响因素与因变量平均水平之间的关系[11]。分位数回归更关注分布两端的低出生体重儿及巨大儿出生体重受自变量影响的情况。本文结果发现,IPI过短或过长均可对胎儿生长发育造成一定影响。

本研究还显示,当IPI<12个月和IPI处于24~35个月时与新生儿低出生体重显著相关。国外相关研究表明[12-13],当IPI<12个月时,其新生儿发生早产、低出生体重、小于胎龄儿的风险显著增加。可能的原因是孕期和哺乳期紧密连接使母体内营养衰竭,没有足够的时间恢复精力以及营养维持随后胎儿的生长发育[14],例如促进胎儿生长发育的叶酸被母体吸收至少需要6个月[15]。另外,IPI过短可增加母亲心理压力,易导致早产、低出生体重儿等不良妊娠结局[16]。而IPI处于60~119个月与巨大儿显著相关。有研究发现,当IPI增加,母体孕期的BMI随之增加[17],且IPI长,易引起孕妇妊娠糖尿病[7],后者是导致巨大儿发生的重要危险因素之一[18]。IPI是一个可控制的危险因素,故控制IPI对于获得良好的围生结局具有重要的意义。

本研究未将前次怀孕结局进一步分类,而前次怀孕活产和终止妊娠可能对本次怀孕胎儿生长发育造成不同的影响,并对结果可能造成一定的偏倚;由于本次属于横断面调查,收集的为回顾性信息,可能存在回忆偏倚。

利益冲突: 无

| [1] | Mignini LE, Carroli G, Betran AP, et al. Interpregnancy interval and perinatal outcomes across Latin America from 1990 to 2009:a large multi-country study[J]. BJOG, 2016, 123(5): 730–737. DOI:10.1111/1471-0528.13625 |

| [2] | Meier JJ. Linking the genetics of type 2 diabetes with low birth weight:a role for prenatal islet maldevelopment?[J]. Diabetes, 2009, 58(6): 1255–1256. DOI:10.2337/db09-0225 |

| [3] | Arnold LW, Hoy WE, Wang ZQ. Low birth weight and large adult waist circumference increase the risk of cardiovascular disease in remote indigenous Australians-an 18 year cohort study[J]. Int J Cardiol, 2015, 186: 273–275. DOI:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.209 |

| [4] | Ezegwui HC, Ikeako LC, Egbuji C. Fetal macrosomia:obstetric outcome of 311 cases in UNTH, Enugu, Nigeria[J]. Niqer J Clin Pract, 2011, 14(3): 322–326. DOI:10.4103/1119-3077.86777 |

| [5] | Wang Y, Gao E, Wu J, et al. Fetal macrosomia and adolescence obesity:results from a longitudinal cohort study[J]. Int J Obes, 2009, 33(8): 923–928. DOI:10.1038/ijo.2009.131 |

| [6] | Ong KK. Early determinants of obesity[J]. Endocr Devel, 2010: 53–61. DOI:10.1159/000316897 |

| [7] | Hanley GE, Hutcheon JA, Kinniburgh BA, et al. Interpregnancy interval and adverse pregnancy outcomes:an analysis of successive pregnancies[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2017, 129(3): 408–415. DOI:10.1097/AOG.0000000000001891 |

| [8] |

杜明钰, 马润政, 王明芳, 等. 昆明地区妇女生育间隔对妊娠结局的影响[J]. 中国妇幼保健, 2015, 30(20): 3342–3344.

Du MY, Ma RZ, Wang MF, et al. Effect of interpregnancy interval of the women of childbearing age on pregnancy outcome in Kunming[J]. Chin J Matern Child Health Care, 2015, 30(20): 3342–3344. DOI:10.7620/zgfybj.j.issn.1001-4411.2015.20.05 |

| [9] | Zhu BP, Rolfs RT, Nangle BE, et al. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on perinatal outcomes[J]. N Engl J Med, 1999, 340(8): 589–594. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199902253400801 |

| [10] | Zhu BP, Le T. Effect of interpregnancy interval on infant low birth weight:a retrospective cohort study using the Michigan Maternally Linked Birth Database[J]. Matern Child Health J, 2003, 7(3): 169–178. DOI:10.1023/A:1025184304391 |

| [11] |

任琳, 裴磊磊, 颜虹, 等. 陕西省汉中地区农村男性居民吸烟行为与肥胖的关系[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2012, 33(9): 907–911.

Ren L, Pei LL, Yan H, et al. Relationships between smoking behavior and obesity in men from 9 rural districts of Hanzhong in Shaanxi province[J]. Chin J Epidemiol, 2012, 33(9): 907–911. DOI:10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2012.09.007 |

| [12] | Mahande MJ, Obure J. Effect of interpregnancy interval on adverse pregnancy outcomes in northern Tanzania:a registry-based retrospective cohort study[J]. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth, 2016, 16(1): 140. DOI:10.1186/s12884-016-0929-5 |

| [13] | Ball SJ, Pereira G, Jacoby P, et al. Re-evaluation of link between interpregnancy interval and adverse birth outcomes:retrospective cohort study matching two intervals per mother[J]. BMJ, 2014, 349: g4333. DOI:10.1136/bmj.g4333 |

| [14] | Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Castaño F, et al. Effects of birth spacing on maternal, perinatal, infant, and child health:a systematic review of causal mechanisms[J]. Stud Fam Plann, 2012, 43(2): 93–114. DOI:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2012.00308.x |

| [15] | Merklinger-Gruchala A, Jasienska G, Kapiszewska M. Short interpregnancy interval and low birth weight:A role of parity[J]. Am J Hum Biol, 2015, 27(5): 660–666. DOI:10.1002/ajhb.22708 |

| [16] | McKinney D, House M, Chen AM, et al. The influence of interpregnancy interval on infant mortality[J]. Am J Obset Gynecol, 2017, 216(3): 316.e1–316.e9. DOI:10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.018 |

| [17] | Villamor E, Cnattingius S. Interpregnancy weight change and risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes:a population-based study[J]. Lancet, 2006, 368(9542): 1164–1170. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69473-7 |

| [18] | Retnakaran R, Ye C, Hanley AJG, et al. Effect of maternal weight, adipokines, glucose intolerance and lipids on infant birth weight among women without gestational diabetes mellitus[J]. CMAJ, 2012, 184(12): 1353–1360. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.111154 |

2018, Vol. 39

2018, Vol. 39