b Frontier Institute of Science and Technology and Interdisciplinary Research Centre of Frontier Science and Technology, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, China;

c School of Pharmacy, Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’an 710049, China

Carbo- and heterocycles are fundamental structures in numerous natural products and bioactive compounds, particularly in medicinal chemistry [1,2]. Over 85% of biologically active molecules contain heterocycles, underscoring their significance in synthetic research [3,4]. Radical cycloaddition reactions have emerged as particularly valuable tools in this context. The discovery of the triphenylmethyl radical by Gomberg in 1900 marked the beginning of free radical chemistry [5]. Since then, radical reactions have garnered significant attention due to their high tolerance for functional groups, mild reaction conditions, and the presence of non-charged intermediates [6]. These features make radical reactions highly attractive for synthetic chemists. Compared to traditional methods, radical reactions offer several advantages, including broader functional group compatibility, gentler reaction conditions, and simpler pathways with fewer byproducts [7-22].

Cycloaddition reactions represent a crucial class of organic chemical reactions, renowned for their efficiency in forming carbon-carbon bonds without the need for nucleophiles or electrophiles [23-34]. The Diels-Alder reaction, a [4 + 2] cycloaddition, is perhaps the most well-known example. These reactions are not only atom-efficient but also offer high levels of convergence and stereoselectivity, making them highly desirable for preparative chemistry. Their versatility is further demonstrated through applications in developing photoresponsive materials and membranes [35,36]. Cycloaddition reactions are primarily employed to construct carbocycles and heterocycles of various sizes, which are frequently found in natural products with intriguing biological properties and potential medicinal applications. Given these advantages, significant efforts have been dedicated to developing novel synthetic methods using radical cycloaddition strategies. These reactions are increasingly utilized in diversity-oriented synthesis to enhance the structural diversity and complexity of small molecules. Consequently, the collection of chemical reactions for constructing cyclic compounds has become an indispensable toolbox for synthetic chemists [37,38]. Highlighting innovative advancements and identifying areas for improvement are essential to provide more efficient pathways for synthesizing natural product molecules and to inspire further research into new synthetic methodologies.

This review examines recent developments and applications of radical cycloaddition reactions (RCRs), including visible light-induced radical photocycloaddition reactions (RPCRs), transition metal-catalyzed approaches, and small molecule-catalyzed methods. As outlined in Scheme 1, this review is sub-organized by the type of cycloaddition reactions, such as [2 + 2], [3 + 2], [4 + 2], and [3 + 3] cycloadditions, covering the product scope and mechanisms for various methods. It concludes by discussing challenges, future directions, and emerging trends in radical cycloaddition chemistry.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Types of cycloaddition covering this review. | |

2. Visible light induced RPCRS 2.1. [2 + 2] cycloaddition

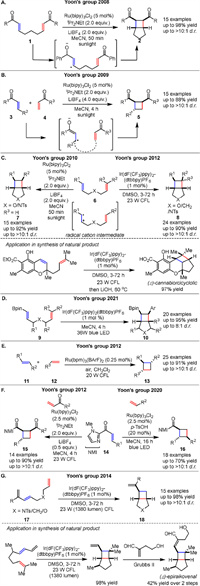

The Yoon group has been at the forefront of radical photocycloaddition reactions, developing several elegant [2 + 2] cycloaddition methods using visible light photocatalysis, significantly expanding the scope and applicability of this synthetic strategy. In 2008, they demonstrated the efficient visible light photocatalysis of [2 + 2] cycloadditions of bis(enone) 1 using Ru(bpy)3Cl2 as a photocatalyst, achieving high yields and stereoselectivity of cyclobutane-containing bicyclic dione 2. Importantly, the light source used in this procedure was a standard 275 W floodlight, without any specialized high-pressure UV photolysis apparatus (Scheme 2A) [39]. In 2009, they focused on crossed intermolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions of acyclic enones 3 and 4, overcoming the challenge of intermolecular photochemical [2 + 2] cycloadditions by using a Ru(bpy)3Cl2-catalyzed system via a radical mechanism. Strained four-membered rings 5 were constructed with excellent chemo- and stereoselectivity (Scheme 2B) [40]. In 2010, they introduced a photooxidative approach for intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions of electron-rich olefins 6 using Ru(bpy)32+, enabling the synthesis of cyclobutanes 7 from styrenes (Scheme 2C left) [41]. Extending this work, in 2012, they explored energy transfer mechanisms for this intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions of styrenes 6 using iridium complexes, demonstrating high yields and broad substrate scope (Scheme 2C right) [42]. Following the same mechanism, years later, they also developed intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions of vinyl boronate esters 9 and found that simple vinyl boronates readily reacted with excited-state triplet alkenes that are generated by visible light triplet sensitization (Scheme 2D) [43]. A crossed [2 + 2] cycloadditions of styrenes 11 and 12 using visible light photocatalysis with carefully tuned ruthenium photocatalysts was reported by the Yoon group in 2012. A concise synthesis of a complex natural product (cannabiorcicyclolic acid) was also demonstrated (Scheme 2E) [44]. After this, they reported the use of cleavable redox auxiliaries to facilitate [2 + 2] cycloadditions of enones 14, expanding the scope of substrates that can be used (Scheme 2F) [45,46]. The [2 + 2] cycloaddition of 1,3-dienes 17 was then demonstrated by the Yoon group, using visible light and transition metal complexes, reflecting the versatility and functional group tolerance of this method. Moreover, highlighting the ability to perform this complex [2 + 2] cycloaddition, they developed a concise and modular synthesis of the cyclobutane-containing natural product (±)-epiraikovenal (Scheme 2G) [47]. Together, these studies showcased the power of visible light photocatalysis in enabling a wide range of [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions, from enones to styrenes and dienes, and highlight the potential for further development in this field.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Visible light-induced intermolecular and intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloadditions of olefins. | |

In 2014, the Yoon group presented a dual-catalysis approach to enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloadditions between 19 and 20 using visible light to produce cyclobutene (23, 24). The authors describe a method that eliminates racemic background reactions, a major challenge in asymmetric photocycloadditions. The strategy involves a combination of a visible light-absorbing transition-metal photocatalyst and a stereocontrolling Lewis acid cocatalyst. This dual-catalyst system via radical mechanism enables broader scope, greater stereochemical flexibility, and better efficiency than previously reported methods (Scheme 3). The mechanism of this enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reaction involves the activation of Ru(bpy)32+ by visible light, which then reduces the aryl enone substrate in the presence of a Lewis acid (Eu(OTf)3) and a chiral ligand. The resulting radical anion intermediate 25 reacts with an aliphatic enone 20 to form a cyclobutane radical intermediate, which recombines to produce the desired cyclobutane product. The chiral Lewis acid cocatalyst, composed of Eu(OTf)3 and the chiral ligand, controls the stereochemistry of the reaction, ensuring high enantioselectivity. This dual-catalyst system effectively eliminates racemic background reactions, providing a highly enantioselective method for the synthesis of cyclobutanes [48].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition via dual catalysis. | |

In 2017, the Yoon group explored enantioselective crossed photocycloadditions of styrenic olefins 27 via Lewis acid catalyzed triplet sensitization for synthesizing highly enantioenriched diarylcyclobutanes 29 by photocycloaddition of 2’-hydroxychalcones 26 with various styrene 27 coupling partners. The key mechanistic feature is the dramatic lowering of the singlet-triplet gap of the chalcone upon Lewis acid coordination, enabling efficient triplet energy transfer from a Ru(bpy)32+ photosensitizer (Scheme 4). The reaction is highly enantioselective and can tolerate a wide range of substituents on both the chalcone and styrene partners. The utility of this reaction is demonstrated through the direct synthesis of a representative norlignan cyclobutane natural product [49].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 4. Enantioselective [2 + 2] crossed photocycloaddition of 2’-hydroxychalcones and olefin. | |

In 2022, the Yoon group presented a novel strategy for enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloadditions of acyclic vinylpyridines 33 through ternary complex formation and an uncontrolled sensitization mechanism. The authors describe a method where both a chiral catalyst-associated vinylpyridine and a nonassociated, free vinylpyridine substrate can be sensitized by an IrⅢ photocatalyst. Despite indiscriminate triplet energy transfer from the excited state photosensitizer to both on- and off-catalyst species, high levels of diastereo- and enantioselectivity are achieved through a preferred, highly organized transition state (Scheme 5A). This mechanistic paradigm is distinct from current approaches, which typically focus on suppressing off-catalyst pathways. The study demonstrates the successful application of this method to a variety of substrates, including those with dense stereochemical complexity and additional nitrogen-based functionalities, achieving high enantiomeric excess (up to 96% ee) and good yields (up to 99%) [50]. In the same year, they reported a cooperative stereoinduction in asymmetric photocatalysis, specifically focusing on the [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of vinylpyridines 36 and alkene 37. The authors describe a tandem chiral photocatalyst/Brønsted acid strategy that enables highly enantioselective photocycloadditions. A significant finding is the observation of different reaction rates and enantioselectivities between matched and mismatched chiral catalyst pairs, which is attributed to their cooperative behavior in a transient excited-state assembly (Scheme 5B). The study demonstrates that the chirality of the Brønsted acid and the IrⅢ photocatalyst play a crucial role in determining the enantioselectivity of the reaction. The matched catalyst pair (Δ-[Ir] with (R)-CPA) provides higher yields and enantiomeric excess compared to the mismatched pair (Λ-[Ir] with (R)-CPA) [51]. Soon after, they introduced an enantioselective [2π + 2σ] photocycloaddition enabled by Brønsted acid catalyzed chromophore activation. The authors demonstrate that Brønsted acid catalysis of C-acyl imidazoles enables highly enantioselective [2π + 2σ] photocycloadditions, which are useful for synthesizing bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 43 and other strained small-ring structures relevant to pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. The study shows that increasing the steric bulk of the imidazole substituent inhibits the formation of undesirable dimers, leading to higher yields of the desired bicyclohexane products (43). The imidazole auxiliary can be cleaved to provide useful synthetic handles without erosion of enantiomeric purity (Scheme 5C). This work highlights the versatility of chiral Brønsted acid catalysis in asymmetric photochemical reactions and its potential for practical applications in synthesizing enantiopure libraries of saturated bicyclic motifs [52].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 5. Enantioselective intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloadditions. | |

In 2018, Megger and co-workers reported a novel method for catalytic asymmetric dearomatization by visible-light-activated [2 + 2] photocycloaddition using benzofurans 44 yielding chiral tricyclic structures 47 with up to four stereocenters, including quaternary centers. The benzofurans are functionalized at the 2-position with an N-acylpyrazole moiety that coordinates with a chiral-at-rhodium Lewis acid catalyst 46. The reaction involves the formation of a reactant complex 48 that absorbs blue light, undergoes intersystem crossing (ISC) to a triplet state 50, and reacts with an alkene substrate 45 to generate a 1,4-biradical intermediate 51. This intermediate recombines to form the desired photocycloaddition product 47. Computational modeling reveals that the regioselectivity is influenced by the stability of the 1,4-biradical intermediate 51, with the heteroatom in the heterocycle playing a key role in regiocontrol (Scheme 6) [53]. The study demonstrates high enantioselectivity (up to 99% ee) and good functional group tolerance, highlighting the potential of this method for synthesizing complex chiral structures.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 6. Rh-catalyzed, asymmetric dearomatization of benzofurane by visible-light activated [2 + 2] photocycloadditions. | |

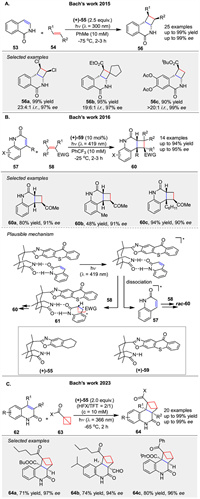

In 2015, the Bach group introduced an enantioselective [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of isoquinolones 53 with alkenes 54, utilizing a chiral template 55 to achieve high enantioface differentiation [54]. This method enabled the synthesis of various functionalized cyclobutanes 56 with excellent yields and enantioselectivities (up to 99% ee) (Scheme 7A). Subsequently, they described an enantioselective intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of 2(1H)-quinolones 57 with electron-deficient alkenes 58, employing a chiral thioxanthone catalyst 59 (Scheme 7B) [55]. This reaction exhibited high regio- and diastereoselectivity, yielding cyclobutane products 60 with significant enantiomeric excess (up to 95% ee). The chiral template enhanced substrate solubility and enantiocontrol through two-point hydrogen bonding between the quinolone and the catalyst, facilitating efficient energy transfer and high enantioface differentiation. The reaction likely proceeds via a triplet state of the quinolone, with the alkene 58 reacting at carbon atom C3, leading to a 1,4-diradical intermediate 61 and product formation. Continuing their work, they reported the first enantioselective [2π + 2σ] photocycloaddition reactions of 1-substituted bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes 63 with 2(1H)-quinolones 62, using a chiral complexing agent 55. This reaction resulted in the formation of chiral bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane skeletons 64 with high enantiomeric excess (up to 99% ee) (Scheme 7C) [56].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 7. Enantioselective intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition using chiral thioxanthone catalyst. | |

Bach and colleagues have then reported on the visible light-induced [2 + 2] radical photocycloaddition of β-nitrostyrenes 65 to various olefins 66, demonstrating that these reactions can be efficiently conducted at λ = 419 nm in CH2Cl2 solvent, yielding cyclobutanes 67 with moderate to good yields (up to 87%) (Scheme 8A left) [57]. This work has been further extended to include 65, where optimized conditions and a broader range of substrates were explored, achieving yields up to 88% (Scheme 8A right) [58]. In a related study, the intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of α,β-unsaturated sulfones 69 and alkene 70 was achieved at λ = 300 nm, yielding 2-aryl-1-sulfonyl-substituted cyclobutanes 71 with yields up to 99% (Scheme 8B) [59]. These studies collectively highlight the formation of a triplet 1,4-diradical intermediate as a key mechanistic step, supported by the observation of side products and triplet sensitization experiments. The influence of Lewis acids and triplet sensitizers on reaction efficiency and selectivity was also explored, with varying success depending on the substrate and reaction conditions.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 8. Visible light-induced intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of β-nitrostyrenes and α,β-unsaturated sulfones with alkenes. | |

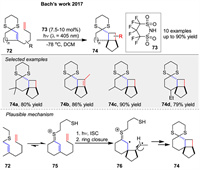

In 2017, the same group reported a Brønsted acid-catalyzed intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of enone dithianes 72 under visible light irradiation (λ = 405 nm). The reaction relies on the formation of colored thionium ions 75, which are intermediates in the catalytic cycle and can be excited in the visible region. The study demonstrates that the presence of a Brønsted acid 73 is crucial for the success of the reaction, enabling the formation of cyclobutanes 74 in high yields (up to 90%). The mechanism likely involves the formation of a thionium ion 75 upon protonation of the dithiane 72, which then undergoes intersystem crossing to a triplet state, leading to the formation of a 1,4-diradical intermediate 76 and subsequent ring closure (Scheme 9) [60].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 9. Brønsted acid-catalyzed intramolecular [2+2] photocycloaddition. | |

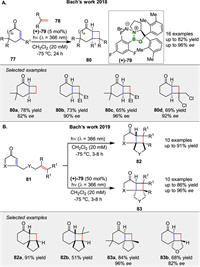

In consecutive years, Bach and colleagues have made significant strides in developing enantioselective intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions of cyclic enones 77, exploring the role of Lewis acids in achieving high enantioselectivity and their applications in natural product synthesis. In the intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of cyclic enones 77 with olefins 78 using a chiral oxazaborolidine-AlBr3 Lewis acid complex 79 to achieve high enantioselectivity (Scheme 10A) [61].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 10. Enantioselective intermolecular and intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloaddition of enones. | |

In the intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of alkenyl cycloalkenones 81, showed that the enantioselectivity is strongly influenced by the aryl group on the oxazaborolidine 79 (Scheme 10B) [62]. DFT calculations suggest that dispersion forces may affect the binding mode and enantioselectivity. Both studies emphasize the utility of Lewis acids in enhancing reaction selectivity and provide valuable insights for the synthesis of complex natural products.

An enantioselective synthesis of chiral cyclobutanecarbaldehydes 86 via [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of chiral eniminium ion 84 with alkene 85 using Ru(bpz)3(PF6)2 as catalysts was reported by Bach group in 2020. The reaction yields 86 with high selectivity (up to 74% yield, up to 96:4 er) (Scheme 11). Mechanistic studies using laser flash photolysis showed that the reaction proceeds via triplet-energy transfer from the ruthenium catalyst to the eniminium ion 84, which is then quenched by the olefin 85 to form the product. Upon visible light irradiation, the ruthenium complex transfers energy to the eniminium ions 84, exciting them to a reactive triplet state 87. These excited ions 87 then react with olefins 85 to form cyclobutane intermediates 89, which upon hydrolysis yield chiral cyclobutanecarbaldehydes 86. The reaction is highly enantioselective due to the influence of a chiral secondary amine cocatalyst. The study explores catalytic enantioselective reactions using a chiral secondary amine co-catalyst, demonstrating the potential for this method in synthesizing chiral cyclobutanecarbaldehydes 86 [63].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 11. Synthesis of chiral cyclobutanecarbaldehydes via [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of chiral eniminium ions with alkene. | |

In 2022, Bach group reported a visible light-driven intramolecular crossed [2 + 2] photocycloaddition to synthesize bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 91, a valuable motif in medicinal chemistry. The reaction leverages triplet energy transfer from an iridium photosensitizer to styrene derivatives 90, leading to the formation of these bridged scaffolds with good to high yields (up to 99%). The mechanism likely involves energy transfer from the excited iridium catalyst to the substrate 90, forming a triplet intermediate 90* that cyclizes in a 5-endo mode to produce the desired product 91 (Scheme 12A). This method enables the synthesis of a variety of 1,4-disubstituted bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 91, which can be further functionalized, highlighting its potential for constructing complex and rigid scaffolds [64]. An enantioselective crossed intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of 2-(alkenyloxy)cyclohex-2-enones 92 using a chiral rhodium Lewis acid catalyst 46 was presented by Bach group in 2022, achieving high enantioselectivity (80%-94% ee) under visible light (Scheme 12B) [65]. The mechanism involves the formation of a 1,4-diradical intermediate that forms the complex cyclobutane bridged skeletons 93.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 12. Ir-catalyzed photochemical intramolecular crossed [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of styrene derivatives. | |

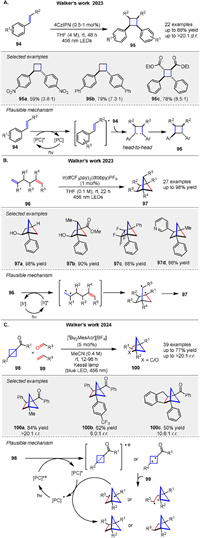

Walker group discovered a visible-light organophotocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction involving electron-deficient styrenes 94, in 2022. They found that an organic cyanoarene photocatalyst (4CzIPN) can efficiently catalyze the formation of cyclobutanes 95 from electron-deficient styrenes with good functional group tolerance. The study explores the scope of the reaction, demonstrating its applicability to a range of electron-deficient substituents and achieving both homodimerizations and intramolecular [2 + 2] cycloadditions. The mechanism likely involves an energy-transfer pathway, supported by experiments showing reduced yields in the presence of a triplet quencher (Scheme 13A) [66]. This method offers a sustainable and cost-effective alternative to traditional transition-metal-based catalysts, expanding the toolkit for synthetic chemists working with cyclobutane derivatives. Following this, a visible light-mediated photocatalytic [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction that provides access to polysubstituted bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes (BCHs) 98 from 97. They developed a protocol using [Ir{dF(CF3)ppy}2(dtbbpy)]PF6 as a photocatalyst to synthesize BCHs 98 with distinct substitution patterns, including structures that can serve as bioisosteres for ortho-, meta-, and polysubstituted benzenes. The method is operationally simple and tolerates a broad range of functional groups (Scheme 13B) [67]. Key findings include the preparation of BCHs with various substituents, such as esters, alcohols, and boronate esters, in high yields. The study also demonstrates the potential for these compounds to occupy chemical space inaccessible to aromatic systems, highlighting their utility in drug design. Mechanistic studies suggest an energy-transfer mechanism, with the excited state of the photocatalyst facilitating the cycloaddition. Later they presented a novel photocatalytic oxidative activation of bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes (BCBs) 98 using an acridinium organophotocatalyst, enabling formal [2σ + 2π] cycloadditions with alkenes and aldehydes 99 to form bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes and oxabicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 100. The reaction involves the formation of radical cation intermediates from BCBs, which then react with the alkenes or aldehydes. Mechanistic studies, including electrochemical, photophysical, radical trapping, and computational analyses, support the proposed oxidative pathways. The subtle interplay between the BCB and alkene identity dictates the reaction mechanism, leading to regiodivergent pathways and complementary products with up to >20:1 regioselectivity (Scheme 13C) [68]. This work highlights a rare example of oxidative BCB activation, expanding the synthetic utility of BCBs in organic synthesis.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 13. Ir-catalyzed photochemical intramolecular crossed [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of styrene derivatives. | |

In recent years, several elegant examples have been reported for bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes (BCBs) in radical cycloaddition reactions. Glorius group disclosed a strain-release-enabled ortho-selective [2π + 2σ] photocycloaddition of bicyclic aza-arenes 102 with bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes 101 (Scheme 14). In the presence of [Ir(dFCF3ppy)2(dtbbpy)](PF6) (2 mol%) as the photosensitizer under irradiation with blue LEDs (λmax = 450 nm) in CH2Cl2, this reaction strategy not only conserves the typical photolabile ortho-cycloaddition product but also provides access to highly decorated bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane frameworks in direct proximity to N-heteroarenes. The proposed mechanism is shown in Scheme 14. Photoexcited *IrⅢ oxidizes quinoline 105 in its excited state to form the respective radical cation 106. The selective addition of 101 to 106 yields cyclobutane radical cation 107. Alternatively, 107 can also be generated by oxidation of diradical 108, which is formed via the addition of 101 to 105. Cyclization of 107 subsequently forms radical cation 109. Finally, oxidation of neutral quinoline 104 by 109 propagates the radical chain by liberating the product 103 and regenerating 106 [69].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 14. Ir-catalyzed ortho-selective dearomative [2 + 2] photocycloadditions of bicyclic aza-arenes with bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. | |

In the same year, they also presented a visible-light-induced energy transfer strategy to synthesize polysubstituted 2-oxabicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 112 from benzoylformate esters 110 and bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes 111. The reaction involves a formal [2π + 2σ] photocycloaddition, followed by backbone C-H abstraction and aryl group migration (Scheme 15). The mechanism begins with energy transfer from the excited-state photocatalyst to the benzoylformate ester 110, generating an excited triplet state 113. This intermediate undergoes a stepwise radical process, including radical-radical coupling and aryl group migration, leading to the formation of the final product 112. The reaction is highly regioselective, driven by the formation of the most stable radical intermediate 114 [70].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 15. Ir-catalyzed [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of benzoylformate esters and bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. | |

Following this, Glorius's group reported an intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition enabled by triplet energy transfer, offering a simple, modular, and diastereoselective route to bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 117 from heterocyclic olefins 115, such as coumarins, flavones, and indoles (Scheme 16) [71]. This strategy, utilizing thioxanthone (TXT), extends intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloadditions to σ-bonds and accesses previously inaccessible structural motifs. The proposed stepwise mechanism through diradical intermediate 118 is outlined in Scheme 16.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 16. Intermolecular [2 + 2]-photocycloaddition enabled by triplet energy transfer. | |

In 2024, Glorius group reported the use of photoredox catalysis to generate bicyclo[1.1.0]butyl radical cations, which undergo highly regio- and diastereoselective [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions with a broad range of alkenes to afford bicyclohexanes 122 (Scheme 17A) [72]. The mechanism involves single-electron oxidation of bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes 119 to form radical cations, which then react with alkenes. DFT computations and experimental studies suggest that the initial interaction between the radical cation and the alkene leads to a radical addition, followed by intramolecular ring closure. In the same year, they described a photoredox-catalyzed method for the dearomative [2 + 2] cycloaddition of phenols 125 with bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes 124. This reaction produces bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane 126 units fused to cyclic enones (Scheme 17B) [73]. The mechanism likely involves the oxidation of either the phenol or the BCB by the excited photocatalyst, leading to a common intermediate 127 that undergoes cyclization. The study includes experimental evidence supporting the involvement of radical species. Following this, the same group presented a novel double strain-release [2π + 2σ] photocycloaddition reaction that synthesizes heterobicyclo[2.1.1]hexane units 129a, 129b using cyclobutenone 128 and bicyclo[1.1.0]butane (BCB) under visible light irradiation without a catalyst (Scheme 17C) [74]. The study demonstrates broad substrate scope, yielding diverse products with good functional group tolerance. Mechanistic studies, including UV-visible spectroscopy and DFT calculations, suggest a triplet state process involving a two-photon excitation of cyclobutenone to form a ketene intermediate, which then reacts with BCB. This work highlights a sustainable and efficient method for synthesis of complex sp3-rich molecules with potential applications in pharmaceuticals.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 17. Photosensitized [2 + 2] cycloadditions of bicyclobutanes. | |

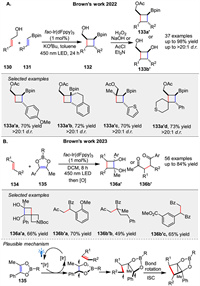

In 2022, the Brown group introduced a strategy for the photosensitized cycloaddition of alkenylboronates 131 and allylic alcohols 130 through temporary coordination. This approach allows for the synthesis of a diverse range of cyclobutylboronates 133a and cyclobutylalcohols 133b with high levels of stereo- and regiocontrol (Scheme 18A) [75]. The key to this method is the temporary coordination of the allylic alcohol 132 to the Bpin unit, which facilitates intramolecular cyclization. Following this, Brown group introduced another novel strategy for photosensitized [2 + 2] cycloadditions using dioxaboroles 135, leveraging boron ring constraint to enable efficient reactions with a broad range of alkenes 134. This method overcomes limitations of acyclic substrates by stabilizing dioxaborole intermediates, facilitating the synthesis of cyclobutyl diols 136a and 1,4-dicarbonyl compounds 136b. Demonstrated through the creation of valuable heterocycles and biatriosporin D, this approach offers high functional group tolerance and regioselectivity. Mechanistic studies suggest a photosensitization pathway involving triplet excited states and radical intermediates (Scheme 18B) [76].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 18. Ir-catalyzed [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions of alkenylboronates and dioxaboroles. | |

Photosensitized [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of N-sulfonylimines 137 was presented by Brown group in 2023, a method for the stereoselective construction of azetidine derivatives 139. Mechanistic studies suggested that the reactions proceed via Dexter energy transfer, where the excited triplet state of the photosensitizer transfers energy to the substrate, leading to the formation of a diradical intermediate that subsequently reacts to form the cycloaddition products (Scheme 19) [77].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 19. Ir-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of N-sulfonylimines with alkenes and alkynes. | |

A new strategy for synthesizing bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 142 via strain-release [2π + 2σ] cycloadditions initiated by energy transfer was presented by Brown group in 2022. The reaction involves sensitizing a BCB 140 with a sensitizer, such as 2,2’-OMeTX, followed by cycloaddition with an alkene 141. The mechanism of this strain-release [2π + 2σ] cycloaddition for synthesizing bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes involves energy transfer from a sensitizer to a naphthyl ketone-substituted BCB 140. Upon excitation, the BCB generates a triplet diradical intermediate through strain-release-induced bond cleavage. This intermediate reacts with an alkene 141, leading to the formation of the desired cyclobutanecarbaldehyde product 142 via intersystem crossing and bond formation. The process is facilitated by the use of a thioxanthone-based sensitizer, which enables selective energy transfer to the BCB, driving the reaction forward efficiently. This method allows for the synthesis of a diverse range of bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes with various substitution patterns (Scheme 20A) [78]. In 2023, the same group introduced the synthesis of 2-azanorbornanes 145 and 147 using strain-release formal cycloadditions initiated by energy transfer. They described two approaches: the formal cycloaddition of azahousanes with alkenes 144 and the formal cycloaddition of housanes with imines 146 [79]. The azahousane reagent was synthesized from Boc-Hyp-OMe through an Appel reaction and intramolecular nucleophilic substitution. The reaction with alkenes likely proceeds via Dexter energy transfer or direct excitation to 143, followed by intersystem crossing and homolysis of the strained C-C bond to generate a diradical intermediate 148, which then undergoes stepwise radical addition to form the product 145. Both methods are mild, scalable, and valuable for accessing new chemical spaces in the pharmaceutical industry (Scheme 20B).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 20. Visible light mediated cycloaddition of housane and azahousanes with alkenes and imines. | |

In the recent work, Brown group presented a novel strategy for photosensitized [2 + 2] cycloadditions between styrenyl dihaloboranes 149 and unactivated allylamines 150 (Scheme 21) [80]. The success of the reaction hinges on the use of dihaloboranes, which provide increased Lewis acidity necessary for amine coordination. Mechanistically, this [2 + 2] cycloaddition likely proceeds via energy transfer from the photosensitizer to the dihaloborane 149, followed by coordination and cycloaddition with the allylamine 150.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 21. Photosensitized [2 + 2] cycloadditions between styrenyl dihaloboranes and unactivated allylamines. | |

An enantioselective [2π + 2σ] photocycloaddition of BCBs 152 with vinylazaarenes 153, catalyzed by a chiral phosphoric acid 38b was described by Jiang group in 2024. This method yields high enantioselectivity and diastereoselectivity in producing bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane (BCH) derivatives 154 (Scheme 22A) [81].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 22. Enantoselective photosensitized [2 + 2] cycloadditions of BCBs. | |

Hong group also developed the photoinduced asymmetric cycloaddition of BCBs 155 and α,β-unsaturated ketones 156 using a chiral Brønsted acid catalyst 157. 156 is protonated by the catalyst and excited to a triplet state upon light irradiation 160. This triplet excited state undergoes a stepwise cycloaddition with the BCB (155), leading to the insertion of the α-carbon of the ketone into the BCB framework (161). The mechanism involves the formation of a diradical intermediate 162, which then cyclizes to form the desired chiral BCH product 158 (Scheme 22B) [82].

Very recently, Duan and Guo group presented a substrate-regulated divergent addition of N-sulfonyl ketimines 165 to BCBs 164 using photoinduced energy transfer resulting in benzosultam-fused aza-BCHs 166. The mechanism involves triplet energy transfer from a photosensitizer to the BCB 164, leading to cycloaddition with cyclic ketimines 165 (Scheme 23A) [83]. A highly regio- and enantioselective dearomative [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reaction between naphthalene derivatives 168 and BCBs 167 using Gd(Ⅲ) catalysis was presented by You and colleagues (Scheme 23B). This method, enabled by photoexcited Gd(Ⅲ) catalysis, allows for the synthesis of enantioenriched bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 170 with a variety of functional groups, achieving yields and enantioselectivities [84]. Mechanistic studies, including UV-vis absorption spectroscopy and triplet quenching experiments, suggest that the reaction involves the excitation of naphthalene to its triplet state 173, followed by radical addition to the BCB 167, leading to the formation of a 1,4-diradical intermediate 174 and subsequent product formation. The use of a chiral ligand 169 enhances substrate solubility and enantiocontrol through hydrogen bonding, facilitating efficient energy transfer. This work by You and colleagues represents a significant advancement in the field of photocatalysis and asymmetric synthesis.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 23. Visible-light photocatalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition of BCBs. | |

Very recently, Davies group presented a method for synthesizing highly functionalized bicyclo[2.1.0]pentanes (housanes) 179 through a two-step sequence involving a silver- or gold-catalyzed cyclopropenation of alkynes to form 177 followed by an intermolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reaction with electron-deficient alkenes 178. The cyclopropenation step utilizes aryldiazoacetates, while the [2 + 2] cycloaddition is achieved using blue LED irradiation and a commercially available photocatalyst as a triplet sensitizer at low temperatures (-40 ℃). The process is highly diastereoselective and proceeds with enantioretention when enantioenriched cyclopropenes are used (Scheme 24A) [85]. The method also allows for the generation of enantioenriched housanes and provides a streamlined approach to accessing complex, strained aliphatic rings with potential applications in medicinal chemistry. A [2 + 2] photocycloaddition of cyclopropenes bearing a styryl group 180 to create housane derivatives 181 was reported by Rubén’s group. The reaction is driven by selective excitation of the styrene fragment, leading to a stereoselective cycloaddition [86]. The mechanism involves generating an excited triplet state from the styrene fragment, which then undergoes a stepwise radical cycloaddition. The process is efficient and yields derivatives with high diastereoselectivity, using either an iridium complex or thioxanthone as a sensitizer (Scheme 24B).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 24. Ir-catalyzed intermolecular and intramolecular [2 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions to synthesize housanes. | |

2.2. [3 + 2] cycloaddition

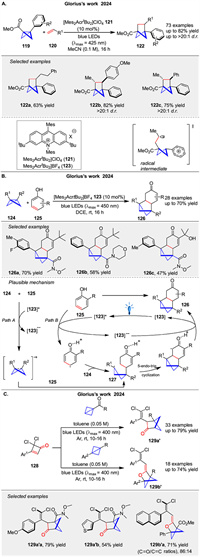

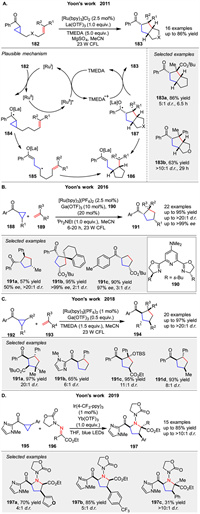

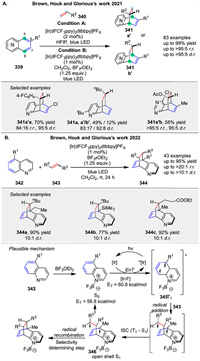

Highly substituted cyclopentane ring systems 183 were generated by the formal intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition of aryl cyclopropyl ketones with olefins 182 in 2011, as reported by Yoon and co-workers. This method utilized a photocatalytic system comprising a ruthenium photocatalyst [Ru(bpy)3]Cl2, the Lewis acid La(OTf)3, and TMEDA (Scheme 25A) [87]. The key initiation step involves the one-electron reduction of the ketone to the corresponding radical anion 184, which subsequently undergoes ring opening to generate the distonic radical anion 185. Sequential radical cyclizations then lead to the formation of the cyclized ketyl radical 183, promoting cycloaddition to form 187. The final product obtained through the loss of an electron, completing the formal intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition of 182. In 2016, the same group reported the enantioselective photocatalytic intermolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition of aryl cyclopropyl ketones 188 and alkenes 189. This method provides an asymmetric [3 + 2] photocycloaddition approach using ligand 190 to assemble structurally complex five-membered carbocycles 191, which are not synthetically accessible using other catalytic strategies (Scheme 25B) [88]. Two years later, the group further developed a general protocol for radical anion [3 + 2] cycloaddition under similar conditions to afford carbocycles 194 (Scheme 25C) [89]. This method offers a valuable complement to existing methodologies in the literature for constructing structurally complex five-membered-ring compounds. In 2019, building on their previous work, Yoon group attempted to replace the olefin reactant with hydrazones 196 and found that a range of structurally diverse pyrrolidine rings 197 could be synthesized using their previously reported photoredox catalysis strategy (Scheme 25D) [90]. The key insight that enabled the expansion of the scope of photoredox [3 + 2] cycloadditions to C=N electrophiles was the use of a redox auxiliary strategy. This approach allowed for the photoreductive activation of the cyclopropyl ketone 195 without the need for an exogenous tertiary amine co-reductant.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 25. Ru/Ir-catalyzed [3 + 2] photocycloaddition of aryl cyclopropyl ketones with olefins. | |

Another [3 + 2] photocatalytic cycloaddition of phenols 198 and alkene 199, for synthesizing dihydrobenzofuran products 200 developed by Yoon group in 2014. This protocol utilized visible-light-activated transition metal photocatalysis, specifically employing ammonium persulfate as a benign terminal oxidant. This method enables the modular synthesis of a broad range of dihydrobenzofuran products 200 with high yields and selectivity. The study highlights the potential of photoredox catalysis for oxidative transformations, offering a practical and environmentally friendly alternative to traditional synthetic methods. The mechanism of this oxidative [3 + 2] cycloaddition of phenols and alkenes involves a slow salt metathesis process where Ru(bpz)32+ forms an insoluble Ru(bpz)3(S2O8) complex. Upon photoexcitation, this complex generates the active oxidant Ru(bpz)33+ and a sulfate radical anion. The phenol is oxidized to form a phenoxonium cation 201, which is then trapped by an electron-rich alkene 199 to form the desired dihydrobenzofuran product 200. This photocatalytic process requires both light and the Ru(bpz)32+ catalyst, highlighting the importance of these components in driving the reaction forward. The applicability of this photocatalytic method was also demonstrated by the ability to synthesize the large family of bioactive benzofuranoid natural products (Scheme 26) [91].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 26. Ru-catalyzed [3 + 2] photocycloaddition of phenols and alkenes. | |

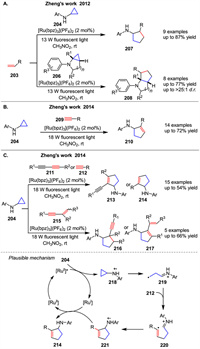

In 2012 and 2014, Zheng group reported intermolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of monocyclic cyclopropylanilines 204 with alkenes 203 [92], alkynes 209 [93], diynes 211, and enynes 212 [94] via visible light photoredox catalysis, yielding a variety of methods exhibit significant functional group tolerance, particularly with heterocycles such as fused indolines. Mechanistically, the annulation likely proceeds through the cyclic allylic amine radical cation 221. Using [Ru(bpz)3](PF6)2 as an effective photocatalyst, this pathway shown in Schemes 27A-C. The photoexcited Ru(bpz)32+ oxidizes 204 to the corresponding amine radical cation 218, which triggers cyclopropyl ring opening to generate distonic radical cation 219. The primary carbon radical of 219 adds to the alkynes 212 to afford vinyl radical 220. Intramolecular addition of the vinyl radical to the iminium ion of distonic radical cation closes the five-membered ring, furnishing amine radical cation 221. Finally, Ru(bpz)3+ reduces 221 to the annulation product 214 while regenerating Ru(bpz)32+. In 2017, the same group presented the detection of transient amine radical cations involved in the reaction of 204 and styrene using electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) in combination with online laser irradiation of the reaction mixture [95]. In particular, the reactive radical cation 218, the reduced photocatalyst RuⅠ(bpz)3+, and the product radical cation 221 were all successfully detected and confirmed by high-resolution MS. Thus, this strategy provides a powerful analytical tool to detect transient intermediates and study visible-light photocatalysis mechanistically.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 27. Ru-catalyzed [3 + 2] photocycloaddition of cyclopropylanilines with alkenes, alkynes, enynes, and diynes. | |

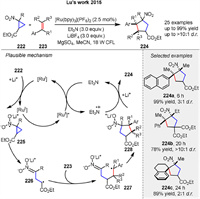

The first nitro-group-initiated redox-neutral [3 + 2] cycloaddition of nitrocyclopropanes 222 with alkenes 223, using photocatalyst [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2, was reported by Lu group in 2015. Photoexcitation of Ru(bpy)32+ with visible light results in a photoexcited state *Ru(bpy)32+, which can undergo reductive quenching by Et3N to generate the Ru(bpy)3+ species. This powerful reducing agent can transfer an electron to 222. The distonic radical anion 226, generated from the nitrocyclopropane radical anion 225, can be trapped by styrenes 223 and then undergo intramolecular radical cyclization of 227, followed by the loss of one electron from 228 to afford the products 224 (Scheme 28) [96]. Various functional groups can be tolerated, and multiple quaternary carbon centers are formed with high diastereoselectivity under these reaction conditions.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 28. [3 + 2] redox-neutral cycloaddition of nitrocyclopropanes with styrenes by visible-light photocatalysis. | |

In 2018, Meggers and co-workers reported a conceptually straightforward and effective protocol for the asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition between cyclopropanes 229 and a wide range of alkenes or alkynes 230 by employing a single Rh-based chiral Lewis acid catalyst. This protocol provides access to chiral cyclopentanes and cyclopentenes 231 in up to 99% yields and with excellent enantioselectivities of up to >99% ee (Scheme 29) [97]. The proposed mechanism involves the generation of complex 232 upon bidentate coordination of the cyclopropane substrate 229 to the rhodium complex 46. After photoexcitation, intermediate 233 serves as a strong oxidant and is reduced by a tertiary amine to form intermediate 234, which subsequently ring-opens to generate the radical intermediate 235. The subsequent radical addition with 230 affords the corresponding ketyl radical intermediate 236. Finally, ligand exchange regenerates the catalyst/substrate complex 232, completing the catalytic cycle and releasing the cycloaddition product 231.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 29. Rh-catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] photocycloadditions of cyclopropanes with alkenes or alkynes. | |

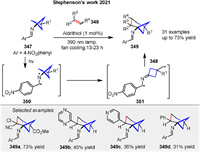

In 2019, Stephenson group described the photochemical conversion of aminocyclopropanes 237 into 1-aminonorbornanes 238 via formal [3 + 2] cycloadditions initiated by homolytic fragmentation of amine radical cation intermediates [98]. Mechanistically, the oxidation of 237 generates amine radical cations that undergo β-scission to form β-iminium radicals 240. This enables a 6-exo-trig radical cyclization to produce distonic radical cations 241, followed by a 5-exo-trig cyclization to forge the norbornane core 242. Reduction to the product 238 closes the catalytic cycle (or propagates the chain), providing a net redox-neutral transformation (Scheme 30A). In 2019, Stephenson group reported the development of an intramolecular masked N-centered radical strategy that harnesses the energy of light to drive the conversion of cyclopropylimines 243 to 1-aminonorbornanes 244 (Scheme 30B) [99]. The proposed mechanism involves an N-centered radical 245 initiating the strain-driven homolysis of the cyclopropane ring, generating a formal β-iminyl radical intermediate 246. Intermediate 246 then engages in an intramolecular addition to the alkene, followed by an intramolecular 5-exo-trig cyclization, resulting in the formation of cycloheptane 247. Notably, both radicals of the excited state imine are terminated via recombination to regenerate the C-N bond, yielding the desired 1-aminonorbornanes 244. In a similar vein, they detailed the development of a photochemical intermolecular formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition between cyclopropylimines 248 and substituted alkenes 249 to generate aminocyclopentane derivatives 250 in 2022 (Scheme 30C) [100]. These new photochemical transformations thus provide new avenues for the modern synthetic photochemist.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 30. Intra- and intermolecular [3 + 2] photocycloadditions of cyclopropanes with alkenes. | |

After that, Stephenson group presented a photochemical method for synthesizing 2-azanorbornane 253 scaffolds from cyclopropylsulfonamide derivatives 251. The method employs a Lewis acid additive to promote the formation of amine radical cations, initiating a cascade radical cyclization sequence. This approach allows for the synthesis of substituted 2-azanorbornanes at all possible carbon centers. A plausible catalytic cycle is illustrated in Scheme 31A [101]. The mild and modular nature of this method makes it a valuable tool for accessing saturated aza-heterocycles, which are of significant interest in medicinal chemistry due to their potential as bioactive molecules. Another [3 + 2] photochemical method was presented by Stephensen’s group in 2024. For synthesizing bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes using imine photochemistry, this approach involves an intramolecular formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition of allylated cyclopropanes with a 4-nitrobenzimine substituent 258, allowing for high functional group tolerance and mild reaction conditions via diradical intermediate. The resulting imines 259 can be hydrolyzed to yield primary amine building blocks, demonstrating the versatility of this method in preparing complex bicyclic scaffolds (Scheme 31B) [102].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 31. Intramolecular [3 + 2] photocycloadditions of cyclopropanes with alkenes. | |

In 2020, Ooi group strategically utilized urea as a redox-active directing group with anion-binding ability to achieve photoinduced, highly diastereo- and enantioselective [3 + 2] cycloaddition of cyclopropylamine 260 with α-alkylstyrenes 261, providing access to a series of aminocyclopentanes 264 bearing stereochemically defined, vicinal tertiary and quaternary stereocenters [103]. A preparatory step involves the assembly of the photoactive Ir-chiral borate ion pair 262 and the 260 into the supramolecular ion pair 265. Upon irradiation with visible light, 265 is excited and undergoes single-electron transfer (SET) to generate intermediate 266. In this assembly, the radical cation 267 is considered to exist as a formal equilibrium mixture of an N-radical cation and a distonic radical cation, with the latter reacting with the alkene 261. The intermediary alkyl radical 268 then undergoes stereoselective five-exo cyclization under the guidance of the accompanying 262 to afford aminocyclopentane 270 in the form of an N-radical cation paired with 262 (Scheme 32).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 32. Iridium-chiral borate ion pairs induced [3 + 2] cycloaddition of N-cyclopropylurea with α-alkylstyrenes. | |

A radical-based asymmetric olefin difunctionalization strategy for rapidly forging all-carbon quaternary stereocenters to diverse azaarenes 273 was presented by Jiang group in 2020 (Scheme 33A) [104]. Under cooperative photoredox and Brønsted acid catalysis, readily accessible cyclopropylamines 204 and α-branched 2-vinylazaarenes 271 can efficiently undergo a tandem two-step radical addition process, accomplishing a formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition. In 2022, the same group developed redox-neutral, asymmetric [3 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions of N-aryl cyclopropylanilines 204 with a variety of electron-rich and electron-neutral olefins 271 via cooperative visible-light-driven photoredox and chiral H-bond catalysis (Scheme 33B) [105]. Mechanistically, catalyst 38b and 204 might form a noncovalent complex with a H-bonding interaction between the N-H of 204 and the P=O of 38b. After photoexcitation, DPZ* serves as an oxidant and is reduced by the amine moiety of 204, and then the resulting radical cation 276 undergoes ring-opening to form intermediate 277. With the help of another H-bonding interaction between the OTf of alkene 274 and the P-OH group of 38b, the subsequent intermolecular radical addition proceeds and leads to radical intermediate 278. Given the formation of stereogenic centers, the subsequent cyclization via radical addition to generate radical cation 279 is responsible for determining enantio- and diastereose-lectivities. Finally, the oxidizing amine radical cation 279 accepts an electron from DPZ•- to give product 275.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 33. Photoredox and bronsted acid or chiral H-bond catalyst co-catalyzed [3 + 2] photocycloadditions. | |

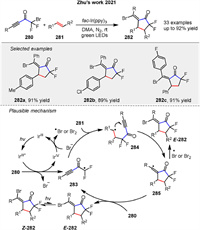

In 2021, Zhu group developed a radical-mediated [3 + 2] cycloaddition to synthesize α,α-difluorocyclopentanones 282 using bromodifluoromethyl alkynyl ketones 280 and alkenes 281 under photochemical conditions with DMA as solvent and fac-Ir(ppy)3 as photosensitizer under green LED irradiation. The reaction showed broad functional group tolerance yielding products with good selectivity and allowing further transformations through cross-coupling reactions (Scheme 34) [106]. The mechanism involves SET from the excited photosensitizer to the ketone 280, forming a difluoromethyl radical 283 that adds to the alkene 281 and undergoes intramolecular cyclization, intercepted by bromine to form the product 282.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 34. Visible-light-mediated radical [3 + 2] cycloaddition for synthesis of difluorocyclopentanones. | |

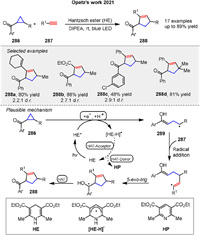

In 2021, Opatz group presented a metal-free, Hantzsch ester-mediated synthesis of cyclopentenylketones 288 from ketocyclopropanes 286 under eco-friendly conditions (Scheme 35). They explore the mechanism of these transformations, focusing on the role of the Hantzsch ester in facilitating the reactions. The mechanism involves the initial photoexcitation of the Hantzsch ester, which generates a highly reducing species capable of inducing SET to the carbonyl group of the cyclopropane 286. This SET step leads to the formation of a ketyl radical intermediate, which undergoes ring-opening to produce a radical species 289. This radical then reacts with terminal alkynes 287 through a radical addition and cyclization pathway, resulting in the formation of cyclopentenes 288. This work provides a sustainable and efficient method for the synthesis of complex cyclopentene structures, leveraging the strain release from cyclopropane intermediates [107].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 35. Visible-light mediated metal-free [3 + 2] cycloaddition of ketocyclopropanes and terminal alkynes. | |

In 2022, Molander group disclosed the first photoinduced [3σ + 2σ] cycloaddition for the synthesis of trisubstituted bicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes 291 using bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes 290 and cyclopropylamines 204 (Scheme 36) [108]. SET to the cyclopropylamine 204 induces the formation of the radical cation species 292, followed by ring opening via β-scission to the distonic radical cation 293. Subsequent addition of 290 furnishes another relatively stabilized distonic radical cation 294. The specie 294 then undergoes cyclization, providing access to the radical cation 295, which can be reduced by the IrⅡ species generated in the reductive quenching photoredox cycle or by the presence of the cyclopropylamine 204.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 36. Ir-catalyzed photochemical intermolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. | |

In 2022, Aleman group introduced a visible-light-mediated strategy for the asymmetric synthesis of cyclic β-amino carbonyl derivatives 297 bearing three contiguous stereogenic centers through a formal [3 + 2] photocycloaddition (Scheme 37) [109]. The reaction involves the use of a chiral-at-rhodium catalyst to promote the enantioselective [3 + 2] photocycloaddition between α,β-unsaturated acyl imidazoles 296 and cyclopropylamine 204 derivatives. Mechanically, the authors proposed that it can evolve in two different pathways, in which the one involved in radical cycloaddition strategy is shown in Scheme 37. The mechanism begins with the coordination of the acyl imidazole 296 to the rhodium complex 46, forming an intermediate that, upon blue LED irradiation, reaches an excited state 298 capable of oxidizing the cyclopropylamine 204. This generates a radical cation of the amine 301, which reacts with the rhodium complex 302 to form the final cyclopentane product 297. The study achieves excellent enantioselectivity (up to 95% ee) and demonstrates the utility of the method through various synthetic transformations.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 37. Asymmetric synthesis of cyclic β-amino carbonyl derivatives by a formal [3 + 2] photocycloaddition. | |

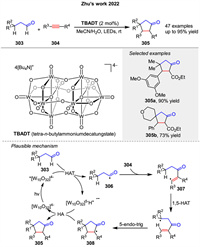

In the same year, a novel method for synthesizing cyclopentanones 305 through a photoinduced [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of alkyl aldehydes 303 and alkynes 304 enabled by photoinduced hydrogen atom transfer was presented by Zhu group (Scheme 38). First, the decatungstate anion (TBADT) is photoexcited to form an excited state, which abstracts a hydrogen atom from an aldehyde 303, generating an acyl radical 306. This radical then adds to an alkyne 304 to form a vinyl radical 37, which undergoes 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) and a rare 5-endo-trig cyclization to form a cyclopentanone 308 intermediate. Finally, a back-hydrogen abstraction by the reduced form of the tungstate anion restores the catalyst and completes the cycle. This process is highly selective and atom-economic, producing complex cyclopentanone 305 with excellent site-, regio-, and diastereoselectivity under mild conditions [110].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 38. Photoinduced decatungstate-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition of various internal alkynes with aliphatic aldehydes. | |

In 2022, Glorius group described a visible-light photocatalyzed peri-[3 + 2] cycloaddition of quinolines 309 with alkynes 310 to synthesize aza-acenaphthenes 311. The reaction uses an iridium complex as both a photosensitizer and a photoredox catalyst, driving a cyclization/rearomatization cascade. Initially, energy transfer from the excited photocatalyst to the quinoline generates a triplet state, which reacts with the alkyne to form a cycloadduct. Subsequent redox shuttling, involving reductive quenching and oxidation steps, leads to aromatization of the product [111]. The process is highly regio- and diastereoselective, yielding products with excellent selectivity. Density functional theory calculations support the intertwined energy transfer/single electron transfer nature of the mechanism, highlighting the role of electron-withdrawing groups in facilitating the rearomatization step. Later, Hong group reported a novel approach to synthesize ortho-pyridyl γ- and δ-lactam scaffolds 313 through a photoinduced [3 + 2] cycloaddition reaction. The key innovation in this energy-transfer-induced [3 + 2] cycloaddition of N-N pyridinium ylides 312 lies in their unique triplet-state reactivity when activated by a photosensitizer under visible light. The reaction mechanism involves initial EnT from the excited photosensitizer to the N-N pyridinium ylide 312, generating a triplet diradical intermediate 314. This intermediate then undergoes radical addition to the alkene, followed by cyclization to form the desired lactam product 313 with high diastereoselectivity (Scheme 39) [112].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 39. Energy-transfer-induced [3 + 2] cycloadditions of N-N pyridinium ylide synthesis of cyclopentanones. | |

In 2023 Waser’s group presented a photocatalytic method for the homolytic ring-opening of carbonyl cyclopropanes 315 to synthesize 5-membered carbocycles 317 and BCHs 318. The study optimizes conditions using thioxanthone and iridium-based photocatalysts, achieving good yields with various substrates [113]. Mechanistic studies suggest a 1,3-biradical intermediate is key to the transformation (Scheme 40A). Recetly, Glorius group presented an energy transfer (EnT)-catalyzed method to generate strained 2H-azirines from isoxazole-5(4H)-ones 319, which then undergo a formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition with various electrophiles [114]. The process involves triplet energy transfer to form a reactive azaallenyl diradical intermediate, leading to cycloaddition products with high selectivity. This mild method enables the rapid synthesis of valuable cyclic imines 320 and their derivatives (Scheme 40B).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 40. Ir-catalyzed intermolecular and intramolecular [3 + 2] photocycloaddition reactions. | |

2.3. [4 + 2] cycloaddition

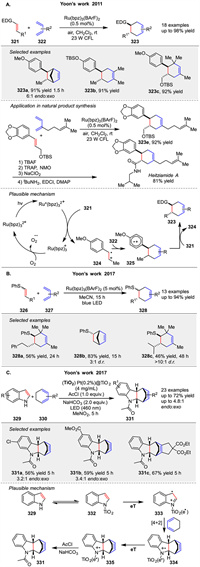

A visible light photocatalysis method for radical cation Diels Alder cycloadditions using rutheniumⅡ polypyridyl complexes was developed by Yoon group in 2011. The reaction efficiently forms [4 + 2] cycloadducts between electron-rich dienophiles 321 and dienes 322 under mild conditions. The mechanism involves photoexcitation of the ruthenium complex, followed by oxidative quenching to generate the radical cation intermediate 324, which then reacts with the diene 322. This method is highly efficient, yielding high products with short reaction times. They also applied this method for synthesis of natural product heitziamide A (Scheme 41A) [115]. In 2017, they introduced a redox auxiliary strategy for radical cation cycloadditions using arylsulfide moieties 326. This approach enables the photocatalytic generation of alkene radical cations that undergo cycloadditions with electron-rich partners. The sulfide auxiliary is later cleaved to obtain the desired products. The mechanism involves photooxidation of the vinyl sulfide to form the radical cation, which then reacts with the diene or alkene (Scheme 41B) [116]. This method overcomes the limitations of direct photoredox activation of simple alkenes. In the same year, they described a heterogeneous photocatalytic Diels Alder reaction of indoles 329 using Pt(0.2%)@TiO2 under visible light. The reaction involves the formation of indole radical cations 333 that react with electron-rich dienes 330. The mechanism includes indole adsorption on TiO2, visible light excitation, and radical cation formation, followed by cycloaddition and reduction by the catalyst (Scheme 41C) [117]. The reaction is efficient, with broad scope and good catalyst recyclability, offering advantages over homogeneous methods.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 41. Ru and Pt catalyzed [4 + 2] photocycloadditions of diene and dienophile. | |

In 2015, Zheng group reported the first example of an intermolecular [4 + 2] annulation of cyclobutylanilines 336 with alkynes 337 enabled by visible-light photocatalysis (Scheme 42) [118]. After extensive screening, [Ir(dtbbpy)(ppy)2](PF6) in MeOH under irradiation with two 18 W LEDs was identified as the optimal condition, providing the desired product in 97% yield as determined by gas chromatography. Monocyclic and bicyclic cyclobutylanilines successfully undergo the annulation with terminal and internal alkynes to generate a wide variety of amine-substituted cyclohexenes 338. This approach can potentially be applied to open rings larger than three- and four-membered rings, provided they have suitable built-in ring strain. The plausible catalytic mechanism of this reaction is similar to Scheme 27.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 42. Ir-catalyzed [4 + 2] cycloaddition of cyclobutylaniline with alkyne. | |

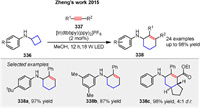

Photochemical intermolecular dearomative cycloaddition of azaarenes 339 with alkenes 340, enabled by energy transfer (EnT) and Lewis acid mediation was reported by Brown group in 2021. This method allows for the selective formation of para-cycloadducts 341 with high diastereo- and regioselectivity. (Scheme 43A) [119]. In 2022, following the same mechanism, another photochemical intermolecular dearomative cycloaddition of quinolines 342 with alkenes 343, enabled by energy transfer (EnT) and Lewis acid mediation was reported by their group (Scheme 43B) [120]. The reaction involves the formation of a triplet state intermediate 345 through EnT from a photosensitizer to the azaarene 342, followed by a stepwise radical addition to the alkene 343. The mechanism includes a reversible radical addition and a selectivity-determining radical recombination. The study also revealed that the stability of the biradical intermediate 346 and the solvent polarity significantly influence the regioselectivity and diastereoselectivity of the reaction. The reaction was shown to be applicable to a wide range of substrates, including sterically congested alkenes and allenes.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 43. Visible-light-mediated dearomative [4 + 2] cycloaddition of azaarenes with alkenes. | |

The conversion of bicyclo[1.1.1]pentan-1-amines 347 to a wide range of polysubstituted bicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-1-amines 349 was reported by Stephenson group in 2021 through a photochemical formal [4 + 2] cycloaddition of an intermediate imine diradical 351. The mechanism involves the generation of an excited state imine diradical intermediate 350 upon irradiation with visible light. This excited state facilitates the homolytic cleavage of a bond in the adjacent cyclopropane ring, leading to the formation of a reactive diradical intermediate 351. This diradical 351 can then add to an alkene 348, followed by a cyclization step to form the desired bicyclo[3.1.1]heptan-1-amine product 349. The process is photochemical in nature, requiring light activation to proceed, and results in the conversion of a bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane skeleton 347 to a more complex bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane skeleton 349, providing a rich source of sp3-rich primary amine building blocks for medicinal chemistry. This represents the first reported method to convert the bicyclo[1.1.1]pentane skeleton 347 to the bicyclo[3.1.1]heptane skeleton 349 (Scheme 44) [121].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 44. N-Centered radical induced photocycloadditions of imine-substituted bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes and alkenes. | |

Recently, Wang group developed a visible-light-promoted [4 + 2] cycloaddition of arylcyclobutylamines 352 with olefins 353 using QXPT-NPhCN as an organic photoredox catalyst (Scheme 45) [122]. First, the single-electron oxidation of 352 is accompanied by the deprotonation under the action of K3PO₄ and photoexcited [QXPT-NPhCN]*, generating the nitrogen radical intermediate 355 and the radical anion [QXPT-NPhCN]•−. The ring tension leads to the ring-opening of cyclobutane to form the alkyl radical 356. Intermolecular addition of the carbon radical in 356 to the olefins 353 affords 357. Intramolecular addition of the newly generated carbon radical to the iminium affords the nitrogen radical intermediate 358. The free radical anion QXPT-NPhCN•− performs single-electron reduction of 358, which is accompanied by protonation to give 354 and the ground state QXPT-NPhCN is regenerated to complete the catalytic cycle.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 45. Visible-light organophotoredox-mediated intermolecular formal [4 + 2] cycloadditions of arylcyclobutylamines with olefins. | |

Photosensitized [4 + 2] cycloaddition reactions of N-sulfonylimines 359 was presented by Brown’s group in 2023, a method for the stereoselective construction of 3D bicyclic scaffolds 361. This [4 + 2] cycloaddition involves the use of a rigid sulfonyl imine 359, which provides high diastereoselectivity and yield when reacted with various alkenylarenes 360. Mechanistic studies suggested that the reactions proceed via Dexter energy transfer, where the excited triplet state of the photosensitizer transfers energy to the substrate, leading to the formation of a diradical intermediate 362 that subsequently reacts with alkene 360 to form the cycloaddition products 361 (Scheme 46) [77].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 46. Ir-catalyzed [4 + 2] photocycloadditions of imine-substituted bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes and alkenes. | |

Fang and Guo group recently introduced a novel method for synthesizing pyrido[1,2-a]indol-6(7H)-ones 364 via a visible light-photocatalyzed formal [4 + 2] cycloaddition reaction involving indole-derived bromides 363 and alkenes or alkynes [123]. The reaction mechanism commences with the photoexcitation of the organic photocatalyst (PC-B) under visible light, generating an excited state with sufficient reducing power to induce the formation of a free radical 365 from the indole-derived bromide 363. This radical subsequently reacts with the alkene or alkyne substrate to form a second radical intermediate 366, which then undergoes radical cyclization by attacking the 2-position of the indole ring to yield the final product 364. Control experiments confirmed that both the photocatalyst and visible light are essential for the reaction, and the addition of a radical scavenger significantly inhibits the reaction, thereby validating its radical nature (Scheme 47).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 47. Visible-light photocatalyzed formal [4 + 2] cycloaddition of indole-derived bromides and alkenes or alkynes. | |

Shortly, Brown group presented a novel strategy for photosensitized dearomative [4 + 2] cycloaddition of naphthalenes 368 using a boron-enabled temporary tethering strategy (Scheme 48) [80]. The success of the reaction hinges on the use of dihaloboranes 367, which provide increased Lewis acidity necessary for amine coordination. This dienophile [4 + 2] cycloaddition yields complex 3D borylated bicyclic motifs 369 with high selectivity through energy transfer to the naphthalene 368, followed by stepwise radical cycloaddition.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 48. Dearomative [4 + 2] photocycloaddition of naphthalenes using a boron-enabled temporary tethering strategy. | |

3. Transition metal catalyzed RCRs 3.1. [2 + 2] cycloaddition

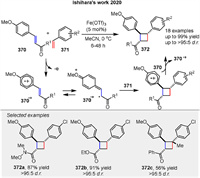

A radical-cation-induced crossed [2 + 2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient anetholes initiated by IronⅢ salt, described by Ishihara and coworkers. The use of Fe(OTf)3 to initiate the crossed [2 + 2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient anetholes 370 with styrenes 371, producing 1,2-diarylcyclobutanes 372. The mechanism involves the formation of a radical cation intermediate from the anethole (370.+), which reacts with styrene to form the cyclobutane product. This study highlights the utility of radical intermediates in constructing complex cyclic structures with broad substrate scopes and high yields (Scheme 49) [124].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 49. Fe-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition of electron-deficient anetholes. | |

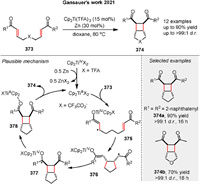

In 2021, Gansauer and co-workers reported a titanocene-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition reaction of bisenones 373 (Scheme 50) [125]. Both experimental evidence and theoretical results support the proposed radical pathway. The reaction begins with an inner-sphere electron transfer to the enone complexed to TiⅢ, generating the stabilized radical 375, which constitutes the oxidative addition step. This is followed by a 5-exo cyclization of the stabilized radical anion 375 to yield intermediate 376. Radical 377 is then formed by a 4-exo cyclization of the enoyl radical in 376 to the titanocene enolate. Finally, product 374 is released, and the catalyst is regenerated by back electron transfer from the ketyl radical to TiⅣ and dissociation of 378*Cp2TiⅢTFA.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 50. Ti-catalyzed [2 + 2] cycloaddition of bisenones. | |

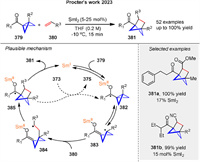

Recently, Procter and coworkers disclosed a broadly applicable catalytic approach that delivers substituted bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes 381 by intermolecular coupling between olefins 380 and bicyclo[1.1.0]butyl ketones 379. The product bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane ketones have been shown to be versatile synthetic intermediates through selective downstream manipulation. The proposed mechanism involves reversible SET from SmI2 to ketones 380, generating ketyl radicals 382, which fragment to give enolate radicals 383. Intermolecular coupling with electron-deficient alkenes 380 generates radicals 384, which rebound by addition to the SmⅢ-enolate moiety, generating new ketyl radicals 385. Back electron transfer to SmⅢ regenerates the SmI2 catalyst and liberates product 381 (Scheme 51) [126]. It is also possible that ketyl radical 385 directly reduces the starting ketone 379, although computational calculations favor a radical relay process.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 51. SmI2-catalyzed insertion of electron-deficient alkenes into bicyclo[1.1.0]butyl ketones. | |

3.2. [3 + 2] cycloaddition

Since William A. Nugen's pioneering work in 1988 on TiⅢ-induced cyclization of epoxyolefins [127], TiⅢ-based reductive SET reagents have become widely used for mediating cyclizations. In 2012, Robert A. Flowers Ⅱ's group introduced a novel approach to catalytic reactions employing oxidative additions and reductive eliminations in single-electron steps [128]. The success of radical aromatic substitution relies critically on a mechanism-based approach for tuning the stability and electronic properties of the catalyst.

In 2017, Lin and co-workers reported a Ti-catalyzed radical formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition of N-acylaziridines 386 with alkenes 387 The process begins with the coordination of the Ti catalyst to 376, inducing homolytic cleavage of the C-N bond and subsequent SET from the metal center to the substrate. This generates the radical intermediate 389, which adds to alkene 387 to form radical adduct. Cyclization of this adduct yields the final product 388, completing the cycloaddition. Meanwhile, the metal complex is reduced and released from the pyrrolidine product, regenerating the active catalyst (Scheme 52A) [129]. Shortly thereafter, employing the same radical redox relay strategy, the same group reported a diastereo- and enantioselective formal [3 + 2] cycloaddition of cyclopropyl ketones 390 with alkenes 391 [130]. Utilizing 392 as the Ti catalyst, a wide range of alkenes were found to be excellent coupling partners, affording the corresponding products with high diastereoselectivity (d.r.) and enantioselectivity (ee). In 2020, the group conducted mechanistic studies of this asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition [131]. The reaction commences with the generation of an active TiⅢ catalyst through single-electron reduction by Mn. Subsequently, the cyclopropyl substrate 390 undergoes regioselective reductive ring opening by the TiⅢ catalyst, yielding a tertiary carbon-centered radical 390a. This radical adds to alkene 391 to form intermediate 394, which then cyclizes to produce the final product 393 (Scheme 52B).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 52. Ti-catalyzed radical formal [3 + 2] cycloadditions of N-acylaziridines and cyclopropyl ketones with alkenes. | |

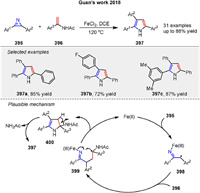

A Fe-catalyzed radical cycloaddition of 2H-azirines 395 and enamides 396 for the synthesis of substituted pyrroles 397 has been developed by Guan’s group in 2018 (Scheme 53) [132]. The reaction uses readily available starting materials, tolerates various functional groups, and proceeds through a conceptually new homolytic C-N bond cleavage and radical coupling with enamides under mild conditions, allowing the rapid synthesis of valuable triaryl-substituted pyrroles in high yields. A tentative mechanism is proposed in Scheme 53. First, the reductive radical ring-opening of 2H-azirine 395 occurs in the presence of FeⅡ to give a secondary radical intermediate 398. Next, radical coupling of intermediate 398 with enamide 396 affords the tertiary radical intermediate 399. Then, oxidative radical ring closure of intermediate 399 gives intermediate 400. Simultaneously, the active FeⅡ catalyst is released to facilitate the next catalytic cycle. Finally, elimination of a molecule of amide (NH2Ac), followed by tautomerization, produces the pyrrole 397.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 53. Fe-catalyzed radical cycloaddition of 2H-azirines and enamides. | |

In 2018, Wang and co-workers detailed the development of [3 + 2] cycloaddition reactions catalyzed by dirhodium(Ⅱ) complexes 402 between N-arylaminocyclopropanes 204 and alkene derivatives 401 [133]. Soon after, they reported a similar reaction between N-arylaminocyclopropanes 204 and alkyne derivatives 404, which broadens the scope of this method to include alkynyl groups (Scheme 54) [134]. Preliminary mechanistic studies suggest that dirhodium(Ⅱ) complexes 402 may facilitate the formation of N-centered radicals 407 by the loss of a hydrogen atom. This is followed by cyclopropane ring-opening to generate radical 408, which is trapped by alkene 401 to form intermediate 409. Subsequently, intramolecular free radical addition occurs to yield 410. After HAT from complex 406, the desired product 403 is obtained, and the N-centered radical 407 is regenerated.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 54. Rh(ll)-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the N-arylaminocyclopropane with alkene and alkyne derivatives. | |

Since its first use 40 years ago, SmI2 (Kagan's reagent) has remained one of the most versatile and selective SET reagents. Procter and co-workers have extensively explored the use of SmI2 to catalyze various intramolecular and intermolecular cycloaddition reactions, making significant contributions to the field. In 2019, they reported an intramolecular radical cyclization cascade catalyzed by SmI2 (Scheme 55A) [135]. Using as little as 5 mol% SmI2, they achieved the synthesis of complex three-dimensional polycyclic products 412 containing up to four stereocenters, typically with high yields and good diastereocontrol. Mechanistic studies support a radical relay mechanism. The key step involves the formation of ketyl radical 413 via reversible SET from SmI2 to substrate 411. Ketyl radical 413 fragments to form distal radical 414, which then cyclizes to generate radical 415. This radical rebounds by adding to the SmⅢ-enolate moiety, forming new ketyl radical 416. Back electron transfer to SmⅢ regenerates the SmI2 catalyst and releases product 412. In the same year, they also reported a similar SmI2-catalyzed radical cascade cyclization of 417 that constructs quaternary stereocenters 418 (Scheme 55B) [136], with a reaction mechanism consistent with their previously proposed catalytic cycle.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 55. Sml2-catalyzed intramolecular [3 + 2] cycloaddition by radical relay. | |

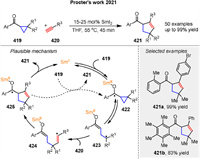

In 2021, based on their previous work, they described a SmI2-catalyzed intermolecular radical coupling of aryl cyclopropyl ketones 419 and alkynes 420 [137]. The process shows a broad substrate scope and delivers a library of decorated cyclopentenes 421 with SmI2 loadings as low as 15 mol% (Scheme 56). The proposed mechanism involves reversible SET from SmI2 to ketone 419, generating ketyl radical 422, which fragments to give enolate/radical 423. Intermolecular coupling with alkynes 420 generates radical 424, which rebounds by addition to the SmⅢ-enolate moiety, generating new ketyl radical 425. Back electron transfer to SmⅢ regenerates the SmI2 catalyst and liberates product 421. It is also possible that ketyl radical 425 directly reduces the starting ketone 419, feeding an electron-transfer-chain mechanism.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 56. Sml2-catalyzed intermolecular radical coupling of aryl cyclopropyl ketones and alkynes. | |

In 2024, Procter's group reported an approach to catalytic formal [3 + 2] cycloadditions using alkyl cyclopropyl ketones 426 as substrates, including more complex bicyclic alkyl cyclopropyl ketone 429. This method efficiently delivers complex, sp3-rich products 428 and 431 through cycloadditions with alkenes, alkynes, and enynes (Scheme 57) [138]. The key to engaging these relatively unreactive substrates lies in using SmI2 as a catalyst, combined with sub stoichiometric amounts of Sm⁰ to prevent catalyst deactivation. The mechanism involves a SET from SmI2 to the carbonyl group, generating a ketyl radical intermediate that undergoes ring-opening and subsequent coupling with the alkene or alkyne partner. Computational studies reveal that reactivity is influenced by both electronic and steric factors, with bicyclic substrates showing lower activation barriers. This work expands the scope of substrates for catalytic [3 + 2] cycloadditions and offers practical approaches for SmI2 catalysis.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 57. SmI2-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition of alkyl cyclopropyl ketones. | |

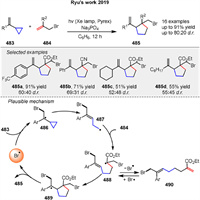

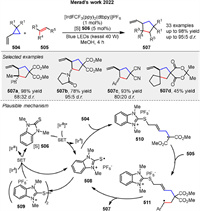

3.3. [4 + 2] cycloaddition