b State Key Laboratory of Discovery and Utilization of Functional Components in Traditional Chinese Medicine, Natural Products Research Center of Guizhou Province, Guizhou Medical University, Guiyang 550014, China

Pesticide is one of essential agricultural means of production, widely utilized in agriculture to control pests, including insects, fungi, weeds, and unwanted species that can harm crop production and storage. It plays a vital role in maintaining food security, safety of agricultural product, and ecological environmental security [1]. Therefore, constant efforts are being made by pesticide chemists in the development of new pesticides with effective, broad-spectrum bioactive, environmentally friendly, and low cost in the fields. Developing pesticide base on the privileged scaffold or structure concept is one of important strategy in drug discovery, which was first put forward by Evans et al. in 1988 [2]. Evolving as an activity moiety, the privileged scaffold has become a successful method for generating a molecule library of strong and specific ligands [3–5].

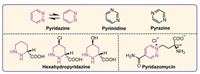

Pyridazine is an aromatic ring structure containing four carbon atoms and two nitrogen atoms in the ortho-position, which has two neutral resonance structures and is an isomer of heterocycle pyrimidine and pyrazine (Fig. 1). With the research of pyridazine, scientists refer to a six-membered heterocycle containing four carbon atoms and two adjacent nitrogen atoms as pyridazines family, such as pyridazine, hexahydropyridazine, pyridazinone, phthalazine, imidazopyridazine. It was synthesized by Fischer as early as 1886 [6], and later defined by Knorr [7], however, the natural pyridazine compounds (hexahydropyridazines, Fig. 1) were first found by Hassall′s team in 1971 [8] and the first natural aromatic pyridazine compound (pyridazomycin, Fig. 1) was reported by Zeeck in 1988 [9]. In recent years, pyridazine has gained increasing attention due to its unique structure, which results in pyridazine derivatives possessing a wide range of bioactive properties [10–13], including anti-anxiety [14], anti-alzheimer [15], anti-depressant [16–18], anti-inflammatory [19], anti-diabetic [20], anti-convulsant [21], anti-microbial [22–24], cardiovascular [25,26], and anti-cancer activities [27–31]. The structure-activity relationships (SARs) revealed that pyridazine can undoubtedly be considered a privileged structure due to its strong affinity for a great number of receptor proteins [11,32–35]. The numerous advantages of pyridazine as a privileged scaffold in drug design have been summarized in various studies [32–34,36], and these include (1) Pyridazine has a higher dipole moment (3.9 D) compared to pyridine (2.3 D), pyrimidine (2.4 D), and pyrazine (0.6 D), which improves both intermolecular and intramolecular interactions, as well as interactions between molecules and proteins. (2) The presence of two nitrogen atoms in pyridazine increases the hydrophilicity of small molecules. (3) Pyridazine (pKa = 2.0) has moderate basicity, less than pyridine (pKa = 5.2) but more than pyrimidine (pKa = 0.93) and pyrazine (pKa = 0.37), making it less likely to form salts with acids. (4) The two nitrogen atoms in pyridazine can simultaneously form two hydrogen bonds with residues, and also can engage in pi-pi and pi-hydrogen interactions with proteins. (5) Incorporating pyridazine into a bioactive molecule promotes crystal formation. (6) The pyridazine heterocycle is also considered a bioisosterism for benzene, azines, diazoles, pyrimidine, pyridine, and pyrazine, etc.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Resonance structures, isomers of pyridazine and natural pyridazine compounds. | |

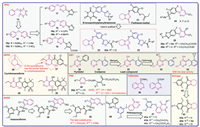

Due to above numerous advantages, many of pyridazine-containing drugs and pesticides were developed and broadly applied in medicine and agriculture. From 2010 to 2024, ten novel drugs (Fig. 2) were approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), including ponatinib [37], olaparib [37,38], talazoparib [37,39], relugolix [37,40,41], ensartinib dihydrochloride [42], risdiplam [42,43], tepotinib [42,44], fuzuloparib [45,46], deucravacitinib [46–48], and resmetirom [49,50]. However, only six pyridazine-containing pesticides (Fig. 2) have received International Standardization Organization (ISO) names according to the British Crop Production Council database (http://alanwood.net/pesticides/index_new_frame.html) from 2000 to 2024, such as cyclopyrimorate, flufenpyr, dioxopyritrione, propyrisulfuron, pyridachlometyl, and dimpropyridaz. Compared to drugs based on pyridazine, the development of pyridazine-based pesticides needs to attract more researchers to participate. Although existing reviews have addressed pyridazine chemistry in crop protection, they predominantly concentrate on the agricultural impacts of various pyridazine analogues and commercial pyridazine-based pesticides [51,52]. There is a scarcity of literature that delves into the advancements in the design and synthesis of pyridazine-derived pesticides. Consequently, a thorough summary of pyridazine applications in agriculture from 2000 to 2024 is imperative, and this review will serve as a valuable reference and source of inspiration for agricultural scientists in future research.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Pyridazine-containing of the PDA-approved drugs in 2010–2024 and pesticides received International Standardization Organization names in 2000–2024. | |

Effective weed management is essential for agricultural productivity and environmental stewardship, significantly impacting our capacity to fulfill future food demands [53]. The use of herbicides is the most economical and effective method in weed control strategies [54]. Since 2000, several pyridazine herbicides, including cyclopyrimorate, flufenpyr, dioxopyritrione, and propyrisulfuron (Fig. 2), have been developed, each targeting distinct mechanisms: homogentisate solanesyltransferase (HST), protoporphyrinogen Ⅸ oxidase (PPO), 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (4-HPPD), and acetohydroxyacid synthase (AHAS). Among them, cyclopyrimorate, flufenpyr, and propyrisulfuron are already on the market, and dioxopyritrione is anticipated to enter the market in the future. The present literatures reveal that the researches on pyridazine herbicides have concentrated on seven established targets, including phytoene desaturase (PDS), PPO, 4-HPPD, HST, AHAS, photosystem Ⅱ (PSⅡ), and acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACCase). Therefore, a detailed classification of pyridazine herbicides based on their modes of action was compiled to enhance researchers' comprehension of developments in this field.

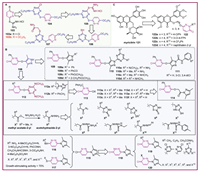

2.1. PDS inhibitorsAs a significant pyridazine derivative, pyridazinone has played an important role in crop protection chemistry. In 2005, Stevenson et al. explored the herbicide activity of various substitutions of pyridazinone at the 2 and 4-positions and the fixed methoxy group at the 5-position. Bioassays revealed that compounds 1 (Fig. 3) with a 3-CF3 or 3-OCF3-Ph group at the 4-position exhibited bleaching herbicide activity by targeting PDS. Meanwhile, the R group significantly affected the activity, for example 1a (3-F-Ph) > 1b (3-CF3-Ph) > 1c (Ph) > 1d (Me) ≫ 1e (4-CF3-Ph), 1f (t-Bu) [55]. The SARs indicated that compounds both containing 3-CF3-Ph group and six-membered heterocycle exhibited excellent inhibitory against PDS, which are essential for most commercial PDS inhibitor herbicides. Based on these features, the compound 6-methyl-4-(3-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)pyridazin-3(2H)-one 2 (Fig. 3) was selected as a lead compound for structural optimization to assess the herbicidal efficacy of various substitutions at the 2-position of the pyridazinone (3–6, Fig. 3). The results demonstrated that compounds 3a (R2 = CO2C2H5, 83.33%) and 3b (R2 = CH2CH2CH3, 97.83%) exhibited remarkable pre-emergence herbicidal activity against Digitaria adscendens at a dosage of 300 g ai/ha. Compound 3c (R2 = Me) showed 100% post-emergence inhibition to Brassia campestris at a dosage of 600 g ai/ha. Then, the impacts of various phenyl and benzyl groups at the 2-position for herbicidal activity were studied. Bioassays showed that compounds 6a, 6b, and 6c exhibited the excellent post-emergence herbicidal activities against D. adscendens and Echinochloa crus-galli at a dosage of 750 g ai/ha, which were better than those of compounds 4 and 5 (dihydropyridazinone derivatives). But, all of the compounds, substituted at the 2-position of compound 2 with alkyl, phenyl and benzyl, disfavor herbicidal activity compared to the positive control diflufenican [56,57]. Meanwhile, compounds 7 were designed from lead compound 3 by replacing the pyridazinone ring with a pyridazine ring and introducing arylamino or arylalkylamino groups at the 3-position of the pyridazine ring (Fig. 3). The herbicidal activity of these compounds showed that introducing arylalkylamino groups disfavor to herbicidal activity, however arylamino groups favor for activity. Among them, when n was 0, compounds exhibited herbicidal activity against B. campestris, such as the activity of compounds 7a-7e were greater than that of diflufenican at a dosage of 75 g ai/ha [58].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Pyridazine and pyridazinone herbicides targeting PDS. | |

To further enhance the activity of compounds 7, they drew upon Bernd Laber's finding, which indicated that substituting the N atom with an O atom could improve activity [59], the compounds 8 and 9 (Fig. 3) were designed and synthesized by replacing the N atom at the 3-position of compound 7 with an O atom. The findings demonstrated that the presence of small steric hindrance substituents at the 2-position of the benzyl moiety was essential for the herbicidal efficacy and bleaching properties of compounds 8. For instance, some compounds 8a–8d with H, CH3, Cl, CF3 showed ≥ 90% inhibition on B. campestris at a dosage of 750 g ai/ha in post-emergence tests. The presence of an electron-withdrawing group at the 4-position on the phenoxy group was found to be crucial for achieving high herbicidal activity of compound 9, such as compounds 9a–9d exhibited excellent herbicidal effectiveness as well as the positive control diflufenican against both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants in pre-emergence and post-emergence applications [60]. Subsequently, compound 9d was selected for further optimization, incorporating electron-withdrawing substituents (oxime, oxime ether and acylamino), which are similar to the cyano group, leading to the synthesis of the compounds 10 and 11 (Fig. 3). Oxime ether group substitutions 10 demonstrated higher herbicidal activity and bleaching effects compared to those with the acylamino group substitutions 11. Notably, compound 10a with oxime showed the best herbicidal activity (97.6% inhibition) against B. campestris at a dosage of 300 g ai/ha in the post-emergence tests, outperforming the commercial herbicide diflufenican [61].

In 2021, the Xi group conducted a molecular dynamics simulation investigation on compound 9d in relation to Synechococcus PDS, and designed compounds 12 (Fig. 3) employing a computational structure-based optimization strategy. Among them, compound 12a showed remarkable herbicidal activity at a dosage of 750 g ai/ha in both pre-emergence and post-emergence applications. This investigation underscored the significance of the methyl substituent at the 6-position of the pyridazine moiety for herbicidal activity, as well as the importance of substituents at the 4-position on the phenoxy group in influencing the bleaching efficacy of the compounds. The comprehensive analysis presented suggests that the most favorable substituents for the 4-position on the phenoxy moiety of compounds 12 are those that exhibit electron-withdrawing characteristics, such as CN, F, and CF3 [62]. In our group works, the pyridine moiety of the commercial herbicide diflufenican was replaced with pyridazine by scaffold hopping strategy and obtained compounds 13 and 14 (Fig. 3). Pre-emergence herbicidal activity tests revealed that compound 14a with a 2,4-diF substitution achieved 100% inhibition rates against the roots and stems of Portulaca oleracea and E. crus-galli at a concentration of 100 µg/mL, surpassing diflufenican. Additionally, compound 14a and diflufenican exhibited similar herbicidal activity against broadleaf weeds (100% inhibition) in post-emergence tests, outperforming the commercial herbicide norflurazon and the compounds 13 at a dosage of 75 g ai/ha. It suggests that a Cl atom at the 6-position is a crucial group for bioactivity [63].

Taken together, a lot of researches on targeting PDS underscore that the 3-CF3-phenyl moiety serves as a crucial active element, capable of being strategically placed at the 3/4-position of pyridazine and the 2/4-position of pyridazinone, and principal modification sites are identified at the 3, 4, and 6-positions in pyridazine, as well as the 2, 4, and 6-positions in pyridazinone. These findings provide a scientific foundation for the future development of new PDS inhibitor herbicides.

2.2. PPO inhibitorsProtoporphyrinogen Ⅸ oxidase (PPO) is a key enzyme in plant chlorophyll biosynthesis pathways, catalyzes the conversion of colorless protoporphyrinogen Ⅸ into the highly conjugated protoporphyrin Ⅸ. Diphenyl ethers (DPEs) represent a significant category of PPO inhibitors, with several compounds from this class having been formulated as commercial herbicides [64]. In 2002, the skeleton structure 3-benzoxy-pyridazine 15 (Fig. 4) was synthesized by replacing one of the phenyl groups in DPE with a pyridazine ring. Concurrently, various substituents including CF3 or NO2 or CH3 and NH(Me)2 or alkoxy groups (OMe, OCH2CH=CH2, OCH(CH3)2, and OCH2C≡CH) were introduced on the benzene and pyridazine ring respectively, resulting in the corresponding structures 16 (Fig. 4). Bioassay results showed that 16a and 16b exhibited significant pre-emergence herbicidal activity at a spraying mass fraction of 1 × 10–5, with inhibition rates of 96.6%, 97.1% and 78.3%, 79.3% against rape roots and E. crus-galli, respectively [65]. Subsequently, the researchers enhanced the efficacy of compounds 16 by substituting the R group at the 6-position with a pyrazole moiety and exploring various substituents on the benzene ring (compounds 17–19, Fig. 4). Preliminary bioassays indicated that compounds 18a and 18b, with no substitution on pyrazole and 4-Cl or 4-methyl substitutions on the benzene ring, exhibited excellent inhibition percentages (both 94%) against B. campestris at a concentration of 10 µg/mL in pre-emergence tests [66,67]. Furthermore, a series of tetrahydropyridazine derivatives 22 and 23 (Fig. 4) were synthesized through a scaffold hopping strategy, which involved the fusion of the 2-F-4-Cl-5-isoxazolinylphenyl fragment (marked in blue) from compound 20 (Fig. 4) and the thiadiazolo[3,4a]pyridazine moiety (highlighted in pink) of the commercial herbicide fluthiacet-methyl 21 (Fig. 4). The ester-containing derivatives 22 exhibited superior herbicidal activity to their corresponding amide-containing derivatives 23 against Amaranthus retroflexus, Abutilon juncea, E. crus-galli and D. sanguinalis. Among them, compound 22a not only demonstrated remarkable inhibition to Nicotiana tabacum PPO (NtPPO) with the value of Ki = 21.8 nmol/L, but also showed superior herbicidal activity to the positive control fluthiacet-methyl at the dosages of 12−75 g ai/ha and with the significant safety to maize at a dosage of 75 g ai/ha [68]. In recent years, two novel series of compounds 24 and 25 (Fig. 4) have been effectively identified as PPO inhibitors based on the pyridazinone scaffold. It indicated that the compounds introducing benzothiazole 25 exhibited better herbicidal activity than the compound with benzene 24. Notably, compound 25a achieved over 80% inhibition and displayed broad-spectrum activity, while 25b exhibited excellent inhibitory against NtPPO, with a K value of 0.0338 µmol/L [69].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Pyridazine, pyridazinone, and imidazopyridazine herbicides targeting PPO, HPPD, HST, PSII, AHAS, ACCase, and unknown targets. | |

Dioxopyritrione (Fig. 2), the first triketone 4-HPPD inhibitor featuring a pyridazinone structure, was disclosed by Bayer Crop Science in 2012, and was officially given its ISO common name in 2021 [70]. In light of the structural features of triketone, a novel triketone 4-HPPD inhibitors were developed by Stevenson and colleagues, they posited that 2-alkyl-5‑hydroxy-pyridazinone exhibits characteristics analogous to those of cyclohexanedione 26 (Fig. 4), which serves as the principal active component of 4-HPPD inhibitors. Therefore, compounds 27–29 (Fig. 4) were synthesized through the incorporation of an arylformyl moiety at the 4-position of 2-alkyl-5‑hydroxy-pyridazinone to discover new 4-HPPD inhibitor herbicides. Among these compounds, those with small N-substituents, such as methyl or ethyl groups, demonstrated the highest levels of biological activity [55].

Cyclopyrimorate (Fig. 2), discovered by Mitsui Chemicals Agro, Inc., resulted from structural modification of the lead compound 32 (Fig. 4). Compound 32 was designed by substructure splicing of two pyridazine herbicides, pyridafol 30 and credazine 31 (Fig. 4). And then it was further optimized by varying substituents on the benzene ring and hydroxy to obtain compound 33 (Fig. 4). The SARs revealed that the substituents significantly affect the activity, for R10: 2-Me-6-cyclopropyl > 2-cyclopropyl > 2-cyclopropyl-5-Me, 2-cyclopropyl-3-Me, and 2-cyclopropyl-4-Me, for R11: H, propionyl, 4-Me-benzoyl, N-formylmorpholine > 2-formylnaphthalene, 2,4,6-trimethylphenylsulfonyl. Cyclopyrimorate with high stability, efficacy and bleaching symptoms was proved to be a potent herbicide for managing a broad range of rice weeds by blocking HST [71,72]. Furthermore, des-morpholinocarbonyl cyclopyrimorate 34 (Fig. 4), a metabolite of cyclopyrimorate was identified with more herbicidal activity and inhibition of A. thaliana HST than that of cyclopyrimorate, which suggests that cyclopyrimorate is a prodrug herbicide [72,73].

Due to the role of 2-cyanoacrylates are inhibitors of PSII electron transport, a series of pyridazine cyanoacrylates 35 (Fig. 4) were synthesized. Their herbicidal activity was tested at a dosage of 1.5 kg ai/ha against rape, amaranth pigweed, alfalfa, and hairy crabgrass in post-emergence tests. Some compounds showed 100% inhibition to rape and amaranth pigweed, especially, compound 35a exhibited excellent inhibition (95.7%) at a dosage of 375 g ai/ha against rape. The SARs indicated that bulky group of R12 (i-Pr > MeS) and electron-drawing group of R13 (Cl > EtO > N-morpholinyl) favor for activity [74].

Cinnoline, which is similar to phthalazine, is another unique pyridazine class structure. Two natural cinnoline derivatives, cinnoline-4-carboxamide 36 and cinnoline-4-carboxylic acid 37 (Fig. 4), isolated from Streptomyces strain KRA17–580, demonstrated notable phytotoxic activity against Digitaria ciliaris at different concentrations. Interestingly, compounds 37 demonstrated a more selective effect on D. ciliaris compared to compound 36 and was found to be an inhibitor of photosynthesis, damaging the stems and leaves. Therefore, compound 37 is a potential new bioherbicidal candidate for the development of more efficient herbicides. Nevertheless, elucidating the mechanisms of action for the compound 37 requires further investigation and validation [75].

2.4. AHAS and ACCase inhibitorsPropyrisulfuron (Fig. 2) is an innovative sulfonylurea herbicide that specifically inhibits AHAS, developed by Sumitomo Chemical Co., Ltd. in 2008. It is known for its exceptional safety profile, high efficacy, environment friendly selective action, and broad-spectrum effectiveness against both dicotyledonous and monocotyledonous weeds [76]. In addition, various sulfonylurea compounds with remarkable herbicidal activity against resistant weeds were synthesized by Sumitomo Chemical and compound 38 (Fig. 4) derived from imazosulfuron (Fig. 4) having effective herbicidal activity was identified. Remarkably, compound 38 represents an uncommon instance that did not demonstrate cross-resistance in relation to mutations occurring at the active site within the same chemical class. In order to enhance its herbicidal activity, the substituent effect on the imidazopyridazine ring was investigated to obtain compounds 39 (Fig. 4). It was found that substituents R14 with a chain length of 2–3 atoms were advantageous for AHAS inhibition, with the ethyl group and propyl group showing the most effective inhibition activity. In terms of R15, methyl group and Cl atom exhibited significant herbicidal activity [77]. In light of the characteristics of the active fragment pyrimidinylbenzoates 40 (Fig. 4), phthalazin-1(2H)-one derivatives 41 (Fig. 4) were designed by using the 4,6-dimethoxypyrimidin-2-oxy group to bear the benzopyridazinone (phthalazinone) as a novel AHAS inhibitors. Preliminary bioassay results indicated that compounds 41a–41c showed promising anti-AHAS and broad-spectrum herbicidal activities in post-emergence tests at a dosage of 150 g ai/ha. However, benzyl group of R17 disfavor for herbicidal activity [78].

Derivatives of 2-aryl-1,3-diones have been recognized as a novel category of ACCase inhibitors. Cederbaum and Krueger reported the herbicidal efficacy of compound 42 (Fig. 4), a member of the 2-aryl-1,3-diones derivatives. Subsequently, modifications were made at the 4-position of the aromatic ring and their post-emergence herbicidal activities were evaluated. It revealed that compounds 43 (Fig. 4) exhibited herbicidal activities against Avena fatua, Alopecurus myosuroides, Setaria faberi, and Lolium perenne at a dosage of 125 g ai/ha. The SARs manifested that a simple methyl group (R18 = CH3 at the 4-position 43b) exhibited the best activity, but showing severe cereal damage, with efficacy following the order 43b > 43a > 43c > 42 [79].

3. Insecticidal activityInsecticides serve as critical tools for agricultural producers and public health specialists, providing effective strategies for the management of pest populations. Nonetheless, the persistent demand for novel insecticidal agents is driven by the necessity for enhanced environmental safety, the evolution of regulatory frameworks, and the diversification of pest species [80]. Research indicates that the incorporation of lipophilic moieties enhances the insecticidal efficacy of oxadiazole [81]. Pyridazinone, characterized as a lipophilic moiety, has been developed into insecticides such as acaricide 44 and juvenoid 45 (Fig. 5A). Consequently, researchers conjugated a pyridazinone moiety to an oxadiazolyl group to enhance the solubility of oxadiazole and augment the insecticidal efficacy of the novel oxadiazolyl 3(2H)-pyridazinones. The oxadiazolyl 3(2H)-pyridazinones were modified on four chemical sites (R, R1, X1, and X2), resulting in compounds 46 (Fig. 5A). The SARs indicated that substituents such as X1, X2 = O, R = tert‑butyl, and R1 = substituted benzene ring, particularly R1 = 4-F-Ph or 4-Cl-Ph, were essential for the activity. Physicochemical parameters, such as molar refractivity, dipole moment, and logP were identified as three key factors influencing chronic growth effects against Ostrinia furnacalis (Guenee) and Pseudaletia separata (Walker) [82–84]. It was not until 2020, Dang et al. continued the modification of compound 44 by substituting its 4-(tert‑butyl)phenyl group with 2-phenyloxazole or 2-phenylthiazole moieties through an activity substructure splicing strategy, yielding compounds 47 (Fig. 5A). Compound 47a exerted potent insecticidal activity against Aphis fabae, with an LC50 value of 2.73 mg/L, which performed better insecticidal activity than that of compound 44 (5.46 mg/L) but inferior to that of the positive control imidacloprid (0.51 mg/L). Additionally, compound 47a displayed 96.9% fungicidal activity against Puccinia polysora at a concentration of 500 mg/L in vivo, outperforming the positive control pyridaben (50.0%). Therefore, the best substitution should be R2 = t-Bu, R3 = 4-Cl, R4 = H, and X1, X2 = S (compound 47a), and compounds 47b and 47c also exhibited remarkable activity [85].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Pyridazine and pyridazinone insecticides. | |

Benzoylphenylureas with excellent insecticidal activity have attracted considerable interests for pesticide chemist, and the SARs revealed that the benzoylurea moiety plays a critical role to the activity. In the present, the N-2,6-difluorobenzoylurea moiety of compounds 48 (Fig. 5B) was used as a key skeleton, and further modified by Cao et al., through transforming the linkage position on the pyridazinone from the 5-position to the 4-position to obtain compounds 49 (Fig. 5B). Bioassays showed that the mortality rates of compounds 49b–49f (Fig. 5B) were 72%, 50%, 43%, 53%, and 30% at 500 mg/dm3 against the armyworm and P. separata, while compounds 49a, 49g, and 49h had no activity (Fig. 5B). It revealed that ethyl at the 2-position of the pyridazinone ring exhibited the most effective [86]. Furthermore, Wang et al. retained the key N-2,6-difluorobenzoylurea moiety of the commercial both flufenoxuron 50 and hexaflumuron 51 (Fig. 5B) and applied pyridazine as a bioisosterism to replace the benzene ring to obtain pyridazine compounds 52 (Fig. 5B). Compound 52a (R9 = OCH2CF3) achieved 80% mortality in oriental armyworms, comparable to that of the commercial hexaflumuron at a concentration of 10 mg/L, while compound 52b (R9 = 4-Br-phenoxy) exhibited the highest larvicidal activity (100%) against mosquitoes at a concentration of 2 mg/L [87].

For enhancing the insecticidal potency of compound 53 against aphids, Buysse et al. designed some novel pyridine-pyridazine compounds 54–61 containing amides, hydrazones, and hydrazides moieties (Fig. 5C). Among them, compound 55a (LC50 = 0.02 ppm) exhibited comparable activity with the positive control imidacloprid against Aphis gossypii, while the other compounds did not show satisfactory insecticidal activity against Myzus persicae and A. gossypii. The SARs indicated that the compounds with small alkyl amide group showed more activity than the compounds containing aryl counterparts, such as compounds 56a and 56b demonstrated the excellent insecticidal activity against both M. persicae and A. gossypii. Meanwhile, modification of the pyridine or pyridazine rings led to decreased activity against A. gossypii and M. persicae. In addition, substituting the amide linker with hydrazones was tolerated, whereas replacement with hydrazides led to reduced activity in the compounds [88].

As a vital target for parasiticides and insecticides, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors are widely distributed in the central and peripheral nervous systems of insects. Gabazine 62 (Fig. 5D) has been confirmed to possess moderate antagonist activity against insect GABA receptors [89,90]. In order to enhance its antagonist activity against insect GABA receptors, different aryl groups were introduced at the 3-position on the pyridazine ring to prepared compounds 63 (Fig. 5D). Compound 63a (R18 = 4-biphenyl) displayed approximately 50% inhibition of GABA-induced fluorescence changes against small brown planthopper and common cutworm GABA receptors at a concentration of 10 µmol/L. Compound 63b (R18 = 2-naphthyl) showed complete inhibition of GABA-induced membrane potential changes in common cutworm and small brown planthopper GABA receptors at a concentration of 100 µmol/L. GABA concentration-response curve analysis revealed that compound 63c (R18 = 3-thienyl) is a competitive GABA receptor antagonist [90]. Subsequently, the compounds 64a–64c (Fig. 5D), replacing the sidechain carboxyl group at the 1-position with a cyano group and introducing a cyclobutyl group at the 4-position of the pyridazine ring, did not significantly alter activity against insect GABA receptors. Phosphonopropyl group resulted in decreased activity in common cutworm and small brown planthopper GABA receptors, but increased activity in housefly GABA receptors [91,92]. Recently, the researchers continued to modify the 3,5-positions of the pyridazine ring and 1-position sidechains (shorten one carbon) to prepare compounds 65 and 66 (Fig. 5D). Bioassays results indicated that compounds 66a–66c exhibited strong antagonism against housefly and common cutworm RDL receptors, with IC50 values ranging from 2.2 µmol/L to 24.8 µmol/L. Moreover, most of the 1,3-disubstituted pyridazines showed moderate larvicidal activity in common cutworms at a concentration of 100 mg/kg. The SARs indicated that the compounds shorten a methylene (66) at the 1-position of the pyridazine ring exhibited more effectively maintain stable binding of 1,6-dihydro-6-iminopyridazines in insect ionotropic GABA receptors than gabazine, however the introduction of a substituent at the 5-position disfavor for inhibition of housefly and common cutworm RDL receptors [93].

Dimpropyridaz (Fig. 2) is an insecticide with pyrazole carboxamide developed by BASF and was registered in Australia and Korea in 2021 [94]. It demonstrated significant insecticidal activity against A. gossypii with an LC50 value of 1.91 mg/L for 72 h post-exposure, and accompanied notable poisoning symptoms, including shriveling and dehydration. Meanwhile, the feeding rate of A. gossypii decreased by 71.67% after 72 h of exposure at a concentration of 50.33 mg/L [95]. Furthermore, it was confirmed that dimpropyridaz maybe a pro-insecticide because that its metabolism pyridazine pyrazolecarboxamide can block signaling, thereby inhibit the firing of chordotonal organs at a location upstream of the TRPV (Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid) channels [96]. Changing the substituent position approach was employed from the 4-position to 3-position of pyridazine ring to obtain compounds 67 (Fig. 5E). The insecticidal activity results indicated that compounds 67a and 67b with 4-pyridazinyl moiety demonstrated remarkable insecticidal activity against M. persicae. Nevertheless, Het = 3-pyridazinyl resulted in a total loss of insecticidal activity [94]. Furthermore, pyridazinone derivatives 68 and 69 (Fig. 5E) containing 2-Cl-quinoline moiety were designed and synthesized and exhibited notable insecticidal toxicity compared to the positive control imidacloprid against both field and lab strains of Culex pipiens L. larvae [97].

4. Antifungal and antibacterial activitiesPlant diseases caused by fungi and bacterial significantly impact agricultural output, leading to destroy over 30% of all food crops worldwide and resulting in serious economic and ecological risks in the agricultural field [98,99]. The use of chemical fungicides and bactericides is one of efficient, rapid and economical way to control plant diseases. Among them, the development and application of pyridazine-based antifungal and antibacterial agents has still attracted the focus of pesticide scientists. In present, novel pyridazinone-based antifungal agents 70 (Fig. 6A) were designed by combining pyridazinone ring and 1,3,4-thiadiazole moiety. Compounds 70a and 70b showed 100% inhibitory against Puccinia recondita at a concentration of 500 µg/mL [100]. Further modification found that compounds 70c and 70d showed the excellent activity at a concentration of 100 µg/mL. The quantitative SARs revealed that hydrophobicity is critical for activity, such as the 2,4-diCH3 of R1 favors activity, while the activity order of R2 substituents as following, 3-CF3 > 2-F > H [101,102]. Then, replacing the 1,3,4-thiadiazole of compounds 70 with 1,3,4-oxadiazole to create compounds 71 (Fig. 6A), which exhibited similar fungicidal activity with compounds 70. It further confirms that the 1,3,4-oxadiazole ring can be considered a bioisosterism of the 1,3,4-thiadiazole ring [102]. Modifications at the 2-position of 5‑chloro-6-phenylpyridazin3(2H)-one 72 led to three series of pyridazinone compounds 73–75 (Fig. 6A). Compounds 73a, 75a and 75b exhibited excellent antifungal activities against Gibberella zeae, comparable or better than the positive control hymexazol. Comparing compounds 74 with compounds 75, the compounds containing sulphone group showed better activity than thioether unit [103].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. Pyridazine, pyridazinone, and imidazopyridazine derivatives as antifungal and antibacterial agents. | |

Pyridachlomethyl (Fig. 6B), a novel tubulin dynamics modulator fungicide developed by Sumitomo chemical company [104], received an ISO name from the British Crop Production Council in 2017 (http://alanwood.net/pesticides/index_new_frame.html). As a first-in-class molecule, it is the first commercial product receiving initial registration in Japan in 2023 [105]. Notably, pyridachlomethyl does not exhibit any cross-resistance with other types of fungicides, such as respiratory inhibitors, tubulin polymerization inhibitors, and ergosterol biosynthesis inhibitors in Zymoseptoria tritici [106]. In fact, the development of pyridachlomethyl includes four stages of evolution of chemical structures from compound 76 (BAS600F, Fig. 6B) with potential fungicidal activity against Pyricularia oryzae, Podosphaera xanthii, Botrytis cinerea, and Alternaria brassicicola. However, the structure of compound 76 is markedly complex as a crop protection agent. Thus, the researchers retained pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine pharmacophore of compound 76 and prepared compound 77, then replaced pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine with pyrimidone through bioisosteric transformations to obtain 78. Whereafter, further simplification was performed with pyridazine to change pyrimidone and discovered compound 79 (Fig. 6B). Although it was eventually found that compounds 79 and pyridachlomethyl exhibited similar fungicidal activity. Finally, more economical and safer of pyridachlomethyl was found by simplification of the groups at the two benzene rings [105,107]. In addition, compound 79 was identified as a bicyclic tubulin polymerization promoter [108]. So, various pyridazine derivatives (80–83, Fig. 6B) through modifications at the 3, 4, 5, and 6 positions on the pyridazine ring were respectively synthesized. Most of these compounds showed remarkable fungicidal activity against Mycosphaerella graminicola (wheat leaf blotch), B. cinerea (gray mold), and Alternaria solani (tomato and potato early blight) and the active orders were observed, such as 79 > 80d > 80b > 80c > 80a; 79 > 81c > 81b > 81d > 81a; 82a≈82b > 82f > 82c > 82e > 82d; and 82a > 83c > 79 > 83b > 83a > 83d [109]. Overall, pyridazines with a chlorine atom at the 3-position and a methyl group at the 6-position inhibit the most antifungal activity. Meanwhile, two halogen substitutions at the 2,6-positions of the 4-position phenyl group significantly affect the activity. Furthermore, modification with a pyridyl group or 4-substituted phenyl group at the 5-position of pyridazine ring can enhance the antifungal activity.

Natural products are the source of the development of new drugs, inspired by quaternary benzo[c]phenanthridine alkaloids (QBAs) compounds 84 and 85 were obtained in turn by simplifying the structure of the QBAs (Fig. 6C). The antifungal activity of these compounds was similar to or even more than that of QBAs. Based on these findings and the iminium moiety (C=N+) is a crucial group determining the antibacterial and antifungal activity [110,111], a series of novel phthalazine analogs 86 containing C=N+ (Fig. 6C) were designed and synthesized, most of compounds exhibited outstanding inhibition activity against nearly all eight phytopathogenic fungi (Fusarium solani, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum, Fusarium bulbigenum, Alternaria alternata, Colletotrichum gloeosporioides, Alternaria brassicae, A. solani, and P. oryzae), which significantly better than both lead compounds, chelerythrine and sanguinarine (Fig. 6C). Especially, compounds 86a and 86b showed the most potent activity against eight fungi, demonstrating EC50 values of approximately 4.6 µg/mL. Moreover, compound 86b at a concentration of 25.0 µg/mL not only effectively controlled the C. gloeosporioides infection in apples but also disrupted the structures of the hypha and cell membrane. The SARs revealed that the presence of electron-withdrawing groups at the p-position, except of Br and I, enhances activity against most or all fungi such as Cl, F, CF3, NO2, and CN, whereas electron-donating groups such as Me, Et, and MeO only cause a slight change (increase or decrease) in the activity for most of the fungi, whether it is at the o-, m-, or p-position. Above all, the 2-phenylphthalazin-2-ium core demonstrates promising potential as a lead compound for the development of novel QBA-like fungicides in plant protection [112,113].

As a natural lead compound, glyantrypine-family alkaloid 87 was modified through molecular splicing strategy to afford compounds 88 and 89 (Fig. 6D). Only compound 88a exhibited an inhibition ratio exceeding 90% against Physalospora piricola, similar to the positive control carbendazim and chlorothalonil at a concentration of 50 µg/mL [114]. Chalcones serve as a crucial precursor in the biosynthesis of flavonoids and are widely utilized in fungicides [115], which was merged with the pyridazine ring to create three series of compounds 90–92 (Fig. 6D). Bioassays revealed that some compounds showed remarkable antifungal and antibacterial activities, especially, compound 90a possessed the most effective antibacterial activity, with an EC50 value of 78.89 µg/mL against X. campestris pv. citri, which was superior to bismerthiazol (EC50 = 86.72 µg/mL). Moreover, compound 90b demonstrated outstanding inhibitory activity against B. cinerea (100%) and Rhizoctonia solani (85.67%) at a concentration of 100 µg/mL, superior to the positive control azoxystrobin (87.65% and 76.30%) [116].

In the same year, various pyridazine-3(2H)-one derivatives 94–96 were synthesized from a potential new fungicide 93 (Fig. 6E). Antifungal tests showed that the activity of the dihydropyridazinone derivatives 94a and 94b was superior to that of the pyridazinone 93 and pyridazine derivatives 96 at a concentration of 250 µg/mL against F. solani and all of them were less effective than that of lead compound 93. It suggests that introducing pyridazine ring was not an optimal strategy [117]. Another set of dihydropyridazinone derivatives 97–100 (Fig. 6E) were also found to be relatively weak in preliminary tests against threatening pathogenic bacteria at a concentration of 400 µg/mL [118]. Imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine scaffold is rarely reported in pyridazine-based antifungi, a range of 3,6-disubstituted imidazo[1,2-b]pyridazine derivatives 101 (Fig. 6E) were synthesized and their antifungal properties were evaluated. Among them, compounds 101a–101d exhibited broad spectrum antifungal activity, outperforming the positive control hymexazol against A. alternata, Corn Curvalaria Leaf Spot, A. brassicae, and P. oryzae. Then, compounds 102 (Fig. 6E) were created by further modifying the 6-position of compound 101a. Interestingly, compound 102a with R26 as a methyl group showed the best antifungal affect compared to other compounds and two positive controls. The SARs indicated that substituents on the benzene ring and at the 6-position of the pyridazine ring significantly influence activity [113,119].

5. Plant growth regulating and antiviral activitiesAlthough pyridazine-containing pesticides have been commercialized, pyridazine-containing compounds have not been applied as plant growth regulators and antiviral agents due to limited research on this field. Yengoyan et al. designed and synthesized various pyridazine and pyridazinone derivatives from 2016 to 2022, focusing on modifications at the 3 and 6 positions of pyridazine, as well as the 2 and 6 positions of pyridazinone, respectively. Initially, compound 103b was screened from 103a and 103b, and then it was further modified to orderly afford compounds 104–107 (Fig. 7A). Among them, compounds 103a, 103b, and 107 demonstrated significant growth stimulatory effects on common bean plants at a concentration of 25 mg/L. Furthermore, compound 103a can stimulate the growth of vegetative organs, compound 103b can be recommended for shorten the juvenile time, and compound 107 accelerated flowering and fruit production and shorten the juvenile time [120].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. Plant growth regulating and antiviral activity of pyridazine and pyridazinone derivatives. | |

In addition, compound 108 was used as a lead compound to investigate various N-substitutions of the pyrazole ring, resulting in compounds 109–111 (Fig. 7B). Meanwhile, two compounds 112a and 112b (Fig. 7B) were obtained by replacing the pyrazole ring of compound 108 with the triazinyl group, while introducing benzyl and 2-(3,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrazol-1-yl)−2-oxoethyl. Following, the various X groups (X3–X11), orderly converted from acetohydrazide-2-yl group (X2) and methyl acetate-2-yl group (X1) were replaced the triazinyl group of compounds 112, while retaining benzyl and phenyl at the 2-position, resulting in compounds 113 and 114 (Fig. 7B). Bioassays revealed that most of compounds 109–114 except for compounds 111 showed notable plant growth stimulant activity (> 70%), including compounds 109a–109d, 110a–110d, 112a, 112b, 113a–113f and 114 [121,122]. Furthermore, some chain groups were introduced into the 3-position of pyridazine of compound 115 with S or hydrazine as a linker to synthesize compounds 116 and 117 (Fig. 7B). When R8 were NH2, 4-MeOC6H4CH=N, 3-NO2C6H4CH=N, PhCONH, CH3CH2NHCSNH, 3-ClC6H4NH, 4-MeC6H4SO2NH, and X were X4, X6, X7, X9, X10 and X11, these compounds showed plant growth stimulant activity above 70% [123,124]. Pyrazolyl-pyridazinone derivatives (compounds 119 and 120, Fig. 7B) were obtained by introducing a six-membered aromatic heterocycle, alkane, or X groups at the 2-position of intermediate 118 (Fig. 7B), which was formed through oxidation of compound 115. Some compounds demonstrated 50% to 94% stimulating effect on plant growth against the seeds and seedlings of the common bean, such as R9 were CH3, C2H5, CH2CONH2, 2‑chloro-4-methylpyrimidine-6-yl, triazinyl and 6-Cl-pyridazinyl, and X were X2, X3, X5, X7, X9, and X10 [125,126]. These findings demonstrate that pyridazine and pyridazinone are promising scaffolds for the design of plant growth regulators.

Plant virus diseases, often referred to as the "cancer" of plants, have caused severe damage to crops worldwide, leading to enormous global economic losses [127]. Pyridazine was recognized as a privileged scaffold for development of pesticides, however there is still no commercial pyridazine-based antiviral agents, and only limited researches refer to their antiviral activity. Compared to 89, phthalazinoquinazolines 88 exhibited excellent anti-TMV activity at a concentration of 500 µg/mL. Especially, compound 88a showed the best antiviral activity due to inhibiting TMV particle extension during assembly. Meanwhile, compound 88b containing long-chain alkyl groups, displayed significantly higher anti-TMV activity than those with short-chain alkanes. These results indicated that the introduction of heterocycles and long-chain alkyl groups are beneficial for bioactivity [114]. In 2024, compounds 122 (Fig. 7C) were synthesized based on the active splicing principle, starting with natural product myricetin 121 (Fig. 7C) and incorporating pyridazinone moiety. The antiviral activity tests against TMV indicated that compounds 122a, 122b and 122d displayed promising curative effects, with EC50 values of 131.6, 138.5, and 118.9 mg/mL, respectively, outperforming the control ningnanmycin (235.6 mg/mL). Furthermore, compounds 122c and 122d exhibited strong protective activity with EC50 values of 117.4 and 162.5 mg/mL, respectively, superior to the control ningnanmycin (263.2 mg/mL) [128].

6. Summary and outlookPyridazines have been proven to possess broad-spectrum bioactivity and useful for controlling pests, weeds, and plant diseases in agriculture. This review reports six notable pyridazine-containing pesticides including cyclopyrimorate, flufenpyr, dioxopyritrione, propyrisulfuron, pyridachlometyl, and dimpropyridaz, which have been received ISO names from 2000 to 2024. Among them, cyclopyrimorate, flufenpyr, propyrisulfuron, and dioxopyritrione are herbicides, while pyridachlometyl and dimpropyridaz are used as an insecticide and fungicide, respectively. The survey statistics revealed that the researches primary focus on herbicides (36.9%), followed by insecticides (26.2%) and fungicides and bactericide (24.6%) over the past two decades. Nevertheless, the antiviral applications of pyridazine remain largely unexplored, with few studies published and no commercial antiviral agents developed from 2000 to 2024. Furthermore, there are four main pyridazine skeletons for pyridazine derivatives, including pyridazine, pyridazinone, phthalazine, and imidazopyridazine. Of which, pyridazine and pyridazinone have gained more attention in the field of pesticide development compared to phthalazine and imidazopyridazine. Notably, both pyridazine and pyridazinone have four modifiable positions that are 3, 4, 5, and 6 positions for pyridazine and 2, 4, 5, and 6 positions for pyridazinone. Especially, the 3 and 6 positions in pyridazine and the 2, 4, and 6 positions in pyridazinone are the most common modification sites and easy to introduce various substituents due to the electron-deficient property of pyridazine and pyridazinone rings, which can obtain a variety of pyridazine and pyridazinone derivatives. Thereby, the multifarious derivations of privilege scaffold pyridazine plays a crucial role for the development of pesticides.

Despite numerous studies and significant advancements in the development of pesticides based on the pyridazine scaffold, the number of papers in the field of pesticides remain significantly lower compared to that in the pharmaceutical field. This discrepancy may be attributed to the challenges associated with developing structural diversity of pyridazine, particularly in simultaneously introducing various substituents at the 4,5-positions while also requiring a much lower production cost for pesticides. Consequently, it is necessary to develop highly efficient and cost-effective synthetic methods for the constructing multi-substitutive pyridazine derivatives. Fortunately, several pyridazine natural products lower environmental and mammalian toxicity have been discovered [75,129–135], which provide novel privilege scaffold in the development of structural diversity pesticides base on the natural pyridazine derivatives. Additionally, the mechanisms of action for pyridazine derivatives in antiviral, insecticidal, antifungal, antibacterial, and plant growth regulator applications remain unclear. Furthermore, limited research has been conducted on their targets in herbicides. Therefore, future studies should focus more on comprehensive investigation of their biological mechanisms. This represents that pyridazine is a distinct and promising privilege scaffold for the development of new pesticides in 21st-century.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statementChao Chen: Writing – original draft, Investigation. Wang Geng: Writing – original draft. Ke Li: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Qiong Lei: Investigation. Zhichao Jin: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Xiuhai Gan: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Resources, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

AcknowledgmentsThe financial support from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFD1700102), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32472608), the Guizhou Provincial Fundation for Excellent Scholars Program (No. GCC[2023]069), the Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects (No. Qiankehezhongyindi [2024]007), and the Guizhou Province Program of Major Scientific and Technological (No. Qiankehechengguo [2024]zhongda007), the Central Government Guides Local Science and Technology Development Fund Projects (No. Qiankehezhongyindi (2023) 001).

| [1] |

Y. Abubakar, H. Tijjani, C. Egbuna, et al., Pesticides, history, and classification, in: C. Egbuna, B. Sawicka (Eds.), Natural Remedies for Pest, Disease and Weed Control, Academic Press, 2020, pp. 29–42.

|

| [2] |

B.E. Evans, K.E. Rittle, M.G. Bock, et al., J. Med. Chem. 31 (1988) 2235-2246. DOI:10.1021/jm00120a002 |

| [3] |

M.E. Welsch, S.A. Snyder, B.R. Stockwell, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14 (2010) 347-361. |

| [4] |

H.Y. Zhao, J. Dietrich, Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 10 (2015) 781-790. DOI:10.1517/17460441.2015.1041496 |

| [5] |

P. Schneider, G. Schneider, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 7971-7974. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702816 |

| [6] |

S. Kang, H.K. Moon, Y.J. Yoon, H.J. Yoon, J. Org. Chem. 83 (2018) 1-11. |

| [7] |

A. Smith, J. Chem. Soc. Trans. 57 (1890) 643-652. |

| [8] |

K. Bevan, J.S. Davies, C.H. Hassall, R.B. Morton, D.A.S. Phillips, J. Chem. Soc. C (1971) 514-522. |

| [9] |

R. Grote, Y.L. Chen, A. Zeeck, et al., J. Antibiot. 41 (1988) 595-601. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.41.595 |

| [10] |

B.U.W. Maes, Chapter 13 Pyridazines, Tetrahedron Organic Chemistry Series, Elsevier, 2007, pp. 541–585.

|

| [11] |

Z.Q. Liu, Q. Zhang, Y.L. Liu, et al., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 111 (2024) 117847. |

| [12] |

Y.T. Han, J.W. Jung, N.J. Kim, Curr. Org. Chem. 21 (2017) 1265-1291. DOI:10.2174/1385272821666170221150901 |

| [13] |

S. Dubey, P.A. Bhosle, Med. Chem. Res. 24 (2015) 3579-3598. DOI:10.1007/s00044-015-1398-5 |

| [14] |

Y. Imamura, A. Noda, T. Imamura, et al., Life Sci. 74 (2003) 29-36. |

| [15] |

S. Alghamdi, M. Asif, Eurasian Chem. Commun. 3 (2021) 435-442. |

| [16] |

M.C. Costas-Lago, P. Besada, F. Rodríguez-Enríquez, et al., Euro. J. Med. Chem. 139 (2017) 1-11. |

| [17] |

C.G. Wermuth, G. Schlewer, J.J. Bourguignon, et al., J. Med. Chem. 32 (1989) 528-537. DOI:10.1021/jm00123a004 |

| [18] |

R.T. Lewis, W.P. Blackaby, T. Blackburn, et al., J. Med. Chem. 49 (2006) 2600-2610. DOI:10.1021/jm051144x |

| [19] |

X.Y. Sun, C. Hu, X.Q. Deng, et al., Euro. J. Med. Chem. 45 (2010) 4807-4812. |

| [20] |

B. Bindu, S. Vijayalakshmi, A. Manikandan, Euro. J. Med. Chem. 187 (2020) 111912. |

| [21] |

L.P. Guan, X. Sui, X.Q. Deng, Y.C. Quan, Z.S. Quan, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45 (2010) 1746-1752. |

| [22] |

S.A. Rizk, S.S. Abdelwahab, A.A. El-Badawy, J. Heterocycl. Chem. 56 (2019) 2347-2357. DOI:10.1002/jhet.3622 |

| [23] |

A.H. Moustafa, H.A. El-Sayed, R.A. Abd El-Hady, A.Z. Haikal, M. El-Hashash, J. Heterocycl. Chem. 53 (2016) 789-799. DOI:10.1002/jhet.2316 |

| [24] |

H.S. Ibrahim, W.M. Eldehna, H.A. Abdel-Aziz, M.M. Elaasser, M.M. Abdel-Aziz, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 85 (2014) 480-486. |

| [25] |

M. Asif, A. Singh, A.A. Siddiqui, Med. Chem. Res. 21 (2012) 3336-3346. DOI:10.1007/s00044-011-9835-6 |

| [26] |

M.C. Lucas, N. Bhagirath, E. Chiao, et al., J. Med. Chem. 57 (2014) 2683-2691. DOI:10.1021/jm401982j |

| [27] |

P. Brehova, E. Řezníčková, K. Skach, et al., J. Med. Chem. 66 (2023) 11133-11157. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c00575 |

| [28] |

B.B. Mao, S.Y. Gao, Y.R. Weng, L.R. Zhang, L.H. Zhang, Euro. J. Med. Chem. 129 (2017) 135-150. |

| [29] |

T.L. Chen, A.S. Patel, V. Jain, et al., J. Med. Chem. 64 (2021) 12469-12486. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01733 |

| [30] |

P. Břehová, E. Řezníčková, K. Škach, et al., J. Med. Chem. 66 (2023) 11133-11157. |

| [31] |

T. Taniguchi, I. Yasumatsu, H. Inagaki, et al., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 15 (2024) 1010-1016. DOI:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.4c00030 |

| [32] |

C.G. Wermuth, Med. Chem. Commun. 2 (2011) 935-941. DOI:10.1039/c1md00074h |

| [33] |

A. Garrido, G. Vera, P.O. Delaye, C. Euro, J. Med. Chem. 226 (2021) 113867. |

| [34] |

Z.X. He, Y.P. Gong, X. Zhang, L.Y. Ma, W. Zhao, Euro. J. Med. Chem. 209 (2021) 112946. |

| [35] |

M. Jaballah, R. Serya, K. Abouzid, Drug Res. 67 (2017) 138-148. |

| [36] |

N.A. Meanwell, Med. Chem. Res. 32 (2023) 1853-1921. DOI:10.1007/s00044-023-03035-9 |

| [37] |

D.G. Brown, H.J. Wobst, J. Med. Chem. 64 (2021) 2312-2338. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.0c01516 |

| [38] |

Olaparib, Cancer Discov. 5 (2015) 218. |

| [39] |

A.C. Flick, H.X. Ding, C.A. Leverett, et al., J. Med. Chem. 61 (2018) 7004-7031. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00260 |

| [40] |

A. Markham, Drugs 79 (2019) 675-679. DOI:10.1007/s40265-019-01105-0 |

| [41] |

F. Barra, M. Seca, L. Della Corte, P. Giampaolino, S. Ferrero, Drugs Today 55 (2019) 503-512. DOI:10.1358/dot.2019.55.8.3020179 |

| [42] |

A.C. Flick, C.A. Leverett, H.X. Ding, et al., J. Med. Chem. 65 (2022) 9607-9661. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00710 |

| [43] |

H. Ratni, R.S. Scalco, A.H. Stephan, ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 12 (2021) 874-877. DOI:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.0c00659 |

| [44] |

A. Markham, Drugs 80 (2020) 829-833. DOI:10.1007/s40265-020-01317-9 |

| [45] |

A. Lee, Drugs 81 (2021) 1597. DOI:10.1007/s40265-021-01585-z |

| [46] |

S.P. France, E.A. Lindsey, E.L. McInturff, et al., J. Med. Chem. 67 (2024) 4376-4418. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.3c02374 |

| [47] |

S.M. Hoy, Drugs 82 (2022) 1671-1679. DOI:10.1007/s40265-022-01796-y |

| [48] |

D.S. Treitler, M.C. Soumeillant, E.M. Simmons, et al., Org. Process Res. Dev. 26 (2022) 1202-1222. DOI:10.1021/acs.oprd.1c00468 |

| [49] |

S.J. Keam, Drugs 84 (2024) 729-735. DOI:10.1007/s40265-024-02045-0 |

| [50] |

S. Braner, C EN Glob. Enterp. 102 (2024) 13. |

| [51] |

M. Asif, M. Allahyani, M.M. Almehmadi, A.A. Alsaiari, Curr. Org. Chem. 27 (2023) 814-820. DOI:10.2174/1385272827666230809094221 |

| [52] |

C. Lamberth, J. Heterocycl. Chem. 54 (2017) 2974-2984. DOI:10.1002/jhet.2945 |

| [53] |

J.H. Westwood, R. Charudattan, S.O. Duke, et al., Weed Sci. 66 (2018) 275-285. DOI:10.1017/wsc.2017.78 |

| [54] |

B.S. Chauhan, Front. Agron. 1 (2020) 3. |

| [55] |

T.M. Stevenson, B.A. Crouse, T.V. Thieu, et al., J. Heterocycl. Chem. 42 (2005) 427-435. DOI:10.1002/jhet.5570420310 |

| [56] |

H. Xu, X.M. Zou, Y.Q. Zhu, et al., Pest Manag. Sci. 62 (2006) 522-530. DOI:10.1002/ps.1195 |

| [57] |

H. Xu, X.H. Hu, Y.Q. Zhu, et al., Sci. China Chem. 53 (2010) 157-166. DOI:10.1007/s11426-010-0014-2 |

| [58] |

H. Xu, X.H. Hu, X.M. Zou, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 56 (2008) 6567-6572. DOI:10.1021/jf800900h |

| [59] |

B. Laber, G. Usunow, E. Wiecko, et al., Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 63 (1999) 173-184. |

| [60] |

H. Xu, Y.Q. Zhu, X.M. Zou, et al., Pest Manag. Sci. 68 (2012) 276-284. DOI:10.1002/ps.2257 |

| [61] |

X.M. Zou, C.R. Fu, X. Wang, et al., J. Heterocycl. Chem. 54 (2017) 670-676. DOI:10.1002/jhet.2640 |

| [62] |

L.J. Yang, D.W. Wang, D.J. Ma, et al., Molecules 26 (2021) 6979. DOI:10.3390/molecules26226979 |

| [63] |

C. Chen, Q. Lei, W. Geng, D.P. Wang, X.H. Gan, J. Agric. Food Chem. 72 (2024) 12425-12433. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c09350 |

| [64] |

C. Zagar, R. Liebl, G. Theodoridis, M. Witschel, Protoporphyrinogen Ⅸ oxidase inhibitors, in: P. Jeschke, M. Witschel, W. Krämer, U. Schirmer (Eds.), Modern Crop Protection Compounds, 1st ed., Wiley, 2019, pp. 173–211.

|

| [65] |

H.Z. Yang, X. Wang, F.Z. Hu, X.F. Yang, Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 23 (2002) 2261-2263. |

| [66] |

F.Z. Hu, Z.G.F. Zhang, Y.Q. Zhu, et al., Chin. J. Org. Chem. 27 (2007) 758-762. |

| [67] |

F.Z. Hu, G.F. Zhang, B. Liu, et al., J. Heterocycl. Chem. 46 (2009) 584-590. DOI:10.1002/jhet.120 |

| [68] |

R.B. Zhang, S.Y. Yu, L. Liang, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 68 (2020) 13672-13684. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c05955 |

| [69] |

B.F. Zheng, Y. Zuo, W.Y. Yang, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 72 (2024) 10772-10780. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c09157 |

| [70] |

D.M. Barber, J. Agric. Food Chem. 70 (2022) 11075-11090. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c07910 |

| [71] |

M. Shino, T. Hamada, Y. Shigematsu, et al., Chapter 30-Discovery and mode of action of cyclopyrimorate: a new paddy rice herbicide, in: P. Maienfisch, S. Mangelinckx (Eds.), Recent Highlights in the Discovery and Optimization of Crop Protection Products, Academic Press, 2021, pp. 451–457.

|

| [72] |

M. Shino, T. Hamada, Y. Shigematsu, K. Hirase, S. Banba, J. Pestic. Sci. 43 (2018) 233-239. DOI:10.1584/jpestics.d18-008 |

| [73] |

M. Shino, T. Hamada, Y. Shigematsu, S. Banba, Pest Manag. Sci. 76 (2020) 3389-3394. DOI:10.1002/ps.5698 |

| [74] |

Y.X. Liu, D.G. Wei, Y.R. Zhu, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 56 (2008) 204-212. DOI:10.1021/jf072851x |

| [75] |

H.J. Kim, A.B. Bo, J.D. Kim, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 68 (2020) 15373-15380. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c01974 |

| [76] |

K.C. Salamanez, A.M. Baltazar, E.B. Rodriguez, et al., Philipp. J. Crop Sci. 40 (2015) 23-32. |

| [77] |

H.J. Ikeda, S. Ito, Y. Okada, et al., Sumitomo Kagaku (R&D Report) 2011-Ⅱ. (2025).

|

| [78] |

Y.X. Li, Y.P. Luo, Z. Xi, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 54 (2006) 9135-9139. DOI:10.1021/jf061976j |

| [79] |

M. Muehlebach, M. Boeger, F. Cederbaum, et al., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 17 (2009) 4241-4256. |

| [80] |

T.C. Sparks, Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 107 (2013) 8-17. |

| [81] |

W. Shi, X.H. Qian, R. Zhang, G.H. Song, J. Agric. Food Chem. 49 (2001) 124-130. |

| [82] |

S. Cao, X.H. Qian, G.H. Song, B. Chai, Z.S. Jiang, J. Agric. Food Chem. 51 (2003) 152-155. |

| [83] |

S. Cao, N. Wei, C.M. Zhao, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 53 (2005) 3120-3125. DOI:10.1021/jf047985e |

| [84] |

Q.C. Huang, X.H. Qian, G.H. Song, S. Cao, Pest Manag. Sci. 59 (2003) 933-939. |

| [85] |

M.M. Dang, M.H. Liu, L. Huang, et al., J. Heterocycl. Chem. 57 (2020) 4088-4098. DOI:10.1002/jhet.4118 |

| [86] |

S. Cao, D.L. Lu, C.M. Zhao, et al., Monatsh. Chem. 137 (2006) 779-784. DOI:10.1007/s00706-005-0476-7 |

| [87] |

R.F. Sun, Y.L. Zhang, F.C. Bi, Q.M. Wang, J. Agric. Food Chem. 57 (2009) 6356-6361. DOI:10.1021/jf900882c |

| [88] |

A.M. Buysse, M.C. Yap, R. Hunter, J. Babcock, X. Huang, Pest Manag. Sci. 73 (2017) 782-795. DOI:10.1002/ps.4465 |

| [89] |

K. Narusuye, T. Nakao, R. Abe, et al., Insect Mol. Biol. 16 (2007) 723-733. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2583.2007.00766.x |

| [90] |

M.M. Rahman, Y. Akiyoshi, S. Furutani, et al., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20 (2012) 5957-5964. |

| [91] |

M.M. Rahman, G.Y. Liu, K. Furuta, F. Ozoe, Y. Ozoe, J. Pestic. Sci. 39 (2014) 133-143. |

| [92] |

G.Y. Liu, Y. Wu, Y. Gao, X.L. Ju, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 68 (2020) 4760-4768. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.9b08189 |

| [93] |

G.Y. Liu, C.W. Zhou, Z.S. Zhang, et al., Pest Manag. Sci. 78 (2022) 2872-2882. DOI:10.1002/ps.6911 |

| [94] |

M.J. Chen, Z. Li, X.S. Shao, P. Maienfisch, J. Agric. Food Chem. 70 (2022) 11109-11122. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.2c00636 |

| [95] |

J. Shang, W.Y. Dong, H.B. Fang, et al., Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 197 (2023) 105694. |

| [96] |

C. Spalthoff, V.L. Salgado, N. Balu, et al., Pest Manag. Sci. 79 (2023) 1635-1649. DOI:10.1002/ps.7352 |

| [97] |

S.K. Ramadan, D.R. Abdel Haleem, H.S.M. Abd-Rabboh, et al., RSC Adv. 12 (2022) 13628-13638. DOI:10.1039/d2ra02388a |

| [98] |

R.N. Strange, P.R. Scott, Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43 (2005) 83-116. DOI:10.1146/annurev.phyto.43.113004.133839 |

| [99] |

M.C. Fisher, D.A. Henk, C.J. Briggs, et al., Nature 484 (2012) 186-194. DOI:10.1038/nature10947 |

| [100] |

X.J. Zou, G.Y. Jin, Chin. Chem. Lett. 12 (2001) 419-420. |

| [101] |

X.J. Zou, G.Y. Jin, Z.X. Zhang, J. Agric. Food Chem. 50 (2002) 1451-1454. |

| [102] |

X.J. Zou, L.H. Lai, G.Y. Jin, Z.X. Zhang, J. Agric. Food Chem. 50 (2002) 3757-3760. |

| [103] |

J. Wu, B.A. Song, H.J. Chen, P. Bhadury, D.Y. Hu, Molecules 14 (2009) 3676-3687. DOI:10.3390/molecules14093676 |

| [104] |

H. Morishita, A. Manabe, JP Patent 4747680, 2005.

|

| [105] |

Y. Matsuzaki, M. Kurahashi, S. Watanabe, et al., Pest Manag. Sci. (2024). DOI:10.1002/ps.8239 |

| [106] |

Y. Matsuzaki, S. Watanabe, T. Harada, F. Iwahashi, Pest Manag. Sci. 76 (2020) 1393-1401. DOI:10.1002/ps.5652 |

| [107] |

A. Manabe, H. Ikegami, H. Morishita, Y. Matsuzaki, Bioorg. Med. Chem. 88 (2023) 117332. |

| [108] |

H. Morishita, A. Manabe, PCT, WO 200121104, 2005.

|

| [109] |

C. Lamberth, S. Trah, S. Wendeborn, et al., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20 (2012) 2803-2810. |

| [110] |

F. Miao, X.J. Yang, L. Zhou, et al., Nat. Prod. Res. 25 (2011) 863-875. DOI:10.1080/14786419.2010.482055 |

| [111] |

X.J. Yang, F. Miao, Y. Yao, et al., Molecules 17 (2012) 13026-13035. DOI:10.3390/molecules171113026 |

| [112] |

Z.M. Cui, B.H. Zhou, C. Fu, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 68 (2020) 15418-15427. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06507 |

| [113] |

E.S. Moghadam, F. Bonyasi, B. Bayati, M.S. Moghadam, M. Amini, J. Agric. Food Chem. 72 (2024) 15427-15448. |

| [114] |

Y.N. Hao, M. Yu, K.H. Wang, et al., Pest Manag. Sci. 78 (2022) 982-990. DOI:10.1002/ps.6709 |

| [115] |

Z. Rozmer, P. Perjési, Phytochem. Rev. 15 (2016) 87-120. DOI:10.1007/s11101-014-9387-8 |

| [116] |

S. Chen, M.H. Zhang, S. Feng, et al., Arab. J. Chem. 16 (2023) 104852. DOI:10.1016/j.arabjc.2023.104852 |

| [117] |

M.Y. Hamed, A.F. Aly, N.H. Abdullah, M.F. Ismail, Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 43 (2023) 2356-2375. DOI:10.1080/10406638.2022.2044865 |

| [118] |

S.A. Rizk, A.Y. Alzahrani, A.M. Abdo, Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 44 (2024) 2991-3008. DOI:10.1080/10406638.2023.2227316 |

| [119] |

L.L. Fan, Z.F. Luo, Y. Li, et al., Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 30 (2020) 127139. |

| [120] |

S.G. Tiratsuyan, A.A. Hovhannisyan, A.V. Karapetyan, T.A. Gomktsyan, A.P. Yengoyan, Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 63 (2016) 656-662. |

| [121] |

R.S. Shainova, T.A. Gomktsyan, A.V. Karapetyan, A.P. Yengoyan, J. Chem. Res. 41 (2017) 205-209. |

| [122] |

R.S. Shainova, T.A. Gomktsyan, A.V. Karapetyan, A.P. Yengoyan, J. Chem. Res. 43 (2019) 352-358. DOI:10.1177/1747519819866402 |

| [123] |

T.A. Gomktsyan, R.S. Shainova, A.V. Karapetyan, A.P. Yengoyan, Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 91 (2021) 2019-2024. DOI:10.1134/s1070363221100145 |

| [124] |

T.A. Gomktsyan, R.S. Shainova, A.V. Karapetyan, et al., Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 92 (2022) 2492-2499. DOI:10.1134/s1070363222110354 |

| [125] |

A.P. Yengoyan, R.S. Shainova, T.A. Gomktsyan, A.V. Karapetyan, J. Chem. Res. 42 (2018) 535-539. DOI:10.3184/174751918x15389922302823 |

| [126] |

R.S. Shainova, T.A. Gomktsyan, A.V. Karapetyan, A.P. Yengoyan, J. Chem. Res. 44 (2019) 271-276. |

| [127] |

J.M. Jin, T.W. Shen, L.Z. Shu, et al., J. Agric. Food Chem. 71 (2023) 1291-1309. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.2c07315 |

| [128] |

L. Xing, Y.S. An, Y. Qin, et al., New J. Chem. 48 (2024) 117-130. DOI:10.1039/d3nj04902g |

| [129] |

C.L. Cantrell, F.E. Dayan, S.O. Duke, J. Nat. Prod. 75 (2012) 1231-1242. DOI:10.1021/np300024u |

| [130] |

K. Wang, L.H. Guo, Y.S. Zou, Y. Li, J.B. Wu, J. Antibiot. 60 (2007) 325-327. DOI:10.1038/ja.2007.42 |

| [131] |

C.F. Zhang, Q. Wang, M. Zhang, J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 11 (2009) 339-344. DOI:10.1080/10286020902771403 |

| [132] |

Y.M. Liu, J.S. Yang, Q.H. Liu, Chem. Pharm. Bull. 52 (2004) 454-455. |

| [133] |

L.M. Blair, J. Sperry, J. Nat. Prod. 76 (2013) 794-812. DOI:10.1021/np400124n |

| [134] |

Z. Ali, D. Ferreira, P. Carvalho, M.A. Avery, I.A. Khan, J. Nat. Prod. 71 (2008) 1111-1112. DOI:10.1021/np800172x |

| [135] |

A.M. Elissawy, S.S. Ebada, M.L. Ashour, Phytochem. Lett. 29 (2019) 1-5. |

2025, Vol. 36

2025, Vol. 36