b Natural Product Research Center, Chengdu Institute of Biology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Chengdu 610041, China;

c University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

The incorporation of fluorine or fluorine-containing motifs into amino acids established a completely new class of amino acids, fluorinated amino acids (FAAs) [1,2]. Compared to those non-fluorinated amino acids, their unique properties provided widespread bio-organic and medical applications, that exhibited as biological tracers, mechanistic probes and enzyme inhibitors, or used for blood pressure control, treatment of allergies, and tumour growth, etc. (Scheme 1A, selected FAA drugs) [3–7]. Besides, incorporation of FAAs constituted an important branch of peptide and protein science [8–10]. Therefore, with the growing demand of FAAs in life science, continuous efforts have been devoted to their structural diversity synthesis, and impressive progresses have been reached in recent years [11–13]. Notably, among these strategies, asymmetric functionalization of pro-chiral amino acid precursors by using available fluorinated reagents via C—C bond formation presented an efficient and direct strategy to access chiral FAAs [14,15].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. (A) Selected FAAs drugs and difluoromethyl bioactive compounds. (B) Direct difluoromethylation using difluoromethyl reagents. (C) Asymmetric difluorobenzylation via [ArCF2+]. | |

As an important component of FAAs, gem–difluorinated amino acids (DFAAs) that containing difluoromethylene group (CF2R), gain increasing interests in recent years, due to the ability of CF2R group to serve as hydrogen bond donor (CF2H) or metabolic biologically stable bioisostere of ethereal oxygens (CF2R), and presented intriguing chemical structures and promising diverse biological activities (Scheme 1A, selected difluorinated molecules) [16–18]. To date, various difluoromethyl fragments (CF2R, R = H, alkyl, alkenyl, alkynyl, ester, amide) could be introduced through a C—C bond formation approach from readily available difluoromethyl reagents [19–31]. These transformations always involved a difluorocarbene intermediate or entailed a radical pathway, which limit broader utility in asymmetric synthesis [27], especially difluorinated amino acids synthesis (Scheme 1B) [19]. Till very recently, Guo et al. firstly disclosed the asymmetric difluoromethylation through a key difluorocarbene specie and provided a direct and efficient synthesis of chiral DFAAs with excellent results [32]. From the respect of the significance of DFAAs in bioactive molecules discover, searching suitable difluoromethyl reagents to tailor a novel pathway seems attractive to conquer the long-standing challenges in preparing structure diverse chiral DFAAs.

α,α-Difluorinated benzyltriflones (ArCF2SO2CF3), easily prepared with efficient activator for fluorination and good leaving group, were exhibited as elegant difluoromethyl reagent in desulfonylative cross-coupling reactions [33,34]. In these cases, α-difluorinated arylmethanes ArCF2X (X = Ar, 18F, Cl, Br, I, O, S) were obtained through [ArCF2Pd] [33] or [ArCF2+] [34] intermediates, which were different from those traditional difluoromethyl reagents that need to undergo carbene intermediates or radical pathway. These results provided us opportunities to realize the asymmetric difluorobenzylation from α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflones and further extend the diversity of chiral α-difluorinated compounds, which has never been achieved.

Asymmetric α-C-alkylation of stabilized prochiral enolates from α-imino esters and chiral catalysts presented the most fundamental and important approach for the construction of ubiquitous quaternary α-amino acids [35–44]. Various alkyl reagents were employed via this strategy, where the produced α-amino acid derivatives always provided conspicuous bioactivities. In particular, compared to these non-fluorinated counterparts, rare studies were focused on the α-C-fluoroalkylation [32,43], especially difluoroalkylation, which furnished DFAAs and still remained blank. We envisioned that in the presence of prochiral enolate, α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflones (ArCF2SO2CF3) as difluoromethyl reagents could be introduced to generate a carbocation intermediate [34] and consequently underwent a nucleophilic substitution, as a result, chiral α-quaternary difluorobenzylated amino acids (DFAAs) could be afforded (Scheme 1C). Herein, by using α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflones (ArCF2SO2CF3) as difluoromethyl reagents, we reported the first Cu-catalyzed enantioselective difluorobenzylation of aldimine esters. Structurally diverse DFAAs were achieved under mild conditions with excellent enantio–control. In addition, polyfluoroarenes were also found efficient candidates, provided polyfluoroaryl amino acids as desired products in good results. Gram-scale experiment, late- stage functionalization and useful product transformations were carried out to reveal the utility of this protocol, which largely enriched the structural diversity of FAAs and provided potential opportunities in drug discovery.

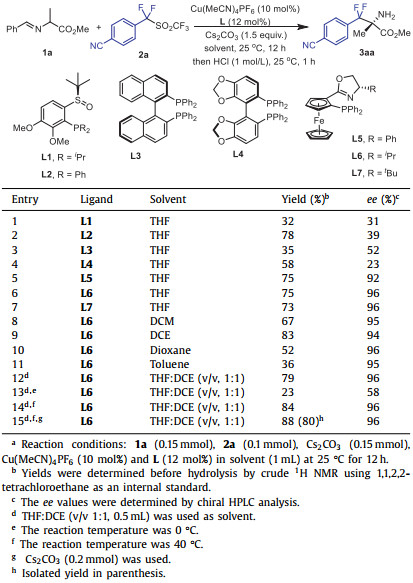

We started our initial study by selecting imino ester 1a and α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflone 2a as model substrates (Table 1, for details, see Supporting information). First, chiral ligands were evaluated. By using SOPs (chiral sulfoxide phosphine [45–49])/Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (1:1.2, 10 mol%) as chiral catalyst, the desired DFAA derivative 3aa was smoothly delivered, but unsatisfied enantio–control was obtained (entries 1 and 2, 31%−39% ee). Subsequently, selected commercially available chiral ligands were carefully screened. Biaryl-type ligands, such as (R)-BINAP (L3), (R)-SEGPHOS (L4), provided poor results (entries 3 and 4). To our delight, chiral ligands with ferrocene skeleton flourished excellent enantioselectivities and good yields, in which the substituents on the oxazole ring had little effect on reactivity and enantio–control (entries 5–7, 73%−75% yields, 92%−96% ee). Next, various solvents were evaluated (entries 8–11). All the cases provided excellent enantioselectivities, while yields varied (36%−83% yields, 94%−96% ee). Mixed solvent THF/DCE (v/v, 1:1) was optimal in the terms of both yield and enantio–control (entry 12). Besides, this asymmetric difluorobenzylation was found very sensitive to the reaction temperature. The reaction was obviously suppressed when carried out at 0 ℃ (entry 13, 23% yield, 58% ee). Furthermore, a slight increase of yield was obtained when the reaction was conducted with 2.0 equiv. base at 40 ℃ (entries 14 and 15). Therefore, after systematic evaluation, we finally confirmed the optimal reaction conditions: Cu(MeCN)4PF6/L6 (1:1.2, 10 mol%), Cs2CO3 (2.0 equiv.) in THF/DCE (v/v, 1:1, 0.5 mL) at 40 ℃ for 12 h (Table 1, entry 15, 80% isolated yield, 96% ee).

|

|

Table 1 Optimization of reaction conditions.a |

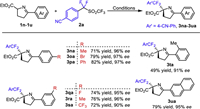

With the optimal conditions of this asymmetric difluorobenzylation in hand, the substrate scope was carefully examined, and the results were summarized in Scheme 2. For imino esters 1 (Scheme 2A), first, changing ester groups was found little effect on reactivity with identical enantioselectivity (3aa-3ca, 71%−82% yields, 96% ee). Imino esters derived from various natural amino acids, such as leucine (Leu), methionine (Met), aspartic acid (Asp), lysine (Lys), were tolerated under the conditions, desired DFAAs were obtained in acceptable yields and excellent enantioselectivities (3da-3ga, 91%−96% ee). Imino ester from glutamic acid (Glu) worked smoothly, followed an ammonolysis cyclization to provide cyclic DFAA 3ha, which was determined by X-ray analysis to confirm the absolute configuration as (R). Norleucine (NLeu) and homophenylalanine (HPhe) were competent with satisfied results (3ia-3ja, 94%−95% ee). Furthermore, imino esters containing CN, alkenyl and alkynyl group were also successful candidates under the conditions (3ka-3ma).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Asymmetric synthesis of difluorinated amino acids (DFAAs). Reaction conditions: 1 (0.15 mmol), 2 (0.1 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.2 mmol), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (10 mol%) and L6 (12 mol%) in THF: DCE (v/v 1:1, 0.5 mL) at 40 ℃ for 12 h. Isolated yields were provided. The ee values were determined by chiral HPLC analysis. a 1a (0.25 mol) was used. | |

For difluorinated benzyltriflones 2 (Scheme 2B), substituent NO2 could be installed on the p-, m- and o-position of aromatic ring, lower reactivity was detected in the case of o-substituted substrate (3aa vs. 3ae), which indicated the reaction was sensitive to steric effect from substrate 2 (3ab vs. 3ac-3ad). Next, various electron-withdrawing groups were introduced at p-position and found compatible to smoothly provide the corresponding DFAAs (3af-3ai). Disubstitued DFAAs (3aj-3al, 90%−93% ee) were readily produced with satisfactory enantio–control with reduced reactivity when o-position was occupied (3ak, 41% yield). Interestingly, when 3,4,5-trifluoro substituted 2m was employed, another unexpected C-F bond activation occurred with excellent results (3am, 78% yield, 99% ee, dr 14:1), thus two amino acids could be incorporated, provide potential utility in bio- and medical chemistry. Meanwhile, DFAA 3an with biologically active heterocycle quinine could be afforded (75% yield, 96% ee).

Besides, cyclic imino esters could also undergo the asymmetric difluorobenzylation reaction with α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflones 2a (Scheme 3, 3na-3ua, 90%−97% ee). Various substituents (such as Me, pH, F, Cl, Br, CF3) could be installed at the p- and m-position of the aromatic ring with no obvious electronic effect and steric effect. While, moderate yield was provided in the case of o-substituted cyclic imino ester was introduced (49% yield, 3ta vs. 3na and 3ra).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Asymmetric synthesis of difluorinated amino acid derivatives. Reaction conditions: 1a (0.15 mmol), 2a (0.1 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.15 mmol), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (10 mol%) and L6 (12 mol%) in THF: DCE (v/v, 1:1, 0.5 mL) at 20 ℃ for 12 h. Isolated yields were provided. The ee values were determined by chiral HPLC analysis. | |

Polyfluoroaryl amino acids, an important part of FAAs, could already been prepared by C-F bond activation of polyfluoroarenes [50,51]. While, their asymmetric synthesis remains unrealized. As mentioned above in Scheme 2 (3am), polyfluoroarene was competent electrophile via an unexpected C-F bond activation to produce corresponding chiral polyfluoroaryl amino acid. Encouraged by the results, we subsequently evaluated a series of polyfluoroarenes under the conditions (Scheme 4). To our delight, polyfluoroarenes with CN, NO2, COMe and benzoxazole were all tolerated, C-F bond activation exclusively occurred at the p-position with little effect on enantio–control (5aa-5ad, 94%−96% ee). Notably, when adjusting the amount of 1a to 2.5 equiv., two continuous C-F bond activations occurred in one pot with excellent diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivity (5ae). These results provided opportunities for the preparation of complex FAAs. In the cases of unsymmetric polyfluoroarenes, the C-F bond activation regioselectively occurred at the more electron-deficient position, which was consistent with the computational regioselectivity (5af, 5ag) (orbital-weighted Fukui index (OW-f+) was computed, see Supporting information for details) [49,52]. In addition, when 1h was employed, intramolecular cyclization to 5-membered lactam was achieved, and further determination by X-ray analysis confirmed the absolute configuration was (S)-configuration (5hd).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 4. Asymmetric synthesis of polyfluoroaryl amino acid derivatives. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.1 mmol), 4 (0.12 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.2 mmol), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (10 mol%) and L6 (12 mol%) in THF: DCE (v/v 1:1, 0.5 mL) at 20 ℃ for 12 h. Isolated yields were provided. The ee values were determined by chiral HPLC analysis. a 1a (0.25 mmol) and 4c (0.1 mmol) were used. b The reaction was carried out with Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (5 mol%) and L6 (6 mol%) at 0 ℃. | |

To demonstrated the utility of this protocol, difluorinated benzyltriflones 2a was scaled up to 6 mmol, the corresponding product 3aa was obtained with good results (1.13 g, 73% isolated yield, 96% ee) (Scheme 5A). Later, late-stage modifications of natural products were carried out. Using this protocol, difluorinated benzyltriflone 2o (derived from L-menthol) and polyfluoroarene 4h (derived from cholesterol) were all applicable with acceptable results (Scheme 5B). Further, under the standard conditions, imino ester 1v could be smoothly delivered to the corresponding DFAA 3va, an analogue of (R)-DFMO for treatment of African sleeping sickness [32,53,54], with excellent enantio–control (90% ee) (Scheme 5C). In addition, useful transformations of product 3aa were conducted. The incorporations of amino acids with DFAA 3aa provided the desired difluorinated dipeptides (6, 7) in moderate yields. When treating 3aa with aryl isocyanate, BIRT-377 [55,56] analogue 8 could be obtained under mild conditions, which might provide potential bio-activity compared to the non-fluorinated counterparts (Scheme 5D).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 5. Scale-up experiment and synthetic utility. | |

Classical difluoromethylation from difluoromethyl reagents always involved a difluorocarbene intermediate or entailed a radical pathway [19]. First, radical trapping reagent TEMPO (5.0 equiv.) was added, the desired DFAA 3aa still formed while in much less yield (probably due to the oxidation of Cu(I) that destroy the catalyst by TEMPO), and no radical product was detected. This indicates the catalytic system did not promote the reaction via a radical pathway, which is different from those traditional difluoromethylation reactions (Scheme 6A) [19]. Thus, control experiments and desorption electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (DESI-MS) [57,58] were performed to gain the mechanistic insight (for details see Supporting information). First, α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflone with electron-donating group (2p) was introduced as difluorobenzyl reagent, no corresponding product was obtained and 2p (99%) recovered (Scheme 6B). When 2a and 2d (with similar Hammett constant: NO2 (σ = 0.78), CN (σ = 0.66)) [59] in a 1:1 ratio were used as substrates under standard conditions, products 3aa and 3ad were obtained in 25.7% and 58.4% yield, respectively. While in the case of 2d and 2f (with gaps in electronegativity: NO2 (σ = 0.78), COPh (σ = 0.43)), the less electron-withdrawing group substituted difluorobenzyl reagent (2f) was suppressed with no desired product was detected (Scheme 6C). These results obviously suggested that (a) the electronegativity of substituents from difluorobenzyl reagents 2 plays a crucial role for the reaction; (b) difluorinated benzyltriflone with electron-donating group (2p) were not suitable electrophile, probably due to the detrimental effect for difluorinated reagent polarization and sulfonyl group leaving, that lead difluorinated benzyltriflone recovered; (c) electron-deficient substituent in the electrophiles might facilitate the reaction and their electronegativity showed significant positive correlation with the reaction rate.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 6. (A) Radical trapping experiment. (B) Control experiment. (C) Competing experiments. (D) Proposed transition state. | |

To further confirm the key intermediate involved in the reaction, DESI-MS analysis was employed (Fig. S7 in Supporting information). Generally, the C(benzylic)-sulfonyl bond is easily cleaved to generate benzylic cation. The desired difluorocarbocation intermediate (2j, calcd. for C9H6BrF2O2+ 262.9514, Found: 262.9514) was detected when α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflone (2j) was introduced in the presence or absence of the catalytic system. Thus, based on these experimental results and previous work [34], a possible transition state was proposed to elucidate the enantio–control. The in-situ formed difluorocarbocation was captured by pro-chiral enolate, which was generated from α-imino esters 1a and chiral catalyst by base. Due to the steric hindrance between the aryl group (from difluoromethyl reagent) and isopropyl group (from chiral ligand), the Re-face was shielded, difluorocarbocation 2j approached to 1a from its Si-face to provide the desired product (R)−3aj with good results (Scheme 6D).

In summary, we have developed the first Cu-catalyzed difluorobenzylation of aldimine esters with α,α-difluorinated benzyltriflones as difluoromethyl reagents. This protocol opened us a straightforward access to various DFAAs with α-quaternary center in wide scope, good yields and excellent enantioselectivities (90%−98% ee). Control experiments and DESI-MS analysis revealed that the reaction probably proceed via a curial difluorocarbocation intermediate (ArCF2+). Moreover, polyfluoroarenes were also found competent electrophiles to provide the corresponding polyfluoroaryl amino acids with good results. Besides, gram-scale experiment, late-stage modifications of natural products and efficient synthesis of difluorinated dipeptides and bio-active molecule analogues by product derivations were conducted with good efficiency. These results largely enriched the structural diversity of FAAs and provided more potential opportunities in drug discovery.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported financially by the Youth Innovation Promotion Association CAS (No. 2022375), National Nature Science Foundation of China (No. 22171258), the Biological Resources Programme, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. KFJ-BRP-008) and the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (No. 2022ZYD0038).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.109665.

| [1] |

I. Ojima, Fluorine in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

|

| [2] |

X.L. Qiu, F.L. Qing, Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011 (2011) 3261-3278. DOI:10.1002/ejoc.201100032 |

| [3] |

P. Jeschke, ChemBioChem 5 (2004) 570. DOI:10.1002/cbic.200300833 |

| [4] |

K.L. Kirk, J. Fluorine Chem. 127 (2006) 1013. DOI:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2006.06.007 |

| [5] |

S. Purser, P. Moore, S. Swallow, V. Gouverneur, Chem. Soc. Rev. 37 (2008) 320-330. DOI:10.1039/B610213C |

| [6] |

W.K. Hagmann, J. Med. Chem. 51 (2008) 4359-4369. DOI:10.1021/jm800219f |

| [7] |

E.P. Gillis, K.J. Eastman, M.D. Hill, D.J. Donnelly, N.A. Meanwell, J. Med. Chem. 58 (2015) 8315-8359. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00258 |

| [8] |

M. Salwiczek, E.K. Nyakatura, U.I. Gerling, S. Ye, B. Koksch, Chem. Soc. Rev. 41 (2012) 2135-2171. DOI:10.1039/C1CS15241F |

| [9] |

E.N.G. Marsh, Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 2878-2886. DOI:10.1021/ar500125m |

| [10] |

J.N. Sloand, M.A. Miller, S.H. Medina, Pept. Sci. 113 (2021) e24184. DOI:10.1002/pep2.24184 |

| [11] |

J. Moschner, V. Stulberg, R. Fernandes, et al., Chem. Rev. 119 (2019) 10718-10801. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00024 |

| [12] |

X.X. Zhang, Y. Gao, X.S. Hu, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 362 (2020) 4763-4793. DOI:10.1002/adsc.202000966 |

| [13] |

M.Q. Zhou, Z. Feng, X.G. Zhang, Chem. Commun. 59 (2023) 1434-1448. DOI:10.1039/D2CC06787K |

| [14] |

X. Xu, L.Z. Bao, L. Ran, et al., Chem. Sci. 13 (2022) 1398. DOI:10.1039/D1SC04595D |

| [15] |

H.Y. Wang, J. Li, L.Z. Peng, J. Song, C. Guo, Org. Lett. 24 (2022) 7828. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c03175 |

| [16] |

Y. Zafrani, G. Sod-Moriah, D. Yeffet, et al., J. Med. Chem. 62 (2019) 5628-5637. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b00604 |

| [17] |

M. Shevchuk, Q. Wang, R. Pajkert, J.C. Xu, H.B. Mei, Adv. Synth. Catal. 363 (2021) 2912-2968. DOI:10.1002/adsc.202001464 |

| [18] |

Y. Zafrani, S. Saphier, E. Gershonov, Fut. Med. Chem. 12 (2020) 361-365. DOI:10.4155/fmc-2019-0309 |

| [19] |

A.D. Dilman, V.V. Levin, Acc. Chem. Res. 51 (2018) 1272-1280. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.8b00079 |

| [20] |

F.L. Qing, X.Y. Liu, J.A. Ma, et al., CCS Chem. 4 (2022) 2518-2549. DOI:10.31635/ccschem.022.202201935 |

| [21] |

C. Matheis, K. Jouvin, L.J. Goossen, Org. Lett. 16 (2014) 5984-5987. DOI:10.1021/ol5030037 |

| [22] |

Z. Feng, Q.Q. Min, H.Y. Zhao, J.W. Gu, X.G. Zhang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 1270-1274. DOI:10.1002/anie.201409617 |

| [23] |

J.W. Gu, X.G. Zhang, Org. Lett. 17 (2015) 5384-5387. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02739 |

| [24] |

Z.C. Lu, O. Hennis, J. Gentry, B. Xu, G.B. Hammond, Org. Lett. 22 (2020) 4383-4388. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01395 |

| [25] |

K. Choi, M.G. Mormino, E.D. Kalkman, J. Park, J.F. Hartwig, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202208204. DOI:10.1002/anie.202208204 |

| [26] |

X. Zeng, Y. Li, Q.Q. Min, X.S. Xue, X.G. Zhang, Nat. Chem. 15 (2023) 1064-1073. DOI:10.1038/s41557-023-01236-8 |

| [27] |

N. Rao, Y.Z. Li, Y.C. Luo, Y.X. Zhang, X.G. Zhang, ACS Catal. 13 (2023) 4111-4119. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c06149 |

| [28] |

R.I. Rodríguez, M. Sicignano, J. Alemán, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e20211263. |

| [29] |

X.L. Zhu, Y. Huang, X.H. Xu, F.L. Qing, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 817-820. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.07.030 |

| [30] |

Z.W. Chen, H.Y. Sheng, X. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108937. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108937 |

| [31] |

W.J. Yuan, C.L. Tong, X.H. Xu, F.L. Qing, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 23899-23904. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c08858 |

| [32] |

L.Z. Peng, H.Y. Wang, C. Guo, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 6376-6381. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c02697 |

| [33] |

M. Nambo, J.C.H. Yim, L.B.O. Freitas, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4528. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-11758-w |

| [34] |

R.X. Yang, X.Y. Gao, K.H. Gong, et al., Org. Lett. 24 (2022) 164-168. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c03803 |

| [35] |

Z.Y. Xue, Q.H. Li, H.Y. Tao, C.J. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133 (2011) 11757-11765. DOI:10.1021/ja2043563 |

| [36] |

L. Wei, X. Chang, C.J. Wang, Acc. Chem. Res. 53 (2020) 1084-1100. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.0c00113 |

| [37] |

L. Wei, C.J. Wang, Chin. J. Chem. 39 (2021) 15-24. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.202000380 |

| [38] |

T.B. Wright, P.A. Evans, Chem. Rev. 121 (2021) 9196. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00564 |

| [39] |

L. Peng, Z. He, X. Xu, C. Guo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 14270-14274. DOI:10.1002/anie.202005019 |

| [40] |

J.Z. Xiao, H.B. Xu, X.H. Huo, W.B. Zhang, S.M. Ma, Chin. J. Chem. 39 (2021) 1958-1964. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.202100002 |

| [41] |

Y.B. Peng, C.Y. Han, Y.C. Luo, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202203448. DOI:10.1002/anie.202203448 |

| [42] |

Z.C. Liu, Z.Q. Wang, X. Zhang, L. Yin, Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 2187. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-37967-y |

| [43] |

Y.C. Luo, Y.Q. Ma, G.L. Li, X.H. Huo, W.B. Zhang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. (2023) e2023138388. |

| [44] |

Y.N. Li, X. Chang, Q. Xiong, X.Q. Dong, C.J. Wang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 4029-4032. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.05.063 |

| [45] |

T. Jia, M. Wang, J. Liao, Top. Curr. Chem. 377 (2019) 8. DOI:10.1007/s41061-019-0232-9 |

| [46] |

Y. Liao, X.M. Yin, X.H. Wang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 1176-1180. DOI:10.1002/anie.201912703 |

| [47] |

J.L. Ye, Y. Liao, H. Huang, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 3032. DOI:10.1039/D0SC05425A |

| [48] |

J. Han, B. Xiao, T.Y. Sun, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2022) 21800-21807. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c10559 |

| [49] |

H.X. Lin, X. Huang, W. Jiao, et al., Org. Lett. 25 (2023) 3239-3244. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.3c00948 |

| [50] |

K.A. Teegardin, J.D. Weaver, Chem. Commun. 53 (2017) 4771. DOI:10.1039/C7CC01606A |

| [51] |

X.W. Tao, L.N. Yi, M.Y. Huang, Y. Fu, Q. Yang, J. Org. Chem. 87 (2022) 14476. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.2c01906 |

| [52] |

W.G. Xu, Q. Shao, C.J. Xia, et al., Chem. Sci. 14 (2023) 916. DOI:10.1039/D2SC06290A |

| [53] |

N. Qu, N.A. Ignatenko, P. Yamauchi, et al., Biochem. J. 375 (2003) 465. DOI:10.1042/bj20030382 |

| [54] |

R.T. Jacobs, B. Nare, M.A. Phillips, Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 11 (2011) 1255. DOI:10.2174/156802611795429167 |

| [55] |

T.A. Kelly, D.D. Jeanfavre, D.W. McNeil, et al., J. Immunol. 163 (1999) 5173. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.163.10.5173 |

| [56] |

N.S. Chowdari, C.F. Barbas, Org. Lett. 7 (2005) 867. DOI:10.1021/ol047368b |

| [57] |

A. Kumar, S. Mondal, S. Banerjee, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 2459. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c12512 |

| [58] |

A. Kumar, S. Mondal, Sandeep, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2022) 3347. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c12644 |

| [59] |

Corwin. Hansch, A. Leo, R.W. Taft, Chem. Rev. 91 (1991) 165-195. DOI:10.1021/cr00002a004 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35