b Canadian Light Source, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada;

c Department of Physics, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK S7N 5B2, Canada

Energy conversion and storage technologies which consume or produce hydrogen sparkle in addressing fossil fuels related issues, with the virtue of high energy density and emission free [1–4]. Electrochemical water splitting, as a paramount hydrogen production technology, is a thriving strategy yet faces grand obstacle which requires noble metal as the anodic electrocatalyst to overcome the sluggish kinetics for oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [5–8]. Tremendous endeavor has been devoted to explore affordable and robust substitution for precise metal electrocatalyst, and the so-called M-N-C single atom catalysts (M: transition metal, SACs) have attracted enormous interest which not only deliver comparable reaction activity as commercial catalysts but also demonstrate advantage in alleviating market cost for large scale application [9–19].

Additional benefit of M-N-C SACs includes the explicit active site configuration, i.e., metal singlet coordinated with four nitrogen atoms (MN4 motif), an ideal model to rationalize reaction mechanism. Efforts to further improve the catalytic performance is thus achievable via alternating central metal and its coordinators, which, in return, demonstrates a structure-properties relationship to guide catalytic design. However, the mono-atomic structure suffers from some limitations [18–23]. For example, it is of grand challenge for the singlet active center to break the linear scaling relationships between the adsorption energies of reaction intermediates, which would jeopardize the multi-intermediate involved reactions from climbing to the limiting-potential (UL) apex [19]. In the process of OER which involves 4e steps and various reaction intermediates, obvious change of different key oxygen containing reaction intermediates poses severe overpotential (η), causing inferior catalytic activity [24]. A promising strategy to overcome this dilemma is to introduce a second transition metal, forming dual metal site catalysts (DMSCs) [25–30]. A typical example in M-N-C family is the cooperation of Fe/Co [25], and following the pioneer work, a combination of Fe/Ni had been proposed as promising OER catalyst [26], whereby the conductivity is greatly improved compared with that of its SAC counterparts. Moreover, bifunctional catalytic performance for both oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) and OER can be derived with OH self-binding on the Fe/Ni-N-C surface, which demonstrates great aptitude to realize the excellent catalytic performance [27].

Transition metal combinations are the mainstream selections for available DACs, including Fe/Co, Fe/Cu, Fe/Zn, Zn/Co, etc. [25–30]. In comparison, main group metals with s/p block are mostly applied for thermocatalysis, yet only a few of them have been applied in electrocatalysis [31–33]. It is aware that main group metals usually have fewer valence electrons which endows them advantages to effectively avoid side reactions, adding thriving opportunities in engineering versatile SACs. In a recent study of Mg-N-C [31], strong adsorption of *OH is revealed in the catalytic activity volcano plot, despite coordination engineering can alleviate the interaction to some extent. Appealingly, the formation of *OH from water molecular is the first step for OER and an intense binding can trigger facile cracking of H2O. On the other hand, to avoid strong binding of *OOH (the last key intermediate to generate O2 by donating the proton), a cooperation with an adjacent transition metal is proposed whereby both metals can be active sites, rendering smooth releasing of O2.

Herein, a range of dual metal sites MIMII-N-C, MI from main group elements and MII from forth period transition elements, have been screened via density functional theory (DFT) calculations. It is found that the p-d coupling is able to improve the binding strength of *O relative to that of *OH and *OOH intermediates and minimizing theoretical overpotential. Based on this line, the Mg-Co couple is predicted to be promising for OER catalyst. Moreover, the Mg/Co-N-C is able to maintain a stable current density at around 10 mA/cm2 for 10 h consecutive operation, in well accordance with the theoretical simulation. The durability and degradation mechanism has also been examined in harsh environment. It is revealed that although the reaction center can be maintained in acidic medium, the strong binding of *OH intermediate hampered the formation of *O, limiting the reaction activity. On the contrary, not only the reaction moiety can stand up the oxidation by OH− in alkaline condition, but also the reaction activity can achieve to the theoretical limitation (0.37 V), underlining its robustness for alkaline overall water splitting.

The reaction activity of Mg singlet has been firstly considered in a typical OER procedure (Fig. 1a). Six models of MgNx (x = 1–4) involving possible configurations of N and C as coordinators are simulated yet MgN1 is unstable with positive formation energy. For the other five motifs, it is revealed that the potential determining step (PDS) is the *OH → *O procedure and due to large free energy change of this step, which gives rise to a large overpotential of 1.50 V for MgN4 reaction center. Although a smaller overpotential of 0.77 V can be achieved in MgN2 (III) (Fig. S1 in Supporting information), it is far from the satisfactory of commercial. To better understand the interaction of the catalytic surface and the adsorbates, partial density of states for the O 2p, Mg 3s/3p has been evaluated. It is seen that the O 2p orbitals can well hybrid with Mg 3s/3p orbitals in *OH intermediate (Fig. 1b), producing a stable O 2p6 full-occupied state (Fig. 1c) and generating a lower level of the *OH step in the free energy diagram. However, in the *O species, finite O 2p orbitals are populated above the Fermi level (EF), forming electron-deficient state which lifts the *O step in energy. As a result, severe overpotential is induced by the large energy change for *OH → *O.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Theoretical calculations. (a) The key reaction intermediates in the main elementary steps. (b) The density of states for *OH and *O. (c) Schematic illustration of the interaction between O 2p and Mg 3s/3p orbitals. The reaction volcano plot relative to (d) the change of ΔG*O-ΔG*OH and (e) both ΔG*O-ΔG*OH and ΔG*OH. (f) Summary of MgMII (MII = Fe, Co, Mn, Ni) and MICo (MI = Ca, Al, Sn). | |

Following the clue above, the introduction of transition metals is expected to tune the orbital interaction between oxygen and catalytic surface. As a prototype, Co was selected to form adjacent bimetal site with Mg, which featured with strong hybridization with O valence state [34]. As shown in the bottom of Fig. 1b, it is clear that the O 2p orbitals are resemble with that in its SAC counterpart in *OH intermediate, but it behaves distinctively in *O, which exhibits itinerant character when coupling with MgCoN6 fragment. Meanwhile, the shape of the density of states suggests intense interaction between O 2p and Co 3d, beneficial to stabilize the *O intermediate via virtual electron hopping. As a result, the free energy of *O is lowered and the overpotential is reduced to be 0.55 eV, smaller than that of Mg-N-C. To provide more confidence for experiments, 32 MgCoNx bimetal motifs with x = 1–6 along with MgMgN6 are built. Formation energy calculation rules out 16 of them (x = 1, 2 and part of x = 3, Fig. S2 in Supporting information). The data of free energy change for each step diagram is listed in Table S1 (Supporting information) and the corresponding intermediate configurations can be found in Fig. S3 (Supporting information). The derived reaction activity volcano plot is depicted in Fig. 1d. It is shown that, in contrast to the single reaction site (hollow square) which exhibits weak *O binding, the locations of the dual metal sites move leftwards, reducing the difference from ΔG*O to ∆G*OH, accompanied with the decreasing overpotential which climbs up to the vicinity of the volcano apex. As demonstrated in Fig. 1e, whereby the dark blue region indicates the theoretical minimum value for the overpotential (0.37 V), a favorable (ΔG*O - ΔG*OH) around 1.5 eV is required, corresponding to the volcano apex in Fig. 1d. It is found that, this p-d cooperation also work with other transition metals, i.e., Mn, Fe, Ni, but less effectively, while other main group metals, including Ca, Sn and Al, can not well couple with transition metals due to low energy level of their p orbitals Fig. 1f.

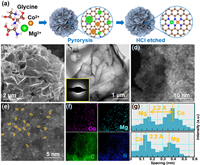

In light of the promising catalytic performance, Mg/Co-N-C catalyst was synthesized by a simple one-step wet chemical method (Fig. 2a), as referred from our previous studies [31]. The scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Fig. 2b) images of Mg/Co-N-C sample displayed the typical flower-like morphology. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) results exhibit an ultrathin sheet-like structure of petals (Fig. 2c), and no metal nanoparticles were found, which was consistent with in X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns (Fig. S4 in Supporting information). The high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM, Figs. 2d and e) and elemental mapping (Fig. 2f and Table S2 in Supporting information) images confirm the uniform distribution of Mg and Co components without any metallic aggregation. The atomic pairs are circled by yellow (Fig. 2e), and statistical analysis of 25 couples shows an average distance of atomic pairs of 2.2 Å, underlining an intimate interaction between metallic atoms (Fig. 2g). Moreover, the neighboring atoms show different contrasts, suggesting that the atomic pair is composed of two different elements. Further elemental analysis with inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) reveals that the loading contents of diatomic metals are 0.71 (Mg) and 1.67 (Co) wt%, respectively, and the corresponding atomic ratio is about 1:1 (Tables S3 and S4 in Supporting information).The Raman spectrum was also conducted to characterize carbon material defects and graphitization (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). The ratio of the D to G peak (ID/IG ≈ 0.913) is deduced, which underlines a large amount of defect site and low degree of graphitization [35–37]. Compared with its SAC counterparts, Mg/Co-N-C possesses the largest specific surface area (1237.64 m2/g), offering more active sites and ion diffusion channels (Figs. S6 and S7 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthetic strategy for Mg/Co-N-C. (b) SEM image. (c) TEM images. (d) HAADF-STEM and (e) the magnified images of Mg/Co-N-C. (f) EDS elemental mapping images. (g) The corresponding Z-contrast analysis in (e). | |

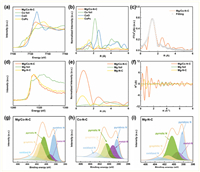

X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) and X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) were conducted to disclose the fine structure of local coordination environment of Mg/Co-N-C. As shown in the K-edge XANES spectrum of Co (Fig. 3a), the adsorption edge of Mg/Co-N-C is located between those of Co foil and CoO, indicating a mixed valence state between 0 and +2. It is also noticed that the threshold of the near-side absorption is similar as that of CoPc, demonstrating a similar coordination environment. The Fourier transform (FT) k3-weighted χ(k) function of the EXAFS spectrum (Fig. 3b) presents a predominant peak around 1.32 Å for Mg/Co-N-C, which is attributed to the first shell Co-N coordination scattering. The typical peak of Co-Co at 2.2 Å (say in Co foil) is absent but shifts to ~2.5 Å in Mg/Co-N-C, suggesting another type metal-metal interaction. The coordination from the subsequent least squares EXAFS fitting is ~4 (Fig. 3c and Table S5 in Supporting information), consistent with the theoretical model (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, the K-edge XANES spectrum of Mg is also similar for those of the Mg/Co-N-C to Mg-N-C and the small discrepancy is understandable in view of the possible charger-transfer for the bimetal site (Fig. 3d). Alike that of Co, the Fourier transform (FT) k3-weighted χ(k) function of the EXAFS spectrum (Fig. 3e) for the first shell interaction of Mg-coordination shifts a small amount for Mg/Co-N-C, compared with that of Mg-N-C, suggesting same kind but different intense bonding. Meanwhile the second peak is near but different from the Mg-Mg interaction in Mg foil, revealing a Mg-Co bonding. The K-space oscillation, via FT-from the energy space oscillation (Fig. 3f) with the R space data, provides a basis for fitting the bond length and the coordination number. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted to determine the surface distribution of elements and their valence states of the catalysts. The C 1s peak at 284.6 eV was used to calibrate the spectrum (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). Meanwhile, the peak at 285.9 eV assigned to the bonding of C—N, proves the formation of N-doped carbon [38]. In Figs. 3g-i, the high-resolution N 1s spectrum is measured. It is seen that five peaks of oxidized-N (402.9 eV), graphite-N (401.2 eV), pyrrolidine-N (400.5 eV), metal-N (399.4 eV) and pyridine-N (398.2 eV), revealing that the Mg/Co single atoms are coordinated with N atoms. The Mg 1s and Co 2p spectrum of all the samples cannot be assigned to the apparent peak due to the low content (Fig. S9 and Table S4 in Supporting information), consistent with previous reports [39–41].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Co K-edge XANES and (b) Fourier-transform EXAFS spectra. (c) Corresponding EXAFS fitting curves at the Co K-edge of Mg/Co-N-C. (d) Mg K-edge XANES and (e) Fourier-transform EXAFS spectra. (f) Mg K-edge EXAFS shown in k2-weighted k-space. N 1s XPS spectra of the (g) Mg/Co-N-C, (h) Co-N-C, and (i) Mg-N-C samples. | |

Electrochemical OER measurements are performed in a three-electrode configuration under 1 mol/L KOH aqueous solution for Mg/Co-N-C, Co-N-C, Mg-N-C and commercial RuO2. The polarization curves as measured in linear sweep voltammetry interprets the onset potential of Mg/Co-N-C (1.40 V), which is close to that of commercial RuO2 (1.47 V), yet smaller than those of Mg-N-C (1.52 V) and Co-N-C (1.54 V) (Fig. 4a). Tafel plots of these catalysts are plotted in Fig. 4b and it is seen that the Mg/Co-N-C exhibits the small Tafel slope of 118.47 mV/dec, comparable to that of commercial RuO2 (117.13 mV/dec), which is lower than its single atom counterparts (128.49 mV/dec for Co-N-C and 167.20 mV/dec for Mg-N-C). The overpotential at a current density of 10 mA/cm2 and 100 mA/cm2 were calculated (Fig. 4c), which is superior to those of the SAC and competent to those of commercial benchmark. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) plots were shown in Fig. 4d, whereby the Mg/Co-N-C exhibits the lowest charge transfer resistance, in well accordance with the small Tafel slope. The durability of the catalyst was also assessed. As shown in Fig. 4e, Mg/Co-N-C exhibited only 27 mV increase in a prolonged chronopotentiometry test at a constant current density of 100 mA/cm2 for 48 h. Moreover, the polarization curves of Mg/Co-N-C only showed slight degradation after chronopotentiometry test, indicating promising stability during long-term OER operations (Fig. 4f). The XRD and HADDF-TEM showed no significant changes after OER tests, which demonstrate promising structural stability of the catalyst (Fig. S10 in Supporting information). Theoretical model with surface group modification reveals that the dual metal site catalysts can be stable in alkaline mediate because the multiple OH group oxidation demands high free energy (Fig. 4g). Attractively, the theoretical overpotential is reduced in the *OH and 2*OH modified catalysts, which is as small as 0.43 eV and 0.37 eV (Fig. 4h), further demonstrating its potential application in working condition.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Linear sweep voltammetry curves toward OER in 1 mol/L KOH. (b) Tafel plots of different catalysts. (c) Overpotential at different current densities. (d) EIS plots of different catalysts. (e) Chronopotentiometry curves of Mg/Co-N-C for 48 h at 100 mA/cm2. (f) Linear sweep voltammetry curves after chronopotentiometry test. (g) Free energy for protonation/hydroxyl group modification. (h) OER free energy diagram for Mg/Co site after surface modifications. | |

In conclusion, we designed a p-d coupled bimetal site as potential oxygen evolution electrocatalyst in sustainable energy conversion. The synergistic effect renders smooth adsorption/desorption of the key intermediates which not only makes a good balance between the interaction between *OH and *OH, but also exhibits good tolerant for OH− attacking, which guarantees superior performance in both catalytic activity and durability. This work presents a promising strategy of recognizing the roles of different metals and regulating their synergy, leading the exploration towards economy affordable high-performance catalysts.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this work.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank the financial supports from the Hebei Science Foundation (Nos. E2021203005, B2021203016), Hebei Education Department (No. C20210503), department of Education of Hebei province for Top Young Scholars Foundation (No. BJ2021042), Hebei provincial Department of Science and Technology (No. 226Z4404G). JW and JST are grateful for the grant (No. G2022003013L) and ComputeCanada for the allocation of computational resources. J. Wang would like to thank X. Yong for the fruitful discussions and the polish of English.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.109496.

| [1] |

J.W. Ager, A.A. Lapkin, Science 360 (2018) 707. DOI:10.1126/science.aat7918 |

| [2] |

B. Zhang, L. Sun, Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 2216. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00897C |

| [3] |

S. Xie, H. Jin, C. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2022) 107681. |

| [4] |

D. Cao, X. Shen, A. Wang, et al., Nat. Catal. 5 (2022) 193. DOI:10.1038/s41929-022-00752-z |

| [5] |

L.L. Cao, Q.Q. Luo, J.J. Chen, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4849. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12886-z |

| [6] |

S.M. Wang, Y.H. Jin, T. Wang, K.H. Wang, L. Liu, J. Materiomics 9 (2023) 269. DOI:10.1016/j.jmat.2022.10.007 |

| [7] |

Y.L. Sun, J. Wang, Q. Liu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 27175. DOI:10.1039/C9TA08616A |

| [8] |

J. Ma, B. Liu, R. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2585. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.108 |

| [9] |

J. Wang, R. Xu, Y.L. Sun, et al., J. Energy Chem. 55 (2021) 162. DOI:10.1016/j.jechem.2020.07.010 |

| [10] |

J.Y. Liu, X. Wan, S.Y. Liu, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2103600. DOI:10.1002/adma.202103600 |

| [11] |

B. Wu, T.X. Sun, Y. You, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202219188. DOI:10.1002/anie.202219188 |

| [12] |

E. Tiburcio, Y.K. Zheng, C. Bilanin, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 10342. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c02155 |

| [13] |

Q. Zhao, D. Zhao, L. Feng, et al., J. Materiomics 9 (2023) 362. DOI:10.1016/j.jmat.2022.09.015 |

| [14] |

Z.H. Pei, H.B. Zhang, Z.P. Wu, et al., Sci. Adv. 9 (2023) eadh1320. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.adh1320 |

| [15] |

M.H. Xie, B.W. Zhang, Z.Y. Jin, P.P. Li, G.H. Yu, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 13957. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c03432 |

| [16] |

N.H. Fu, X. Liang, X.L. Wang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 9450. |

| [17] |

X. Li, Z. Wang, Y. Tian, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 37 (2022) 107812. |

| [18] |

R. Akhter, S.S. Maktedar, J. Materiomics 9 (2023) 1196. DOI:10.1016/j.jmat.2023.08.011 |

| [19] |

X. Li, S. Duan, E. Sharman, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 10193. DOI:10.1039/D0TA01399D |

| [20] |

H. Xu, D. Cheng, D. Cao, X.C. Zeng, Nat. Catal. 1 (2018) 339. DOI:10.1038/s41929-018-0063-z |

| [21] |

W.A. Goddard, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 115 (2018) 5872. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1722034115 |

| [22] |

M. Bajdich, M. Garcia-Mota, A. Vojvodic, J.K. Norskov, A.T. Bell, J Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 13521. DOI:10.1021/ja405997s |

| [23] |

J. Wang, H.G. Li, S.H. Liu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 181. DOI:10.1002/anie.202009991 |

| [24] |

W. Hu, M. Zheng, H. Duan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1412. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.025 |

| [25] |

J. Wang, Z. Huang, W. Liu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 17281. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b10385 |

| [26] |

W. Wan, Y. Zhao, S. Wei, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 5589. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-25811-0 |

| [27] |

H. Li, J. Wang, R. Qi, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 285 (2021) 119778. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119778 |

| [28] |

Z. Lu, B. Wang, Y. Hu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 2622. DOI:10.1002/anie.201810175 |

| [29] |

H. Li, S. Di, P. Niu, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 15 (2022) 1601. DOI:10.1039/D1EE03194E |

| [30] |

T. He, Y. Chen, Q. Liu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202201007. DOI:10.1002/anie.202201007 |

| [31] |

S. Liu, Z. Li, C. Wang, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 938. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-14565-w |

| [32] |

T. Wang, X. Cao, H. Qin, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 21237. DOI:10.1002/anie.202108599 |

| [33] |

L. Gao, X. Li, Z. Yao, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 18083. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b07238 |

| [34] |

F. Xia, D. Tie, J. Wang, et al., Energy Storage Mater 42 (2021) 209. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2021.07.020 |

| [35] |

Z. Gu, J. Li, P. Song, et al., J. Materiomics 9 (2023) 1195. |

| [36] |

Z. Guan, K. Zou, X. Wang, Y. Deng, G. Chen, Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3847. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.05.013 |

| [37] |

X. Jiang, H. Jang, S. Liu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133 (2021) 4156. DOI:10.1002/ange.202014411 |

| [38] |

J. Zhang, Y.F. Zhao, W.T. Zhao, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. (2023) e202314303. |

| [39] |

L. Zhang, H. Jang, Y. Wang, et al., Adv. Sci. 8 (2021) 2004516. DOI:10.1002/advs.202004516 |

| [40] |

Z. Yang, W. Lai, B. He, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 13 (2023) 2300881. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202300881 |

| [41] |

F. Luo, A. Roy, L. Silvioli, et al., Nat. Mater. 19 (2020) 1215. DOI:10.1038/s41563-020-0717-5 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35