b School of Civil Engineering, Kashi University, Kashi 844000, China;

c Shanghai Baoye Engineering Technology Ltd., Shanghai 200941, China;

d College of Marine Ecology and Environment, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China

Gas adsorption has a wide range of applications in many fields such as environmental protection and chemical industry. The key to gas adsorption lies in the adsorbent. The factors that determine the performance of adsorbent include adsorbent pore structure (characterized by parameters such as specific surface area, pore volume, and pore size), and acid sites (characterized by density, type, and distribution). Zeolite is a porous crystalline material consisting of co-angular TO4 tetrahedral units interconnected to form a framework in which cavities and voids act as pore channels [1–3]. The composition of most zeolite frameworks is silicon aluminate. The aluminum makes the framework as a whole electronegative, and the material in the zeolite channel balances the framework charge [4–7]. For zeolite as a whole, a series of properties (pore size, pore volume, specific surface area, etc.) as porous materials are the focus of attention [8,9], and also the basis for its application in adsorbent and catalyst support. As for the local pore structure, acid sites with catalytic effect formed by electrostatic interactions near Al atoms in the framework [10,11] deserve further investigation. Pore structure and acid site, respectively, affect the properties of zeolite as an adsorbent.

The zeolite structure with only one single pore size limits molecular diffusion and thus affects its adsorption/catalytic performance [12–14]. To improve the diffusion environment of molecules and increase the mass transfer rate, hierarchical zeolite came into being. Hierarchical zeolite refers to zeolite with a mesoporous or macroporous network connecting micropores, thus forming multistage pore size. The structure of microporous and mesoporous connected is called hierarchical structure. Hierarchical zeolites have been shown to have better molecular transport than single pore size zeolites [15–17], which greatly improves the adsorption and catalytic behavior of zeolites. However, the kinetic diameters of different adsorbate molecules vary, and different catalytic reactions have different requirements for diffusion rates, which puts forward new requirements for hierarchical zeolite: precise design of pore size distribution based on synthesis to achieve the regulation of hierarchical structure.

The zeolite acid sites exist in the form of Brønsted acid site (BAS) and Lewis acid site (LAS). There is a close relationship between BAS and framework aluminum (AlF) [18–20]. BAS form in zeolites when protons balance the negative framework charge produced by Al replacing Si at the crystallographically different tetrahedral sites (T-sites). LAS is related to extra framework Al (EFAl), where cations such as Al3+, AlO+, Al(OH)2+, and Al(OH)2+ have vacant orbitals that can accommodate electron pairs and can serve as LAS sites. Former researches have revealed the acid sites in zeolites can be attached to the adsorbate molecules in the form of covalent or secondary bonds, and the adsorption energy is mostly above −50 kJ/mol, which belongs to the conventional chemisorption in the macroscopic sense [21,22]. Regulating the distribution, density and type of acidic sites in zeolites is essential to investigate the adsorption mechanism within zeolites and to improve the adsorption capacity.

Currently, there are more studies on zeolite hierarchical structures and acid site synthesis techniques, and fewer studies focusing on regulatory strategies. The difference between synthesis and regulation is that the purpose of synthesis is to obtain hierarchical structures and acid sites, while regulation is to achieve the design and adjustment of the parameters related to hierarchical structures and acid sites on the basis of synthesis. The review focuses on strategies for the modulation of zeolite hierarchical structures and acid sites from the perspective of basic synthetic methods. It also describes how these strategies enable the precise design of pore sizes and change the distribution, density and type of acid sites. On this basis, we will discuss the mechanism of zeolite adsorption on gas molecules from the perspective of hierarchical structure and acid sites. At the end, the adsorption properties of different zeolite adsorbents for inorganic and organic gases are listed. An outlook on the research trends of zeolite hierarchical structure and acid site modulation strategies is provided in this review.

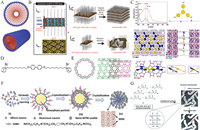

2. Regulating strategy of a hierarchical structure 2.1. Soft templating dominatedThe soft template which can form the hierarchical structure of zeolite is organic with hydrophilic groups. Surfactants and macromolecular polymers are the most commonly used two substances. Surfactants induce the crystallization of zeolite near the hydrophilic group outside the micelles (Fig. 1A) [23–25]. Zeolites with an ordered mesoporous hierarchical structure obtained by removing surfactants through calcination. The macromolecular polymer takes advantage of its larger size to directly form disordered mesopores in the zeolite as a "porogenic agents" [26,27].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (A) Agglomeration and stacking of surfactants (blue balls represent quaternary ammonium groups, red balls represent long alkyl chains). (B) Crystallization of MFI nanosheets and different forms of stacking. Reprinted with permission [28]. Copyright 2009, Elsevier. (C) UV–vis absorption spectra of the template and the stacking structure in the prepared zeolites. Reprinted with permission [29]. Copyright 2019, Wiley. (D) Schematic diagram of the bola form structure-directing agent. Reprinted with permission [30]. Copyright 2022, AAAS. (E) Schematic diagram of the structure of the single-walled zeolite nanotube. Reprinted with permission [30]. Copyright 2022, AAAS. (F) Mechanism for the synthesis of multi-stage pore MTW zeolites using bespoke simple organic molecules as templating agents is revealed. Reprinted with permission [31]. Copyright 2018, Wiley. (G) Proposed mechanism for amino acid-mediated mesoporous LTA formation. Reprinted with permission [32]. Copyright 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

In modern times, many unique structures of surfactants have been used as soft templates for the construction of hierarchical zeolites. These unique structures help form hierarchical zeolites in novel ways. Choi et al. designed a surfactant template with double quaternary ammonium groups to induce the formation of hierarchical zeolites (Fig. 1B) [28]. The surfactant has a C22 chain as the main chain and two C6 quaternary ammonium groups in series at the tail. The zeolite crystallizes into a sheet on the side of the micellar layer with quaternary ammonium groups, and the long enough alkyl hydrophobic chain prevents the zeolite from over-crystallizing in the b-axis direction, thus forming nano sheet zeolite. Subsequently, the alternating structure of zeolite nanosheets (thickness: 2 nm) - surfactant colloidal layer (thickness: 2.8 nm) was formed by stacking between the colloidal layers. The interlayer pores with mesopore size were formed after calcination, and the synthesis of the hierarchical structure was realized. In this study, the mesopores of zeolite are not formed by surfactant micelles, but by stacking between zeolite nanosheets. Coincidentally, Zhang et al. synthesized a surfactant with triphenyl benzene as the center and three branches of diquaternary ammonium groups [29]. The soft template forms a surfactant adhesive layer via the π-π interaction between phenyl groups, and the diquaternary ammonium groups on both sides of the adhesive layer can induce zeolite crystallization to form nanosheets with intervals (Fig. 1C). The size of the interlayer gap (2.2–3.0 nm) can vary with the length of branched alkanes (C6 ~ C10), thus forming the hierarchical structure of the zeolite. In addition to forming mesopores by stacking nanosheets, zeolite can also crystallize into zeolitic nanotubes to form mesopores. Korde et al. reported the use of an organic structure-directing agent (OSDA) in the form of a bola containing a central biphenyl molecule consisting of a C10 alkyl chain attached to a quinine terminal group (Fig. 1D) [30]. In the presence of π-π bonds, the biphenyl groups form a stable hydrophobic core along the axial direction of the nanotube. The zeolite crystallizes near the quaternary ammonium groups (Fig. 1E) and finally forms single-walled zeolite nanotubes with a diameter of about 3 nm. This work realizes the transformation of zeolites from two-dimensional to quasi-one-dimensional with a hierarchical structure. The hydrophobic alkyl chains in surfactants with special structures, although not inducing crystallization via micelles, are able to lamellar zeolite stacking or convolution to form more general "gaps" rather than pores in a narrower sense, resulting in hierarchical zeolites.

The key to the formation of hierarchical zeolites from macromolecules is to utilize the "porogenic" effect of the macromolecules. The Oswald ripening reaction is a small-molecule polymerization reaction that does not rely on chemical bond linkages. Zhang et al. designed a simple organic molecule with benzene as the center and only 7 C atoms on each side of the main chain. During crystallization, such small simple organic molecules can aggregate to the surface of amorphous aluminosilicate aggregates through the Ostwald ripening process to form nanoparticles with mesopore size (20–30 nm) (Fig. 1F) [31]. The difference between this process and the formation of mesopores from organic polymers is that the organic polymers themselves have mesopore sizes, while smaller simple organic molecules undergo Ostwald ripening to form mesopore-sized particles. Chen et al. synthesized hierarchical zeolite LTA with mesoporosity of 10–50 nm and mesoporosity peak of 15–20 nm by using small molecular amino acids such as l-carnitine, lysine, and their salt derivatives as templates [32]. Interestingly, after trying to shield the hydrogen bonds in amino acids, it was found that there are no mesopores in the synthesized zeolite. Therefore, it is speculated that amino acids rely on hydrogen bonding to form mesopore-scale groups (Fig. 1G), thereby acting as porogenic agents. Subsequently, they further explored the mechanism of the formation of mesopores by amino acid small molecules through quantum chemical calculation [33]. It is found that amino acid small molecules can be dissociated into small organic anions such as oxygen anions, nitro anions, and carbon anions. They can not only form mesopores by hydrogen bonding into mesoporous groups but also form mesopores by attacking framework silicon aluminum atoms to obtain hierarchical zeolites. The feasibility of amino acid as a soft template is verified by the mechanism. In addition, the soft template as an amino acid can be completely removed by water washing without producing any harmful substances, which is cleaner and more environmentally friendly than most soft templates.

The length of the soft template molecules, the type, number and position of the functional groups can be key factors influencing the formation of hierarchical structures. This helps zeolite crystals to crystallize into various structures and form mesopores, but it is therefore more difficult to achieve precise control of pore size and distribution. Moreover, the more complex the organic molecule, the more complicated the synthesis step and the more harmful substances are produced during calcination and removal. These are limiting factors for the synthesis of hierarchical zeolites from soft templates.

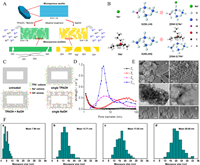

2.2. Hard templating dominatedThe hard template that can form mesopores in zeolite refers to the template material with a rigid structure. Carbon materials are representative of hard templates. Analogously to soft templates, zeolites crystallize around carbon particles, and then the templates are removed by calcination to get hierarchical zeolites. Madsen et al. firstly used commercial carbon black (CB) material to synthesize zeolite with a mesoporous hierarchical structure, in which the pore diameter was about 8 nm [34]. Since then, various carbon materials have been successively used in the design of mesopores in zeolites [35–37]. Jacobsen et al. investigated the synthesis process of mesoporous zeolites with carbon particles as hard templates and proposed a hierarchical structure formation mechanism: zeolite precursor gels encapsulate carbon particles and zeolites crystallize on the outer surface of carbon particles and in the mesoporous system [38]. The carbon matrix is removed by calcination to obtain hierarchical zeolite with mesopores, as shown in Fig. 2A [39]. The research of Cho et al. supplemented the application conditions of this mechanism [40]. They found that the pore size and wall thickness of CMK materials can affect the formation of zeolite mesopores. It is mainly reflected in the fact that the CMK-1 material with a too-small pore size (2.5 nm) and too-thin wall thickness (4 nm) is easily damaged by the growing zeolite crystals and loses its role as a template. However, CMK-3 with a larger pore size (10 nm) and wall thickness (5.1 nm) was used as a template to successfully generate medium pore zeolite with an MFI structure. This result indicates the condition for the carbon material to form mesopores: the rigidity of the template is not destroyed by the growing zeolite crystals. Based on understanding the pore-forming mechanism of carbon materials, scholars have further studied how carbon materials can regulate the pore structure. Schmidt et al. compared the process of forming mesopores between carbon nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes [41]. It is found that carbon nanoparticles tend to form disordered mesopores in the crystal, while carbon nanotubes tend to form channels with the mesoporous size that can connect the zeolite surface (Fig. 2B). It is proposed that the structure of carbon materials affects the mesoporous morphology and distribution of zeolite. Taking advantage of this, Xue et al. synthesized an array of carbon nanotubes and used them as hard templates to synthesize zeolite materials with array mesopores (Fig. 2C) [42]. The array of mesopores at about 10 nm was observed under EFSEM (Emission field scanning electron microscopy), which reflected the regulation of carbon material hard template on zeolite pore structure.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (A) Schematic diagram of the pore-forming mechanism of carbon templates (using MCM-22 zeolite synthesis as an example). Reprinted with permission [39]. Copyright 2010, American Chemical Society. (B) Different forms of pore formation for different structural carbon materials. Reprinted with permission [41]. Copyright 2012, Elsevier. (C) Pore formation by carbon nanotube arrays. Reprinted with permission [42]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier. (D) Carbon dot size and size distribution with corresponding ZSM-5 zeolites. Reprinted with permission [43]. Copyright 2020, Wiley. (E) Synthesis of mesoporous zeolites from corn stover waste as a template. Reprinted with permission [46]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier. | |

Although the structure of carbon materials used as hard templates is different, the regulation of zeolite pore size structure has a common purpose: using the template to customize mesoporous and achieve precise regulation. Zhao et al. prepared three kinds of carbon dots (CDots) with hierarchical sizes: CDots-1 (23 nm), CDots-2 (6, 9 nm), CDots-3 (5, 8, 18 nm) [43]. The ZSM-5 zeolite synthesized from these hierarchical carbon dots has two typical characteristics: (1) The mesopore size of the zeolite is very close to the size of the carbon dots (The pore sizes of the three zeolites were: 21.8 nm; 5.5, 8.5 nm; 4.8, 7.4, 17.5 nm, as shown in Fig. 2D); (2) each size of the hierarchical carbon dots can form mesopores with similar size. Therefore, it shows that the hierarchical carbon dots can largely determine the zeolite mesopore size and distribution, which provides an important reference value for the precise regulation of the zeolite mesopore. It is foreseeable that the precise regulation of zeolite hierarchical structure by designing carbon materials with different characteristics is an important development direction in the future.

In addition to carbon materials, polystyrene (PS) spheres and nano CaCO3 can also be used as hard templates to construct the hierarchical structure of the zeolite. Xu et al. used polystyrene spheres (about 580 nm in size) modified by anionic surfactants as templates to obtain ZSM-5 zeolite with macroporous structure through a hydrothermal synthesis calcination process [44]. The zeolite framework surrounding the macropore was observed under the electron microscope, which proved that the PS sphere as the template formed the macropore after calcination. Zhu et al. prepared a hydrophilic nano-CaCO3 with a hydroxyl group on its surface through fatty acid modification [45]. These highly active hydroxyl groups can cause strong interaction between silica gel and CaCO3. Finally, zeolite with a mesoporous hierarchical structure was obtained by washing CaCO3 with acetic acid. In recent years, there have also been studies on the formation of zeolite hierarchical structures using biomass materials as hard templates. Manikandan et al. extracted corn stem pith from corn agricultural waste as a template, and used high temperature to split the cellulose polymer in the stem pith into nano cellulose molecules [46]. Meanwhile, the zeolite precursor encapsulated outside was crystallized to obtain zeolite with a mesoporous MFI structure (Fig. 2E). Zhang et al. synthesized zeolite with a mesoporous hierarchical structure by using a carbon-based hard template formed in situ from soluble starch [47]. They studied the influence of starch content on the mesopore distribution of zeolite and found that there was a positive correlation between the mesopore diameter and the amount of starch. It was speculated that the reason was that the particle size of the accumulated starch carbide could affect the pore size. In addition, biomass materials such as sucrose and chitin can also be used for the formation and regulation of the mesoporous hierarchical structure of zeolite [48–50]. Despite the lower cost of these non-carbon hard template materials, the synthesis and control processes are not yet mature enough compared to carbon material synthesis processes. In addition, some non-carbon hard template materials (PS spheres, CaCO3) require surface modification for better integration into silica gel mixing systems. Otherwise, they will be discharged during the zeolite crystallization process, resulting in the inability to obtain layered zeolites. These have become constraints to the development of zeolites.

2.3. Atomic removalThe silicon and aluminum atoms in the zeolite can be stripped from the framework with a stripping agent to form larger pore sizes, resulting in graded zeolites. The mesopore of zeolite formed by atomic removal is affected by many factors, including the type of remover, the silicon-aluminum ratio of zeolite, and the zeolite structure. Groen et al. found that when using NaOH to desiliconize zeolite, the silicon atom in the zeolite with high silicon aluminum ratio was easily removed by NaOH, resulting in excessive destruction of zeolite framework (Fig. 3A) [51]. And zeolites with lower Si/Al ratio (Si/Al = 25–50) did not show this phenomenon, and mesoporous hierarchical structure was successfully formed. This is due to the fact that zeolites with a low Si/Al ratio contain more Al, which exists in the form of negatively charged AlO4− tetrahedra. These negatively charged AlO4− tetrahedra prevent OH− from attacking the surrounding silicon atoms due to the repulsion of homogeneity. Abello et al. compared the difference between organic hydroxides (tetrapropylammonium hydroxide, TPAOH, and tetrabutylammonium hydroxide, TBAOH. The organic bases in the following text refer specifically to these two organic alkalis.) and NaOH in removing silicon atoms from ZSM-5 zeolite, and concluded that organic alkali has two advantages: (1) In contrast to the rapid dissolution of the framework silicon in NaOH, the organic alkali is less reactive to silicon, which makes the desilication process easier to regulate; (2) The zeolite treated by organic alkali can directly produce mesoporous zeolite in the form of proton after calcination, while the zeolite obtained by NaOH needs to be ion-exchanged with ammonium salt to obtain mesoporous zeolite in the form of a proton [52]. The main method of desilication is alkali treatment, while dealumination can be achieved by calcination steam or acid treatment. Otomo et al. used calcination and steaming to remove Al atoms from zeolite, and observed the change of coordination number of EFAl by NMR, which proved the effectiveness of the two methods [53]. In addition, steam dealumination is more efficient than calcination, because the presence of H2O at high temperature and pressure can facilitate the hydrolysis of Si-O-Al bonds. Sheng et al. conducted steam treatment on HZSM-5 zeolite at different temperatures, and found that the mesopore volume of HZSM-5 zeolite after steam treatment is 0.12 cm3/g, while the mesopore volume of zeolite without steam treatment is only 0.07 cm3/g [54]. Del Campo et al. also found that the shape of the zeolite can greatly affect the formation of mesopores [55]. They used the desilication method to form the mesoporous hierarchical structure of the zeolite and found that this method worked well for the rod-shaped ZSM-22 zeolite, but only crystalline fragments were obtained by treating the needle-shaped zeolite in the same way. It is demonstrated that the alkali causes serious damage to the zeolite structure, and the zeolite framework has been disintegrated before the mesopores are formed. These results indicate the condition for atomic removal to form hierarchical zeolite is that the framework stability of zeolite is not destroyed by the removal agent. In addition, the concentration of the removal agent has also been proven to affect the generation of mesopores in zeolites. The more the concentration of the remover, the larger the pore volume of the zeolite formed. For example, ZSM-22 zeolite treated with 1.5 wt% HF has a mesopore volume of 0.295 cm3/g, whereas the sample obtained by treating the same parent with 0.7 wt% HF has a mesopore volume of only 0.146 cm3/g [56].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (A) Comparison of organic and inorganic bases for zeolite desilication. Reprinted with permission [52]. Copyright 2009, Elsevier. (B) Comparison of adsorption sites for TPA+ and Na+. Reprinted with permission [57]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (C) The formation mechanism of zeolite shell-mediated pores. Reprinted with permission [58]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (D) BJH porosity distribution of parent zeolite (ZP), as well as its NH4F (ZF) and caustic soda (ZB) etched derivatives and nanosheet zeolite (ZNS). Reprinted with permission [59]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (E) SEM and TEM images of NH4F etched zeolite. Reprinted with permission [59]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (F) The pore size distribution obtained after treatment of zeolites with different TPAOH/ (TPAOH + NaOH) concentration ratios (From a to d, the ratio is 1, 0.75, 0.5, and 0.25.). Reprinted with permission [58]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. | |

Atom removal is often restricted by the silicon-aluminum ratio of zeolite. This method is not universal, and the destruction of the stability of the framework by the remover cannot be ignored. Given the shortcomings of these atom removal methods, scholars have carried out improved research. Wan et al. treated zeolite with a mixed alkali of NaOH and tetrapropylammonium hydroxide (TPAOH), and found that TPA (+) can be adsorbed near some silicon atoms to provide protection, avoiding excessive destruction of the framework (Fig. 3B) [57]. Xu et al. took advantage of the protection of organic quaternary ammonium ions on the zeolite framework [58]. The regulation of the average pore size of the zeolite was realized by adjusting the percentage of TPAOH in the alkali mixture (the average pore sizes of zeolite corresponding to a percentage of TPAOH of 1, 0.75, 0.25, and 0 were 7.9, 13.71, 17.02, and 20.50 nm, respectively, as shown in Figs. 3C and F). This study is of great significance for the design of controllable mesoporous zeolites by atomic removal. Qin et al. obtained single-crystal hierarchical zeolite in the form of House of cards by etching ZSM-5 zeolite with NH4F solution [59]. NH4F can etch Si and Al at the same time at a similar rate. Since it is sensitive to structural stress and defect concentration areas, fluoride can preferentially attack the unstable defect areas in the crystal and avoid indiscriminate attacks on the framework atoms, thus maintaining the stability of the zeolite framework to a certain extent. The obtained hierarchical zeolite shows a pore size distribution of 10 nm to 100 nm (Figs. 3D and E). Without the preparation of a complex template, atom removal can skip the synthesis step and directly process the finished zeolite on the market to obtain the hierarchical zeolite. The number and diameter of mesopores formed by different concentrations and types of reagents are different, so the formation of hierarchical structures can be regulated by variation of reagent types and concentrations. However, the effect of the removal agent on the stability of the zeolite framework remains a limiting factor for atomic removal. Future research on the preparation of hierarchical zeolite by the atomic removal is likely to continue to focus on maintaining the stability of the zeolite framework and enhancing the universality of the method.

2.4. Crystal seeds dominatedCrystal seed is an additive in crystallization reaction. The main functions of crystal seed in the synthesis of zeolite include: increasing the crystallization rate; suppresses the growth of unwanted crystalline phases. In addition, the content of crystal seed in the zeolite precursor gel will significantly affect the crystallization rate (it is generally believed that the higher the content, the faster the crystallization rate). According to traditional studies, the function of crystal seeds is limited to the synthesis of microporous zeolites. However, recent studies have shown that crystal seeds may be able to induce branching growth of crystals to obtain zeolites with hierarchical structures. Jain et al. successfully synthesized columnar zeolites with a thickness of about 30 nm by using self-synthesized MEL zeolite seeds and grew "house of cards"-shaped nanosheets in the center of the sheets (Fig. S1A in Supporting information) [60]. N2 adsorption results showed the presence of mesopores and macropores in the intersecting nanosheet structures. The N2 adsorption results showed the presence of mesopores and macropores in the intersecting nanosheet structures. Related studies speculate that the MEL-type crystal species used may promote the branching growth of the crystals [61–63].

Dai et al. induced the growth of finned zeolite on the surface of ZSM-11 and ZSM-5 crystal seeds by the one-pot method [64]. The simulated mass transfer experiment results of benzene molecules showed that the mass transfer performance of the second-grown finned ZSM-5 zeolite was stronger than that of conventional ZSM-5 zeolite. Although there is no obvious evidence of mesopores in the finned zeolite (Fig. S1B in Supporting information), new gaps can be formed by inducing the secondary growth of the fins on the seed surface, which provides a new idea for obtaining hierarchical structure. The study of Liu et al. showed that zeolite seeds can also act as a pore-forming agent, through the dual role of external induction of zeolite crystallization and internal pore-forming to form hierarchical zeolite with internal mesopores [65]. The original zeolite seeds first formed hexagonal small ZSM-5 crystals in the aluminosilicate gel, and then dissolved through the Ostwald ripening to form hexagonal intracrystalline mesopores with a pore size of more than 20 nm (Fig. S1C in Supporting information). The zeolites synthesised by crystal seeds require almost no organic templating agents and are environmentally friendly. The hierarchical zeolite framework formed by crystal seed domination is complete and the zeolite is highly stable. As a consequence of these advantages, the crystal seed-led strategy is expected to become the main way of synthesising and regulating the hierarchical structure of zeolites in the future.

3. Regulating strategy of acidity in zeolites 3.1. In situ synthesis regulating strategiesIn-situ synthesis regulating refers to influencing the hydrothermal synthesis process by changing the type of raw materials, adding order, doping ions, etc., so that the acid sites in the obtained zeolite can be regulated.

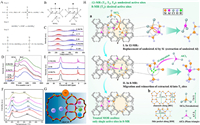

Aluminum in zeolites is closely related to acidic sites [66–68], and each AlF atom implies a BAS, thus regulating AlF also regulates the BAS. Raw materials influence the distribution of the AlF through their properties and the extent that atoms are aggregated in the gel. For example, a higher degree of networking of silicon atoms in tetraethoxysilane (TEOS) affects the binding of aluminum atoms in the framework, resulting in a greater distribution of BAS at zeolite pore crossings [69]. The mixing order of the gel also affects the distribution of AlF. The mixing sequence of "aluminum before silicon" (mixed aluminum source and TPAOH) resulted in a higher degree of aluminum agglomeration in the zeolite precursor gels as compared to "aluminum before silicon" (mixed aluminum source and TPAOH), which resulted in a more concentrated distribution of the BAS by arranging the AlF more in the form of "aluminum pairs" rather than "individual aluminum atoms" (Fig. 4A) [70]. From the perspective of the aluminum feedstock, aluminum hydroxide (AH) and sodium aluminate (SA) tend to form the tetra-coordinated aluminum species Al(OH)4− in the gel, which is more likely to form a series of identically-coordinated [Al-O-(Si-O)2-Al] aluminum pairs in the framework; whereas aluminum chloride (AC), aluminum sulfate (AS), and aluminum nitrate (AN) tend to form the hexa-coordinated aluminum species [Al(H2O)6]3+ (Fig. 4B), and this aluminum substance completes its crystallization before being fully transformed into the tetra-coordinated aluminum, leading to more dispersion of zeolites with BAS [71].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (A) Schematic diagram of single Al atom and Al pair. Reprinted with permission [70]. Copyright 2014, Elsevier. (B) Raman spectra of silica-aluminum mixtures of ZSM-5 zeolites with different aluminum sources. Reprinted with permission [71]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (C) 27Al MAS NMR spectra of FER samples calcined in the presence of different OSDA species. Reprinted with permission [72]. Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society. (D) Schematic diagram of the molecular structure of TMA, Pyr and HMI containing amino groups. Reprinted with permission [72]. Copyright 2011, American Chemical Society. (E) Effect of Na+, K+, and TMAda+ on aluminum distribution. Reprinted with permission [73]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (F) Crystallization mechanism of ZSM-11 zeolite mixed with different halogen anions. Reprinted with permission [74]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (G) Different distributions of BAS(I) and LAS(II) for H-MCM-22 zeolites with different boron contents. Reprinted with permission [76]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (H) FT-IR test results of pyridine after desorption of fresh zeolite and fresh Ag/zeolite catalysts at different temperatures. Reprinted with permission [78]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. | |

Organic structure-directing agents (OSDAs) mostly affect the AlF distribution and thus the BAS distribution through their own size. Molecules such as pyrrolidine, hexamethyleneimine, and 1,4-diazabicyclooctane are larger than tetramethylammonium, and when used as organic structural directing agents, they preferentially occupy the larger 12-magnetic resonances, which leads to a greater clustering of aluminum atoms in the smaller 8-magnetic resonances. In addition, OSDA may alter the intrinsic topological stability of Al at different crystallographic points (the effect of OSDA on Al is shown in Fig. 4C, characterized by 27Al NMR, the resonance at ~55ppm is assigned to Al atoms in tetrahedral coordination, and the resonance at ~0 ppm is assigned to Al atoms in octahedral coordination) [72], thus affecting the distribution of BAS. Furthermore, some amine OSDA (Fig. 4D), which have a stronger effect on AlO2− than the tetraalkyl quaternary ammonium cation, leading to a stronger BAS. The specific position and relative orientation of the cyclic amine molecules can also lead to a tendency for aluminum to be distributed at specific crystallization points, thus varying the BAS distribution.

In contrast to the effect of the feedstock on the overall crystallization environment, ions affect the arrangement of AlF by changing the local charge density. For example, TMAda(+) induces the formation of 12-membered rings (12 MR) with a single aluminum in the AlO2− tetrahedra, and Na+ induces the formation of 8 MR aluminum pairs adjacent to it. While K+, due to its larger size, tends to compete with TMAda(+), reducing the proportion of aluminum pairs in the product (Fig. 4E) [73]. Yuan et al. elucidated the effect of charge interactions on the distribution of AlF from the anionic point of view [74]. They synthesized ZSM-11 zeolites (Z11-Cl, Z11-Br, Z11-I) with the same silica-aluminum ratios by adding NaCl, NaBr, and NaI, respectively, to the raw materials. The total BAS densities were similar, but the outer surface BAS density of Z11-Cl was twice as much as the latter two. NMR analysis showed that Cl− has the highest hydration enthalpy (−369 kJ/mol) compared to Br− (−336 kJ/mol) and I− (−298 kJ/mol), and thus accelerates the nucleation and crystallization process of zeolites. During this process, the aluminum atoms on the outside of the entire gel system are too late to enter the central crystallization zone, and therefore more distributed on the outer surface of the zeolite (Fig. 4F), thus increasing the BAS density on the outer surface of the zeolite. In addition, there are interactions between the two variables, cation and OSDA, which together affect the acid site distribution. Bickel et al. synthesized MEL zeolites by using Na+ and TBA+ together as structure-directing agents and compared them with zeolites synthesized with pure TBA+ [75]. Na+ was found to compete with TBA+ for channel intersections, thus affecting the crystallization position of Al, resulting in less Al pairs and more dispersed BAS in the product.

When doping elements are added to zeolite synthesis precursors, the resulting zeolitic acid sites are related to the properties of the elements themselves. For example, Chen et al. substituted the B element for some of the Al elements in the zeolite framework [76]. MCM zeolites doped with different amounts of B were analyzed and found to have different BAS and LAS distributions, achieving the modulation of both acidic sites simultaneously (Fig. 4G). Zhao et al. used NH4F to homocrystallize the F element in place of some of the oxygen elements, and the higher electronegativity of the F atoms induced the acidicity of the silyl alcohol groups in their neighboring positions [77]. Other doping modes include Ag in zeolites as Ag+ or Ag2O nanoparticles [78], where Ag2O can be retained in zeolite mesopores and affect the strength of the BAS by acting on AlF (Fig. 4H), and La as trivalent cations in zeolite micropores, where simulations have shown that La3+ significantly alters the free energy distribution in its surroundings [79], thereby enhancing the surrounding BAS.

3.2. Post-synthetic processing regulating strategiesThe post-synthetic processing strategy involves reprocessing the finished zeolite, which has been crystallized, in order to change the density, distribution and type of acid sites in the zeolite. Reagent treatment is a common post-synthesis treatment strategy. Acidic reagents (with the exception of fluorinated acids) are able to remove AlF, resulting in a decrease in the density of BAS associated with it; on the other hand, when the acid dissociates insufficient H+ it is unable to attack the AlF, but it can undergo a substitution reaction with cations (e.g., Na+) in the zeolite cavities to form a new BAS [80,81]. whereas most of the aluminum-containing reagents are thought to significantly increase or enhance the acid sites in zeolites. Xie et al. modified Beta zeolite using NaAlO2 solution and found that the modified Beta zeolite had more BAS and LAS, presumably due to the fact that Al(OH)4− substances formed in the solution can undergo a holocrystalline substitution with silica tetrahedra (Figs. 5A and B) [82], thus increasing the BAS density, while the aluminum that is not doped into the framework stays in the zeolite pores to form LAS. He et al. modified ZSM-5 zeolite by impregnation with Al(NO3)3 (1.95 wt%) [83]. The NH3-TPD and FT-IR results of the obtained samples showed that: (1) The 400 ℃ peak shifted to the high-temperature band, indicating an increase in acidity; (2) The proportion of strong acid in BAS increased (before modification: 61.4%; after modification: 76.8%), and the LAS increased (before modification: 255 µmol/g; after modification: 284 µmol/g) (Figs. 5C–E). Al3+ entered into the zeolite pores to form EFAl substances, which were converted to LAS. Also, these EFAl substances interact with AlF to change the surrounding charge distribution and enhance the strength of BAS.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (A) Homocrystalline substitution of Si-Al atoms. Reprinted with permission [82]. Copyright 2002, Elsevier. (B) Possible tetrahedral environments of a silicon atom (marked with a cross) in the zeolite framework. Open circles, silicon; closed circles, aluminum; arrows, Si(0Al) sites. Reprinted with permission [82]. Copyright 2002, Elsevier. (C) The NH3-TPD curve of samples. The numbers refer to Si/Al. Catalysts with a theoretical Si/Al of 50 were obtained after impregnation with Al(NO3)3 and labeled Z-50(100) and Z-50(75). The numbers in D and E have the same meaning. Reprinted with permission [83]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (D) The IR spectrum of the OH stretching vibration region. Reprinted with permission [83]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (E) The 27Al MAS NMR spectrum. Reprinted with permission [83]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (F) NH3-TPD profiles of the prepared samples: a-HMOR, b-Cu/HMOR, c-Ni/HMOR, d-Co/HMOR, e-Zn/HMOR, and f-Ag/HMOR. Reprinted with permission [84]. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society. (G) Different metal dopant ions occupy different positions in the framework. Reprinted with permission [84]. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. (H) a: Sketch map of a typical treatment process, showing the directional migration of framework Al into T3 sites of the MOR zeolite via LPST. b: The topology of MOR and the steric configuration of SiCl4 and AlCl3 molecules with a kinetic diameter of 7.0 and 6.7 Å, respectively. Reprinted with permission [86]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. | |

The ability of metal cations to undergo substitution reactions with H+ on the zeolite framework is driven by differences in the strength of cation binding to the negatively charged zeolite framework. Metal cations of different sizes enter zeolite pores of different sizes. Wang et al. showed that ions such as Co2+, Ni2+, Cu2+, and Fe2+ of smaller sizes preferentially enter the 8 MR of filamentary zeolites for proton exchange [84], while Zn2+ of larger sizes can only enter the 12 MR for proton exchange (Figs. 5F and G). These result in a decrease of BAS in the zeolite. In addition, the remaining BAS concentration is located differently within the zeolite due to the different locations of the substitution, indirectly regulating the location of the BAS. In most cases, the metal cation exchanges with H+ representing the BAS and at the same time reduces the density of BAS in the zeolite. When the zeolite is treated by a combination of metal ion exchange and vaporization, it is possible to increase the BAS. Liu et al. used three substances, ZnCl2, Zn(NO3)2, and Zn(Ac)2, respectively, to ion exchange with NaY zeolite followed by vapor modification [85]. The results showed that only the BAS of the ZnCl2-treated zeolite increased from 326 µmol/g to 360 µmol/g before modification, while the strong BAS increased from 74 µmol/g to 88 µmol/g. Subsequent characterization of the tests showed that the binding of the ZnCl+ species to the framework aluminum left aluminum atoms close to the Zn doping sites unaffected by the vapor phase stripping while the framework aluminum away from Zn underwent a stripping-recrystallization process, and this reforming of aluminum atoms resulted in an increase in acid density. In addition, ZnCl+ enhanced the BAS sites around it, similar to the enhancement of BAS by some EFAl (e.g., Al(OH)2+). This research work inspired us to use a combination of regulating strategies for acid site density modification of zeolites. The integrated strategy of metal ion exchange and other modification methods can achieve a measured increase or decrease in acid site density and is expected to be the next generation of zeolite acid site regulation methods.

Changes of the acid sites in zeolites include increases and decreases for acid site density, conversion of BAS to LAS, and transfer of acid sites. We also hope to achieve some means of precisely regulating this process so that the zeolite has the catalytic properties we most desire for adsorption. SiCl4 is a reagent for achieving homo-crystalline substitution of silica-aluminum atoms in zeolite crystals, allowing the replacement of Si atoms in place of AlF atoms, releasing AlCl3. Liu et al. treated mordenite (MOR) with SiCl4 under low pressure, and SiCl4 entered 12 MR to isomorphically replace framework aluminum atoms, forming AlCl3 with smaller size [86]; AlCl3 can enter the smaller 8 MR and react with the siloxane defects therein, reintegrating aluminum atoms into the framework, realizing the directional transfer of AlF from 12 MR to 8 MR (Fig. 5H), thus changing the position of BAS directionally. This study provides a reference for the research on up-to-down precise regulation of BAS position.

3.3. Adsorbate regulationFor BAS and LAS in zeolites, both after pyridine adsorption exhibit wave number distributions in FT-IR around 1540 cm−1 and 1450 cm−1 [87–90], which is the main method for identifying and calculating BAS and LAS in zeolites and their densities. Acid sites that have adsorbed pyridine or other probe molecules lose their original catalytic efficacy and show a macroscopic decrease in acid density, just as the addition of an alkaline reagent to an acid solution decreases its acidity. He et al. measured a BAS density of 0.2 mmol/g in 12 MR of H-MOR zeolite adsorbed with supersaturated pyridine using 1H MAS NMR [91], which is only 20% of that of the original H-MOR sample; and the pyridine molecules failed to enter 8 MR to coordinate with the BAS therein due to pore size limitations (Fig. S2A in Supporting information). This study focuses on the role of pyridine molecules in regulating the density of acid sites. The role of the adsorbate molecule itself in regulating the position of the acid site has received little attention. A recent study has shown that the pyridine molecule is capable of indirect BAS position regulation [92]. FT-IR characterization of MOR zeolites after adsorption of pyridine showed a decrease in the amount of BAS in 12 MR and an increase in 8 MR. Whereas the NMR results showed the disappearance of the signal symbolizing the octahedral coordination of Al species and the enhancement of the signal symbolizing Si(OAl)(OSi)3. Together, the two characterization results explain the mechanism by which pyridine dynamically regulates the BAS: the entry of pyridine into 12 MR decreases the density of the BAS, while the potential resistance effect or change in charge distribution produced by pyridine, although it is unable to enter 8 MR, induces the octahedral-liganded Al species in 8 MR to re-frame and form the BAS (Fig. S2B in Supporting information). The result of this change is macroscopically reflected in the transfer of BAS from 12 MR to 8 MR in mordenite.

In addition to driving forces in the physical sense (spatial site resistance, electric field forces), some polar molecules change the type of acidic sites adsorbed by altering the chemical bonding. Li et al. used 13C-labeled acetone as a probe molecule, and observed the adsorption peaks of LAS on acetone by using 13C CP MAS NMR in conjunction with the results of high-resolution SXRD and NPD-refined crystallographic modeling [93]. It is believed that acetone adsorption induces a transition from BAS-type adsorption to FLP-type adsorption (frustrated Lewis electron pair, FLP). The mechanism is that the molecular polarity breaks the Al-O bond on the BAS, and the C = O of acetone binds to the backbone LAS in the form of Lewis base (LBS), which is manifested as a conversion of the adsorbed acetone BAS site to the FLP site (Fig. S2C in Supporting information). They also found that the change of FLP free energy was logarithmically correlated with polarity by further exploration. The higher the polarity, the lower the recombination energy required to induce the FLP state from the BAS state. This study is a pioneering finding that adsorbate molecules, especially polar molecules, induce the formation of FLP from BAS by breaking the Al-O bond, which leads to a change in the type of acid site. Investigating the effect of adsorbents on the change of acid sites in zeolites can study the mechanism of acid site transfer and transformation at the molecular level, and provide more new ideas for regulating the distribution and type of acid sites.

4. Mechanism of gas adsorption by zeolites 4.1. Facilitating transmission mechanisms — Hierarchical structureThe small pore size (<0.8 nm) and cavity diameter (<1.5 nm) of zeolites limit the transport rate of gas molecules and hinder their adsorption. Compared to the size of zeolite micropores (<2 nm), mesopores (2–50 nm) allow faster migration of guest molecules in the main framework [94,95]. Tang et al. compared the dynamic adsorption process of toluene on conventional ZSM-5 zeolite (CZ) and hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite (HZ) [96]. The results of diffusion rate simulation showed that the migration rate of toluene in HZ was 1.37 times higher than that in CZ. In addition, after five adsorption-desorption cycles, the adsorption capacity of HZ for toluene was still close to 100% (compared to the first adsorption capacity) (Fig. S3A in Supporting information), whereas the adsorption capacity of CZ was only 82%. This study demonstrated the advantages of hierarchical zeolite in terms of molecular transport rate and cycling performance.

The hierarchical structure promotes mass transfer. However, it is not the case that a larger pore size (or pore volume) facilitates molecular mass transfer. Panda et al. conducted CO2 adsorption tests (Fig. S3B in Supporting information) using 4A hierarchical zeolites with different mesoporous pore sizes (4.7, 5.5, and 6.0 nm) [97]; the adsorption capacities measured at 0 ℃ and 1 bar were 3.77, 3.41, and 2.72 mmol/g, respectively. The decrease in adsorption capacity with increasing pore size may be attributed to the fact that the pore size of the zeolite is too large to adsorb small molecules into the zeolite, which leads to a decrease in adsorption capacity.

The interconnected mesopores act as a facilitator of mass transfer and improve the adsorption or catalytic performance. Milina et al. first introduced the concept of "mesopore quality" and described it based on the connectivity of the pore network within the zeolite (Fig. S3C in Supporting information) [13]. In this study, the pore structure of alkali-modified hierarchical ZSM-5 zeolite was characterized (Fig. S3D in Supporting information), and the results of the characterization by scanning transmission secondary electron imaging combined with positron annihilation lifetime spectroscopy (PALS) revealed that zeolites with mesopores connected to the outer surface were found to be used for a longer period of time for the MTH reaction. It would be important to classify different types of mesopores to study molecular transport in zeolite pores. Kenvin et al. developed a differential hysteresis scanning (DHS) based on high-resolution argon adsorption coupled with nonlocal density flooding theory (NLDFT) for distinguishing between various types of mesopores in octahedral zeolites [98]. As shown in Fig. S3E (Supporting information), mesopores can be categorized into pyramidal (pyr), constricted (con), and occluded (oc) based on the relative relationship between mesopore diameter and window diameter. Subsequent PALS tests showed that pyramidal and contracted mesopores favored diffusion within the zeolite, whereas occluded mesopores did not improve transport properties. This approach has important applications in the study of pore connectivity and clogging. Hierarchical structure can be understood as a relative concept, and a hierarchical pore structure with connectivity relative to adsorbent molecules can effectively promote transport, improve the contact efficiency of molecules with adsorption sites, and increase the adsorption capacity.

4.2. Forces between zeolitic acid sites and adsorbate moleculesUnder van der Waals forces, molecules with a smaller molecular dynamics diameter than the zeolite pore diameter are adsorbed onto the surface of zeolite pore channels, cavities. In addition, the cavities where the cations are trapped have a high local polarity and can be used as adsorption sites for some polar molecules [99–101]. When classified by the relative magnitude of the bond energy, the adsorption mechanisms of zeolites on gases can be classified into three categories as follows:

(1) Secondary key role. Secondary bonds include hydrogen bonds and weaker intermolecular forces. Gas molecules such as N2 and CH4, which have an overall polarity of 0 and a low local polarity, are adsorbed in the cavity of the zeolite by the weak intermolecular force of "adsorbate-adsorbate-adsorbent" (Fig. S4A in Supporting information) [102]. And the inner adsorbate is capable of secondary bonding to the outer adsorbate together with the adsorbent (the inner wall of the zeolite pore channel), which is consistent with the description of physical adsorption in most models [103]. In addition, BAS in zeolite pore channels can be connected to oxygen-containing molecules (NOx, aldehydes, small molecules of carboxylic acids) in the form of hydrogen bonds (Fig. S4B in Supporting information) [104], and this force also falls under the category of secondary bonds. Molecular adsorption energies dominated by secondary bonding are in the range of approximately −15 kJ/mol to −30 kJ/mol (Fig. S4A) [102];

(2) Covalent bonding. The abundant off-frame cations in the zeolite pore channel are Lewis acids with empty orbitals that can admit electron pairs. Gas molecules that have bare lone pairs of electrons can form ligand covalent bonds with them [105]. The molecular adsorption energy dominated by covalent bonding is in the range of approximately −50 kJ/mol to −60 kJ/mol;

(3) Covalent bonding combined with secondary bonding. Refers to the hydrogen bonding-assisted, covalent bond-forming adsorption process. For example, in the adsorption of NOx by Fe-ZSM-5 and Co-ZSM-5 containing BAS, the BAS assists in the coordination of the adsorbate molecules with the transition metal cations (Fig. S4C in Supporting information) [106]. This type of mixing force has higher molecular adsorption energy than that dominated by covalent bonding forces alone (Fig. S4D in Supporting information).

The regulation of acid sites actually changes the strength, number and distribution of covalent and secondary bonding forces within the zeolite. A change in the strength of the acid sites implies a change in the bonding energy of the ligand covalent bonds between the adsorbed molecules and the zeolite, which in turn affects the adsorption energy and the temperature required for desorption. An increase in acid site density indicates an increase in the number of bonding sites (both secondary and covalent) in the zeolite, thus increasing the adsorption capacity. The distribution of bonding sites, on the other hand, affects the accessibility of acid sites, which can influence the performance of some adsorption or catalytic reactions.

5. Application of gas adsorptionCommon inorganic adsorbates include CO2, CO, N2, and NOx. Most of these molecular kinetic diameters are below 0.4 nm. The mechanism for the adsorption of non-polar gas molecules such as N2 by zeolites is dominated by secondary bonds, but there is also ligand covalent bond-dominated adsorption of N2 due to the presence of naked lone pair electrons outside the molecule, which tend to bind to empty orbitals (LAS) [107–109]. Although polar molecules such as CO and NOx are more likely to be bound by LAS in the zeolite pore channel, they are inherently concentrated as adsorbate molecules with small molecular diameters and can therefore also aggregate in the zeolite cavity in the form of "adsorbate-adsorbate-adsorbent". The mechanism of adsorption of most inorganic small molecules on zeolites can be summarised as follows: predominantly secondary bonds (van der Waals forces), and some ligand covalent bonds. The adsorption capacity of gas on zeolite is influenced not only by the nature of the adsorbate itself but also by external conditions such as temperature and air pressure, so that the adsorption data obtained under suitable operating conditions are more informative for a given adsorbate. The adsorption properties of some zeolites for inorganic gases and the corresponding working conditions are shown in Table S1 (Supporting information).

Unlike conventional inorganic gases, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are generally highly toxic and can cause irreversible damage to human health, as well as harming ecosystems through diffusion into the environment [110–113]. VOCs have a high polarity and a large molecular dynamics diameter. Many VOCs contain functional groups such as benzene rings and halogenated atoms in their molecules. The combination of these factors makes the mechanism by which VOCs molecules are adsorbed by zeolites more complex, and is a mixture of covalent and secondary bonding. In addition, water molecules compete for sorbents for VOCs molecules and many industrial emissions of VOCs exhaust gases carry a certain level of humidity, thus Table S2 (Supporting information) also focuses on the adsorption of VOCs by zeolite adsorbents at a certain level of humidity to evaluate the hydrophobicity of the zeolite.

6. Summary and outlookDisadvantages and advantages coexist in the regulating methods of hierarchical structures. The hard template method is easier to achieve precise regulation, and the soft template method can assist zeolites to form special hierarchical structures, but the templating agent methods in general all have the disadvantages of high cost and easy to cause pollution. Atomic removal methods are simple to operate, but tend to destroy the zeolite framework. The crystalline species can produce hierarchical structure by inducing crystallization through similar basic structural units, or form mesopores as template agent without removal, which can circumvent the above problems to a certain extent and has good development prospects, but there is still a need to research methods that can regulate hierarchical structure more precisely.

The regulating effect of the in situ synthesis method depends on the charge environment formed by the raw material during the crystallization process, which affects the distribution of acid sites through electrical repulsion, spatial site resistance, and other effects. The regulating effect of the post-synthesis method depends on the reagent, and changing the type and concentration of the reagent is more inclined to achieve the regulation of the acid site density. The regulating effect of adsorbed molecules on the acid sites depends on what kind of reaction takes place during the adsorption process. Simple substitution reactions only lead to a decrease in acid site density. It is noteworthy that some polar molecules (e.g., acetone) can induce the conversion of the acid site type, which may be a future direction for the regulation of the acid site type.

Structure determines function and function determines the application. The porous structure of zeolites and their internal acid sites determine their adsorption capacity, resulting in a wide range of applications in many areas. With the rapid development of zeolite hierarchical structure and acid site modulation strategies, it is reasonable to expect the creation of strategies that can modulate these two fundamental properties of zeolites at will, for applications in gas adsorption.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis research is supported by “Shanghai Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan”-Baoshan Transformation Development Science and Technology Special Project (No. 21SQBS01100), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22276137 and 52170087).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.109693.

| [1] |

D. Kerstens, B. Smeyers, J. Van Waeyenberg, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) 2004690. DOI:10.1002/adma.202004690 |

| [2] |

F. Mumtaz, M.F. Irfan, M.R. Usman, J. Iran, Chem. Soc. 18 (2021) 2215-2229. |

| [3] |

L.H. Chen, M.H. Sun, Z. Wang, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 11194-11294. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00016 |

| [4] |

P. Maina, M. Mbarawa, Energ. Fuel. 25 (2011) 2028-2038. DOI:10.1021/ef200156c |

| [5] |

K.S. Park, Z. Ni, A.P. Cote, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103 (2006) 10186-10191. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0602439103 |

| [6] |

S.B. Wang, Y.L. Peng, Chem. Eng. J. 156 (2010) 11-24. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2009.10.029 |

| [7] |

H. Hayashi, A.P. Cote, H. Furukawa, M. O’Keeffe, O.M. Yaghi, Nat. Mater. 6 (2007) 501-506. DOI:10.1038/nmat1927 |

| [8] |

M. Choi, H.S. Cho, R. Srivastava, et al., Nat. Mater. 5 (2006) 718-723. DOI:10.1038/nmat1705 |

| [9] |

A.H. Janssen, A.J. Koster, K.P. de Jong, J. Phys. Chem. B 106 (2002) 11905-11909. DOI:10.1021/jp025971a |

| [10] |

J. Brus, L. Kobera, W. Schoefberger, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 541-545. DOI:10.1002/anie.201409635 |

| [11] |

M. Gackowski, J. Podobinski, E. Broclawik, J. Datka, Molecules 25 (2020) 31. |

| [12] |

S.S. Huang, W. Deng, L. Zhang, et al., Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 302 (2020) 110204. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110204 |

| [13] |

M. Milina, S. Mitchell, P. Crivelli, D. Cooke, J. Perez-Ramirez, Nat. Commun. 5 (2014) 3922. DOI:10.1038/ncomms4922 |

| [14] |

F.L. Bleken, K. Barbera, F. Bonino, et al., J. Catal. 307 (2013) 62-73. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2013.07.004 |

| [15] |

S. Sartipi, K. Parashar, M.J. Valero-Romero, et al., J. Catal. 305 (2013) 179-190. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2013.05.012 |

| [16] |

L.H. Chen, M.H. Sun, Z. Wang, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 11194-11294. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00016 |

| [17] |

L.G. Possato, R.N. Diniz, T. Garetto, et al., J. Catal. 300 (2013) 102-112. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2013.01.003 |

| [18] |

A. Omegna, M. Vasic, J.A. van Bokhoven, G. Pirngruber, R. Prins, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 6 (2004) 447-452. DOI:10.1039/b311925d |

| [19] |

B.M. Murhy, J.C. Wu, H.J. Cho, et al., ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 1931-1942. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b03936 |

| [20] |

X.F. Yi, K.Y. Liu, W. Chen, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 10764-10774. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b04819 |

| [21] |

M.U.C. Braga, G.H. Perin, L.H. de Oliveira, P.A. Arroyo, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 331 (2022) 111643. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2021.111643 |

| [22] |

C. Hahn, J. Seidel, F. Mertens, S. Kureti, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24 (2022) 7493-7504. DOI:10.1039/D1CP05378G |

| [23] |

J.S. Beck, J.C. Vartuli, W.J. Roth, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114 (1992) 10834-10843. DOI:10.1021/ja00053a020 |

| [24] |

J. Kim, M. Choi, R. Ryoo, J. Catal. 269 (2010) 219-228. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2009.11.009 |

| [25] |

S. Che, A.E. Garcia-Bennett, T. Yokoi, et al., Nat. Mater. 2 (2003) 801-805. DOI:10.1038/nmat1022 |

| [26] |

J. Zhu, Y. Zhu, L. Zhu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 2503-2510. DOI:10.1021/ja411117y |

| [27] |

F.S. Xiao, L.F. Wang, C.Y. Yin, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (2006) 3090-3093. DOI:10.1002/anie.200600241 |

| [28] |

M. Choi, K. Na, J. Kim, et al., Nature 461 (2009) 246-249. DOI:10.1038/nature08288 |

| [29] |

Y. Zhang, X. Shen, Z. Gong, et al., Chemistry 25 (2019) 738-742. DOI:10.1002/chem.201804841 |

| [30] |

A. Korde, B. Min, E. Kapaca, et al., Science 375 (2022) 62-66. DOI:10.1126/science.abg3793 |

| [31] |

K. Zhang, S. Luo, Z. Liu, et al., Chemistry 24 (2018) 8133-8140. DOI:10.1002/chem.201706176 |

| [32] |

Z. Chen, J. Zhang, B. Yu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 4 (2016) 2305-2313. DOI:10.1039/C5TA09860B |

| [33] |

C. Chen, D. Zhai, L. Dong, et al., Chem. Mater. 31 (2019) 1528-1536. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b04433 |

| [34] |

C. Madsen, C.J.H. Jacobsen, Chem. Commun. 8 (1999) 673-674. |

| [35] |

J.B. Koo, N. Jiang, S. Saravanamurugan, et al., J. Catal. 276 (2010) 327-334. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2010.09.024 |

| [36] |

I. Schmidt, A. Boisen, E. Gustavsson, et al., Chem. Mater. 13 (2001) 4416-4418. DOI:10.1021/cm011206h |

| [37] |

Y.M. Fang, H.Q. Hu, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 10636-10637. DOI:10.1021/ja061182l |

| [38] |

C.J.H. Jacobsen, C. Madsen, J. Houzvicka, I. Schmidt, A. Carlsson, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 (2000) 7116-7117. DOI:10.1021/ja000744c |

| [39] |

N.B. Chu, J.Q. Wang, Y. Zhang, et al., Chem. Mater. 22 (2010) 2757-2763. DOI:10.1021/cm903645p |

| [40] |

H.S. Cho, R. Ryoo, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 151 (2012) 107-112. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2011.11.007 |

| [41] |

F. Schmidt, S. Paasch, E. Brunner, S. Kaskel, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 164 (2012) 214-221. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.04.045 |

| [42] |

C. Xue, T. Xu, J. Zheng, et al., Mater. Lett. 154 (2015) 55-59. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2015.04.059 |

| [43] |

S. Zhao, K.D. Kim, L. Wang, R. Ryoo, J. Huang, Adv. Mater. Interfaces 8 (2020) 2001846. |

| [44] |

L. Xu, S. Wu, J. Guan, et al., Catal. Commun. 9 (2008) 1272-1276. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2007.11.018 |

| [45] |

H. Zhu, Z. Liu, Y. Wang, et al., Chem. Mater. 20 (2008) 1134-1139. DOI:10.1021/cm071385o |

| [46] |

M. Krishnamurthy, K. Msm, C.Kanakkampalayam Krishnan, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 221 (2016) 23-31. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2015.09.022 |

| [47] |

M. Zhang, X. Liu, Z. Yan, Mater. Lett. 164 (2016) 543-546. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2015.10.044 |

| [48] |

H. Chen, X. Shi, F. Zhou, et al., Catal. Commun. 110 (2018) 102-105. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2018.03.016 |

| [49] |

G.V. Briao, S.L. Jahn, E.L. Foletto, G.L. Dotto, J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 508 (2017) 313-322. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2017.08.070 |

| [50] |

F.C. Drumm, J.S. de Oliveira, E.L. Foletto, et al., Chem. Eng. Commun. 205 (2018) 445-455. DOI:10.1080/00986445.2017.1402009 |

| [51] |

J.C. Groen, J.A. Moulijn, J. Perez-Ramirez, J. Mater. Chem. 16 (2006) 2121-2131. DOI:10.1039/B517510K |

| [52] |

S. Abelló, A. Bonilla, J. Pérez-Ramírez, Appl. Catal. A 364 (2009) 191-198. DOI:10.1016/j.apcata.2009.05.055 |

| [53] |

R. Otomo, T. Yokoi, J.N. Kondo, T. Tatsumi, Appl. Catal. A 470 (2014) 318-326. DOI:10.1016/j.apcata.2013.11.012 |

| [54] |

Q. Sheng, K. Ling, Z. Li, L. Zhao, Fuel Process. Technol. 110 (2013) 73-78. DOI:10.1016/j.fuproc.2012.11.004 |

| [55] |

P. del Campo, P. Beato, F. Rey, et al., Catal. Today 299 (2018) 120-134. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2017.04.042 |

| [56] |

A.K. Jamil, O. Muraza, M.H. Ahmed, et al., Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 260 (2018) 30-39. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.10.016 |

| [57] |

W. Wan, T. Fu, R. Qi, J. Shao, Z. Li, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55 (2016) 13040-13049. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.6b03938 |

| [58] |

Y. Xu, J. Wang, G. Ma, J. Lin, M. Ding, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 7 (2019) 18125-18132. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b05217 |

| [59] |

Z. Qin, L. Pinard, M.A. Benghalem, et al., Chem. Mater. 31 (2019) 4639-4648. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b04970 |

| [60] |

R. Jain, A. Chawla, N. Linares, J.Garcia Martinez, J.D. Rimer, Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) e2100897. DOI:10.1002/adma.202100897 |

| [61] |

X. Zhang, D. Liu, D. Xu, et al., Science 336 (2012) 1684-1687. DOI:10.1126/science.1221111 |

| [62] |

P. Kumar, D.W. Kim, N. Rangnekar, et al., Nat. Mater. 19 (2020) 443-449. DOI:10.1038/s41563-019-0581-3 |

| [63] |

R. Jain, J.D. Rimer, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 300 (2020) 110174. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110174 |

| [64] |

H. Dai, Y. Shen, T. Yang, et al., Nat. Mater. 19 (2020) 1074-1080. DOI:10.1038/s41563-020-0753-1 |

| [65] |

Y. Liu, Q. Zhang, J. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202205716. DOI:10.1002/anie.202205716 |

| [66] |

J. Dedecek, E. Tabor, S. Sklenak, ChemSusChem 12 (2019) 556-576. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201801959 |

| [67] |

N. Wang, M.H. Zhang, Y.Z. Yu, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 169 (2013) 47-53. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2012.10.019 |

| [68] |

B.C. Knott, C.T. Nimlos, D.J. Robichaud, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 770-784. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b03676 |

| [69] |

T. Liang, J. Chen, Z. Qin, et al., ACS Catal 6 (2016) 7311-7325. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.6b01771 |

| [70] |

V. Pashkova, P. Klein, J. Dedecek, V. Tokarová, B. Wichterlová, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 202 (2015) 138-146. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.09.056 |

| [71] |

M. Xing, L. Zhang, J. Cao, et al., Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 334 (2022) 111769. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2022.111769 |

| [72] |

Y. Roman-Leshkov, M. Moliner, M.E. Davis, J. Phys. Chem. C 115 (2011) 1096-1102. DOI:10.1021/jp106247g |

| [73] |

J.R. Di Iorio, S. Li, C.B. Jones, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 4807-4819. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b13817 |

| [74] |

K. Yuan, X. Jia, S. Wang, et al., Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 341 (2022) 112051. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2022.112051 |

| [75] |

E.E. Bickel, A.J. Hoffman, S. Lee, et al., Chem. Mater. 34 (2022) 6835-6852. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.2c01083 |

| [76] |

J. Chen, T. Liang, J. Li, et al., ACS Catal. 6 (2016) 2299-2313. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b02862 |

| [77] |

R. Zhao, S. Li, L. Bi, et al., Catal. Sci. Technol. 12 (2022) 2248-2256. DOI:10.1039/D1CY01793D |

| [78] |

H. Yang, C. Ma, X. Zhang, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 1248-1258. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b02410 |

| [79] |

R.C. Shiery, S.J. McElhany, D.C. Cantu, J. Phys. Chem. C 125 (2021) 13649-13657. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c02932 |

| [80] |

D.V. Peron, V.L. Zholobenko, J.H.S. de Melo, et al., Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 286 (2019) 57-64. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.05.033 |

| [81] |

G. Park, J.M. Kang, S.J. Park, et al., Mol. Catal. 531 (2022) 112702. DOI:10.1016/j.mcat.2022.112702 |

| [82] |

Z.K. Xie, J.Q. Bao, Y.Q. Yang, Q.L. Chen, C.F. Zhang, J. Catal. 205 (2002) 58-66. DOI:10.1006/jcat.2001.3421 |

| [83] |

X. He, Y. Tian, L. Guo, C. Qiao, G. Liu, J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 165 (2022) 105550. DOI:10.1016/j.jaap.2022.105550 |

| [84] |

S. Wang, W. Guo, L. Zhu, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 119 (2014) 524-533. |

| [85] |

P. Liu, Z. Li, X. Liu, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 9197-9214. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c01181 |

| [86] |

R. Liu, B. Fan, W. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202116990. DOI:10.1002/anie.202116990 |

| [87] |

C. Chizallet, S. Lazare, D. Bazer-Bachi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 12365-12377. DOI:10.1021/ja103365s |

| [88] |

L.A. Chen, J.H. Li, M.F. Ge, Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (2010) 9590-9596. DOI:10.1021/es102692b |

| [89] |

W. Zhou, J. Luo, Y. Wang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 242 (2019) 410-421. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2018.10.006 |

| [90] |

J.N. Hall, P. Bollini, ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 3750-3763. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c00399 |

| [91] |

T. He, X. Liu, S. Xu, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 120 (2016) 22526-22531. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b07958 |

| [92] |

R. Liu, B. Fan, Y. Zhi, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202210658. DOI:10.1002/anie.202210658 |

| [93] |

G. Li, C. Foo, X. Yi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 8761-8771. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c03166 |

| [94] |

Y.Y. Yue, X.X. Guo, T. Liu, et al., Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 293 (2020) 109772. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.109772 |

| [95] |

L. Zhang, W.B. Shan, M. Ke, Z.Z. Song, Catal. Commun. 124 (2019) 36-40. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2019.02.025 |

| [96] |

Q. Tang, W. Deng, D. Chen, D. Liu, L. Guo, Dalton Trans. 50 (2021) 16694-16702. DOI:10.1039/D1DT02869C |

| [97] |

D. Panda, E.A. Kumar, S.K. Singh, J. CO2 Util. 40 (2020) 101223. DOI:10.1016/j.jcou.2020.101223 |

| [98] |

J. Kenvin, S. Mitchell, M. Sterling, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 26 (2016) 5621-5630. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201601748 |

| [99] |

X. Li, F. Rezaei, A.A. Rownaghi, Micropor. Mesopor. Mat. 276 (2019) 1-12. DOI:10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.09.016 |

| [100] |

S.F. Li, H. Yan, Y.B. Liu, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 445 (2022) 136670. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2022.136670 |

| [101] |

X.F. Wei, Y. Li, Z.L. Hua, L.S. Chen, J.L. Shi, ChemCatChem 12 (2020) 6285-6290. DOI:10.1002/cctc.202001363 |

| [102] |

A. Orsikowsky-Sanchez, F. Plantier, C. Miqueu, Adsorption 26 (2020) 1137-1152. DOI:10.1007/s10450-020-00206-7 |

| [103] |

M. Thommes, K. Kaneko, A.V. Neimark, et al., Pure Appl. Chem. 87 (2015) 1051-1069. DOI:10.1515/pac-2014-1117 |

| [104] |

S. Namuangruk, D. Tantanak, J. Limtrakul, J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 256 (2006) 113-121. DOI:10.1016/j.molcata.2006.04.060 |

| [105] |

A. Sayari, Y. Belmabkhout, R. Serna-Guerrero, Chem. Eng. J. 171 (2011) 760-774. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2011.02.007 |

| [106] |

T.M. Ismail, K.P. Prasanthkumar, C. Ebenezer, et al., Langmuir 38 (2022) 10492-10502. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c01270 |

| [107] |

H.D. Sun, Z.L. Xie, H.L. Wang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 10 (2022) 8854-8859. DOI:10.1039/D2TC01089E |

| [108] |

C.W. Liu, Q.Y. Li, C.Z. Wu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 2884-2888. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b13165 |

| [109] |

Q. Shen, Z. Lu, F. Bi, et al., Fuel 343 (2023) 128012. DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128012 |

| [110] |

F. Bi, S. Ma, B. Gao, et al., Fuel 344 (2023) 128147. DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128147 |

| [111] |

Q. Shen, Z. Lu, F. Bi, et al., Sep. Purif. Technol. 325 (2023) 124707. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124707 |

| [112] |

F. Bi, Z. Zhao, Y. Yang, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 56 (2022) 17321-17330. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.2c06886 |

| [113] |

X. Zhang, S. Ma, B. Gao, et al., J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 651 (2023) 424-435. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2023.07.205 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35