Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are reactive chemical species formed due to environmental factors like UV or X-rays or to normal metabolic processes in human cells [1,2]. ROS are essential cellular signaling molecules that regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [3]. Excess ROS production overwhelms the antioxidant defense mechanisms, leading to oxidative stress that damages biomolecules like DNA, proteins, and lipids [4]. Regulating intracellular ROS was explored using ROS-generating nanosystems for disease therapy [5-8]. ROS-generating nanosystems increase oxidative stress in diseased cells and tissues selectively to induce apoptosis or eradicate diseased cells or pathogens [9]. Tumor cells that exhibit higher basal ROS levels are more susceptible to further ROS insults, inducing tumor cell death [10,11]. ROS-generating nanosystems are usually integrated with metal nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and quantum dots that can generate ROS through catalysis, photothermal conversion, or surface plasmon resonance [5,11-13]. Developing ROS-mediated nanoparticles as nanomedicine was crucial for disease therapy [14,15].

DNA serves as the genetic material of all living organisms. DNA has been utilized as a fundamental component for creating synthetic materials [16-18]. Compared to traditional polymers, DNA offers unique advantages over polymers in creating functional materials [19-21]. First, DNA oligonucleotides are commercially synthesized through standard phosphoramidite chemistry, ensuring high purity and cost-effectiveness [19]. Second, DNA molecules adhere to the Watson-Crick base-pairing principles during interactions, facilitating the precise and programmable fabrication of DNA-based functional materials with exceptional accuracy [22]. Third, DNA-based functional materials with the desired merits of rigidity and flexibility can be constructed by selecting single-stranded, double-stranded, or hybrid DNA to meet the specific requirements. Moreover, DNA aptamers can be isolated from synthetic libraries targeting various molecules, from sizable proteins to minute chemicals, demonstrating strong affinities and specificities in binding interactions [23]. DNA also possesses merits encompassing traits like reversibility, stability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability. Consequently, synthetic DNA presents a promising prospect for fabricating functional materials and integrating with ROS-based nanomedicine. Using DNA-based nanoparticles as ROS-generating nanosystems presents significant advantages in nanomedicine because the programmability, biocompatibility, and biodegradability enable precise control over ROS generation. At the same time, targeted delivery and activation enhance their therapeutic or diagnostic efficacy. ROS-generating DNA-based nanoparticles hold great promise for future advancements in nanomedicine, paving the way for more effective and personalized disease treatments.

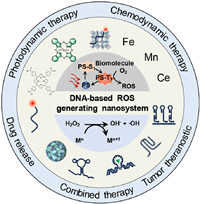

This review provides a comprehensive overview of the current state-of-the-art and prospects of DNA-based nanoparticles as ROS-generating nanosystems in nanomedicine. By elucidating the construction and applications of ROS-generating nanosystems, focusing on their diagnostic and therapeutic prospects. The scope includes: (1) Construction of DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems, including photodynamic therapy (PDT) system and chemodynamic therapy (CDT) system. (2) Applications of PDT and CDT nanosystems, focusing on intracellular redox homeostasis regulation, drug release, and tumor therapy (Fig. 1). This review will advance knowledge in intracellular ROS regulation for disease theranostic.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Construction and applications of DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystem. | |

ROS-generating nanosystems upregulate the intracellular redox status with interventions, such as chemical species or light. Chemical characteristics and biological behaviors of DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems depend on the material chemistry for ROS production. Photosensitizers such as Chlorin e6 (Ce6), protoporphyrin, or zinc phthalocyanine respond to exogenous light irradiation and enable remote-controlled photocatalytic generation of ROS for PDT. CDT agents, such as Fe3O4, FeS, MnO2, and CuS, convert H2O2 in endogenous biological environments into highly cytotoxic •OH for CDT. The transition of energy into ROS depends on the related chemical reactions. PS or CDT agents transfer exogenous optical or chemical energy into ROS. This section will highlight the construction of DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems, including DNA-based PDT nanosystems and CDT nanosystems and the latest studies on this topic have been outlined in Tables S1 and S2 (Supporting information).

2.1. Design DNA for construction of ROS-generating nanosystemsThe cross-linking-based strategy is a common method to prepare DNA materials by utilizing the specific complementary binding and pairing stability between single stranded DNA. DNA nanogels can be constructed by cross-linking using Y-shaped DNA (Y-DNA), linker DNA (L-DNA), and end DNA (E-DNA). Y-DNA consisted of three DNA chains (Y1, Y2, and Y3), forming a structure with three arms, each with sticky ends complementary to L-DNA. Y-DNA and L-DNA combined to create a vast cross-linked DNA network, while E-DNA regulated the growth of this structure [28]. As prepared DNA structure can form highly stable three-dimensional structures and achieve precise control over their physical, chemical, and biological properties. Utilizing photosensitizer-modified DNA chains to construct photosensitizer-loaded DNA structure can be obtained by cross-linking onto DNA backbones of DNA structures. Guo et al. reported a photosensitizer-modified DNA tetrahedron framework by assembling four photosensitizer-grafted DNA chains synthesized by graft pheophorbide a photosensitizer on the DNA backbone. The photosensitizer-modified DNA tetrahedrons were further packed with cell death-ligand 1 small interfering RNA, forming stable nano gels with enhanced aqueous solubility, controlled drug loading, and protection against enzymatic degradation, leading to promoted antitumor immune response and enhanced antitumor efficacy (Fig. 2a) [24].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Design DNA for ROS-generating nanosystems. (a) Cross-linking-based strategy to counter a, DNA nanogel-based ROS-generating nanosystem with PD-L1 siRNA, photosensitizer conjugated DNA tetrahedral framework, pheophorbide A (PPA), and siRNA assemble. Reprinted with permission [24]. Copyright 2022, American Association for the Advancement of Science. (b) RCA-based strategy to contrast a DNA nanogel-based ROS-generating nanosystem. Reprinted with permission [25]. Copyright 2019, John Wiley and Sons. (c) DNA nanocomplex programmed with DNAzymes and Zn-Mn-ferrite for CDT. Reprinted with permission [26]. Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons. (d) Intelligent nanomachine with DNAzyme logic system for CDT. Reprinted with permission [27]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Rolling circle amplification (RCA) is an enzymatic method to produce single-stranded DNA with a circular DNA template. This method can synthesize ultralong DNA chain of up to 20,000 nucleotides that can cross-link to form hydrogels [29,30]. Pan et al. presented a DNA nanosponge synthesized through RCA to enhance tumor PDT. Circular DNA templates encoded with sgc8c aptamer and G-quadruplex were used to create DNA nanosponges of NSPA and NSPC. The sgc8c aptamer targeted tumor cells that overexpress the tyrosine-protein kinase 7, while the G-quadruplex binds to the porphyrin photosensitizer TMPyP4. The NSPA variant included a complementary sequence for HIF-1a antisense DNA, contributing to tumor resistance against PDT. During the assembly of NSPC, the photosensitizer and catalase were simultaneously integrated through the RCA reaction. The resulting products were replicated copies fused with therapeutic molecules, achieved through nucleic acid amplification and assembly. Aided by HIF-1a antisense sequences, NSPA could bind to HIF-1a mRNA in tumor cells, effectively suppressing HIF-1a expression, increasing the sensitivity of PDT and improves overall treatment efficacy (Fig. 2b) [25]. Yao et al. developed a DNA nanocomplex called DNC-ZMF via RCA for CDT. The Zn-Mn-Ferrite (ZMF) adsorbed onto the RCA generated DNA nanocarrier (DNC) through electrostatic interactions. The DNC consisted of two essential sequences: AS1411 aptamers and cascade DNAzymes. The AS1411 aptamers facilitated specific binding of the DNC-ZMF to tumor cells that overexpress nucleolin. This binding triggered endocytosis and subsequent escape from the lysosomes. The ultra-long DNA chain was cleaved by DNAzyme-1 with the help of Zn2+ as a cofactor. This cleavage process resulted in the formation of fragments containing DNAzyme-2. Subsequently, DNAzyme-2 cleaved the mRNA with Mn2+ as a cofactor. This cleavage caused the downregulation of early growth response protein 1, which inhibited tumor cell proliferation and promoted apoptosis. The targeted therapeutic effects and the decomposition of ZMF resulted in the release of Zn2+, Mn2+, and Fe2+ ions. These ions catalyzed endogenous H2O2 to produce cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals, facilitating CDT of tumor bearing mice (Fig. 2c) [26].

Wang et al. presented a DNA-templated assembly approach to fabricate metal-organic framework (MOF) nanoparticles to develop an acid-activated cascade reaction system for enhanced tumor CDT. Fe-DNA nanoparticles were synthesized initially using a coordination-driven self-assembly technique. Fe2+ ions were mixed with poly A20 DNA to create the nanospheres. The nanospheres showed a homogeneous distribution of nitrogen, phosphorus, and iron, confirming the successful incorporation of Fe2+ ions into the DNA structure. The nanospheres formed due to the coordination interaction between Fe2+ ions and DNA molecules, which possessed phosphate binding sites, nitrogen atoms, and oxygen atoms on the nucleobases. The size of the nanospheres could be adjusted by changing the molar ratio of Fe2+ ions to DNA. The different nucleobases of DNA exhibited different coordination affinities to Fe2+, resulting in variations in the formation of Fe-DNA nanospheres. The Fe-DNA nanospheres were synthesized with precise control over their size and composition [31].

Logic-gated strategy is promising in construct DNA nanostructures for nanomedicine. Precision medicine is defined by the National Institutes of Health as effective disease treatment. In recent years, intelligent nanomachines can perform complex operations in cells and organisms, offering new insight into precision medicine. The ideal machine behaves like a human, sensing, processing, and responding to external information. Wang et al. created an innovative nanomachine by combining a dual-responsive DNAzyme logic system with a Prussian blue analog MOF. The DR-DNAzyme logic gate acted as the control center of the nanomachine, detecting high levels of miR-21 and H2O2 in cancer cells and activating accordingly. Once activated, the DR-DNAzyme inhibited catalase expression, resulting in the accumulation of H2O2. Simultaneously, the increased H2O2 amount was an input signal to activate the logic system. This work demonstrated potential of DNAzymes in logic gated DNA networks and nanomachines in personalized medicine (Fig. 2d) [27].

2.2. Construction of DNA-based PDT nanosystemPDT uses photosensitizers activated by light to induce cell death via ROS. However, the low solubility of photosensitizers in blood reduces PDT efficacy. Conjugate photosensitizer with DNA was a promising solution. Covalent conjugation binds the photosensitizer chemically to DNA through a reaction, such as linking to amino acid residues on DNA strands via acylating links. Covalent binding is more stable but may impact DNA's biological functions. Non-covalent conjugation involves physical adsorption of the photosensitizer onto DNA's surface through van der Waals forces or electrostatic effects. Photosensitizer molecules can be noncovalently inserted into the hydrophobic pockets of the DNA double helix and further conjugated to nanoparticles, such as porous silica nanoparticles, H-BN nanosheets, or nano MOFs, achieving efficient tumor therapy. The binding is weaker and the photosensitizer could detach more easily from DNA. However, this approach has less effect on DNA's biological applications. Mesoporous silica, a class of porous material, possesses a highly ordered, hexagonally packed cylindrical pore structure with pore diameters typically in the 2–50 nm range, allowing to accommodate large payloads of drugs. Yuan et al. introduced a new method to improve photodynamic cancer therapy using a hybrid virus-like mesoporous silica nanoparticle and DNA nanogel. The virus-like mesoporous silica nanoparticle acted as the core of the H-DNA nanogel, and ultra-long DNA chains are assembled to form the DNA nanogel layer. The DNA chains were encoded with a sequence of G-quadruplex-structured modules to integrate zinc phthalocyanine photosensitizer, yielding 1O2 generation to induce more intensive cell apoptosis (Fig. S1a in Supporting information) [32]. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), a class of porous crystalline materials, comprise metal ions or clusters linked by organic ligands with vast structural and chemical tunability. Common metal nodes, including copper, zinc, and chromium, are coordinated with multidentate organic ligands such as tertiary amines and carboxylic acids. MOFs possess precisely defined nanoscale pores and channels with adjustable sizes and functionalities. The uniformly sized pores, large interior surface areas, and designable functionality of MOFs make them promising for photosensitizer loading. Li et al. synthesized a nano MOF based on tungsten, which was composed of dinuclear W(VI) secondary building units and photosensitive 5, 10, 15, 20-tetra (p-benzoate) porphyrin ligands. The cationic complex released tumor-associated antigens and deliver immunostimulatory CpG oligodeoxynucleotides, thereby promoting the maturation of dendritic cells (Fig. S1b in Supporting information) [33]. Hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets are a two-dimensional material similar to graphene but composed of boron and nitrogen atoms, crystallizing in a hexagonal lattice structure. Individual hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets provide stiffness and flexibility with sp2 hybridized in-plane bonding. In contrast, interlayer bonding between sheets shows weak van der Waals interaction, allowing for easy exfoliation into single or few-layer nanosheets. The thin structure and surface properties allow for drug loading. Liu et al. developed a hexagonal boron nitride nanosheet coated with DNA conjugated to the photosensitizer (CuPc), which improved solubility for effective PDT through CuPc intercalation into the DNA hydrogel. The PDT could successfully eliminate early-stage tumors (Fig. S1c in Supporting information) [34]. Covalently bonding photosensitizers with DNA is an efficient way to attach photosensitizer molecules to DNA strands. Amidation or click chemistry are usually adopted method due to the high chemical selectivity. Liu et al. constructed a photosensitive, GSH-responsive nanocarrier using a DNAzyme covalently conjugated with a photosensitizer (Ce6-DNAzyme). The formed Ce6-DNAzyme/[Cu(tz)] can be endocytosed by a cancer cell and disassembled by the overexpressed GSH to trigger DNAzyme release and catalytically cleave target mRNA in cancer cells. Under 660 nm light, Ce6-DNAzyme/[Cu(tz)] produced 1O2 for PDT. Under 808 nm light, Ce6-DNAzyme/[Cu(tz)] generated •OH, providing effective PDT (Fig. S1d in Supporting information) [35].

PDT requires a specific light source to activate photosensitizer on the skin or within the body. Due to the potential damage of short wavelength light to healthy tissues or eyes, the light source parameters, including intensity, wavelength, location, and exposure time, must be carefully controlled, ensuring efficient PDT. Visible light in wavelengths ranging from 400 nm to 700 nm is typically used as active photosensitizer but restrained by the limited tissue penetration [36]. Near-infrared light was explored for PDT with higher tissue penetration than UV light (Fig. S2a in Supporting information). Upconversion luminescent nanoparticles (UCNPs) are a unique type of nanomaterials that can remarkably convert near-infrared (NIR) into visible or ultraviolet. The upconversion luminescence can effectively activate traditional photosensitizer, which has a strong absorbance at UV–vis regions. An UCNP-activated photodynamic DNA-based nanosystem was developed for spatiotemporal control of gene expression using NIR light. The system comprised a photodynamic module, enzyme-cleavable antisense oligonucleotides, and a mitochondria localization signal to induce mitochondrial damage and enzyme translocation. NIR light triggered ROS generation to induce sequence-specific gene knockdown via enzyme-activated oligonucleotide cleavage. This targeted mitochondrial photodamage and programmable gene regulation enhanced antitumor efficacy (Fig. S2b in Supporting information) [37]. This highlights the challenge of activating photosensitizers in deep tissues or organs, which is crucial for broadening PDT applications. However, the NIR light could not thoroughly penetrate the body as X-rays. X-rays possess higher energy that would cause damage to normal tissues.

Self-illuminant systems, such as bioluminescence or chemiluminescent molecules, can emit light energy without outside radiation to active PDT. Bioluminescence and chemiluminescent systems depend heavily on surrounding substrates, limiting their in vivo applications. Persistent luminescence nanoparticles (PLNPs) can emit luminescence steadily for hours or days without substrates, thus acting as efficient self-illuminance for PDT. Zhao et al. developed an energy-storing PLNPs containing DNA nanocomplex, enabling the tumor site glutathione (GSH)-triggered PDT of breast cancer without needing an external laser. The DNA nanocomplex was assembled with an AS1411-aptamer encoded ultralong single-stranded DNA chain as a scaffold, which allows photosensitizer loading and nucleolin-mediated tumor cell recognition. PLNPs were radiated to store energy and then coated with a MnO2 shell to prevent energy degradation. Upon the GSH-rich tumor cell, the MnO2 shell decomposed to release Mn2+ to catalyze O2 production for PDT. Then PLNPs were exposed to act as self-illuminants to trigger SiPcCl2, converting the produced O2 into cytotoxic 1O2. The PLNP-based PDT nanosystem synergistically induced oxidative stress and apoptosis through a GSH-triggered self-illuminating mechanism without external stimulation (Fig. S2c in Supporting information) [38].

2.3. Construction of DNA-based CDT nanosystemCDT is a therapeutic strategy that utilizes metal ions to catalyze the generation of reactive species, such as free radicals, thereby inducing cell death. DNA can form complexes with different metal ions, enabling the construction of a DNA-based CDT nanosystem. Metal ions, such as iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), and cerium (Ce), can be incorporated into DNA structures, acting as catalysts to start Fenton or Fenton-like reactions. DNA-based CDT nanosystem catalytically transforms hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into highly reactive hydroxyl radicals, inducing potent cytotoxicity to induce cancer therapy. The Fenton reaction catalyzes the interaction between iron and H2O2 to produce •OH [2]. Henry J. Fenton first described this mechanism in the late 19th century. The mechanism is summarized by the equation: Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + OH− + •OH. Ferrous iron (Fe2+) reacts with H2O2 to catalyze the generation of ferric iron (Fe3+), a hydroxide ion (OH−), and •OH. The hydroxyl radicals are highly reactive to prompt second-order reactions of oxidative degradation of organic compounds. By virtue of the capacity to degrade organic pollutants, Fenton reaction is extensively used in wastewater and other environmental remediation procedures. Fenton reaction is also involved in metabolic processes in organisms and can induce oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage, accelerated aging, and potential for disease treatment. Wei et al. designed a promising nanosystem for CDT through the Fenton reaction. Ferrocene complexes were conjugated to nanocrystals via pH-responsive DNA linkers. These DNA strands facilitated acidity-induced crosslinking, intensifying ferrocene accumulation within the tumor microenvironment. Ferrocene complexes catalyzed the cytotoxic Fenton reaction within tumor cells, enabling on-demand activation of ferrocene toxicity. The nanocrystal cores were designed to realize that UV light triggered the cleavage of photocleavable PEG chains, allowing for the shielding of healthy tissues while specifically enabling CDT at tumor sites (Fig. S3a in Supporting information) [39]. Integrating inorganic nanomaterials with DNA nanoengineering inspired by biological systems holds promise for the rational design of advanced theranostic systems.

Manganese-based Fenton-like reactions are promising alternative to traditional Fenton reactions for environmental remediation and therapeutic applications. Fenton-like reaction refers to metal catalyst other than iron, such as manganese (Mn), to generate hydroxyl radicals from H2O2: Mn2+ + H2O2 → Mn3+ + OH− + •OH. The manganese catalyst reacts with H2O2 to form the highly reactive •OH. As a traditional Fenton reaction, hydroxyl radicals engage in secondary reactions that can lead to the oxidative degradation of organic compounds. Manganese-based Fenton-like reactions are more efficient under neutral or mildly primary conditions than traditional Fenton reactions, which require acidic conditions. This property makes them particularly useful in environmental applications, such as degrading organic pollutants in wastewater. Furthermore, manganese-based Fenton-like reactions have shown promise in therapeutic applications, like cancer treatment, where they can generate cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals within tumor cells. Meng et al. utilized DNA as a template for in-situ DNA functionalized biomineralization of MnO2, demonstrating distinct biological performances from MnO2 adsorbed with DNA after modification. The poly-T DNA exhibited high biological stability, facilitating the rational design of DNA templates for targeted delivery and multimodal tumor therapy. MnO2 formed a hybrid structure that consists of cubes or sheets, depending on the concentration of DNA templates. This hybrid structure was beneficial for binding DNA to MnO2, providing new insights into DNA biointerface (Fig. S3b in Supporting information) [40]. Li et al. developed a DNA-based nanosystem that utilized an amphipathic telluroether to coordinate with Mn2+ and assembled with cholesterol-modified DNA to form a nano micelle. By utilizing the telluroether's excellent electron-donating capability, the Mn2+-based Fenton-like reaction accelerated the production of excessive ROS in cancer cells. The surface of nano micelle was designed to initiate a hybridization chain reaction (C-HCR) of two designer DNA hairpins, forming a DNA network outside the nano micelle. The nanosystem demonstrated significant tumor growth suppression in gene/chemo-dynamic therapy (Fig. S3c in Supporting information) [41].

Copper-based Fenton-like reactions offer a promising alternative to traditional Fenton reactions. In these reactions, copper (Cu2+) serves as the catalyst, producing hydroxyl radicals from H2O2. The reaction is expressed as follows: Cu2+ + H2O2 → Cu+ + OH− + •OH. Like the traditional Fenton reaction, the copper-based Fenton-like reaction produces highly reactive hydroxyl radicals that can degrade organic compounds. This can aid in pollution remediation or eliminating harmful cells within the body. Li et al. demonstrated a design of aptamer-functionalized nanoclusters, utilizing the versatility and programmability of functional nucleic acids to improve targeting and therapy efficacy. After entering cells, the nanoclusters underwent oxidation, driving a pH-independent Fenton-like reaction producing ROS, involving the generation of Cu+ and Cu2+ ions. Concurrently, Cu2+ ions reacted with GSH antioxidants, depleting and producing additional Cu+ ions to stimulate the Fenton-like reaction, further amplifying oxidative damage. In vivo tests showed potent anti-tumor effects with excellent biocompatibility, signifying the potential of copper-based Fenton-like reactions in creating an intelligent theranostic system (Fig. S3d in Supporting information) [42]. Yu et al. designed a nano-cascade system that employed the power of Cu+ and DNAzyme to combat cancer. The system worked by depositing cuprous oxide on ZIF-8 to provide Cu+ for catalysis and induce cuproptosis. DNA was adsorbed electrostatically and released in tumor cells as DNA, zinc ions, and Cu+. The combination of DNA and zinc ions leaded to the formation of a DNA enzyme that specifically recognized and cleaved CAT RNA, accumulating H2O2. Cu+ triggers the Fenton-like reaction to produce ROS for gene silencing and cell death. Cu2+, produced by the Fenton-like reaction, reacted with intracellular GSH, and was transformed into Cu+. Cu+ not only induces CDT but also leads to cuproptosis (Fig. S3e in Supporting information) [43].

The Ag+-mediated Fenton-like chemistry uses silver ions (Ag+) to facilitate Fenton-like reactions. Fenton reactions typically involve the interaction of H2O2 and ferrous ions to produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals. However, their implementation needs improvement due to the requirement of ferrous ions and a narrow pH range. On the other hand, using silver ions in Ag+-mediated Fenton-like reactions increases the applicable pH range and enhances the efficiency and yield of hydroxyl radicals. These silver ions catalyze the decomposition of H2O2, like ferrous ions, generating hydroxyl radicals. Tang and colleagues developed a DNA-silver nanoclusters-based DNA tetrahedral nanoprobe for CDT and gene silencing. The bifurcated sgc8 aptamers incorporated in the DNA nanoprobe utilize multivalent effects, thus efficiently targeting and delivering them explicitly into tumor cells. The significance of DNA-silver nanoclusters was their ability to react with H2O2 in the Ag+-mediated Fenton-like reactions, thereby generating cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals. The DNA nanostructure's programmable modularity facilitated the silver nanoclusters' precise spatial orientation, allowing controlled chemodynamic responses in the presence of intracellular H2O2. This sophisticated nanodevice combined silver-mediated Fenton-like chemistry and gene therapy, inducing cancer cell apoptosis while mitigating toxicity implications on healthy cells [44].

Cerium, a rare earth element, has the potential to regulate ROS through its ability to exist in both +3 and +4 oxidation states. This unique redox behavior allows for an oxidation–reduction cycle that effectively scavenges ROS, including harmful free radicals. These capabilities have promising applications in therapeutic interventions for health and disease management. Yao et al. has shown that a DNA-ceria nanocomplex could assemble into artificial peroxisomes within cells to regulate ROS. This breakthrough innovation utilized pH-responsive DNA nanostructures to trigger intracellular aggregation. The nanoscale complex efficiently entered cells, and the endo lysosomal acidity-induced assembly into microscale artificial organelles enhanced cellular retention. The ceria component provided enzyme-like catalase activity, effectively decomposing H2O2 to prevent redox imbalance and oxidative stress [45].

Zinc (Zn) plays a crucial role in maintaining redox homeostasis, and any imbalance can elicit significant production of ROS in biological systems. This essential trace element is prevalent in multiple physiological operations, including growth, development, and manifold cellular functions. Yet, excessive levels can ignite ROS production, thereby instigating oxidative stress. Zinc can stimulate ROS generation via numerous pathways, predominantly the Fenton reaction. In this reaction, free or non-attached zinc propels the conversion of H2O2 into superoxide and hydroxyl radicals-highly reactive species that induce oxidative damage. Such a Fenton-like chemistry relies profoundly on Zn's redox activity, mainly when it is imbalanced or overloaded. Zinc's propensity to interfere with the mitochondrial electron transport chain may also amplify ROS production. An overabundance of zinc can trigger mitochondrial dysfunction, leading to altered oxygen consumption and boosted ROS generation. This led to the development of ZIF-8, designed to simultaneously deliver microRNA and performed zinc-based CDT. ZIF-8′s high porosity enabled efficient loading and protection of miR-34a. An acidic tumor environment stimulated the disintegration of the nucleic acid drugs and the simultaneous release of miRNA. Simultaneously, Zn2+ ions accelerated the generation of ROS via Fenton-like reactions, laying the groundwork for CDT [46].

Carbon dots (CDs) are a type of fluorescent nanomaterial that possess biocompatibility, low toxicity, and customizable fluorescence. They can generate ROS when exposed to light. Due to their catalytic activities, CDs show great potential in environmental remediation and biomedicine applications. Li et al. demonstrated the fabrication of artificial enzymatic mimics by creating carbon dots derived from natural biomolecular precursors. Four types of dots were synthesized from RNA nucleosides, only the uridine-derived U-CDs demonstrated enzymatic activity, producing singlet oxygen and prompting DNA strand breaks. U-CDs intercalated within the DNA structure utilizing their surface quinone groups to orchestrate an oxidative Fenton-like reaction. This reaction converted oxygen into H2O2 and hydroxyl radicals, causing the separation of supercoiled DNA. This unique property of mimicking oxidative enzymes highlighted the potential of nanomaterials created using biological components [47]. Zhang et al. synthesized a series of nitrogen-doped carbon dots (C-dots) that are cost-effective and stable photosensitizers. Compared to molecular photosensitizers, these C-dots showed the highest activity, and they can accomplish oxidation reactions in a few seconds. Due to their excellent photosensitized oxygen activation, these water-soluble C-dots are a promising oxidase-mimicking nanozyme for photodynamic antimicrobial chemotherapy and other applications [48]. Ge et al. synthesized a new agent for PDT that is based on graphene quantum dots (GQDs). This GQDs can produce 1O2 through a multistate sensitization process, resulting in a quantum yield of 1.3, which is the highest yield reported so far among PDT agents. In vitro and in vivo studies showed that GQDs were as highly efficient PDT agents while also providing imaging capabilities. GQDs represent a new class of PDT agents that offer superior performance compared to traditional agents, in terms of 1O2 quantum yield, water dispersibility, photo-stability, pH-stability, and biocompatibility [49]. Zhang et al. discovered that the ROS generated can induce further oxidation and growth of C-dots, which leads to visible light absorption (400–650 nm) and extended fluorescence emission from blue to green. Light-treated C-dots exhibit higher peroxidase and oxidase-like activity than untreated ones. Their catalytic efficiency is 11 times higher when exposed to visible light, promising as PDT agent for cancer therapy [50].

3. Applications of CDT 3.1. Redox homeostasis regulationROS are crucial signaling molecules in cellular metabolism, primarily produced as by-products of enzymatic reactions. The intracellular levels of ROS are maintained by a dynamic equilibrium between production and scavenging processes. If this balance is disturbed, oxidative stress occurs, which is closely linked to the development and progression of several diseases, including cancer, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions. Various organelles, such as the cytoplasm, endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria, and peroxisomes, work together to maintain intracellular ROS homeostasis. Peroxisomes act as multifunctional organelles in all eukaryotic cells, housing redox enzymes responsible for ROS elimination. Due to dysfunctional organelles, excessive ROS production or impaired scavenging ability can lead to cellular damage. Introducing artificial organelles, such as peroxisome analogs or substitutes, holds promise in mitigating ROS-induced damage in cells with imbalanced ROS levels. Yao et al. developed a dynamic assembly system that utilizes DNA-ceria nanocomplexes to construct artificial peroxisomes (AP) within cells. The nanocomplex was synthesized using branched DNA with an i-motif structure that responds to the acidic lysosomal environment, triggering transformation from a nanoscale system into a larger-scale AP. The initial nanoscale form facilitated efficient cellular uptake, while the larger-scale AP ensured cellular retention. The AP acted as a ROS eliminator by exhibiting enzyme-like catalytic activities that decomposed H2O2 into O2 and H2O. Thus, regulated intracellular ROS levels within living cells, preventing excessive GSH consumption and maintaining redox homeostasis. Under oxidative stress, AP preserved cytoskeleton integrity, mitochondrial membrane potential, calcium concentration, and ATPase activity, sustaining the energy required for cell migration. Consequently, the AP inhibited cell apoptosis and reduces cell mortality through ROS elimination (Fig. 3a) [45].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Intracellular redox homeostasis regulation. (a) Intracellular lysosomal acidic condition-induced assembly of DCNC into artificial peroxisome and ROS regulation. Reprinted with permission [45]. Copyright 2022, Springer Nature. (b) ZIFs@Dz mediated ROS regulation for tumor therapy. Reprinted with permission [51]. Copyright 2020, John Wiley and Sons. | |

Maintaining cellular redox homeostasis is vital for normal physiological processes, ensuring a balance between oxidized and reduced states. Hypoxic tumors have heightened antioxidant defenses, including activated antioxidant enzymes and intracellular redox buffer systems such as GSH. Disrupting the redox homeostasis was a potential strategy to increase the vulnerability of tumor cells to further ROS damage induced by external substances. One way to achieve this is by regulating the intracellular oxidation or reduction state. For instance, depleting GSH through nanovehicles or manipulating endogenous oxidants and antioxidants simultaneously can be effective [52]. Such an approach has the potential to break the redox homeostasis and reduce the tolerance of hypoxic tumors to ROS-mediated therapy. Li et al. proposed a strategy based on a nanoplatform called FeCysPW@ZIF-82@CAT Dz, which could disrupt redox homeostasis and enhance ROS-mediated hypoxic tumor therapy. The platform utilized a catalase DNAzyme (CAT Dz) loaded zeolitic imidazole framework-8 shell to cause redox dyshomeostasis). The CAT Dz degraded into Zn2+ cofactors, leading to CAT silencing for GSH depletion. In turn, caused RDH and H2O2 accumulation in tumor cells, reducing resistance to ROS and effectively eliminating through CDT induced by FeCysPW. In vitro and in vivo experiments shown that pH/hypoxia/H2O2 triple-stimuli responsive nanocomposite effectively eradicated hypoxic tumors. The RDH strategy opened up new possibilities for ROS-mediated treatment of hypoxic tumors (Fig. 3b) [51].

3.2. Combined diagnosis and therapyTheranostic nanoplatforms are popular area of research due to their ability to integrate therapy and diagnostics. Traditional tumor therapies such as chemotherapy, surgery, and radiotherapy have limitations, such as drug resistance, side effects, and lack of specificity. PDT is an efficient antitumor strategy that triggers the production 1O2 through photosensitization reactions with molecular oxygen. CDT is another therapy that uses Fenton and Fenton-like reactions to generate cytotoxic hydroxyl radicals by breaking down endogenous H2O2 while minimizing damage to normal tissues. MnO2 nanosheets are biocompatible structures that adsorb DNA strands through physisorption, bonding the DNA phosphate backbone and MnO2. MnO2 nanosheets are widely used for biomarker monitoring and intracellular imaging. MnO2 nanosheets exhibits catalase-like activity that converts H2O2 into O2, improving hypoxic tumor microenvironments and boosting oxygen-dependent PDT. In elevated GSH levels, MnO2 nanosheets can be reduced to Mn2+, acting as a CDT agent through Fenton-like reactions. The consumption of GSH further enhances the efficacy of CDT. Cheng et al. developed a MnO2 nanosheet-based probe that could detect two types of miRNAs (miR-21 and miR-155), target cancer cells precisely, and offered a synergistic effect for CDT/PDT therapy. The probe could anchor the complex formed by miRNA-recognizing probe R and an AS1411 aptamer on the MnO2 NS surface, which allowed for simultaneous miRNA recognition, cancer cell targeting, and photosensitizer loading. The probe could reduce false-positive signals by using aptamer recognition, GSH-responsive miRNA signal amplification, and dual detection, which increases miRNA imaging accuracy. The probe utilized the catalase-like activity and GSH depletion capability of MnO2 nanosheets, the Fenton-like effect of Mn2+, and the singlet oxygen produced by the photosensitizer TMPyP4 to offer an enhanced synergistic effect for CDT/PDT therapy. The probe was a highly effective therapeutic platform for cancer treatment that offers precise targeting, simultaneous detection, and synergistic therapy (Fig. 4a) [53].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystem for combined diagnosis and therapy. (a) Detecting dual microRNAs that target cancer cells and enhancing synergistic therapy using CDT/PDT. Reprinted with permission [53]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (b) Nanodevice with AND logic gating for cascaded signal amplification of miRNA-21 (fluorescence imaging) and GSH-activated MR imaging-guided theranostics MnO2@PEI-IAA. Reprinted with permission [54]. Copyright 2019, John Wiley and Sons. | |

DNA probes have been getting much attention lately for their ability to detect biomolecules like RNAs and proteins. Scientists have used nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles, graphene oxide, and liposomes to help these probes get inside living cells more efficiently. MiRNAs are non-coding RNA that are very useful for diagnosing cancer, and researchers have been studying them extensively as detection targets. While some DNA nanodevices have shown promise for detecting and profiling miRNAs, they often lack tumor responsiveness, involve complex sequence design and optimization, and lack amplification specificity, leading to false-positive results. Developing a DNA nanodevice that is smart, tumor-specific, and has signal amplification is still a challenge. Yan et al. presented a smart DNA nanodevice that uses AND logic-gated on MnO2 nanosheets for tumor-specific GSH-activated theranostics. This design allowed for amplified fluorescence signaling and magnetic resonance imaging, specifically in tumor cells with overexpression of microRNA-21 and GSH. The nanodevice avoided false-positive background signals in normal cells. Guided by dual-mode profiling, the nanodevice generated hydroxyl radicals for CDT, relieved hypoxia by producing oxygen, and depleted glucose. In vivo studies demonstrated sensitive tumor detection and effective therapeutic outcomes. This rationally engineered nanosystem integrated programmed selectivity and cooperativity between multiple modalities, including imaging, CDT, oxygenation, and starvation effects. This approach highlighted the potential of combining DNA nanotechnology with nanomaterials to develop precision nano theranostic that respond accurately to biological inputs (Fig. 4b) [54].

4. Applications of PDT 4.1. Photoactivated drug releasePDT is a promising cancer treatment that uses photosensitizers to generate ROS upon light irradiation. ROS causes oxidative damage to cancer cells, triggers apoptosis, and breaks organic molecules to trigger drug release. Shi et al. developed a new approach to control the release of nucleic acid therapeutics from DNA nanoflowers using light. This method had the potential for better spatiotemporal control in cancer treatment. The DNA nanoflowers were loaded with Ce6-labeled cDNA (Ce6-cDNA), which acted as a tumor-targeting photosensitizer delivery carrier and a gene therapeutic cargo. Under spatiotemporal laser irradiation, the ROS was generated to induce a self-disassembly process. Tumor cells could efficiently disassemble DNA nanoflowers when exposed to light, allowing more DNAzymes to perform amplified gene silencing. The inhibition of ATG5 mRNA expression suppressed autophagy in tumor cells, enhancing the antitumor effect of low-dose PDT in vitro and in vivo. In animal experiments, the dose of Ce6 used was 100 times lower than the generally applied Ce6 dose. The DNA nanoflowers was a multifunctional system highly compatible with biological systems, had low potential for causing immune reactions, and was very efficient. It provided magnesium ion co-factors for DNAzymes. The system was designed to disassemble itself when activated by light, thus overcoming the limitations of oligonucleotide drugs delivered by DNA nanostructures. This approach could potentially improve the therapeutic efficacy of low-dose PDT by suppressing cellular autophagy (Fig. 5a) [55]. DNA nanocarriers have been developed to deliver immunomodulators like CpG oligodeoxynucleotides and anti-PD1 antibodies to tumors. This approach is more effective in treating tumors with less toxicity than using free CpG and anti-PD1. DNA immunomodulators are a promising alternative to PD1/PDL1 antibodies because of their stability, low cost, and ease of modification. DNA sequences can self-assemble into nanostructures to facilitate tumor-targeted delivery. Some strategies induce intracellular release through Fenton reactions utilizing metal-containing analogs or lysosomal acidity. Wang et al. proposed a photo-controlled DNA nanomedicine to activate tumor immune responses precisely. The system used a circular DNA template that integrates anti-PDL1 aptamer, CpG, and G-quadruplex motifs for RCA, generating an aptamer/CpG-functionalized DNA nanoflower loaded with porphyrin photosensitizer TMPyP4. Laser activation at tumor sites generated ROS, fracturing membranes, and releasing immunomodulators to synergistically enhance photodynamic immunotherapy in melanoma models. This precisely tunable system held the potential to co-deliver agents while reducing off-target toxicity (Fig. 5b) [56].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. DNA-based PDT nanosystem for drug release. (a) Photoactivated self-disassembly of multifunctional DNA nanoflower for amplified autophagy suppression for low-dose PDT. Reprinted with permission [55]. Copyright 2021, John Wiley and Sons. (b) Photocontrolled spatiotemporal delivery of PDL1 aptamers and CpG for enhanced tumor membrane-targeted photodynamic immunotherapy. Reprinted with permission [56]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. | |

Accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of cancer are crucial for improving patient outcomes. It is essential to monitor changes in tumor-related biomarkers in real-time during tumor progression in order to understand the mechanisms underlying tumorigenesis and guide precise therapy. However, developing nanoplatforms that can co-deliver therapeutic and imaging agents is a significant challenge. Many tumors cannot be eradicated with single treatments due to cancer's intrinsic complexity and high metastatic potential. Although there has been considerable progress in expanding anti-cancer modalities, numerous tumor types require multifaceted approaches. For example, chemotherapy is commonly used but often met with multidrug resistance and toxicity. Recently, researchers have been exploring multimodal synergistic therapies that combine various approaches. Unlike individual treatments, multimodal strategies maintain benefits while minimizing side effects, significantly improving therapeutic impact. Yu et al. designed a multifunctional aptamer-DNA-gold nanoparticles machine for targeted multimodal breast cancer synergistic therapy and real-time tumor progression monitoring. The Apt-DNA-Au nanomachine utilized entropy-driven DNA strand displacement and consists of three modules: a Cy5-labeled DNA hybrid (A/C/D) formed by hybridizing strands A and C with antisense DNA-incorporated D, and single-stranded fuel DNA (F/D) (Fig. S4a in Supporting information) [57].

The current mainstream cancer management techniques have certain drawbacks, such as radiation exposure during procedures, high costs, and overdose during radiotherapy. Targeted imaging is a promising approach that focuses on the interaction between ligands and receptors on the surface of cancer cells with overexpressed receptors. The oligonucleotide aptamer AS1411 targets the tumor-specific diagnostic marker nucleolin selectively and has demonstrated antitumor activity and safety in clinical trials. An autonomous self-assembling nanodevice that enables in-situ generation could overcome limitations in identifying cancerous cells and targeted drug delivery while retaining tumor-targeting capabilities. Jou et al. used DNA nanotechnology to detect genetic sequences in vitro. The hybridization chain reaction amplified the signal by generating intracellular polymer wires composed of Zn(Ⅱ)-protoporphyrin IX intercalated G-quadruplexes upon nucleolin receptor/AS1411 aptamer complex activation at malignant cell surfaces. Zn(Ⅱ)-protoporphyrin IX units exhibited enhanced fluorescence relative to the free metal complex, enabling effective tumor imaging. Additionally, the cooperative cytotoxic effects of Zn(Ⅱ)-protoporphyrin IX and photodynamic properties within the polymer chains provided multifaceted therapeutic benefits for cancer treatment through this targeted platform (Fig. S4b in Supporting information) [58].

Surgical resection is the primary treatment for solid tumors but has limitations that can cause recurrent tumors and metastasis. Current diagnostic approaches may miss recurrence, and postoperative treatments have low response rates and can damage healthy tissues. Detecting malignant tumor recurrence mainly relies on imaging examinations and monitoring tumor biomarkers, but these methods have limitations. In situ, enrichment of tumor cells facilitates earlier recurrence detection, while capturing and eliminating tumor cells in situ would be of significant value for controlling metastasis. Wang et al. developed an innovative postoperative DNA hydrogel to overcome existing limitations by integrating diagnostics and treatment. The hydrogel contained PDL1 aptamers that detected and accumulated early relapsed tumor cells, which increased local ATP levels and triggered a circular ATP sensor to issue an early warning. The hydrogel also included Ce6 photosensitizer and CpG immune adjuvant, which generated PDT-generated ROS upon laser activation to damage the captured cells. This led to the release of antigens, essential for immune activation. The DNA hydrogel fractured, releasing PDL1 aptamers and CpG, leading to checkpoint blockade and immune activation for systemic antitumor immunotherapy. The hydrogel provided a recurrence monitoring system, concentrating tumor cells for spatiotemporally controlled photodynamic immunotherapy and recurrence and metastasis prevention (Fig. S4c in Supporting information) [59].

4.3. Strategies to promote PDTAn innovative approach to treating early-stage cancer using microRNA-triggered PDT facilitated by an engineered nucleic acid amplifier was proposed by Zhang et al. The system comprised UCNPs connected to photo-caged DNA nanocombs containing photosensitizers and protected hairpins. When exposed to NIR radiation, the photocages were cleaved, revealing sites for microRNA-mediated hybridization cascades that activated the photosensitizers. This mechanism allowed spatiotemporal control over ROS generation, enabling highly precise PDT. In addition, this system was highly sensitive to low levels of microRNA, often detected in early-stage tumors, while reducing off-target effects. In vivo experiments confirmed the efficacy of this approach in suppressing tumors. Combining UCNPs with programmable, photocaged DNA nanostructures enabled NIR-controlled amplification and scoped PDT, even with minimal early-stage biomarkers. This study underlined the potential of integrating photonic nanomaterials and nucleic acids to create responsive, precision-guided nanotheranostic. The design employed a photo-caged DNA nanocomb attached to core-shell UCNPs, which respond to NIR light, producing blue light and generating ROS. This innovative design layed the foundation for new early-stage cancer therapies by unlocking the potential of NIR-switched microRNA amplifiers (Fig. S5a in Supporting information) [60].

Pang et al. proposed to create intelligent nanomachines to help target specific tumors more accurately during PDT. These down/upconversion nanomachines were designed to modify photosensitizer DNA logic circuits presented on down/up conversion nanoparticles (D/UCNPs). The DNA circuits followed "AND" logic computations, where the dual-gated inputs were tumor-associated GSH and thymidine kinase 1 mRNA. This design utilized toehold-mediated strand displacement (TMSD) to activate enzymatic-free quenching of D/UCNPs, leading to more efficient and precise activation of the NIR-triggered PDT nanosystem. The emission processed that restored the upconversion in D/UCNPs could start the photosensitizer Ce6. This leaded to the generation of singlet oxygen, which was a logical outcome. The fluorescence resulting from down-conversion in D/UCNPs in the NIR-II window helped visualize the positioning of D/UCNMs inside the body. Inspired by biology, the proposed design used an intelligent DNA circuit integrating redox-cleavage double-stranded DNA probes and TMSD-related double-strand DNA probes. This design provided the features of 'AND' logic computation, enzyme-free amplification, and activatable PDT, which significantly improved the precision and effectiveness of tumor therapy. Using D/UCNMs in PDT presented new opportunities for combination therapies and innovative vaccine development (Fig. S5b in Supporting information) [61].

PDT can be more effective when targeted at specific organelles, especially the mitochondria. However, organisms have natural defense mechanisms that can make them resistant to PDT. APE1, a DNA repair enzyme, has anti-apoptotic functions, and its subcellular localization can affect PDT's effectiveness. DNA-based probes can detect and image a broad range of targets. Light-activatable DNA sensors have recently been developed to profile enzyme activity within specific organelles. Yu et al. developed a versatile nanoplatform (UR-HAPT) that combined nano photosensitizers based on UCNP, a mitochondria-targeting strategy, and a DNA reporter for real-time imaging of subcellular APE1 dynamics in response to NIR light-triggered, mitochondrial-localized PDT. The UR-HAPT comprised four essential elements: a UCNP light transducer, rose bengal photosensitizer, triphenyl phosphonium mitochondrial-targeting ligand, and a DNA-based fluorescent probe for detecting APE1 activity. This design potentially linked the fields of PDT and DNA biosensing to enable subcellular molecular imaging during therapeutic interventions (Fig. S5c in Supporting information) [62].

Light can control chemical and biological processes non-invasively, but UV/visible light is often used, with low tissue penetrance and potential harm. To overcome this, UCNPs doped with lanthanide ions are used as light transducers, converting NIR photons into UV/visible light, penetrating tissues. UCNPs enable NIR light-controlled regulation of neural activity and tumor treatment. UCNPs have been integrated with DNA design for biomedical applications. Chen et al. developed a UCNP-based NIR light-regulated tumor targeting strategy to improve PDT efficacy, a nanoplatform for enhanced gene silencing cancer therapy, which was controlled by NIR light. The platform combined therapeutic DNAzymes with upconversion nanotechnology. The therapeutic agent used in this design was a 10–23 DNAzyme targeting survivin mRNA. The nanoplatform, called "UP-Dz" was constructed by coating UCNPs with Rose Bengal photosensitizer-conjugated poly (ethylene imine). Then, DNAzymes were loaded onto the nanoplatform using electrostatics. Once the nanoplatform entered the cells and was trapped in the endosome, NIR irradiation caused the UP-Dz to generate ROS, disrupting the endosomal membranes and allowing for the improved cytosolic release of DNAzymes. This caused survivin mRNA silencing and downregulation of survivin protein expression, promoting tumor cell apoptosis. The platform combines DNAzyme-based gene therapy with a PDT effector, triggered by NIR light, for a combined cancer treatment (Fig. S5d in Supporting information) [63].

5. Challenges and opportunitiesDNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems have emerged as a promising technology in DNA biotechnology. These generators involve the controlled production of ROS in a desired fashion using engineered DNA structures. Despite their potential, several major challenges still need to be addressed to ensure their applications. (i) Precise control and safety: Achieving precise control over the production of ROS is essential. Uncontrolled ROS generation could lead to cellular damage and oxidative stress, impacting the overall health of biological systems. (ii) Targeted delivery is crucial for ROS therapy, but selectively delivering ROS to specific cells in vivo disease sites is challenging. A significant hurdle is developing strategies to ensure ROS reaches its intended target disease site without harming healthy tissue cells. (iii) Biocompatibility in vivo is crucial for DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems to integrate effectively into biological systems. Ensuring that the materials used in constructing these generators do not trigger any adverse immune responses or toxicity is essential.

Nanomedicine has shown great interest in developing nanosystems capable of generating ROS due to their potential applications in targeted therapies and diagnostics. DNA-based nanosystems have emerged as promising candidates for ROS generation among the various nanomaterials explored. This discussion focuses on the advantages of using DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems and their crucial role in advancing nanomedicine. DNA-based nanosystems offer numerous benefits in generating targeted ROS. These nanosystems can be precisely designed and controlled to produce specific types of ROS and prevent their release kinetics. DNA is biocompatible and biodegradable, ensuring greater safety for in vivo applications. DNA-based nanosystems can be modified with specific targeting moieties to enhance therapeutic efficacy by minimizing off-target effects and maximizing ROS generation at the intended location. Additionally, ROS release can be precisely controlled within the target cells or tissues. DNA-based nanosystems can be easily combined with other therapeutic modalities to enhance therapeutic outcomes in nanomedicine.

Opportunities: (ⅰ) Therapeutic applications: DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems hold promise for therapeutic interventions, particularly in conditions to controll ROS production, such as cancer treatment, sonodynamic therapy (SDT). (ⅱ) Antimicrobial strategies: DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems could be utilized to develop innovative antimicrobial strategies. (ⅲ) Cell signaling studies: By precisely regulating ROS production, researchers can further understand cellular signaling pathways that involve oxidative stress, providing insight into various physiological and pathological processes. (ⅳ) DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems might find applications in bioremediation, assisting in removing pollutants and contaminants from the environment by promoting oxidative degradation. (ⅴ) DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems could be harnessed to develop advanced materials for nanotechnology and material science applications.

6. Conclusion and outlookIn conclusion, DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems are promising nanomedicine by the design of regulation of intracellular redox homeostasis. The nanosystems were explored for drug delivery, served as active antitumor agents, and can be used to construct PDT or CDT synergistic systems and develop high-performance antitumor derivatives. DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystems stand at the intersection of innovative biotechnology with potential impacts on medicine, the environment, and materials science. Addressing control, safety, and delivery challenges while capitalizing on opportunities in therapeutics and environmental solutions will shape the trajectory of this emerging field. Although investigations are still in the early stages and several challenges remain to be resolved, we believe the DNA-based ROS-generating nanosystem will innovate clinical disease treatment under the conjoint efforts of researchers from different fields.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2022YFC2603800) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22274113).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.109637.

| [1] |

M. Valko, C.J. Rhodes, J. Moncol, et al., Chemico-Biological Interact. 160 (2006) 1-40. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2005.12.009 |

| [2] |

S. Bhattacharya, Free Radic. Hum. Health Dis. 2 (2015) 17-29. |

| [3] |

J. Boonstra, J.A. Post, Gene 337 (2004) 1-13. DOI:10.1016/j.gene.2004.04.032 |

| [4] |

M. Al Shahrani, S. Heales, I. Hargreaves, M. Orford, J. Clin. Med. 6 (2017) 100. DOI:10.3390/jcm6110100 |

| [5] |

Q. Liu, Y.J. Kim, G.B. Im, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (2020) 2008171. |

| [6] |

Y.T. Fan, T.J. Zhou, P.F. Cui, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1806708. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201806708 |

| [7] |

M. Zhang, Z. Dai, S. Theivendran, et al., Nano Today 36 (2021) 101035. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101035 |

| [8] |

Z. Zhang, R. Dalan, Z. Hu, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2202169. DOI:10.1002/adma.202202169 |

| [9] |

J. Zhang, Q. Jia, Z. Yue, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2200334. DOI:10.1002/adma.202200334 |

| [10] |

J. Noh, B. Kwon, E. Han, et al., Nat. Commun. 6 (2015) 6907. DOI:10.1038/ncomms7907 |

| [11] |

N. Singh, G.R. Sherin, G. Mugesh, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202301232. DOI:10.1002/anie.202301232 |

| [12] |

S.L. Li, P. Jiang, F.L. Jiang, Y. Liu, Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (2021) 2100243. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202100243 |

| [13] |

M. Karimi, P. Sahandi Zangabad, S. Baghaee-Ravari, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 4584-4610. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b08313 |

| [14] |

J. Wu, P. Ning, R. Gao, et al., Adv. Sci. 7 (2020) 1902933. DOI:10.1002/advs.201902933 |

| [15] |

J. Ouyang, Z. Tang, N. Farokhzad, et al., Nano Today 35 (2020) 100949. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100949 |

| [16] |

C.M. Niemeyer, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 36 (1997) 585-587. DOI:10.1002/anie.199705851 |

| [17] |

N.C. Seeman, Nature 421 (2003) 427-431. DOI:10.1038/nature01406 |

| [18] |

Y.H. Roh, R.C.H. Ruiz, S. Peng, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 40 (2011) 5730. DOI:10.1039/c1cs15162b |

| [19] |

S.L. Beaucage, R.P. Iyer, Tetrahedron 48 (1992) 2223-2311. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88752-4 |

| [20] |

J. Han, Y. Guo, H. Wang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 19486-19497. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c08888 |

| [21] |

D. Wang, J. Cui, M. Gan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 10114-10124. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c02438 |

| [22] |

M.R. Jones, N.C. Seeman, C.A. Mirkin, Science 347 (2015) 1260901. DOI:10.1126/science.1260901 |

| [23] |

A.D. Keefe, S. Pai, A. Ellington, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 9 (2010) 537-550. DOI:10.1038/nrd3141 |

| [24] |

Y. Guo, Q. Zhang, Q. Zhu, et al., Sci. Adv. 8 (2022) eabn2941. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.abn2941 |

| [25] |

M. Pan, Q. Jiang, J. Sun, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 1897-1905. DOI:10.1002/anie.201912574 |

| [26] |

C. Yao, H. Qi, X. Jia, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202113619. DOI:10.1002/anie.202113619 |

| [27] |

Z. Wang, J. Yang, G. Qin, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202204291. DOI:10.1002/anie.202204291 |

| [28] |

J. Sun, M. Pan, F. Liu, et al., ACS Mater. Lett. 2 (2020) 1606-1614. DOI:10.1021/acsmaterialslett.0c00445 |

| [29] |

C. Yao, R. Zhang, J. Tang, D. Yang, Nat. Protoc. 16 (2021) 5460-5483. DOI:10.1038/s41596-021-00621-2 |

| [30] |

H. Zhao, J. Lv, F. Li, et al., Biomaterials 268 (2021) 120591. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120591 |

| [31] |

P. Wang, M. Xiao, H. Pei, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 415 (2021) 129036. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129036 |

| [32] |

Y. Yuan, H. Zhao, Y. Guo, et al., Trans. Tianjin Univ. 26 (2020) 450-457. DOI:10.1007/s12209-020-00260-w |

| [33] |

K. Ni, T. Luo, G. Lan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 1108-1112. DOI:10.1002/anie.201911429 |

| [34] |

J. Liu, T. Zheng, Y. Tian, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 7757-7761. DOI:10.1002/anie.201902776 |

| [35] |

S.Y. Liu, Y. Xu, H. Yang, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2100849. DOI:10.1002/adma.202100849 |

| [36] |

G. Hong, A.L. Antaris, H. Dai, Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1 (2017) 0010. DOI:10.1038/s41551-016-0010 |

| [37] |

X. Chai, D. Yi, C. Sheng, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202217702. DOI:10.1002/anie.202217702 |

| [38] |

H. Zhao, L. Li, F. Li, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2109920. DOI:10.1002/adma.202109920 |

| [39] |

Z. Wei, Z. Chao, X. Zhang, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15 (2023) 11575-11585. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c22260 |

| [40] |

Y. Meng, J. Huang, J. Ding, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 637 (2023) 441-452. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2023.01.089 |

| [41] |

F. Li, Z. Lv, X. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 25557-25566. DOI:10.1002/anie.202111900 |

| [42] |

Q. Li, F. Wang, L. Shi, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 37280-37290. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c05944 |

| [43] |

Q. Yu, J. Zhou, Y. Liu, et al., Adv. Healthc. Mater. 12 (2023) 2301429. DOI:10.1002/adhm.202301429 |

| [44] |

Q. Tang, Q. Li, L. Shi, et al., Nanoscale Horiz. 8 (2023) 1106-1112. DOI:10.1039/D2NH00575A |

| [45] |

C. Yao, Y. Xu, J. Tang, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 7739. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-35472-2 |

| [46] |

H. Zhao, T. Li, C. Yao, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 6034-6042. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c21006 |

| [47] |

S. Li, F. Li, Y. Dong, et al., Small 18 (2022) 2106269. DOI:10.1002/smll.202106269 |

| [48] |

J. Zhang, X. Lu, D. Tang, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 40808-40814. DOI:10.1021/acsami.8b15318 |

| [49] |

J. Ge, M. Lan, B. Zhou, et al., Nat. Commun. 5 (2014) 4596. DOI:10.1038/ncomms5596 |

| [50] |

J. Zhang, Y. Lin, S. Wu, et al., Carbon 182 (2021) 537-544. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2021.06.053 |

| [51] |

Y. Li, P. Zhao, T. Gong, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 22537-22543. DOI:10.1002/anie.202003653 |

| [52] |

W. Zhang, J. Lu, X. Gao, et al., Angew. Chem. 130 (2018) 4985-4990. DOI:10.1002/ange.201710800 |

| [53] |

S. Cheng, Y. Shi, C. Su, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 214 (2022) 114550. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2022.114550 |

| [54] |

N. Yan, L. Lin, C. Xu, et al., Small 15 (2019) 1903016. DOI:10.1002/smll.201903016 |

| [55] |

J. Shi, D. Wang, Y. Ma, et al., Small 17 (2021) 2104722. DOI:10.1002/smll.202104722 |

| [56] |

D. Wang, J. Liu, J. Duan, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 44183-44198. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c12774 |

| [57] |

S. Yu, Y. Zhou, Y. Sun, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 5948-5958. DOI:10.1002/anie.202012801 |

| [58] |

A.F.J. Jou, Y.T. Chou, I. Willner, J.a.A. Ho, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 21673-21678. DOI:10.1002/anie.202106147 |

| [59] |

D. Wang, J. Liu, J. Duan, et al., Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 4511. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-40085-4 |

| [60] |

Y. Zhang, W. Chen, Y. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 21454-21459. DOI:10.1002/anie.202009263 |

| [61] |

L. Pang, X. Tang, L. Yao, et al., Chem. Sci. 14 (2023) 3070-3075. DOI:10.1039/D2SC06601G |

| [62] |

F. Yu, Y. Shao, X. Chai, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202203238. DOI:10.1002/anie.202203238 |

| [63] |

Y. Chen, R. Zhao, L. Li, Y. Zhao, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202206485. DOI:10.1002/anie.202206485 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35