b Zhixing Daohe (Jiangxi) Environmental Protection Industry Technology Research Institute Co., Ltd., Nanchang 330000, China;

c Engineering Research Center for Medicine, College of Pharmacy, Harbin University of Commerce, Harbin 150076, China

Nanomaterials (NMs) are considered excellent adsorbents and catalysts due to their large specific surface area, abundant surface-active sites, and specific surface chemistry [1], typically defined within the range of 1–100 nm [2-4]. The nanoscale particle size enables inherently inactive materials to achieve catalytic performance, while effective catalysts often displace higher efficiency [5,6]. Top-down and bottom-up methods are two main approaches to nanoparticle synthesis. Physical and chemical synthesis methods have been widely used, but they involve high energy consumption and the use of toxic reducing agents, stabilizers, and other solvents [7,8]. In contrast, microbial synthesis methods can mitigate many harmful effects, resulting in nanoparticles (NPs) with superior stability, dispersion, and biocompatibility [9,10]. In recent years, the biosynthesis of nanomaterials has attracted increasing attention on account of its cost-effectiveness, environmental friendliness, and ease of scale-up [11].

The microbial synthesis of nanomaterials can involve various biological entities such as bacteria, fungi, algae, viruses, or extracted biomolecules like proteins, polysaccharides, DNA, and short peptides [12-14]. These microorganisms and their metabolites are capable of synthesizing a wide range of metal nanoparticles (MNPs), including noble metals (e.g., Au, Ag and Pt) [15-17], metal oxides (e.g., ZnO and TiO2) [18,19], metal sulfides (e.g., PbS and CdS) [19,20], bimetallic/polymetallic nanoparticles (e.g., Pd-Au and Pd-Pt) [21,22], and other MNPs (e.g., PbCO3 and Zn3(PO4)2) [23,24]. However, it is important to note that wild-type microorganisms have limitations in terms of the variety and capacity of MNPs they can synthesize. The introduction of synthetic biology has opened up numerous possibilities in the field of metal nanomaterial biosynthesis. Genetic engineering of microorganisms has played an essential role in expanding the range of MNPs that can be biosynthesized, improving the tolerance limits of bacteria to environmental conditions, and increasing the productivity of uniform MNPs [25-28]. However, the characteristics of biosynthetic metal nanoparticles (bio-MNPs), the initiation and termination of the synthesis process, and even the composition of polymetallic NPs cannot be completely predicted or designed. Consequently, there is a growing focus on research aimed at achieving microbially controllable synthesis of MNPs through synthetic biology approaches.

According to the co-occurrence cluster analysis (Fig. 1), bio-MNPs have seen increasingly investigated in recent years, particularly in green synthesis and applications for wastewater treatment. In addition to degrading and removing of contaminants, some MNPs can also detect heavy metal ions in the solution as indicators [3]. After discharge into the environment, MNPs may lead to several toxic issues to other organisms. Machine learning (ML) can be applied to assess the safety of nanomaterials as an alternative to complex and expensive toxicological analysis [29]. Furthermore, ML can provide recommendations for designing of nanomaterial structures and properties through rapid predictive learning, but the guidance for directional modulation of bio-MNPs is still poorly explored [30].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Visual figures of co-occurrence cluster analysis using the keywords "microbial synthesis", "metal nanoparticles" and "environmental application". A total of 2597 relevant studies were screened from 2003 to June 2023 using Web of Science: (a) the keyword frequency and correlation; (b) the keyword timeline. The size of sphere represents research frequency, while the lines represent correlation. | |

In this review, a concise overview of current researches in microbial biosynthesis of metal nanomaterials is provided, with a focus on the role of synthetic biology in guiding and enhancing synthesis processes. And the targeted characterization techniques and significant potential value of machine learning are also explored. The present review aims to offer researchers interested in the synthesis and environmental applications of bio-MNPs a more comprehensive background and innovative ideas rooted in synthetic biology.

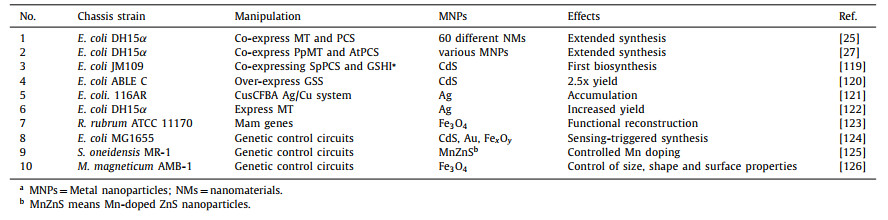

2. Conventional synthesis methods of nanomaterialsMacroscopically, the synthesis of metal nanomaterials can be categorized into two main approaches "top-down" and "bottom-up". Top-down methods involve reducing large metal structures into smaller nanoparticles through destructive physical or chemical processes. These methods typically disrupt the van der Waals forces between stacked crystal layers [1]. Examples of top-down synthesis techniques include machine grinding (or ball-milling) [31], laser ablation [32], sputtering [33], ion beam etching [34], and pyrolysis [35]. While top-down synthesis is relatively easier to perform, it may not be suitable for producing very small and uniform MNPs. For instance, after 70 h of grinding, the minimum particle size of coconut shell carbon powder can be reduced to as small as 4.32 nm [36]. Additionally, the polydispersity of colloidal noble metal nanoparticles often remains relatively large (σ > 10%) after laser [37].

Bottom-up approaches involve the assembly of atoms, ions, or smaller-scale particles into nanoparticles through the breaking and coupling of ionic or covalent bonds. Chemical deposition (gas and liquid phase) [38], electrochemical precipitation [39], sol-gel synthesis [40], spinning techniques [41], and biological synthesis [1], are included in the bottom-up approaches. While the aforementioned synthesis methods consume significant amounts of energy and contribute to carbon footprints, biosynthesis of MNPs is widely recognized for its environmental friendliness, biocompatibility, and cost-effectiveness [42]. Fig. 2 summarizes the different approaches for the synthesis of MNPs, offering a direct comparison of their advantages and disadvantages. Biological synthesis methods of MNPs contain highly compelling potential for further development.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Top-down and bottom-up approaches to the synthesis of MNPs. | |

Currently, various microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, microalgae, viruses and secreted biomolecules have been reported to synthesize a wide variety of MNPs with diverse types, morphologies, and particle sizes. A summary of typical wide-type microorganisms and the MNPs they have synthesized can be found in Table S1 (Supporting information). As shown in Table S1, wild-type microorganisms have demonstrated the capacity to synthesize different types of MNPs. However, within a single species, the morphology of the synthesized MNPs is often limited, and the range of particle sizes can be quite broad.

3.1. Microbial synthesis of MNPs 3.1.1. Biosynthesis mediated by bacteriaBacteria have received significant attention in the field of biological synthesis of nanomaterials due to their ease of isolation, survival, and cultivation. Currently, there are numerous bacterial genera have been reported to synthesize MNPs, including Bacillus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas, Klebsiella pneumonia, Actinobacillus and Lactobacillus [43]. It is known that bacteria can mediate the biosynthesis of a wide range of MNPs, such as Au, Ag, CuO, TiO2 and CdS NPs [44]. Furthermore, several extremophilic archaea have been reported to reduce and then accumulate MNPs. For instance, Haloferax sp. and Halogeometricum sp., can synthesize Ag NPs and Se NPs, respectively [45]. The thermophilic and acidophilic archaea Metallosphaera sedula and Sulfolobus tokadaii can separately synthesize W NPs and Pd NPs through redox processes [46,47].

3.1.2. Biosynthesis mediated by fungiFungi and yeasts offer unique advantages over prokaryotic microorganisms, such as high tolerance, bioaccumulation capability, and efficient metabolism for heavy metal ions [48,49]. The additional surface area provided by mycelium enhances the nucleation and conversion of metal ions kinetically, while extracellular enzymes facilitate the synthesis of predominantly extracellular MNPs [50,51]. Dozens of fungal strains, along with their filtrate containing reductases, have been shown to synthesize Ag NPs and Au NPs with varying size distributions [52-54]. Additionally, metal oxide NPs (e.g., ZnO, CuO, FexOy, ZrO2), and metal sulfide NPs (e.g., ZnS, PbS, CdS, MoS) can be synthesized, with many of them being produced by Fusarium sp. Notably, fungal spores from Fusarium oxysporum have the capability to synthesize ternary nanocomposites, including BaTiO3 and Bi2O3 [55,56].

3.1.3. Biosynthesis mediated by microalgaeMicroalgae contain various active metabolites that serve as reducing and capping agents for MNPs, including polysaccharides, pigments, alkaloids, quinones, and terpenoids [57,58]. Chaudhary's review indicates that 49 species of green algae, 38 species of brown algae, 23 species of red algae, and 21 species of blue-green algae are capable of generating various MNPs [59]. Furthermore, Chlorella vulgaris has been suspected of synthesizing several rare MNPs such as Ir, Ru, and Rh NPs, which are typically challenging to biosynthesize [60]. It has also been reported that microalgae can produce a more diverse array of the shapes of MNPs compared to fungi and bacteria [44]. Consequently, microalgae appear to be promising hosts for the synthesis of MNPs.

3.1.4. Biosynthesis mediated by virusesViruses are used as biological templates for the synthesis of MNPs due to their unique size and structure. Notable examples include, Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), M13 virus, fd virus, cowpea mosaic virus (CPMV) and T4 virus [61]. In many cases, additional reducing agents (such as DMAB, NH2OH, NaBH4, or UV irradiation) are required to reduce the metal precursor. Nevertheless, the reduction of metal ions with high positive reduction potentials, including Au3+, Ag+ and Pt2+, can be achieved through the exposed amino acid residues (cysteine, tyrosine, lysine) on the protective capsid protein structure of viruses.

3.1.5. Biosynthesis mediated by microbial EPSsExtracellular polymeric substances (EPSs) are complex mixtures of high macromolecular polymers secreted by both prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. They consist of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, humic acids, and other biomolecules [62-64]. EPSs-mediated synthesis of MNPs is gaining recognition as a simple, convenient and environmentally friendly method. For instance, xanthan gum, a kind of heteropolysaccharide EPSs, has demonstrated the ability to produce spherical Ag, Au, and Pd NPs with excellent catalytic properties [65-67]. Additionally, purified carboxyl gel has been utilized as a stabilizer or reductant to synthesize homogeneous and monodisperse Se NPs as well as spherically agglomerated ZnO NPs [68,69]. Schizophyllan (SPN) isolated from the macro-fungus Schizophyllum commune, has played a crucial role in the synthesis of one-dimensional Au nanowires and Ag NPs/SPN nanocomposites [70,71]. EPSs from the terrestrial cyano-bacterium Nostoc commune and the micro-algae Scenedesmu sp. have demonstrated the ability to compose and stabilize Ag NPs [72,73]. In the case of complex microbial communities, EPSs extracted from freshwater biofilms have been shown to stabilize and modify CeO2 NPs and Ag NPs [74]. Sludge EPSs have been reported to increase the stability of CuO NPs [75], while EPSs from anaerobic granular sludge form an organic layer on Se NPs, stabilizing them in colloidal suspension [76]. Although microbial synthesis is considered a green and attractive method for synthesizing MNPs, effectively controlling the shape, size, and composition of MNPs remains a significant and urgent challenge in the industrial production of bio-MNPs.

3.1.6. Biosynthesis mediated by natural microbiomesAdditionally, a few natural microbiomes have been reported to contain the capability to synthesize MNPs. Lichens, a kind of natural microbiome composed of several fungal and algal symbioses, have been reported to mediate the synthesis of various MNPs, including Au NPs, Ag NPs, metal oxides (e.g., iron oxide and zinc oxide NPs), bimetallic alloys (Au-Ag NPs), and nanocomposites (e.g., ZnO@TiO2@SiO2 and Fe3O4@SiO2 NPs) [77]. High moisture content containing in surface of human body results in the prevalence of microorganisms as commensals. Cultivable microbiota collected from healthy human skin have been shown to synthesize spherical Au NPs [78]. Similarly, human intestinal microbiota cultured in vitro can biosynthesize near-spherical bio-Ag NPs ranging with a size of 34±10 nm on the cytoplasmic membrane or within the cytoplasm [79]. The symbiotic members of the microbial community can also reduce the toxicity of metal ions through quorum sensing and metabolic interactions [80]. In theory, symbiotic members of the microbiome can perform complex functions that cannot be achieved by a single strain, through information exchange and metabolic interaction. But there have been no studies on the construction of microbiomes specifically designed for the production of MNPs, according to the literature investigation.

3.2. Mechanism of synthesis of MNPs by microorganismsMicrobial reduction of metal ions usually occurs as a detoxification mechanism, which can be achieved through intracellular and/or extracellular pathways [81,82]. Various enzymes (such as nitrate reductase, catalase, cytochrome reductase) and metabolites (including amino acids, polysaccharides, sulfur-containing proteins) secreted by microorganisms play important roles in the synthesis and stable dispersion of MNPs [83,84]. These biomolecules possess various functional groups (such as –NH2, –OH, –COOH, –CHO, and –SH) with high affinity and reduction potential for metal ions [61]. Fig. 3 shows a schematic representation of the mechanism behind microbial synthesis of MNPs. Ion capping, transport, bioconjugation, and enzymatic catalysis are all integral processes in the reduction of metal ions by various microorganisms, with variations in specific enzymes or transporters among them [12,85]. Within a single microorganism, both intracellular and extracellular synthesis of MNPs can occur, and the relative rates determined by environmental conditions [12,86,87].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Possible mechanism of microbial intracellular or extracellular synthesis of MNPs. | |

Intracellular synthesis of MNPs depends on ion transport facilitated by enzymes and channel proteins [12,13]. Electrostatic interactions between metal ions and bacteria with electronegative surfaces serve as the driving force for the extracellular-to-intracellular ion transport [88]. Once inside the cells, metal ions undergo reduction through the action of reducing substances, often represented by oxidoreductases, resulting in the formation of MNPs within the cytoplasm [12,89-91]. Eventually, the MNPs formed intracellularly may detach from the cell [92].

Extracellular reduction of metal ions can occur either on the outer surface of the cell wall or within the culture medium [93]. This process is mediated by secretory reductases or reducing components present in the cell wall [92,94]. Electronegative functional groups on the cell wall attract metal ions, which will then nucleate and be reduced, resulting in the biosynthesis of MNPs [95]. Extracellularly secreted enzymes [96], polysaccharides [97], quinones [98], proteins [88], and phytochemicals [99], all contribute to the biosynthesis of MNPs. NADH-dependent nitrate reductase is a typical reductant for the conversion of metal ions into MNPs, particularly affecting the reduction of Ag+ and Au3+ [100-102].

As a unique metabolism-independent reduction, EPSs-mediated synthesis of MNPs can be performed in the absence of an electron donor [12]. Abundant reactive functional groups and non-carbohydrate substituents are contained in the EPSs, such as hydroxyl, sulfate, acetyl clusters in polysaccharides, amine, thiol, carboxyl groups in proteins and phosphate groups in nucleic acids, endow an overall negative charge [103,104]. Among the numerous polyanionic functional groups, hydroxyl, carboxyl, amino, and hemiacetal groups have been proposed as mediators in the reduction of metal ions to form corresponding MNPs [105]. The oxidation of hydroxyl groups to carbonyl, as well as the conversion of alcohol and aldehyde to carboxyl groups, are important factors in the reduction process [106]. Moreover, EPSs protect the primary structure of MNPs, prevent agglomeration, and improve compatibility between phases in the system, acting as a natural encapsulating film and effective stabilizer [107,108].

3.3. Structure and characterization of bio-MNPsA wide range of MNPs synthesized by various microorganisms have been extensively explored. Well-studied bio-MNPs include various monometallic nanoparticles (e.g., Cu, Fe, Al) and noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Au, Pt) [109]. The biosynthesis of magnetic nanoparticles, specifically Fe2O3 and Fe3O4 was among the earliest and most extensively studied metal oxide nanoparticles [110]. Successively, TiO2, Ag2O, CuO, ZnO, MnO2, CeO2 and Bi2O3 NPs were also found to be biosynthesized [43]. PbS, ZnS, CdS, MnS, NiS and HgS NPs can be biosynthesized through enzymatic catalysis or mediation of cysteines and peptides under lower redox potential conditions [109]. Moreover, metal salt nanoparticles such as PbCO3, CdCO3 and Zn3(PO4)2 NPs, can be fabricated during CO2 production by microorganisms or in the presence of phosphate [23,24]. Fig. 4 summarizes the biosynthesized metal and metalloid nanoparticles reported to date in the form of a periodic table of elements. It demonstrates that the diversity of bio-MNPs remains to be expanded, despite the wide range of metal or metalloid elements involved.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Spiral periodic table of elements showing the metal and metalloid nanoparticles that have been synthesized by microorganisms. | |

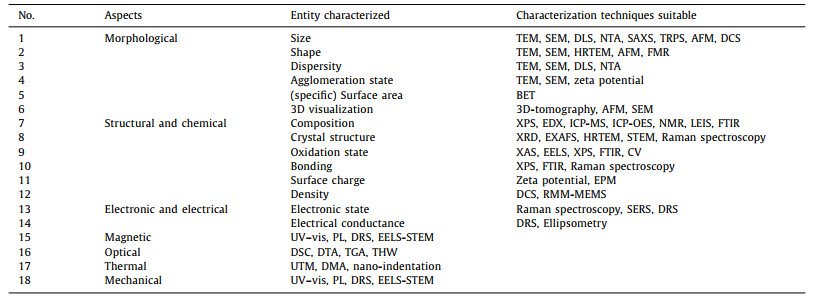

In addition to composition and type, MNPs can be distinguished by particle size, shape, and structure as well. MNPs can take on various shapes, including spheres, rods, cubes, triangles, and hexagons. Sequential reduction for at least two metal ions can result in MNPs with a core-shell structure, whereas alloyed NPs are formed [111]. Furthermore, properties such as surface area, homogeneity, stability, chemical composition, and crystal structure can provide valuable insights into the potential functions of MNPs [112,113]. Therefore, it is essential to characterize MNPs using a variety of advanced techniques. Table 1 provides an overview of targeted characterization techniques for different aspects of MNPs. In practice, these techniques are typically complimentary, with factors such as availability, cost, accuracy, and non-destructiveness often influencing the choice of method.

|

|

Table 1 Techniques for the characterization of MNPs. |

To overcome the production limitations of MNPs by wild-type microorganisms, synthetic biology represented by genetic engineering is introduced [114]. The process of designing and constructing engineered microorganisms includes [115]: (1) Recognizing functional genes/enzymes involved in the synthetic pathways; (2) importing target genes into appropriate chassis strains to construct biosynthetic pathways; (3) identifying bottleneck pathways that limit production and enhancing the tolerance of chassis strains to various environmental stresses. Currently, the focus of genetically engineered microorganisms is primarily on simple biological systems like bacteria and yeast.

4.1. Biosynthesis by engineered bacteriaBacterial cells contain a lower number of relevant enzymes, non-enzymatic proteins, and peptides, resulting in a slower bio-reduction process compared to other complex microorganisms, such as fungi [116]. Therefore, it is a trendy strategy that using genetically engineered microorganisms to enhance the efficiency of metal ion reduction, achieve controllable synthesis of homogeneous MNPs, and expand the possibilities in bio-MNPs production. E. coli, which contains a strong synthetic capacity for a variety of substances, has gained widespread use as a chassis cell in genetic engineering modifications.

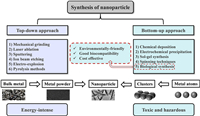

The introduction of exogenous genes and cell reprogramming to amplify the encoding genes of homologous or heterologous proteins responsible for reduction is the central approach in constructing synthesis-oriented genetically engineered bacteria. Previous researches have reported the co-expression of metallothionein (MT) and phytochelatin synthase (PCS) in engineered E. coli by introducing recombinant plasmids. MT is a metal-binding protein known for its ability to bind metals such as Cu, Cd, and Zn through thiol clusters [117]. Phytochelatin (PC) is a series of thiol-reactive peptides containing gamma-glutamate-cysteine repeating units, synthesized by PCS [118]. Both MT and PC are rich in cysteine, and the thiol groups in cysteine act as efficient reducing agents for metal ions. Recombinant E. coli co-expressing MT and PCS have been used to synthesize more than 60 different nanomaterials, including various combinations of semiconductors (Cd, Se, Zn, and Te), alkaline earth metals (Cs and Sr), magnetic metals (Fe, Co, Ni, and Mn), noble metals (Au and Ag) and lanthanide metals (Pr and Gd), some of that have never been synthesized by chemical methods [25,27]. Similarly, genes encoding other reductases, such as glutathione synthase or cysteine synthase, have been employed in the construction of genetically engineered bacteria [119,120]. These genetic manipulations have successfully enhanced the synthesis and accumulation of bio-MNPs, breaking through the limitations of biosynthesis to a certain extent [121-123]. With the increasing sophistication of genetic engineering methods, the manipulation of individual genes alone is no longer sufficient for the biosynthesis of high-quality MNPs. The limited control over the properties or self-assembly of MNPs has been achieved through the construction of genetic control circuits [124,125]. For example, an inducible system has been constructed to synthesize rounded iron oxide nanoparticles (IONPs) typically below 30 nm in size, with over 24 IONPs located on each intracellular chain [126]. This is a major breakthrough in the controllable synthesis of MNPs. Representative engineering bacteria and their manipulations during the development are summarized in Table 2.

|

|

Table 2 Representative engineering bacteria for the synthesis of MNPs. |

Yeasts are rich in reducing biomolecules, such as glutathione, metallothioneins and phytochelatins, which have been reported to provide a better control over particle size distribution compared to bacteria [28]. Several genetic engineering operations have been conducted using yeast as a chassis cell for fungal synthesis of MNPs. For example, transgenic Pichia pastoris strains overexpressing the cytochrome b5 reductase enzyme (Cyb5R), have been constructed to facilitate high-throughput accumulation, transformation, and intracellular production of stable and highly dispersed Ag NPs and Se NPs [127]. The recombinant P. pastoris strains are also capable of synthesizing Au NPs and Pd NPs, each around 100 nm in size, even at toxic concentrations of Au3+ and Pd2+ (10 mmol/L and 60 mmol/L, respectively) [128]. Furthermore, through insertion of the inducible promoter PGAL1 into the upstream region of the rate-limiting gene GSH1, PGAL1-GSH1 engineered yeast demonstrated a remarkable 5-fold increase in CdSe QD yields under galactose induction compared to the wild type [129]. It is important to note that there are significant gaps in the availability of genetic tools for synthesizing MNPs in fungi and yeasts compared to bacteria.

4.3. Biosynthesis by modified virusesThe ability of viruses to synthesize MNPs is often determined by the number of amino acid residues on the capsid protein [130]. Therefore, it is possible to enhance MNPs synthesis by specifically modifying the capsid protein. For instance, introducing cysteine and lysine residues to increase thiol groups has been shown to be effective [131]. A7 and Z8 peptides were expressed in the form of a pVIII fusion protein into the crystal capsid of the virus, resulting in the synthesis of well-crystallized ZnS NPs and CdS NPs [132]. The slow formation of large Au nanosheets was found to be promoted by GASL and SEKL as biocatalysts [133]. A pair of tryptophan (SEKLWWGASL) was further combined to increase the synthesis speed of Au NPs by more than five times and decrease the size of NPs from over 500 nm to about 40 nm [134]. The successful biosynthesis of 10–40 nm Au NPs was achieved by introducing SEKLWWGASL sequence into the surface-exposed loop of TMV capsid protein [135]. Additionally, TMV1cys and TMV2cys were constructed by inserting one or two cysteine residues into the amino terminus of TMV capsid protein, which could effectively improve the biological adsorption of metal ions and the biological synthesis of Ag, Au, Pd, and Pd-Au NPs [136,137]. However, virus-mediated MNPs synthesis still faces challenges such as limited genetic manipulation, safety and biocompatibility.

4.4. Biosynthesis by modified microbial EPSs or programmable biomoleculesAs far as we know, there have not been any unexpected advances in the synthesis of MNPs using genetically modified EPSs, although it remains a possibility. For example, EPSs secreted by Arthrospira platensis can increase under gamma irradiation stress, resulting in improved biosynthesis, dispersion and capping properties of Ag NPs [138]. An engineered strain F2-exoY-O, was constructed to produce EPSs containing significantly higher levels of polysaccharides than the wild type, resulting in higher Cr(VI) recovery rates due to the increased presence of polysaccharides (mainly hemiacetal groups) [139]. Similarly, mutants of Pseudomonas fluorescens with increased EPSs yield were screened through treatment with atmospheric and room temperature plasma (ARTP). These mutants exhibited higher flocculation activity, which facilitated the effective uptake of Cr(VI) [140]. The regulatory mechanisms of EPSs biosynthesis based on quorum sensing and c-di-GMP secondary messenger (activating pelD and alg44), as well as regulatory gene clusters of EPSs in various bacteria, have been summarized [141]. Additionally, a recent study introduced an AI-driven multivariate optimization strategy that combined h-SVM with RSM, to increase the EPSs production of Bacillus licheniformis by approximately 5-fold through optimizing the culture medium [142]. Although the genetically engineered bacteria mentioned above were not specifically constructed for MNPs synthesis, they provide possible directions for future design.

Moreover, it is worth mentioning that other programmable biomolecules, such as DNA, short peptides, and proteins, have demonstrated exceptional capabilities in the controllable synthesis of MNPs. The size, distribution, and elemental composition of Au-TiO2 nanocomposites can be precisely controlled by adjusting factors such as DNA length, peptide nucleic acid (PNA) number, and acridine binding sites on DNA for specific mineralization [143]. By changing the hydrophobicity, the number of carboxylates and amino groups, and the side-chain position of the peptoid, it becomes possible to transform the shape of Au NPs from spherical to coralloid [144]. It illustrates that a certain degree of predictability and controllability of MNPs can be achieved through the design of DNA or sequence-defined peptides.

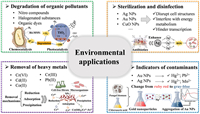

5. Environmental applications of bio–nanomaterialsDue to the advantages of green synthesis, metallicity and nanoscale, bio-MNPs have been widely used in the field of environmental remediation and heavy metal detection (Table S2 in Supporting information). Representative environmental applications of bio-MNPs and their remediation mechanisms are shown in Fig. 5, which are concentrated in the field of water treatment.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Representative environmental applications of bio-MNPs. | |

Current researches highlight the removal of nitro compounds, organic dyes and halogenated substances using bio-MNPs. Au NPs are widely used in the removal of nitro compounds. For instance, bio-Au NPs have been reported to exhibit powerful catalytic reduction properties towards nitroanilines and nitrophenols [145,146]. Bimetallic Pd-Pt NPs generated by S. oneidensis MR-1 using anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) as a mediator are more effective in the catalytic reduction of nitrophenols compared to Pd NPs or Pt NPs [147]. Organic dyes pose environmental risks due to their persistence and eutrophication potential. Biogenic Ag, Au, Pd, and Mo NPs have found extensive use in catalyzing the effective decolorization of organic azo dyes, such as methyl orange (MO) and methylene blue (MB) [1]. Metal oxides and metal sulfides are extensively applied in the photodegradation of organic pollutants, thanks to their suitable band gaps that can absorb photoenergy and excite electrons [148,149]. For example, SnO2 NPs synthesized by Erwinia herbicola achieved photocatalytic degradation rates of 93.3%, 94.0%, and 97.8% for MB, MO, and Erichrome black T (EBT), respectively [150]. ZnO NPs and TiO2 NPs also serve as excellent photocatalysts for the degradation of MB and MO [151,152]. Similarly, biosynthetic ZnS, CdS, and PbS NPs exhibit photodegradation activities towards rhodamine B (RhB), diphenyl blue and MB, respectively [153].

It has been widely reported that bio-Pd NPs exhibit excellent catalytic reduction, dehalogenation, and hydrogenation properties. During the dehalogenation of 2,3,4,5-tetrachlorobiphenyl, the release of chloride catalyzed by chemical Pd NPs is only 5% of that by bio-Pd NPs [154]. Efficient pilot-scale dechlorination of trichloroethylene (TCE) was achieved using bio-Pd NPs in combination with a membrane reactor or fixed-bed reactor [155,156]. Recently, D. vulgaris strains were used as the adsorption carriers to synthesize stably dispersed Pd NPs ranging from 3 nm to 6 nm. These nanoparticles could catalyze both dechlorination and defluorination reactions and were able to remove over 70% of CFC-11 within 15 h [157]. Magnetic nanoparticles such as Fe3O4 NPs have been used for the adsorption of F- ions from drinking water [158]. Consequently, there is potential to achieve complete removal of fluorinated compounds by combining different biogenic MNPs.

5.2. Removal of heavy metalsThere have also been excellent performances of bio-MNPs in the field of heavy metal removal. Pd NPs synthesized by Geobacter sulfurreducens strains can reduce carcinogenic Cr(VI) to the less toxic Cr(Ⅲ) [159]. Hollow rod-shaped bio-CuS NPs were capable of removing 95% of Cr(VI) in just 40 min, with a maximum adsorption capacity reaching up to 28.5 mg/g [153]. Furthermore, biogenic ZnO NPs showed excellent adsorption capacity for Cd2+, Co2+, and Pb2+, with maximum adsorption efficiencies of 85.63%, 71.23%, and 95.35% at different pH levels [160]. In addition to ion adsorption and reduction, iron oxide NPs synthesized by Aspergillus niger removed chromium ions from aqueous solutions by forming Fe(Ⅲ)-Cr(Ⅲ) complexes and precipitates, such as Cr(OH)2 and Cr2O3 [161]. It is obvious that bio-MNPs have great potential for the removal of heavy metal ions, and further design of nanomaterials to achieve higher removal efficiency is a promising perspective.

5.3. Sterilization and disinfectionNanoparticles exhibit a certain degree of toxicity to microorganisms due to their size effect. Ag, Au, CuO and ZnO NPs are the most prominent among the reported bio-MNPs with antibacterial properties. The release of Ag+ from Ag NPs leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), disrupting cell structures, genetic substances, and interfering with energy metabolism to achieve sterilization [162]. Extracellular Ag NPs synthesized by S. oneidensis MR-1 exhibit stronger antibacterial activity against Bacillus subtilis compared to chemically synthesized colloidal silver [163]. Au NPs exert bactericidal effects primarily through two mechanisms inhibiting ATPase activity and hindering transcription [164]. Bio-Au NPs have been reported to possess significant antibacterial activity by disrupting the cell membrane, comparable to standard antibacterial and antifungal drugs [165]. Significant antibacterial activity of bio-ZnO NPs was reported against pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Aspergillus flavus, and Enterococcus faecalis [166]. Bio-CuO NPs were capable of completely removing pathogens from infected drinking water (16,000 colonies/100 mL) within 30 min at a concentration of 40 mg/mL [167]. Furthermore, biosynthetic MgO NPs and TiO2 NPs possess certain antibacterial activity due to the production of ROS [49].

Bio-MNPs can enhance the effectiveness of conventional antibiotics in addition to their intrinsic antibacterial activity. For example, when combined with levofloxacin, Ag NPs prove effective against a variety of pathogens, including E. faecalis, E. coli, Salmonella typhi and Vibrio cholerae [168]. Similarly, when bio-Ag NPs are used in conjunction with oleandomycin, rifampicin, or penicillin G, the antibacterial efficacy against pathogenic strains is enhanced for all antibiotics [169].

5.4. Indicators of contaminantsMercury is a highly hazardous heavy metal element to the environment. When Au NPs synthesized by Trichoderma harzianum come into contact with Hg2+ in a solution, the color of the reaction system changes from ruby red to gray-blue [170]. This discoloration occurs because Hg2+ has a higher affinity for –SH than the Au–S bonds formed between Au NPs and cysteine. Therefore, a method was investigated for rapid detection of Hg2+ with a minimum detection limit of 2.6 nmol/L using the colorimetric response. Similarly, Ag NPs are highly sensitive to Hg2+ and Mn2+, just same as Au NPs are to Pb2+. These Ag NPs and Au NPs are stabilized by l-tyrosine under light, and they exhibit colorimetric detection limits as low as 16 nmol/L [171]. These convenient colorimetric methods can be used for the preliminary detection of some heavy metal ions, expanding the environmental applications of MNPs.

6. Machine learning guidance for metal nanomaterialsAs a branch of artificial intelligence, machine learning (ML) uses algorithms to infer mathematical models for performing certain tasks from a mass of data. Till date, numerous structure descriptors, including molecular structures, mechanical properties, and reaction conditions, have been developed for ML to analyze structural defects and assist in the design of desired chemical nanomaterials [172,173]. A computational method based on Monte Carlo tree search and recurrent neural networks has made significant contributions to the design of promising new metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [174]. A platform for autonomously driven synthesis of nanoparticles based on ML algorithms was constructed by Chen et al., to achieve a hierarchical evolution from spherical Au NPs to nanorods and then to octahedral nanoparticles by continuously optimizing and exploring the conditions required to synthesize various shapes of Au NPs [175].When coupled with data mining techniques, ML can also enable rapid screening of novel application-specific NMs from structural databases [176]. In conclusion, ML tools are useful for designing the structure of nanomaterials to enhance their adsorption or catalytic properties [30]. Furthermore, a bio-MNPs synthesis model based on classical nucleation theory has been achieved, providing mechanistic insights into how cells direct reactions for the formation of nanomaterials [177]. It indicates that the combined use of ML and omics technology is likely to be the future approach for intelligent and controllable synthesis processes.

The potential risks and toxicity of bio-MNPs to organisms and the environment should be carefully considered prior to their engineering applications. ML algorithms like SVM, decision tree, and regression algorithms are widely used to study the toxicity of metal oxide-based nanomaterials [178]. Deep neural networks (DNN) have been utilized in a few studies to enhance the predictive quality of other ML models for nanotoxicity [179]. Moreover, a synthetic gene circuit comprising four heat shock promoter (HSP) regions and a gene sequence encoding reporter proteins, was constructed to serve as a biosensor for nanomaterial-induced toxicity [180]. There are still significant gaps in detecting toxicity for complex bio-MNPs. Combining genetic circuits and ML methods for an accurate toxicological analysis presents a highly promising research approach.

7. Limitations and challengesCurrently, the biological synthesis of MNPs is primarily conducted at the laboratory scale. Wild-type microbe-mediated synthesis of MNPs remains limited by factors such as biosynthesis cycle, yield and structure of nanoparticles. While some recombinant microorganisms have been constructed to increase yield and control the size, shape, and chemical component of the MNPs to some extent, the types of chassis cells or molecules are intended to be expanded. Moreover, there is still significant room for improvement in the controllability of composition, structure, and synthesis process of bio-MNPs, especially for polymetallic nanomaterials.

Despite the remarkable green and low consumption advantages of biosynthesis, the admixture of biomolecules tends to affect some properties of MNPs, resulting in properties that are generally lower than those produced by chemical synthesis. Another challenge arises from the toxicological effects of MNPs in the environment [181]. The transportation of nanoparticles into cells can lead to oxidative stress and cellular toxicity [182]. Currently, toxicological analyses still rely primarily on long-term and costly biological experiments, with virtual toxicological predictions serving only as a secondary reference.

8. Conclusions and future prospectsBio-MNPs play an important role in environmental remediation, with providing a means to utilize hard-to-recycle metal ions at the nano-resource level. The synthesis of MNPs by physicochemical methods tends to be toxic and energy-intensive compared to biological methods. However, the limited synthesis capability and product structure of a single wild-type microorganism inhibit the scale-up of bio-MNPs to some extent. Currently, there is a considerable interest in developing more efficient methods for the synthesis of bio-MNPs. Several recombinant microorganisms have been constructed through techniques such as overexpression, co-expression, and gene circuit engineering, leading to breakthroughs in both yield and controllability of MNPs synthesis. Microalgae are able to grow and reproduce rapidly in nutrient-poor environments and synthesize MNPs of abundant types and shapes. It is of great value to utilize them as chassis cells in the future to construct modified microalgae for the synthesis of nanomaterials, taking advantage of their unique properties. Meanwhile, high-dimensional synthetic biology methods, such as synthetic microbiomes, have not been explored. Members of them may achieve complex functions that cannot be performed by a single strain by exchanging information and metabolic interactions. Constructing synthetic microbiomes is expected to improve production efficiency by decreasing the metabolic burden of a single strain. Machine learning is of great significance in guiding the design of targeted metal nanomaterials and predicting their toxicological effects. A pathway for combining in vivo cellular action with the guidance of computer has been established. Further controllable synthesis of bio-MNPs may depend on the combination of more complex genetic control circuits with ML tools. Moreover, there is a need for the development of rapid, simple, and cost-effective methods based on characterization data and ML modeling for toxicological analysis of bio-MNPs. In the foreseeable future, AI-driven machine learning is poised to lead the way in achieving more "intelligent" synthesis and toxicity prediction of bio-MNPs.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2020YFC1808204–01), Nanchang "Double Hundred Plan" Project (Innovative Talents - Talent Introduction), the State Key Laboratory of Urban Water Resource and Environment (Harbin Institute of Technology) (No. 2021TS11), Heilongjiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Environmental Biotechnology and Heilongjiang Touyan Innovation Team Program.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2024.109651.

| [1] |

A. Saravanan, P.S. Kumar, S. Karishma, et al., Chemosphere 264 (2021) 128580. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128580 |

| [2] |

P.C. Lin, S. Lin, P.C. Wang, R. Sridhar, Biotechnol. Adv. 32 (2014) 711-726. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.11.006 |

| [3] |

S. Das, J. Chakraborty, S. Chatterjee, H. Kumar, Environ. Sci.: Nano 5 (2018) 2784-2808. DOI:10.1039/C8EN00799C |

| [4] |

S. Linic, U. Aslam, C. Boerigter, M. Morabito, Nat. Mater. 14 (2015) 567-576. DOI:10.1038/nmat4281 |

| [5] |

A.B. Devi, D.S. Moirangthem, N.C. Talukdar, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 25 (2014) 1615-1619. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2014.07.014 |

| [6] |

B. Ajitha, Y.A.K. Reddy, P.S. Reddy, et al., J. Mol. Liq. 219 (2016) 474-481. DOI:10.1016/j.molliq.2016.03.041 |

| [7] |

R.A. de Jesus, G.C. de Assis, R.J. de Oliveira, et al., Environ. Technol. Innov. 24 (2021) 101851. DOI:10.1016/j.eti.2021.101851 |

| [8] |

G. Sathiyanarayanan, K. Dineshkumar, Y.H. Yang, Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 43 (2017) 731-752. DOI:10.1080/1040841X.2017.1306689 |

| [9] |

A. Schrofel, G. Kratosova, I. Safarik, et al., Acta Biomater. 10 (2014) 4023-4042. DOI:10.1016/j.actbio.2014.05.022 |

| [10] |

E.R. Bandala, D. Stanisic, L. Tasic, Environ. Sci.: Water Res. Technol. 6 (2020) 3195-3213. DOI:10.1039/D0EW00705F |

| [11] |

T.J. Park, K.G. Lee, S.Y. Lee, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100 (2016) 521-534. DOI:10.1007/s00253-015-6904-7 |

| [12] |

Y. Yang, G.I.N. Waterhouse, Y.L. Chen, D. Sun-Waterhouse, D.P. Li, Biotechnol. Adv. 55 (2022) 107914. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.107914 |

| [13] |

G. Kratosova, V. Holisova, Z. Konvickova, et al., Biotechnol. Adv. 37 (2019) 154-176. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.11.012 |

| [14] |

M. Aslam, A.Z. Abdullah, M. Rafatullah, J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 98 (2021) 1-16. DOI:10.1016/j.jiec.2021.04.010 |

| [15] |

A.K. Suresh, D.A. Pelletier, W. Wang, et al., Acta Biomater. 7 (2011) 2148-2152. DOI:10.1016/j.actbio.2011.01.023 |

| [16] |

M.M. Juibari, S. Abbasalizadeh, G.S. Jouzani, M. Noruzi, Mater. Lett. 65 (2011) 1014-1017. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2010.12.056 |

| [17] |

A. Syed, A. Ahmad, Colloids Surf. B 97 (2012) 27-31. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.03.026 |

| [18] |

S. Ahmed, An nu, S.A. Chaudhry, S. Ikram, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 166 (2017) 272-284. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2016.12.011 |

| [19] |

P. Dhandapani, S. Maruthamuthu, G. Rajagopal, J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 110 (2012) 43-49. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2012.03.003 |

| [20] |

S. Seshadri, K. Saranya, M. Kowshik, Biotechnol. Prog. 27 (2011) 1464-1469. DOI:10.1002/btpr.651 |

| [21] |

J. Liu, Y. Zheng, Z. Hong, et al., Sci. Adv. 2 (2016) 1600858. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1600858 |

| [22] |

H. Xu, Y. Xiao, M. Xu, et al., Nanotechnology 30 (2019) 065607. DOI:10.1088/1361-6528/aaf2a6 |

| [23] |

A. Sanyal, D. Rautaray, V. Bansal, A. Ahmad, M. Sastry, Langmuir 21 (2005) 7220-7224. DOI:10.1021/la047132g |

| [24] |

S. Yan, W. He, C. Sun, et al., Dyes Pigm. 80 (2009) 254-258. DOI:10.1016/j.dyepig.2008.06.010 |

| [25] |

Y. Choi, T.J. Park, D.C. Lee, S.Y. Lee, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 115 (2018) 5944-5949. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1804543115 |

| [26] |

J.H. Jung, S.Y. Lee, T.S. Seo, Small 14 (2018) 1803133. DOI:10.1002/smll.201803133 |

| [27] |

T.J. Park, S.Y. Lee, N.S. Heo, T.S. Seo, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49 (2010) 7019-7024. DOI:10.1002/anie.201001524 |

| [28] |

X. Zhang, S. Yan, R.D. Tyagi, R.Y. Surampalli, Chemosphere 82 (2011) 489-494. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.10.023 |

| [29] |

F. Ahmad, A. Mahmood, T. Muhmood, Biomater. Sci. 9 (2021) 1598-1608. DOI:10.1039/D0BM01672A |

| [30] |

Y.Y. Jia, X. Hou, Z.W. Wang, X.G. Hu, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9 (2021) 6130-6147. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00483 |

| [31] |

B.C. Yadav, S. Singh, T.P. Yadav, Synth. React. Inorg. M. 45 (2015) 487-494. DOI:10.1080/15533174.2012.749892 |

| [32] |

E. Jimenez, K. Abderrafi, R. Abargues, J.L. Valdes, J.P. Martinez-Pastor, Langmuir 26 (2010) 7458-7463. DOI:10.1021/la904179x |

| [33] |

D. Zhang, K. Ye, Y. Yao, et al., Carbon 142 (2019) 278-284. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2018.10.062 |

| [34] |

J. Jeevanandam, A. Barhoum, Y.S. Chan, A. Dufresne, M.K. Danquah, Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 9 (2018) 1050-1074. DOI:10.3762/bjnano.9.98 |

| [35] |

E. Temeche, E. Yi, V. Keshishian, J. Kieffer, R.M. Laine, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 39 (2019) 1263-1270. DOI:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2018.11.051 |

| [36] |

S.A. Bello, J.O. Agunsoye, S.B. Hassan, Mater. Lett. 159 (2015) 514-519. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2015.07.063 |

| [37] |

J. Yang, T. Ling, W.T. Wu, et al., Nat. Commun. 4 (2013) 1695. DOI:10.1038/ncomms2637 |

| [38] |

A. Veksha, N.M. Latiff, W. Chen, J.E. Ng, G. Lisak, Carbon 167 (2020) 104-113. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.05.075 |

| [39] |

L. Cabrera, S. Gutierrez, N. Menendez, M.P. Morales, P. Herrasti, Electrochim. Acta 53 (2008) 3436-3441. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2007.12.006 |

| [40] |

M. Parashar, V.K. Shukla, R. Singh, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 31 (2020) 3729-3749. DOI:10.1007/s10854-020-02994-8 |

| [41] |

K.R. Aadil, S.I. Mussatto, H. Jha, Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 120 (2018) 763-767. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.08.109 |

| [42] |

S.S. Salem, A. Fouda, Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 199 (2021) 344-370. DOI:10.1007/s12011-020-02138-3 |

| [43] |

S.H. Gebre, M.G. Sendeku, SN Appl. Sci. 1 (2019) 928. DOI:10.1007/s42452-019-0931-4 |

| [44] |

M. Huston, M. DeBella, M. DiBella, A. Gupta, Nanomaterials 11 (2021) 2130. DOI:10.3390/nano11082130 |

| [45] |

M. Abdollahnia, A. Makhdoumi, M. Mashreghi, H. Eshghi, PLoS One 15 (2020) 0229886. |

| [46] |

T. Milojevic, M. Albu, A. Blazevic, et al., Front. Microbiol. 10 (2019) 01267. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01267 |

| [47] |

S. Kitjanukit, K. Sasaki, N. Okibe, Extremophiles 23 (2019) 549-556. DOI:10.1007/s00792-019-01106-7 |

| [48] |

S. Ahmad, S. Munir, N. Zeb, et al., Int. J. Nanomedicine 14 (2019) 5087-5107. DOI:10.2147/IJN.S200254 |

| [49] |

O. Mat'atkova, J. Michailidu, A. Miskovska, et al., Biotechnol. Adv. 58 (2022) 107905. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2022.107905 |

| [50] |

K.B. Narayanan, N. Sakthivel, J. Hazard. Mater. 189 (2011) 519-525. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.02.069 |

| [51] |

Q. Li, F. Liu, M. Li, C. Chen, G.M. Gadd, Fungal Biol. Rev. 41 (2022) 31-44. DOI:10.1016/j.fbr.2021.07.003 |

| [52] |

Z. Molnar, V. Bodai, G. Szakacs, et al., Sci. Rep. 8 (2018) 3943. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-22112-3 |

| [53] |

M.G. Casagrande, R. de Lima, Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7 (2019) 00287. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2019.00287 |

| [54] |

J.G. Fernandez, M.A. Fernandez-Baldo, E. Berni, et al., Process. Biochem. 51 (2016) 1306-1313. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2016.05.021 |

| [55] |

V. Bansal, P. Poddar, A. Ahmad, M. Sastry, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 11958-11963. DOI:10.1021/ja063011m |

| [56] |

I. Uddin, S. Adyanthaya, A. Syed, et al., J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 8 (2008) 3909-3913. DOI:10.1166/jnn.2008.179 |

| [57] |

R. Nitnavare, J. Bhattacharya, S. Thongmee, S. Ghosh, Sci. Total. Environ. 841 (2022) 156457. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156457 |

| [58] |

S.S. Chan, S.S. Low, K.W. Chew, et al., Environ. Res. 212 (2022) 113140. DOI:10.1016/j.envres.2022.113140 |

| [59] |

R. Chaudhary, K. Nawaz, A.K. Khan, et al., Biomolecules 10 (2020) 10111498. |

| [60] |

T. Luangpipat, I.R. Beattie, Y. Chisti, R.G. Haverkamp, J. Nano Res. 13 (2011) 6439-6445. DOI:10.1007/s11051-011-0397-9 |

| [61] |

J. Huang, L. Lin, D. Sun, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 44 (2015) 6330-6374. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00133A |

| [62] |

G.P. Sheng, M.L. Zhang, H.Q. Yu, Colloids Surf. B 62 (2008) 83-90. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2007.09.024 |

| [63] |

S. Naveed, C. Li, X. Lu, et al., Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (2019) 1769-1802. DOI:10.1080/10643389.2019.1583052 |

| [64] |

N.A. Paul, R. de Nys, Aquaculture 281 (2008) 49-55. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.05.024 |

| [65] |

W. Xu, W. Jin, L. Lin, et al., Carbohydr. Polym. 101 (2014) 961-967. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.10.032 |

| [66] |

D. Pooja, S. Panyaram, H. Kulhari, S.S. Rachamalla, R. Sistla, Carbohydr. Polym. 110 (2014) 1-9. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.03.041 |

| [67] |

A.S. Kumari, M. Venkatesham, D. Ayodhya, G. Veerabhadram, Appl. Nanosci. 5 (2015) 315-320. DOI:10.1007/s13204-014-0320-7 |

| [68] |

J.K. Yan, W.Y. Qiu, Y.Y. Wang, et al., Carbohydr. Polym. 179 (2018) 19-27. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.063 |

| [69] |

J.K. Yan, Y.Y. Wang, L. Zhu, J.Y. Wu, RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 77752-77759. DOI:10.1039/C6RA15395J |

| [70] |

A.H. Bae, M. Numata, S. Yamada, S. Shinkai, New J. Chem. 31 (2007) 618-622. DOI:10.1039/b615757b |

| [71] |

A.M. Abdel-Mohsen, R.M. Abdel-Rahman, M.M.G. Fouda, et al., Carbohydr. Polym. 102 (2014) 238-245. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.11.040 |

| [72] |

F.M. Morsy, N.A. Nafady, M.H. Abd-Alla, D.J.U.J.M.R. Elhady, Univ. J. Microbiol. Res. 2 (2014) 36-43. DOI:10.13189/ujmr.2014.020303 |

| [73] |

V. Patel, D. Berthold, P. Puranik, M. Gantar, Biotechnol. Rep. 5 (2015) 112-119. DOI:10.1016/j.btre.2014.12.001 |

| [74] |

A. Kroll, R. Behra, R. Kaegi, L. Sigg, PLoS One 9 (2014) 0110709. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0110709 |

| [75] |

L. Miao, C. Wang, J. Hou, et al., J. Nano Res. 17 (2015) 404. DOI:10.1007/s11051-015-3208-x |

| [76] |

R. Jain, N. Jordan, S. Weiss, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 49 (2015) 1713-1720. DOI:10.1021/es5043063 |

| [77] |

R.S. Hamida, M.A. Ali, N.E. Abdelmeguid, et al., J. Fungi 7 (2021) 291. DOI:10.3390/jof7040291 |

| [78] |

P. Deshpande, S. Gaidhani, M. Hitendra, et al., J. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. 6 (2015) 1000300. |

| [79] |

N. Yin, R. Gao, B. Knowles, et al., Sci. Total. Environ. 651 (2019) 1489-1494. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.09.312 |

| [80] |

P.M. D'Costa, R.S.S. Kunkolienkar, A.G. Naik, R.K. Naik, R. Roy, J. Basic. Microbiol. 59 (2019) 979-991. DOI:10.1002/jobm.201900244 |

| [81] |

K. Yin, Q.N. Wang, M. Lv, L.X. Chen, Chem. Eng. J. 360 (2019) 1553-1563. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.10.226 |

| [82] |

J. Jeevanandam, S.F. Kiew, S. Boakye-Ansah, et al., Nanoscale 14 (2022) 2534-2571. DOI:10.1039/D1NR08144F |

| [83] |

L. Karthik, G. Kumar, A.V. Kirthi, A.A. Rahuman, K.V.B. Rao, Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 37 (2014) 261-267. DOI:10.1007/s00449-013-0994-3 |

| [84] |

M. Sabaty, C. Avazeri, D. Pignol, A. Vermeglio, Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67 (2001) 5122-5126. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.11.5122-5126.2001 |

| [85] |

N. Duran, P.D. Marcato, M. Duran, et al., Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 90 (2011) 1609-1624. DOI:10.1007/s00253-011-3249-8 |

| [86] |

I. Barwal, P. Ranjan, S. Kateriya, S.C. Yadav, J. Nanobiotechnol. 9 (2011) 56. DOI:10.1186/1477-3155-9-56 |

| [87] |

J. Jena, N. Pradhan, R.R. Nayak, et al., J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24 (2014) 522-533. DOI:10.4014/jmb.1306.06014 |

| [88] |

K. Luo, S. Jung, K.H. Park, Y.R. Kim, J. Agric. Food Chem. 66 (2018) 957-962. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.7b05092 |

| [89] |

K. Sneha, M. Sathishkumar, J. Mao, I.S. Kwak, Y.S. Yun, Chem. Eng. J. 162 (2010) 989-996. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2010.07.006 |

| [90] |

P.S. Rajegaonkar, B.A. Deshpande, M.S. More, et al., Mater. Sci. Eng. C 93 (2018) 623-629. DOI:10.1016/j.msec.2018.08.025 |

| [91] |

Z. Zhang, G. Chen, Y. Tang, Chem. Eng. J. 351 (2018) 1095-1103. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.172 |

| [92] |

N.I. Hulkoti, T.C. Taranath, Colloids Surf. B 121 (2014) 474-483. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2014.05.027 |

| [93] |

J. Atalah, G. Espina, L. Blamey, S.A. Munoz-Ibacache, J.M. Blamey, Front. Microbiol. 13 (2022) 855077. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2022.855077 |

| [94] |

H.M. Yusof, R. Mohamad, U.H. Zaidan, N.A.A. Rahman, J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 10 (2019) 57. DOI:10.1186/s40104-019-0368-z |

| [95] |

E. Beeler, O.V. Singh, World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 32 (2016) 156. DOI:10.1007/s11274-016-2111-7 |

| [96] |

P. Velmurugan, M. Iydroose, M.H.A.K. Mohideen, et al., Bioprocess. Biosyst. Eng. 37 (2014) 1527-1534. DOI:10.1007/s00449-014-1124-6 |

| [97] |

F. Kang, X. Qu, P.J.J. Alvarez, D. Zhu, Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2017) 2776-2785. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.6b05930 |

| [98] |

M. Ovais, A.T. Khalil, M. Ayaz, et al., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19 (2018) 19124100. |

| [99] |

M. Govindappa, H. Farheen, C.P. Chandrappa, et al., Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. 7 (2016) 035014. DOI:10.1088/2043-6262/7/3/035014 |

| [100] |

N. Duran, P.D. Marcato, O.L. Alves, G.I.H.D. Souza, E. Esposito, J. Nanobiotechnol. 3 (2005) 8. DOI:10.1186/1477-3155-3-8 |

| [101] |

S.A. Kumar, M.K. Abyaneh, S.W. Gosavi, et al., Biotechnol. Lett. 29 (2007) 439-445. DOI:10.1007/s10529-006-9256-7 |

| [102] |

S.Y. He, Z.R. Guo, Y. Zhang, et al., Mater. Lett. 61 (2007) 3984-3987. DOI:10.1016/j.matlet.2007.01.018 |

| [103] |

Q. Saeed, W. Xiukang, F.U. Haider, et al., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021) 221910529. |

| [104] |

P. Gupta, B. Diwan, Biotechnol. Rep. 13 (2017) 58-71. DOI:10.1016/j.btre.2016.12.006 |

| [105] |

G. Gahlawat, A.R. Choudhury, RSC Adv. 9 (2019) 12944-12967. DOI:10.1039/C8RA10483B |

| [106] |

Y.N. Mata, E. Torres, M.L. Blazquez, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 166 (2009) 612-618. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.11.064 |

| [107] |

S. Noel, B. Leger, A. Ponchel, et al., Catal. Today 235 (2014) 20-32. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2014.03.030 |

| [108] |

S. Davidovic, V. Lazic, I. Vukoje, et al., Colloids Surf. B 160 (2017) 184-191. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.09.031 |

| [109] |

J. Yuan, J. Cao, F. Yu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. B 9 (2021) 6491-6506. DOI:10.1039/D1TB01000J |

| [110] |

I. Ali, C. Peng, Z.M. Khan, I. Naz, J. Basic Microbiol. 57 (2017) 643-652. DOI:10.1002/jobm.201700052 |

| [111] |

F. Wang, W. Zhang, H. Wan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2259-2269. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.074 |

| [112] |

N. Joudeh, D. Linke, J. Nanobiotechnol. 20 (2022) 262. DOI:10.1186/s12951-022-01477-8 |

| [113] |

S. Mourdikoudis, R.M. Pallares, N.T.K. Thanh, Nanoscale 10 (2018) 12871-12934. DOI:10.1039/C8NR02278J |

| [114] |

R. Dhanker, T. Hussain, P. Tyagi, K.J. Singh, S.S. Kamble, Front. Microbiol. 12 (2021) 638003. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2021.638003 |

| [115] |

W.L. Yan, Z.B. Cao, M.Z. Ding, Y.J. Yuan, Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 8 (2023) 176-185. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2022.11.001 |

| [116] |

Y. Choi, S.Y. Lee, Nat. Rev. Chem. 4 (2020) 638-656. DOI:10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w |

| [117] |

D.H. Hamer, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 55 (1986) 913-951. DOI:10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.004405 |

| [118] |

C.S. Cobbett, Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 3 (2000) 211-216. DOI:10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00066-2 |

| [119] |

S.H. Kang, K.N. Bozhilov, N.V. Myung, A. Mulchandani, W. Chen, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (2008) 5186-5189. DOI:10.1002/anie.200705806 |

| [120] |

Y.L. Chen, H.Y. Tuan, C.W. Tien, et al., Biotechnol. Prog. 25 (2009) 1260-1266. DOI:10.1002/btpr.199 |

| [121] |

I.W.S. Lin, C.N. Lok, C.M. Che, Chem. Sci. 5 (2014) 3144-3150. DOI:10.1039/C4SC00138A |

| [122] |

Q. Yuan, M. Bomma, Z. Xiao, Materials 12 (2019) 12244180. |

| [123] |

I. Kolinko, A. Lohsse, S. Borg, et al., Nat. Nanotechnol. 9 (2014) 193-197. DOI:10.1038/nnano.2014.13 |

| [124] |

T.T. Olmez, E.S. Kehribar, M.E. Isilak, T.K. Lu, U.O.S. Seker, ACS Synth. Biol. 8 (2019) 2152-2162. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00235 |

| [125] |

P. Chellamuthu, K. Naughton, S. Pirbadian, et al., Front. Microbiol. 10 (2019) 00938. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00938 |

| [126] |

M. Furubayashi, A.K. Wallace, L.M. Gonzalez, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (2021) 202004813. |

| [127] |

F. Elahian, S. Reiisi, A. Shahidi, S.A. Mirzaei, Nanomedicine 13 (2017) 853-861. DOI:10.1016/j.nano.2016.10.009 |

| [128] |

F. Elahian, R. Heidari, V.R. Charghan, E. Asadbeik, S.A. Mirzaei, Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 48 (2020) 259-265. DOI:10.1080/21691401.2019.1699832 |

| [129] |

Y. Li, R. Cui, P. Zhang, et al., ACS Nano 7 (2013) 2240-2248. DOI:10.1021/nn305346a |

| [130] |

O.O. Adigun, E.L. Retzlaff-Roberts, G. Novikova, et al., Langmuir 33 (2017) 1716-1724. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b03341 |

| [131] |

K.Z. Lee, V. Basnayake Pussepitiyalage, Y.H. Lee, et al., Biotechnol. J. 16 (2021) 2000311. DOI:10.1002/biot.202000311 |

| [132] |

C.B. Mao, C.E. Flynn, A. Hayhurst, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100 (2003) 6946-6951. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0832310100 |

| [133] |

S. Brown, M. Sarikaya, E. Johnson, J. Mol. Biol. 299 (2000) 725-735. DOI:10.1006/jmbi.2000.3682 |

| [134] |

Y.N. Tan, J.Y. Lee, D.I.C. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132 (2010) 5677-5686. DOI:10.1021/ja907454f |

| [135] |

A.J. Love, V.V. Makarov, O.V. Sinitsyna, et al., Front. Plant Sci. 6 (2015) 00984. |

| [136] |

S.Y. Lee, E. Royston, J.N. Culver, M.T. Harris, Nanotechnology 16 (2005) 435-441. DOI:10.1088/0957-4484/16/7/019 |

| [137] |

C. Yang, C.H. Choi, C.S. Lee, H. Yi, ACS Nano 7 (2013) 5032-5044. DOI:10.1021/nn4005582 |

| [138] |

R.A. Hamouda, M.H. Hussein, A.M.A. Elhadary, M.A. Abuelmagd, Appl. Nanosci. 10 (2020) 3839-3855. DOI:10.1007/s13204-020-01490-z |

| [139] |

S. Pi, A. Li, J. Qiu, et al., J. Clean. Prod. 279 (2021) 123829. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123829 |

| [140] |

L. Yang, Z. Chen, Y. Zhang, et al., Bioresour. Bioprocess. 10 (2023) 17. DOI:10.1186/s40643-023-00638-3 |

| [141] |

Vandana, S. Das, Carbohydr. Polym. 291 (2022) 119536. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119536 |

| [142] |

R. Rabiya, R. Sen, Biochem. Eng. J. 178 (2022) 108271. DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2021.108271 |

| [143] |

M. Ozaki, T. Imai, T. Tsuruoka, et al., Commun. Chem. 4 (2021) 1. DOI:10.1038/s42004-020-00440-8 |

| [144] |

F. Yan, L. Liu, T.R. Walsh, et al., Nat. Commun. 9 (2018) 2327. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-04789-2 |

| [145] |

C. Shi, N. Zhu, Y. Cao, P. Wu, Nanoscale Res. Lett. 10 (2015) 147. DOI:10.1186/s11671-015-0856-9 |

| [146] |

X. Zhang, Y. Qu, W. Shen, et al., Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 497 (2016) 280-285. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.02.033 |

| [147] |

Y. Tuo, G.F. Liu, B. Dong, et al., Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24 (2017) 5249-5258. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-8276-7 |

| [148] |

J. Li, Z.Z. Lou, B.J. Li, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1154-1168. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.07.059 |

| [149] |

K. Zhang, G. Lu, Z. Xi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 2207-2211. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.12.021 |

| [150] |

N. Srivastava, M. Mukhopadhyay, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 53 (2014) 13971-13979. DOI:10.1021/ie5020052 |

| [151] |

R.M. Tripathi, A.S. Bhadwal, R.K. Gupta, et al., J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biol. 141 (2014) 288-295. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.10.001 |

| [152] |

J. Fulekar, D.P. Dutta, B. Pathak, M.H. Fulekar, J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93 (2018) 736-743. DOI:10.1002/jctb.5423 |

| [153] |

M.R. Hosseini, M.N. Sarvi, Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 40 (2015) 293-301. DOI:10.1016/j.mssp.2015.06.003 |

| [154] |

V.S. Baxter-Plant, I.P. Mikheenko, M. Robson, S.J. Harrad, L.E. Macaskie, Biotechnol. Lett. 26 (2004) 1885-1890. DOI:10.1007/s10529-004-6039-x |

| [155] |

T. Hennebel, H. Simoen, W. De Windt, et al., Biotechnol. Bioeng. 102 (2009) 995-1002. DOI:10.1002/bit.22138 |

| [156] |

T. Hennebel, P. Verhagen, H. Simoen, et al., Chemosphere 76 (2009) 1221-1225. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.05.046 |

| [157] |

Y.H. Luo, M. Long, Y. Zhou, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 56 (2022) 13357-13367. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.2c03532 |

| [158] |

S. Kumari, S. Khan, Sci. Rep. 7 (2017) 8070. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-08594-7 |

| [159] |

M.P. Watts, V.S. Coker, S.A. Parry, et al., Appl. Catal. B 170 (2015) 162-172. |

| [160] |

P. Somu, S. Paul, J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 93 (2018) 2962-2976. DOI:10.1002/jctb.5655 |

| [161] |

S. Chatterjee, S. Mahanty, P. Das, P. Chaudhuri, S. Das, Chem. Eng. J. 385 (2020) 123790. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123790 |

| [162] |

T.C. Dakal, A. Kumar, R.S. Majumdar, V. Yadav, Front. Microbiol. 7 (2016) 1831. |

| [163] |

A.K. Suresh, D.A. Pelletier, W. Wang, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (2010) 5210-5215. DOI:10.1021/es903684r |

| [164] |

Y. Cui, Y. Zhao, Y. Tian, et al., Biomaterials 33 (2012) 2327-2333. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.11.057 |

| [165] |

M.M. Hulikere, C.G. Joshi, A. Danagoudar, et al., Process Biochem. 63 (2017) 137-144. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2017.09.008 |

| [166] |

C. Jayaseelan, A.A. Rahuman, A.V. Kirthi, et al., Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 90 (2012) 78-84. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2012.01.006 |

| [167] |

P. Bhattacharya, S. Swarnakar, S. Ghosh, S. Majumdar, S. Banerjee, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7 (2019) 102867. DOI:10.1016/j.jece.2018.102867 |

| [168] |

A. Keshari, R. Srivastava, S. Yadav, G. Nath, S. Gond, Nanomed. Res. J. 5 (2020) 44-54. |

| [169] |

P. Singh, Y.J. Kim, H. Singh, et al., Int. J. Nanomed. 10 (2015) 2567. |

| [170] |

R.M. Tripathi, R.K. Gupta, P. Singh, et al., Sens. Actuators B: Chem. 204 (2014) 637-646. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2014.08.015 |

| [171] |

M. Annadhasan, T. Muthukumarasamyvel, V.R.S. Babu, N. Rajendiran, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2 (2014) 887-896. DOI:10.1021/sc400500z |

| [172] |

X. Yan, A. Sedykh, W. Wang, B. Yan, H. Zhu, Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 2519. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-16413-3 |

| [173] |

D.P. Russo, X. Yan, S. Shende, et al., Anal. Chem. 92 (2020) 13971-13979. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.0c02878 |

| [174] |

X. Zhang, K. Zhang, Y. Lee, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12 (2020) 734-743. DOI:10.1021/acsami.9b17867 |

| [175] |

X. Chen, H. Lv, NPG Asia Mater. 14 (2022) 69. DOI:10.1038/s41427-022-00416-1 |

| [176] |

A.S. Barnard, G. Opletal, Nanoscale 11 (2019) 23165-23172. DOI:10.1039/C9NR03940F |

| [177] |

K.L. Naughton, J.Q. Boedicker, ACS Synth. Biol. 10 (2021) 3475-3488. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.1c00412 |

| [178] |

E.A. Bamidele, A.O. Ijaola, M. Bodunrin, et al., Adv. Eng. Inform. 52 (2022) 101593. DOI:10.1016/j.aei.2022.101593 |

| [179] |

H.J. Huang, Y.H. Lee, Y.H. Hsu, et al., Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22 (2021) 4216. DOI:10.3390/ijms22084216 |

| [180] |

B. Saltepe, E.U. Bozkurt, N. Haciosmanoglu, U.O.S. Seker, ACS Synth. Biol. 8 (2019) 2404-2417. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.9b00291 |

| [181] |

Y.P. Jia, B.Y. Ma, X.W. Wei, Z.Y. Qian, Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 691-702. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.01.021 |

| [182] |

X.L. Chang, L.Y. Chen, B.N. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3303-3314. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.057 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35