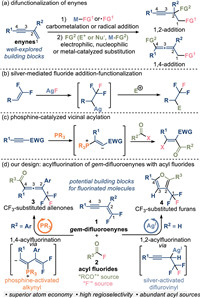

Enynes, as highly adaptable building blocks, manifest the capacity to engage in diverse transformations, resulting in regiodivergent difunctionalized products [1-9]. For instance, 1, 2-addition engenders disubstituted alkynes, while 1, 4-addition furnishes difunctionalized allenes (Fig. 1a). Given the pivotal role of molecules containing trifluoromethyl (CF3) moiety in chemistry [10-17], extensive research endeavors have been dedicated to devising methodologies that enable the introduction of trifluoromethyl groups into intricate molecules [18-27]. The gem-difluoroenynes (1) are a class of distinctive enyne derivatives that are easily obtainable but rarely investigated [28-32]. This kind of derivative possesses both a difluoroalkenyl and an electron-deficient alkynyl group. The addition of fluoride to the difluoroalkenyl component offers an efficient route to furnish CF3-substituted molecules (Fig. 1b) [33-37].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Acylfluorination of difluoroenynes: background. | |

Typically, the conversion of difluoroalkenyl into trifluoromethyl involves the addition of equivalent fluorination reagents such as silver fluoride. Subsequently, the resulting intermediates can engage in reactions with diverse electrophilic reagents, including protons, olefins or aryl iodides [38-43]. Acyl fluorides (2) are carboxylic acid derivatives with unique reactivity, which generally serve as acylating reagents [44-53]. The fluorine atom within acyl fluorides can also be harnessed, rendering them potential agents for fluorination [54]. Tertiary phosphines have the capacity to undergo addition into electron-deficient triple bond, resulting in the formation of a β-phosphonium α-carbanion species (Fig. 1c) [55]. The ensuing carbanion exhibits sufficient nucleophilicity to engage with an acylation reagent [54-57].

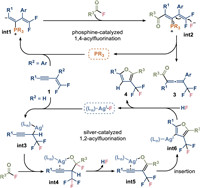

Herein we reported a protocol for the acylfluorination of difluoroenynes [58,59], offering access to a diverse array of CF3-substituted compounds, including allenones and furans (Fig. 1d). Our approach involves employing phosphine catalysis to effectuate the 1, 4-acylfluorination of difluoroenynes. The phosphine species activates the alkynyl moiety of the difluoroenyne, leading to the formation of a phosphonium intermediate. Under the circumstances, the subsequent acylation preferentially takes place at the alkynyl position, yielding CF3-substituted allenones (3) as the principal products. Alternatively, the difluoroalkenyl group can engage in addition with silver fluoride. In instances where the substituent group in 2-position in the difluoroenyne is hydrogen, facile transformation to an enolate complex is facilitated by silver-induced processes. The outcome of subsequent intramolecular cyclization is the formation of a CF3-substituted furan.

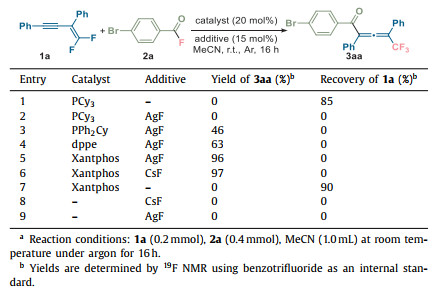

To validate our hypotheses, we initiated an investigation into the interaction between acyl fluoride (2a) and gem-difluoroenynes (1a), employing PCy3 (tricyclohexyl phosphine) as the catalyst.

However, no discernible acylfluorinated products were observed initially (Table 1, entry 1). Subsequent experimentation involving the utilization of phenyl-substituted phosphine in conjunction with additional silver fluoride led to successful promotion of the acylfluorination process, resulting in the identification of trifluoromethyl-substituted allenone (3aa) with a modest yield of 46% (entry 3). After a comprehensive assessment of various phosphine ligands (entries 2–5 in Table 1, for more details see Table S1 in Supporting information), we found that Xantphos (4, 5-bis(diphenylphosphino)-9, 9-dimethylx-anthene) was an effective catalyst that afforded the allenone product in 96% yield (entry 5). Notably, the additive silver fluoride could be substituted with cesium fluoride, yielding identical outcomes. Thus, silver was not necessary for this reaction. The phosphine could promote the allenone formation in the presence of the fluoride ion exclusively (entry 6). The control experiments (entries 7–9) resulted in no reaction when using solely the Xantphos catalyst or the metal fluoride additives. The relative equivalence of fluoride yielded negligible influence on the reaction outcome (Table S2 in Supporting information), implying that acyl fluorides serve both as acylating and fluorinating agents in a high atom-economic manner. It is noteworthy that no detection of 2-position-acylated products across all optimization experiments.

|

|

Table 1 Optimizations for acylfluorination.a |

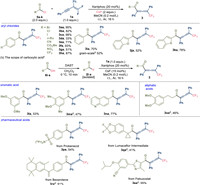

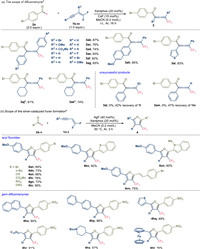

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we subsequently examined the scope of the 1, 4-acylfluorination reaction (Schemes 1 and 2). As acyl fluorides are accessible from the corresponding acyl chlorides or carboxylic acids, we directly mixed 4-bromobenzoyl chloride (5a), cesium fluoride, gem-difluoroenyne (1a) and the phosphine catalyst and we afforded allenone 3aa in 95% yield. With regard to acyl chlorides, halogen groups such as chloro (3ba) and iodo (3ca) were compatible. n-Butyl substituted benzoyl chloride (3da) can be converted to the product in moderate yield. Electron-deficient substrates bearing cyano (3ea), methoxycarbonyl (3fa), trifluoromethyl (3ga) and nitro (3ha) groups readily participated in this reaction. The reaction with electron-neutral benzoyl fluoride can afford the allenone 3ia in 52% yield on gram scale. Acyl chlorides bearing a heteroaryl (3ja, 3ka) group also underwent the acylfluorination successfully. A series of acyl fluorides were isolated and applied to acylfluorination (Scheme 1b). In the cases of aromatic carboxylic acids, the reaction of m-methoxy (3la), p-methoxy (3ma) benzoic acid and 7-quinolinecarboxylic acid (3na) proceeded efficiently. Notably, unstable aliphatic acyl fluorides were also compatible and moderate yields of the corresponding allenones (3oa, 3qa) can be obtained. This protocol can be used in the late-stage functionalization of pharmaceuticals, as shown by the reactions of probenecid, bexarotene, lumacaftor intermediate and febuxostat (3pa-3sa). We subsequently explored the scope of gem-difluoroenynes using 4-bromobenzoyl fluoride (Scheme 2a). The difluoroenynes bearing either electron-deficient or electron-rich groups can participate in the acylfluorination to produce the corresponding allenones (3ab-3ag). Various alkynyl substituents such as methoxynaphthyl (3ah), thienyl (3ai), cyclohexyl (3aj) and cyclohexenyl (3ak) can be introduced into allenone molecules.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Scope of the acylfluorination of enynes (scope of acyl sources). a The reaction was carried out in one step on 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are for the isolated products. b The reaction was carried out on 10.0 mmol scale. c The reaction was carried out in two steps on 0.2 mmol scale. Acyl fluorides were purified by short silica gel in the first step. d Cesium fluoride was replaced by silver fluoride. | |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Scope of the acylfluorination of enynes (scope of difluoroenynes). a The reaction was carried out on 0.2 mmol scale with purified acyl fluoride. b Cesium fluoride was replaced by silver fluoride. | |

With the alkyl group or hydrogen in 2-position of gem-difluoroenyne, the corresponding allenone products 3al and 3am were not obtained under the standard conditions (cesium fluoride and Xantphos). However, when switching to silver fluoride, a small amount of furan product (6%) was observed in the reaction mixture. This is in line with our initial hypothesis that silver fluoride could promote the 1, 2-addition of enynes and intramolecular annulation to afford trifluoromethylated furans (Fig. 1d). We subsequently attempted to optimize the catalylic condition of this 1, 2-acylfluorination. The reaction cannot proceed in the absence of silver fluoride and the addition of 20 mol% phosphine promoted the reaction. But the excess amount of the phosphine would interfere with the enyne and detriment the furan formation. After screening the amount of catalyst loading and reaction temperature, 72% yield of furan 4gn can be acheived with 40 mol% of silver fluoride and 20 mol% of Xantphos at 50 ℃ (for details see Table S3 in Supporting information).

Subsequently, we explored the scope within the modified conditions for furan formations (Scheme 2b). The protocol demonstrated versatility across various types of acyl fluorides. Benzoyl fluorides featuring bromo (4an), n-butyl (4dn), cyan (4en), methoxycarbonyl (4fn), nitro (4gn), and benzyloxy (4tn) substituents were amenable to the process. Furthermore, heteroaromatic acyl fluorides exhibited successful 1, 2-acylfluorination, yielding a pathway to synthesize benzothiazole and indole-substituted furans (4kn, 4un). The applicability of the acylfluorination strategy extended to cinnamic acid-derived acyl fluoride, resulting in the isolation of alkenylfuran 4vn with a satisfactory yield of 75%. The versatility of the method was also evident in the context of difluoroenyne substrates. Difluoroenynes bearing π-extended aryl motifs yielded the desired products (4ho, 4hp) in elevated yields. While moderate yields were achieved with thienyl-substituted difluoroenyne (4hq), the transformation remained viable. Moreover, the method was capable of introducing aliphatic groups, such as decyl (4hr) and piperidinyl (4hs), into furan structures with commendable efficiency. Notably, the process accommodated the presence of ferrocene substitution within the difluoroenyne scaffold, underscoring the method's utility in furnishing furyl-substituted ferrocene derivatives (4ht) in a controlled manner.

Based on the experiments, a proposed catalytic cycle is depicted in Scheme 3. In instances where the gem-difluoroenyne (1) bears an aryl substituent in 2-position, the phosphine undergoes addition to the electron-deficient triple bond, yielding the β-phosphonium α-carbanion species (int1). Subsequent nucleophilic substitution between the carbanion and the acyl fluoride leads to the formation of an acylated phosphonium species (int2) with a conjugated structure. The electrophilicity of the system facilitates fluoride ion addition to the difluoromethylene group, resulting in the formation of the allenone product 3. When the substituent of 2-position in the gem-difluoroenyne 1 is hydrogen, the compound undergoes initial fluorination mediated by the silver fluoride catalyst. The control experiments suggested that a stable coordination between silver, alkyne and carbonyl that facilitates the acylation of difluoroalkenes and subsequent cyclization (Schemes S2 and S3 in Supporting information). The ensuing propargyl silver species (int3) reacts with the acyl fluoride to generate int4 and then it will transfer to an alkynyl-coordinated silver enolate (int5), accompanied by elimination of hydrogen fluoride. Subsequent migration insertion precipitates the formation of a silver furanate (int6). Acidification of the silver furanate with hydrogen fluoride regenerates the silver fluoride catalyst, liberating the furan product (4).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. A possible catalytic cycle. | |

In conclusion, we have presented a method for acylfluorination of gem-difluoroenynes via phosphine and silver catalysis with acyl fluoride as both acyl and fluorine source. Selective phosphine-catalyzed 1, 4-addition furnishes a diverse array of CF3-substituted allenones. Silver-catalyzed 1, 2-addition furans and intramolecular cyclization gives CF3-substituted furans. Further research of fluorinated compounds is underway in our laboratory.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsWe gratefully acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21971107, 22071101, and 22271147).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109443.

| [1] |

Q. Dherbassy, S. Manna, F.J.T. Talbot, et al., Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 11380-11393. DOI:10.1039/d0sc04012f |

| [2] |

L. Fu, S. Greßies, P. Chen, G. Liu, Chin. J. Chem. 38 (2020) 91-100. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.201900277 |

| [3] |

Y. Zhou, Y. Zhang, J. Wang, Org. Biomol. Chem. 14 (2016) 6638-6650. DOI:10.1039/C6OB00944A |

| [4] |

S. Li, W. Yang, J. Shi, et al., ACS Catal. 13 (2023) 2142-2148. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c04978 |

| [5] |

F.D. Lu, L.Q. Lu, G.F. He, J.C. Bai, W.J. Xiao, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 4168-4173. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c01260 |

| [6] |

S. Manna, Q. Dherbassy, G.J.P. Perry, D.J. Procter, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 4879-4882. DOI:10.1002/anie.201915191 |

| [7] |

L. Lv, L. Yu, Z. Qiu, C. Li, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 6466-6472. DOI:10.1002/anie.201915875 |

| [8] |

Y. Zhou, L. Zhou, L.T. Jesikiewicz, P. Liu, S.L. Buchwald, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 9908-9914. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c03859 |

| [9] |

Y. Hu, Z. Zhang, Y. Liu, W. Zhang, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 16989-16993. DOI:10.1002/anie.202106566 |

| [10] | |

| [11] | |

| [12] |

J. Bégué, D. Bonnet-Delpon, Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry of Fluorine. 1st ed.. Wiley, 2008.

|

| [13] |

Nat. Prod. Rep. 17 (2000) 621-631. DOI:10.1039/a707503k |

| [14] |

Chem. Soc. Rev. 37 (2008) 320-330. DOI:10.1039/B610213C |

| [15] |

Chem. Soc. Rev. 37 (2008) 1727-1739. DOI:10.1039/b800310f |

| [16] |

Progress Polym. Sci. 35 (2010) 1022-1077. DOI:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2010.04.003 |

| [17] |

J. Fluorine Chem. 100 (1999) 127-133. DOI:10.1016/S0022-1139(99)00201-8 |

| [18] |

Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 650-682. DOI:10.1021/cr500223h |

| [19] |

Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 1513-1522. DOI:10.1021/ar4003202 |

| [20] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 8294-8308. DOI:10.1002/anie.201309260 |

| [21] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 8950-8958. DOI:10.1002/anie.201202624 |

| [22] |

Chem. Rev. 111 (2011) 4475-4521. DOI:10.1021/cr1004293 |

| [23] |

Synthesis (2003) 0185-0194. DOI:10.1055/s-2003-36812 |

| [24] |

Chem. Rev. 97 (1997) 757-786. DOI:10.1021/cr9408991 |

| [25] |

Chem. Commun. 58 (2022) 10442-10468. DOI:10.1039/d2cc04082d |

| [26] |

Org. Chem. Front. 9 (2022) 1152-1164. DOI:10.1039/D1QO01504D |

| [27] |

Chem. Eur. J. 21 (2015) 7648-7661. DOI:10.1002/chem.201406432 |

| [28] |

Org. Lett. 17 (2015) 2474-2477. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b00980 |

| [29] |

Org. Lett. 18 (2016) 5688-5691. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02919 |

| [30] |

J. Fluorine Chem. 268 (2023) 110111. DOI:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2023.110111 |

| [31] |

Org. Lett. 21 (2019) 671-674. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03841 |

| [32] |

J. Fluorine Chem. 196 (2017) 67-71. DOI:10.1016/j.jfluchem.2016.08.014 |

| [33] |

Tetrahedron Lett. 51 (2010) 6150-6152. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.09.068 |

| [34] |

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 15869-15872. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b11205 |

| [35] |

Chem. Eur. J. 26 (2020) 1953-1957. DOI:10.1002/chem.201905445 |

| [36] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 3918-3922. DOI:10.1002/anie.201814308 |

| [37] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 6772-6775. DOI:10.1002/anie.201902779 |

| [38] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 638-642. DOI:10.1002/anie.201409705 |

| [39] |

Org. Lett. 16 (2014) 102-105. DOI:10.1021/ol403083e |

| [40] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 9872-9876. DOI:10.1002/anie.201705321 |

| [41] |

ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 205-210. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b03999 |

| [42] |

Org. Lett. 22 (2020) 5229-5234. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01887 |

| [43] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 22957-22962. DOI:10.1002/anie.202008262 |

| [44] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 574-594. DOI:10.1002/anie.201902805 |

| [45] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 6814-6817. DOI:10.1002/anie.201900591 |

| [46] |

ACS Catal. 7 (2017) 8200-8204. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.7b02938 |

| [47] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202303657. DOI:10.1002/anie.202303657 |

| [48] |

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 18394-18399. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c10042 |

| [49] |

ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 15241-15248. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c04970 |

| [50] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202303222. DOI:10.1002/anie.202303222 |

| [51] |

Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 25252-25257. DOI:10.1002/anie.202110304 |

| [52] |

Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 2068. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-22292-z |

| [53] |

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 4903-4909. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c01022 |

| [54] |

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 17323-17328. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c08928 |

| [55] |

Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 10049-10293. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00081 |

| [56] |

J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (2008) 4610-4617. DOI:10.1021/ja071316a |

| [57] |

Org. Lett. 18 (2016) 1706-1709. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00677 |

| [58] |

Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 7382-7384. DOI:10.1039/c4cc02800g |

| [59] |

Org. Lett. 25 (2023) 726-731. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c04082 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35