b PETRONAS Carbon Capture & Storage (CCS) Enterprise, PETRONAS Twin Towers, Kuala Lumpur City Centre, Kuala Lumpur 50088, Malaysia;

c CO2 Research Center (CO2RES), Department of Chemical Engineering, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar 32610, Malaysia;

d Department of Chemical Engineering and Energy Sustainability, Faculty of Engineering, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), Kota Samarahan 94300, Malaysia;

e Institute of Sustainable and Renewable Energy (ISuRE), Universiti Malaysia Sarawak (UNIMAS), Kota Samarahan 94300, Malaysia;

f Higher Institution Centre of Excellence (HICoE), Institute of Tropical Aquaculture and Fisheries (AKUATROP), Universiti Malaysia Terengganu, Kuala Nerus 21030, Malaysia;

g Co-Innovation Center of Efficient Processing and Utilization of Forest Resources, College of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China;

h Center for Global Health Research (CGHR), Saveetha Medical College, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Chennai 602105, India

Hydrogen (H2) is a carbon-free fuel and energy source that is perceived as a novel substitute to many fossil-based derivatives in the effort to attain net zero carbon emission and align with the sustainable development goals (SDGs). H2 and syngas have been conventionally produced from steam methane reforming (SMR), partial oxidation (POX) and coal gasification reactions [1]. SMR process involves the endothermic reaction of steam and methane to produce syngas (H2 and CO), whereas POX involves the use of sub-stoichiometric oxygen conditions to partially oxidize methane/hydrocarbons into syngas [2]. On the other hand, instead of using gaseous hydrocarbons as feedstock, coal gasification converts carbonaceous solid coal to syngas via reactions with steam, air, oxygen or CO2 [3]. However, these processes are associated with high carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and not sustainable. In view of this, cleaner H2 production routes and feedstocks are urgently demanding researchers' attention. To decarbonize the H2 production process, both feedstock and technology play pivotal role.

Various alternative H2 production routes have been developed, including electrolysis, thermochemical, biological, photocatalysis, photoelectrochemical [4,5], and a variety of feedstocks have been explored for circular H2 economy, mainly wastes such as plastics, municipal solid wastes, biomass wastes, food wastes, and sludge [6]. Water electrolysis is the cleanest way of generating green H2 powered by renewable energies such as solar and wind [7,8]. Since its discovery around the end of 18th century, the technology has seen continuous development. Commercial plants were built in 20th century to meet the huge H2 demand for ammonia fertilizers production, until a few cheaper methods of large-scale H2 production from hydrocarbon came into picture [9]. As a result, only 2% of world H2 production comes from water electrolysis today [10]. New systems such as proton exchange membrane (PEM) and solid oxide electrolysis cell (SOEC) have been developed to deliver a more cost-effective solution. Nevertheless, the current cost of electrolyzer and renewable energy is still not low enough to bridge the gap between H2 from water electrolysis and that from hydrocarbon. Depending on region, the levelized cost of H2 (LCOH) produced from natural gas (NG) is in the range of USD 0.50–1.70/kg H2, while the LCOH produced from renewable energies is much costlier in most places, at USD 3.00–8.00/kg H2 [11]. Consequently, there is clearly little economic motivation to produce H2 from renewable energies at this point of time. Other than methane, water and hydrocarbons, ammonia (NH3) is also a good carrier of H2 [12], in which recent studies have begun to investigate the decomposition/cracking of ammonia [13] or ammonium-based compounds [14] as alternative H2 production technology. Apart from that, conversion of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a hazardous industrial gas, into H2 is also currently gaining research attention [15].

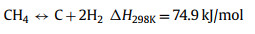

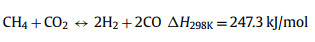

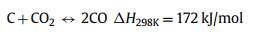

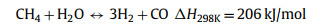

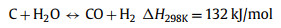

Thermal decomposition of methane (TDM), also known as methane (CH4) pyrolysis/cracking for turquoise H2 production might be the step-change approach for the transition of grey H2 to green H2 [16,17]. It is a thermal decomposition process that produces only H2 and solid carbon from CH4 (Eq. 1). Generally, this approach eliminates the emission of CO2, consequently avoiding the energy intensive and costly carbon capture process. In the case of presence of impurities in the feedstock (methane), such as CO2, O2, H2O, side reactions such as dry methane reforming (Eq. 2), partial oxidation of carbon produced from methane decomposition (Eq. 3), steam methane reforming (Eq. 4) and water gas reaction, i.e., reaction between H2O with the carbon produced from methane cracking (Eq. 5) might occur and alter the overall reaction equilibrium, resulting in varied composition of the gas product. Compared to water electrolysis, TDM uses ~7.6 fold less energy requirement (37.5 kJ/mol H2 via TDM vs. 286.0 kJ/mol H2 via electrolysis) [18]. The earliest commercial application of TDM was the production of solid carbonaceous materials such as synthetic graphite, channel black and electrode [19]. While realizing its role and potential in low-carbon H2 production, CH4 pyrolysis technology is recently attracting attention from both research institutes and businesses. Preliminary studies have pointed out that CO2 footprint mitigation of about ~40% to ~80% could be achieved by CH4 pyrolysis technology as compared to the state-of-the-art SMR [20,21].

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

Generally, TDM can be performed in various reactor configurations or concepts, such as fixed bed, fluidized bed, moving bed, plasma/microwave/solar-assisted, and molten metal/salt. Several key industrial/corporate players that have been leading the development and scaling-up/piloting of the technology are C-Zero (molten catalyst reactor) [22], MONOLITH (plasma reactor) [23], Hazer (fluidized bed catalytic reactor) and BASF (moving bed reactor) [24]. Raza et al. [25] conducted a thorough review specifically on the performance/efficiency and pros/cons of various catalysts and reactor configurations on the CH4 pyrolysis process. Besides, Banu and Bicer [26] and Fan et al. [27] presented comprehensive analyses focusing on the potential of metal-based, carbon-based and liquid catalysts in pyrolysis reactions. Another review article by Karimi et al. [28] concentrated on the efficacy of metallic promoters in Ni-based catalysts for H2 production via CH4 pyrolysis. These review articles covered and evaluated extensively the role and performance of various catalysts in different reactor configurations, however, systematic and detailed analysis on the effect of process/operating parameters on the pyrolysis reaction (e.g., CH4 conversion, H2 yield and selectivity) are still lacking. In addition, to the authors' best knowledge, critical review on the techno-economic analysis (TEA) of CH4 pyrolysis process is still limited in the literature, albeit the route has been perceived a feasible solution for H2 production economically and ecologically.

As such, this review article aims to (1) assess fundamentally the current state-of-the-art with respect to the influence of key operating parameters on CH4 conversion and H2 yield/selectivity, (2) discuss critically the techno-economic facet associated with TDM, and lastly (3) identify the challenges and prospects of the technology towards successful commercialization. The review elements are divided into four main sections, i.e., Section 2 on bibliometric analysis of current literature related to CH4 pyrolysis, Sections 3 and 4 on effect of process parameters on H2 production (including temperature, pressure, gas flowrate and residence time), Section 5 on the TEA of TDM process, and Section 6 on the challenges and outlook of TDM towards commercial deployment for low-carbon H2 production. Finally, the review ends with a concluding remark shown in Section 7. This review focuses only on the production of H2 from TDM process, as for the other byproduct i.e., solid carbon, the subject requires separate extensive review and evaluation, hence it is beyond the scope of this review paper.

2. Bibliometric analysis of current literature on methane pyrolysisThe conversion of methane into hydrogen has been extensively studied. The most common methods used are steam reforming, dry reforming, partial oxidation with or without catalyst, autothermal reforming and plasma reforming, biological conversion [29,30]. Besides all these methods, methane pyrolysis is introduced as a new research direction as it promotes the production of CO2-free hydrogen [31]. Bibliometric analysis has been used to study the trend of research focusing on the methane conversion via pyrolysis method for the production of hydrogen gas and carbon black. A co-occurrence analysis was performed by extracting data from Scopus between 2013 and 2023, with keywords ("methane" OR "CH4" AND "pyrolysis" OR "decomposition" OR "cracking" AND "hydrogen" OR "H2" AND "carbon". Primary run in Scopus database returned 2817 documents. Exclusion criteria has been included to improve the reliability of the analysis, where peer-reviewed documents in English were considered. Besides that, only "article" and "review" were included for bibliometric analysis. As a result, a total of 2323 documents (2231 articles and 92 reviews) were selected for bibliometric analysis.

Fig. 1 shows the bibliometric map generated by VOSViewer using the data extracted from Scopus with selected keywords and a co-occurrence of author keyword. Four clusters were observed, representing that there were four research hotspots, including: (1) The quality of products yielded from methane conversion, (2) comparison between methods in the production of hydrogen from methane gas, (3) advancement in the pyrolysis technique for methane conversion and (4) the effect of catalyst in methane conversion. The number of papers published, and the research direction of methane conversion can be observed from 2013 to 2023 (Fig. 2). Fig. 2a shows the number of publications according to the year, and an increasing research interest in methane pyrolysis can be seen for the past 5 years. The research direction was focused on the conventional methane conversion method before the year of 2017 (Fig. 2b). The introduction of pyrolysis for methane conversion was started in the mid of 2018, focusing on the pyrolysis kinetics and the quality of hydrogen produced. When the pyrolysis method was established as a promising conversion method, advanced pyrolysis techniques involving microwave, catalyst and co-pyrolysis were introduced for methane conversion. The keyword "methane pyrolysis" was used in general after 2021, showing that pyrolysis has been established as a promising method for the production of low-carbon hydrogen from methane.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Bibliometric mapping of methane pyrolysis to produce low-carbon-hydrogen over the past 10 years (from 2013 to 2023) based on 2323 documents from Scopus. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Bibliometric analysis of the data extracted from Scopus with reference to the publication in the past 10 years (2013–2023): (a) The number of papers published in the past 10 years. (b) The co-occurrence of author keywords according to years. | |

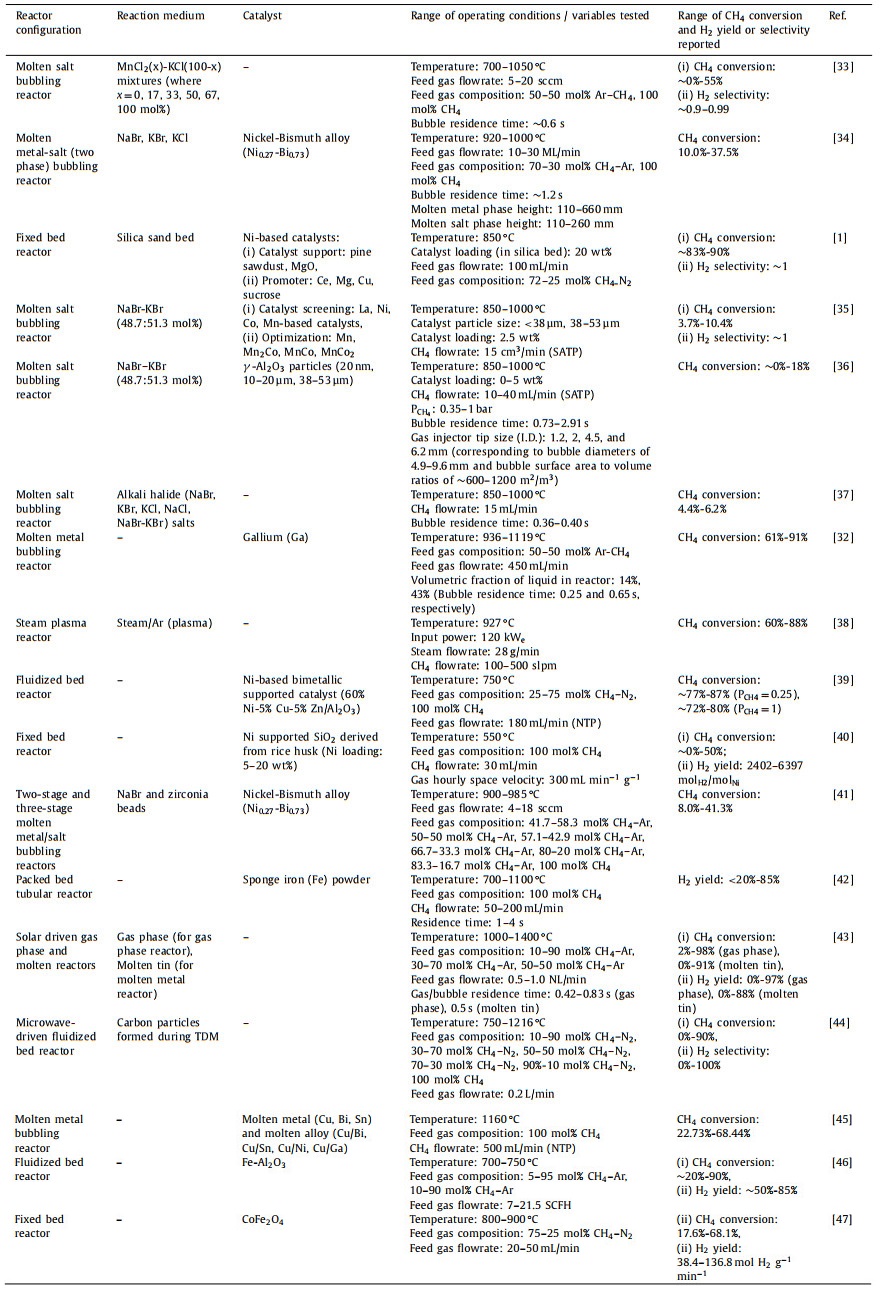

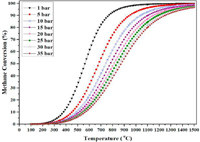

CH4 pyrolysis is a thermodynamically governed endothermic process preferably occurs at high temperature and low pressure. Based on the thermodynamic equilibrium of CH4 conversion (Fig. 3), temperature of > 750 ℃ is required to drive the equilibrium of the reaction to > 90% CH4 conversion at 1 bar. In accordance with Le Châtelier's principle, low pressure condition will drive the reaction (Eq. 1) forward towards the formation of H2. Other than temperature and pressure, there are also other several important operating parameters that influence the CH4 decomposition to H2, which are reviewed and discussed in detail in this section. Recent studies on TDM for H2 production, with the range of operating conditions/variables investigated are summarized in Table 1 [1,32-47].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Equilibrium conversion of CH4 to H2 and solid carbon at various temperatures and pressures. Reprinted with permission [32]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. | |

|

|

Table 1 Summary of recent TDM studies (from year 2019 to present) for turquoise H2 production from the literature. |

Temperature is a critical process parameter in the context of TDM due to endothermicity of the reaction. Typically, CH4 pyrolysis requires operation at high temperatures of 800–1400 ℃ [36]. As such, optimization of temperature in various catalytic and reactor systems of TDM is frequently investigated and reported. Generally, higher temperature increases the conversion of CH4 due to enhanced intrinsic kinetics and rate of CH4 thermal decomposition, and typically temperature above 900 ℃ (at 1 bar) is required to achieve CH4 conversion of above 90% [32]. Consistent trends were reported by several researchers, such as the highest CH4 conversion of 91% was observed at highest tested temperature of 1119 ℃ for CH4 pyrolysis in molten gallium [32] and the near zero CH4 conversion gradually increased to 4.4%–6.2% when the temperature was increased from 850 ℃ to 1000 ℃ in molten alkali halides (NaBr, NaCl, KBr, KCl, (Na, K)Br) salts [37]. Patzschke et al. [35] examined the pyrolysis of CH4 in molten NaBr—KBr with the presence of mixed Co-Mn catalysts (MnCo2/Al, MnCo/Al, Mn/Al) and reported that increase in temperature had a profound effect on the CH4 conversion, with a maximum CH4 conversion of 10.40% at 1000 ℃ for MnCo2/Al as compared to below 2% at 850 ℃. The optimization of reaction temperature is essential in CH4 pyrolysis as it would impact the conversion of CH4 and yield of H2, and thus the overall efficiency and economics of the process.

3.2. PressureCH4 pyrolysis is usually operated at relatively low and atmospheric pressure (below 5 bar) due to the equilibrium constraint of CH4 decomposition reaction. Based on Eq. 1 (1 mol of CH4 decomposes into 2 mol of H2 and 1 mol of carbon) and in accordance with the Le Châtelier's principle, low pressure will drive the reaction towards the formation of products [32]. As shown in Table 1, while most of the CH4 pyrolysis studies were performed at atmospheric pressure using pure CH4, several studies investigated the effect of CH4 partial pressure on its conversion. By diluting the CH4 feed with inert Ar (50–50 mol% CH4—Ar) and hence reducing the partial pressure of CH4 to shift the chemical equilibrium towards H2 production, Pérez et al. [32] and Kang et al. [33] reported high CH4 conversions of 91% and ~42% in molten gallium and MnCl2-KCl (67–33 mol%) mixture, respectively. Parkinson et al. [36] varied the partial pressure of CH4 between approximately 0.35 to 1 bar and observed that the rate of CH4 pyrolysis was linearly correlated to the CH4 partial pressure.

3.3. Gas flowrate/residence timeThe flowrate of feed gas would impact the residence time of the gas reactant in the reactor, and size of gas bubbles (in the case of molten metal or salt bubbling reactor), thus affecting its conversion. Kang et al. [33] varied the flowrate of CH4 in bubbling reactor between 5 sccm and 20 sccm and reported that relatively high conversion of CH4 was attained for lower CH4 flowrates at 1050 ℃. The authors ascribed this to the longer duration of bubble formation and growth at the tip of gas injector where the CH4 gas was in contact with the molten metal or salt, resulting in longer available time for the CH4 to react and decompose (as compared to the duration of the bubble rise through the molten reactor column). Similar trend was reported by Parkinson et al. [36] in which lower CH4 flowrates caused longer residence time in the molten reaction medium, hence leading to higher CH4 conversion (~17% conversion at 10 mL/min as opposed to ~12% conversion at 40 mL/min). However, after eliminating the effect of bubble rise velocity (by normalizing the conversion per unit residence time), it was still found that lower CH4 flowrates resulted in higher CH4 conversions [36]. This has led to an important note that aside from gas flowrate, there are various factors and parameters which will also collectively influence the residence time or bubble rise velocity (i.e., hydrodynamics) in molten bubbling reactors, such as depth of the molten column, density and viscosity of molten medium, and the bubble size [33]. In a study of CH4 pyrolysis using steam plasma conducted by Mašláni et al. [38], higher CH4 conversion of 88% was obtained at lower CH4 input flowrate (100 slm) as compared to 60% conversion at flowrate of 500 slm. Higher CH4 input flowrate resulted in higher H2 output from the reactor, but there was also higher amount of unreacted CH4, as evident from the energy balance of the reactor (insufficient energy of 10 kW and 38 kW for CH4 flowrates of 300 slm and 500 slm, respectively). As such, it is crucial to establish optimized input gas flowrate under various reactor configurations via extensive hydrodynamics studies [48].

3.4. OthersOther factors which affect CH4 decomposition include bubble size (specific surface area per unit volume), catalyst loading and catalyst particle size, and the composition (blending ratio) of molten binary-salt mixture. The effect of bubble size was thoroughly scrutinized by Parkinson et al. [36] by varying the diameter of the gas injector tip (1.2, 2, 4.5 and 6.2 mm I.D.). Smaller tip diameter produced bubbles with smaller equivalent diameter, and thus having higher gas-liquid interfacial area per unit volume (bubble size had two-fold impact on the CH4 conversion). This has elucidated the reaction mechanism of CH4 decomposition in molten metal/salt, i.e., CH4 reaction rate was dependent on the specific surface area of gas bubbles and gas phase reaction [36]. The dependence of reaction rate on gas-liquid interfacial area was also reflected in the work of Pérez et al. [32]. Using a porous gas distributor as the bubbles generator, enhanced CH4 conversions of 61%–91% were achieved as compared to that of single orifices (18% [49] and 32% [50]), even though the latter having significantly higher bubble residence time.

As the rate-limiting step for CH4 decomposition is the cleavage of the C—H bond, catalysts are often employed in CH4 pyrolysis process to aid in the activation of C—H bond. In this context, the catalyst loading and particle size might impact the kinetics of CH4 conversion and the endurance of the catalysts before deactivation due to carbon deposition on the catalyst active sites. Parkinson et al. [36] investigated the effects of γ-Al2O3 loading (0–5 wt%) and particle size (20 nm, 10–20 µm, 38–53 µm) on the conversion of CH4 in molten NaBr—KBr eutectic mixture. As the catalyst loading increased from 0 wt% to 5 wt%, the apparent activation energy of the reaction reduced from 246.9 kJ/mol to 128.4 kJ/mol. Besides, fine catalyst particles (20 nm) that were smaller than the effective film thickness of the bubble-liquid interface enhanced the mass transfer through liquid film surrounding the bubbles, resulting in relatively higher CH4 conversions over the entire range of temperature (800–1000 ℃) examined [36]. Similarly, higher CH4 conversions and lower activation energies were also reported for smaller particle size of Mn—Co-based catalysts (< 38 µm) as compared to that of larger particle size (38–53 µm) [35].

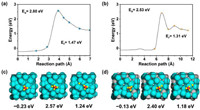

Lastly, for systems that employ molten binary-metal/salt/eutectic mixtures as the medium for CH4 pyrolysis, the blending ratio of the constituents could be influential on the kinetics of CH4 conversion. For example, Kang et al. [33] varied the blending ratio of MnCl2—KCl and noticed that the addition of MnCl2 (up to 50–67 mol%) improved the CH4 conversion and lowered the activation energy of the reaction (153–161 kJ/mol as compared to that of pure KCl (~300 kJ/mol) and pure MnCl2 (~175 kJ/mol). The addition of MnCl2 to KCl provided the synergy for CH4 decomposition as Mn is an effective element for C—H bond activation. Similarly, in the study conducted by Scheiblehner et al. [45] that assessed the mixing ratio of various binary metals, it was found that increasing content of Bi in Cu from 5 at% to 80 at% increased the CH4 conversion remarkably from ~39% to ~68% (as compared to ~33% CH4 conversion in pure Cu). The addition of Bi lowered the surface tension of the binary mixture, which in turn led to smaller bubble size. Besides, Fan et al. [27] also highlighted that the dissociation energy of CH4 on Cu-Bi catalyst is lower compared to that of Bi only (Fig. 4).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Ab initio molecular dynamics showing the methane dissociation energy on the surface of (a, c) Bi, and (b, d) Cu-Bi. Reprinted with permission [27]). Copyright 2021, Elsevier. | |

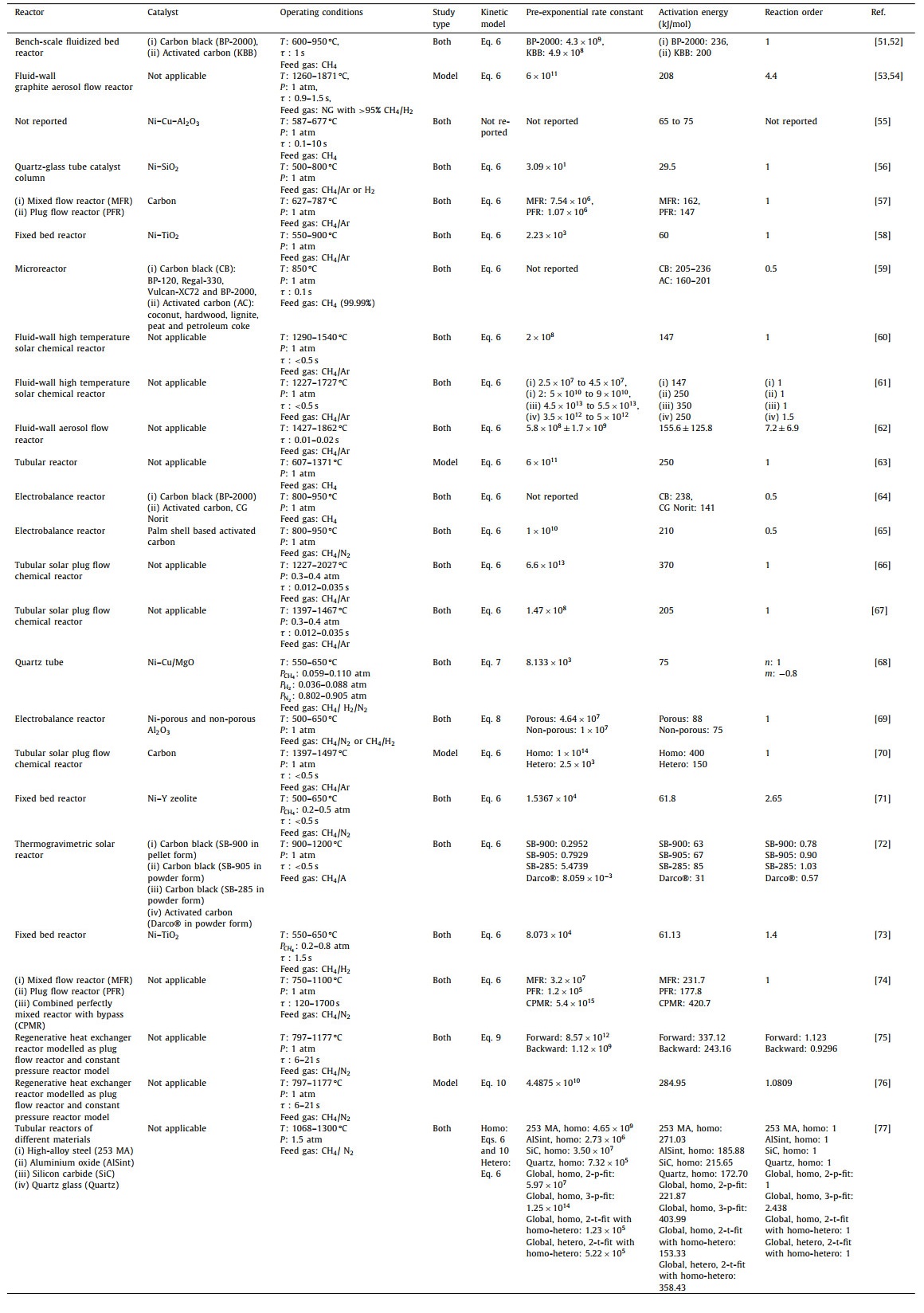

Extensive research has been conducted to elucidate the reaction of methane pyrolysis and to develop kinetic models for various reactor systems and catalysts used. Availability of the kinetic models provide valuable insights into the mechanisms, rates and activation energy that represents energy barrier that must be overcome for the reaction to occur. Kinetic models allow for the prediction and estimation of reaction rates under different conditions. By incorporating experimental data and theoretical principles, these models can provide information on the dependence of reaction rates on factors such as temperature, pressure, and reactant concentrations. In addition, by developing quantitative understanding on the kinetic parameters and its influence on reaction rates, researchers utilize the information for prediction of efficient methane pyrolysis processes, aiming to maximize hydrogen production. This knowledge helps in devising strategies to improve reactor design, catalyst performance, and process conditions, leading to more sustainable and economically viable methane pyrolysis processes. A comprehensive review of studies associated with determining the effect of reactor design, catalyst and operating conditions on the kinetic modelling and parameters have been summarized in Table 2 [51-77].

|

|

Table 2 Overview of kinetic studies on methane pyrolysis using various reactor types, catalysts and operating conditions. |

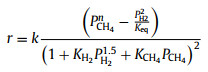

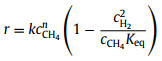

From the review, most authors were found to utilize the simple first order kinetic model in accordance to Eq. 6 [56-58,60,61,63,66,74] without consideration of chemical equilibrium, reverse reaction or deposition of unwanted carbon. Few studies also utilized Eq. 6 in the elementary form but deviated from the first order kinetic modelling by fitting reaction order to experimental data [53,54,59,60,62,64,65,71,73]. The equation was found to be appropriate and sufficient to characterize a wide range of methane thermal cracking process regardless of reactor configuration and catalyst design. The dependency of rate constant with temperature was commonly captured via Arrhenius relation. Subsequently, there were emerging efforts to develop extensions or deviations from the simple elementary kinetic modelling to take into account non-idealities and constraints from equilibrium, reverse reaction or decline in catalytic activity over recent years.

|

(6) |

where r is the reaction rate, k is the pre-exponential rate constant, cCH is the concentration of CH4, and n is the reaction order.

Borghei et al. [68] explained the reaction rates using Langmuir Hinshelwood mechanism and expressed them with respect to the partial pressures of both methane and hydrogen that corresponded to a power law equation, in which the presence of hydrogen had been reported to exhibit a negative order by reducing the overall reaction rate. In a study conducted by Keipi et al. [75], the adverse effects of hydrogen towards methane pyrolysis were analyzed using a simplified reverse kinetic mechanism. The parameters for this mechanism were determined through a global optimization approach. Notably, this methodology showed a more accurate alignment with experimental data as compared to a comprehensive 37-steps reaction mechanism proposed by Ozalp et al. [78], which was postulated to be caused by inaccuracy to predict solid carbon formation and temperature profile in the latter. Moreover, Amin et al. [69] developed kinetic model for methane catalytic cracking via utilization of a separable kinetics approach in order to develop initial rate and activity decay from catalyst deactivation. On the other hand, Catalan and Rezaei [76] formulated a thermodynamically consistent non-catalytic kinetic model to estimate decomposition rates of methane, particularly when approaching equilibrium conversions. A comprehensive model that incorporated several essential processes, including homogeneous nucleation of new particles, heterogeneous growth of both fresh and seed particles, particle coagulation, and the growth of carbon on the reactor walls due to heterogeneous reactions and particle deposition, was developed by [70]. Recently, kinetic parameters for describing the methane pyrolysis were determined both for each reactor with varying materials individually and globally using homogeneous reaction in the gas phase with a 1st and fitted orders via 2-p-fit and 3-p-fit, respectively, by Becker et al. [77]. Additionally, similar to study by Patrianakos et al. [70], the catalytic effect due to carbon formation was also incorporated via a novel heterogeneous surface mechanism of 1st order using a 2-t-fit model.

Kinetic models had been developed for different reactor systems in methane pyrolysis, which had been claimed to each offer distinct advantages and challenges. In terms of reactor design, some common systems include perfectly mixed flow [57,74], fixed bed [58,71,73], fluidized [51-54,60-62], thermogravimetric based [64,65,69,72] and the most popular tubular or tube or plug flow reactors [56,63,66-68,70,75-77]. Efficiency and performance comparison of different reactor models in characterizing the methane pyrolysis process had been studied by Trommer et al. [57] and Paxman et al. [74]. It was revealed that plug flow reactor model exhibited lower activation energy as compared to the perfectly mixed counterpart in general. The lower efficiency in perfectly mixed reactor was attributed to constraint in temperature and residence time distribution when dealing with reactions that had complex kinetics or involve multiple intermediate steps albeit less apparent impact as compared to catalyst selection and design. Paxman et al. [74] further proposed a Combined Perfectly Mixed Reactor with Bypass (CPMR) model with consideration of buoyancy flow to quantify kinetics and performance of the methane thermal decomposition, which was reported to enhance prediction accuracy. Other than the reactor configuration and operation, the kinetic study of reactors constructed from different materials, which included high-alloy steel (253 MA), aluminum oxide (AlSint), silicon carbide (SiC) and quartz glass (quartz) with calcium oxide (CaO) coating, was conducted in a recent study by Becker et al. [77], typically for the carbon deposition and removal characteristics. With regards to operating conditions, parameters such as temperature, pressure, and residence time, were revealed to be among the most detrimental factors that affected the kinetics. High temperatures were found to favor reaction kinetics and hence H2 production rates, but they also increased the propensity for carbon formation, leading to catalyst deactivation simultaneously. On the other hand, pressure and residence time had demonstrated varying effects on the reaction kinetics, depending on the catalyst used. Furthermore, energy sources to the reactors were found to vary and affect the kinetics, in which the utilization of electric furnaces and solar radiation were the most common facilities reported in the experimental setup from literature. In short, it was found that the reaction kinetics were highly complex and involve multiple intermediate species with the most common identified elementary reactions encompassed the dissociation of methane into methyl radicals and the subsequent decomposition of methyl radicals into hydrogen and other hydrocarbons. In this context, the materials, design, operating condition, and auxiliary facility were important factors that affected the kinetics of methane pyrolysis tremendously, which necessitated comprehensive study to develop a complete understanding.

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

In Eqs. 6–10, r is the reaction rate, k is the pre-exponential rate constant, cCH4 and pCH4 correspond to the concentration or partial pressure of methane reactant while cH2 and pH2 for hydrogen product, n and m represent the reaction order, Keq is the equilibrium constant while KCH4 and KH2 are the overall adsorption constants for methane and hydrogen, respectively.

From the review, it was found that kinetic study evolving methane pyrolysis had been conducted in the presence or absence of catalyst, with each carrying its discrete advantages. Catalysts could lower the reaction activation energy by providing an alternative pathway, reducing the energy barrier, which lowered the required operating temperature in the pyrolysis process [79]. These catalysts promoted the breaking of C—H bonds and facilitated the formation of hydrogen and carbon. On the contrary, although necessitating higher temperature in the absence of catalyst, it avoided operational issues associated to carbon deposition on the catalyst pellets, which caused deactivation and regeneration, that deteriorated the kinetics of hydrogen formation. All in all, the choice of catalyst was crucial for enhancing reaction kinetics and improving selectivity in methane pyrolysis [80]. Some commonly studied catalysts for methane pyrolysis included carbon based [51,52,57,64,65,70,72], transition metal typically from nickel (Ni) [56,58,59,69,71,73] due to its excellent sulfur resistance properties as compared to the other metals [81] and bimetallic types, which were postulated to modify the reaction activation energy and improve catalytic performance via optimization of the metal properties [55,68]. At large, the apparent activation energies associated with carbon-catalyzed methane decomposition exhibit a considerable range of variations, not only among different types of carbon, such as activated carbon (AC) and carbon black (CB), but also within the same carbon family. In general, for carbon catalyst, the AC-based was revealed to exhibit lower activation energies in the range of 141–201 kJ/mol as compared to carbon black of 205–238 kJ/mol, which was attributed to higher capability of AC based catalyst in expediating the reactions. An intriguing observation was that the activation energies for carbon-catalyzed methane decomposition fall within the range between the values of non-catalytic and metal-catalyzed reactions. Metal-based catalyst was found to be more efficient in lowering the activation energy by exhibiting activation energy in the range of 29.5–88 kJ/mol, while the non-catalyzed reactions were reported to exhibit wider variations between 147 kJ/mol and 420.7 kJ/mol, dependent upon the operating conditions and design. For the metal-based catalyst, supporting materials that were commonly used for methane pyrolysis included metal oxides, such as Al2O3 [55,69], SiO2 [56], TiO2 [58,73], MgO [68] and zeolites [71], which enhanced reaction kinetics by providing a larger active surface area.

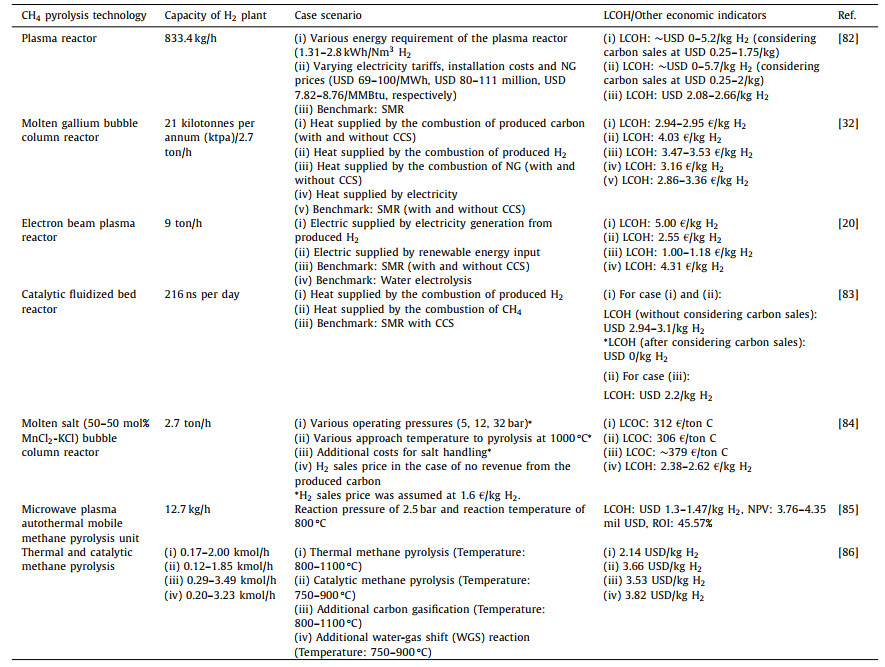

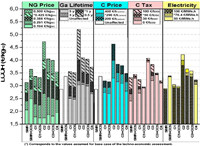

5. Techno-economic analysis (TEA) of methane pyrolysis processWhile it is proven that the production of H2 and carbon via CH4 pyrolysis is technically achievable, the successful deployment of this technology in commercial scales relies heavily on the economic performance and feasibility. Several techno-economic analysis (TEA) reports evaluating the economic feasibility and potential of CH4 pyrolysis are available, as summarized in Table 3 [20,32,82-86]. Pérez et al. [32] evaluated the techno-economic performance of an industrial concept of TDM operated in molten gallium bubble reactor. Considering various scenarios of heat supply for the pyrolysis reactor, i.e., (1) carbon combustion with and without CCS, (2) H2 combustion, (3) NG combustion with and without CCS and (4) electricity, In terms of LCOH, it was found that cases 1 (2.94 €/kg H2) and 4 (3.16 €/kg H2) were competitive as compared to the benchmark SMR process without CCS (2.86 €/kg H2), whereas case 2 registered the highest LCOH (4.03 €/kg H2) due to high throughput of NG to produce H2 for firing up the pyrolysis reactor and meet the H2 production capacity. However, considering the sustainability aspect, case 1 (with CCS) and 4 were environmentally superior while being economically competitive (lower CO2 emissions and carbon taxes) as compared to the established SMR process without CCS. The same study also explored the influence of several key parameters that would affect the LCOH through a detailed sensitivity analysis, as displayed in Fig. 5. Among these parameters, NG price and carbon sales price played decisive part in determining the economic feasibility of CH4 pyrolysis as opposed to conventional SMR process for H2 production.

|

|

Table 3 Summary of TEA on CH4 pyrolysis from the literature. |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Sensitivity analyses of the key parameters on the LCOH of CH4 pyrolysis for various case scenarios. Reprinted with permission [32]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. | |

Kerscher et al. [20] and Riley et al. [83] conducted TEA of TDM featuring different reactor configurations, namely electron beam plasma reactor and catalytic fluidized bed reactor, respectively. Nevertheless, similar case scenarios as that of Pérez et al. [32] were investigated, where the heat/electrical energy required for the pyrolysis was supplied by the produced H2 and alternate sources such as renewable energy or NG. For CH4 pyrolysis driven by electron beam plasma, the lowest LCOH was 2.55 €/kg H2, which was totally outweighed by the convention SMR process with and without CCS (1.00–1.18 €/kg H2), but was superior than that of water electrolysis (4.31 €/kg H2). High LCOH from water electrolysis process was attributed to the high specific energy requirement of splitting H2O molecules (286.0 kJ/mol H2) as compared to splitting CH4 molecules (37.5 kJ/mol H2). The study also revealed that the current expensive electron accelerators caused the process to be CAPEX-intensive and contributed to more than 50% of the LCOH. However, with the plasma technology gradually gaining maturity in the future, this could lower the overall CAPEX of the process and further reduce the LCOH to below 1.5 €/kg H2 [20]. In the work of Riley et al. [83], it was estimated that the LCOH from CH4 pyrolysis was in the range of USD 2.94–3.1/kg H2 assuming no profit from the generated carbon. On the other hand, if revenues were considered from the generated carbon, the LCOH could approach USD 0/kg H2. The effect of operating conditions for a molten salt bubble column reactor on the techno-economic performance of CH4 pyrolysis was explored by Pruvost et al. [84]. In contrary to most of the TEA studies, this study assumed a fixed H2 sales price (1.6 €/kg H2) to estimate the levelized cost of carbon (LCOC). At optimized operating pressure and approach temperature of 12 bar and 100 ℃, respectively, lowest LCOC of 306 €/ton was reached, and the LCOC was expected to increase 24% (to ~379 €/ton) after considering the post-pyrolysis treatment of the carbon [84].

Tabat et al. [85] proposed a mobile autothermal methane pyrolysis unit that addresses the limited availability of hydrogen pipeline infrastructure, demonstrating its profitability. The study evaluated the efficiency and performance of the integrated process through energy and exergy calculations. The economic analysis indicated a LCOH ranging from USD 1.3 to 1.47 per kg and a NPV between 3.76 mil and 4.35 mil. USD, influenced by factors such as EPC and feedstock cost. The positive NPV and lower LCOH demonstrated the profitability of the proposed design with a high methane conversion rate of 76.8%. Cheon et al. [86] provided a comprehensive analysis of various hydrogen production systems, evaluating their unit production costs and comparing them to commercialized methods. The technical performance of these systems was evaluated based on factors such as hydrogen and carbon production rates, hydrogen combustion ratio, and reactant ratios. The study determined unit hydrogen production costs of USD 2.14, 3.66, 3.53, and 3.82 per kilogram for different system configurations as shown in Table 3.

In short, as demonstrated by these TEA studies, the successful deployment of CH4 pyrolysis technology in the commercial scales relies heavily on the revenues of the co-generated carbon. To attain a comparable H2 price with the conventional SMR process, it is essential for the carbon product to have a promising market and hence the sales could render the whole pyrolysis technology economically viable. In addition, these studies also commonly pointed out that diversion of a portion of the produced H2 to sustain the pyrolysis reactor was uneconomical, as high volumes of NG were needed and the massive amount of carbon produced would require large market sizes and consumers.

6. Challenges and outlookTDM has emerged as a promising alternative for H2 production. From the review of current progress of the technology, a few key takeaways, challenges and outlook are summarized as follows:

(1) Catalyst poisoning or deactivation is one of the key technical and process challenges that needs to be attended. Generally, solid heterogeneous catalysts used in methane pyrolysis are faced with the risk of catalyst deactivation/coking due to deposition and formation of carbon particles that block the active sites of the catalysts [87]. This issue is seen to be potentially mitigated by using molten metals/salts. However, molten media reactors are associated with difficulties in the continuous removal of carbon, requiring delicate reactor design [22].

(2) The techno-economics remains the key challenge of TDM. For every kilogram of H2 produced, 3 kg of carbon is generated as a co-product. Hence it is vital to find diverse applications for these large volumes of solid carbon. One suggestion is to target high-value niche market in which high-purity carbon feedstock can command considerable price premium, such as carbon anodes, sorbents and graphite. Once pyrolysis carbon slowly penetrates the market and with increasing maturity over time, the LCOC from TDM will become more competitive, and applications can potentially become wider (metallurgy, chemicals, and energy sectors) when cheap supply of solid carbon is more abundant [84].

(3) For the carbon generated from TDM to meet the specifications for a variety of applications, further intensive R & D and process optimization needs to be done especially on minimizing the contamination of carbon (by molten salt/metal) and cost-effective ways of post-pyrolysis separation, purification, treatment and upgrading of carbon. Further economic advantages can also be achieved through discovery of novel and more catalytically active reaction medium to improve the CH4 conversion efficiency.

(4) TDM can be an alternative route to convert CO2 into solid carbon. Instead of directly converting CO2 into solid carbon for sequestration purpose, CO2 methanation can be carried out followed by CH4 pyrolysis. The solid carbon carries and stores large amount of energy, which can serve as a medium for large-scale permanent energy storage to be utilized in time of energy crisis.

(5) While producing H2 through CH4 or NG pyrolysis can be a viable way during the energy transition period, the long-term vision might be to apply this technology to plant-based methane or biomethane, to achieve negative carbon emission. This could be applicable to countries with abundant source of crop wastes. Through this, the economics can be supported not only by H2 and solid carbon sales, but also carbon credit sales to industries that are having difficulties to abate their large carbon emissions, such as steel and cement industries. Furthermore, integration of TDM process into these carbon-intensive industries could also be the way forward to decarbonization [88].

(6) Comprehensive cradle-to-grave life cycle assessment (LCA) studies are one of the significant challenges and crucial considerations for establishing a sustainable low-carbon hydrogen economy. The accuracy of these assessments is impeded by limited access to and reliability of data, particularly concerning process parameters, energy inputs, emissions, and economic factors. Moreover, the acquisition of experimental data and the development of predictive models present ongoing difficulties. To evaluate the long-term sustainability and feasibility of methane pyrolysis, it is imperative to take into account policy frameworks and market dynamics, such as supportive regulations and evolving market demands. Overcoming challenges related to data availability, the integration of process parameters and reaction kinetics, techno-economic analysis, scale-up, and policy dynamics will bolster the dependability and utility of LCAs for methane pyrolysis in low-carbon hydrogen production. Such assessments will furnish decision-makers and stakeholders with valuable insights to navigate the transition toward a sustainable hydrogen economy, while considering both the economic viability and environmental impact.

7. ConclusionsCH4 pyrolysis as an alternative route for turquoise H2 production has exhibited some promising feasibility in lab-scale experimentations. Compared to the conventional SMR process for producing grey H2, the associated carbon footprint of H2 from TDM can be near-zero. Besides, TDM is also less energy intensive as opposed to water electrolysis (green H2), making it a competitive technology for H2 production. Based on the literature review conducted, much of the recent works are still at the lab-scale exploratory stage, focusing on the optimization of process parameters and selection of efficient and cost-effective reaction media (molten metal/salt) and catalysts to enhance CH4 conversion kinetics in various reactor configurations (liquid bubbling reactor, catalytic fluidized bed, plasma reactor). Various TEA studies also revealed that the key element in determining the economic feasibility of TDM is the potential sales of the generated carbon product, which could be a showstopper to successful industrial deployment of the technology.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors acknowledge the financial support by the Education University of Hong Kong to perform this project under International Grant (UMT/International Grant/2020/53376). The authors fully appreciate the support and permission from the head of all organizations to publish the findings. The authors would also like to thank Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences for the facilities and support provided.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109329.

| [1] |

J. Zhang, M. Ren, X. Li, et al., Energy Convers. Manag. 205 (2020) 112419. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112419 |

| [2] |

S.C. Dantas, J.C. Escritori, R.R. Soares, C.E. Hori, Chem. Eng. J. 156 (2010) 380-387. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2009.10.047 |

| [3] |

Z. Chen, Q. Dun, Y. Shi, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 316 (2017) 842-849. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2017.02.025 |

| [4] |

V. Madadi Avargani, S. Zendehboudi, N.M. Cata Saady, M.B. Dusseault, Energy Convers. Manag. 269 (2022) 115927. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2022.115927 |

| [5] |

H. Wu, M. Wang, F. Jing, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1983-1987. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.095 |

| [6] |

B.D. Catumba, M.B. Sales, P.T. Borges, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 7975-7992. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.11.215 |

| [7] |

C. Cheng, L. Hughes, J. Clean. Prod. 391 (2023) 136223. DOI:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136223 |

| [8] |

M. Du, D. Li, S. Liu, J. Yan, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 108156. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108156 |

| [9] |

D.M. Santos, C.A. Sequeira, J.L.J.Q.N. Figueiredo, J. Quím. Nova 36 (2013) 1176-1193. DOI:10.1590/S0100-40422013000800017 |

| [10] |

IEAThe Future of Hydrogen: Seizing Today's Opportunities, IEA, Paris, 2019.

|

| [11] |

IEAGlobal Hydrogen Review, France, 2021.

|

| [12] |

M. Asif, S. Sidra Bibi, S. Ahmed, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 473 (2023) 145381. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.145381 |

| [13] |

S.J. Kim, T.S. Nguyen, J. Mahmood, C.T. Yavuz, Chem. Eng. J. 463 (2023) 142474. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.142474 |

| [14] |

A.C. Gangal, R. Edla, K. Iyer, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 37 (2012) 3712-3718. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.04.011 |

| [15] |

Y.H. Chan, A.C.M. Loy, K.W. Cheah, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 458 (2023) 141398. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.141398 |

| [16] |

J. Diab, L. Fulcheri, V. Hessel, V. Rohani, M. Frenklach, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47 (2022) 25831-25848. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.05.299 |

| [17] |

L. Weger, A. Abánades, T. Butler, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42 (2017) 720-731. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.11.029 |

| [18] |

S. Shiva Kumar, H. Lim, Energy Rep. 8 (2022) 13793-13813. DOI:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.10.127 |

| [19] |

T. Marquardt, A. Bode, S. Kabelac, Energy Convers. Manag. 221 (2020) 113125. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2020.113125 |

| [20] |

F. Kerscher, A. Stary, S. Gleis, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 19897-19912. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.03.114 |

| [21] |

S. Postels, A. Abánades, N. von der Assen, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 41 (2016) 23204-23212. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.09.167 |

| [22] |

M. McConnachie, M. Konarova, S. Smart, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 25660-25682. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.03.123 |

| [23] |

L. Fulcheri, V.J. Rohani, E. Wyse, N. Hardman, E. Dames, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 2920-2928. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.10.144 |

| [24] |

S. Schneider, S. Bajohr, F. Graf, T. Kolb, ChemBioEng Rev. 7 (2020) 150-158. DOI:10.1002/cben.202000014 |

| [25] |

J. Raza, A.H. Khoja, M. Anwar, et al., Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 168 (2022) 112774. DOI:10.1016/j.rser.2022.112774 |

| [26] |

A. Banu, Y. Bicer, Energy Convers. Manag.: X 12 (2021) 100117. |

| [27] |

Z. Fan, W. Weng, J. Zhou, D. Gu, W. Xiao, J. Energy Chem. 58 (2021) 415-430. DOI:10.1016/j.jechem.2020.10.049 |

| [28] |

S. Karimi, F. Bibak, F. Meshkani, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 20435-20480. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.03.160 |

| [29] |

L. Chen, Z. Qi, S. Zhang, J. Su, G.A. Somorjai, Catalysts 10 (2020) 858. DOI:10.3390/catal10080858 |

| [30] |

Z. Yang, Q. Zhang, H. Song, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. (2023) 108418. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108418) |

| [31] |

N. Sánchez-Bastardo, R. Schlögl, H. Ruland, Chem. Ing. Tech. 92 (2020) 1596-1609. DOI:10.1002/cite.202000029 |

| [32] |

B.J.L. Pérez, J.A.M. Jiménez, R. Bhardwaj, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 4917-4935. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.11.079 |

| [33] |

D. Kang, N. Rahimi, M.J. Gordon, H. Metiu, E.W. McFarland, Appl. Catal. B 254 (2019) 659-666. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2019.05.026 |

| [34] |

N. Rahimi, D. Kang, J. Gelinas, et al., Carbon 151 (2019) 181-191. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2019.05.041 |

| [35] |

C.F. Patzschke, B. Parkinson, J.J. Willis, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 414 (2021) 128730. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.128730 |

| [36] |

B. Parkinson, C.F. Patzschke, D. Nikolis, S. Raman, K. Hellgardt, Chem. Eng. J. 417 (2021) 127407. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.127407 |

| [37] |

B. Parkinson, C.F. Patzschke, D. Nikolis, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 6225-6238. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.11.150 |

| [38] |

A. Mašláni, M. Hrabovský, P. Křenek, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 1605-1614. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.10.105 |

| [39] |

K.R. Parmar, K.K. Pant, S. Roy, Energy Convers. Manag. 232 (2021) 113893. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.113893 |

| [40] |

K. Manasa, G. Naresh, M. Kalpana, et al., J. Energy Inst. 99 (2021) 73-81. DOI:10.1016/j.joei.2021.08.005 |

| [41] |

Y.G. Noh, Y.J. Lee, J. Kim, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 428 (2022) 131095. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131095 |

| [42] |

M.S. Vlaskin, A.V. Grigorenko, A.A. Gromov, et al., Results Eng. 15 (2022) 100598. DOI:10.1016/j.rineng.2022.100598 |

| [43] |

M. Msheik, S. Rodat, S. Abanades, Energy 260 (2022) 124943. DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124943 |

| [44] |

M. Dadsetan, M.F. Khan, M. Salakhi, E.R. Bobicki, M.J. Thomson, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 14565-14576. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.12.353 |

| [45] |

D. Scheiblehner, D. Neuschitzer, S. Wibner, A. Sprung, H. Antrekowitsch, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 6233-6243. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.08.115 |

| [46] |

R. Siriwardane, J. Riley, C. Atallah, M. Bobek, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 14210-14225. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.12.268 |

| [47] |

A.I. Alharthi, E. Abdel–Fattah, M.A. Alotaibi, I. Ud Din, A.A. Nassar, J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 27 (2023) 101641. DOI:10.1016/j.jscs.2023.101641 |

| [48] |

L.J.J. Catalan, E. Rezaei, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47 (2022) 7547-7568. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.12.089 |

| [49] |

M. Plevan, T. Geißler, A. Abánades, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 40 (2015) 8020-8033. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.04.062 |

| [50] |

T. Geißler, M. Plevan, A. Abánades, et al., Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 40 (2015) 14134-14146. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.08.102 |

| [51] |

N. Muradov, Thermocatalytic CO2-free production of hydrogen from hydrocarbon fuels, in: Proceedings of the 2000 Hydrogen Program Review, NREL/CP-570-28890, Florida, 2000.

|

| [52] |

N. Muradov, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 26 (2001) 1165-1175. DOI:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00073-8 |

| [53] |

J.K. Dahl, V.H. Barocas, D.E. Clough, A.W. Weimer, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 27 (2002) 377-386. DOI:10.1016/S0360-3199(01)00140-9 |

| [54] |

J.K. Dahl, A.W. Weimer, W.B. Krantz, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 29 (2004) 57-65. DOI:10.1016/S0360-3199(03)00046-6 |

| [55] |

T.V. Reshetenko, L.B. Avdeeva, Z.R. Ismagilov, A.L. Chuvilin, V.A. Ushakov, Appl. Catal. A: Gen. 247 (2003) 51-63. DOI:10.1016/S0926-860X(03)00080-2 |

| [56] |

S. Fukada, N. Nakamura, J. Monden, M. Nishikawa, J. Nucl. Mater. 329-333 (2004) 1365-1369. DOI:10.1016/j.jnucmat.2004.04.199 |

| [57] |

D. Trommer, D. Hirsch, A. Steinfeld, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 29 (2004) 627-633. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2003.07.001 |

| [58] |

S.H. Sharif Zein, A.R. Mohamed, P.S. Talpa Sai, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 43 (2004) 4864-4870. DOI:10.1021/ie034208f |

| [59] |

N. Muradov, F. Smith, A. T-Raissi, Catal. Today 102-103 (2005) 225-233. DOI:10.1016/j.cattod.2005.02.018 |

| [60] |

S. Abanades, G. Flamant, Sol. Energy 80 (2006) 1321-1332. DOI:10.1016/j.solener.2005.11.004 |

| [61] |

S. Abanades, G. Flamant, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 32 (2007) 1508-1515. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2006.10.038 |

| [62] |

J. Wyss, J. Martinek, M. Kerins, et al., Int. J. Chem. React. Eng. 5 (2007) A69. DOI:10.2202/1542-6580.1311 |

| [63] |

P. Homayonifar, Y. Saboohi, B. Firoozabadi, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 33 (2008) 7027-7038. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2008.09.007 |

| [64] |

J.L. Pinilla, I. Suelves, M.J. Lázaro, R. Moliner, Chem. Eng. J. 138 (2008) 301-306. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2007.05.056 |

| [65] |

H.F. Abbas, W.M.A. Wan Daud, Fuel Process. Technol. 90 (2009) 1167-1174. DOI:10.1016/j.fuproc.2009.05.024 |

| [66] |

S. Rodat, S. Abanades, J. Coulié, G. Flamant, Chem. Eng. J. 146 (2009) 120-127. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2008.09.008 |

| [67] |

S. Rodat, S. Abanades, J.L. Sans, G. Flamant, Sol. Energy 83 (2009) 1599-1610. DOI:10.1016/j.solener.2009.05.010 |

| [68] |

M. Borghei, R. Karimzadeh, A. Rashidi, N. Izadi, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 35 (2010) 9479-9488. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.05.072 |

| [69] |

A. Amin, W. Epling, E. Croiset, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 50 (2011) 12460-12470. DOI:10.1021/ie201194z |

| [70] |

G. Patrianakos, M. Kostoglou, A. Konstandopoulos, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 36 (2011) 189-202. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2010.09.061 |

| [71] |

M. Nasir Uddin, W.M.A. Wan Daud, H.F. Abbas, Energy Convers. Manag. 87 (2014) 796-809. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2014.07.072 |

| [72] |

S. Abanades, H. Kimura, H. Otsuka, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 40 (2015) 10744-10755. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.07.023 |

| [73] |

U.P.M. Ashik, W.M.A. Wan Daud, H.F. Abbas, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42 (2017) 938-952. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.09.025 |

| [74] |

D. Paxman, S. Trottier, M.R. Flynn, L. Kostiuk, M. Secanell, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 42 (2017) 25166-25184. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.08.134 |

| [75] |

T. Keipi, T. Li, T. Løvås, H. Tolvanen, J. Konttinen, Energy 135 (2017) 823-832. DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2017.06.176 |

| [76] |

L.J.J. Catalan, E. Rezaei, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45 (2020) 2486-2503. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2019.11.143 |

| [77] |

T. Becker, M. Richter, D.W. Agar, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48 (2023) 2112-2129. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2022.10.069 |

| [78] |

N. Ozalp, K. Ibrik, M. Al-Meer, Energy 55 (2013) 74-81. DOI:10.1016/j.energy.2013.02.022 |

| [79] |

S. Kazemi, S.M. Alavi, M. Rezaei, Fuel Process. Technol. 240 (2023) 107575. DOI:10.1016/j.fuproc.2022.107575 |

| [80] |

S. Kazemi, S.M. Alavi, M. Rezaei, E. Akbari, Fuel 342 (2023) 127797. DOI:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.127797 |

| [81] |

Q. Yan, T. Ketelboeter, Z. Cai, Molecules 27 (2022) 503. DOI:10.3390/molecules27020503 |

| [82] |

A.R. da Costa Labanca, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 45 (2020) 25698-25707. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.03.081 |

| [83] |

J. Riley, C. Atallah, R. Siriwardane, R. Stevens, Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 46 (2021) 20338-20358. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.03.151 |

| [84] |

F. Pruvost, S. Cloete, J. Hendrik Cloete, C. Dhoke, A. Zaabout, Energy Convers. Manag. 253 (2022) 115187. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2021.115187 |

| [85] |

M.E. Tabat, F.O. Omoarukhe, F. Güleç, et al., Energy Convers. Manag. 278 (2023) 116707. DOI:10.1016/j.enconman.2023.116707 |

| [86] |

S. Cheon, M. Byun, D. Lim, H. Lee, H. Lim, Energies 14 (2021) 6012. DOI:10.3390/en14196012 |

| [87] |

N. Sánchez-Bastardo, R. Schlögl, H. Ruland, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60 (2021) 11855-11881. DOI:10.1021/acs.iecr.1c01679 |

| [88] |

A. Bhaskar, M. Assadi, H.N. Somehsaraei, Energy Convers. Manag. X 10 (2021) 100079. |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35