b Innovation Laboratory for Sciences and Technologies of Energy Materials of Fujian Province (IKKEM), Xiamen 361102, China;

c Institute of Electromagnetics and Acoustics, School of Electronic Science and Engineering, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China

The lead halide perovskite (LHP) APbX3 (A = Cs+, MA+ and FA+; X = Cl–, Br–, and I–) has attracted attentions from various fields of optoelectronics [1-3]. The band-edge properties of LHP remains a hot topic with many problems remaining unclear, especially at cryogenic temperatures [4]. The band edge determines the peak photon energy of photoluminescence (PL), as well as absorption spectra (Abs.), in carrier recombination, while the interactions between carrier and lattice alter the band edge and, as a consequence, shapes of PLs and Abs. Therefore, information in PLs and Abs. are key to understanding the carrier and lattice dynamics. The processes of carrier excitation/injection and recombination includes the following steps in succession: (i) Generation of carriers; (ii) Relaxation until the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution with a certain carrier temperature Tc is established; (iii) Scattering with lattice and cooling to band-edge; (iv) Recombination. From Stage ii to Stage iii, Tc can be significantly higher than the temperature of lattice (Tl). Therefore, the carrier at these stages is usually called “hot carrier” (HC); and the Stage iii the “HC cooling”. It has been proven that the speed of HC relaxation is highly affected by the interaction between excitons and phonons. There are two routes of electron–phonon interaction through which the energy is transferred to the lattice. At room temperature interactions between electron and lattice are dominated by Fröhlich interaction, which is the interaction between electrons and longitudinal optics (LO) phonons, while at low temperature (<30 K), it turns into interactions between electron and longitudinal acoustic (LA) phonons of deformation-potential and piezoelectric interactions [5,6]. In the transient absorption spectroscopy (TAS), a transient redistribution of phonons among different states occurs right after excitation as it absorbs energy from HCs, but soon this excessive amount of energy is transferred from LO phonons to LA phonons. The energy dissipation rate in lattice depends on the density of state (DOS) of phonon, as high phonon DOS facilitates the downwards flow of energy from higher energy levels to lower ones, while the low DOS would result in hot phonons accumulation at LO branch, namely the hot phonon bottleneck (HPB) effect. The leading cause of HPB effect in APbX3 is the energy gap between LO and LA phonons [7-12].

In literature, the HPB effect was commonly observed in TAS, which provides a full map of carrier kinetics with femto-second resolution, in a manner of monitoring the change in absorption of material after it being excited. It reveals a slow decrease in Tc [7]. Despite the fact that the TAS becomes a typical method of investigating the HC cooling and HPB effect, the change in absorption do not in general reflect the dynamics in radiative recombination, i.e., time-resolved and steady-state photoluminescences (PLs). But the luminescence property is the ultimate goal of the entire investigation and the basis on which photonics engineering is conducted. A very recent report by Lim et al. proposed a research on modeling the steady-state PLs of a set of iodine perovskite, from which they extract Tc and demonstrate exceptionally low thermalization coefficients in these materials [13]. In some earlier reports concerning electron–phonon interactions, steady-state PLs have been studied in theory [5,14,15], and therefore, are employed as an indicator of carrier dynamics [9,16-18]. The temperature-dependent steady-state PLs are also employed in the application of thermometry [19].

Since recently, there have been reports on optically activated A4PbX6 [20-22], which was later identified as possessing a sort of APbX3@A4PbX6 core-shell structure. In this structure, the A4PbX6, where the PbX64+ octahedrons are detached to each other with Cs+ ions scattered in between, encapsulates the APbX3 QDs, forming a structure similar to the raisin bread (APbX3: raisin, A4PbX6: bread) [21,22]. The APbX3 QDs inside are responsible for the lumination. It was found that there exist large discrepancies in the TAS behaviors between CsPbBr3@Cs4PbBr6 complexes and CsPbBr3 QDs [11,20,23,24], which witness apparent contrasts. One group reported slower HC cooling in CsPbBr3@Cs4PbBr6 compared with in CsPbBr3 [24], whereas others reported the opposite [11,23]. However, the discrepancy actually is caused by the different excitation conditions. The former used the 310-nm laser which induces strong polaron density, while the latter two employed 400-nm excitation sources, of which the photon energy is not sufficient to excite Cs4PbBr6, thus no high electron–phonon interaction was induced. Despite these discrepancies, these works agreed on the fact that the contribution from LO phonons in Cs4PbBr6 shells and the phonon–phonon interaction across the CsPbBr3@Cs4PbBr6 interfaces provide additional routes for the heat dissipated from HC. Therefore, comparisons between APbX3@A4PbX6 and APbX3 would provide a new aspect for studying the HBP effect.

Hitherto, one problem concerning the thermodynamics during hot carrier relaxation under steady-state excitation have been ignored. Under steady light excitation, as mentioned above, after the heat dissipating into LO phonons, the successive heat flow to the acoustic phonons is hindered by the HPB effect between LO and acoustic phonons. Is it possible that the LO phonons’ temperature raises as a result of heat accumulation? If it is the case, the lattice should be separated into two sub-ensembles of LO phonons and acoustic phonons, each establishing a quasi-thermal equilibrium with different temperatures.

In this letter, we propose a research on the dynamics of carrier and lattice in temperature ranging from RT to cryogenic temperature. By analyzing the steady-state PLs on SiO2 encapsulated CsPbI3 QDs and CsPbI3@Cs4PbI6 complex, and key parameters extracted, we observed that a strong HPB effect in CsPbI3 QDs, in conjunction with high-density excitation, breaks the thermal equilibrium between LO and LA phonons of the lattice cryogenic temperature range, leading to anomalous behaviors on PLs at cryogenic temperatures. For CsPbI3@Cs4PbI6 complex, on the contrary, the HPB effect was largely mitigated.

The samples under investigation are perovskite QDs encapsulated in all-inorganic SiO2 particles, fabricated in a high-temperature solid-state sintering process reported in our previous work [25]. In this work, we chose two samples, the first one contains mainly CsPbI3 with a trace of Cs4PbI6 and is denoted as S-113; the second one contains mainly Cs4PbI6 with a trace of CsPbI3 and is denoted as S-113*. The detail of fabrication is introduced in Supporting information. The components of these two samples are demonstrated by the XRD data (Fig. S2 in Supporting information). The data collected for S-113 and S-113* are respectively dominated with characteristic peaks of CsPbI3 and Cs4PbI6. For S-113, there is a peak of Cs4PbI6 observed around 12°, indicating the trace of Cs4PbI6. The reason that no characteristics peaks of CsPbI3 is observed in the XRD of S-113* is ascribed to its low mole ratio that falls below the detection limit of XRD. In spite of that, the ~700-nm peaks in PL (Fig. S1 in Supporting information) reveal the existence of CsPbI3 in S-113* and definitely in S-113. Also illustrated in Fig. S1 are the PLEs and Abs., where the fingerprint 368-nm peaks in Abs. spectra of both samples indicate the existence of Cs4PbI6. Here the SiO2 shell functions as a rigid mechanical protection for the QDs inside from encroaching of water steam and oxygen. Also, the pressure exerted by the SiO2 shell on the QDs, which estimated to fall around 0.5 GPa, prevents the degradation to yellow phase [26].

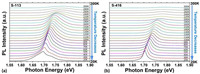

The temperature-dependent PLs of the two samples are illustrated in Fig. 1. In general, PLs of both of the samples exhibit red-shift in peak energy with shrinkage in line-width as the environmental temperature (Te) decreases. When Te becomes lower than 60 K, two shoulder peaks emerge in the PLs of CsPbI3 (Fig. S5 in Supporting information), while the PLs of Cs4PbI6 exhibit a single peak as the Te goes all the way down to 20 K. The integrated PL intensities of the two samples increases with the decreasing Te (Fig. S3 in Supporting information), although the peak intensity of S-113 decreases dramatically when multiple peaks emerge when Te goes below 50 K (Fig. S4 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Temperature-dependent PLs of (a) CsPbI3 and (b) Cs4PbI6. The Te at which each PL is captured is mark on the right. | |

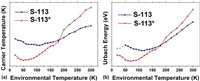

We extracted the carrier temperature (Tc) by fitting the exponential high-energy tail of these PLs (Fig. S6 in Supporting information) [9]. As shown in Fig. 2a, the plots of Tc against Te, it turns out that the Tc are much higher than Te. As Te decreases from 300 K, the Tc of two samples decreases initially, but after reach respective minima, both of them increase at low-Te range, starting from 120 K and 50 K for S-113 and S-113*, respectively.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Carrier temperature Tc and (b) Urbach energy of both samples at different environmental temperatures. | |

With the information of Tc, we also obtained the Abs. from PLs, according to the method introduced by Bhattacharya et al. [13,27]. As illustrated in Fig. S7 (Supporting information), the Abs. exhibits a slide below the band-edge, which is called the Urbach tail [18,28]. By linear fitting, we obtained the Urbach energy (EU) from the slope of the Urbach tail. which is plotted against Te in Fig. 2b. Note that due to the emergence of multi-peaks, the fitting of Abs. under Te = 50 K may not render the correct EU, thus they are plotted in grey. In Fig. 2b, it is evident that, in contrast to the previous literature which reported a monotonous correlation between EU and Te, the EU of these two sample decrease as Te goes down, after showing minimum at 110 K and 70 K for S-113 and S-113*, respectively, they increase as Te continues going downwards.

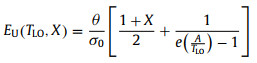

According to Cody's theory [28], the Urbach tail is a revelation of lattice disorder and can be measured by the Urbach energy EU. The lattice disorder may have multiple origins, such as Fröhlich interaction between excitons and LO phonons [6], crystalline defects [29], and halide composition [4]. The first category strongly depends on lattice temperature, which is the temperature of LO phonons (TLO); the latter two are temperature independent [30]. The EU can therefore be expressed of TLO-dependent term plus TLO-independent term as in Eq. 1.

|

(1) |

In Eq. 1, the fitting parameters of θ and σ0 being the Einstein temperature and steepness index, respectively; The θ denotes characteristic temperature in the Einstein model below which the thermal excitations of the phonons start to "freeze out". The σ0 represents an order unity [28]; the X in the first term indicates the temperature-independent contribution from defects, and the second term exhibits a monotonic increase with TLO, corresponding to the exciton-LO interaction. Therefore, could the anomalous increase in EU indicate a raise in TLO with decreasing Te? It is plausible, once one gets involved the anomalous increase in Tc and the HPB effect in TAS. As mentioned previously, the HBP effect prevent the heat transfer from HC via LO and acoustic phonons to the ambient. Under CW excitation, HCs continuously absorb energy from the laser while transferring it to LO phonons, which should successively dissipate heat to acoustic phonons. The scarce DOS between LO branch and acoustic branch create a gap that hinders heat down-transfer. On the one hand, the HPB effect causes the storage of heat in LO phonons, raising TLO, further resulting in excessively high Tc; On the other hand, as the heat flow from LO to acoustic phonon is partially blocked, the latter is cooled down by the ambient as Te decreases and the gap between acoustic and LO branches is further enlarged.

One could also note a lesser decoupling among Tc, TLO and Te in S113*. This is due to the LO-LO interaction between CsPbI3 and Cs4PbI6 on the interface [11]. The first-principle calculation indicates that the DOS of phonon of the heterojunction of CsPbI3Cs4PbI6 is far higher than that of CsPbI3 (Fig. S8 in Supporting information), which greatly mitigates the HPB effect and the decoupling among Tc, TLO and Te as well. The increase in Tc and EU cannot be a result of inefficient cooling, due to the following reasons. In Figs. 1 and 3, it is evident that the peak energy of PLs are monotonously decrease as Te goes down. If under very low temperature, e.g., Te < 50 K, the heat fails to be conducted into the ambient, the whole temperature of the sample should be elevated since the excitation laser is continuously conveying the energy. In this case, the peak energy should increase with the deceasing Te. The PL integral intensities of both samples, shown in Fig. S3 exhibit monotonous increase with decreasing temperature. If the heat dissipation fails at low Te < 50 K, it should have decreased. Such cases were never observed in our experiment. Therefore, the heat transfer from sample to ambient is always normal.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Fitting of Eq. 2 on the plots of peak energy vs. Te of S-113 and S-113*. (a) S-113* and (b) S-113 with all data involved in fitting; (c) S-113, the data captured under 50 K are excluded for fitting. The blue and dash lines illustrate the contributions of acoustic phonons and LO phonons, respectively. | |

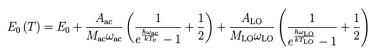

The HBP effect in CW excitation prevents the thermalization among HCs, LO phonons and acoustic phonons, which in consequence form ensembles that are no longer in thermal equilibrium with each other. Inside each ensemble, however, thermal equilibrium is established. Therefore, these ensembles have their own temperatures, which are different from other's. As the heat dissipation from lattice to ambient via interaction with acoustic phonons is always efficient, the temperature of acoustic phonons could be regarded as the same with Te. This assumption can be further verified by fitting the plot of peak energy against Te, with a modified version of the model introduced by Göbel and Saran et al. [14,17] which gives the modifications on PL peak energy from exciton-LO and exciton-acoustic phonons. We change the temperatures involved in this model into TLO and Te, specific ones corresponding to LO phonons and acoustic phonons, as shown in Eq. 2.

|

(2) |

The first term E0 in Eq. 2 is the intrinsic band-gap at 0 K. The second (red dashes, Fig. 3) is the modification via exciton-LA coupling which expands the band-gap as Te increases. The third term (blue dashes, Fig. 3) is exciton-LO coupling, which shrinks the band-gap, canceling the expansion induced by the second term as Te increases. Due to the small energy of LA phonons, at elevated temperature the condition of kT >> ħωac is always fulfilled. The second term is therefore reduced to linearity.

Firstly, we assume Te = TLO, by fitting the data of peak-energy vs. Te of both samples by Eq. 2, we obtain curves in Fig. 3a for S-113* and Fig. 3b for S-113. Both fittings go well and the parameters are listed in Table S2 (Supporting information). However, we found that these fittings yield different peak energy Ep0 at 0 K − 1.703 eV and 1.692 eV for S-113* and S-113, respectively. It is unreasonable as in these two samples the emitting centers are both CsPbI3 QDs. Noting that the PLs of S-113 feature multi-peak at Te < 50 K region, we fit the data of S-113 collected above 50 K, and yielded Ep0 = 1.702 eV, which is very close to 1.703 eV of S-113*, as illustrated by the black line in Fig. 3c. We attribute this discrepancy to the intensified HPB effect at Te < 50 K region, as has been mentioned previously. At this region from 50 K, the true TLO is larger than Te. This causes severer exciton-LO interaction that would narrow the bandgap, which is the reason that the peak energy data collected under 50 K are all lower than the theoretical prediction by those above 50 K. It also indicates the break of thermal equilibrium, or its origin, the HBP effect, only come into effect at Te < 50 K region for S-113. When Te > 50 K, one could expect a thermal equilibrium over the whole QDs. With this model in mind, the nature of the high-energy peak in PLs under 50 K of S-113 may be the anti-Stokes replica of the main peak, as the elevated TLO and Tc facilitate the phonon emission and absorption by excitons.

We note that the SiO2 shell in the sample only serves as the protections for NCs, and do not apparently play any roles in the process of excitation and recombination. However, the anomalous expansion in Urbach tail below 50 K with decreasing Te has not been observed in literature, where no rigid encapsulation with high pressure was applied. We therefore proposed that it is the pressure on the QDs that altered the lattice vibration which leads to the enhanced bottleneck effect. After all the pressure is so large that the NC appears in sphere shape rather than the normally cubic ones as it does when there is no confinement.

In summary, the HPB effect is intensified at cryogenic temperatures for CsPbI3 QDs. Its manifestations can be observed in the steady-state PL under CW excitation as anomalous expansion in both high and low energy tails, and even the emergence of multiple peaks alongside the main one, with decreasing Te. These are all ascribed to the temperature gradient over quasi-ensembles of carrier, LO phonons and acoustic phonons, induced by the HPB effect.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 62374142, 12175189 and 11904302), External Cooperation Program of Fujian (No. 2022I0004), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. 20720190005 and 20720220085), Major Science and Technology Project of Xiamen in China (No. 3502Z20191015). The authors thank Prof. Ye Yang and Dr. Zhangqiang Yang of the College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering at Xiamen University, for their supportive work and precious discussions.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109346.

| [1] |

J.Y. Kim, J.W. Lee, H.S. Jung, H. Shin, N.G. Park, Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 7867-7918. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00107 |

| [2] |

J. Yao, L. Xu, S. Wang, Z. Yang, J. Song, Nanoscale 14 (2022) 13990-14007. DOI:10.1039/d2nr03872b |

| [3] |

X. Fan, S. Wang, X. Yang, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) 2300834. DOI:10.1002/adma.202300834 |

| [4] |

M. Li, P. Huang, H. Zhong, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 14 (2023) 1592-1603. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.2c03525 |

| [5] |

S. Rudin, T.L. Reinecke, B. Segall, Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 42 (1990) 11218-11231. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.42.11218 |

| [6] |

J. Fu, Q. Xu, G. Han, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 1300. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-01360-3 |

| [7] |

Y. Yang, D.P. Ostrowski, R.M. France, et al., Nat. Photonics 10 (2015) 53-59. |

| [8] |

Z. Nie, Z. Huang, M. Zhang, et al., ACS Photonics 9 (2022) 3457-3465. DOI:10.1021/acsphotonics.2c01394 |

| [9] |

H. Shi, X. Zhang, X. Sun, X. Zhang, Appl. Phys. Lett. 116 (2020) 151902. DOI:10.1063/1.5145261 |

| [10] |

F. Sekiguchi, H. Hirori, G. Yumoto, et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 126 (2021) 077401. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.077401 |

| [11] |

Z. Nie, X. Gao, Y. Ren, et al., Nano Lett. 20 (2020) 4610-4617. DOI:10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01452 |

| [12] |

J. Yang, X. Wen, H. Xia, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 14120. DOI:10.1038/ncomms14120 |

| [13] |

J.W.M. Lim, Y. Wang, J. Fu, Q. Zhang, T.C. Sum, ACS Energy Lett. 7 (2022) 749-756. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.1c02581 |

| [14] |

T.A. Go¨bel, M. Ruf, C.T. Cardona Lin, Phys. Rev. B 57 (1998) 15183. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.57.15183 |

| [15] |

J. Lee, E.S. Koteles, M.O. Vassell, Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 33 (1986) 5512-5516. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.33.5512 |

| [16] |

J. Xu, S. Yu, X. Shang, X. Chen, Adv. Photonics Res. 4 (2022) 2200193. |

| [17] |

R. Saran, A. Heuer-Jungemann, A.G. Kanaras, R.J. Curry, Adv. Opt. Mater. (2017) 1700231. |

| [18] |

M. Ledinsky, T. Schonfeldova, J. Holovsky, et al., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10 (2019) 1368-1373. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b00138 |

| [19] |

Y. Xue, Y. Chen, G. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108447. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108447 |

| [20] |

Z. Dai, J. Chen, B. Yang, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12 (2021) 10093-10098. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c02798 |

| [21] |

Z. Bao, C.Y. Hsiu, M.H. Fang, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 34742-34751. DOI:10.1021/acsami.1c08920 |

| [22] |

M.I. Saidaminov, J. Almutlaq, S. Sarmah, et al., ACS Energy Lett. 1 (2016) 840-845. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.6b00396 |

| [23] |

J. Zhang, C. Liu, S. Wu, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 126 (2022) 8777-8786. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.2c02249 |

| [24] |

G. Kaur, K.J. Babu, N. Ghorai, et al., J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 10 (2019) 5302-5311. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.9b01552 |

| [25] |

R. Deng, X. Fan, G. Chen, et al., J. Lumin. 257 (2023) 119701. DOI:10.1016/j.jlumin.2023.119701 |

| [26] |

Y. Lin, X. Fan, X. Yang, et al., Small 17 (2021) 2103510. DOI:10.1002/smll.202103510 |

| [27] |

R. Bhattacharya, B. Pal, B. Bansal, Appl. Phys. Lett. 100 (2012) 222103. DOI:10.1063/1.4721495 |

| [28] |

G.D. Cody, T. Tiedje, B. Abeles, B. Brooks, Y. Goldstein, Phys. Rev. Lett. 47 (1981) 1480-1483. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.47.1480 |

| [29] |

C. Godet, Y. Bouizem, L. Chahed, et al., Phys. Rev. B: Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 44 (1991) 5506-5509. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.44.5506 |

| [30] |

M. Letz, A. Gottwald, M. Richter, L. Parthier, Phys. Rev. B 79 (2009) 195112. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.79.195112 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35