b State Key Laboratory of Chemical Resource Engineering, Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Soft Matter Science and Engineering, College of Chemistry, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing 100029, China

Nowadays, lithium-ion batteries have become an indispensable part of portable energy storage devices and are widely used in consumer electronics and electric vehicles [1,2]. However, the existing commercial lithium ion batteries are based on organic liquid electrolyte with an inflammable solvent. Organic liquid electrolytes have high ionic conductivity and good electrode/electrolyte interface wetting but also have low mobility coefficient of lithium ions, flammability, easy leakage and poor safety [3,4]. In particular, the unstable Li metal deposition and dendrite growth in traditional liquid electrolytes will cause a series of safety problems and hinder the further development of lithium metal batteries [5,6]. Compared with liquid electrolyte, the high mechanical strength and non-flammability of solid electrolyte can not only solve the problem of lithium battery safety but also make the all-solid lithium metal battery with higher energy density by matching lithium metal anode with high voltage cathode, which attracts the attention of researchers all over the world [7–12].

Solid electrolytes mainly consist of inorganic solid electrolytes and organic solid electrolytes, both of which have high safety and thermal stability [13,14]. They are ideal substitutes for widely used flammable liquid electrolytes. Compared with inorganic solid electrolytes (oxides, sulfides, fast ionic conductors), solid polymer electrolytes are characterized by good interface compatibility, plasticity, and easy membrane formation [15–19]. At present, polyethylene oxide (PEO) is one of the most widely used organic solid Li+ conduction conductor, featuring with low cost, high dielectric constant, strong processability and other excellent characteristics [20–27]. However, PEO is a semi-crystalline polymer, which usually needs to work at a temperature higher than the melting point of PEO to eliminate crystallization [28]. However, high temperature not only increases the chain movement and ionic conductivity of PEO but also inevitably decreases the mechanical strength of PEO as a solid electrolyte and increases the risk of short circuit in battery [11,29–35]. In addition, maintaining high temperature also reduces the energy efficiency of the battery system. Therefore, increasing the room temperature conductivity of polymer electrolytes while maintaining sufficient mechanical strength is critical for the development of polymer solid state batteries [10,21,36,37]. Since Li+ transport in polymers is achieved through segment movement in amorphous regions, increasing the amorphous phase content can effectively increase the Li+ ionic conductivity in solid polymer electrolyte. Polymers formed from different monomers copolymerization can reduce the crystallinity of the polymer, improve the movement ability of the chain end and take advantage of different functional blocks, thus enhancing the performance of the polymer electrolyte [13,38–40]. However, PEO in traditional block copolymers usually needs a high molecular weight to ensure the phase separation structure, which leads to problems such as low kinetic ability, high melting point, low electrical conductivity and poor mechanical toughness. Till now, it still remains a challenge to obtain solid polymer electrolytes with high room temperature ionic conductivity and excellent mechanical properties [41–43].

In this paper, a series of solid polymer electrolytes with different nano phase separation structures were obtained by using alternate copolymer styrene-maleic anhydride as the backbone to construct grafted block copolymers, which achieved high room temperature ion transport (10−4 S/cm) and notable mechanical properties (1.4 MPa) at the same time. In which, the PEO chain is used as the soft building block to provide high ionic conductivity and SMA copolymer as hard building block to provide high mechanic strength [44]. It also has remarkable chemical and mechanical stability toward lithium metal anode, showing no short circuit of Li||Li symmetric cell cycling at 0.1 mA/cm2 for more than 1500 h. Full cells of Li||LiFePO4 can work efficiently and stably at room temperature, delivering a high capacity of 151 mAh/g and remaining 85.6% capacity retention after 400 cycles at 25 ℃ and 0.2 C/0.2 C charge/discharge conditions. More importantly, the nano phase separated polymer solid electrolyte can greatly improve safety performance of Li||LiFePO4 pouch cells under all kinds of abuse conditions without catching fire or smoking, showing great potential for practical applications.

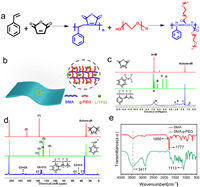

Fig. 1a showed the chemical precursors and synthesis of the grafted alternate copolymer, including an alternate copolymer SMA as backbone, and soft PEO chains as side chains. Aromatic groups present in SMA provide rigidity, while PEG chains provide flexibility in Li-ion transport. The grafted alternate copolymer takes advantage of these building blocks and can provide high Li+ conductivity at room temperature while maintaining notable mechanical strength, as depicted in Fig. 1b. The SMA was synthesized from styrene (St) and maleic anhydride (MA) by precipitation polymerization [45]. The copolymerization of styrene and maleic anhydride is a typical alternating copolymerization [46]. Maleic anhydride monomers and styrene monomers are arranged alternately in a strict 1:1 ratio to form alternating copolymers. Deuterated acetone as solvent, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of St, MA, SMA block copolymer were shown in Figs. 1c and d. According to the 1H spectrum, 3.1–3.8 ppm (3, 4), 6.5–7.8 ppm (A) and 1.25–2.5 ppm (1, 2) correspond to the methine groups of maleic anhydride, benzene ring and methylene in styrene, respectively, which can be tentatively determined for the synthesis of SMA. The chemical shifts at 173 ppm (C5+C6), 126–130 ppm (C8-C12), and 137–138 ppm (C7) in Fig. 1d correspond to the characteristic peaks of carbonyl carbon, tertiary carbon on benzene ring, and quaternary carbon on benzene ring in maleic anhydride, respectively. Through the specific chemical shift of the quaternary carbon in the benzene ring, we can determine that the synthesized product is a styrene-maleic anhydride alternating copolymer. The gel chromatography (GPC) test was performed to measure the molecular weights and corresponding polydispersity indices (PDI) of SMA. The molecular weight of SMA is estimated to be Mn =13, 997 g/mol and PDI is 1.739 (Fig. S1 in Supporting information), indicating the monodisperse nature of the synthesized SMA. Next, a series of SMA-g-PEG copolymers (denoted as SMA-g-PEGx, in which x denotes the molecular weight of PEG) have been synthesized by ring opening polymerization. Fig. 1e shows the FT-IR spectra of SMA and SMA-g-PEGx block copolymers [47]. It can be seen from the spectra that SMA had two main functional groups (-C=O and -C-O) and their stretching vibration peaks were observed at 1856 cm−1 and 1777 cm−1, respectively. After introducing PEG on to the backbone, the intensity of the band associated with the -C-O and -OH groups were detected at 1777, 1113, and 3417 cm−1 for SMA-g-PEGx copolymers [48]. These spectral feature changes prove successful graft modification of SMA and formation of SMA-g-PEGx.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Synthesis scheme for the nanophase separated, grafted alternate copolymer electrolyte. (a) Main chemicals and synthesis steps of copolymers SMA-g-PEG. (b) Schematic illustration of SPE, in which SMA main chains as backbone provide rigidity while the grafted PEG short chains provide flexibility for Li-ion transport. Thus the membrane has balanced mechanic strength and ionic conductivity. (c) 1H and (d) 13C NMR spectra comparison of styrene, maleic anhydride and SMA. (e) FTIR spectra of SMA and SMA-g-PEG. | |

Free-standing films can be formed due to the mechanical properties of the synthesized electrolytes. Therefore, a series of white flexible polymer films were formed by a solution-casting method. As illustrated in Fig. S2 (Supporting information), when the molecular weight of PEG is 400, the polymer electrolyte membrane is brittle and easy to crack (Fig. S2a). As the molecular weight of PEG increases, the polymer electrolyte membrane becomes homogeneous and tough (Figs. S2b and c). Among them, the surface of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE polymer film is smooth and more flexible, indicating a good contact with the electrode. Furthermore, the SEM characterization revealed that the surface (Fig. S3 in Supporting information) of the SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE membrane was smooth and dense. When the molecular weight of PEG is 2000, the polymer electrolyte has the highest ionic conductivity at room temperature (Fig. S4 in Supporting information). Thus, this is chosen as our formula for the polymer electrolyte films, denoted as SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE.

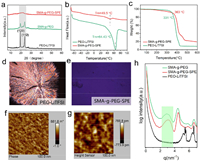

PEO is a crystalline polymer which is brittle and has low Li+ conductivity at room temperature. Block copolymerization can diminish the regularity of PEO chain segments while maintaining good flexibility, inhibiting crystallization, reducing the glass transition temperature and enhancing polymer molecular motility [30,49–52]. The crystallinity of SMA-g-PEG2000 and PEO based electrolyte was detected by X-ray diffraction (XRD) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). As shown in Fig. 2a, the XRD pattern of pure PEO-LiTFSI exhibits typical Bragg reflections at 2θ degree of 19.08° and 23°, which can be assigned to (120) and (112) diffraction of highly crystalline PEO due to ordered arrangement of the polyether chains. PEG2000-LiTFSI shows XRD pattern similar with PEO-LiTFSI (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). The peaks of SMA-g-PEG2000 were almost identical to those of PEO-LiTFSI, indicating that the ordered structure of PEG chains remained unchanged. However, after adding lithium salt of LiTFSI, the SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE revealed a broad diffraction peak at ≈20°, indicating its amorphous nature. In solid state polymer electrolytes, the Li+ transport is mainly dependent on the chain segment movement in the amorphous region of the polymer, so we believe that the Li-ion transport will be improved in SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE. Fig. 2b demonstrates the DSC curves of PEO-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE. A relatively sharp endothermic peak is observed at 64.43 ℃, indicating the melting temperature (Tm) of PEO-LiTFSI [26]. With the modification of PEG2000 to obtain grafted block copolymers, the endothermic peak for the Tm of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE is shifted to a lower temperature of 49.5 ℃. The lower Tm of the rafted copolymer electrolyte implies a decrease in the degree of crystallinity compared to that of PEO-LiTFSI, which is in good agreement with XRD results. We should note that the reduction in crystallinity facilitates the proportion of amorphous regions and thus improves the ionic conductivity. To ensure a safe and workable battery, solid polymer electrolytes must have high thermal stability, which were further analyzed by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Fig. 2c). The SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE becomes unstable at around 363 ℃, higher than that PEO-LiTFSI (331 ℃), which is beneficial to the safety of solid-state batteries. High mechanic strength is also a key need for polymer electrolyte. The tensile stress–strain curve of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE was shown in Fig. S6 (Supporting information). The SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE membrane's tensile stress was determined to be 1.45 MPa. This is due to the fact that SMA copolymer is a strong building block as the backbone of SPE membrane, endowing the overall mechanical strength of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Physical characterization of crystalline PEO-LiTFSI and nano phase separated copolymer SMA-g-PEG-SPE, in which the molecule weight of the grafted PEG is 2000. (a) XRD patterns of PEO-LiTFSI, SMA-g-PEG, and SMA-g-PEG-SPE. (b) DSC and (c) TGA profiles of SMA-g-PEG-SPE and PEO-LiTFSI. POM images of (d) PEG and (e) SMA-g-PEG at 25 ℃. Before taking pictures, the samples were heated to 150 ℃, then cooled down to 25 ℃ at a cooling rate of 10 ℃/min. (f, g) AFM characterization of SMA-g-PEG-SPE membrane (phase and high sensor photos). (h) SAXS characterization of PEO-LiTFSI, SMA-g-PEG, and SMA-g-PEG-SPE. | |

Besides, the polymer crystal morphology of PEO-LiTFSI, PEG2000-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE was investigated by polarizing microscope (POM). Figs. 2d and e show the POM pictures of PEG-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE. As can be seen from the POM (Fig. 2d), PEG-LiTFSI shows clear cross-extinction phenomenon, a spherulite crystal structure at room temperature with large crystalline size [53]. For PEO-LiTFSI, dense spherical crystals appeared after isothermal crystallization with much smaller crystalline size (Fig. S7 in Supporting information). In contrast, the spherulite crystals have vanished for SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE, and the visual field of POM is black (Fig. 2e), which is consistent with the XRD result that SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE is largely amorphous. Due to the breakdown of the copolymer crystal structure, the crystallization of PEG chains in SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE is limited, thus making the grafted PEG chains to be an amorphous phase.

Thin films of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE were prepared by spin-casting from DMAC solutions and characterized by atomic force microscope (AFM) [54,55]. In Figs. 2f and g, the dark areas in the image represent soft segments and the bright areas represent hard segments. The phases of soft and hard segments are distributed alternately, presenting distinct nano phase separation. Thereafter, SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE and PEO-LiTFSI were analyzed by small angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) at room temperature. As shown in Fig. 2h, SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE showed a broad peak at around q = 2.9 nm−1, which further confirmed the nano phase separation [56,57]. The presence of the nano phase separation structure promotes lithium ion transport by limiting the crystallization of PEG and thus increasing the area of the amorphous region on the one hand, while on the other hand the block structure provides the mechanical properties to would be extremely beneficial in suppressing lithium dendritic growth.

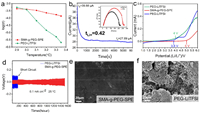

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was used to investigate the ionic conductivity of these SPEs at different temperatures (from 25 ℃ to 70 ℃) (Fig. S8 in Supporting information), Arrhenius plots of ionic conductivity for PEO-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE were illustrated in Fig. 3a. At 25 ℃, SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE has an ionic conductivity of 1.14 × 10−4 S/cm, which is several orders of magnitude higher than that of PEO-LiTFSI (2.07 × 10−6 S/cm). The increase of amorphous area in the polymer electrolyte should be the reason for the increase of ionic conductivity. For comparison, we also made solid state polymer electrolyte of PEG-LiTFSI. The PEG-LiTFSI membrane was prepared by a simple melt-infusion process in which the melted PEG2000 and LiTFSI is impregnated together into a porous TF 4030 separator at a temperature of 120 ℃. PEG-LiTFSI is not stable at high temperature and ionic conductivity at 25 ℃ is 8.02 × 10−7 S/cm (Fig. S9 in Supporting information). Lithium ion mobility, in addition to ionic conductivity, is another significant parameter for polymer electrolyte application. Increasing the Li+ mobility can reduce concentration polarization during the charging/discharging process, thus mitigating overpotential of the battery. The transference number of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE was measured through alternating current (AC) impedance and direct current (DC) polarization using a Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|Li symmetrical cell. In Fig. 3b, the calculated transference number of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE is 0.42 at 25 ℃, which is higher than the commonly reported 0.21 of PEO-LiTFSI (Fig. S10 in Supporting information). Fig. 3c depicts the electrochemical windows of the polymer electrolyte. In the anodic process, the SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE shows high voltage stability until 5.0 V, but PEG-LiTFSI and PEO-LiTFSI are decomposed at 3.8 V and 4.0 V respectively. The stability of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE is attributed to the rigid support role of the benzene ring in its block polymer structure and more stable interfacial compatibility.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Electrochemical performance of SMA-g-PEG-SPE membrane. (a) The ionic conductivity of PEO-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG-SPE in the temperature range from 25 ℃ to 70 ℃. (b) Time-dependent current curve with a potentiation polarization of 10 mV at 25 ℃ for Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|Li symmetrical cell. Inset: Nyquist plot of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|Li symmetrical cell before and after polarization. (c) Linear sweep voltammetry of PEO-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE. (d) Voltage vs. cycle time profiles of Li|PEO-LiTFSI|Li and Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|Li symmetric cells at current density of 0.1 mA/cm2. SEM images of the cycled Li anodes from cells using (e) SMA-g-PEG-SPE and (f) PEO-LiTFSI as separators. | |

Li||Li symmetric cells were used to test the stability of Li metal anode with different SPEs. The Li||Li symmetrical cells using PEO-LiTFSI could not work at room temperature due to its low ionic conductivity and poor interface contact with Li metal at room temperature (Fig. S11 in Supporting information). For PEG-LiTFSI, the cell showed overpotential of 200 mV and short circuit after 205 cycles, which is caused by the low ionic conductivity and unstable electrolyte/Li interface with continuous side reaction. In striking contrast, the Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|Li cell showed stable lithium plating/stripping with overpotential less than 100 mV at the current density of 0.1 mA/cm2 over 1500 h, as illustrated in Fig. 3d, indicating that SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE maintained good interfacial compatibility and mechanical stability. The morphology of Li metal anodes after cycling was examined by SEM. As shown in Fig. 3e, it can be seen that the surface of the cycled Li metal from Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|Li cell is smooth with no cracks or puncture structures. However, uneven Li growth and cracks were observed on the cycled Li metal from PEG-LiTFSI based Li||Li symetrical cell, and the uncontrolled Li dendrite growth and side reaction caused cell failure (Fig. 3f). Based on the collective experimental evidence, we can conclude that SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE, with its high ionic conductivity, facilitates Li+ ion transport. Additionally, its strong mechanic strength aids in the suppression of Li metal dendrites growth, thereby contributing to the stable cycling of Li metal cells.

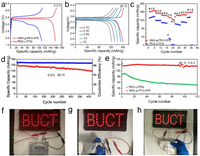

In order to evaluate the application potential of our solid polymer electrolyte, Li||LFP full cells were assembled. Li||LFP using PEO-LiTFSI membrane cannot work at room temperature, therefore, we only compared Li||LFP full cells using PEG2000-LiTFSI and SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE as electrolytes at 25 ℃. However, we compared Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP and Li|PEO-LiTFSI|LFP at 60 ℃, due to the fact that PEG2000-LiTFSI was not stable at elevated temperature and PEO-LiTFSI was the benchmark of solid polymer electrolyte. Fig. 4a shows the initial charge and discharge curves of Li metal cells at 25 ℃ and 0.2 C/0.2 C rates. It can be seen that Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|LFP delivers a high discharge capacity of 158 mAh/g, while that of Li|PEG-LiTFSI|LFP is only 110 mAh/g. Besides, Li metal cells with SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE show flat charge/discharge plateau and lower polarization when compared to PEG-LiTFSI based Li metal cells. In Fig. 4b, we can see that Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|LFP exhibited two well-defined potential plateaus and high capacity at different C rates from 0.1 C to 2.0 C, corresponding to the stable de-lithiation and lithiation processes. Fig. 4c shows the rate capability of different solid state Li metal cells. The reversible capacities of Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|LFP are 162.3, 156, 145.1, 138.4 and 127.9 mAh/g at 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 C. However, capacities of PEG-LiTFSI based cell are 131, 119, 108.7, 49.3 and 1.6 mAh/g at 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 C. Fig. 4d demonstrates the cycling performance of Li|SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE|LFP, which shows an initial capacity of 151 mAh/g and excellent stability with capacity retention of 85.6% after 400 cycles at 0.2 C and 25 ℃. As shown in Fig. S12 (Supporting information), we compared the performance of recently reported solid-state electrolytes. It is observed that SMA-g-PEG-SPE exhibits superior ionic conductivity and cycle stability, outperforming the other materials in the comparison. Subsequently, the cycle performance of Li||LiFePO4 at high temperature (60 ℃) was investigated. For SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE, the highest discharge capacity of Li metal full cell is 152.3 mAh/g at 0.5 C, which maintains 145.2 mAh/g over 120 cycles (Fig. 4e). On the contrary, the discharge capacity of PEO-LiTFSI-based Li metal full cell drops quickly to only 50 mAh/g after 100 cycles, showing poor cycle stability with capacity retention of 30.2% at the same condition. The excellent electrochemical performance of SMA-g-PEG2000-SPE based Li metal full cells is ascribed to the high ionic conductivity and sufficient mechanical strength of the polymer electrolyte used. In order to evaluate the feasibility for commercial application of this nano phase separated, PEG grafted polymer electrolyte, Li||LFP pouch cells were fabricated and fully charged to power an illuminous sign that composed of 49 LED bulbs (Fig. 4f). The safety of Li||LFP pouch cell is demonstrated at room temperature under destructive conditions in Figs. 4g and h. Even the Li||LFP pouch cell bended to different angles, it can still light the illuminous sign without any liquid leakage, fire or smoking. The outstanding flexibility and reliability of our polymer electrolyte can expand the application of Li metal batteries to areas such as flexible and deformable energy devices.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Electrochemical performance of Li||LFP full cells. (a) Charge and discharge curves of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP and Li|PEG-LiTFSI|LFP at 0.2 C rate and 25 ℃. (b) Charge and discharge curves of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP at different C-rates and 25 ℃. (c) Rate capability of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP and Li|PEG-LiTFSI|LFP at different C-rates. (d) Long term cycling performance of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP at 0.2 C rate and 25 ℃. (e) Cycle performance of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP and Li|PEO-LiTFSI|LFP at 0.5 C rate and 60 ℃. (f-h) Optical photograph of Li|SMA-g-PEG-SPE|LFP pouch cell working in abuse conditions, which still lights up the LED illuminous sign. | |

In this work, solid polymer electrolytes with nano phase separation structure was synthesized by using the lithium ion conductive polyethylene glycol chain as functional group and the poly phenene-maleic anhydride as hard backbone to provide Li+ conductivity and mechanical strength. It was found that polyethylene glycol with appropriate molecule weight (mW of 2000) grafted on the alternate block copolymer of styrene-maleic anhydride had excellent mechanical strength (1.4 Mpa), high ionic conductivity (1.14 × 10−4 S/cm) and wide electrochemical window (5.0 V). As a result, the polymer electrolyte enabled Li||LiFePO4 full cell with a high discharge capacity of 151 mAh/g at 25 ℃ and 0.2 C/0.2 C charge/discharge rate, which still remained 85.6% after 400 cycles. In addition, the Li||LiFePO4 pouch cell showed excellent safety performance under a variety of abuse conditions. This work provided a high performance solid polymer electrolyte which had great potential for practical application in lithium metal batteries.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21771018, 21875004, 22108149), Beijing University of Chemical Technology (No. buctrc201901), Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation-Xiaomi Innovation Joint Fund (No. L223011). In addition, the work was also supported by the program "Research on key technologies of solid-state batteries-research and development of organic−inorganic composite solid-state electrolytes" from China Three Gorges Corporation (No. 202103036)

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108887.

| [1] |

S. Xia, X. Wu, Z. Zhang, Y. Cui, W. Liu, Chem 5 (2019) 753-785. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.11.013 |

| [2] |

X. Yang, J. Luo, X. Sun, Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (2020) 2140-2195. DOI:10.1039/c9cs00635d |

| [3] |

L. Xu, S. Tang, Y. Cheng, et al., Joule 2 (2018) 1991-2015. DOI:10.1016/j.joule.2018.07.009 |

| [4] |

D. Zhang, L. Li, W. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107122. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.01.015 |

| [5] |

Y. Wang, L. Ren, J. Liu, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 50982-50991. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c15662 |

| [6] |

L. Ren, X. Cao, Y. Wang, et al., J. Alloys Compd. 947 (2023) 169362. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169362 |

| [7] |

X.B. Cheng, C.Z. Zhao, Y.X. Yao, et al., Chem 5 (2019) 74-96. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.12.002 |

| [8] |

Z. Wang, L. Shen, S. Deng, P. Cui, X. Yao, Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2100353. DOI:10.1002/adma.202100353 |

| [9] |

F. Xu, S. Deng, Q. Guo, D. Zhou, X. Yao, Small Methods 5 (2021) 2100262. DOI:10.1002/smtd.202100262 |

| [10] |

D.G. Mackanic, X. Yan, Q. Zhang, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 5384. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13362-4 |

| [11] |

Z. Wang, Q. Guo, R. Jiang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 435 (2022) 135106. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2022.135106 |

| [12] |

S. Zhang, B. Cheng, Y. Fang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3951-3954. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.11.024 |

| [13] |

J. Lopez, D.G. Mackanic, Y. Cui, Z. Bao, Nat. Rev. Mater. 4 (2019) 312-330. DOI:10.1038/s41578-019-0103-6 |

| [14] |

L. Liu, Z. Wu, Z. Zheng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4326-4330. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.12.031 |

| [15] |

K. Liang, H. Zhao, J. Li, et al., Small 19 (2023) 2207562. DOI:10.1002/smll.202207562 |

| [16] |

H. Wang, L. Sheng, G. Yasin, et al., Energy Storage Mater 33 (2020) 188-215. DOI:10.3390/microorganisms8020188 |

| [17] |

L. Ren, J. Liu, Y. Zhao, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 33 (2023) 2210509. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202210509 |

| [18] |

M. Ge, X. Zhou, Y. Qin, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3894-3898. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.11.073 |

| [19] |

L. Ren, Q. Wang, Y. Li, et al., Inorg. Chem. Front. 8 (2021) 3066-3076. DOI:10.1039/d1qi00205h |

| [20] |

J. Atik, D. Diddens, J.H. Thienenkamp, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 11919-11927. DOI:10.1002/anie.202016716 |

| [21] |

X. Cai, J. Ding, Z. Chi, et al., ACS Nano 15 (2021) 20489-20503. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.1c09023 |

| [22] |

H. Zhao, J. Zhong, Y. Qi, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 465 (2023) 143032. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.143032 |

| [23] |

L. Han, C. Liao, X. Mu, et al., Nano Lett. 21 (2021) 4447-4453. DOI:10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c01137 |

| [24] |

S.H. Lee, J.Y. Hwang, J. Ming, et al., ACS Energy Lett. 6 (2021) 2153-2161. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00661 |

| [25] |

H. Zhao, Y. Qi, K. Liang, et al., Rare Met. 41 (2022) 1284-1293. DOI:10.1007/s12598-021-01864-4 |

| [26] |

Y.L. Ni'mah, M.Y. Cheng, J.H. Cheng, J. Rick, B.J. Hwang, J. Power Sources 278 (2015) 375-381. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.11.047 |

| [27] |

J. Tan, X. Ao, A. Dai, et al., Energy Storage Mater. 33 (2020) 173-180. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2020.08.009 |

| [28] |

H.M. Ye, L.T. Hong, Y. Gao, J. Xu, Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 888-892. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.12.032 |

| [29] |

Z. Wei, Z. Zhang, S. Chen, et al., Energy Storage Mater. 22 (2019) 337-345. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2019.02.004 |

| [30] |

H. Xu, A. Wang, X. Liu, et al., Polymer 146 (2018) 249-255. DOI:10.1016/j.polymer.2018.05.045 |

| [31] |

S. Xu, Z. Sun, C. Sun, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 30 (2020) 2007172. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202007172 |

| [32] |

M. Yao, Q. Ruan, T. Yu, H. Zhang, S. Zhang, Energy Storage Mater. 44 (2022) 93-103. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2021.10.009 |

| [33] |

B. Yuan, B. Zhao, Q. Wang, et al., Energy Storage Mater 47 (2022) 288-296. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2022.01.052 |

| [34] |

J. Zheng, C. Sun, Z. Wang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 18448-18453. DOI:10.1002/anie.202104183 |

| [35] |

Z. Xie, Y. Zhou, C. Ling, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1407-1411. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.031 |

| [36] |

Z. Huang, S. Choudhury, N. Paul, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 12 (2021) 2103187. |

| [37] |

H. Wang, Q. Wang, X. Cao, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) e2001259. DOI:10.1002/adma.202001259 |

| [38] |

V. Bocharova, A.P. Sokolov, Macromolecules 53 (2020) 4141-4157. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02742 |

| [39] |

V. Vijayakumar, B. Anothumakkool, S. Kurungot, M. Winter, J.R. Nair, Energy Environ. Sci. 14 (2021) 2708-2788. DOI:10.1039/d0ee03527k |

| [40] |

Q. Zhou, J. Ma, S. Dong, X. Li, G. Cui, Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) e1902029. DOI:10.1002/adma.201902029 |

| [41] |

W. Guo, W. Zhang, Y. Si, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 3031. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-23155-3 |

| [42] |

K. Kato, K. Inoue, M. Kudo, K. Ito, Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 10 (2014) 2573-2579. DOI:10.3762/bjoc.10.269 |

| [43] |

Y.C. Lin, K. Ito, H. Yokoyama, Polymer 136 (2018) 121-127. DOI:10.1016/j.polymer.2017.12.046 |

| [44] |

B. Tang, Q. Zhou, X. Du, et al., Nano Select 1 (2020) 59-78. DOI:10.1002/nano.202000009 |

| [45] |

S.M. Lee, W.L. Yeh, C.C. Wang, C.Y. Chen, Electrochim. Acta 49 (2004) 2667-2673. DOI:10.1016/j.electacta.2004.02.018 |

| [46] |

B.T. Tang, Z. Yang, S.F. Zhang, Adv. Mater. Res. 557–559 (2012) 1192-1196. |

| [47] |

H. Qian, Y.X. Zhang, S.M. Huang, Z.Y. Lin, Appl. Surf. Sci. 253 (2007) 4659-4667. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2006.10.017 |

| [48] |

X. Yang, M. Jiang, X. Gao, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 13 (2020) 1318-1325. DOI:10.1039/d0ee00342e |

| [49] |

S. Imai, Y. Ommura, Y. Watanabe, et al., Polym. Chem. 12 (2021) 1439-1447. DOI:10.1039/d0py01505a |

| [50] |

S. Bhaumik, K. Ntetsikas, N. Hadjichristidis, Macromolecules 53 (2020) 6682-6689. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02326 |

| [51] |

Y. Lee, M.P. Aplan, Z.D. Seibers, et al., Macromolecules 51 (2018) 8844-8852. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01859 |

| [52] |

M. Liu, Y. Jiang, D. Liu, et al., ACS Energy Lett. 6 (2021) 3228-3235. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.1c01482 |

| [53] |

A. Sarı, A. Biçer, C. Alkan, Int. J. Energy Res. 44 (2020) 3976-3989. DOI:10.1002/er.5208 |

| [54] |

T. Rejek, P. Schweizer, D. Joch, et al., Macromolecules 53 (2020) 5604-5613. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.9b02760 |

| [55] |

Z. Liu, Q. Hu, S. Guo, L. Yu, X. Hu, Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) e2008088. DOI:10.1002/adma.202008088 |

| [56] |

T. Li, A.J. Senesi, B. Lee, Chem. Rev. 116 (2016) 11128-11180. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00690 |

| [57] |

F. Wang, C. Li, J. Sang, Y. Cui, H. Zhu, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 46 (2021) 36301-36313. DOI:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2021.08.172 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35