b School of Applied Chemistry and Engineering, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China;

c Department of Chemistry, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084, China

Cross-coupling reactions have become a crucial tool in pharmaceutical and fine chemical production because it is one of the most effective means to construct C—C bond, such as Suzuki cross-coupling and Heck cross-coupling reactions [1–9]. Palladium-based catalysts are regarded as the most outstanding catalysts for cross-coupling reactions and have attracted extensive attention. Palladium-based homogeneous catalysts initially used in the cross-coupling reactions gradually faded from current research concerns due to the shortcomings of recovery, product purification, and environmental hazards of toxic ligands [10–13]. As a result, palladium-based heterogeneous catalysts promptly became the forefront of research because of the remarkable advantages of recovery and separation. Relative to the low abundance of palladium, improving the dispersion and utilization rate of palladium is a crucial issue for the design of palladium-based heterogeneous catalysts. Obviously, due to the limitation of Pd species size, supported heterogeneous catalysts which dispersed palladium nanoparticles or clusters by a high-surface area solid support suffer from poor reactivity, inferior atomic economy, and poor application prospect [14–19]. On this basis, single-atom catalysts (SACs) that maximize Pd atom utilization by isolating Pd single atoms on a support surface are considered promising to solve these disadvantages [20–25]. Chen et al. revealed that Pd-ECN has excellent reactivity in Suzuki coupling reaction by isolating Pd atoms on the ECN support [22]. Although there has been some success, due to the interaction between the Pd atoms and the support, Pd atoms in SACs exhibit positive electrical properties and reduced electron density, which degrades the reactivity to a certain extent in cross-coupling reaction compared with electron-rich Pd active center [26,27]. For this reason, it is significant for cross-coupling reaction to construct a new catalyst with the advantages of high atom utilization and stable electron-rich Pd active sites.

Coincidentally, the structural features of single-atom alloys (SAAs) satisfy the above requirements [28–30]. The basic SAAs can be described as the isolated noble metal atoms that are stabilized on the surface of another metal through new metallic bonds. Thus SAAs also have the advantage of 100 percent atom utilization [31–33]. Besides, due to the electron transfer between noble metal atoms and support metal atoms, the noble metal atoms of SAAs have the electronic state of the free metal atom and rich electron density [34–37]. In short, the extremely high atomic utilization and rich surface electron density of noble metals allow SAAs to acquire very high cross-coupling reactivity with very low Pd content in theory. Besides, the practical potential of SAAs in constructing C—C bonds has also been demonstrated by Pd/Au SAA, which has great reactivity and recovery ability in the Ullmann reaction [38]. Although theoretical and practical feasibility is clear, no SAAs are being used for cross-coupling reaction, which is an urgent problem to be solved.

Herein, we successfully construct a PdNi single-atom alloy by a galvanic replacement reaction between the H2PdCl4 precursor and the Ni NPs obtained by the high-temperature reduction of Ni-Al layered double hydroxides (LDHs). A battery of elaborate characterizations, including AC-HAADF-STEM, CO-DRIFTS, and XPS, verify the formation of PdNi SAA structure, in which Pd atoms are isolated by Ni atoms on the surface of Ni NPs. The 0.1% PdNi SAA exhibits extraordinary catalytic performance toward the Suzuki coupling reaction between 4-bromoanisole and phenylboronic acid (yield 96.6%, selectivity 97%) at 80℃ for 1 h. Noteworthily, the reaction rate of 0.1% PdNi SAA is much higher than Pd/Al2O3 catalyst (4.7-fold) and other bimetallic PdNi samples with higher Pd content (13.1, 82.7-fold). In addition, 0.1% PdNi SAA also showed good reactivity in Heck coupling reaction. As mentioned above, the unique zero-valent Pd atoms with rich electrons and 100 percent atom utilization efficiency of PdNi SAA determine its excellent catalytic performance.

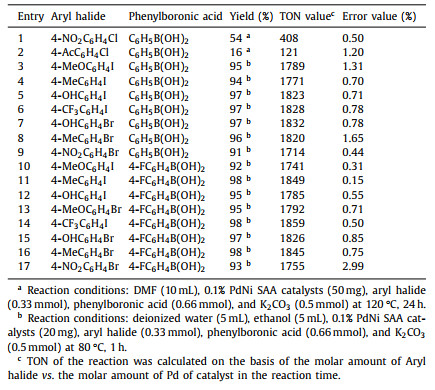

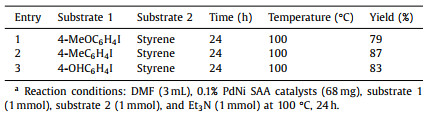

The entire synthesis route of PdNi bimetallic catalysts is illustrated in Fig. 1a. Firstly, the substrate of Ni nanoparticles (NPs) highly dispersed on amorphous alumina was obtained by high-temperature reduction of Ni-Al LDHs. Subsequently, three PdNi bimetallic catalysts with different Pd contents (0.1 wt%, 0.8 wt%, 3 wt%) were prepared by a simple galvanic replacement (GR) method to disperse Pd atoms on the surface of Ni NPs. The accurate element contents of three bimetallic catalysts are determined by inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES, Table S1 in Supporting information). The Pd contents of 0.1% PdNi, 0.8% PdNi, and 3% PdNi are 0.093 wt%, 0.807 wt%, and 3.056 wt%, respectively. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Figs. S1-S4 in Supporting information) reveal that Ni NPs of Ni substrate and three PdNi samples are anchored and highly dispersed onto the Al2O3 support with a close size (16.5–20.2 nm), and there are no obvious changes of the PdNi bimetallic catalysts morphology structure during the GR process. High-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM, Fig. 1b) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM, Fig. S1c) demonstrated that both Ni substrate and PdNi samples exhibit a uniform lattice spacing of ~0.203 nm indexed to Ni (111) and the lattice fringes of Pd species are absent. The XRD patterns (Fig. 2a and Fig. S5 in Supporting information) of both 0.1% PdNi and 0.8% PdNi samples show a series of the same characteristic reflections like substrate at 2θ 44.5°, 51.8°, and 76.3°, corresponding to the (111), (200), and (220) of a Ni (JCPDS No. 04-0850) phase. The absence of characteristic reflections of metallic or oxidic Pd phase implies a high dispersion of Pd species. Differently, due to high Pd contents, the XRD patterns (Fig. S5) of the 3% PdNi sample show obvious characteristic reflections at 2θ 40.0°, 46.5°, and 67.9°, indexed to the (111), (200), and (220) of a Pd (JCPDS No. 88-2335) phase, which demonstrated the existence of Pd clusters or NPs. Meanwhile, the 0.15% Pd/Al2O3 control sample was synthesized by a simple impregnation method, in which Pd atoms were highly dispersed on the surface of amorphous Al2O3 (Fig. S7 in Supporting information).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Synthesis process and morphological characterizations of 0.1% PdNi SAA. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis approach of bimetallic PdNi samples. (b, c) AC-HAADF-STEM images of 0.1% PdNi SAA. The crystal plane spacing of 0.203 nm indexed to the (111) plane of the metallic Ni. (d) The enlarged area labeled by the white dashed line of (c). (e) enlarged STEM image and (f) corresponding intensity profile of 0.1% PdNi SAA. (g) EDS mapping images of 0.1% PdNi SAA. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Characterizations of catalyst structure. (a) XRD patterns of NiAl-LDH, Ni/Al2O3, and 0.1% PdNi SAA. (b) CO-DRIFTS spectra of 0.1% PdNi SAA, 0.8% PdNi, and 3% PdNi samples, within 2120–1800 cm−1 by flowing He gas for 20 min. (c) The enlarged and peak fitting curves of (b) within 2120–2010 cm−1. (d) Pd 3d XPS spectra of 0.1% PdNi SAA, 0.8% PdNi, and 3% PdNi samples. | |

Aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (AC-HAADF-STEM) was carried out to provide a more unambiguous surface distribution state of Pd and Ni species in 0.1% PdNi sample. It is obvious in AC-HAADF-STEM images (Figs. 1c and d) to distinguish numerous atom-sized brighter spots (highlighted by white cycles) on the surface of Ni NPs attributed to individual Pd atoms without any Pd clusters or NPs information. And the enlarged AC-HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 1e) and the intensity profile (Fig. 1f) further confirm that isolated Pd atoms are highly dispersed on the surface of Ni NPs, demonstrating the successful synthesis of PdNi single-atom alloy structure. Moreover, energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) elemental mapping (Fig. 1g) of 0.1% PdNi sample verified that Pd atoms are highly dispersed on Ni nanoparticles rather than amorphous alumina. Besides, the AC-HAADF-STEM images (Fig. S14 in Supporting information) of 0.8% PdNi sample and 3% PdNi samples intuitively displayed the particle size of Pd, less than 3 nm and more than 6 nm, respectively.

CO adsorption in situ diffuse reflection infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (CO-DRIFTS) was further carried out to notarize the accurate existence form of Pd species of three bimetallic PdNi samples, since CO is a very sensitive probe for Pd species structures (Fig. 2b). The test details of CO-DRIFTS are described in the Experimental chapter of Supporting Information. Firstly, it is noted that for all PdNi bimetallic samples, two broad peaks appear near 1895 and 2057 cm−1, which are attributed to CO on Ni sites demonstrated in previous works [39,40]. In addition, the two shoulder peaks at 2085 and 1970 cm−1 can be attributed to linear CO on Pd0 and bridge-bonded CO on Pd sites caused by the formation of Pd clusters or NPs, respectively. Noteworthily, in order to intuitively analyze the linear CO on Pd, the profiles (Fig. 2c) of three PdNi bimetallic samples within 2010–2110 cm−1 are deconvoluted and fitted to two peaks of linear CO on Pd0 sites (~2085 cm−1) and linear CO on Ni sites (~2057 cm−1). For 0.1% PdNi sample, there is only linear CO on Pd0 (2085 cm−1) without any bridge-bonded CO signal (1970 cm−1), which convincingly demonstrates the successful synthesis of PdNi single atom alloy (SAA), well corresponding to AC-HAADF-STEM image (Fig. 1d) and the intensity profile (Fig. 1f). In contrast, although the peak of linear CO on Pd0 (~2085 cm−1) also exists in the 0.8% PdNi sample, the appearance of the shoulder peak (1970 cm−1) reveals the coexistence of large Pd ensembles and Pd single atoms in this sample. Furthermore, the shoulder peak (~1970 cm−1) of bridge-bonded CO on Pd ensembles for 3% PdNi sample shows stronger relative intensity compared with the linear CO peak (2085 cm−1), which represents the main existence species of this sample is large Pd ensembles or continuous Pd shell on the surface of Ni NPs, which accords well with the XRD pattern (Fig. S5) and AC-HAADF-STEM images (Fig. S14).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements (Fig. 2d and Fig. S6 in Supporting information) of Pd 3d and Ni 2p were employed to probe the surface elemental composition and investigate the electronic interaction between Pd and Ni. XPS spectrum of Pd 3d shows that the Pd electronic states of all PdNi bimetallic samples should be attributed to Pd0, which are well in line with CO-DRIFTS result (Fig. 2c). Compared with metallic Pd, the Pd 3d binding energy of 0.1% PdNi can be observed as a noteworthy upshift indexed to the electron transfer between Pd and Ni atoms. And the upshift of Pd 3d binging energy becomes weaker for 0.8% PdNi and 3% PdNi samples as the Pd existence transfers to large Pd ensembles or continuous Pd shell on the surface of Ni NPs, implying the electronic state tends to metallic Pd. Besides, the corresponding shift trend of the three samples is also shown in the XPS spectrum of Ni 2p (Fig. S6).

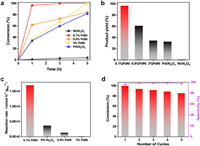

The Suzuki cross-coupling reaction between 4-bromoanisole and phenylboronic acid is employed as the model reaction to evaluate the catalytic performance of the 0.1% PdNi SAA sample and other control samples. The conversion of Ni/Al2O3 substrate in 5 h is only about 4% (Fig. 3a), demonstrating the substrate is inactive. And it is obvious that the reaction rate is rapidly improved due to the deposit of Pd. Although a uniform mass catalyst (0.02 g) was employed in the model reaction, and thus the Pd content of 0.1% PdNi SAA sample was much lower than other control samples, 0.1% PdNi SAA afforded a quite high 4-phenyltoluene yield (Fig. 3b) about 96.6% after 1 h at 80 ℃ with the excellent selectivity about 97%. Moreover, the reaction rate of Pd species in different samples was calculated to show the activity of Pd more directly. The reaction rate (Fig. 3c) of 0.1% PdNi SAA is approximately 17,032.25 mmol h−1 gPd−1, which is much higher than 0.8% PdNi (1267 mmol h−1 gPd−1), 3%PdNi (199.5 mmol h−1 gPd−1) and Pd/Al2O3 (3619 mmol h‒1 gPd−1) samples. Thus, 0.1% PdNi SAA has excellent catalytic performance for Suzuki cross-coupling reaction. It is supposed to be attributed to the advantages of PdNi SAA's unique electronic structure and high Pd atom utilization efficiency. Afterward, the durability and chemical stability of 0.1% PdNi SAA were investigated. The same conditions as the model reaction was selected, reacted at 80 ℃ for 1 h, then recovered the catalyst and reacted five cycles. It also has great reactivity (conversion 85%) for Suzuki coupling reaction after five cycles with consistently excellent selectivity (above 95%). The XRD patterns and TEM image (Fig. S12 in Supporting information) comparison between the fresh 0.1% PdNi sample and the sample after five cycles shows no obvious changes. And the Pd content of 0.1% PdNi SAA barely decreased after model reaction (Table S2 in Supporting information), which demonstrated that Pd is not leached to the solution in large quantities and the reaction occurs in a heterogeneous catalytic process. Furthermore, a reaction was performed according to the experiment in Fig. S15 (Supporting information). Firstly, the reaction of p-iodophenol and phenylboric acid is carried out according to the model reaction conditions, then the catalyst was removed by centrifugation. Finally, p-iodophenol and 4-fluorophenylboronic acid were added to react according to the model reaction conditions. The absence of 4-fluoro-4′-hydroxybiphenyl in products detected by GC–MS is further evidence that Pd leaching is negligible. Correspondingly, the Pd residue in product of all extension reactions was lower than the detection limit of ICP-OES.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Catalytic performance of the catalysts in Suzuki coupling reaction. (a) Conversion of 4-bromoanisole in Suzuki coupling reaction versus time over 0.1% PdNi SAA, 0.8% PdNi, 3% PdNi, Pd/Al2O3, and Ni/Al2O3. (b) Yields of the Suzuki coupling reaction of 4-methoxybiphenyl over 0.1% PdNi SAA, 0.8% PdNi, 3% PdNi, Pd/Al2O3, and Ni/Al2O3 after 1 h. (c) The reaction rate of 0.1% PdNi SAA, 0.8% PdNi, 3% PdNi, and Pd/Al2O3. (d) Recyclability and stability of 0.1% PdNi SAA. Reaction conditions: deionized water (5 mL), ethanol (5 mL), 0.1% PdNi SAA catalysts (20 mg), 4-bromoanisole (0.33 mmol), phenylboronic acid (0.66 mmol), and K2CO3 (0.5 mmol) at 80℃. | |

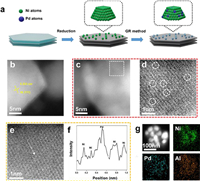

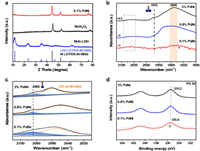

To investigate the substrate universality, a broad scope of aryl halide and phenylboric acid derivatives was selected to evaluate the 0.1% PdNi SAA catalytic performance (Table 1). Various aryl halide and phenylboric acid derivative as substrates can reach a high yield within 1 h, revealing the excellent substrate universality. Moreover, the 0.1% PdNi SAA was applied in Heck cross-coupling reactions and exhibited great reactivity (Table 2), which further demonstrated its great application prospect in cross-coupling reaction.

|

|

Table 1 Suzuki cross-coupling reactions for various aryl halides and arylboronic acids over 0.1% PdNi SAA. |

|

|

Table 2 Heck cross-coupling reactions for various aryl halides and arylboronic acids over 0.1% PdNi SAAa. |

Fig. 4 shows our proposed Suzuki reaction mechanism over PdNi SAA based on experimental results and catalyst structure characterization details. Here, every isolated Pd atom acts as an adsorption site for aryl halides due to the 100 percent dispersion, demonstrating Pd's ultra-high availability. In adsorption, the polar C-X bond (X = Cl, Br, I) in aryl halides is adsorbed by strong electrostatic interaction to the zero-valance Pd atom. And then, the electron-rich Pd weakens the C-X bonds as an electron donor, which is considered the rate-determining step for the reaction [26,41]. The electron-rich Pd is demonstrated as having a crucial role in reducing the activation energy of the reaction. Finally, the transmetallation and reductive elimination steps are followed by forming the final coupling products. It is worth noting that the electron-rich Pd and the ultra-high utilization of PdNi SAA lead to the high activity of the reaction.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Proposed mechanism. Proposed reaction paths for the Suzuki cross-coupling process over 0.1% PdNi SAA. | |

In summary, we applied SAAs for cross-coupling reactions and constructed PdNi SAA with high activity and stability by a two-step method consisting of Ni NPs obtained from the structural, topological transformation of LDHs followed by a galvanic replacement method. The successful synthesis of PdNi SAA was characterized by AC-HAADF-STEM, CO-DRIFTS, and XPS. The PdNi SAA exhibits extraordinary catalytic activity in Suzuki and Heck cross-coupling reactions. Noteworthily, the reaction rate of PdNi SAA is much higher than other control samples. It is obvious that the excellent catalytic performance of PdNi SAA is derived from the unique zero-valent Pd atoms with rich electrons and high atom utilization efficiency. Our work demonstrates the excellent application prospect of SAAs for cross-coupling reaction and provides a reference for other SAAs applications in various cross-coupling reactions.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the financial aid from National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2021YFB3500700), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22020102003, 22025506 and 22271274), and Program of Science and Technology Development Plan of Jilin Province of China (Nos. 20230101035JC and 20230101022JC).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108924.

| [1] |

N. Miyaura, A. Suzuki, Chem. Rev. 95 (1995) 2457-2483. DOI:10.1021/cr00039a007 |

| [2] |

A. Fihri, M. Bouhrara, B. Nekoueishahraki, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 40 (2011) 5181-5203. DOI:10.1039/c1cs15079k |

| [3] |

L. Yu, Y. Huang, Z. Wei, et al., J. Org. Chem. 80 (2015) 8677-8683. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.5b01358 |

| [4] |

Y. Su, Y. Li, C. Li, et al., ACS Omega 7 (2022) 29747-29754. DOI:10.1021/acsomega.2c02400 |

| [5] |

M. Niakan, Z. Asadi, M. Masteri-Farahani, ChemistrySelect 4 (2019) 1766-1775. DOI:10.1002/slct.201803458 |

| [6] |

Y. Yang, A.C. Reber, S.E. Gilliland Ⅲ, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 122 (2018) 25396-25403. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b07538 |

| [7] |

M. Niakan, M. Masteri-Farahani, Tetrahedron 108 (2022) 132655. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2022.132655 |

| [8] |

S. Jang, T. Kim, K.H. Park, Catalysts 7 (2017) 247. DOI:10.3390/catal7090247 |

| [9] |

Y. Zhang, H. Sun, Y. Yang, et al., Catal. Sci. Technol. 13 (2023) 3791-3795. DOI:10.1039/d3cy00529a |

| [10] |

G.C. Fu, Acc. Chem. Res. 41 (2008) 1555-1564. DOI:10.1021/ar800148f |

| [11] |

J. Ding, T. Rybak, D.G. Hall, Nat. Commun. 5 (2014) 5474. DOI:10.1038/ncomms6474 |

| [12] |

W.P. Mai, H.H. Wang, J.W. Yuan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 23 (2012) 521-524. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2012.02.004 |

| [13] |

X. Cui, J. Li, L. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 18 (2007) 625-628. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2007.04.014 |

| [14] |

M. Kim, J.C. Park, A. Kim, et al., Langmuir 28 (2012) 6441-6447. DOI:10.1021/la300148e |

| [15] |

J.D. Webb, S. MacQuarrie, K. McEleney, et al., J. Catal. 252 (2007) 97-109. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2007.09.007 |

| [16] |

B. Sreedhar, D. Yada, P.S. Reddy, Adv. Synth. Catal. 353 (2011) 2823-2836. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201100012 |

| [17] |

H.Q. Yang, Q.Q. Chen, F. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 676-680. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.06.022 |

| [18] |

K. Zhan, P. Lu, J. Dong, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 1630-1634. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.09.006 |

| [19] |

P. Puthiaraj, W.S. Ahn, Catal. Commun. 65 (2015) 91-95. DOI:10.1016/j.catcom.2015.02.017 |

| [20] |

X. Cui, W. Li, P. Ryabchuk, et al., Nat. Catal. 1 (2018) 385-397. DOI:10.1038/s41929-018-0090-9 |

| [21] |

A. Wang, J. Li, T. Zhang, Nat. Rev. Chem. 2 (2018) 65-81. DOI:10.1038/s41570-018-0010-1 |

| [22] |

Z. Chen, E. Vorobyeva, S. Mitchell, et al., Nat. Nanotechnol. 13 (2018) 702-707. DOI:10.1038/s41565-018-0167-2 |

| [23] |

X. Tao, R. Long, D. Wu, et al., Small 16 (2020) 2001782. DOI:10.1002/smll.202001782 |

| [24] |

H. Hu, J. Xi, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107959. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107959 |

| [25] |

J.R. Patel, A.U. Patel, Nanoscale Adv 4 (2022) 4321-4334. DOI:10.1039/d2na00559j |

| [26] |

T.N. Ye, Y. Lu, Z. Xiao, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 5653. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13679-0 |

| [27] |

Y. Lu, T.N. Ye, S.W. Park, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 14366-14374. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c03416 |

| [28] |

T. Zhang, A.G. Walsh, J. Yu, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 50 (2021) 569-588. DOI:10.1039/d0cs00844c |

| [29] |

X. He, H. Zhang, X. Zhang, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 5721. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-33442-2 |

| [30] |

G. Sun, Z.J. Zhao, R. Mu, et al., Nat. Commun. 9 (2018) 4454. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-06967-8 |

| [31] |

X. Zhang, G. Cui, H. Feng, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 5812. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13685-2 |

| [32] |

S. Luo, L. Zhang, Y. Liao, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2008508. DOI:10.1002/adma.202008508 |

| [33] |

M.J. Islam, M. Granollers Mesa, A. Osatiashtiani, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 299 (2021) 120652. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2021.120652 |

| [34] |

C.H. Chen, D. Wu, Z. Li, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1803913. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201803913 |

| [35] |

J. Kim, C.W. Roh, S.K. Sahoo, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 8 (2018) 1701476. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201701476 |

| [36] |

H. Xie, Y. Wan, X. Wang, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 289 (2021) 119783. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.119783 |

| [37] |

J. Shan, J. Liu, M. Li, et al., Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 226 (2018) 534-543. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.12.059 |

| [38] |

L. Zhang, A. Wang, J.T. Miller, et al., ACS Catal. 4 (2014) 1546-1553. DOI:10.1021/cs500071c |

| [39] |

W. Liu, H. Feng, Y. Yang, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 3188. DOI:10.3390/math10173188 |

| [40] |

H. Wang, Q. Luo, W. Liu, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4998. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12993-x |

| [41] |

H. Wei, X. Li, B. Deng, et al., Chin. J. Catal. 43 (2022) 1058-1065. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2067(21)63968-2 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35