b Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Materials Genome Engineering, Department of Physical Chemistry, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083, China;

c School of Mathematics and Physics, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083, China;

d Department of Condensed Matter Physics and Materials Science, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York 11973, United States

Energy storage and high efficiency utilization of energy have emerged as prominent research topics in recent years [1-4]. Ferroic dielectric capacitors have gained significant attention due to their indispensable roles in pulse power devices, offering advantages such as ultrahigh power density, ultrafast discharging speed, and excellent stability in complex environment [5-10]. With a focus on environmental preservation, extensive research has been conducted in the past decade to design and study energy storage capacitors based on lead free ferroic dielectrics [11-15]. Despite the effectiveness of introducing dielectric relaxation to enhance energy storage efficiency, a fundamental trade-off between energy storage density and efficiency persists in most ferroic dielectrics [5-22] due to the polarization structure characteristic of ferroelectrics (FEs) and antiferroelectrics (AFEs) [6,16-22].

Relaxor FEs undergo a gradual transition from nonergodic relaxor to ergodic relaxor eventually to superparaelectric state when heated, which results in a monotonic decrease in polarization hysteresis and leads to improved energy efficiency [7]. However, most relaxor FEs still face the challenges of limited energy storage density due to the weaken interactions between polar nanoregions (PNRs), the early polarization saturation process near the nonergodic-ergodic boundary, and the relatively low maximum polarization in superparaelectric zone [1,7,15]. To achieve excellent comprehensive energy storage properties in relaxor FEs, high-efficiency ergodic relaxor and superparaelectric state with highly dynamic PNRs are typically chosen as the matrix. On this basis, several strategies are employed at the same time to enhance the polarization response, such as high entropy strategy, local diverse polarization configurations, A-site lone electron pair effect [1-4,7,9,20-23].

In comparison, AFEs can be triggered to be a normal FE state by external electric fields, which allows for the generation of high energy storage density [24-30]. However, of reversible FE-AFE phase transition during discharging is accompanied by hysteresis, resulting in energy losses and relatively low efficiency [6,13,14,17,26]. Moreover, AFE capacitors face challenges such as the substantial volume expansion, strong polarization currents, and excessive heat production during AFE-FE phase transition, which increases the risk of breakdown and limits their application potential. The incorporation of relaxor behavior into AFEs offers a solution by breaking the long-range polarization ordering into nanosized AFE domains and diffusing both AFE-FE and FE-AFE phase transitions during charging and discharging processes, respectively. This leads to significant improvements in both energy storage density and energy efficiency [5,6,17-19,31-33]. Recent research suggests that relaxor AFEs exhibit notable advantages in terms of comprehensive energy storage properties, particularly in achieving ultrahigh energy storage density. However, it should be noted that the relaxor AFE-FE phase transition process still incurs non- negligible energy loss.

To address the trade-off between large energy storage density and high efficiency, a novel method is proposed as illustrated in Fig. S1 (Supporting information). This method combines the advantages of relaxor AFEs and relaxor FEs. By introducing a high-ferroelectricity material, BaTiO3 (BT), into a relaxor AFE matrix of NaNbO3-BiFeO3 (NN-BF), a unique relaxor AFE to relaxor FE crossover is achieved [18]. Remarkably, this NN-BF-BT ternary system exhibits a novel core-shell structure, where a high-efficiency relaxor FE core is surrounded by a high-density relaxor AFE shell. This configuration demonstrates both a high recoverable energy storage density of Wrec ~ 13.1 J/cm3 and an efficiency of η ~ 88.9%.

The (0.93-x)NN-0.07BF-xBT (NN-BF-xBT) ceramics were fabricated by a solid-state method using Na2CO3 (≥99.5%), BaCO3 (≥99.5%), Bi2O3 (≥99.5%), TiO2 (≥99.5%), Fe2O3 (≥99.5%) and Nb2O5 (≥99.5%) (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., China) as the starting materials. The mixed powder was synthesized through calcination at 850 ℃ for 5 h, and then the as-synthesized powders were high-energy ball milled at 700 rpm together with 0.5 wt.% PVB binder for 12 h. The sample discs were sintered by conventional sintering at 1200–1300 ℃ for 2 h. The ceramic samples were well polished, painted with silver paste and then fired at 550 ℃ for 30 min.

Temperature and frequency dependent dielectric permittivity was measured by using an LCR meter (E4980A, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). A ferroelectric test system (Precision multiferroelectric; Radiant Technologies Inc, Albuquerque, New Mexico) was used to measure the P-E hysteresis loops. The grain morphology was measured using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, S4800, HITACHI, Japan). Specimen for SEM measurement was well polished and then etched at 1100 ℃ for 30 min. X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements were performed with Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) radiation at an acceleration condition of 50 kV and 50 mA (STADI P; STOE, Germany). Rietveld refinement was taken by using GSAS II software. The domain morphology observation and SAED were carried out on a field-emission transmission electron microscope (FE-TEM, JEM-2100F, JEOL, Japan) operated at 200 kV. The high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) imaging and electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) mapping were performed on a 200 kV aberration-corrected JEM-ARM-200CF microscope equipped with a cold emission gun, double aberration correctors, and the GIF Quantum ER Energy Filter with Dual EELS and K3 camera. Specimens for TEM measurement were prepared by a conventional approach combining mechanical thinning and Ar+ ion-milling in a Gatan PIPS Ⅱ.

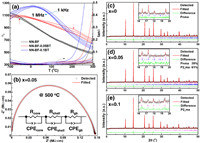

The temperature-dependent dielectric properties of NN-BF-xBT ceramics, as shown in Fig. 1a, exhibit clear relaxor behavior across all the studied samples. Interestingly, a prominent peak is observed in both x = 0 and x = 0.1 ceramics, while the x = 0.05 sample displays two distinct dielectric anomalies. This phenomenon is commonly observed in BT-based core-shell ceramics, where the composition segregation results in a difference in the Curie temperature between the core and shell [34-39]. With a continuous phase transition behavior upon heating, core-shell structure ceramics generally exhibit enhanced temperature stability of dielectric properties. To verify the presence of composition segregation or structural inhomogeneity, complex AC impedance measurements were conducted at high temperatures, and the results are presented in Fig. 1b and Fig. S2 (Supporting information). The clear asymmetry in Z''/Z''max-f peaks suggests the existence of multiple contributions to the impedance within the measured frequency range. This observation is further supported by fitting the results using a series R||CPE equivalent circuit model shown in Fig. 1b. Although a nearly single semicircle arc is observed, it is, in fact, an asymmetry semi-ellipse, indicating that an equivalent circuit model with at least three R||CPE units should be employed to accurately fit the impedance curve. Considering the significant frequency difference in the impedance response between oxygen ions and the compact microstructure with minimal pores, as displayed in Fig. S3 (Supporting information), these three contributions to the overall conduction likely originate from the grains and grain boundaries.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) Temperature and frequency dependent dielectric permittivity and loss of NN-BF-xBT ceramics. (b) The complex AC impedance and fitting semicircles at 500 ℃ for the x = 0.05 ceramic. Rietveld refinement of room-temperature XRD patterns of NN-BF-xBT ceramics: (c) x = 0, (d) x = 0.05 and (e) x = 0.1. The insets are locally enlarged superlattice diffractions in the range of 16°−20°. | |

The composition segregation would lead to heterogeneity in the phase structure. To investigate this, Rietveld refinement of XRD patterns was performed, and the optimal refinement results are shown in Figs. 1c-e. NN is a well-known perovskite oxide with a complex phase transition behavior under different conditions, with at least 10 different phases reported [40,41]. Therefore, distinguishing the phase structure in NN-based ceramics based solely on perovskite main XRD peaks is challenging. In addition to the structure symmetry caused by polarization displacement, another significant feature of these phases in NN-based materials is the complex oxygen octahedral tilt. Long-range ordered periodicity of anti-phase (-) and in-phase (+) tilts along three axes, represented as (ooo)/2 and (ooe)/2 type superlattice diffractions, respectively [42], would lead to different supercell structures in NN-based ceramics. Examples include the a−a−a− in the FE N phase, a−b+c− in the FE Q phase, a−b+a−/a−b−a− in the AFE P phase, a−b+c+ in the paraelectric S phase, and so on [41,42]. Therefore, the main characteristic used to identify these complex phases is the presence of superlattice diffractions, as shown in the insets of Figs. 1c-e for several typical examples. According to the previous studies [18], the addition of BF into NN would shift the P-R phase transition temperature to a lower value. When the BF content exceeds 6 mol%, an R-dominated phase with the Pnma space group can be detected at room temperature (RT), accompanied by evident dielectric relaxation behavior. Based on the Rietveld refinement results, the 0.93NN-0.07BF ceramic can be well identified as the AFE R phase with the Pnma space group, exhibiting a six-fold perovskite cell structure along the c axis. Apart from the polarization configuration, another important feature of the AFE R 2 × 2 × 6 supercell is the complex oxygen octahedral tilt system of a−b+c* (c* = A0CA0C, where A represents anticlockwise tilt, C represents clockwise tilt, and 0 represents zero tilt) [17,43]. Upon substituting 10 mol% of high-ferroelectricity BT for NN, the superlattice diffraction peaks arising from the six-fold AFE periodicity disappear, indicating a transformation into FE phase. Therefore, the XRD results of the x = 0.1 composition can be well fitted using an FE phase with the P21ma space group (Fig. 1e). In conjunction with the observed dielectric relaxation behavior, the x = 0.1 composition can be identified as an ergodic relaxor FE state at RT. In the crossover region between relaxor AFE and relaxor FE with increasing BT content, a phase boundary coexisting with Pnma and P21ma phases is achieved in the x = 0.05 composition (Fig. 1d). This phase boundary between relaxor AFE and relaxor FE is reported for the first time.

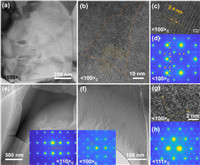

While the characteristics of superlattice diffractions in the NN-based ceramics allows for the identification of the average structure, which is quite different from the pseudo-cubic feature found in classical relaxor FEs, the nanosizing of domains can obscure much of the local structure information in XRD patterns. To elucidate the micro and local structure, TEM analysis was conducted on the studied samples (Fig. 2). In both normal FEs and AFEs, the presence of long-range ordered polarization and oxygen octahedral tilt would lead to the formation of macro/micro domains, which are then broken down into nanoscale domains or PNRs due to the influence of local random field resulting from compositional disorder along with the appearance of relaxor behavior. In the x=0 ceramic, although only a few microdomains can be observed, an irregular distribution of parallel nano stripes can be seen along the [100]C direction. This differs from the ellipsoidal or short stick shaped PNRs typically observed in traditional relaxor FEs, which are usually smaller than 20 nm in size. Notably, the hierarchical structure of AFE domains can still be detected in high resolution TEM (HRTEM) images (Figs. 2b and c) [13,17], where nanodomains with dimensions of tens of nanometers in size are composed by commensurate modulation stripes with a width -2.4 nm (equivalent to six lattice parameters of basic perovskite cubic cell). The presence of 1/6 type superlattice diffraction dots in Fig. 2d further confirms the existence of supercells composed by six-fold perovskite unit cells along the c axis, which is a characteristic feature of the AFE R phase in NN-based ceramics [43,44]. Combining these findings with the results of dielectric relaxation and Rietveld refinement, it can be concluded that the 0.93NN-0.07BF composition represents a relaxor AFE state with nanosized R phase domains.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Domain structure of relaxor AFE and relaxor FE samples. (a) Bright-field TEM image, (b, c) HR-TEM image and (d) SAED patterns of x = 0 ceramic along [100]C direction. Bright-field TEM image and SAED patterns along (e) [110]C and (f, g) [100]C directions respectively. (h) SAED pattern along [111]C direction of x = 0.1 ceramic. | |

Upon substituting BT, the hierarchical structure nanodomains is no longer observed in the x = 0.1 composition. Instead, irregular contrast related to the presence of PNRs can be detected in Figs. 2e and f. Additionally, the disappearance of 1/n (n>2) type diffraction dots (Figs. 2e-h), indicates the elimination of modulated polarization and/or oxygen octahedral tilt structure [44]. Simultaneously, (ooe)/2, (ooo)/2 and (oee)/2 types of superlattice diffraction dots can be detected, corresponding to the a−b+c− oxygen octahedral tilt feature of the FE P21ma phase. It should be noted that the 1/2 type diffraction dots are present at all equivalent positions, suggesting that the long-range ordering of oxygen octahedral tilt is disrupted, similar to the randomly distributed local polarization. This differs markedly from the domain structure observed in NN—CaZrO3 relaxor FEs with significant oxygen octahedral tilt, where ordered oxygen octahedral tilt forms micro ferroelastic domains, resulting in the scenario of partially occupied superlattice diffraction dots [16]. This discrepancy can be attributed to the larger tolerance factor exhibited by the studied NN-BF-BT ceramic compared to NN—CaZrO3 relaxor FEs, resulting in a smaller antiferrodistortion. In summary, the x = 0.1 sample can be characterized as a relaxor FE with short-range order of both polarization and oxygen octahedral tilt.

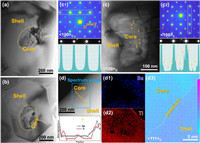

The composition of x = 0.05 exhibits a coexistence of AFE and FE states, as indicated by the dielectric properties and XRD results, suggesting a transition from relaxor AFE to relaxor FE with increasing BT content. To visualize the local structure distribution, comprehensive TEM investigations, including imaging and selected area electron diffraction (SAED), were conducted and presented in Fig. 3. A distinct core-shell structure is observed in most grains of the x = 0.05 ceramic, where stripe domains are clearly visible in the core regions, while the shell regions manifest weaker contrast. SAED patterns of the shell and core regions are shown in Figs. 3c1 and c2, respectively. The core regions display 1/6 type superlattice diffraction dots, corresponding to nano stripes with a width of ~10–20 nm. EELS quantification of a representative core-shell structure reveals the distributions of Ba and Ti elements, as shown in Fig. 3d. The core regions are found to be deficient in both Ba and Ti elements, that is BT phase, corresponding to a relaxor AFE phase inherited from NN-BF binary system. On the other hand, the enrichment of BT in the shell region leads to the formation of a relaxor FE phase, characterized by the absence of PNR structures and presence of only half superlattice diffraction dots. The formation of core-shell structure can be attributed to compositional heterogeneity during sintering process, likely arising from the significant difference in the respective optimum sintering temperatures of the constituents: NN, BF, and BT [45]. This leads to the formation of BF-rich (BT-deficient) regions (core regions), which are more reactive during initial stages of sintering, while the BT-rich regions (shell regions) are incorporated at later stages. Composition segregation is also expected to occur in compositions with higher BT content, such as the x = 0.1 ceramic. However, in the x = 0.1 composition, both the core and shell regions exhibit a relaxor FE state due to sufficient BT content, making it challenging to distinguish composition segregation features from domain structure detection. The core-shell structure observed in this studied composition is significantly different from the core-shell structures found in BT-based ceramic, despite both being related to composition segregation. In typical BT-based samples and some other relaxor FEs, distinct structures of a normal FE core and a relaxor FE shell (or vice versa) can be observed [46,47], where the local symmetry of both core and shell is actually identical, representing an FE state in nature. The main difference lies only in the scale of polarization ordering, specifically the size of domains [36-39,46,47]. In contrast, in the studied 0.88NN-0.07BF-0.05BT ceramic, significant differences are observed in terms of local symmetry, polarization configuration, oxygen octahedral tilt type, and domain size between core and shell regions. Therefore, this material can be regarded as a relaxor-AFE/relaxor-FE composite material.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Core-shell structure of NN-BF-0.05BT ceramic. (a-c) Bright-field TEM images measured at different grains of x = 0.05 ceramic along [100]C direction. SAED patterns measured at the (c1) shell and (c2) core regions of (c). (d) HAADF STEM: (d1, d2) Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) mapping images and (d3) atomic intensity mapping of atom columns around a typical core. | |

To evaluate the energy storage properties, the P-E loops of NN-BF-xBT ceramics are shown in Fig. 4a. In the x = 0 ceramic, although the additional relaxor AFE-FE phase transition contributes to a large polarization, a relatively large polarization hysteresis is also observed, leading to dissipation of a substantial amount of energy during discharging. Conversely, the relaxor FE sample with x = 0.1 exhibits a slim P-E loop with an ultrahigh energy efficiency of η>92%. Nevertheless, the early saturation of polarization limits further improvement in energy storage density under higher applied electric fields. The sample with a crossover composition of x = 0.05 demonstrates excellent overall energy storage properties, striking a balance between high recoverable energy storage density (Wrec ~ 13.1 J/cm3) and ultrahigh efficiency (η ~ 88.9%). These characteristics not only achieve a favorable equilibrium between high Wrec and ultrahigh η but also surpass the energy storage properties of most recently reported ceramic capacitors, as evident in Fig. 4b and Table S1 (Supporting information) [5-16,18-23,27,31-33,48-52].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Energy storage properties. (a) P-E loops of NN-BF-xBT ceramics. (b) A comparison of energy storage properties between studied samples and recently reported lead-free ceramics. | |

In the pursuit of excellent energy storage properties, researchers have designed various composite materials by combining the advantages of different components. For instance, combining polymers (or other linear dielectrics) with high breakdown strength and ferroic dielectrics with high dielectric permittivity has shown promise in achieving significant advancements in energy storage properties [34,35,53-55]. However, the fragile interfaces between different components often give rise to a series of problems that impede further improvements in energy storage properties. In this study, a core-shell structure is formed, where a strong interface is created within the same lattice, providing a primary foundation for achieving high breakdown strength and low leakage current. Remarkably, relaxor AFEs and relaxor FEs have been reported to exhibit advantages in terms of ultrahigh energy storage density and high efficiency, respectively. By combining the benefits of relaxor AFEs and relaxor FEs, it becomes possible to overcome the trade-off between energy storage density and efficiency.

In summary, this study systematically investigated the phase transition from relaxor AFE to relaxor FE in BT substituted NN-BF ceramics. The combination of Rietveld refinement of XRD, HR-TEM and SAED revealed the formation of a distinct core-shell structure in the crossover composition of 0.88NaNbO3–0.07BiFeO3–0.05BaTiO3 ceramic. The core region consisted of relaxor AFE domains, while the shell region comprised relaxor FE domains, resulting in the most remarkable energy storage properties. Benefiting from the complementary advantages of relaxor AFEs and relaxor FEs, high Wrec and η are simultaneously achieved in this core-shell sample. The study provides a promising approach for overcoming the trade-off between Wrec and η in ceramic capacitors.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52172181, 22105017) and Interdisciplinary Research Project for Young Teachers of USTB (No. FRF-IDRY-21–002).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108871.

| [1] |

H. Pan, S. Lan, S. Xu, et al., Science 374 (2021) 100-104. DOI:10.1126/science.abi7687 |

| [2] |

H. Qi, L. Chen, S. Deng, J. Chen, Nat. Rev. Mater. 8 (2023) 355-356. DOI:10.1038/s41578-023-00544-2 |

| [3] |

H. Pan, F. Li, Y. Liu, et al., Science 365 (2019) 578-582. DOI:10.1126/science.aaw8109 |

| [4] |

J. Li, Z. Shen, X. Chen, et al., Nat. Mater. 19 (2020) 999-1005. DOI:10.1038/s41563-020-0704-x |

| [5] |

M.H. Zhang, H. Ding, S. Egert, et al., Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 1525. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-37060-4 |

| [6] |

N. Luo, K. Han, M.J. Cabral, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 4824. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-18665-5 |

| [7] |

L. Chen, N. Wang, Z. Zhang, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2205787. DOI:10.1002/adma.202205787 |

| [8] |

G. Ge, C. Shi, C. Chen, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2201333. DOI:10.1002/adma.202201333 |

| [9] |

P. Zhao, Z. Cai, L. Chen, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 13 (2020) 4882-4890. DOI:10.1039/d0ee03094e |

| [10] |

Z. Lu, G. Wang, W. Bao, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 13 (2020) 2938-2948. DOI:10.1039/d0ee02104k |

| [11] |

X. Dong, X. Li, X. Chen, et al., Nano Energy 101 (2022) 107577. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107577 |

| [12] |

M. Zhang, H. Yang, Y. Lin, Q. Yuan, H. Du, Energy Stor. Mater. 45 (2022) 861-868. |

| [13] |

L. Zhao, Q. Liu, J. Gao, S. Zhang, J.F. Li, Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1701824. DOI:10.1002/adma.201701824 |

| [14] |

Y. Tian, L. Jin, H. Zhang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 4 (2016) 17279-17287. DOI:10.1039/C6TA06353E |

| [15] |

K. Wang, J. Ouyang, M. Wuttig, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 10 (2020) 2001778. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202001778 |

| [16] |

H. Qi, W. Li, L. Wang, et al., Mater. Today 60 (2022) 91-97. DOI:10.1016/j.mattod.2022.09.003 |

| [17] |

H. Qi, R. Zuo, A. Xie, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2019) 1903877. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201903877 |

| [18] |

J. Jiang, X. Meng, L. Li, et al., Energy Stor. Mater. 43 (2021) 383-390. |

| [19] |

S. Gao, Y. Huang, Y. Jiang, et al., Acta Mater. 246 (2023) 118730. DOI:10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118730 |

| [20] |

D. Li, D. Zhou, D. Wang, W. Zhao, Y. Guo, Z. Shi, Adv. Funct. Mater. 32 (2022) 2111776. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202111776 |

| [21] |

Q. Hu, Y. Tian, Q. Zhu, et al., Nano Energy 67 (2020) 104264. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2019.104264 |

| [22] |

P. Zhao, H. Wang, L. Wu, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 9 (2019) 1803048. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201803048 |

| [23] |

A. Xie, J. Fu, R. Zuo, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2204356. DOI:10.1002/adma.202204356 |

| [24] |

Z. Fu, X. Chen, Z. Li, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 3809. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-17664-w |

| [25] |

H. Wang, Y. Liu, T. Yang, S. Zhang, Adv. Funct. Mater. 29 (2018) 1807321. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201807321 |

| [26] |

W. Chao, L. Tian, T. Yan, Y. Li, Z. Liu, Chem. Eng. J. 433 (2021) 133814. |

| [27] |

S. Li, T. Hu, H. Nie, et al., Energy Stor. Mater. 34 (2021) 417-426. |

| [28] |

P. Gao, Z. Liu, N. Zhang, et al., Chem. Mater. 31 (2019) 979-990. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b04470 |

| [29] |

T. Zhang, Y. Zhao, W. Li, W. Fei, Energy Stor. Mater. 18 (2019) 238-245. DOI:10.4103/pm.pm_364_18 |

| [30] |

X. Liu, Y. Li, X. Hao, J. Mater. Chem. A 7 (2019) 11858-11866. DOI:10.1039/c9ta02149c |

| [31] |

J. Liu, P. Li, C. Li, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 17662-17673. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c01507 |

| [32] |

H. Chen, J. Shi, X. Dong, et al., J. Materiomics 8 (2022) 489-497. DOI:10.1016/j.jmat.2021.06.009 |

| [33] |

X. Wang, X. Wang, Y. Huan, C. Li, J. Ouyang, T. Wei, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 9330-9339. DOI:10.1021/acsami.1c23914 |

| [34] |

K. Bi, M. Bi, Y. Hao, et al., Nano Energy 51 (2018) 513-523. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.07.006 |

| [35] |

Q. Jin, L. Zhao, B. Cui, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 8 (2020) 5248-5258. DOI:10.1039/d0tc00179a |

| [36] |

H.M. Yu, S.H. Go, S.J. Chae, et al., Ceram. Inter. 49 (2023) 21695-21707. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.03.309 |

| [37] |

L. Chen, K. Hui, H. Wang, P. Zhao, L. Li, X. Wang, J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 39 (2019) 3710-3715. DOI:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2019.05.041 |

| [38] |

S.C. Jeon, C.S. Lee, S.J.L. Kang, J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 95 (2012) 2435-2438. DOI:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2012.05111.x |

| [39] |

H. Hao, H. Liu, S. Zhang, et al., Scripta Mater. 67 (2012) 451-454. DOI:10.1016/j.scriptamat.2012.05.046 |

| [40] |

S.K. Mishra, N. Choudhury, S.L. Chaplot, P.S.R. Krishna, R. Mittal, Phys. Rev. B 76 (2007) 024110. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevB.76.024110 |

| [41] |

H. Qi, G. Wang, Y. Zhang, et al., J. Chen, Acta Mater. 248 (2023) 118778. DOI:10.1016/j.actamat.2023.118778 |

| [42] |

A.M. Glazer, Acta Cryst. B 28 (1972) 3384. DOI:10.1107/S0567740872007976 |

| [43] |

H. Qi, A. Xie, J. Fu, R. Zuo, Acta Mater 208 (2021) 116710. DOI:10.1016/j.actamat.2021.116710 |

| [44] |

Z. Li, Z. Fu, H. Cai, et al., Sci. Adv. 8 (2022) eabl9088. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.abl9088 |

| [45] |

I. Calisir, D.A. Hall, J. Mater. Chem. C 6 (2018) 134. DOI:10.1039/C7TC04122E |

| [46] |

X. Zhou, G. Xue, Y. Su, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 458 (2023) 141449. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.141449 |

| [47] |

M. Acosta, L.A. Schmitt, L.M. Luna, et al., J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 98 (2015) 3405-3422. DOI:10.1111/jace.13853 |

| [48] |

A. Xie, R. Zuo, Z. Qiao, Z. Fu, T. Hu, L. Fei, Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (2021) 2101378. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202101378 |

| [49] |

G. Wang, J. Li, X. Zhang, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 12 (2019) 582-588. DOI:10.1039/c8ee03287d |

| [50] |

L. Zhang, M. Zhao, Y. Yang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 465 (2023) 142862. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2023.142862 |

| [51] |

W. Cao, R. Lin, X. Hou, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. (2023) 2301027. |

| [52] |

L. Liu, Y. Liu, J. Hao, et al., Nano Energy 109 (2022) 108275. DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2023.108275 |

| [53] |

H. Luo, X. Zhou, C. Ellingford, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 4424-4465. DOI:10.1039/c9cs00043g |

| [54] |

Q. Li, K. Han, M.R. Gadinski, G. Zhang, Q. Wang, Adv. Mater. 26 (2014) 6244-6249. DOI:10.1002/adma.201402106 |

| [55] |

Z.M. Dang, J.K. Yuan, S.H. Yao, R.J. Liao, Adv. Mater. 25 (2013) 6334-6365. DOI:10.1002/adma.201301752 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35