b State Key Laboratory of Natural Medicines, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China;

c Department of Pharmaceutics, School of Pharmacy, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 211198, China;

d Jiangsu Provincial Key Laboratory of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing 210009, China;

e School of Pharmaceutical Science, Nanjing Tech University, Nanjing 211816, China

Nanoparticles have been extensively used in drug delivery at tumor sites [1], but their limited penetration and retention capacity often lead to unsatisfactory anti-tumor effects [2,3]. To overcome these biological barriers, researchers have modified traditional nanocarriers by changing their geometric shape [4-6], particle size [1,4,7,8], and surface charge [7]. Particle size has become a crucial issue in this regard [4,9-12]. A new strategy has been developed that involves intelligent and size-adjustable nanoparticle preparation methods [1,13-16]. These methods enable nanoparticles to respond to enzymes [7,17,18], pH [19-22], light [23], temperature [19], oxygen [24], and reactive oxygen species (ROS) [25], etc., allowing them to aggregate in the deep part of the tumor and increase the retention effect of nanoparticles in the tumor [26-28]. Studies have shown that smaller nanoparticles possess stronger penetration ability but are also more quickly cleared from the body [7,29], which reduces their accumulation at the tumor site [30,31]. In contrast, larger nanomedicines can remain in the tumor site for longer periods but have difficulty penetrating the dense extracellular matrix [15,20,32,33]. In addition, larger particle sizes are prone to be captured and cleared during circulation in the body, and even if they remain in the tumor region, they are not easily taken up [34]. To solve the size dilemma and integrate the advantages of both large sizes and small sizes, a pH-sensitive size-changeable drug delivery system could be engineered by utilizing the acidic tumor microenvironment [35-37], to enhance tumor penetration and retention of nanoparticles, thus leading to enhanced drug accumulation and therapeutic impact [35,38], which is more intelligent and efficient compared to an invariable-size nanoparticle [35,39]. In this design, drugs that act on the tumor tissue are used, and the drugs can exert their effects without being taken up by the tumor cells.

Drugs that target tumor tissue usually act on the neovasculature in tumor tissue. Tumors form their blood supply by releasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a key driver of tumor growth, in a process known as neovascularization. Blood vessel formation is a critical step in the mechanism of tumor occurrence, development, and metastasis. Studies have shown that when the volume of tumor growth exceeds 1–2 mm3, a large number of blood vessels are produced around the tumor to supply the nutrients required for tumor growth [40]. Currently, targeted therapy for tumors using vascular targeting drugs mainly includes two categories of drugs: anti-angiogenic drugs and vascular disrupting agents. Anti-angiogenic drugs inhibit the formation of tumor neovasculature by suppressing VEGF and other pro-angiogenic factors, while vascular disrupting agents act on the established blood vessels in the tumor, causing rupture and obstruction of blood vessels in that area, thereby blocking the blood circulation in that area and inducing necrosis within the tumor. In this study, we used a thrombin inhibitor, dabigatran etexilate, as an anti-angiogenic drug. Dabigatran etexilate is absorbed and converted into dabigatran in the body, exerting its anticoagulant effects. Its principle is based on the specific binding of dabigatran to the site where fibrinogen is cleaved by thrombin, preventing fibrinogen from being converted to fibrin, thereby blocking the final step of thrombus formation and inhibiting neovascularization [41-46].

To achieve the above goals, we propose to design a nanoparticle platform with variable sizes that remain small in physiological environments and enlarge in tumor environments for drug release. Based on our previous design of (HE)n and (RG)n [47,48], the (HE)n was designed as a masking peptide to cationic cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) conferred the pH-sensitive. Furthermore, we found that the pH sensitivity of our designed activatable cell-penetrating peptides (ACPPs) was reversible. Therefore, we hope to be able to use the reversible pH response to prepare the size-switchable polymer micelles. In this work, two peptide sequences of (HE)6CC and (RG)6CC were connected to the ends of amphiphilic polymers to prepare mixed micelles. In normal physiological environments, the two peptide sequences are attracted to each other electrostatically, resulting in small particle sizes [47]. In the tumor microenvironment, the histidine residues are protonated, causing electrostatic repulsion between the two peptide sequences and enlargement of the micelles for drug release. To prevent the micelles from dissociating and releasing drugs back into the bloodstream, we introduce disulfide bonds at the ends of the peptides for crosslinking the micelles, which increases the stability of the mixed micelles without hindering drug release. We designed a size-switchable core-crosslinked polyion complex micelle (cPCM) that responds to the tumor microenvironment with reversible particle size. The mechanism is illustrated in Scheme 1. Firstly, synthesize the polymers (Scheme 1A), secondly, prepare the drug-loaded cPCM (Scheme 1B), and then DE@cPCM was injected into mice through the tail vein to participate in the internal circulation (Scheme 1C). When DE@cPCM reaches the tumor microenvironment, it releases the dabigatran etexilate (DE) (Scheme 1D). The drug competes with thrombin in the tumor area to competitive inhibition (Scheme 1E), thus inhibiting angiogenesis in the tumor area, making the tumor lack and inhibiting tumor growth (Scheme 1F).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. The schematic illustrates the preparation of cPCM and their delivery and action in vivo. (A) Synthesis of polymers. (B) Preparation of drug-loaded cPCM. (C) The circulation process of DE@cPCM in blood. (D) The process of DE@cPCM responding to the pH change in the tumor microenvironment and undergoing size variation. (E) Competition-based angiogenesis inhibition. (F) Starvation-induced tumor growth inhibition. | |

The typical 1H-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of copolymers were shown in Fig. S2A (Supporting information). 1H NMR spectra were recorded using a Bruker (AVANED) AV-300 spectrometer at 300 MHz, using tetramethyl silane (TMS) as an internal standard. The integrals of the peaks corresponding to the poly(D,L-lactide) (PLA) methine protons (d 5.18 ppm) and the poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) methylene protons (d 3.62 ppm) were applied to the determination of the weight ratio of PLA to PEG and calculation of the average number molecular weight of PLA. The carboxyl peak was observed at 12 ppm, suggesting the mPEG-PLA-COOH was synthesized successfully. Using the (HE)6CC and (RG)6CC as control respectively, we observed the characteristic peaks appear in mPEG-PLA-(HE)6CC and mPEG-PLA-(RG)6CC, also suggesting the peptides were conjugated on the polymers successfully.

Thermal behaviors of synthesized polymer were analyzed by differential scanning calorimeter (DSC 250, TA) at temperatures ranging from 25 ℃ to 250 ℃ at a heating ramp of 10.0 ℃/min. As shown in Fig. S2B (Supporting information), mPEG2000 and D,L-lactide (D,L-LA) have different melt points. The mixture of mPEG2000 and D,L-LA have two melt points, while mPEG-PLA and mPEG-PLA-COOH exhibited an endothermic peak as a melting point at 41 and 43 ℃, respectively. mPEG-PLA-(HE)6CC and mPEG-PLA-(RG)6CC have smaller melt points compare to mPEG-PLA. The results indicate the mPEG-PLA, mPEG-PLA-COOH, mPEG-PLA-(HE)6CC, and mPEG-PLA-(RG)6CC were synthesized successfully.

Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra were obtained from Thermo Fisher Technology Co., Ltd. using the KBr method (Fig. S2C in Supporting information). The hydroxyl peak in mPEG-PLA was observed at 3500 cm−1, while it disappeared in mPEG-PLA-COOH due to being replaced by the carboxyl group. mPEG-PLA-(HE)6CC and mPEG-PLA-(RG)6CC exhibited the peptide peaks with the (HE)6CC and (RG)6CC as control, respectively. The FT-IR further confirmed mPEG-PLA, mPEG-PLA-COOH, mPEG-PLA-(HE)6CC, and mPEG-PLA-(RG)6CC were synthesized successfully.

Gel permeation chromatography was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography from Shimadzu Corporation, Japan, equipped with a detector of Shimadzu RID-10A. As shown in Fig. S3 (Supporting information), the result demonstrates excellent calibration of the GPC, and the mass of the polymer has been calculated, as shown in Table S1 (Supporting information). The data suggests that the GPC method used in this study is reliable and accurate in determining the molecular weight and mass of the polymer samples.

We investigated the preparation of smart-responsive micelles for the tumor acidic microenvironment. These micelles can achieve intelligent release by undergoing particle size changes under different pH conditions. Therefore, we synthesized a series of cPCM with varying composition ratios and examined the optimal formulation of cPCM. Detailed results are shown in Figs. 1A–D. The results demonstrate that cPCM prepared with different carrier ratios have various particle sizes under different pH conditions. The cPCM in Figs. 1C and D did not show significant differences in particle size changes under different pH conditions. However, as the proportion of mPEG-PLA increased, the expansion effect of particle size under the acidic condition became poorer. Therefore, it is not suitable to further increase the proportion of mPEG-PLA in the formulation. To determine the optimal formulation, we prepared DE@cPCM using the same method and examined the drug loading and encapsulation efficiency. The results are presented in Table S2 (Supporting information). The table shows that these series of cPCM also have different drug contents and entrapment efficiencies. When the ratio of cPCM was 6:1:1, it exhibited the highest drug loading and encapsulation efficiency. This could be attributed to the increased hydrophobicity of the core of the polymer micelles with higher content of mPEG-PLA, leading to higher drug loading and encapsulation efficiency. Considering the particle size changes, drug loading, and encapsulation efficiency, we ultimately selected the formulation ratio of 6:1:1 for further investigation.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Revserbily size-switchable characteristic of the cPCM as the pH variation. (A–D) Different mass radios of cPCM were adjusted to different pH. (E) TEM images of cPCM reciprocating pH adjustment, scale bar is 200 nm. (F) Particle size of cPCM reciprocating pH adjustment. (G) Stability of DE@PM, DE@PCM and DE@cPCM. (H) In vitro release of DE@cPCM at pH 6.5 and 7.4 with or without 10 mmol/L GSH. mean ± standard deviation (SD), n = 3. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. pH 7.4. | |

Furthermore, it is of paramount importance that the cPCM we aim to prepare exhibits reversible size swell and shrink. In other words, the polymer micelles should resist engulfment in normal physiological environments, allowing them to reach the tumor microenvironment where the cPCM expands and releases the drug. Moreover, they should enhance the retention time of micelles in the tumor region. Even when pumped back into the normal physiological environment under the influence of tumor stroma pressure, the particle size of the polymer micelles should shrink without disintegration, enabling them to return to the tumor microenvironment and exert their therapeutic effect once again, thereby enhancing the bioavailability of the drug. Therefore, to achieve a more pronounced and significant size swell effect, we selected three pH values, namely 6.0, 6.5, and 7.4, by adjusting the solution pH repeatedly. The reversible changes in particle size of the cPCM were examined using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS) techniques. As shown in Fig. 1E, we observed the morphology of cPCM using TEM and found that the particle size of cPCM changed reversibly with pH. Under pH 7.4 conditions, the particle size was approximately 50 nm. When the pH was adjusted to 6.5, the particle size increased to approximately 130 nm. However, when the pH was readjusted back to 7.4, the particle size returned to its initial size. This indicates that the prepared cPCM exhibits reversible changes in particle size. To observe the expansion effect of cPCM more prominently, we further adjusted the pH to 6.0. As a result, a more significant size expansion was observed, further confirming the pH-responsive and reversible nature of cPCM. As shown in Fig. 1F, the results obtained from DLS were consistent with those from TEM, providing further evidence of the reversible particle size changes of cPCM.

Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) is widely used to distinguish synthetic polymers and their physical mixture [49], the encapsulation of DE in cPCM was investigated using DSC. From the DSC thermograms (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), cPCM exhibited an endothermic peak of around 45 ℃, while the endothermic peaks of around 50, 75, 115, and 125 ℃ belong to the DE. The physical mixture composed of cPCM and DE exhibited all the endothermic peaks described above. However, the endothermic peak of DE@cPCM only exhibited an endothermic peak of around 45 ℃, indicating that DE was loaded in the cPCM.

To assess the stability of DE@cPCM, we prepared DE@PCM and DE@PM as controls. The polymer micelles from different groups were first diluted to the same concentration, and the particle sizes of the different groups were measured at different time points. As shown in Fig. 1G, the DE@PM, DE@PCM, and DE@cPCM have the same particle size at 0 h, but the particle size of DE@PM and DE@PCM became larger obviously at 2 h, indicating the DE was leaked from DE@PM and DE@PCM. However, the particle size of DE@cPCM without significant difference within 24 h indicated that the disulfide-crosslinking increased the stability of DE@cPCM.

To further investigate whether the stability of DE@cPCM is attributed to disulfide crosslinking, we employed a progressive dilution method to demonstrate the enhanced stability resulting from disulfide crosslinking. If the particle size does not show significant changes with continuous dilution, it indicates that the disulfide crosslinked DE@cPCM exhibits improved stability. As shown in Fig. S5 (Supporting information), DE@cPCM solution (1 mg/mL) was prepared and diluted, the dilution has not affected the particle size of DE@cPCM, further confirming that disulfide-crosslinking could increase the stability of micelles.

By progressively diluting DE@cPCM and examining the changes in particle size, we were able to provide partial evidence of its stability. However, to further confirm that this stability is attributed to disulfide crosslinking, we prepared DE@PCM as a control. By comparing the behavior of DE@cPCM with DE@PCM, we can provide further evidence that disulfide crosslinking enhances the stability of DE@cPCM. As shown in Fig. S6A (Supporting information). Prior to the addition of serum, both DE@PM and DE@cPCM exhibited smaller initial particle sizes. However, upon the introduction of serum at 0 h, the particle size of DE@PM immediately increased, whereas DE@cPCM remained unchanged. Notably, significant changes in particle size for DE@cPCM were observed only after 8 h, although these changes were considerably smaller in magnitude compared to those in DE@PM. This observation indicates that within a serum environment, DE@cPCM demonstrates greater stability in comparison to DE@PM.

DE@PCM at pH 7.4 the particle size was 48 nm (Fig. S6B in Supporting information), which was slightly larger than that of DE@cPCM (Fig. S6D in Supporting information), possibly because the lack of disulfide-crosslinking reduced compact strength of the self-assembled DE@PCM. When the pH changed to 6.5, the particle size of DE@PCM become 498 nm (Fig. S6C in Supporting information), the result indicated that no disulfide-crosslinking of the DE@PCM was unstable. At pH 7.4, the particle size of DE@cPCM was measured as 32 nm (Fig. S6D), and when the pH was lowered to 6.5, the particle size of DE@cPCM increased to 150 nm (Fig. S6E in Supporting information). It was observed that the DE@cPCM size was enlarged as the pH decreased, and a uniform particle size distribution was observed. When 10 mmol/L of glutathione (GSH) was added to the phosphate buffered saline (PBS) solution at pH 6.5, the DE@cPCM undergoes partial disintegration (Fig. S6F in Supporting information), indicating that the DE@cPCM could respond to GSH. The data also indicated that the disulfide-crosslinking could increase the stability of DE@cPCM. The above results show that the DE@cPCM we designed and prepared can intelligently respond to the pH environment, and the disulfide bonds can not only increase the stability of the DE@cPCM but also make the DE@cPCM intelligently respond to the glutathione environment.

The DE@cPCM we prepared exhibits pH-responsive changes in particle size, which can impact drug release. Therefore, we investigated the release behavior of DE@cPCM under different media conditions. As shown in Fig. 1H, DE was not detected in the medium with pH 7.4 within 1 h, indicating that the DE@cPCM was stable under physiological conditions. In the medium with pH 7.4 with 10 mmol/L GSH, the drug release was increased due to the disulfide bond breakage in the DE@cPCM, and the stability of the DE@cPCM decreased. In the medium with or without GSH at pH 6.5, the drug release was relatively faster than at pH 7.4 in the first 8 h suggesting the pH-responsive release behavior of the DE@cPCM. After 8 h, the cumulative release in the two media was the same. The release rate of the DE@cPCM was affected by both pH and GSH. The results indicate that the designed cPCM holds promising potential for a wide range of applications, providing a technological platform for the subsequent synergistic release of drugs inside and outside cells. The results demonstrate that the designed cPCM exhibits promising potential for a wide range of applications, providing a technological platform for the subsequent synergistic release of therapeutics inside and outside cells. It can respond to extracellular pH changes as well as intracellular GSH changes, enabling the sequential release of drugs targeting the extracellular and intracellular environments. This dual-action approach enhances the therapeutic efficacy of treating diseases, particularly in the context of tumor treatment.

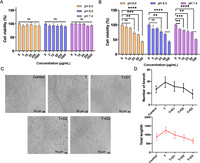

To assess the safety of the drug formulation, we conducted separate evaluations of the cytotoxicity of the carrier materials and the final formulation. As shown in Fig. 2A, the results revealed that the cell viability remained largely unaffected after 24 h incubation with cPCM of varying pH and concentrations, indicating the favorable safety profile of the cPCM carrier material. Additionally, Fig. 2B demonstrated that the cytotoxicity of DE@cPCM exhibited dose-dependent characteristics under different pH conditions.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Cytotoxicity of cPCM (A) and DE@cPCM (B) at pH 6.0, 6.5 and 7.4 on 4T1-luc cells for 24 h. (C) Representative pictures of tube-forming experiments (T: 50 ng of thrombin; D1: 50 ng of DE; D2: 100 ng of DE; D3: 200 ng of DE). (D) Quantitative analysis on the number of branch and total tube length of HUVECs after treatment. mean ± SD, n = 9. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. | |

The in vitro antiangiogenetic effect of DE@cPCM was estimated using the tube formation assay. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were incubated with thrombin, and the mixture of thrombin and the DE@cPCM, respectively, followed by the microscopic observation. Thrombin, a pivotal terminal enzyme of coagulation, promotes angiogenesis and simulates tumor growth and metastasis. Incubation with thrombin resulted in the formation of an extensive honeycomb-like structure by HUVECs (Fig. 2C), which is indicative of the angiogenesis-promoting effect of thrombin. The released DE could significantly inhibit the thrombin-stimulated tube formation of HUVECs, as confirmed by the quantitative analysis showing both a reduced number of branch and decreased total tube length (Fig. 2D), which suggests that DE has a powerful anti-angiogenesis capability by acting on thrombin directly with a high binding affinity and selectivity.

Animals were provided by Qinglongshan Animal Center (Nanjing, China), and all animal experiments were implemented according to the National Institute and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of China Pharmaceutical University. As shown in Fig. 3A, all treated groups reduced the tumor volume when compared to the PBS group. The tumor volume of the DE@cPCM group was significantly reduced at 16 days post-injection compared to the free drug group and DE@PCM group, suggesting the peptide modification exhibited an advance in anti-tumor efficiency. As shown in Fig. 3B, there was no significant difference in the body weight of the different mice, indicating that all groups were safe. The survival period of DE@cPCM was about 1.2-fold compared to the free drug group (Fig. 3C), indicating that DE@cPCM was capable of prolonging the survival of the mice. The intertumoral expression level of CD31 plays a crucial role during angiogenesis, the CD31 was evaluated using immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Fig. 3D, DE@cPCM significantly reduced anti-CD31 staining density compared to the PBS groups, which is substantial evidence of the vascularization inhibition in tumor tissue by DE@cPCM. As confirmed by the quantitative analysis showing reduced vessel shape (Fig. 3E), the result shows that DE possesses the ability to inhibit angiogenesis. Hematoxylin-eosinstaining (H&E) staining showed that the DE@cPCM can significantly accelerate cell apoptosis and necrosis (Fig. 3F). Meanwhile, the terminal uridine nucleotide end labeling (TUNEL)-based immunohistochemical analysis of the tumor revealed that the DE@cPCM had the highest level apoptotic of cells compared with other formulations (Fig. 3F).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. In vivo therapeutic efficacy in 4T1 tumor-bearing BALB/c mice. (A) Tumor volume change profiles after intravenous injection of PBS, Free DE, DE@PM, and DE@cPCM. mean ± SD, n = 6. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 vs. DE@cPCM. (B) Body weight changes after treatment with PBS, Free drug, DE@PM, and DE@cPCM. ns, not significant. (C) Survival rates of tumor-bearing BALB/c mice after treatment with PBS. Free DE, DE@PM, and DE@cPCM. (D) Images of blood vessels stained with CD31 antibody (red) in the tumor regions on Day 18 after treatment. The white arrow symbols represent the tumor blood vessels. Scale bar: 100 µm. (E) Quantitative analysis on blood vessels after treatment. mean ± SD, n = 6. **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001 vs. PBS; ns, not significant. (F) Representative images of tumor sections separated from mice stained by H&E and TUNEL. Scale bar: 100 µm. (G) H&E sections of heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney of mice after treatment of DE@cPCM. Scale bar: 50 µm. | |

According to Fig. S7A (Supporting information), cPCM and DE@cPCM have colors much lower than the positive control tube No. 7. According to Fig. S7B (Supporting information), the hemolysis rates of cPCM and DE@cPCM are below 2% and 8%, respectively. These results indicate a high level of safety for the cPCM and DE@cPCM. Finally, after treatment with DE@cPCM, the mice were sacrificed and their heart, liver, spleen, lung, and kidney were stained with H&E (Fig. 3G). The results showed that the DE@cPCM has good safety.

In brief, we have successfully developed an intelligent cPCM that exhibits reversible changes in particle size. These micelles are capable of enhancing their penetration into tumor tissues while simultaneously reducing their clearance from the tumor site. Under normal physiological conditions, the smaller size of DE@cPCM reduces the endothelial phagocytic effect, and upon reaching the tumor area, the pH decreases, causing an enlargement of the cPCM particle size, facilitating better drug release in the tumor region. Due to the higher interstitial pressure within the tumor, upon introduction into the normal physiological environment, the DE@cPCM particle size diminishes, leading to reduced drug release. This innovative design addresses the challenge of balancing tumor penetration and retention and may pave the way for future research on intracellular and extracellular co-administration.

The unique properties of these polymer micelles make them promising candidates for targeted drug delivery to tumors. By altering their particle size, we can optimize their pharmacokinetic profile and improve their overall efficacy. Additionally, this design could be adapted for the co-delivery of multiple therapeutic agents, enabling synergistic treatment approaches.

Our findings provide valuable insights into the development of advanced drug delivery systems, and could potentially improve patient outcomes in the future. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the mechanisms underlying the reversible particle size changes in these micelles and to explore their potential applications in various biomedical fields.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentThis project was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81972894, 22278442, 82273882).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109110.

| [1] |

F. Xu, X. Huang, Y. Wang, S. Zhou, Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) e1906745. DOI:10.1002/adma.201906745 |

| [2] |

J. Shinn, N. Kwon, S.A. Lee, Y. Lee, J. Pharm. Investig. 52 (2022) 427-441. DOI:10.1007/s40005-022-00573-z |

| [3] |

Z. Sun, W. Zhang, Z. Ye, et al., Nanoscale 14 (2022) 17929-17939. DOI:10.1039/d2nr04200b |

| [4] |

W. Zhang, R. Taheri-Ledari, F. Ganjali, et al., RSC Adv. 13 (2022) 80-114. DOI:10.5539/elt.v15n6p80 |

| [5] |

R. Zener, H. Yoon, E. Ziv, et al., Cardiovasc. Intervent. Radiol. 42 (2019) 569-576. DOI:10.1007/s00270-018-02160-y |

| [6] |

L. Xu, Y. Wang, C. Zhu, et al., Theranostics 10 (2020) 8162-8178. DOI:10.7150/thno.45088 |

| [7] |

Y. Yu, C. Zu, D. He, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 586 (2021) 391-403. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2020.10.103 |

| [8] |

H. Chen, Q. Guo, Y. Chu, et al., Biomaterials 287 (2022) 121599. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2022.121599 |

| [9] |

R. Wang, X. Wang, X. Jia, et al., Int. J. Pharm. 588 (2020) 119799. DOI:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119799 |

| [10] |

W. Xu, M. Zhou, Z. Guo, et al., Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 206 (2021) 111912. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2021.111912 |

| [11] |

C. Li, H. Guan, Z. Li, et al., Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces 196 (2020) 111303. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.111303 |

| [12] |

Z. Li, B.C. Ye, R.Y. Xie, et al., Chin. J. Hepatol. 30 (2022) 612-617. |

| [13] |

W. Yu, R. Liu, Y. Zhou, H. Gao, ACS Cent. Sci. 6 (2020) 100-116. DOI:10.1021/acscentsci.9b01139 |

| [14] |

X. Wang, C. Li, Y. Wang, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 12 (2022) 4098-4121. DOI:10.3390/electronics11244098 |

| [15] |

X. Ma, X. Chen, Z. Yi, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 26431-26442. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c04698 |

| [16] |

X. Zhang, X. Chen, J. Song, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) e2003752. DOI:10.1002/adma.202003752 |

| [17] |

J. Huang, Z. Xiao, Y. An, et al., Biomaterials 269 (2021) 120636. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.120636 |

| [18] |

J. Shen, M. Ma, M. Shafiq, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202113703. DOI:10.1002/anie.202113703 |

| [19] |

K. Thirupathi, T.T.V. Phan, M. Santhamoorthy, V. Ramkumar, S.C. Kim, Polymers 15 (2022) 36616517. |

| [20] |

H.Y. Tanaka, T. Nakazawa, A. Enomoto, A. Masamune, M.R. Kano, Cancers 15 (2023) 36765684. |

| [21] |

Q. Li, D. Fu, J. Zhang, et al., J. Biomater. Appl. 36 (2021) 579-591. DOI:10.1177/0885328220988071 |

| [22] |

L. Zhai, C. Luo, H. Gao, et al., Int. J. Nanomed. 16 (2021) 3185-3199. DOI:10.2147/ijn.s303874 |

| [23] |

M. Pokharel, K. Park, J. Drug Target 30 (2022) 368-380. DOI:10.1080/1061186x.2021.2005610 |

| [24] |

Y. Li, S. Feng, P. Dai, et al., J. Control Release 342 (2022) 201-209. DOI:10.3390/genes13020201 |

| [25] |

Y. Zhang, J. Zhao, L. Zhang, et al., Nanotoday 49 (2023) 101798. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2023.101798 |

| [26] |

H. Yan, Y. Zhang, Y. Zhang, et al., Biomater. Sci. 10 (2022) 6583-6600. DOI:10.1039/d2bm01291j |

| [27] |

B. Wu, M. Li, L. Wang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. B 9 (2021) 4319-4328. DOI:10.1039/d1tb00396h |

| [28] |

X. Qian, X. Xu, Y. Wu, et al., J. Control. Release 346 (2022) 193-211. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.04.006 |

| [29] |

S. Bai, Y. Zhang, D. Li, et al., Nano Today 36 (2021) 101038. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101038 |

| [30] |

I.V. Zelepukin, A.V. Yaremenko, M.V. Yuryev, et al., J. Control. Release 326 (2020) 181-191. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.07.014 |

| [31] |

L. He, N. Zheng, Q. Wang, et al., Adv. Sci. 10 (2022) e2205208. |

| [32] |

L. Xiao, Z. Ding, X. Zhang, et al., ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 8 (2022) 140-150. DOI:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.1c01122 |

| [33] |

Z. Yi, G. Chen, X. Chen, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12 (2020) 33550-33563. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c10282 |

| [34] |

L. Li, W.S. Xi, Q. Su, et al., Small 15 (2019) e1901687. DOI:10.1002/smll.201901687 |

| [35] |

R. Liu, C. Luo, Z.Q. Pang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107518. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.05.032 |

| [36] |

Z.Q. Shi, Q.Q. Li, L. Mei, Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 1345-1356. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.03.001 |

| [37] |

P. Mi, Theranostics 10 (2020) 4557-4588. DOI:10.7150/thno.38069 |

| [38] |

N.M. AlSawaftah, N.S. Awad, W.G. Pitt, G.A. Husseini, Polymers 14 (2022) 14050936. DOI:10.3390/polym14050936 |

| [39] |

B. Ghosh, S. Biswas, J. Control Release 332 (2021) 127-147. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2021.02.016 |

| [40] |

F. Hillen, A.W. Griffioen, Cancer Metast. Rev. 26 (2007) 489-502. DOI:10.1007/s10555-007-9094-7 |

| [41] |

A. Metelli, B.X. Wu, B. Riesenberg, et al., Sci. Transl. Med. 12 (2020) eaay4860. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.aay4860 |

| [42] |

B. Zhang, Z. Pang, Y. Hu, Thromb. Res. 187 (2020) 186-196. DOI:10.1016/j.thromres.2020.01.019 |

| [43] |

K. Shi, H. Damhofer, J. Daalhuisen, et al., Mol. Med. 23 (2017) 13-23. DOI:10.2119/molmed.2016.00214 |

| [44] |

D. Chen, X. Qu, J. Shao, W. Wang, X. Dong, J. Mater. Chem. B 8 (2020) 2990-3004. DOI:10.1039/c9tb02957e |

| [45] |

Z. Liu, Y. Zhang, N. Shen, et al., Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 183 (2022) 114138. DOI:10.1016/j.addr.2022.114138 |

| [46] |

J. Yin, X. Wang, X. Sun, et al., Small 17 (2021) e2105033. DOI:10.1002/smll.202105033 |

| [47] |

Y. Wang, L. Huang, Y. Shen, et al., Int. J. Nanomed. 12 (2017) 7963-7977. DOI:10.2147/IJN.S140573 |

| [48] |

Y. Tian, G. Mi, Q. Chen, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 43411-43428. DOI:10.1021/acsami.8b15147 |

| [49] |

L. Huang, Y. Wang, X. Ling, et al., Carbohydr. Polym. 159 (2017) 178-187. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.11.094 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35