Fungal polyketides are a group of natural products that exhibit structural diversity and display a wide range of pharmaceutical activities [1–5]. They are usually synthesized by standalone polyketide megasynthases, such as highly reducing polyketide synthases (hrPKSs) for the formation of macrocyclic or acyclic highly reduced family compounds [6–8], or non-reducing polyketide synthases (nrPKSs) for the yield of aromatic products [9]. To increase the structural complexity and diversity, a general strategy is to introduce different functional groups on the polyketide skeleton, which is usually installed by a variety of post-tailoring enzymes like cyclase [10], oxidoreductase [11,12], free radical enzyme [13,14] and so on.

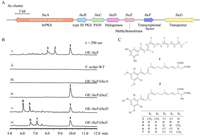

Apart from the above-mentioned subsequent tailoring steps, an alternative structural derivation of the polyketides, especially focusing on the variation of skeletons of highly reducing polyketides, mainly depends on the collaboration of hrPKSs with different synthases, for instance: (1) combination of hrPKS with nrPKS leads to the formation of alkylresorcinol radicicol, or azaphilones chaetoviridins and asperfuranone, which contain both reduced and aromatic polyketide features (Fig. 1A and Fig. S2A in Supporting information) [15–18] (2) two hrPKSs can prepare polyketide parts independently, and integrate them together to generate the product finally, which illustrates lovastatin and gregatin A as the example (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2B in Supporting information) [19–21] (3) collaboration of hrPKS and nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) can synthesize hybrid compounds, which incorporates amino acid moiety into polyketide such as pyrrocidines, equisetin, and thermolides (Fig. 1C and Fig. S2C in Supporting information) [22–24] (4) hybridization of hrPKS and terpene cyclase (TC) can produce meroterpenoids as calidoustenes or fumagillin (Fig. 1D and Fig. S2D in Supporting information) [25,26].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Representative hybrid strategies expand the structural diversity of fungal polyketides. (A) Combination of hrPKS and nrPKS. (B) Distinct hrPKSs. (C) hrPKS and NRPS. (D) hrPKS and terpene cyclase. (E) Collaboration of hrPKS and type Ⅲ PKS leading to the generation of soppillines in vivo, where PspA initiates and elongates the highly reducing polyketide chain, which is then transferred to PspB for additional extension, followed by 6e− oxidation by PspC. | |

Aside from the well-known collaborations of hrPKS with other skeleton core synthases, a new mode of partnership that hrPKS cooperating with the type Ⅲ PKS was recently discovered from fungus Penicillium soppi [27]. Heterologous expression of the psp cluster in Aspergillus oryzae in vivo demonstrated that it is responsible for the synthesis of alkylresorcinols soppilines A–C (Fig. 1E) [27]. In this process, hrPKS PspA and type Ⅲ PKS PspB work together first to form soppiline B, cytochrome P450 (CYP450) PspC subsequently catalyses a 6e− oxidation at C-4 of soppiline B to give soppiline C. However, it should be mentioning that the separate PspA yields soppiline A. A β–hydroxyl carboxylic acid indicating that, if the hrPK chain does not transfer into PspB, PspA likely carries out one more extension and reduction during the catalytic cycle. Therefore, although the bridge between psp cluster and soppilines has been established, the catalytic mechanism, collaborative manner, as well as the timing of the chain transfer between hrPKS and type Ⅲ PKS, remains unknown.

We identified three hrPKS and type Ⅲ PKS hybrid clusters from the genome database of Fusarium sp. in our lab (Fig. S3 in Supporting information), the representative fsc cluster from Fusarium scirpi CGMCC 3.3656 was shown in Fig. 2A (accession number OR551244). Since FscA and FscB showed 53% and 52% identities with PspA and PspB, respectively, strongly suggesting that the products of fsc cluster are also possible alkylresorcinol family compounds, although this type compounds catalysed by hrPKS and type Ⅲ PKS have not been identified from Fusarium sp. to date [28–30]. In contrast to psp cluster, the tailoring enzymes of fsc cluster are more abundant including a CYP450 FscC, a flavin-dependent halogenase FscD, and a methyltransferase FscE, which might install a variety of functional groups towards the putative alkylresorcinol backbone.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Confirmation of the function of fsc gene cluster. (A) Organization and proposed functions of genes in fsc cluster. (B) Overexpression of fscF resulted in the production of multi-substituted alkylresorcinols, and gene inactivation elucidated the function of each gene. (C) Compounds 1–7 were obtained from OE::fscF or mutant strains. | |

To identify the products of fsc cluster, especially clarifying the individual function of each gene, we first investigated the metabolite profiles of F. scirpi using various media. Unfortunately, F. scirpi could not produce any compounds containing the absorption features of alkylresorcinols under different culture conditions (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), which indicates that the fsc cluster is silent. Alternatively, we turned our attention to FscF, a Zn(Ⅱ)2Cys6 type transcriptional regulator, the family of which usually upregulates the expression of gene clusters [31,32]. When gene fscF was cloned under gpdA promoter (Supporting information), the resulting transformant Fs-OE::fscF was cultured on solid CYA medium and three major compounds scirpilins A-C (1–3) were detected by liquid chromatograph mass spectrometer (LC-MS) analysis (Fig. 2B, ⅰ, ⅱ, and Fig. S5 in Supporting information).

These three compounds were isolated from the large-scale cultivation and their structures were subsequently confirmed by high resolution mass spectrometry (HR-MS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analyses (Tables S4–S6 and S11, Figs. S17–S19 and S24–S42 in Supporting information). As shown in Fig. 2C, (1) compounds 1–3 all feature a resorcinol skeleton with a C20 alkyl side chain attached at C-1, where 1 is likely the precursor of 2 and 3; (2) the terminal carbons of alkyl chain in 2 and 3 are highly oxidized to form the rare succinic acid or malic acid moiety [33–35] (3) symmetrical di-methylation and di-halogenation are observed to occur on the resorcinol skeleton in 2 and 3. Further gene knock-out of fscA in Fs-OE::fscF, production of 1–3 were all abolished in Fs-OE::fscF∆fscA (Fig. 2B, ⅲ). These results fully confirmed that fsc cluster is responsible for the synthesis of 1–3 in F. scirpi, importantly showing Fusarium species fungi is also the dependable source for mining of alkylresorcinol type compounds. It is worth mentioning that the post-modification degrees from 1 to 2 and 3 indicating the all-tailoring enzymes (FscC–E) can work iteratively.

To investigate the collaborative manner of hrPKS FscA with type Ⅲ PKS FscB, these two genes were cloned and introduced into A. nidulans individually (Supporting information), where the transformant AN-fscA or AN-fscB did not produce any compounds (Fig. 3A, ⅰ–ⅲ). However, when fscA and fscB were co-expressed, the production of 1 was successfully detected by AN-fscAB (Fig. 3A, ⅳ). Subsequently, the conjoint role of FscA and FscB responsible for 1 formation was fully established by in vitro biochemical assays using purified enzymes (Fig. S8 in Supporting information). These results (1) showed the first biochemical evidence that a hrPKS and a type Ⅲ PKS can collaboratively synthesize alkylresorcinol family compound; (2) confirmed that both FscA and FscB are required to form 1, after the complete catalytic cycles of FscA, the following steps including chain transfer, extension and release might be accomplished by FscB. Different from the hrPKS-nrPKS mediated strategy (Fig. 1A), formation of alkylresorcinols via the manner of hrPKS-type Ⅲ PKS usually employs a decarboxylation step after cyclization and release of the polyketide chain (Figs. 3C and 1E) [17,36,37].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Characterization of the functions of FscA–FscE. (A) Heterologous expression of fscA and fscB in A. nidulans. (B) Heterologous expression of fscABC and CPR-Fs in A. nidulans. (C) The proposed pathway of 3 unveils a [7 + 3] collaborative model between FscA and FscB, and following iterative tailoring steps. (D) FscD catalyses the halogenation of 4. (E) FscE recognizes 6 to form di-methylated product 3. | |

Successful refactoring of the activity of FscA and FscB in vitro provides a good chance to clarify the catalytic mechanism of them, especial on the accurate timing of chain transfer from FscA to FscB. We proposed two possible routes for 1 synthesis by FscA and FscB (Fig. 3C): [7 + 3] or [8 + 2] mode, FscA carries out the first 7 or 8 cycles to yield the acyl carrier protein (ACP)-tethered polyketide chain, which is then transferred to FscB for 3 or 2 more cycles. To distinguish these two collaborative modes, we first chemically synthesized pyrene-Cys (Supporting information), which can nucleophilic attack the thioester using the sulfydryl group, followed by an intramolecular rearrangement to form a stable amide bond compound [38]. Therefore, pyrene-Cys could be used as an efficient hunter to capture the ACP-tethered polyketide intermediate [38]. After FscA-catalysed reaction, addition of pyrene-Cys captures the corresponding 7 cycle polyketide intermediate (Fig. S9 in Supporting information), which confirmed the catalytic program of FscA and showed the [7 + 3] mode should be the optimal route for 1 formation by FscA and FscB (Fig. 3C). Based on these results, the six carbon atoms of the resorcinol skeleton in 1–3, five carbons (C-2–C-6) are contributed by type Ⅲ PKS, while one carbon (C-1) is provided by hrPKS.

We next attempted to investigate the tailoring steps from 1 to 2 and 3, these transformation reactions are accomplished by the rest three enzymes, but at least installing six functional groups. Gene knock-out experiments confirmed that the production of 2 and 3 was indeed abolished by individual fscC, fscD and fscE mutant, however, as shown in Fig. 2B, ⅳ–ⅵ, (1) Fs-OE::fscF∆fscC accumulates 1; (2) Fs-OE::fscF∆fscD generates scirpilins D and E (4 and 5); and (3) Fs-OE::fscF∆fscE produces scirpilins F and G (6 and 7). Subsequent purification and structural determination showed that (1) 4 and 5 retain the terminal malic acid (or its methyl ester) moiety, while the symmetrical di-methylation and di-halogenation are absent (Fig. 2C, Tables S7, S8, and S11, Figs. S20, S21, and S43–S55 in Supporting information); (2) 6 and 7 are the di-halogenated products of 4 and 5 on resorcinol skeleton, respectively (Fig. 2C, Tables S9–S11, Figs. S22, S23, and S56–S68 in Supporting information).

Accumulation of 1 in Fs-OE::fscF∆fscC highly indicates that CYP450 FscC may catalyse the successive oxidation steps, towards the inert carbons (C-20, C-21, and C-22) of the terminal alkyl chain of 1, to form the rare malic acid moiety. In this process, FscC is likely responsible for the 14e− oxidation (two carboxylations and one hydroxylation, Fig. 3C). Therefore, FscC is a more multifunctional CYP450 for the oxidized modification of polyketide side chain of resorcinol family compounds relative to the homologue enzyme PspC that carries out 6e− oxidation for one carboxylation (Fig. 1E) [27,39].

To validate the function of FscC, we first constructed the bioconversion system by expressing fscC in A. nidulans (AN-fscC). However, when 1 was fed into AN-fscC, the expected corresponding product 4 was not detected (Fig. S10 in Supporting information). Considering the polarity feature of 1, we proposed that it might be difficult in penetrating the cell membrane to react with FscC. Therefore, we generate the AN-fscABC transformant, which could efficiently provide intracellular 1 in situ for FscC-catalysed oxidation. Unfortunately, except for 1, compound 4 has not been detected yet (Fig. 3B, ⅰ and ⅱ). This result highly indicated that the cytochrome P450 reductase (CPR) of A. nidulans might not support for the multistep oxidative function of FscC, thus the native CPR of F. scirpi should be essential for FscC.

Based on this hypothesis, we subsequently cloned the native CPR of F. scirpi (CPR-Fs) and combined it with fscABC to construct the AN-fscABC + CPR-Fs. As expected, the production of 4 was successfully detected (Fig. 3B, ⅱ and ⅳ). Elimination of fscC, the formation of 4 was also abolished (Fig. 3B, ⅲ). These results (1) established the iteratively oxidative function of FscC on catalysing 1 to form 4, which highlights an unexpected 14e− oxidation on three inert carbons by CYP450 to synthesize a rare malic acid functional group; (2) clarified the irreplaceable paring relationship of FscC with its native CPR-Fs, a representative example, which exhibits the CPR is also key for multifunctional CYP450s towards their catalytic roles [40,41].

We next investigated the last two steps in the formation of 2 and 3. These two steps are furnished by FscD and FscE, which catalyse iterative halogenation and methylation on resorcinol skeleton, respectively. Based on the gene knock-out results (Fig. 2B, ⅴ and ⅵ) as well as the electrophilic substitution mechanism of flavin-dependent halogenase, we proposed that the FscD-catalysed di-halogenation should occur prior to FscE-catalysed di-methylation [42–45]. To validate the function of FscD, the intron-free fscD was cloned, expressed, and purified from E. coli (Fig. S7 in Supporting information). With the assistance of flavin reductase (Fre) from the E. coli (Fig. S7), when 4 or 5 was incubated with FscD, the di-halogenated product 6 or 7 as well as the corresponding mono-halogenated intermediate 4a or 5a was successfully detected, respectively (Fig. 3D, Figs. S11, S13, and S14 in Supporting information). These biochemical results fully confirm the unusual function of FscD, it not only features an ability to use Cl− to attack Fl-C4a-OOH distal oxygen atom to generate Fl-C4a-OH and HClO, but also can iteratively use HClO as the electrophilic halogenation agent to install chlorine atoms at C-2 and C-6 of resorcinol skeleton (Fig. 3C). Therefore, FscD is a new resorcinol di-halogenase, it is distinguished from Rdc2 and RadH, a C-2 mono-halogenase in resorcinol radicicol biosynthesis (Fig. 1A) [15].

To investigate the final methylation step, FscE was also expressed and purified from E. coli (Fig. S7). As shown in Fig. 3E and Figs. S12 and S15 (Supporting information), when FscE was incubated with 6 or 7, product 3 or di-methylated 7a was effiently generated, respectively. These results confirm that FscE is indeed a iterative methytransferase, it is along with FscC and FscD, making an unexpected iterative tailoring assembly for the synthesis of multi-substituted alkylresorcinols.

In this work, we discovered a hybrid hrPKS and type Ⅲ PKS cluster in F. scirpi by genome mining, which leads to the discovery of three new multi-substituted alkylresorcinols (1–3). Biosynthesis of 1–3 represents an unexpected assembly machinery for resorcinol family compounds, mainly including (1) the hrPKS FscA and type Ⅲ PKS FscB collaborate in a [7 + 3] biosynthetic model to form the alkylresorcinol skeleton; (2) a 14e− oxidation is employed by a CYP450 FscC, converting the terminal of the alkyl chain to a rare malic acid moiety; (3) FscD and FscE iteratively catalyse symmetrical di-halogenation and di-methylation on the resorcinol moiety. Our study sets up the understanding of the collaboration mechanism between hrPKS and type Ⅲ PKS in polyketide synthesis and expands the arsenal of three iterative enzymes (CYP450, halogenase and methytransferase) for the tailoring of alkylresorcinol family natural products in future.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22277100), the National Key R&D Program of China (No. 2020YFA0907700), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Nos. SWU-KQ22034 and SWU-XDPY22009), the Science and Technology Innovation Key R&D Program of Chongqing (No. CSTB2022TIAD-STX0015), and the Chongqing Science Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (No. cstc2020jcyj-jqX0005).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108968.

| [1] |

X. Hu, X. Li, S. Yang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107516. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.05.030 |

| [2] |

Q. Li, M. Zhang, X. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108193. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108193 |

| [3] |

X. Peng, J. Chang, Y. Gao, F. Duan, H. Ruan, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4572-4576. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.063 |

| [4] |

H. Ran, S. Li, Nat. Prod. Rep. 38 (2021) 240-263. DOI:10.1039/D0NP00026D |

| [5] |

A.R. Carroll, B.R. Copp, R.A. Davis, R.A. Keyzers, M.R. Prinsep, Nat. Prod. Rep. 39 (2022) 1122-1171. DOI:10.1039/D1NP00076D |

| [6] |

R.J. Cox, Nat. Prod. Rep. 40 (2023) 9-27. DOI:10.1039/D2NP00007E |

| [7] |

D. Boettger, C. Hertweck, ChemBioChem 14 (2013) 28-42. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201200624 |

| [8] |

N. Tibrewal, Y. Tang, Annu. Rev. Chem. Biomol. Eng. 5 (2014) 347-366. DOI:10.1146/annurev-chembioeng-060713-040008 |

| [9] |

S. Gao, A. Duan, W. Xu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 4249-4259. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b01528 |

| [10] |

M. Sato, S. Kishimoto, M. Yokoyama, et al., Nat. Catal. 4 (2021) 223-232. DOI:10.1038/s41929-021-00577-2 |

| [11] |

K.E. Lebe, R.J. Cox, Chem. Sci. 10 (2019) 1227-1231. DOI:10.1039/C8SC02615G |

| [12] |

X. Mao, Z. Zhan, M.N. Grayson, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 11904-11907. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b07816 |

| [13] |

S. Gao, T. Zhang, M.G. Borràs, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 6991-6997. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b03705 |

| [14] |

R. Fasan, ACS Catal. 2 (2012) 647-666. DOI:10.1021/cs300001x |

| [15] |

S. Wang, Y. Xu, E.A. Maine, et al., Chem. Biol. 15 (2008) 1328-1338. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.10.006 |

| [16] |

Y. Chiang, E. Szewczyk, A.D. Davidson, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 2965-2970. DOI:10.1021/ja8088185 |

| [17] |

X. Wang, C. Wang, L. Duan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 4355-4364. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b12967 |

| [18] |

J.M. Winter, M. Sato, S. Sugimoto, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134 (2012) 17900-17903. DOI:10.1021/ja3090498 |

| [19] |

J. Kennedy, K. Auclair, S.G. Kendrew, et al., Science 284 (1999) 1368-1372. DOI:10.1126/science.284.5418.1368 |

| [20] |

W. Wang, H. Wang, L. Du, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 8464-8472. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c02337 |

| [21] |

S.M. Ma, J.W.H. Li, J.W. Choi, et al., Science 326 (2009) 589-592. DOI:10.1126/science.1175602 |

| [22] |

J. Zhang, H. Wang, X. Liu, C. Hu, Y. Zou, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 1957-1965. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b11410 |

| [23] |

N. Kato, T. Nogawa, R. Takita, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 9754-9758. DOI:10.1002/anie.201805050 |

| [24] |

M. Ohashi, T.B. Kakule, M. Tang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 5605-5609. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c00098 |

| [25] |

H. Lin, Y.H. Chooi, S. Dhingra, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 4616-4619. DOI:10.1021/ja312503y |

| [26] |

Y. Huang, S. Hoefgen, V. Valiante, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 23763-23770. DOI:10.1002/anie.202108970 |

| [27] |

A. Kaneko, Y. Morishita, K. Tsukada, T. Taniguchi, T. Asai, Org. Biomol. Chem. 17 (2019) 5239-5243. DOI:10.1039/C9OB00807A |

| [28] |

A.M. Ahmed, B.K. Mahmoud, N.M. Aguiñaga, U.R. Abdelmohsen, M.A. Fouad, RSC Adv. 13 (2023) 1339-1369. DOI:10.1039/D2RA04126J |

| [29] |

R. Gerber, L. Lou, L. Du, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 (2009) 3148-3149. DOI:10.1021/ja8091054 |

| [30] |

H. Morita, C.P. Wong, I. Abe, J. Biol. Chem. 294 (2019) 15121-15136. DOI:10.1074/jbc.REV119.006129 |

| [31] |

P. Wang, J. Xu, P.K. Chang, Z. Liu, Q. Kong, Microbiol. Spectr. 10 (2022) e00791-21. |

| [32] |

N.P. Keller, Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 17 (2019) 167-180. DOI:10.1038/s41579-018-0121-1 |

| [33] |

N. Liu, Y.S. Hung, S. Gao, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 3560-3563. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01534 |

| [34] |

B. Dose, C. Ross, S.P. Niehs, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 21535-21540. DOI:10.1002/anie.202009107 |

| [35] |

Y. Dashti, I.T. Nakou, A.J. Mullins, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 21553-21561. DOI:10.1002/anie.202009110 |

| [36] |

H. Zhou, K. Qiao, Z. Gao, J.C. Vederas, Y. Tang, J. Biol. Chem. 285 (2010) 41412-41421. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M110.183574 |

| [37] |

Y. Xu, T. Zhou, Z. Zhou, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110 (2013) 5398-5403. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1301201110 |

| [38] |

L.A. Washburn, K.K. Nepal, C.M.H. Watanabe, ACS Chem. Biol. 16 (2021) 1737-1744. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.1c00437 |

| [39] |

Y. Iizaka, D.H. Sherman, Y. Anzai, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 105 (2021) 2647-2661. DOI:10.1007/s00253-021-11216-y |

| [40] |

S. Li, L. Du, R. Bernhardt, Trends Microbiol. 28 (2020) 445-454. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2020.02.012 |

| [41] |

X. Zhang, J. Guo, F. Cheng, S. Li, Nat. Prod. Rep. 38 (2021) 1072-1099. DOI:10.1039/D1NP00004G |

| [42] |

V. Agarwal, Z.D. Miles, J.M. Winter, et al., Chem. Rev. 117 (2017) 5619-5674. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00571 |

| [43] |

C. Crowe, S. Molyneux, S.V. Sharma, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 50 (2021) 9443-9481. DOI:10.1039/D0CS01551B |

| [44] |

A.E. Fraley, D.H. Sherman, Bio. Med. Chem. Lett. 28 (2018) 1992-1999. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2018.04.066 |

| [45] |

R.D. Barker, Y. Yu, L.D. Maria, L.O. Johannissen, N.S. Scrutton, ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 15352-15360. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c05231 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35