b Key Laboratory for Marine Drugs and Bioproducts, Laoshan Laboratory, Qingdao 266237, China;

c School of Biological Science and Technology, University of Jinan, Ji'nan 250022, China;

d Key Laboratory for Biosensors of Shandong Province, Biology Institute, Qilu University of Technology, Ji'nan 250103, China

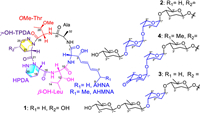

Over 120 cyclopeptides that contain hexahydropyridazine-3-carboxylic acid (HPDA) have been reported [1], including piperazimycin A [2], hytramycin V [3], and soliseptide A [4]. These molecules, in general, show strong bioactivities, including cytotoxic, antimicrobial and antiviral activities [1]. The cytotoxic and antibacterial activities of 7-O-L-rhodosamine- or rhodinose-bearing anthracyclines significantly increased compared to the aglycone [5,6], indicating that bioactivity of the aglycone could be improved by glycosylation. Our group has isolated five HPDA-containing cyclohexapeptides, pyridapeptides A–E, from the marine sponge-derived Streptomyces strain OUCMDZ-4539, among which pyridapeptides B–E bearing one or more 2,3,6-trideoxyhexose residues displayed significant antiproliferative activity [7]. These reports indicated that oligosaccharide chains were important for antiproliferative activity. To obtain diverse pyridapeptide analogs containing sugar lotus, we re-fermented the strain OUCMDZ-4539 in a large amount of liquid media and examined various secondary metabolites. As a result, we identified four new cyclohexapeptides, pyridapeptides F–I (1–4) (Fig. 1).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Structures of compounds 1–4. | |

Pyridapeptide F (1) was obtained as a white solid. The molecular formula was determined to be C33H52O10N8 with an index of hydrogen deficiency (IHD) of 11 from the high resolution electrospray ionization mass spectroscopy (HRESIMS) peak at m/z 719.3715 [M−H]− (calcd. 719.3734) (Fig. S15 in Supporting information). The relationships between the specific proton and carbon signals in the 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data of compound 1 were established by the heteronuclear singular quantum correlation (HSQC) spectrum. Six downfield carbon signals for the amide or ester carbonyl groups at δC 169.6, 169.7, 170.0, 171.0, 171.2, and 171.3 as well as six α-amino acid methine carbons at δC 48.3, 49.5, 50.0, 53.4, 55.9, and 56.1 were observed in the 13C NMR spectrum. Meanwhile, four amide proton signals at δH 8.40, 8.31, 8.06, and 7.59 were observed in the 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1), revealing that 1 should be a hexapeptide.

|

|

Table 1 1H (500 MHz) and 13C (150 MHz) NMR data for pyridapeptide F (1) in DMSO–d6. |

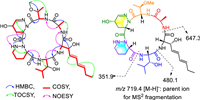

Analyses of the 1H–1H correlation spectroscopy (COSY) and heteronuclear multiple bond correlation (HMBC) spectra revealed six partial structures, as shown in Fig. 2. The 1H–1H COSY and total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) correlations of HN-2 (δH 8.06)/H-2/H-3/H-4/H-5/H-6/H-7/H2-8/H3-9 and the HMBC correlations of the α-methine H-2 (δH 4.42) to C-1 (δC 169.6) showed the presence of the 2-amino-3-hydroxynona-4,6-dienoic acid (AHNA) residue. The 1H–1H COSY and TOCSY correlations of HN-11 (δH 8.31)/H-11/H-12/H-13/H3-14 (H3-15) and the HMBC correlations of the α-methine H-11 (δH 4.24) to C-10 (δC 170.0) showed the presence of a β-hydroxyleucine (β-OH-Leu) moiety. The proximity of the α-methine H-17 (δH 4.80) to HN-20 (δH 5.14) through H2-18 (δH 1.75/2.04), H2-19 (δH 1.47), and H2-20 (δH 2.65/3.07) in the COSY and the correlations of H-17 (δH 4.80) to C-16 (δC 171.0) in the HMBC suggested the presence of an HPDA residue. The 1H–1H COSY spin system from the α-methine H-22 (δH 5.72) to H-25 (δH 6.83) and the HMBC from H-22 to C-21 (δC 171.3) together with the chemical shifts of CH-24 (δH/C 4.00/59.0) and CH-25 (δH/C 6.83/146.9) suggested the presence of a 5-hydroxytetrahydropyridazine-3-carboxylic acid (γ-OH-TPDA) residue. The 1H–1H COSY and TOCSY correlations of HN-27 (δH 7.59)/H-27/H-28/H3–29 and the HMBC correlations of the α-methine H-27 (δH 5.17) to C-26 (δC 169.7) and 28-OCH3 (δH 3.16) to C-28 (δC 76.7) showed the presence of an O-methylthreonine (OMe-Thr) moiety. The 1H–1H COSY correlations of 31-NH (δH 8.40)/H-31/H3-32 and the HMBC correlations of H-31/H3-32 to C-30 (δC 171.2) indicated the presence of an alanine (Ala) moiety. The connectivity among these residues was established, as showing in Fig. 2, by the key HMBC correlations from H-2 of AHNA to C-10 of β-OH-Leu, HN-11 of β-OH-Leu-to C-16 of HPDA, HN-20 of HPDA to C-21 of γ-OH-TPDA, and HN-31 of Ala to C-1 of AHNA as well as the key NOESY correlations between HN-2 of AHNA and H-11 of β-OH-Leu, HN-11 of β-OH-Leu and H-17 of HPDA, HN-20 of HPDA and H-22 of γ-OH-TPDA, HN-27 of OMe-Thr and H-31 (δH 4.27) of Ala, HN-31 of Ala and H-2 of AHNA. These results revealed that compound 1 was an undocumented cyclohexapeptide, namely cyclo-(AHNA-(β-OH-Leu)-HPDA-(γ-OH-TPDA)-(OMe-Thr)-Ala). The suggested sequence was further confirmed by the positive ESI-MS2 fragment ion series at m/z 719.4, 647.3, 480.1 and 351.9 [M−H]– corresponding to the parent and fragment ions by the loss of Ala, AHNA, and β-OH-Leu in turn. Both Δ4 and Δ6 double-bond geometries of the AHNA residue were assigned as E- by 15.0 Hz and 15.2 Hz of the 3J coupling constants.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Key 2D NMR correlations and MS2 fragmentation of 1. | |

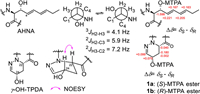

The absolute configuration of compound 1 was determined as follows, among which the Ala, OMe-Thr, HPDA and β-OH-Leu residues of 1 were found by the advanced Marfey's method using L- and D-N-(5-fluoro-2,4-dinitrophenyl)valinamide (FDVA) [8,9]. The results indicated that compound 1 contained D-Ala, L-HPDA (Fig. S2 in Supporting information), (R)-OMe-L-Thr and (3R)-OH-L-Leu (Fig. S3 in Supporting information). The cis- configuration of γ-OH-TPDA was assigned according to the nuclear overhauser effect spectroscopy (NOESY) correlation of H-22 and H-24 and was further determined to be (S,S)- after elucidating 24-OH as the S- configuration by Mosher's method (Fig. 3). The configuration of AHNA was elucidated as threo– by the heteronuclear single quantum multiple bond correlation (HSQMBC) spectrum [10] that gave3JH2-H3, 2JH2-C3 and 2JH3-C2 values of 4.1, 5.9 and 7.2 Hz, and further determined as having an (S,R)- configuration by Mosher's method (Fig. 3) [7].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Configurations of AHNA and γ-OH-TPDA units of 1. | |

Both pyridapeptides G (2) and H (3) provided compound 1 following mild hydrolysis with 0.5 mol/L HCl under an argon atmosphere (Fig. S4 in Supporting information), indicating that they shared the same pyridapeptide F (1) backbone. The molecular formula of pyridapeptide G (2) was determined to be C57H92O18N8 by HRESIMS at m/z 1175.6455 [M–H]− (calcd. 1175.6446) (Fig. S33 in Supporting information), with a molecular weight of 114 × 4 amu higher than that of pyridapeptide F (1), implying four extra trideoxyhexose residues. Apart from the NMR signals for cyclic hexapeptide (1), the 1H and 13C NMR data of compound 2 (Table S2 in Supporting information) contained 24 extra carbon signals that were classified by the HSQC spectrum as four acetal methines (δC/H 100.5/4.75, CH-1′; δC/H 98.2/4.79, CH-1′′; δC/H 98.6/4.69, CH-1′′′; δC/H 103.0/4.39, CH-1′′′′), eight oxymethines (δC/H 78.1/3.06, CH-4′; 73.9/3.38, CH-5′; δC/H 74.8/3.44, CH-4′′; 66.2/3.81, CH-5′′; δC/H 66.2/3.38, CH-4′′′; 66.7/3.80, CH-5′′′; δC/H 75.5/3.11, CH-4′′′′; 70.0/4.33, CH-5′′′′), eight methylenes (δC/H 30.4/1.83&1.40, CH2–2′; 29.1/1.98&1.52, CH2–3′; δC/H 30.7/1.82 &1.40, CH2–2′′; 24.1/1.78&1.48, CH2–3′′; δC/H 24.0/1.80&1.40, CH2–2′′′; 24.4/1.83&1.40, CH2–3′′′; δC/H 24.6/1.80&1.38, CH2–2′′′′; 31.1/1.81&1.31, CH2–3′′′′), and four methyls (δC/H 17.0/1.12, CH3–6′; δC/H 18.2/1.10, CH3–6′′; δC/H 17.0/0.96, CH3–6′′′; δC/H 18.4/0.99, CH3–6′′′′). In addition, the 1H–1H COSY spectrum displayed correlations from H-1′ to H-6′, H-1′′ to H-6′′, H-1′′′ to H-6′′′ and H-1′′′′ to H-6′′′′ in sequence. These data presented the four trideoxyhexose residues as the 2,3,6-trideoxyhexoses, implying that compound 2 was a tetraglycoside of pyridapeptide F (1) and further confirmed by MS2 analysis (Fig. S44 in Supporting information). The NOESY correlations (Fig. S9 in Supporting information) of H-1′ (δH 4.75) with H-5′ (δH 3.38), H-4′′ (δH 3.44) with H3–6′′ (δH 1.10), H-4′′′ (δH 3.38) with H3–6′′′ (δH 0.96) and H-1′′′′ (δH 4.40) with H-5′′′′ (δH 4.33) respectively suggested the trans-H-1′/H3–6′, cis-H-4′′/H3–6′′, cis-H-4′′′/H3–6′′′, and trans-H-1′′′′/H3–6′′′′ orientations, indicating that these 2,3,6-trideoxyhexoses could be amicetose, rhodinose, rhodinose and amicetose in sequence. This deduction was then confirmed by the complete hydrolysis of compound 2 in 2 mol/L HCl at 90 ℃ followed by hydrazonation with 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine that yielded equal amounts of D-amicetose-2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (6) and L-rhodinose-2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (7), both detected at m/z 311 [M−H]– (Figs. S7 and S8 in Supporting information), as identified by NMR (Table S2), LC-MS (Fig. S6 in Supporting information) and specific rotation ([α]D20 −9.2 vs. −10.0 (c 0.15, pyridine) for 6 and −21.5 vs. −21.4 (c 0.14, pyridine) for 7) [7]. Furthermore, the NOESY correlation from the anomeric proton H-1′′ (δH 4.79) to H-4′ (δH 3.06), H-1′′′ (δH 4.69) to H-4′′ (δH 3.44), and H-1′′′′ (δH 4.39) to H-4′′′ (δH 3.38) completed the connectivity of these monosaccharides linked into a tetrasaccharide by three 1,4-glycosidic bonds. The key NOESY correlation of the anomeric proton H-1′ (δH 4.75) with H-24 (δH 4.11) of the γ-OH-TPDA residue, as well as the values of δC-24 and δC-25 of compound 2 that were respectively 7.0 ppm increase and 3.8 ppm decrease when compared to compound 1, indicated that the glycosidation occurred at 24-OH of the cyclic hexapeptide. The 1JC-H values for CH-1′, 1′′, 1′′′, and 1′′′′ were respectively measured as 153, 170, 165 and 152 Hz (Fig. S43 in Supporting information), suggesting the axial orientations for both H-1′ and H-1′′′′, and equatorial orientations for both H-1′′ and H-1′′′ [7]. That is β-anomer for both D-amicetoses and α-anomer for both L-rhodinoses. Consequently, pyridapeptide G (2) was elucidated as 24-O-(β-D-amicetopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhodinopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhodinopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-amicetopyranosyl) pyridapeptide F.

Pyridapeptide H (3) was an isomer of 2 based on the same molecular formula from the HRESIMS peak at m/z 1175.6404 [M–H]− (calcd. 1175.6446) (Fig. S45 in Supporting information) and MS2 analysis (Fig. S56 in Supporting information). Comparison of the 1H, 13C NMR (Table S3 in Supporting information), and NOESY (Fig. S9) spectra of 3 with those of 2 revealed a difference in that an amicetose residue in 3 replaced the corresponding rhodinose residue in 2. The same thermal acidolysis of 3 followed by a similar hydrazonation as for 2 yielded a 3:1 ratio of compounds 6 and 7 (Figs. S7 and S8) and specific rotations, further confirming this deduction. The NOESY correlations of H-1′′′ (δH 4.46) to H-4″ (δH 3.45) and H-5′″ (δH 3.10) (Fig. S9) suggested that the third hexose residue of 2, L-rhodinose, was replaced by the D-amicetose in 3. The 155 Hz of 1JC-H value for CH-1′′′ suggested a β-anomeric center (Fig. S55 in Supporting information). Thus, pyridapeptide H (3) was elucidated as 24-O-(β-D-amicetopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-amicetopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhodinopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-amicetopyranosyl) pyridapeptide F.

Pyridapeptide Ⅰ (4) provided pyridapeptide A (5) (Fig. S10 in Supporting information) following mild hydrolysis with 0.5 mol/L HCl under an argon atmosphere (Fig. S3), indicating that they shared the same cyclohexapeptide backbone [7]. The molecular formula of 4 was determined to be C52H80O16N8 based on the HRESIMS at m/z 1071.5588 [M–H]− (calcd. 1071.5614) (Fig. S57 in Supporting information) with 110 amu higher than pyridapeptide C, a new bioside [7]. The NMR data (Table S4 in Supporting information) of compound 4 exhibited a high degree of similarity to that of pyridapeptide C [7], supporting a 2-amino-3–hydroxy-8-methylnona-4,6-dienoic acid (AHMNA) residue in compound 4. A thorough analysis of 1D NMR and examining the NOESY of 4 (Fig. S9) revealed an additional six-carbon fragment than pyridapeptide C. This fragment contained by the HSQC spectrum an acetal methine (δC/H 94.7/5.33, CH-1′′′), two olefinic methines (δC/H 145.0/7.07, CH-2′′′; δC/H 126.2/6.08, CH-3′′′), a carbonyl (δC 196.9, CH-4′′′), an oxymethine (δC/H 69.7/4.51, CH-5′′′), and a methyl group (δC/H 15.2/1.23, CH3–6′′′). This additional sugar moiety was further determined as an aculose residue according to the 1H–1H COSY correlations from H-1′′′ to H-3′′′ via H-2′′′ as well as the NOESY correlation of H-3′′′ (δH 6.08) with H-5′′′ (δH 4.51) (Fig. S9). And the small coupling constant of H-1′″ (3.5 Hz) was consistent with the α-anomer [11]. The same thermal acidic hydrolysis of 4 followed by a similar hydrazonation as for 1 yielded a 1:1 ratio of compounds 6 and 7 (Fig. S6). Consequently, pyridapeptide I (4) was elucidated as 4′′-O-α-L-aculosylpyridapeptide C after combination of the MS2 analysis (Fig. S68 in Supporting information).

Compounds 1–4 were evaluated for their antiproliferative activity against PC9, MKN45, HepG2, K562, L-02 cell lines by the cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay [12,13] using adriamycin as the positive control. The results (Table S5 in Supporting information) showed that compounds 2 and 3 bearing linear tetrasaccharide chains exhibited a broad-spectrum of antiproliferative activity against the five human cell lines with the values of 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) ranging from 1.33 µmol/L to 3.33 µmol/L, while compound 4 having a trisaccharide chain showed a selective antiproliferation against the human lung cancer cell line (PC9) and human hepatoma cell line (HepG2) with IC50 value of 3.39 µmol/L and 3.04 µmol/L, respectively. Cyclohexapeptide (1) was no significant activity against the proliferation of the five cell lines (IC50 > 10 µmol/L). These data combined with our published results [7] indicated that the linear tetraglycosides, compounds 2 and 3 as well as pyridapeptides D and E (Fig. S10), all showed a broad-spectrum of antiproliferative activity against all the tested human cells, while the diglycoside, pyridapeptide C, and the linear triglycoside 4 displayed a selective antiproliferation against one or two human tumor cells. However, the aglycone, compound 1 and pyridapeptide A as well as the monoglycoside, pyridapeptide B (Fig. S10), did not show bioactivity against the proliferation of the cell lines (IC50 > 10 µmol/L), indicating that the oligosaccharide modification significantly increases the antiproliferation of these cyclohexapeptides. Our results again confirmed that marine-derived microorganisms are an important source of bioactive natural products [14,15].

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. U1906213) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2022YFC2804100).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108950.

| [1] |

K.D. Morgan, R.J. Andersen, K.S. Ryan, Nat. Prod. Rep. 36 (2019) 1628-1653. DOI:10.1039/C8NP00076J |

| [2] |

E.D. Miller, C.A. Kauffman, P.R. Jensen, W. Fenical, J. Org. Chem. 72 (2007) 323-330. DOI:10.1021/jo061064g |

| [3] |

G. Cai, J.G. Napolitano, J.B. Mcalpine, et al., J. Nat. Prod. 76 (2013) 2009-2018. DOI:10.1021/np400145u |

| [4] |

J. Wang, Z. Cong, X. Huang, et al., Org. Lett. 20 (2018) 1371-1374. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00142 |

| [5] |

C. Gui, J. Yuan, X. Mo, et al., J. Nat. Prod. 81 (2018) 1278-1289. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.8b00212 |

| [6] |

C. Cui, J. Chen, Q. Xie, et al., J. Commun. Biol. 2 (2019) 454. DOI:10.1038/s42003-019-0699-5 |

| [7] |

S. Zhao, Y. Xia, H. Liu, et al., Org. Lett. 24 (2022) 6750-6754. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02520 |

| [8] |

P. Fu, M. Jamison, S. La, J.B. MacMillan, Org. Lett. 16 (2014) 5656-5659. DOI:10.1021/ol502731p |

| [9] |

H. Zhou, Y.B. Yang, R.T. Duan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 27 (2016) 1044-1047. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.03.018 |

| [10] |

N. Matsumori, D. Kaneno, M. Murata, H. Nakamura, K. Tachibana, J. Org. Chem. 64 (1999) 866-876. DOI:10.1021/jo981810k |

| [11] |

I. Voitsekhovskaia, C. Paulus, C. Dahlem, et al., Microorganisms 8 (2020) 680. DOI:10.3390/microorganisms8050680 |

| [12] |

M. Lan, T. Cui, K. Xia, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 508-510. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.05.028 |

| [13] |

H. Chen, F. Xu, B.B. Xu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 27 (2016) 277-282. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.09.016 |

| [14] |

C.L. Xie, D. Zhang, K.Q. Guo, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2057-2059. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.073 |

| [15] |

F. Li, W. Sun, S. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 197-201. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.04.036 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35