b State Key Laboratory of Bioactive Substance and Function of Natural Medicines, Beijing Key Laboratory of New Drug Mechanisms and Pharmacological Evaluation Study (BZ0150), Institute of Materia Medica, Peking Union Medical College and Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing 100050, China;

c The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, Wenzhou 325000, China

Drugs usually exert biological activities by virtue of covalent or non-covalent interactions with their targets. Compared with non-covalent drugs, most covalent drugs have pharmacological advantages including longer action time and stronger efficacy [1,2], which makes the drug development in recent years intentionally introduce electrophilic warheads that can covalently interact with targets [3,4]. The covalent interaction between the electrophilic warheads and nucleophilic amino acids is the basis of mode of action for covalent drugs [5–7]. There are usually three approaches designing the covalent drugs or probes. The first approach is to add an electrophilic warhead to known non-covalent inhibitors. An exemplary example is Ibrutinib that is an irreversible drug to inhibit bruton's tyrosine kinase (BTK) and treats different types of cancers including chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma [8]. The success of ibrutinib derivated from the equipment of various electrophilic warheads into a non-covalent compound [9]. The second one is to discover potent covalent inhibitor in a fragment-based manner. This approach attracts intense research interest and it can be used in the basis of pure protein [10–12] or whole cellular proteome [13]. A recent impressive study via fragment-based screening identified potent electrophilic fragment of main protease of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) [14]. The third approach is by virtue of phenotypic screening of a library of covalent bioactive compounds originating from both natural products [15] or synthetic molecules [16,17]. In this approach, the protein target of a covalent bioactive compound is unknown in advance. Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) [18–23] or other methods of chemical proteomics [24,25] are usually employed to identify the protein targets of these bioactive compounds. Though these above-mentioned three approaches have their own features, they all heavily rely on electrophilic warheads that thereby attract intense research efforts. Most of electrophilic warheads are Michael acceptors, such as acrylamide (osimertinib) [26], vinylsulfonamide [27], and alkynyl amide [22] or substituted alkynyl amide [18] (acalabrutinib). Halomethyl group activated by carbonyl group [28] or other electron-deficient groups [29,30] were also widely used as the electrophilic warheads. Interestingly, α-chlorofluoroacetamide (CFA) was a novel class of warhead that formed a covalent and reversible bond with targeted cysteine [31]. Sulfur(Ⅵ) fluorides including arylsulfonyl fluorides (Ar-SO2F) and arylfluorosulfates (Ar-OSO2F) are relatively weak electrophiles targeting lysine via SuFEx-based chemistry [27,32,33]. The reason why so many electrophilic warheads are developed is that different warheads will facilitate the design of covalent inhibitors with desired reactivity and target selectivity. Thereby, electrophilic warheads with tunable reactivity and selectivity are highly demanded in various research fields including medicinal chemistry and chemical biology.

The pharmacophore, 1,2,4-triazole, is a common framework in the field of drug research and development [34]. This pharmacophore is often found in various clinical drugs, such as voriconazole [35] and itraconazole [36]. The thiol-substituted 1,2,4-triazole group has been widely studied in the field of medicinal chemistry [37,38]. Herein, we show that thiol-substituted 1,2,4-triazole group is an excellent group to activate the chloromethyl electrophilic warhead. Notably, separable regioisomers of 1,2,4-triazole was pairwise-obtained, being different from the previous reports that the electrophilic warheads are singly obtained (Fig. 1A). The covalent-working mechanism of this new warhead was verified by various approaches of chemical proteomics. A small-scale compound library of pairs of regioisomers was constructed to examine the reactivity and selectivity of this new warhead. At last, the modes of cell death induced by a pair of regioisomers with specific labeling pattern in the whole were explored.

|

Download:

|

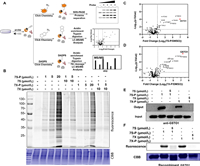

| Fig. 1. (A) The structure of pairwise-obtained new electrophilic warhead. (B) Design and synthesis of fully-functionalized isomeric covalent probes. (a) N2H4·H2O, EtOH, reflux; (b) 3-pyridyl isothiocyanate, EtOH, reflux; (c) 1 mol/L NaOH, reflux; (d) 6–chloro-1-hexyne, K2CO3, DMF, r.t.; (e) 1.0 mol/L BCl3, CH2Cl2, 0–5 ℃; (f) SOCl2, CH2Cl2, 0–5 ℃. (C) Viability of HCT116 cells upon incubation with 6S-P, 7S-P and 7S for 72 h. (D) Viability of HCT116 cells upon incubation with 6X-P, 7X-P and 7X for 72 h. Values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3 in each group). | |

The new electrophilic inhibitor based on thiol-substituted 1,2,4-triazole group was initially designed as 7X-P (Fig. 1B). The chloromethyl group activated by thiol-substituted 1,2,4-triazole group could potentially serve as a covalent group to irreversibly react with protein target. The substitution of 3-pyridine was initially selected because of two reasons. First, we intended introduce an aromatic ring at the 3 position. Second, this substitute was introduced at the second step and the corresponding material 3-pyridyl isothiocyanate is commercially accessible. Its alkyne group could be catalyzed via copper(Ⅰ) to react with the fluorophore-/biotin-modified azide (CuAAC) and thereby evaluate whether the new compound could covalently modify proteins. Following the designed synthetic scheme, we surprisingly obtained two regioisomers at the fourth step using DMF as the solvent and K2CO3 as the base. Interestingly, only S-substituted products was obtained when alcohol solvent, heat, or stronger base was employed, which was consistent with previous reports [39]. These results implied that the choice of reaction solvent and base played an important role in the generation of regioisomers. This is a rare example that the alkylation could simultaneously generate these two separable regioisomers of 1,2,4-triazole [40–46]. Notably, Although previous report concluded that the formation of S-alkyl derivatives as a sole product when using DMF as the solvent [39], we did obtain the S-alkyl derivative as main product and N-alkyl derivative as the minor product. We believe that the substitutes of thiol-substituted 1,2,4-triazole affects the tautomerism so that we could get the two regioisomers. The two isomers were further treated with BCl3 and SOCl2 successively to give the two final products, 7X-P and its regioisomer 7S-P. Two control products (7X and 7S) without an alkyne group were also synthesized. Their chemical structures were confirmed to be correct via high resolution mass spectrometer (HRMS) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Supporting information). 7X-P, 7S-P, 7X and 7S showed moderate cytotoxicity towards HCT116 cells, while their precursors (6X-P and 6S-P) did not show any inhibitory effect (Figs. 1C and D). This result indicated that the covalent function of chloromethyl group in 7X-P/7X and 7S-P/7S played an important role in their biological effects.

We next applied experiments of activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) to study the mode of action of two isomeric covalent probes (Fig. 2A). This ABPP study included three experiments consisting of fluorescence scanning, target identification and binding site mapping. First, we treated live HCT116 cells with isomeric probes for 1 h, followed by lysis and click reaction with rhodamine-azide. Upon sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and in-gel fluorescence scanning of the labeled proteomes, a selectively labeled band between 25 and 35 kDa emerged (Fig. 2B). The fluorescence intensity of this band was dependent on the concentration of the probes, and was remarkably competed by excessive 7S and 7X without the alkyne group (Fig. 2B). Second, we treated the probe-labeled proteome with a biotin-azide reporter via CuAAC, followed by affinity enrichment and label-free quantification (LFQ). LFQ proteomics result as well as the following original data used to identify protein targets and binding sites can be found in Supporting information. By comparing the fold changes between the probe-captured and vehicle-captured proteomes, we found that the glutathione S-transferase omega 1 (GSTO1) showed the largest value of fold change amongst all identified proteins (Figs. 2C and D). The molecular weight of GSTO1 was 27.5 kDa, which was consistent with migration position (25–35 kDa) in the SDS-PAGE/in-gel fluorescence scanning. Furthermore, the results of Western blot (WB) revealed that GSTO1 was indeed pulled down by 7S-P or 7X-P in HCT116 cells and the binding of 7S-P and 7X-P to GSTO1 was blocked by preincubating the proteome with 7S and 7X (Fig. 2E). A similar labeling pattern was also observed as for the pure recombinant GSTO1 enzyme (Fig. 2F). In addition, 7S-P and 7X-P could potently inhibit the activity of GSTO1 with an half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 3.88 and 4.58 µmol/L (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). Together, these data indicated that GSTO1 is a direct target of 7S-P and 7X-P in HCT116 cells.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Target identification and validation of isomeric covalent probes. (A) Schematic workflow of chemical proteomic platform to profile protein targets labelled by the isomeric probes in situ. (B) In situ concentration-dependent ABPP labeling of HCT116 cells with isomeric probes. CBB, Coomassie brilliant blue. (C, D) Volcano plot of label-free quantitative LC-MS experiments of proteomes labeled with 7S-P and 7X-P (1 µmol/L) or DMSO (negative control). (E) Competitive labeling of GSTO1 by isomeric probes with 7S or 7X. The labeled proteomes were "clicked" with biotin reporter ('input'), pulled down by avidin beads and eluted by boiling the beads ('output'). The input and output samples were analyzed by anti-GSTO1 immunoblotting. (F) The competitive labeling of recombinant GSTO1 by isomeric probes with 7S or 7X. | |

We subsequently analyzed the direct binding site of 7S-P and 7X-P at both levels of complicated whole proteome (DADPS) [47] to profile the binding sites of studied probes in live cells (Fig. 3A). Following the similar method as label-free quantification (Fig. 2A), we collected the peptides containing the binding information by treating the enriched avidin beads with trypsin and formic acid. The tandem MS/MS analysis of modified peptides indicated that 7S-P and 7X-P could label Cys32 of GSTO1 (Figs. 3B and C). To verify this binding information from whole proteome, we next carried out liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of peptides generated by tryptic digestion of probe-treated recombinant pure GSTO1 (Fig. 3D). Being different from the result of whole live cells, three cysteine sites (Cys32, Cys112 and Cys192) were identified in the level of the recombinant protein (Figs. 3E and F and Figs. S2–S4 in Supporting information). To understand the difference between these two methods, we subsequently carried out two confirmatory experiments. First, we carried out the labeling experiment using mutant GSTO1. We prepared recombinant mutant versions of GSTO1 (C32A, C90A, C112A and C192A) by site-directed mutagenesis. The C90A mutant protein served as a negative control. The mutant proteins were treated with 7S-P and 7X-P, followed by click chemistry and fluorescence scanning. As shown in Fig. 3G, the C32A mutagenesis almost abolished the labeling between probes and pure protein while other mutants could be still strongly labeled by the probes. This result thereby indicated that the Cys32 played a dominant role in the labeling between the probes and GSTO1. In addition, the molecular docking was suggestive of a close distance between Cys32 and the chlorine atom in the probe 7S-P and 7X-P (Figs. S5 and S6 in Supporting information). Together, these results clearly demonstrated that 7S-P and 7X-P could covalently bind the Cys32 residue in GSTO1.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Binding site mapping and validation. (A) Schematic workflow of in situ identification of binding sites using DADPS. DADPS, dialkoxydiphenylsilane; FA, formic acid. (B) Representative MS/MS site-mapping data showing the identification of Cys32 as the main reacting site of 7S-P in whole live cells. (C) Representative MS/MS site-mapping data showing the identification of Cys32 as the main reacting site of 7X-P in whole live cells. (D) Schematic workflow of iFASP in recombinant GSTO1. (E) Representative MS/MS site-mapping data showing the identification of Cys32 as the main reacting site of 7S-P in recombinant GSTO1. (F) Representative MS/MS site-mapping data showing the identification of Cys32 as the main reacting site of 7X-P in recombinant GSTO1. (G) The fluorescence labeling of mutant GSTO1 by 7S-P and 7X-P. | |

We next carried out a structure-activity-relationship (SAR) study to delineate the reactivity of this new electrophilic warhead (Table S1 in Supporting information). Two considerations were taken to set up the compound library. First, the remained alkyne group will help to examine the reactivity and selectivity of final compounds in the level of complicated whole proteome. Second, the different substitutes were introduced into the position 4 that is close to the warhead of the new electrophilic warhead and could potentially tune the reactivity of the final compound. The library was successfully obtained according to the same synthetic scheme in Fig. 1B. The yields of the fourth step regarding the different substituents were shown in Table S2 (Supporting information). Totally, 15 pairs of isomeric compounds were obtained. Only sulfur-substituted isomers were obtained when the substitute was naphthalene ring and phenol group. The chemical structure of all the final compounds were verified correct by HRMS and NMR (Supporting information). The precursors of compounds 15S and 15X were further resolved by X-ray single crystal diffraction (Figs. S7 and S8, Tables S3–S6 in Supporting information). We subsequently checked the labeling profile of these 34 compounds in the whole proteome. As shown in Fig. 4, compounds 8S, 8X, 15S and 15X exhibited highest reactivity among all compounds and multiple bands appeared in the fluorescence SDS-PAGE gel. This result indicated that benzene ring with electron-withdrawing groups could make the 1,2,4-triazole more electron-deficient and thereby increase the reactivity of this new warhead. Notably, if the benzene rings with electron-withdrawing group and 1,2,4-triazole were separated by a methyl group, the corresponding compounds (13S, 13X) would have lower labeling ability than 8S and 8X. On the contrary, compounds (12S, 12X) embed benzene ring with electron-donating groups had much weak labeling ability. These results indicate that the electron property of the substitutes could have significant effect on the labeling profile in the whole proteome. In addition, the compounds 16S, 16X, 17S, 17X, 18S and 18X almost lost the ability to covalently label the proteins. In these compounds, the two ortho positions of substituted benzene ring were occupied with a methyl group or chloro atom, suggesting the bulky steric effect would protect the chloromethyl group and inhibit its reactivity towards the protein targets. When the group was alkyl group, substituted alkyl group, or bicyclic aromatic ring, their corresponding compounds (10S, 10X, 11S, 11X, 12S, 12X, 22S, 22X, 23X and 24X) had moderate reactivity to label the proteome. Interestingly, various labeling patterns were observed when the position 4 was methyloxyl-substituted benzene ring. Compounds 19S and 19X with the methyloxyl group at ortho position showed significantly low reactivity but most specific labeling among all the compounds in the library. Compounds 20S, 20X, 21S and 21X with the methyloxyl group at meta or para position showed much higher reactivity, especially for compound 20X. Regarding the difference of protein labeling between the two kinds of regioisomers, no consistent pattern was observed. For example, most of regioisomers had roughly similar labeling, but N-substituted regioisomers (10S, 11S, 12S, 14S, 15S and 20S) had lower reactivity than their corresponding S-substituted regioisomers (10X, 11X, 12X, 14X, 15X and 20X), whereas N-substituted regioisomers (21S and 22S) had much higher reactivity than their corresponding S-substituted regioisomers (21X and 22X). Regarding the cellular inhibition, the compounds 16S, 16X, 17S, 17X, 18S and 18X without covalent labeling ability did not show any inhibitory effect even at the concentration of 20 µmol/L. The IC50 value of rest compounds ranged from 1.0 µmol/L to 18.5 µmol/L. Taking the proteome reactivity and anti-cancer effect into account, we selected compound 19S and 19X for the subsequent study.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. An examination of the reactivity and selectivity of new electrophilic warheads. The structure of newly-synthesized isomeric probes (A) and their profiles of labeling pattern in HCT116 cells under the same condition (B). | |

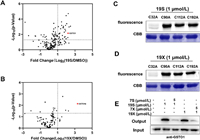

We then examined whether compounds 19S and 19X could still bind GSTO1. The LC-MS/MS analysis of peptides generated by tryptic digestion of the recombinant GSTO1 treated with 19S and 19X indicated that they could also bind Cys32 of GSTO1 (Figs. 5A and B, Figs. S9 and S10 in Supporting information). In addition, the Cys32 is still the dominant binding site for compounds 19S and 19X as the mutation of Cys32 almost abolished the binding (Figs. 5C and D). In the level of whole proteome, the covalent interaction between GSTO1 and compounds 19S and 19X was also confirmed by the examination of pull-down samples via WB and MS (Fig. 5E). Nevertheless, compounds 19S and 19X could also bind other proteins besides GSTO1 (Figs. 5A and B). Regarding the cellular activity, both 19S and 19X efficiently inhibited the growth of HCT116 cells and their IC50 value were 6.19 and 5.65 µmol/L, respectively. Finally, we explored the underlying mechanism of compounds 19S and 19X in inhibiting cancer cell proliferation or inducing cell death. Stemness traits of cancer cells have close relationship with their proliferation. Therefore, flow cytometry and WB were used to detect the change of colorectal cancer (CRC) stemness under the treatment of 19S and 19X. Stem cell marker (CD44) and three critical stemness related transcriptional factors (cellular-myelocytomatosis viral oncogene (c-Myc), octamer-binding transcription factor (OCT4) and SRY-related HMG-box gene 2 (SOX2)) were detected in HCT116 cells under the treatment of 19S and 19X. The results showed that these two compounds have no effects on the stemness traits of CRC cells (Figs. 6A–D, Fig. S11 in Supporting information), suggesting that the two compounds may play critical role in inducing cell death. Hence, to define the mode of cell death, the cells were pre-treated with different inhibitors, autophagy inhibitor (3-methyladenine, 3-MA), the necrosis inhibitor (GW806742X, GW), the ferroptosis inhibitor (ferrostatin-1, Fer-1), or the pan-caspase inhibitor (Z-VAD-FMK), to determine whether these inhibitors could neutralize the cytotoxicity of 19S and 19X towards HCT116 cells by using cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay and propidium iodide (PI) staining. It turned out that only the pan-caspase inhibitor effectively prevented 19S-induced cell death (Figs. 6E and F), both the ferroptosis and pan-caspase inhibitor effectively prevented 19X-induced cell death (Figs. 6G and H). These results indicated that 19S worked through inducing cell apoptosis while 19X worked through inducing both cell apoptosis and ferroptosis (Fig. S12 in Supporting information). As a GSTO1 inhibitor, the inhibition effect of compound 19X on ferroptotic cell death may suggest a potential role of GSTO1 in the regulation of ferroptosis.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (A, B) Volcano plot of label-free quantitative LC-MS experiments of proteomes labeled with 19S or 19X (1 µmol/L) or DMSO (negative control). Fluorescence labeling of mutant GSTO1 by 19S (C) and 19X (D). (E) Competitive labeling of GSTO1 by 19S and 19X with 7S or 7X. The labeled proteomes were "clicked" with biotin reporter ('input'), pulled down by avidin beads and eluted by boiling the beads ('output'). The input and output samples were analyzed by anti-GSTO1 immunoblotting. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. The biological function of 19S and 19X in HCT116 cells. (A, B) The effects of 19S (A) and 19X (B) (15 µmol/L, 24 h) on CD44 expression in HCT116 cells analyzed by flow cytometry. (C, D) The dose-effect of 19S (C) and 19X (D) (24 h) on c-Myc, OCT4 and SOX2 expression in HCT116 cells analyzed by Western blot. GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase. (E, G) The viability of HCT116 cells treated with 19S (E) or 19X (G) or together with 3-MA (2.5 mmol/L), GW806742X (10 µmol/L), ferrostatin-1 (5 µmol/L) or Z-VAD-FMK (10 µmol/L), n = 5 per group, one-way ANOVA test. (F, H) The percentage of PI + HCT116 cells treated with 19S (F) or 19X (H) or together with 3-MA (2.5 mmol/L), GW806742X (10 µmol/L), ferrostatin-1 (5 µmol/L) or Z-VAD-FMK (10 µmol/L), n = 3 per group, one-way ANOVA test. Unless specified otherwise, the data are presented as means ± standard error of mean (SEM). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001. | |

In summary, we have identified pairs of novel isomeric covalent inhibitors based on the core motif of 1,2,4-triazole. These pairs of regioisomers could be simultenously synthesized in alkylation of thiol-substituted 1,2,4-triazole and readily separated by flash chromatography. Using the model compounds of 7S-P and 7X-P, we have successfully proved that the new electrophilic warheads could covalently modify the Cys32 of GSTO1 in the levels of whole proteome and pure protein. This motif could be easily modified to generate a library of compounds. We also found that the reactivity of this new electrophilic warhead could be efficiently tuned by introduction of bulky groups in the nearby position. And compounds 19S and 19X with the methyloxyl group at ortho position showed lowest reactivity but most specific labeling among all the compounds in the library. Interestingly, 19S could induce the apoptosis of HCT116 cells while 19X induced apoptosis and ferroptosis. This difference in the modes of cell death indicated that two compounds could serve as a pair of tool compounds to study the protein regulators of apoptosis and ferroptosis in future. In conclusion, our study provides pairs of new electrophilic warheads that will serve as useful tools in medicinal chemistry, chemical biology and pharmacology.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the following funding: The National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22177136), CAMS Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (CIFMS, Nos. CIFMS-2021-I2M-1-007, 2022-I2M-2-002).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109034.

| [1] |

J. Singh, R.C. Petter, T.A. Baillie, A. Whitty, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 10 (2011) 307-317. DOI:10.1038/nrd3410 |

| [2] |

H.J. Benns, C.J. Wincott, E.W. Tate, M.A. Child, Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 60 (2021) 20-29. DOI:10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.06.011 |

| [3] |

A. Cuesta, J. Taunton, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 88 (2019) 365-381. DOI:10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044805 |

| [4] |

S. Sen, N. Sultana, S.A. Shaffer, P.R. Thompson, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 19257-19261 143. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c07069 |

| [5] |

J.A.H. Schwobel, Y.K. Koleva, S.J. Enoch, et al., Cronin. Chem. Rev. 111 (2011) 2562-2596. DOI:10.1021/cr100098n |

| [6] |

R.A. Bauer, Drug Discov. Today 20 (2015) 1061-1073. DOI:10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.005 |

| [7] |

M.H. Potashman, M.E. Duggan, J. Med. Chem. 52 (2009) 1231-1246. DOI:10.1021/jm8008597 |

| [8] |

F. Cameron, M. Sanford, Drugs 74 (2014) 263-271. DOI:10.1007/s40265-014-0178-8 |

| [9] |

S.B. Wagh, V.A. Maslivetc, J.J. La Clair, A. Kornienko, ChemBioChem 22 (2021) 3109-3139. DOI:10.1002/cbic.202100171 |

| [10] |

H. Johansson, Y.C.I. Tsai, K. Fantom, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 2703-2712. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b13193 |

| [11] |

E. Resnick, A. Bradley, J.R. Gan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 8951-8968 141. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b02822 |

| [12] |

K. Bum-Erdene, M.K. Ghozayel, D. Xu, S.O. Meroueh, ChemMedChem 17 (2022) e202100750. DOI:10.1002/cmdc.202100750 |

| [13] |

K.M. Backus, B.E. Correia, K.M. Lum, et al., Nature 534 (2016) 570-574. DOI:10.1038/nature18002 |

| [14] |

A. Douangamath, D. Fearon, P. Gehrtz, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 5047. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-18709-w |

| [15] |

T. Wirth, K. Schmuck, L.F. Tietze, S.A. Sieber, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51 (2012) 2874-2877. DOI:10.1002/anie.201106334 |

| [16] |

N. Panyain, A. Godinat, T. Lanyon-Hogg, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 12020-12026. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c04527 |

| [17] |

Y.C. Chen, K.M. Backus, M. Merkulova, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 639-642. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b12511 |

| [18] |

Z. Ye, K. Wang, L.G. Chen, et al., Acta Pharm. Sin. B 12 (2022) 982-990. DOI:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.09.003 |

| [19] |

Z.M. Li, K.K. Liu, P. Xu, J. Yang, J. Proteome Res. 21 (2022) 1349-1358. DOI:10.1021/acs.jproteome.2c00174 |

| [20] |

J.Q. Xu, Z. Zhang, L.G. Lin, ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 11 (2020) 535-540. DOI:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00658 |

| [21] |

H.X. Fang, B. Peng, S.Y. Ong, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 8288-8310. DOI:10.1039/D1SC01359A |

| [22] |

Z. Ye, Y.K. Wang, H. Wu, et al., ChemBioChem 22 (2021) 129-133. DOI:10.1002/cbic.202000527 |

| [23] |

T. Wang, Y. Zhou, H. Zheng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107887. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107887 |

| [24] |

M.M. Savitski, F.B.M. Reinhard, H. Franken, et al., Science 346 (2014) 55. |

| [25] |

J.M. Dziekan, G. Wirjanata, L.Y. Dai, et al., Nat. Protoc. 15 (2020) 1881-1921. DOI:10.1038/s41596-020-0310-z |

| [26] |

D.A.E. Cross, S.E. Ashton, S. Ghiorghiu, et al., Cancer Discov. 4 (2014) 1046-1061. DOI:10.1158/2159-8290.CD-14-0337 |

| [27] |

M. Bogyo, J.S. McMaster, M. Gaczynska, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 (1997) 6629-6634. DOI:10.1073/pnas.94.13.6629 |

| [28] |

A. Kung, Y.C. Chen, M. Schimpl, et al., Am. Chem. Soc. 33 (2016) 10554-10560. |

| [29] |

F. Ni, A. Ekanayake, B. Espinosa, et al., Biochemistry 58 (2019) 2715-2719. DOI:10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00359 |

| [30] |

C. Wang, D. Abegg, D.G. Hoch, A. Adibekian, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 2911-2915. DOI:10.1002/anie.201511301 |

| [31] |

N. Shindo, H. Fuchida, M. Sato, et al., Nat. Chem. Biol. 15 (2019) 250-262. DOI:10.1038/s41589-018-0204-3 |

| [32] |

Z.L. Liu, J. Li, S.H. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 2919-1925. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b12788 |

| [33] |

J. Dong, L. Krasnova, M.G. Finn, K.B. Sharpless, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 126 (2014) 9584-9603. DOI:10.1002/ange.201309399 |

| [34] |

M. Zeng, Y. Xue, Y. Qin, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4891-4895. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.075 |

| [35] |

E. Ghobadi, S. Saednia, S. Emami, Eur. J. Med. Chem. 231 (2022) 114161. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114161 |

| [36] |

C.L. Li, Z.X. Fang, Z. Wu, et al., Biomed. Pharmacother. 154 (2022) 113616. DOI:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113616 |

| [37] |

P. Polucci, P. Magnaghi, M. Angiolini, et al., J. Med. Chem. 56 (2013) 437-450. DOI:10.1021/jm3013213 |

| [38] |

S.J. Liu, P.P. Guo, K. Wang, et al., J. Med. Chem. 65 (2022) 10285-10299. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.1c02115 |

| [39] |

E.S. Al-Abdullah, H.H. Asiri, S. Lahsasni, et al., Drug. Des. Dev. Ther. 8 (2014) 505-518. |

| [40] |

L. Navidpour, M. Amini, A. Shafiee, J. Heterocyc. Chem. 44 (2007) 1323-1331. DOI:10.1002/jhet.5570440614 |

| [41] |

S.S. Jiang, H. Tanji, K. Yin, et al., J. Med. Chem. 63 (2020) 4117-4132. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b02128 |

| [42] |

T. Plech, M. Wujec, U. Kosikowska, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 60 (2013) 128-134. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2012.11.040 |

| [43] |

M. Koparir, C. Orek, A.E. Parlak, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 63 (2013) 340-346. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.02.025 |

| [44] |

A.S. Galstyan, T.V. Ghochikyan, V.R. Frangyan, R.A. Tamazyan, A.G. Ayvazyan, ChemistrySelect 3 (2018) 9981-9985. DOI:10.1002/slct.201802243 |

| [45] |

M. Nikpour, H. Motamedi, Chem. Heterocyc. Compd. 51 (2015) 159-161. DOI:10.1007/s10593-015-1674-9 |

| [46] |

X. Collin, A. Sauleau, J. Coulon, Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 13 (2003) 2601-2605. DOI:10.1016/S0960-894X(03)00378-0 |

| [47] |

S. Lai, Y. Chen, F. Yang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 14 (2022) 10320-10329. |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35