b Laboratory of Nuclear Energy Chemistry, Institute of High Energy Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Nuclear energy has received a lot of attention because of its unique and huge advantages over traditional fossil energy and it is easier to store than other new energy sources such as solar and wind. Closed nuclear fuel cycle is the inevitable choice for the sustainable development of nuclear energy, it recovers a lot of unreacted 235U and newly produced 239Pu in the spent nuclear fuel (SNF), which moderately improves the utilization rate of uranium resources and reduces the volume of radioactive waste [1]. SNF reprocessing is indispensable to achieving the closed nuclear fuel cycle [2], which recovers most of the uranium (U) and plutonium (Pu). Plutonium Uranium Reduction EXtraction (PUREX) process uses tributyl phosphate (TBP) as the extractant to extract most of the U(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) from SNF into the organic phase. However, lanthanides (Ln) and trans-plutonium actinides, such as Am(Ⅲ) and Cm(Ⅲ) are present in the high-level liquid waste (HLLW) from the PUREX process, which complicates the SNF reprocessing due to their similar chemical properties [3]. Neptunium-237 (237Np) produced by nuclear power reactors has a long half-life of 2.144 million years, which leads to tremendous challenges for the geological repository. Moreover, 237Np by neutron irradiation can be prepared into plutonium-238, which is made into uninterrupted cardiac pacemakers and nuclear batteries [4]. Therefore, it is highly necessary to separate Np or Pu from SNF individually due to their potential applications. However, it is extraordinarily difficult to achieve the sole separation of Np or Pu in the reprocessing process such as high HNO3 concentration, strong radioactivity, and complex valence state. In the PUREX process, the extraction ability of the three valence states Np by TBP follows the order of Np(Ⅵ) > Np(Ⅳ) > > Np(Ⅴ) [5,6]. Besides, the extraction ability of TBP for the two valence states Pu is Pu(Ⅳ) > > Pu(Ⅲ) [6]. Therefore, it is vital to effectively adjust and control the Np(Ⅴ) in the PUREX process, so that Np(Ⅴ) remains in the aqueous solution, while Pu(Ⅳ) can be extracted into the organic phase with TBP.

A variety of free-salt reductants including hydroxylamines [7–11], oximes [12–15], hydroxyurea [16,17], aldehydes [18–20], hydrazine [5,21–28] and their derivatives have been explored to reduce Np(Ⅵ). A salt-free reductant is one whose reduction products are only unsalted compounds such as alcohols, aldehydes, nitrogen gas, and oxides of nitrogen [29]. Most free-salt reductants can reduce Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) to Np(Ⅴ) and Pu(Ⅲ), respectively, which allows Np(Ⅴ) and Pu(Ⅲ) to enter the aqueous phase together. For instance, Marchenko et al. reported that hydroxylamine can rapidly reduce Np(Ⅵ)/Pu(Ⅳ) to Np(Ⅴ)/Pu(Ⅲ) at 0.33 mol/L HNO3 solution, respectively [10]. Koltunov et al. also found that Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) can be reduced by acetaldoxime to Np(Ⅴ) and Pu(Ⅲ), respectively, but their reaction mechanism is different possibly [12]. Yan et al. proposed that dihydroxyurea (DHU) can speedily reduce Pu(Ⅳ)/Np(Ⅵ) to Pu(Ⅲ)/Np(Ⅴ), respectively [16,17]. However, a few free-salt reductants are merely able to reduce Np(Ⅵ) to Np(Ⅴ) while not reducing Pu(Ⅳ), which achieves the separation of Np from Pu. On the basis of this point, some advanced PUREX processes such as SUPERPUREX process [30] and Partitioning Conundrum Key (PARC) process [31] were proposed to achieve the separation of Np. The investigations of hydrazine derivatives to only reduce Np(Ⅵ) but not Pu(Ⅳ) have also received much attention [5,21,22,27]. Uchiyama et al. proved that n-butyraldehyde selectively reduces Np(Ⅵ) without reducing Pu(Ⅳ) and U(Ⅵ) [18]. Methylhydrazine (CH3N2H3) shows a significant difference in reduction rate for the Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) [21], which has potential application for the separation of Np from Pu in SNF reprocessing [21,27]. In addition, the Np(Ⅵ)/Pu(Ⅳ) separation can be affected by the concentration of the nitric acid solution. CH3N2H3 easily reduces Np(Ⅵ) in 3 mol/L compared to 1 mol/L HNO3 solution, while it appears the opposite trend for the reduction of Pu(Ⅳ). Therefore, Np/Pu separation is more easily achieved with CH3N2H3 in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution [22]. However, the reasons for the difference between the reduction rate for Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) by CH3N2H3 are not fully clarified. Therefore, it is an indispensable component to investigate the reaction mechanisms of Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) with CH3N2H3 through theoretical calculations. Besides, previous theoretical works reported the reaction mechanisms of the main group, transition metals, and rare earth metals [32–38], but comparatively less for actinides, largely owing to their complex electronic structures [39–45].

We have theoretically scrutinized the reaction mechanisms of Np(Ⅵ) with hydrazine [26], and its derivatives in aqueous solution [28,46,47]. Unlike the previous reports, in this work, to elucidate in-depth the difference between the reduction rate of Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) by CH3N2H3, we investigated and compared their reduction mechanism. Furthermore, considering that the reduction reaction occurs in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution, we also clarified the effect of nitrate ion participation on the energy barrier of the reduction pathways. This work investigates the reduction mechanism of the Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) by methylhydrazine in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution and unravels their differences in reduction mechanism using theoretical methods. This work also provides valuable perspectives for understanding the reaction mechanism and rate for Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) by CH3N2H3 in HNO3 solution, which contributes to the experimental studies of Np/Pu separation in spent nuclear fuel reprocessing.

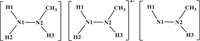

Reduction mechanisms of Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) with CH3N2H3 were studied using the B3LYP functional within the Gaussian 16 program [48], as reported previously in calculations of actinide complexes [49–54]. The relativistic effective core potential (RECP) [55] with 60 core electrons and the corresponding ECP60MWB-SEG valence basis set [56,57] were used for Pu and Np; the 6-31G(d) basis set was applied for C, O, N, and H [58,59]. The solvation effect impacts the rate, equilibrium, and mechanism of the reaction [60]. To evaluate the impact of the solvation effect, we calculated the solvation energy of the structures of IC1Ⅰ, TS1Ⅰ, INT1Ⅰ, TS2Ⅰ, and INT2Ⅰ for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3 (Table S1 in Supporting information). It shows that the solvation energy in the five complexes is −92 ~ −106 kcal/mol, which indicates that the impact of the solvation effect is sensitive to the structures we studied here. We tested the solvation optimization using the solvation model density (SMD) [61] and conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) approach with Klamt's radii [62] for the [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ structure, which is the major species of Pu(Ⅳ) in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution with the Pu coordination number of 11 [63,64]. The 10-coordinated and 11-coordinated structure of Pu(Ⅳ) ion for the [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ is obtained using the SMD and CPCM models, respectively (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). This result indicates that the CPCM model is more suitable for the optimization of Pu(Ⅳ) systems. Therefore, we performed the geometrical optimizations with the CPCM model using water (ε = 78.3553). To explore the effect of the SMD and CPCM models on the reaction barrier, we also performed the single point calculations for the optimal pathway of the reduction of Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) by CH3N2H3 with the SMD model. The results suggest that the two solvation models have similar PEPs, as shown in Figs. S2 and S3 (Supporting information). SMD model is recommended to compute the solvation energy [65,66], so we chose SMD model to discuss the solvation effects in this work. The solvation free energy of H+ is set to be −264.0 kcal/mol [67]. Gibbs free energy is used for the calculations of the potential energy profiles (PEPs) [68]. In addition, to test the effect of the basis set on the PEPs, we have carried out the single point energy calculations for each structure of pathway Ⅰ in the aqueous phase with the larger basis set 6-311++G(d, p). These results show that the PEPs do not affect the trend of PEPs as discussed below. All Np(Ⅵ/Ⅴ) and Pu(Ⅳ/Ⅲ) complexes were carried out in the highest spin state as the ground state with the spin-unrestricted method. There is only one imaginary frequency for each transition state and the frequencies of all initial complexes and intermediates are positive values at the same level of theory. Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations were performed to ensure that TSs are connected to ICs and INTs. Mayer bond orders (MBOs) and the localized molecular orbitals (LMOs) [69] with the Multiwfn code [70] were carried out based on the optimized structures to evaluate bonding evolution. Atom labels for the CH3N2H3, free radical ion [CH3N2H3]+•, and free radical [CH3N2H2]• are shown in Scheme 1. The abbreviations used in this work are as follows: ICs = initial complexes, TSs = transition states, INTs = intermediates.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Atom labels for CH3N2H3, [CH3N2H3]+•, and [CH3N2H2]•. | |

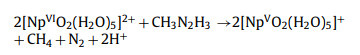

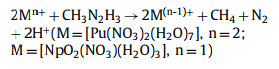

In general, the distribution of Np(Ⅵ) is 70% [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ and 30% [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ species at 3 mol/L HNO3 solution [71–73], which indicates that [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ is the predominant species compared to [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ [71]. [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ is the dominant species of Pu(Ⅳ) at 3 mol/L HNO3 solution [63,64,74,75], and its structure has been confirmed by the extended X-ray absorption fine-structure (EXAFS) spectra, in which seven water molecules and two bidentate nitrate ions are coordinated to Pu(Ⅳ) ion [63]. Therefore, we considered [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+, [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+, and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ as the initial species. The free radical ion mechanism and free radical mechanism of [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ by CH3N2H3 in aqueous phase have been investigated in detail in our previous work [28], and the total reaction equation is expressed as:

|

(1) |

In this work, we primarily focused on the reduction mechanisms of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ by CH3N2H3.

According to the experimental observations [23], the overall reaction equation for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ by CH3N2H3 is expressed as:

|

(2) |

where one CH3N2H3 molecule achieves the reduction of two Mn+ complexes.

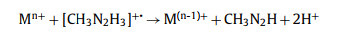

Based on the different products after the first Mn+ complex reduction, there are the free radical ion mechanism (pathway Ⅰ) and free radical mechanism (pathway Ⅱ) for the reduction reactions. The free radical ion mechanism is listed as:

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

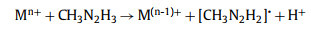

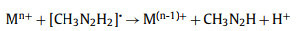

Also, the free radical mechanism presents as

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

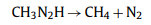

Both mechanisms yield an identical intermediate product (CH3N2H), which forms stable methane and nitrogen:

|

(7) |

Pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ have the same stage for the first [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+/[PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ reduction.

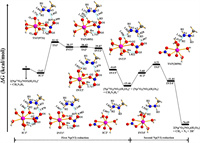

To test the effect of the basis set on the PEPs, we have performed the single-point energy calculations for each structure of pathway Ⅰ in the aqueous phase with the larger basis set 6-311++G(d, p). It shows that the value of relative energy for each structure is different under the 6-31G(d) (Fig. 1) and 6-311++G(d, p) basis sets (Fig. S4a in Supporting information), but the trend of the PEPs with both basis sets is similar. Similar results are also obtained for the reduction of Pu(Ⅳ) (Fig. S4b in Supporting information). To balance the calculation of cost and time, we discussed the results of the PEPs using the 6-31G(d) basis set. The PEPs based on Gibbs free energy for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3 are shown in Fig. 1. The process from IC1 to INT2 for pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ is the same, subsequently INT2 dissociates into [CH3N2H3]+• and [CH3N2H2]• which acts as the reductant of the second stage of pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ, respectively. The energy barrier of TS1 is significantly larger than that of TS2 and TS3 for the two pathways, indicating that the first stage from IC1 to TS1 is a rate-limiting step. The lowest energy barrier (1.05 kcal/mol) of the second stage for pathway Ⅱ indicates free radical mechanism is the optimal reaction pathway.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. PEPs for the two [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ reduction by one CH3N2H3. The first stage of pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ is the same. The second Np(Ⅵ) reduction includes the second stages of pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ. | |

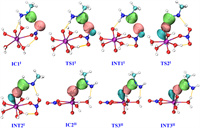

PEP, structures of INTs, ICs, and TSs, and the TSs imaginary frequencies for pathway Ⅰ are depicted in Fig. 2. The formation of IC1Ⅰ from [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and CH3N2H3 is a −3.63 kcal/mol exothermic process. IC1Ⅰ has four water molecules and one mono-dentate nitrate ion coordinated with neptunyl ion, of which the CH3N2H3 binds with [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by two hydrogen bonds with the distance of 1.864 and 1.870 Å. In addition, the oxygen atom of nitrate ion forms a 1.790 Å hydrogen bond with the hydrogen of the coordinated water molecule. Firstly, the reaction IC1Ⅰ → INT1Ⅰ is via TS1Ⅰ with a 35.95 kcal/mol energy barrier. As the reaction from IC1Ⅰ to TS1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ, the N2–H3 bond extends from 1.031 Å~1.842 Å to 2.148 Å, while the O1–H3 bond decreases from 1.870 Å~0.996 Å to 0.982 Å. This result indicates that the breaking of the N2–H3 bond of CH3N2H3 and the appearance of the O1–H3 bond of INT1Ⅰ, which is confirmed by the imaginary frequency of TS1Ⅰ corresponded to H3 stretching vibration between N2 and O1 atoms. The distance of the N1–N2 bond somewhat shortens from 1.324 Å of IC1Ⅰ to 1.256 Å of TS1Ⅰ to 1.231 Å of INT1Ⅰ as shown in Table S2 (Supporting information), while the corresponding Np-Oyl1 bond slightly increases from 1.824 Å to 1.842 Å and the Np-Oyl2 bond nearly keeps the same. In addition, from IC1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ, the N1–H2 and Oyl1-H2 bond distances become slightly longer and shorter, respectively. Subsequently, the reaction from INT1Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ only overcomes the 0.06 kcal/mol energy barrier via TS2Ⅰ. With the reaction from INT1Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ, the N1–H2 bond obviously extends from 1.062 Å to 1.660 Å, and the Oyl1-H2 bond significantly shortens from 1.667 Å to 1.032 Å, indicating that the H2 atom is transferred to Oyl1 through TS2Ⅰ. TS2Ⅰ has a 485i cm−1 imaginary frequency, corresponding to N1–H2–Oyl1 stretching vibration. The N2–H3 bond distance decreases by 0.274 Å from INT1Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ. It is an exothermic process (−30.51 kcal/mol) with the structural change from INT2Ⅰ to INT3Ⅰ accompanied by the formation of the N1–H2 and N2–H3 bonds in INT3Ⅰ. Then, INT3Ⅰ is dissociated into [NpⅤO2(NO3)(H2O)3] and free radical ion [CH3N2H3]+• which serves as the following reductant. Some hydrazine derivatives radical ions can exist in acidic solution, for instance, methylhydrazine and dimethylhydrazine radical cations in reduction processes have been recognized by electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra earlier [76]. Moreover, methylhydrazine, hydrazine, and dimethylhydrazine radical cations were recognized by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy [77,78]. Therefore, [CH3N2H3]+• is very likely accessible to the second Np(Ⅵ) ion. The Gibbs free energy change (∆G) of Eq. 3 is −15.46 kcal/mol, indicating the first [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ reduction by CH3N2H3 is thermodynamically accessible.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. PEP and structures for pathway Ⅰ for the reduction of two [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by one CH3N2H3. Values in parentheses are TS imaginary frequencies (cm−1). Oyl1 and Oyl2 indicate neptunyl oxygen atoms that participated or not participated in bonding, respectively. O1, O2, and O3 are oxygen atoms in the nitrate ion. Ow and Hw are oxygen and hydrogen atoms of water, respectively. | |

Along with the reaction from IC2Ⅰ to INT4Ⅰ, the reduction of the second [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ is achieved by free radical ion [CH3N2H3]+•, which needs to overcome 7.81 kcal/mol energy barrier. In this process, the H2 atom of [CH3N2H3]+• gradually moves into the Oyl1 atom, leading to a shorter Oyl1-H2 bond and a longer N1–H2 bond. Finally, INT4Ⅰ dissociates into [NpⅤO2(NO3)(H2O)3], CH4, N2, and 2H+ based on the result of the previous work [47].

The first stage of pathways Ⅱ and Ⅰ is the same as discussed above. In the second stage, IC2Ⅱ has three water molecules and one bidentate nitrate ion coordinated with neptunyl ion (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). Noticeably, the nitrate ion only participates in the coordination, but does not participate in the reduction process of the second [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+. The free radical [CH3N2H2]• binds with the second [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by Oyl1-H3 and N1–Hw hydrogen bonds with a distance of 1.638 and 2.046 Å, respectively. The distance of the N2–H3 bond evidently extends from 1.069 (IC2Ⅱ) to 1.390 (TS3Ⅱ) and further extends to 1.628 Å (INT3Ⅱ), while the Oyl1-H3 distance sharply shortens from 1.638 (IC2Ⅱ) to 1.137 (TS3Ⅱ) to 1.042 Å (INT3Ⅱ). Breaking of the N2–H3 bond in [CH3N2H2]• and formation of the Oyl1-H3 bond in INT3Ⅱ are confirmed by the N2–H3–Oyl1 stretching vibration of TS3Ⅱ with a 360i cm−1 imaginary frequency. Along with the H3 atom of [CH3N2H2]• gradually moves toward the Oyl1 atom, the N1–Hw hydrogen bond somewhat shortens from 2.046 Å in IC2Ⅱ to 1.818 Å in INT3Ⅱ. Finally, INT3Ⅱ dissociates into [NpⅤO2(NO3)(H2O)3], CH4, N2, and H+, which is a similar process as reported in previous work [47].

The optimal mechanism of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ by CH3N2H3 is the free radical mechanism with the rate-limiting step of the first stage. The energy barrier for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ by CH3N2H3 is 8.59 kcal/mol using SMD model [28], which is significantly lower than that for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ with the value of 35.95 kcal/mol using SMD model (Fig. 2). This result indicates that CH3N2H3 is easier to reduce [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ compared to [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+, probably due to the participation of nitrate ion in the reduction process of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+. Moreover, [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ is the predominant species in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution [71]. According to the energy barrier for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ and [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+, when all of the [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ complexes in solution are reduced, [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ can also be reduced.

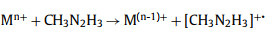

We have investigated the reduction of [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ by CH3N2H3, and also obtained two pathways, as presented in Fig. 3. Similarly, the first pathway Ⅰs the free radical ion mechanism, and the second pathway Ⅰs the free radical mechanism. The energy barrier of the reduction for the first Pu(Ⅳ) is obviously higher than that of the reduction for the second Pu(Ⅳ), suggesting that the first Pu(Ⅳ) reduction is the rate-limiting step. Moreover, the somewhat lower energy barrier of pathway Ⅱ reveals that free radical mechanism is a favorable reaction pathway.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. PEPs for the reduction of two [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ by one CH3N2H3. The first stage of pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ is the same. | |

PEP and the relevant structures for pathway Ⅰ of the [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ reduction by CH3N2H3 as shown in Fig. 4. IC1Ⅰ was formed by a −25.70 kcal/mol exothermic process. The structure of IC1Ⅰ has seven water molecules and one bidentate and monodentate nitrate ions coordinated with Pu(Ⅳ) ion. CH3N2H3 binds with [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ by two hydrogen bonds; one is between H2 atom of CH3N2H3 and O1 atom of the monodentate nitrate ion with a distance of 1.848 Å, the other is between H3 atom and Ow atom with the distance of 1.859 Å. In addition, O3 atom of the monodentate nitrate ion and Hw atom also forms a hydrogen bond with a distance of 1.762 Å. Subsequently, the H2 atom of CH3N2H3 is transferred to the O1 atom of nitrate ion via TS1Ⅰ with an energy barrier of 35.91 kcal/mol using SMD model. In this process, the distance of the N1–H2 bond firstly increases substantially from 1.032 (IC1Ⅰ) to 1.826 (TS1Ⅰ) and then increases slightly to 2.061 Å (INT1Ⅰ), while the corresponding O1–H2 bond distance firstly decreases sharply from 1.848 to 0.996, and then decreases mildly to 0.983 Å. However, the N2–H3 and Ow-H3 bond distances are almost similar in the structures from IC1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ. These results show that as the reaction moves from IC1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ, the N1–H2 bond breaks and the O1–H2 bond forms, which is confirmed by the vibrational mode of imaginary frequency in TS1Ⅰ with a value of 1067i cm−1. Besides, Table S3 shows that the N1–N2 bond decreases by 0.094 Å from IC1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ, and the corresponding Pu–O2 bond also decreases by 0.155 Å. Then, INT1Ⅰ is dissociated into [PuⅢ(NO3)2(H2O)7]+ and free radical ion [CH3N2H3]+•. The value of ∆G for Eq. 3 is −30.60 kcal/mol, indicating the first [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ reduction is thermodynamically accessible.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. PEP and relevant structures of pathway Ⅰ for the [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ reduction by CH3N2H3. Values in parentheses are TS imaginary frequencies (cm−1). | |

It overcomes 15.65 kcal/mol energy barrier for the reduction of the second [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+, which is lower than that for the first Pu(Ⅳ) reduction. The H2 atom of [CH3N2H3]+• in IC2Ⅰ gradually transfers into the O1 atom along with the reaction from IC2Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ, which leads to the longer N1–H2 bond and the shorter O1–H2 bond. Interestingly, Pu(Ⅳ) ion has the same coordination numbers in IC2Ⅰ and INT2Ⅰ, but the corresponding coordination environment is significantly different. Finally, INT2Ⅰ dissociates into [PuⅢ(NO3)2(H2O)7]+, CH4, N2, and 2H+, with a strongly exothermic process.

The first stage of pathway Ⅱ is the same as that of pathway Ⅰ. For the second stage, the Pu(Ⅳ) coordination structure in IC2Ⅱ is similar to that in IC1Ⅱ, as shown in Fig. S6 (Supporting information). There are two O1–H3 and N1–Hw hydrogen bonds with a distance of 1.710 and 2.045 Å in the structure of IC2Ⅱ, respectively. From IC2Ⅱ to INT2Ⅱ, the distance of the N2–H3 bond dramatically extends from 1.062 Å (IC2Ⅱ) to 1.462 Å (TS2Ⅱ) and gradually extends to 1.509 Å (INT2Ⅱ). The corresponding O1–H3 bond significantly decreases from 1.710 Å to 1.085 Å (Fig. S6). The distance of the N2–H3 bond in IC2Ⅱ and TS2Ⅱ is longer than that of the N1–H2 bond in IC2Ⅰ and TS2Ⅰ, which reflects the ability of the hydrogen transfer. The reaction from IC2Ⅱ to INT2Ⅱ needs to overcome a 1.77 kcal/mol energy barrier, which is significantly lower than that from IC2Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ in pathway Ⅰ (15.65 kcal/mol). The formation of IC2Ⅰ is an exothermic process with an energy of 47.72 kcal/mol, which is similar to that of the formation of IC2Ⅱ (46.55 kcal/mol).

LMOs is a very useful method to uncover bond characteristics and evolution for the reaction process. The diagrams of LMO for the structures of pathway Ⅱ for the [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ are shown in Fig. 5 and Fig. S7 (Supporting information) and those of pathway Ⅰ are presented in Figs. S8 and S9 (Supporting information). As shown in Fig. 5, the breaking of the N2–H3 σ bond and the appearance of the O1–H3 σ bond happen as the reaction goes from IC1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ. Also, the N1–H2 σ bond in CH3N2H3 is broken and the Oyl1-H2 σ bond is formed when the reaction moves from INT1Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ. Similarly, the breaking of the N2–H3 σ bond in [CH3N2H2]• and the formation of the Oyl1-H3 σ bond in the reduction process of the second [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ is obvious. Fig. S7 also indicates the structural evolution of the [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ reduction by CH3N2H3. In addition, Mayer bond orders (Tables S2–S5 in Supporting information) for structures of the pathways also reveal the change of the N1–N2 and Np-Oyl1/Pu–O bonds with the evolution of the reaction.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Diagrams of LMOs for the relevant structures of pathway Ⅱ for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3 (isovalue = 0.08). The yellow line of dashes indicates hydrogen bonds; Purple, cyan, red, white, and blue balls represent Np, C, O, H, and N atoms, respectively. The structures of the first stage for pathways Ⅰ and Ⅱ are the same. | |

Spin density is used to reflect the oxidation state of the metal atom, as reported in previous work by Mallik and Gorantla [79]. Diagrams of spin density of the structures for the pathway Ⅰ of the [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ reduction are shown in Fig. S10 (Supporting information) and the corresponding values on the Np, O, and N atoms are tabulated in Table S6 (Supporting information). The spin density on the Np atom for the structures from IC1Ⅰ to INT3Ⅰ is about 2.19~2.21 a.u., indicating that the oxidation state of Np is Np(Ⅴ) for these structures. This result shows that Np(Ⅵ) is reduced to Np(Ⅴ) as long as the CH3N2H3 binds to the Np(Ⅵ) ion. Moreover, the total value of the spin density located on N1 and N2 atoms in IC1Ⅰ is about 1.02 a.u., which clearly demonstrates that the CH3N2H3 fragment in IC1Ⅰ has radical character. The spin density located on N1 and N2 atoms gradually transfers to the nitrate ion as the reaction from IC1Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ. Subsequently, the spin density of nitrate ion is transferred to CH3N2H3 fragment in INT3Ⅰ, which leads to the formation of free radical ion [CH3N2H3]+•. Therefore, the first Np(Ⅵ) reduction is the outer-sphere electron transfer from CH3N2H3 to neptunyl ion in the formation of IC1Ⅰ, which is supported by previous works [80–82]. As for the second Np(Ⅵ) reduction, the spin density of Np atom increases from 1.160 a.u. (IC3Ⅰ) to 2.233 a.u. (INT4Ⅰ), while the spin density located on the N1 and N2 atoms of [CH3N2H3]+• gradually decreases from 1.017 a.u. to 0 a.u., indicating that Np(Ⅵ) in IC3Ⅰ is transformed to Np(Ⅴ) in INT4Ⅰ accomplished with the hydrogen transfer. Therefore, for pathway Ⅰ the first Np(Ⅵ) reduction is the outer-sphere electron transfer and the second Np(Ⅵ) reduction is the hydrogen transfer.

Diagrams of spin density of the structures for the pathway Ⅰ of the reduction of [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ by CH3N2H3 are shown in Fig. S11 (Supporting information) and the corresponding values on the Pu, O, and N atoms are listed in Table S7 (Supporting information). The value of spin density on the Pu atom is about 5.02~5.05 a.u. for the structures from IC1Ⅰ to INT1Ⅰ, revealing Pu(Ⅲ) oxidation state in these structures. This result also indicates that the first Pu(Ⅳ) reduction occurs when the CH3N2H3 binds to the Pu(Ⅳ) complex, which is the outer-sphere electron transfer from CH3N2H3 to Pu(Ⅳ) complex in the formation of IC1Ⅰ. Moreover, the values of the spin density located on the N1 and N2 atoms in IC1Ⅰ is 1.018 a.u., which suggests that CH3N2H3 fragment has radical character. As for the second Pu(Ⅳ) reduction, the spin density of Pu atom from IC2Ⅰ to INT2Ⅰ is about 5.04~5.05 a.u., which also indicates that the oxidation state of Pu is Ⅲ. The formation of IC2Ⅰ by [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ and [CH3N2H3]+• is accompanied by the breaking of N2–H3 bond of [CH3N2H3]+•, which leads to the second Pu(Ⅳ) reduction with the help of hydrogen transfer. Therefore, the first Pu(Ⅳ) reduction belongs to the outer-sphere electron transfer, while the second Pu(Ⅳ) reduction is the hydrogen transfer.

Overall, the free radical mechanism for the reduction of [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+, [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+, and [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3 is the optimal process. Noticeably, the energy barrier for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ by CH3N2H3 is 8.59 kcal/mol [28], which is remarkably smaller than that for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3 (35.95 kcal/mol) due to the involvement of nitrate ion in [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+. Moreover, [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ is the major species in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution [71]. Therefore, [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ is more quickly reduced than [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3 in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution. The energy barrier of the rate-limiting step for the free radical mechanism of the reduction of [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ is 35.91 kcal/mol. These results demonstrate that in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution CH3N2H3 is easier to reduce [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ than [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+, which is in line with the experimental results [21]. The activation barrier for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ is lower than that of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+, which accounts for the selective reduction of Np(Ⅵ) over Pu(Ⅳ).

The separation of Pu and Np has gained significant attention in spent nuclear fuel reprocessing, of which the key issue is to control their valence states. Hydrazine and some of its derivatives reduce Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ), while CH3N2H3 only reduces Np(Ⅵ) to Np(Ⅴ) without the reduction of Pu(Ⅳ), which can achieve the Np(Ⅴ)/Pu(Ⅳ) separation by TBP. The reduction mechanism of Pu(Ⅳ)/Np(Ⅵ) by CH3N2H3 in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution was systematically explored utilizing scalar-relativistic DFT calculations. We found that the free radical mechanism is the optimal reduction pathway for [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]+, [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+, and [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ by CH3N2H3. The energy barrier of the rate-limiting step for the reduction of [NpⅥO2(H2O)5]2+ by CH3N2H3 is greatly smaller than that of [NpⅥO2(NO3)(H2O)3]+ and [PuⅣ(NO3)2(H2O)7]2+ in 3 mol/L HNO3 solution due to the participation of nitrate ion, well explaining the experimental results. Results of LMOs and MBOs reveal the bonding changes in the structures of the PEPs. The results of the spin density uncover that the first Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) reduction is achieved in the process of the formation of IC1, which is the outer-sphere electron transfer. The second Np(Ⅵ) and Pu(Ⅳ) reduction is achieved by hydrogen transfer. This study clarifies the mechanism for the faster reduction rate of Np(Ⅵ) than Pu(Ⅳ) by CH3N2H3, which also provides valuable information for the design of environment-friendly reductants on the Np/Pu separation in spent nuclear fuel reprocessing.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. U2067212, 22376197, U1867205), the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 21925603).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109359.

| [1] |

B.F. Myasoedov, S.N. Kalmykov, Y.M. Kulyako, et al., Geochem. Int. 54 (2016) 1156-1167. DOI:10.1134/S0016702916130115 |

| [2] |

G.A. Ye, T.H. Yan, Development of Closed Nuclear Fuel Cycles in China, Elsevier, Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy, 2015, pp. 531–548. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-212-9.00020-4

|

| [3] |

C.A. Sharrad, D.M. Whittaker, The Use of Organic Extractants in Solvent Extraction Processes in the Partitioning of Spent Nuclear Fuels, Elsevier, Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy, 2015, pp. 153–189. 10.1016/B978-1-78242-212-9.00007-1

|

| [4] |

M. Precek, The Kinetic and Radiolytic Aspects of Control of the Redox Speciation of Neptunium in Solutions of Nitric Acid, Oregon State University, 2012.

|

| [5] |

Y. Ban, T. Asakura, Y. Morita, J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 279 (2009) 423-429. DOI:10.1007/s10967-007-7262-4 |

| [6] |

J. Chen, X.H. He, J.C. Wang, Radiochim. Acta 102 (2014) 41-51. DOI:10.1515/ract-2014-2093 |

| [7] |

V.I. Marchenko, V.S. Koltunov, O.A. Savilova, et al., Radiochemistry 43 (2001) 276-283. DOI:10.1023/A:1012812609241 |

| [8] |

A.Y. Zhang, J.X. Hu, X.Y. Zhang, et al., J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 253 (2002) 107-113. DOI:10.1023/A:1015872703102 |

| [9] |

V.I. Marchenko, V.S. Koltunov, K.N. Dvoeglazov, Radiochemistry 52 (2010) 111-126. DOI:10.1134/S1066362210020013 |

| [10] |

V.I. Marchenko, K.N. Dvoeglazov, O.A. Savilova, et al., Radiochemistry 54 (2012) 459-464. DOI:10.1134/S1066362212050074 |

| [11] |

V.I. Marchenko, V.N. Alekseenko, K.N. Dvoeglazov, Radiochemistry 57 (2015) 366-377. DOI:10.1134/S1066362215040050 |

| [12] |

V.S. Koltunov, R.J. Taylor, S.M. Baranov, et al., Radiochim. Acta 88 (2000) 65-70. DOI:10.1524/ract.2000.88.2.065 |

| [13] |

V.S. Koltunov, R.J. Taylor, S.M. Baranov, et al., J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 39 (2002) 878-881. DOI:10.1080/00223131.2002.10875609 |

| [14] |

V.S. Koltunov, E.A. Mezhov, S.M. Baranov, Radiochemistry 43 (2001) 342-345. DOI:10.1023/A:1012893432439 |

| [15] |

V.S. Koltunov, V.I. Marchenko, G.I. Zhuravleva, et al., Radiochemistry 43 (2001) 334-337. DOI:10.1023/A:1012889331531 |

| [16] |

T.H. Yan, W.F. Zhen, G.A. Ye, et al., J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 279 (2009) 293-299. DOI:10.1007/s11029-009-9081-x |

| [17] |

T.H. Yan, W.F. Zheng, C. Zuo, et al., Radiochim. Acta 98 (2010) 35-38. |

| [18] |

G. Uchiyama, S. Fujine, S. Hotoku, et al., Nucl. Technol. 102 (1993) 341-352. DOI:10.13182/NT93-A17033 |

| [19] |

G. Uchiyama, S. Hotoku, S. Fujine, et al., Solvent Extr. Ion Exc. 15 (1997) 863-877. DOI:10.1080/07366299708934510 |

| [20] |

G. Uchiyama, S. Hotoku, S. Fujine, et al., Nucl. Technol. 122 (1998) 222-227. DOI:10.13182/NT98-A2864 |

| [21] |

V.S. Koltunov, S.M. Baranov, Inorg. Chim. Acta 140 (1987) 31-34. DOI:10.1016/S0020-1693(00)81042-7 |

| [22] |

R.J. Taylor, I. May, V.S. Koltunov, et al., Radiochim. Acta 81 (1998) 149-156. DOI:10.1524/ract.1998.81.3.149 |

| [23] |

V. Koltunov, J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 39 (2002) 347-350. DOI:10.1080/00223131.2002.10875480 |

| [24] |

V.I. Volk, V.I. Marchenko, K.N. Dvoeglazov, et al., Radiochemistry 54 (2012) 143-148. DOI:10.1134/S1066362212020087 |

| [25] |

H. He, G.A. Ye, H.B. Tang, et al., Radiochim. Acta 102 (2014) 127-133. DOI:10.1515/ract-2014-2120 |

| [26] |

Z.P. Cheng, Q.Y. Wu, Y.H. Liu, et al., RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 109045-109053. DOI:10.1039/C6RA13339H |

| [27] |

Z.Y. Liu, H. Zhang, R.T. Wang, et al., Nucl. Tech. 40 (2017) 1-7. |

| [28] |

X.B. Li, Q.Y. Wu, C.Z. Wang, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 124 (2020) 3720-3729. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpca.0c01504 |

| [29] |

S. Li, Y.B. Gao, Y.G. Ou Yang, Nucl. Tech. 35 (2012) 929-935. |

| [30] |

E.A. Puzikov, B.Y. Zilberman, Y.S. Fedorov, et al., Radiochemistry 46 (2004) 149-156. DOI:10.1023/B:RACH.0000024940.58660.0f |

| [31] |

G. Uchiyama, H. Mineo, S. Hotoku, et al., Prog. Nucl. Energy 37 (2000) 151-156. DOI:10.1016/S0149-1970(00)00040-8 |

| [32] |

B. Zhu, W. Guan, L.K. Yan, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 11069-11072. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b02433 |

| [33] |

B.E. Haines, J.Q. Yu, D.G. Musaev, Chem. Sci. 9 (2018) 1144-1154. DOI:10.1039/c7sc04604a |

| [34] |

M.M. Tong, F.F. Sun, Y. Xie, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 14005-14012. DOI:10.1002/anie.202102053 |

| [35] |

W.L. Yu, Z.G. Ren, K.X. Ma, et al., Chem. Sci. 13 (2022) 7947-7954. DOI:10.1039/d2sc02291e |

| [36] |

T. Simler, K.N. McCabe, L. Maron, et al., Chem. Sci. 13 (2022) 7449-7461. DOI:10.1039/d2sc01798a |

| [37] |

M.J. Evans, M.D. Anker, C.L. McMullin, et al., Chem. Sci. 13 (2022) 4635-4646. DOI:10.1039/d2sc01064j |

| [38] |

H. Zhang, C.M. Li, X.J. Chen, et al., J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 615 (2022) 110-123. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2022.01.164 |

| [39] |

N. Tsoureas, L. Castro, A.F. Kilpatrick, et al., Chem. Sci. 5 (2014) 3777-3788. DOI:10.1039/C4SC01401D |

| [40] |

B. Fang, L. Zhang, G.H. Hou, et al., Chem. Sci. 6 (2015) 4897-4906. DOI:10.1039/C5SC01684C |

| [41] |

L. Zhang, G.H. Hou, G.F. Zi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 5130-5142. DOI:10.1021/jacs.6b01391 |

| [42] |

L. Chatelain, E. Louyriac, I. Douair, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 337. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-14221-y |

| [43] |

B.L.L. Réant, S.T. Liddle, D.P. Mills, Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 10871-10886. DOI:10.1039/d0sc04655h |

| [44] |

J. Su, T. Cheisson, A. McSkimming, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 13343-13359. DOI:10.1039/d1sc03905a |

| [45] |

D.K. Modder, C.T. Palumbo, I. Douair, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 6153-6158. DOI:10.1039/d1sc00668a |

| [46] |

X.B. Li, Q.Y. Wu, C.Z. Wang, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 125 (2021) 6180-6188. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpca.1c04198 |

| [47] |

X.B. Li, Q.Y. Wu, C.Z. Wang, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 24 (2022) 17782-17791. DOI:10.1039/d2cp01730j |

| [48] |

M.J. Frisch, G.W. Trucks, H.B. Schlegel, et al., Gaussian 16 Software Program, Gaussian Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2016.

|

| [49] |

Q.Y. Wu, C.Z. Wang, J.H. Lan, et al., Inorg. Chem. 53 (2014) 9607-9614. DOI:10.1021/ic501006p |

| [50] |

Q.Y. Wu, J.H. Lan, C.Z. Wang, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 118 (2014) 10273-10280. DOI:10.1021/jp5069945 |

| [51] |

Y. Gong, H.S. Hu, G.X. Tian, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 6885-6888. DOI:10.1002/anie.201302212 |

| [52] |

X.J. Zheng, N. Qu, L.C. Xuan, et al., Int. J. Quantum Chem. 117 (2017) e25378. DOI:10.1002/qua.25378 |

| [53] |

T.R. Yu, Y. Gao, D.X. Xu, et al., Nano Res. 11 (2018) 354-359. DOI:10.1007/s12274-017-1637-9 |

| [54] |

Y.X. Wang, S.X. Hu, L.W. Cheng, et al., CCS Chem. 2 (2020) 425-431. DOI:10.31635/ccschem.020.202000152 |

| [55] |

W. Küchle, M. Dolg, H. Stoll, et al., J. Chem. Phys. 100 (1994) 7535-7542. DOI:10.1063/1.466847 |

| [56] |

X.Y. Cao, M. Dolg, J. Mol. Struct. 673 (2004) 203-209. DOI:10.1016/j.theochem.2003.12.015 |

| [57] |

X.Y. Cao, M. Dolg, H. Stoll, J. Chem. Phys. 118 (2003) 487-496. DOI:10.1063/1.1521431 |

| [58] |

J.P. Yu, K. Liu, Q.Y. Wu, et al., Chin. J. Chem. 39 (2021) 2125-2131. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.202100149 |

| [59] |

T.Y. Xiu, S.M. Zhang, P. Ren, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 108440. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108440 |

| [60] |

R.N. Butler, A.G. Coyne, Chem. Rev. 110 (2010) 6302-6337. DOI:10.1021/cr100162c |

| [61] |

A.V. Marenich, C.J. Cramer, D.G. Truhlar, J. Phys. Chem. B 113 (2009) 6378-6396. DOI:10.1021/jp810292n |

| [62] |

A. Klamt, G. Schüürmann, J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 (1993) 799-805. |

| [63] |

P.G. Allen, D.K. Veirs, S.D. Conradson, et al., Inorg. Chem. 35 (1996) 2841-2845. DOI:10.1021/ic9511231 |

| [64] |

D.Kirk Veirs, C.A. Smith, J.M. Berg, et al., J. Alloys Compd. 213-214 (1994) 328-332. DOI:10.1016/0925-8388(94)90924-5 |

| [65] |

J. Tomasi, B. Mennucci, R. Cammi, Chem. Rev. 105 (2005) 2999-3094. DOI:10.1021/cr9904009 |

| [66] |

W.J. Lai, J.H. Lu, L.H. Jiang, et al., J. Mol. Struct. 1236 (2021) 130300-130307. DOI:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130300 |

| [67] |

M.D. Tissandier, K.A. Cowen, W.Y. Feng, et al., J. Phys. Chem. A 102 (1998) 7787-7794. DOI:10.1021/jp982638r |

| [68] |

W. Tu, S. Zeng, Y. Bai, et al., Ind. Chem. Mater. 1 (2023) 262-270. DOI:10.1039/d2im00041e |

| [69] |

J. Pipek, P.G. Mezey, J. Chem. Phys. 90 (1989) 4916-4926. DOI:10.1063/1.456588 |

| [70] |

T. Lu, F.W. Chen, J. Comput. Chem. 33 (2012) 580-592. DOI:10.1002/jcc.22885 |

| [71] |

P. Lindqvist-Reis, C. Apostolidis, O. Walter, et al., Dalton Trans. 42 (2013) 15275-15279. DOI:10.1039/c3dt51650d |

| [72] |

C. Madic, G.M. Begun, D.E. Hobart, et al., Inorg. Chem. 23 (1984) 1914-1921. DOI:10.1021/ic00181a025 |

| [73] |

P.J. Hay, R.L. Martin, G. Schreckenbach, J. Phys. Chem. A 104 (2000) 6259-6270. DOI:10.1021/jp000519h |

| [74] |

S.D. Conradson, K.D. Abney, B.D. Begg, et al., Inorg. Chem. 43 (2004) 116-131. DOI:10.1021/ic0346477 |

| [75] |

A.M. Lines, S.R. Adami, S.I. Sinkov, et al., Anal. Chem. 89 (2017) 9354-9359. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02161 |

| [76] |

A.J. Bard, T.V. Atkinson, J. Phys. Chem. 75 (1971) 2043-2048. DOI:10.1021/j100682a023 |

| [77] |

J.Q. Adams, J.R. Thomas, J. Chem. Phys. 39 (1963) 1904-1906. DOI:10.1063/1.1734558 |

| [78] |

P. Smith, R.D. Stevens, R.A. Kaba, J. Phys. Chem. 75 (1971) 2048-2055. DOI:10.1021/j100682a024 |

| [79] |

K.R. Gorantla, B.S. Mallik, J. Phys. Chem. A 126 (2022) 3301-3310. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpca.2c01043 |

| [80] |

J.G. Muller, R.P. Hickerson, R.J. Perez, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 119 (1997) 1501-1506. DOI:10.1021/ja963701y |

| [81] |

R.S. Miller, J.M. Sealy, M. Shabangi, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122 (2000) 7718-7722. DOI:10.1021/ja001260j |

| [82] |

Y.M. Lee, S. Kim, K. Ohkubo, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 2614-2622. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b12935 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35