b School of Materials Science & Engineering, PCFM Lab, School of Chemistry, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510275, China;

c School of Chemical Engineering and Light Industry, Guangdong University of Technology, Guangzhou 510006, China

Methanol is a less toxic, cheap and abundant chemical, which has shown great potential in organic transformations and energy technologies. In particular, methanol has emerged as an appealing methylation agent based on the borrowing hydrogen (BH), or hydrogen auto-transfer (HA) approach [1–4]. Compared to conventional methylation reagents such as Grignard reagents, methyl iodide and methyl sulfate, methanol is more green, sustainable and less toxic. It allows the formation of various C-Me or N-Me groups through the reaction of methanol with N or C-nucleophiles, respectively. In addition, methanol is also an excellent hydrogen carrier (ca. 12.5 wt% hydrogen), which has been used for the transfer hydrogenation (TH) of unsaturated bonds [5]. A wide range of substrates such as ketones, aldehydes, olefins, and alkynes could be readily reduced though transfer hydrogenation, using MeOH as the hydrogen source.

Recently, significant efforts have been devoted to the transformation of ketones with methanol. Though transfer hydrogenation, the ketones could be reduced to secondary alcohols (Scheme 1a). For examples, Sundararaju et al. demonstrated a Cp*Ir(Ⅲ) complex with 6,6′-hydroxyl-2,2′-bipyridyl ligand for transfer hydrogenation of ketones using methanol [6]. In 2020, Li et al. also reported the [Cp*Ir(2,2′-bpyO)(OH)][Na] complex for transfer hydrogenation of ketones with methanol [7]. Later, such transformation was achieved by Bagh et al. as well using a Ru-triazole complex [8].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. The transformation of ketones with methanol and challenges. | |

In addition, ketones could also be converted to α-methylated ketones with methanol as a C1 source through the BH or HA approach. Over the past decades, the groups of Donohoe [9,10], Obora [11], Andersson [12], Morrill [13], Sortais [14], and others [15–17], have developed varieties of transition metal complexes for the synthesis of α-methylated ketones (Scheme 1b). For example, Liu's group and Morril's group independently developed the cobalt [15] and iron [13]-based catalysts for the α-methylation of ketones with methanol. Later, Sortais et al. reported a PN3P-Mn complex catalyzed the α-methylation of ketones with methanol [14]. Although the amount of methanol is significantly excessive in these reactions, the further transfer hydrogenation of α-methylated ketones to the β-methylated secondary alcohols is very rare. In 2022, Xing and Wang et al. reported the synthesis of β-methylated secondary alcohols from non-methylated ketones with methanol utilizing a Cp*Ir complex [18]. However, this catalytic system requires two consecutive processes, and is only applicable to non-methylated ketones. While preparing this article, Kundu et al. reported a cyclometalated (NNC)Ru(Ⅱ) complex, which catalyzed the selective functionalization of ketones with methanol [19]. In these transformations, different products could be obtained from the reaction of ketones with methanol, involving several pathways, such as transfer hydrogenation, α-methylation, and α-methylation/transfer hydrogenation (Scheme 1c). However, it is still a great challenge to control the selectivity for transfer hydrogenation and methylation using a single catalyst.

Herein, we report the pincer-type NHC-Ru complex, which is a promising catalyst for the selective transformation of ketones with methanol (Scheme 1d). They are significant because (1) we realize the base-controlled selectivity for transfer hydrogenation and methylation; (2) we provide a green way to the transfer hydrogenation of ketones using methanol; (3) the synthesis of β-methylated secondary alcohols is now accessible; (4) the conditions are mild, and weak bases are used.

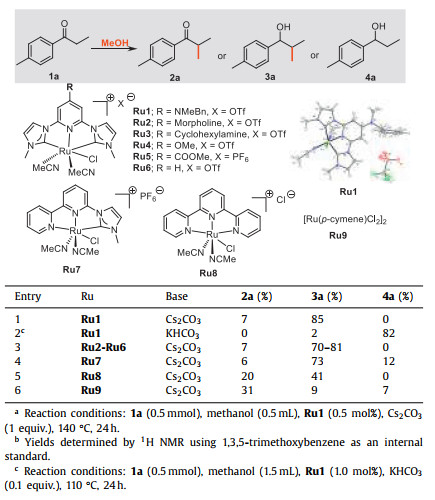

We investigated the transformation of 4′-methylpropiophenone (1a) with methanol in the presence of a pyridyl-based CNC ligand-stabilized Ru complex (Ru1) and observed a base-dependent product formation (Table 1 and Table S5 in Supporting information). When the Cs2CO3 (entry 1) is used as a base, the α-methylation/transfer hydrogenation pathway is preferred, and 85% yield of the β-methylated secondary alcohol 3a was obtained with a great selectivity (2a: 3a: 4a = 7:85:0). While 82% yield of 4a with a great selectivity (2a: 3a: 4a = 0:2:82) was achieved though the transfer hydrogenation pathway, with KHCO3 as a base (entry 2). Then, a library of Ru complexes (Ru2-Ru9) was tested to investigate the effect of the structure of the catalyst on catalytic activity [20]. Ru2-Ru6 bearing different R groups (R = NR1R2, OMe, COOCH3, H) attached to the pyridyl ring, and Ru7 with bipyridyl-based NNC ligand, were found to be slightly less reactive compared to Ru1 (entries 3 and 4). The tris-bipyridyl-based NNN complex Ru8 and [Ru(p-cymene)Cl2]2 (Ru9), displayed much inferior activity compared to Ru1 (entries 5 and 6). In the absence of the Ru complex or base, no products were observed in the control experiments (Table S7, entries 9 and 10).

|

|

Table 1 Selected data for the screening of the optimal conditions.a,b,c |

Using the optimized conditions, we investigated the substrate scope for the selective synthesis of β-methylated secondary alcohols (Scheme 2). The propiophenone derivatives containing electron donating groups like methoxy and methyl gave the corresponding products 3a and 3b, and 3e-3f in good to excellent yields (76%–96%). However, substrates bearing electron-withdrawing groups (-CF3 and -Cl) exhibited relatively poor yields (3c and 3d). In the case of 4′-fluoropropiophenone, the fluorine group was converted to the methoxy group and furnished the product 3b in 56% yield. Sterically hindered 2′-methylpropiophenone and heteroaromatic 2-propionylpyridine were compatible, and generated 3g and 3h in 66% and 65% yields, respectively. The α-alkyl (Et, n-Pr, Bn), and α-phenyl substituted acetophenone derivatives undergo efficient methylation in excellent yields (3i−3l, 71%−80%). Moreover, acetophenone derivatives such as 4′-methoxyacetophenone and 2-acetonaphthone provided the di-methylated products 3b and 3m in 68% and 70% yields, respectively. For the sterically hindered 2,6-di-methyl acetophenone, the carbonyl group has not been reduced and the α-methylated ketone 3n was obtained in 79% yield. Notably, the α, β-unsaturated ketone trans-chalcone was also well tolerated and furnished the product 3k in 62% yield. When CD3OD was used, a β-CD3 group and significant deuterium incorporation at the α- and β-positions were found in the products 3a-d and 3b-d. Interestingly, we also observed H/D exchange for substrate with benzylic position (3a-d) [17]. In the case of 4′-methoxyacetophenone, the doubly deuteromethylated product 3b-d2 was obtained in 43% yields. These results indicated that methanol is the source of the methyl group and the hydrogen source.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Substrate scope for the synthesis of β-methylated secondary alcohols. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.5 mmol), methanol (0.5 mL), Ru1 (0.5 mol%), Cs2CO3 (1 equiv.), 140 ℃, 24 h. a CD3OD (0.5 mL) was used. | |

Next, we also explored the scope of the transfer hydrogenation of ketones using methanol (Scheme 3). Propiophenone derivatives bearing either electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents were selectively reduced to afford the corresponding products 4a–4h in 57%–94% yields. In this transformation, the halogen substituents such as fluorine or chlorine, and F3C-group were well tolerated, and yielded the corresponding products 4c–4e and 4h in good yields. Even sterically hindered 2′-methylpropiophenone could smoothly convert to the corresponding product 4i in 67% yield. The α-substituted acetophenones like butyrophenone, valerophenone, 3-phenylpropiophenone, and 2-phenylacetophenone afforded the desired products 4j–4m in 56%−91% yields. Cyclic ketone α-tetralone and heteroaromatic 3-acetylpyridine were compatible, and the corresponding products 4n and 4q were isolated in 54% and 30% yields, respectively. Furthermore, 4′-methoxyacetophenone and 2-acetonaphthone were also found to be active enough to yield the corresponding products 4o and 4p in 60% and 82% yields, respectively. Notably, 4′-methylphenylacetone reacted efficiently with methanol to produce the β-methylated secondary alcohol 4r in 80% yield. Aliphatic ketones, such as cyclooctanone and 2-dodecanone, showed high reactivities, achieving the corresponding products 4s and 4t in 61% and 78% yields, respectively. Again, the transfer hydrogenation proceeded well when CD3OD was used, and significant deuterium incorporation at the α- and β-positions were found in the products 4a-d, 4b-d, 4o-d, and 4p-d.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Substrate Scope for the transfer hydrogenation of ketones using methanol. Reaction conditions: 1 (0.5 mmol), methanol (1.5 mL), Ru1 (1.0 mol%), KHCO3 (0.1 equiv.), 110 ℃, 24 h. a CD3OD (1.5 mL) was used. | |

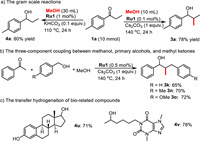

To explore the synthetic potentials of our protocol, gram-scale reactions, and several synthetic application experiments were carried out (Scheme 4). With 1a as a substrate in 10 mmol scale reactions, products 3a and 4a were obtained in 78% and 80% yields, respectively (Scheme 4a). Delightfully, the loading of Ru1 could be reduced to 0.1 mol% for the gram-scale synthesis of 3a. Additionally, this protocol worked smoothly in three-component coupling between methanol, primary alcohols, and methyl ketones. Moderate to good yields of doubly alkylated products 3k, 3n, and 3o were obtained in this one-pot process (Scheme 4b). Moreover, the developed method was also successfully applied for the transfer hydrogenation of bio-related compounds such as estrone and pentoxifylline (4u and 4v, Scheme 4c).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 4. Gram-scale reactions and synthetic application. | |

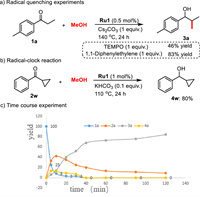

In order to gain mechanistic insight, we performed a series of control experiments and kinetic experiments. Firstly, the effect of the base on the reaction selectivity was studied. The strong bases such as KOtBu, KOH, NaOtBu, NaOH, and Cs2CO3 are more prone to the aldol condensation, resulting the product 3a as a major product. The weak bases such as KHCO3, K2CO3, NaHCO3, and Na2CO3 cannot promote the methylation step, and transfer hydrogenation product 4a was obtained as a major product. In the presence of radical scavengers such as TEMPO and 1,1-diphenylethylene, product 3a was obtained in 46% and 83% yields, respectively (Scheme 5a). Additionally, a radical clock substrate, cyclopropyl phenyl ketone, offered the product 4w in 80% yield (Scheme 5b). Therefore, the radical pathway could be ruled out in this transformation [21]. A parallel experiment revealed a kH/kD value of 1.09 (Fig. S1 in Supporting information), indicating that the activation of methanol may not be involved in the rate-determining step (RDS). Furthermore, a time course experiment (Scheme 5c, Fig. S2 in Supporting information) using 1a and MeOH to form the 3a was carried out to gain further information about the mechanism [22]. We found that the progress of the reaction was very rapid during the initial period; almost 52% of 1a was converted to both 2a (33%), 3a (6%), and 4a (13%) after 5 min. After that, there was a gradual increase of 3a with the corresponding depletion of 2a and 4a, which supports the tandem α-methylation/transfer hydrogenation steps. Subsequently, kinetic studies (Figs. S3 and S4 in Supporting information) suggested a zero-order dependence on the concentration of ketone 1a, and a first-order dependence on the concentration of Ru catalyst.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 5. Preliminary mechanistic studies. | |

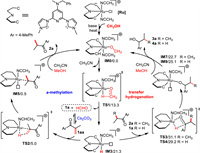

Based on the above results and literature precedents [16,18,23,24], two catalytic cycles for the α-methylation/transfer hydrogenation and transfer hydrogenation and its results of DFT calculations were depicted in Scheme 6. Both cycles are initiated by the base-mediated activation of the compound Ru1 afforded the alkoxo complex IM0, from which dissociation of acetonitrile ligand provided the corresponding intermediate IM1 (10.5 kcal/mol, Scheme S4 in Supporting information). Next, β-hydrogen elimination through transition state TS1 (13.3 kcal/mol) generated the ruthenium hydride species IM3 (21.3 kcal/mol). For the α-methylation steps, the aldol condensation undergoes in the presence of Cs2CO3, which produces the α, β-unsaturated ketones 1aa. Afterward, the C=C bond of 1aa was reduced via TS2 (5.0 kcal/mol), giving the intermediate 2a. For the transfer hydrogenation steps, the C=O bond of intermediate 2a or 1a was reduced through transition state TS3 (31.1 kcal/mol) or TS4 (29.2 kcal/mol) to give the alcohol product 3a or 4a, respectively. The low free energy barrier of the methanol dehydrogenation steps (TS1, 13.3 kcal/mol) suggests that alcohol dehydrogenation is not the RDS, which is in line with the results of the observed KIE values. A facile C=C bond hydrogenation step (TS2, 5.0 kcal/mol) was consistent with the time course experiments that 33% of 2a was detected after 5 min.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 6. Plausible reaction pathways. Free energies are given in kcal/mol. | |

In conclusion, we developed highly chemoselective and efficient NHC-Ru-catalyzed tandem α-methylation/transfer hydrogenation or transfer hydrogenation of ketones using methanol. A wide range of ketones bearing different functional groups were well tolerated. In this protocol, two different kinds of secondary alcohols including the deuterated alcohols were chemoselectively synthesized by simply changing the base. Moreover, this process was also successfully extended to the bio-related molecules, and the three-component coupling between methyl ketones, primary alcohols, and methanol. Experiment and DFT mechanistic investigations revealed that this catalyst system follows the α-methylation/transfer hydrogenation or transfer hydrogenation mechanism.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Nos. 22002023, 21973113, 21977019), the Guangdong Natural Science Funds for Distin-guished Young Scholar (No. 2015A030306027), the Tip-top Youth Talents of Guangdong special support program (No. 20153100042090537) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109323.

| [1] |

M. Liu, L. Xu, Y. Wei, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1559-1562. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.019 |

| [2] |

V. Goyal, N. Sarki, A. Narani, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 474 (2023) 214827. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214827 |

| [3] |

P.Mehara Sheetal, P. Das, Coord. Chem. Rev. 475 (2023) 214851. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214851 |

| [4] |

J. Guo, J. Tang, H. Xi, S.Y. Zhao, W. Liu, Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107731. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.08.011 |

| [5] |

N. Garg, A. Sarkar, B. Sundararaju, Coord. Chem. Rev. 433 (2021) 213728. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2020.213728 |

| [6] |

Z. Chen, G. Chen, A.H. Aboo, J. Iggo, J. Xiao, Asian J. Org. Chem. 9 (2020) 1174-1178. DOI:10.1002/ajoc.202000241 |

| [7] |

R. Wang, X. Han, J. Xu, P. Liu, F. Li, J. Org. Chem. 85 (2020) 2242-2249. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.9b02957 |

| [8] |

R. Ghosh, N.C. Jana, S. Panda, B. Bagh, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 9 (2021) 4903-4914. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c00633 |

| [9] |

L.K. Chan, D.L. Poole, D. Shen, M.P. Healy, T.J. Donohoe, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 761-765. DOI:10.1002/anie.201307950 |

| [10] |

D. Shen, D.L. Poole, C.C. Shotton, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 1642-1645. DOI:10.1002/anie.201410391 |

| [11] |

S. Ogawa, Y. Obora, Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 2491-2493. DOI:10.1039/C3CC49626K |

| [12] |

X. Quan, S. Kerdphon, P.G. Andersson, Chem. Eur. J. 21 (2015) 3576-3579. DOI:10.1002/chem.201405990 |

| [13] |

K. Polidano, B.D.W. Allen, J.M.J. Williams, L.C. Morrill, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 6440-6445. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b02158 |

| [14] |

A. Bruneau-Voisine, L. Pallova, S. Bastin, V. Cesar, J.B. Sortais, Chem. Commun. 55 (2019) 314-317. DOI:10.1039/c8cc08064j |

| [15] |

Z. Liu, Z. Yang, X. Yu, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 5228-5231. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02462 |

| [16] |

K. Chakrabarti, M. Maji, D. Panja, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 4750-4753. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02105 |

| [17] |

J. Sklyaruk, J.C. Borghs, O. El-Sepelgy, M. Rueping, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 775-779. DOI:10.1002/anie.201810885 |

| [18] |

A. Song, S. Liu, M. Wang, et al., J. Catal. 407 (2022) 90-96. DOI:10.1016/j.jcat.2022.01.021 |

| [19] |

K. Ganguli, A. Mandal, M. Pradhan, A.K. Deval, S. Kundu, ACS Catal. 13 (2023) 7637-7649. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.3c01097 |

| [20] |

C. Huang, J. Liu, H.H. Huang, X. Xu, Z. Ke, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 262-265. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.06.046 |

| [21] |

A.K. Bains, A. Biswas, D. Adhikari, Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 15442-15445. DOI:10.1039/d0cc07169b |

| [22] |

J. Tang, J. He, S.Y. Zhao, W. Liu, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202215882. DOI:10.1002/anie.202215882 |

| [23] |

B. Paul, S. Shee, D. Panja, K. Chakrabarti, S. Kundu, ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 2890-2896. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b00021 |

| [24] |

S. Shee, B. Paul, D. Panja, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 359 (2017) 3888-3893. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201700722 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35