b State Key Laboratory of Pollution Control and Resource Reuse, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tongji University, Shanghai 200092, China

Due to its effectiveness in treating respiratory diseases in domestic animals, FLO has become a widely used antibiotic in countries such as China, Brazil, and the United States [1]. However, its stable ring structure and high bond energy of the C—Cl bond (340.2 kJ/mol) make it difficult to effectively eliminate using conventional water treatment processes [2]. Recent studies have also shown that the accumulation of antibiotics, including FLO, in the environment can lead to adverse effects on human health through various pathways [1,3]. As a result, there is an urgent need to develop innovative and effective strategies to address the challenges posed by FLO-contaminated water.

Zero-valent iron (ZVI), a common transition metal, is widely recognized as a promising material in environmental remediation due to its eco-friendliness, abundance, and cost-effectiveness [4,5]. Previous studies have demonstrated that ZVI is effective in reducing many halogenate organic pollutants, in which ZVI mainly serve as a mild reductant [6]. Meanwhile, ZVI can also act as an efficient activator for H2O2, O2 and peroxymonosulfate [7]. For example, Zhang et al. [8] and Sedlak et al. [9] have revealed that organic pollutants can be deeply oxidized by the generated reactive oxygen species (ROSs) through the ZVI-activated molecular oxygen. Although ZVI offers numerous advantages for remediating environmental organic pollutants in water, passivation and agglomeration remain significant challenges [10]. Consequently, several strategies have been proposed to prolong its lifetime, including acid washing [11], sulfidation [12], and the synthesis of ZVI composites [13], etc. Among them, supported ZVI with other carriers has become one of the most commonly used methods to stabilize and disperse those ZVI, due to its easy operation and high efficiency [13].

The selection of carriers was a crucial factor affecting the performance of synthesized ZVI-based composites. Various supports have been demonstrated to be effective in reducing the agglomeration of ZVI, which can be mainly classified into organic and inorganic ones. Organic carriers, such as carboxymethyl cellulose (CMS) [14], poly acrylic acid (PAA) [15], and high-density polyethylene (HDPE) [16], have been used as stabilizers for ZVI nanoparticles, resulting in improved stability and reactivity. However, these organic supports often adsorb impurities and compete with reactive species for target pollutants, reducing the reactivity of organic-supported ZVI [17]. In contrast, inorganic supports, such as biochar [18], zeolite, bentonite, and MoS2, offer more advantages in improving the reuse performance of ZVI. For instance, in the work of Xu et al., biochar-supported nZVI and S-nZVI were synthesized, revealing that the significantly enhanced reactivity is attributed to the improved dispersion of S-nZVI on the treated biochar [19]. Recently, silicon carbide (SiC) has been considered a promising carrier for ZVI due to its semi-conductive property and high mechanical strength [4]. It was found that SiC-ZVI/PMS exhibited a 4-fold increase in degradation rates of FLO compared to ZVI/PMS. However, as SiC is an extremely stable ceramic material, the enhancement mechanism of SiC for ZVI has not been clearly investigated. Moreover, as a common halogenated antibiotic, FLO can theoretically be reduced through the dehalogenation pathway. Nevertheless, the direct reduction of FLO by SiC/ZVI has not been explored. Therefore, it is still necessary to investigate the enhancement mechanism of SiC for ZVI and the degradation pathway of FLO.

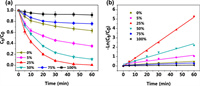

In this study, ZVI/SiC composite was synthesized using a planetary ball-milling technique and employed for the degradation of FLO. As can be seen in Fig. S1 (Supporting information), the kinks resembling structures found on the surface of ZVI/SiC composites were primarily generated through successive cycles of welding, fracturing, and re-welding during the high-energy milling process. This led to the interweaving of the tougher SiC particles with the more malleable ZVI particles. The ZVI/SiC composites with various mass percentages of SiC (including 0%, 5%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%) were prepared to evaluate their effect on FLO elimination. As depicted in Figs. 1a and b, the degradation efficiency of FLO by ZVI/SiC increased to nearly 100% as the percentage of SiC rose from 0% to 25%; however, it decreased as the percentage of SiC continued to increase. Pure SiC removed only 8.14% of FLO after one hour of reaction, which was most likely caused by surface absorption rather than degradation. These results clearly suggest that supporting ZVI with an appropriate amount of SiC could enhance its reactivity toward the degradation of FLO.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Influencing of SiC/ZVI ratio for the degradation of FLO by ZVI/SiC system (a), and its degradation kinetics (b). Experimental condition: 20 mg/L FLO, 5 g/L ZVI/SiC, pH0 = 3. | |

In order to investigate the underlying influencing mechanism of SiC, Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET), X-Ray Diffraction (XRD), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS), and VSM characterizations were initially used to compare the physicochemical properties of ZVI/SiC and ZVI. As shown in Fig. S2 (Supporting information), the BET surface area of ZVI/SiC is 8.2 times higher than that of pure ZVI, which could provide more active sites for the degradation of FLO. This increased surface area may result from the better dispersion of ZVI particles due to the use of SiC support. As depicted in Fig. 2a, the VSM curve demonstrates that the magnetic intensity of ZVI/SiC is lower than that of pure ZVI. Stronger magnetism makes it easier for iron particles to reunite. The lower magnetic intensity of ZVI/SiC suggests that SiC can alleviate the agglomeration of iron particles [20]. Meanwhile, the impact of SiC ratio on the surface species of ZVI was calculated by fitting the XPS results. As shown in Fig. 2b, there is a notable shift in the composition of Fe0 and Fe2+ species with increasing SiC content from 0% to 50%. However, this trend reverses as the SiC content further increases from 50% to 75%. It is worth noting that the reactivity of Fe species significantly depends on their oxidation state, with Fe0 and Fe2+ being more reactive than Fe3+ [21]. Interestingly, even though the Fe2+ and Fe0 ratio surpasses that of the 25% mark when SiC comprises 50% of the composition, the degradation rate of FLO demonstrates a decline. This phenomenon can be attributed to the fact that an excessive SiC dose might actually lead to a reduction in the degradation rate of FLO. This occurs due to the nature of ZVI acting as the paramount electron donor; an excessive abundance of ZVI could create an oversaturation of active sites, causing a counterintuitive decrease in degradation efficiency. This insight aligns with the observation of reduced peak intensities across all iron species as SiC ratio increases in the XRD pattern (as depicted in Fig. 2c) [22].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) VSM results of ZVI and ZVI/SiC. (b) The proportion of iron species with different valences on ZVI/SiC (with different SiC mass percent) obtained from XPS results. (c) XRD pattern of ZVI and ZVI/SiC. And electrochemical characterization of ZVI and ZVI/SiC: (d) Cyclic voltammogram, (e) Tafel polarization curve, (f) Linear scanning voltammetry curve. | |

Furthermore, cyclic voltammetry (CV), linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), and Tafel curves were employed to better understand the influence mechanism of SiC on ZVI. As shown in the CV in Fig. 2d, the introduction of SiC led to a significant increase in the current intensity of ZVI. This indicated that the electron transfer in the ZVI/SiC system is faster than that of ZVI, suggesting that ZVI/SiC is more reactive than ZVI. Results from the Tafel curve further verified this suggestion, as the observed corrosion currents (Icorr) of ZVI/SiC were nearly 5 times higher than those of pure ZVI (Fig. 2e). Moreover, the hydrogen evolution potential (HEP) of ZVI/SiC and pure ZVI were compared using LSV (Fig. 2f). It was observed that the HEP of ZVI/SiC was significantly lower than that of ZVI, implying that ZVI/SiC had a stronger reducing ability than bare ZVI [3]. All these results demonstrated that the use of SiC support could accelerate the electron transfer rate and enhance the reduction ability of ZVI.

Two factors of initial pH value and catalyst dosage were selected to assess their impact on the degradation of FLO by ZVI/SiC. As shown in Fig. S3a (Supporting information), FLO could be degraded within one hour at a wide pH range by ZVI/SiC. The Kobs of FLO decreased from 0.111 min−1 to 0.056 min−1 as the initial pH value increased from 3 to 9 (Fig. S3b in Supporting information). Previous studies suggested that an acidic environment could alleviate the passivation of iron oxides and, subsequently, enhance the degradation of FLO [23]. These results were consistent with previous suggestions.

Figs. S3c and d (Supporting information) illustrates the impact of different catalyst dosages on the degradation of FLO by ZVI/SiC. As can be seen, both the degradation efficiency and the Kobs increased with the increasing ZVI/SiC dose. When the dose of ZVI/SiC was increased from 0.5 g/L to 10 g/L, FLO degradation efficiency dramatically improved from 14.6% to 100%. However, when the dose of ZVI/SiC was further increased to 20 g/L, this increase became smaller. A higher catalyst dosage can provide a larger number of active sites, so the degradation efficiency of FLO continued to increase with the increasing ZVI/SiC dose [24]. Nonetheless, it is not economical when the dosage of ZVI/SiC is too high, as ineffective consumption could become much more severe.

The degradation intermediates were analyzed using UPLC-MS/MS to investigate the possible degradation pathways of FLO by ZVI/SiC. As shown in Table S1 (Supporting information), a total of 7 intermediates were identified based on the MS analysis and previous literatures [25], namely TP229, TP247, TP271, TP279, TP289, TP337, TP339, with corresponding molecular formulas of C10H12NO2FS, C10H14O3NFS, C12H15NO3FS, C11H12Cl2FNO2, C12H16NO4FS, C12H13NO4SCl2, C12H12NO3FSCl2, respectively. Among them, TP247 and TP289, with two chlorine atoms removed, were the main intermediates. The concentration of Cl− increased as the FLO concentration decreased, achieving an 81.4% chloride mass balance if two Cl− were removed from FLO (Fig. 3a). Moreover, the remove of FLO was not affected by the addition of 1 mmol/L to 100 mmol/L TBA (a quenching agent for hydroxyl radicals (•OH)) (Fig. 3b, details of the degradation kinetics of FLO by ZVI/SiC with different TBA concentration were shown in Fig. S4 in Supporting information), as well as anoxic condition (Fig. 3c). This ruled out the •OH-mediated oxidation of FLO, as previous studies reported that iron-based systems can generate •OH through the activation of O2 [25–27]. These results suggest that FLO was primarily degraded through the reductive dechlorination process. To investigate this speculation, semi-quantification results of different FLO degradation products were introduced to comprehensively evaluate changes in the overall toxicity of the products. As depicted in Fig. 4a, the relative abundance of TP339 and TP247 initially peaked at around the 5-min mark, then subsequently decreased throughout the degradation process. Concurrently, the relative abundance of TP289 and TP271 displayed a gradual increment. These findings imply that FLO primarily transforms into TP339, which subsequently converts into TP289, TP271 and TP247, eventually undergoing hydrolysis to form TP229. It is noteworthy that each of these transformations involves reductive dechlorination, with the simultaneous removal of two chlorine atoms. Furthermore, Fig. 3c illustrates that dechlorination predominantly occurs during the initial half of the one-hour reaction period. This research underscores the significance of ZVI in the reduction of chlorinated organic compounds, traditionally conceived in terms of the dechlorination process. However, our study revealed that dehydration and deacetylation also contribute to the degradation of FLO, in addition to dechlorination. Indeed, both processes-dichlorination and deacetylation can be classified as hydrogenolysis reactions. In this context, active hydrogen (H*) assumes a significant role as a potent reductive agent, effectively promoting the degradation of pollutants by cleaving the σ bond. This introduces an innovative mechanism for the reductive dechlorination of chlorinated organics by ZVI [28–30].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Quantification of Cl− and F− in the dehalogenation of FLO by ZVI/SiC. (b) Effects of TBA on FLO degradation with different concentration. (c) The degradation of FLO in different oxygen environments. Experimental condition: 20 mg/L FLO, 5 g/L ZVI/SiC, pH0 = 3. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) The concentration of FLO and its products over time. (b) The lethal concentration of 50% and chronic toxicity of FLO and its degradation products for fish by ECOSAR program. | |

Drawing on the preceding discussion and the predicted intermediates, six degradation pathways of FLO are delineated in Fig. S5 (Supporting information) [27]. Pathway Ⅰ encompass the dechlorination of FLO to TP279. In Pathway Ⅱ, FLO initially undergoes dechlorination to TP289, subsequently followed by hydrolysis to TP247 (or alternatively, direct amide hydrolysis of FLO to TP247), and culminates in dehydration to TP229. In Pathway Ⅲ, TP289 is subject to consecutive dehydration and hydrolysis steps, resulting in TP271 and TP229. Pathway Ⅳ entails the dehydration of FLO to TP339, which can then either transform into TP289 through dechlorination and hydroxylation or convert into TP271 through dechlorination, eventually being hydrolyzed to TP229. Lastly, Pathway Ⅵ initiates the defluorination of FLO to TP337.

Moreover, the biological toxicity of FLO and its degradation intermediates were evaluated using Escherichia coli DH5α and the ECOSAR program [3,31]. As depicted in Figs. S6a and b (Supporting information), the growth of E. coli DH5α cultivated in the degradation products was significantly higher than that cultivated in the parent FLO solution, suggesting a remarkable reduction in the biological toxicity after degradation. The results of the ECOSAR program were consistent with the above findings, as shown in Fig. 4b. However, there is a possibility that the toxicity of some intermediates may increase, as the ChV and EC50 values of TP339 for green algae increased. Future investigations should pay more attention to this issue.

The reusability and potential applicability of ZVI/SiC in remediating FLO-contaminated wastewater were investigated in this study. The cycling experiments demonstrated that ZVI/SiC was much more efficient when consecutively used, achieving a removal efficiency of nearly 90% after four cycles, while pure ZVI could only achieve a degradation efficiency of 17.0% (Fig. 5a). Additionally, ZVI/SiC achieved high removal efficiency (> 97.0%) in complex water matrices, including surface water and artificial wastewater, within an hour, despite slightly reduced reactivity. The Kobs in these water matrices were 0.0577 min−1, 0.0922 min−1, and 0.0873 min−1 for surface water, artificial wastewater, and DI water, respectively (Fig. 5b). This result indicated the great potential of ZVI/SiC for remediating FLO-contaminated wastewater.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Stability of ZVI/SiC and ZVI for FLO degradation. (b) Application of ZVI/SiC system for FLO-contaminated water. Experimental condition: 20 mg/L FLO, 5 g/L ZVI/SiC, pH0 = 3. | |

In general, this study represents one of the first comprehensive investigations into the influence of SiC on ZVI for the remediation of environmental pollutants. The incorporation of SiC at a mass percentage of 25% with ZVI resulted in a remarkable 12.5-fold increase in FLO removal rates. Results demonstrated that using SiC support reduces the magnetic intensity of ZVI, alleviates iron particle agglomeration, and accelerates electron transfer rates, thus enhancing the degradation performance for FLO. Furthermore, toxicity assessment using E. coli DH5α and the ECOSAR program indicated that biological toxicity was significantly reduced after the degradation reaction. FLO was suggested to primarily degrade through reductive dechlorination, and its degradation pathway was proposed. When used consecutively, ZVI/SiC achieved a removal efficiency of nearly 90% after four cycles and exhibited high removal efficiency in both FLO-contaminated surface water and artificial wastewater. These results suggest that ZVI/SiC composites hold significant potential for field applications in remediating chlorinated organic pollutants. This study also presents an alternative approach for preparing highly active iron-based materials, in addition to nano-zero valent and iron-based bimetals. Consequently, this study contributes new insights into the design of highly active ZVI-based systems for environmental remediation.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was financially supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2021A1515110954), National Key Research and Development Projects of China (No. 2022YEC3203302), Guangdong Province Enterprise Science and Technology Commissioner Project (No. GDKTP2021048000), and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41907292).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109385.

| [1] |

F. Yang, F. Yang, G. Wang, et al., Aquaculture 515 (2020) 734542. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734542 |

| [2] |

W. Jiang, X. Xia, J. Han, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 52 (2018) 9972-9982. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b01894 |

| [3] |

J. Xu, P. Wang, S. Chen, et al., J. Environ. Sci. 137 (2024) 420-431. DOI:10.3390/jpm14040420 |

| [4] |

Y. Zhang, C. Zhang, Y. Liu, et al., Sep. Purif. Technol. 303 (2022) 122187. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2022.122187 |

| [5] |

X. Jin, L. Yang, H. Li, et al., Environ. Pollut. 331 (2023) 121866. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121866 |

| [6] |

C. Wang, W. Zhang, Commun. Res. 31 (1997) 2154-2156. |

| [7] |

C. Ling, S. Wu, T. Dong, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 423 (2022) 127082. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127082 |

| [8] |

Z. Ai, Z. Gao, L. Zhang, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 47 (2013) 5344-5352. DOI:10.1021/es4005202 |

| [9] |

C.R. Keenan, D.L. Sedlak, Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 (2008) 6936-6941. DOI:10.1021/es801438f |

| [10] |

S. Wu, S. Cai, F. Qin, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 446 (2023) 130730. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.130730 |

| [11] |

W. Han, F. Fu, Z. Cheng, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 302 (2016) 437-446. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.09.041 |

| [12] |

L. Liang, X. Li, Y. Guo, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 404 (2021) 124057. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124057 |

| [13] |

F. Meng, J. Xu, H. Dai, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 56 (2022) 4489-4497. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.1c08671 |

| [14] |

H. Zhou, J. Han, S.A. Baig, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 198 (2011) 7-12. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.10.002 |

| [15] |

L.L.S. Silva, W. Abdelraheem, M.N. Nadagouda, et al., J. Membrane Sci. 620 (2021) 118817. DOI:10.1016/j.memsci.2020.118817 |

| [16] |

Y. Shi, T. Liu, S. Chen, et al., Biochem. Eng. J. 177 (2022) 108226. DOI:10.1016/j.bej.2021.108226 |

| [17] |

P.N. Angnunavuri, F. Attiogbe, B. Mensah, Sci. Total. Environ. 845 (2022) 157347. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157347 |

| [18] |

Z. Li, Y. Sun, Y. Yang, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 383 (2020) 121240. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.121240 |

| [19] |

J. Xu, Z. Cao, Y. Wang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 359 (2019) 713-722. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2018.11.180 |

| [20] |

Y.W. Liu, M.X. Guan, L. Feng, et al., Nanotechnology 24 (2012) 025604. |

| [21] |

D. Li, Y. Zhong, H. Wang, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 759 (2021) 143481. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143481 |

| [22] |

J. Xu, H. Li, G.V. Lowry, Acc. Mater. Res. 2 (2021) 420-431. DOI:10.1021/accountsmr.1c00037 |

| [23] |

L. Liu, X. Xu, Y. Li, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 382 (2020) 122780. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122780 |

| [24] |

W. An, H. Wang, T. Yang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 451 (2023) 138653. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2022.138653 |

| [25] |

M. Qiu, A. Hu, Y.M. Huang, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 403 (2021) 123974. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123974 |

| [26] |

R. Sun, J. Yang, R. Huang, et al., Chemosphere 303 (2022) 135123. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.135123 |

| [27] |

W. Xie, S. Yuan, M. Tong, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 54 (2020) 2975-2984. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.9b04870 |

| [28] |

Z. Cao, H. Li, G.V. Lowry, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 55 (2021) 2628-2638. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.0c07319 |

| [29] |

Z. Cao, J. Xu, H. Li, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 400 (2020) 125813. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125813 |

| [30] |

Z. Cao, X. Liu, J. Xu, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 51 (2017) 11269-11277. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.7b02480 |

| [31] |

N. Wang, L. He, X. Sun, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 427 (2022) 127941. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127941 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35