b School of Life Science, Jinggangshan University, Ji’an 343009, China

The accumulation of the heavy metal Pb(Ⅱ) absorbed by the body with water negatively affect the human life and health, leading to serious damage to the nervous and circulatory system, etc. [1–3]. The removal of Pb(Ⅱ) from wastewater to ensure water security is of weighty importance for sustainable social development. Nowadays, adsorption as one of the diversified methods to remove heavy metals from wastewater is extensively used for the treatment of Pb(Ⅱ) in effluent due to its convenient operation, low cost and less pollution [4]. Traditional adsorbents such as activated carbon are limited in adsorption capacity and hydrophobicity owing to their pore structure [5,6]. The adsorption advantage of MOFs which as one of new adsorbents may be diminished, because there are prone to hydration reactions and instable in the water molecules [7–9]. Natural polymers such as chitosan, cellulose and lignin are made from hydrophilic monomers crosslinked by covalent or non-covalent bonding interactions (e.g. hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic bonding, electrostatic interactions and π-π stacking) [10–13], which demonstrate reversible phase changes in response to a variety of external stimuli [14–17] and have been utilized in the synthesis of hydrogels as adsorbents for the removal of heavy metals from wastewater [18–20]. However, the application of hydrogels is substantially restricted by the relatively homogeneous adsorption groups and the difficulty of exposing some adsorption sites [19].

Polymer hydrogels, which combine the tunable specific functional groups of polymers with the hydrophilic and biocompatible properties of hydrogels, have gained much attention as adsorbents in the treatment of heavy metals. Zhao et al. [21] prepared a new CS-CMC hydrogel with enhanced adsorption capacity for divalent heavy metal ions by cross-linking CS with a highly concentrated CMC solution through irradiation. Milster et al. [22] showed that the newly prepared P(HEMA-co-AM)/PVA IPN had a maximum adsorption capacity of 200.4 and 292.5 mg/g for Cu(Ⅱ) and Pb(Ⅱ), which is difficult to produce targeted adsorption of specific heavy metal ions. A polyacrylic acid-based hydrogel with the highest adsorption selectivity for Cr(Ⅱ) was cross-linked by Fo et al. [23], nevertheless, the adsorption capacity of 0.143 mg/g is unsatisfactory. Although the synthesised polymer hydrogel modifiers enhance the adsorption performance of the conventional hydrogels to some extent, there is still considerable potential for improvement in the adsorption capacity and selectivity of these modifications for specific heavy metals.

In order to obtain hydrogels with excellent physicochemical properties, three different functionalized polymer hydrogels of PEG, PAA and PAMPS were prepared by grafting the functional monomers on CS through using free radical polymerization using specific groups (—OH, —COOH and —SO3H) as functional monomers. A novel bifunctional modified polymer hydrogel PAM-PAMPS was prepared by crosslinking AM (containing —NH2 group) and AMPS. The adsorption capacities of four polymer hydrogels were investigated with several sets of adsorption isotherms and kinetics experiments, and their adsorption selectivity for Pb(Ⅱ) was tested. The experimental results show that PAM-PAMPS is superior to PEG, PAA and PAMPS in terms of the overall aspect, after which the adsorption mechanism of PAM-PAMPS and the adsorption selectivity mechanism regarding Pb(Ⅱ) were characterized by XPS and DFT. Finally, PAM-PAMPS was evaluated for its resistance to interference in saline and humic acid environments, regeneration performance and practical industrial wastewater applications.

The preparation process of PAM-PAMPS was shown in Fig. 1 and Fig. S1 (Supporting information). The detailed synthesis steps, the source of chemicals, and the relevant experimental details were described in Supporting information.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Synthetic routes and SEM images of PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS hydrogels. | |

The surface morphology of the polymer hydrogels was observed by a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Nova NanoSEM 450, Japan). The pore size and specific surface area of the prepared hydrogel structures were analyzed by a pore size and specific surface area analyzer (BET, Quadrasorb SI, U. S. A.). The functional group species within the polymer hydrogels were investigated by infrared spectroscopy (XPS, FTIR-1500, China). Elemental analysis of the hydrogels before and after adsorption was performed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Axis Ultra DLD, Japan).

The energy relationships between the various structures were calculated by the DMol3 module in Material Studio. A hydrogel monolithic structure was first constructed using the DMol3 model, and the Becke and Lee-Yang-Parr (BLYP) functions in the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA) were used to optimize the structure. Finally, the energy is calculated from the optimized monomer structure and the adsorbent. The adsorption energy (Ead) is defined by the following equation (Eq. 1):

|

(1) |

where EHydrogels-Pb is the energy of hydrogel optimized for Pb(Ⅱ) adsorption, EPb is the energy of optimized Pb(Ⅱ), and EHydrogels represents the energy of hydrogel optimized.

The interiors of PEG, PAA, and PAMPS hydrogels are all cross-linked porous networks with pores of different sizes. The PEG feature a disordered stacked structure with smaller pore sizes, while the PAA are composed of pompom-shaped particles cross-linked with each other and have looser internal pores. The PAM-PAMPS consist of lamellar structures crossed in a honeycomb mesh, with a column-like growth trend of layers in the channels and a markedly more number of pore channels compared to the PAMPS (Fig. 1).

In the FTIR spectrum obtained for PEG, PAA, PAMPS, PAM-PAMPS (Fig. 2a). For PEG [24,25], the peaks at 1109 and 2879 cm−1 were attributed to the stretching vibration absorption peaks of C—O and —CH2 which was on the sub-methyl repeating unit of PEG chain. After AA grafting to CS, the characteristic peak of C═C at 1626 cm−1 of AA disappeared [26], while the asymmetric (1540 cm−1) and symmetric (1452 cm−1) characteristic absorption peaks of —COO— were observed [27,28]. The peaks of 1207 and 1039 cm−1 were assigned to asymmetric S—O stretching vibration, when AMPS grafted to CS [29,30]. After the formation of hydrogels by AM and AMPS, the stretching vibrational peak of C═C at 1612 cm−1 disappeared [26], the absorption peak of C═O shifted from 1670 cm−1 to 1660 cm−1, the characteristic peaks of C—N at 1390 and 1222 cm−1 appeared [31], and the S—O vibrational absorption peak at 1039 cm−1 was observed [28]. The above illustrates the successful synthesis of PEG, PAA, PAMPS, and PAM-PAMPS hydrogels.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS: (a) FT-IR spectra. (b) N2 adsorption and desorption curves. (c) Swelling ratio change curves. | |

The specific surface areas of the PEG, PAA, PAMPS, and PAM-PAMPS hydrogels were 1.197, 2.485, 18.30, and 25.58 m2/g, respectively (Fig. 2b). The larger the specific surface area, the larger the contact area with Pb(Ⅱ) and the more favorable for adsorption. The swelling ratios of the four hydrogels increased rapidly within 10 min. As the swelling time increased, the original morphology of PEG was destroyed due to its own poor mechanical properties, and the flaky solids kept detaching from the main body to the extent that it was difficult to collect the effective gel mass, thus the swelling ratio experiment of PEG was stopped at 100 min. The swelling ratios of the other three hydrogels slowed down and gradually reached the swelling equilibrium (Fig. 2c). The ratio of water absorption and swelling of hydrogels was related to the number of active hydrophilic groups inside the hydrogel and the internal spatial network structure [32]. The PAM-PAMPS was able to reach the swelling equilibrium in less than 40 min, which indicated its faster swelling ratio and more internal hydrophilic groups.

The isotherm plots (Fig. 3a) of the adsorption of Pb(Ⅱ) by the four hydrogels at an optimum pH of 5 (Fig. S4a in Supporting information) showed that the maximum adsorption capacities of PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS were 104.44, 356.74, 428.45 and 541.90 mg/g, respectively, all of which first increased with increasing Pb(Ⅱ) concentration until equilibrium was reached. The polymer hydrogels were abundant in adsorption vacancies during the first 5 min of the initial phase (Fig. 3b): PEG(—OH), PAA(—COOH), PAMPS(—SO3H) and PAM-PAMPS(—NH2, —SO3H). Among them, the adsorption capacity of Pb(Ⅱ) by PAM-PAMPS rose almost linearly, this was mainly attributed to the fact that the —NH2 and —SO3H in the hydrogel structure were mostly located in the negative electrostatic formula region and the number of effective sites was high, which enhanced the interaction force and contact area for binding with Pb(Ⅱ) during the swelling process [33,34], and the concentration difference also drove the reaction to be accelerated. The adsorption tended to saturate until the adsorption equilibrium at high concentration, cause the active adsorption sites inside the hydrogel were almost completely occupied by Pb(Ⅱ). Meanwhile, the correlation coefficient of Langmuir model (R2 = 0.982) for PAM-PAMPS was higher than that of Freundlich model (R2 = 0.917), which indicated that the adsorption sites were homogeneous and cannot be combined with other adsorbates after being occupied by Pb(Ⅱ), and that the controlling step might be assigned to chemisorption between PAM-PAMPS and Pb(Ⅱ). The adsorption kinetic curve (Fig. 3c) showed that PAA had a higher adsorption rate in the initial stage, Pb(Ⅱ) entered the three-dimensional network structure of PAA through the pore channel and quickly aligned with the —COOH. PAM-PAMPS had a larger specific surface area and pore size compared to PAMPS. The porous network structure effectively retarded the diffusion rate of Pb(Ⅱ) in the hydrogel. The number of available adsorption sites were ligated and ion exchanged with Pb(Ⅱ), so that the adsorption capacity of PAM-PAMPS reached about 80% of the equilibrium in 3 min. For PAM-PAMPS, the pseudo-second-order kinetic model (R2 = 0.986) can describe the adsorption process better than the pseudo-first-order kinetic model (R2 = 0.905), indicating that the kinetic adsorption process of Pb(Ⅱ) by PAM-PAMPS is mainly controlled by the chemical interaction between the active adsorption site and Pb(Ⅱ) [35,36]. Meanwhile, PAMPAMPS hydrogels had a higher adsorption capacity for Pb(Ⅱ) compared to some adsorbents (Fig. 3d) [37–42].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS: (a) Langmuir and Freundlich isothermal adsorption curves of Pb(Ⅱ). (b) Electrostatic potential energy. The regions of the most negative electrostatic potential and the most positive electrostatic potential are displayed by blue and red colors. (c) Adsorption kinetics curves of Pb(Ⅱ). (d) Comparison of the adsorption capacity of some adsorbents for Pb(Ⅱ). | |

To further clarify the binding mechanism of PAM-PAMPS with Pb(Ⅱ), XPS analysis was performed on PAM-PAMPS before and after adsorption. XPS analysis of PEG (Figs. S2a and b in Supporting information), PAA (Figs. S2c and d in Supporting information), and PAMPS (Figs. S2e and f in Supporting information) were also performed as a reference. C 1s (284.99 eV), N 1s (399.73 eV), O 1s (529.26 eV) and S 2p (169.5 and 168.4 eV) were detected before PAM-PAMPS adsorption and the characteristic peak of Pb 4f (138.8 eV) also appeared in the full spectrum after adsorption, which indicated that Pb(Ⅱ) was adsorbed (Fig. 4a). In the S 2p spectrum (Fig. 4b), the three sets of peaks appearing at 167.45, 167.42 and 166.26 eV were due to the ion exchange of —SO3H and —SO3+ groups with Pb(Ⅱ) after the adsorption of Pb(Ⅱ) and the increase of the electron cloud around the group, resulting in a shift of the binding energy [43]. While the N 1s spectrum after adsorption, the characteristic peak was shifted from 399.26 eV to 398.64 eV on account of the coordination between —NH2 and Pb(Ⅱ) (Fig. 4c) [44]. This indicated that PAM-PAMPS binded to Pb(Ⅱ) during the adsorption process through the synergistic effects of ion exchange and coordination, of which came from the contribution of the —SO3H and —NH2, respectively.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. XPS spectrum before and after adsorption of Pb(Ⅱ): (a) Full range XPS spectrum. (b) S 2p. (c) N 1s. | |

The selectivity for adsorption of specific metal ions is also one of the factors that measure the performance of adsorbents. In the selective separation experiments performed in binary mixture solutions, compared with other metal ions, PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS hydrogels showed significantly stronger adsorption capacity for Pb(Ⅱ) (Fig. S3 in Supporting information). The adsorption capacity of PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS for Pb(Ⅱ) were 64.4, 118.6, 171.43 and 185.04 mg/g which were still higher than for Ni(Ⅱ), Cu(Ⅱ), Cd(Ⅱ), Co(Ⅱ) (Fig. 5a). The dispersibility coefficient and selectivity coefficient of different polymer hydrogels are usually chosen to evaluate the adsorption selectivity. As shown in Table S1 (Supporting information), the dispersibility coefficient of PAM-PAMPS, PEG, PAA and PAMPS for Pb(Ⅱ) were significantly better compared to Ni(Ⅱ), Cu(Ⅱ), Cd(Ⅱ) and Co(Ⅱ), resulting in the high selectivity coefficient. Specifically, the selectivity coefficient of PAM-PAMPS for Ni(Ⅱ), Cu(Ⅱ) Cd(Ⅱ) and Co(Ⅱ) were 29.327, 20.199, 4.195 and 16.576, respectively (Table S1), indicating that PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS had excellent selectivity for Pb(Ⅱ) and anti-interference ability.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. PEG, PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS: (a) Multiple selective adsorption. (b) Binding point models and binding energies with Pb(Ⅱ) at different binding sites. | |

The PAA, PAMPS and PAM-PAMPS adsorption energy values were −1.7671, −2.2863 and −2.3470 eV, respectively (Fig. 5b), obtained by DFT for structural optimization and energy calculations. Lower adsorption energy values demonstrated that more adsorption sites are provided and the reaction is more likely to occur [45]. While PAM-PAMPS possesses the largest negative value, suggesting that Pb(Ⅱ) prefers to bind to PAM-PAMPS to form stable complexes for the selective capture of Pb(Ⅱ) largest negative value, suggesting that Pb(Ⅱ) prefers to bind to PAM-PAMPS to form stable complexes for the selective capture of Pb(Ⅱ).

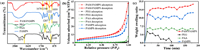

The adsorption performance and selectivity were integrated, PAM-PAMPS was tested for practical application in various environmental conditions. PAM-PAMPS maintained about 90% removal of Pb(Ⅱ) in NaNO3 solutions at concentrations of 0–1.0 mol/L, manifesting that salinity had little effect on adsorption (Fig. 6a). Natural water has a high humic acid content, the large molecular structure of humic acid will occupy the pore channels of the adsorbent and reduce the efficiency of inter-ion mass transfer [46]. The effect of different concentrations of humic acid on the removal rate of Pb(Ⅱ) was tested, (Fig. 6b) showed that humic acid had little effect on the removal ratio of Pb(Ⅱ), probably due to the large size of humic acid particles and the dense porous structure inside the hydrogel, which was not conducive to the retention of humic acid molecules. PAM-PAMPS achieved a removal ratio of nearly 92% in the first cycle and maintaind a removal ratio of about 89% after four regenerations of the material by adsorption-desorption. PAM-PAMPS hydrogels can remove almost most of Pb(Ⅱ), and the treated Pb(Ⅱ)-containing wastewater meets the industrial discharge standard (1 mg/L) (GB 25466-2010) (Figs. 6c and d). Compared with the other three hydrogels (Figs. S4b and c in Supporting information), the PAM-PAMPS hydrogel has excellent resistance to external interference and potential to treat industrial wastewater. In addition, the temperature had almost no effect on the adsorption performance of PAM-PAMPS (Fig. S5 in Supporting information) indicating that PAM-PAMPS has good recyclability and structural stability.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. PAM-PAMPS hydrogels: (a) Effect of salt concentration on Pb(Ⅱ) removal efficiency. (b) Effect of humic acid on Pb(Ⅱ) removal efficiency. (c) Recycling. (d) Practical application. | |

In summary, we report a new bifunctional modified polymer hydrogel PAM-PAMPS. The maximum adsorption of Pb(Ⅱ) by PAM-PAMPS is 541.90 mg/g at pH 5, which can maintain high adsorption under acidic and alkaline conditions, and is highly selective for Pb(Ⅱ) in coexisting solutions of various heavy metal ions. FT-IR and XPS prove that the adsorption of Pb(Ⅱ) by PAM-PAMPS is synergetic through coordination with —NH2 and ion exchange of —SO3H. The lower adsorption energy obtained from DFT calculations suggests that the excellent selectivity for Pb(Ⅱ) is due to the formation of the most stable complexes between PAM-PAMPS and Pb(Ⅱ). Furthermore, PAM-PAMPS maintained an adsorption efficiency of about 90% after four regeneration cycles. The amazing adsorption performance of PAM-PAMPS modified by bifunctionalisation on Pb(Ⅱ) and its practical application provide a new approach for the preparation of new polymer hydrogels by bifunctionalisation. Although polymer hydrogel monomers have not been adequately studied, the amazing adsorption performance and practical applications achieved utilizing the synergistic effects of the bifunctional polymer hydrogel PAM-PAMPS provide a new approach for the preparation of new polymer hydrogels by bifunctionalization.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis study was financially supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 52125002), the National Science Foundation of China (No. 52100043), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2019YFC1907900), the National Science Foundation of Jiangxi Province (No. 20224BAB203048).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109158.

| [1] |

Y. Song, Z. Zhao, J. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3169-3174. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.03.001 |

| [2] |

J. Li, Z. Zhao, Y. Song, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3231-3236. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.03.086 |

| [3] |

Y. Zhao, R. Zhang, H. Liu, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 375 (2019) 122011. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.122011 |

| [4] |

F. Liu, S. You, Z. Wang, et al., ACS ES&T Eng. 1 (2021) 1342-1350. |

| [5] |

A. Altwala, R. Mokaya, Energy Environ. Sci. 13 (2020) 2967-2978. DOI:10.1039/D0EE01340D |

| [6] |

X.H. Wang, H.R. Cheng, G.Z. Ye, et al., Chemosphere 287 (2022) 131995. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131995 |

| [7] |

Y.C. Jeong, J.W. Seo, J.H. Kim, et al., Nano Res. 12 (2019) 1921-1930. DOI:10.1007/s12274-019-2459-8 |

| [8] |

S. Li, Y. Gao, N. Li, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 14 (2021) 1897-1927. DOI:10.1039/D0EE03697H |

| [9] |

M. Li, Y. Liu, F. Li, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 55 (2021) 13209-13218. |

| [10] |

S. Huang, L. Hou, T. Li, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2110140. DOI:10.1002/adma.202110140 |

| [11] |

H. Guo, T. Nakajima, D. Hourdet, et al., Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) 1970177. DOI:10.1002/adma.201970177 |

| [12] |

H. Fan, J. Wang, Z. Tao, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 5127. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13171-9 |

| [13] |

F. Li, Y. Zhu, B. You, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 20 (2010) 669-676. DOI:10.1002/adfm.200901245 |

| [14] |

J. Wu, Y. Qu, K. Shi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 29 (2018) 1819-1823. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.10.004 |

| [15] |

M. Saadli, D.L. Braunmiller, A. Mourran, et al., Small 19 (2023) 2207035. DOI:10.1002/smll.202207035 |

| [16] |

Y. Zhao, C.Y. Lo, L. Ruan, et al., Sci. Robot. 6 (2021) eabd5483. DOI:10.1126/scirobotics.abd5483 |

| [17] |

Y. Hu, J.Y. Ying, Mater. Today 63 (2023) 188-209. DOI:10.1016/j.mattod.2022.12.003 |

| [18] |

M. Alizadehgiashi, N. Khuu, A. Khabibullin, et al., ACS Nano 12 (2018) 8160-8168. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.8b03202 |

| [19] |

P. Samaddar, S. Kumar, K.H. Kim, Polym. Rev. 59 (2019) 418-464. DOI:10.1080/15583724.2018.1548477 |

| [20] |

K. Gul, R.Y. Gan, C.X. Sun, et al., Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 62 (2022) 3817-3832. DOI:10.1080/10408398.2020.1870034 |

| [21] |

L. Zhao, H. Mitomo, J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 110 (2008) 1388-1395. DOI:10.1002/app.28718 |

| [22] |

S. Milster, R. Chudoba, M. Kanduc, et al., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21 (2019) 6588-6599. DOI:10.1039/C8CP07601D |

| [23] |

F.O. Gokmen, E. Yaman, S. Temel, Microchem. J. 168 (2021) 106357. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2021.106357 |

| [24] |

C. Li, H. Yu, Y. Song, et al., Renew Energy 121 (2018) 45-52. DOI:10.1016/j.renene.2017.12.089 |

| [25] |

N. Gogoi, M. Barooah, G. Majumdar, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7 (2015) 3058-3067. DOI:10.1021/am506558d |

| [26] |

M.A. Gauthier, I. Stangel, T.H. Ellis, et al., Biomaterials 26 (2005) 6440-6448. DOI:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.039 |

| [27] |

Y. Zhu, W. Wang, H. Zhang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 327 (2017) 982-991. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2017.06.169 |

| [28] |

W. Kong, Q. Yue, Q. Li, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 668 (2019) 1165-1174. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.095 |

| [29] |

B. Yi, R. Rajagopalan, H.C. Foley, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (2006) 11307-11313. DOI:10.1021/ja063518x |

| [30] |

J. Gardy, A. Hassanpour, X. Lai, et al., Appl. Catal. B 207 (2017) 297-310. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2017.01.080 |

| [31] |

S. Chen, J. Deng, C. Ye, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 410 (2021) 128435. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.128435 |

| [32] |

H. Ji, X. Song, Z. Shi, et al., ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 6 (2018) 5950-5958. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b04323 |

| [33] |

Q. Zuo, H. Shi, C. Liu, et al., J. Membr. Sci. 669 (2023) 121323. DOI:10.1016/j.memsci.2022.121323 |

| [34] |

X. Ding, W. Yu, X. Sheng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107485. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.04.083 |

| [35] |

J. Liu, L. Zeng, S. Liao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2849-2853. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.08.017 |

| [36] |

X. Sheng, H. Shi, D. You, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 437 (2022) 135367. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2022.135367 |

| [37] |

D. Alexander, R. Ellerby, A. Hernandez, et al., Microchem. J. 135 (2017) 129-139. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2017.08.001 |

| [38] |

A.E. Amin, M.E. Goher, A.S. El-Shamy, et al., Egypt. J. Aquat. Biol. Fish. 24 (2020) 623-637. DOI:10.21608/ejabf.2020.75965 |

| [39] |

J. Lozano-Montante, R. Garza-Hernández, M. Sánchez, et al., Polymers 13 (2021) 3166. DOI:10.3390/polym13183166 |

| [40] |

B.L. Rivas, S.A. Pooley, C. Muñoz, et al., Polym. Bull. 64 (2010) 41-52. DOI:10.1007/s00289-009-0133-0 |

| [41] |

M. Xiao, J.J.C. Hu, Cellulose 24 (2017) 2545-2557. DOI:10.1007/s10570-017-1287-9 |

| [42] |

B. Zhao, H. Jiang, Z. Lin, et al., Carbohydr. Polym. 224 (2019) 115022. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115022 |

| [43] |

B. Jiang, Y. Qi, X. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3556-3560. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.03.053 |

| [44] |

C.B. Godiya, X. Cheng, D. Li, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 364 (2019) 28-38. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.09.076 |

| [45] |

J. Kim, S. Kang, J. Lim, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 11 (2018) 2677-2683. |

| [46] |

H. Ji, Y. Zhu, J. Duan, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 2163-2168. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.06.004 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35