b Key Laboratory of Colloid and Interface Chemistry, Ministry of Education, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Shandong University, Ji'nan 250100, China;

c School of Mechanical Engineering, Chengdu University, Chengdu 610106, China

In the current field of energy storage, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) based on layered transition metal oxides or lithium iron phosphate as the cathode and graphite as the anode, have experienced a prosperous development and expansion over the past few decades [1,2]. However, due to limitations in theoretical capacity, it is challenging to achieve a significant increase in the energy density for LIBs. Additionally, the employment of expensive and toxic nickel-based and cobalt-based cathode materials restricts the widespread application. Therefore, there is an expectation to attain new energy storage systems with higher energy storage capacity at reasonable costs [3,4]. Among various emerging energy storage systems, considerable attention has been focused on sulfur cathode materials, which offers a high theoretical specific capacity (1675 mAh/g), high energy density (2600 Wh/kg, Fig. 1a) and low cost for lithium-sulfur batteries (LSBs) [2,5,6]. Therefore, LSBs are considered as one of the most promising battery systems for the next generation of energy storage systems.

|

Download:

|

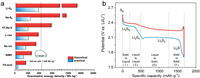

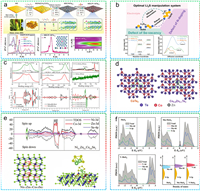

| Fig. 1. (a) Comparison of the theoretical and practical energy density between different battery systems. (b) An ideal charge-discharge curve with different sulfur-containing species at different stages. | |

The oxidation–reduction reactions of LSBs, complex intermediate products are formed accompanied by the transfer of multiple electrons. At the beginning of discharge process, the S8 on the cathode is reduced to form long-chain lithium polysulfides (Li2Sx, 6 < x ≤ 8, LiPSs). Subsequently, lithium ions continue to participate in the reaction, causing the transformation of long-chain LiPSs into short-chain LiPSs, ultimately resulting in the formation of solid Li2S at the end of the discharge [7,8]. The charging process involves the reverse reaction for establishing a reversible cycle, where the corresponding voltage-capacity curve for the charge-discharge process of LSBs are illustrated in Fig. 1b. Originated from the 16-electron transfer of S8 molecules in the redox process, a remarkably high theoretical capacity of 1675 mAh/g can be provided for the LSBs. Before complete conversion into insoluble Li2S2/Li2S products, a series of soluble LiPSs is formed from the S8 ring molecules and shuttle between the cathode and anode, contributing to the "shuttle effect", which reduces the Coulombic efficiency and active material utilization of LSBs [9,10]. Additionally, S and Li2S exhibit high electronic and ionic insulating properties, thereby reducing the kinetics of the cathode reaction. Finally, the disparate densities of S (α phase, 2.07 g/cm3) and Li2S (1.66 g/cm3) lead to severe cracking or even pulverization of the cathode [11].

In recent years, efforts have been made by researchers to address the issues mentioned above by improving key components of LSBs, including the cathode, separator, electrolyte, binder, and anode. Considering that the reaction process of LSBs involves a multi-step electrochemical process with rate-limiting steps (Li2S4 → Li2S2 and Li2S2 → Li2S), the introduction of electrocatalysts is the most effective approach to enhance the kinetics of electrode reactions, thereby fundamentally addressing the shuttle effect in LSBs. Generally, catalytic materials can efficiently adsorb LiPSs by introducing bonding mechanisms, and markedly enhancing the utilization efficiency of active materials. Simultaneously, the reduction of the activation barrier by catalysts expedites the conversion rate of active substances, leading to outstanding battery performance, particularly under high rates. Additionally, the strategic establishment of a conductive network serves to optimize the electron transfer process, resulting in significantly reduced resistance and the provision of heightened conductivity to the battery. These three mechanisms synergistically operate, collectively optimizing the performance of LSBs and laying a robust foundation for achieving high rate and large discharge capacity [12,13].

Reported catalytic materials are primarily composed of metal-based compounds, including metal oxides, phosphides, carbides, and nitrides [14–21]. In practical applications, these catalytic materials are mainly employed as cathode additives, sulfur hosts, and intermediate layers between the cathode and separator [22–24]. Among these, chalcogenide catalytic materials (CCMs) have been widely developed due to their unique crystal structure, electronic properties, and chemical composition [25,26]. In particular, CCMs exhibit higher conductivity compared to metal oxides, and the M-X (X = S, Se, Te) bonds in CCMs are weaker than the M-O bonds in metal oxides, which are beneficial to facilitate electrochemical conversion kinetics [27–31]. Moreover, compared to metal carbides, metal sulfides characterized with lower Li+ diffusion barriers, contribute to the rapid LiPS conversion and enhanced sulfur utilization [32,33]. Metal selenides and metal tellurides with narrower band gaps facilitate reduced energy jumps for electrons, consequently foster enhanced metal conductivity, which in turn, accelerate the redox kinetics of sulfur and contribute to an intricate and efficient electrochemical transformation [34,35]. The systematic overview and summary of the application of CCMs in LSBs are currently lacking, encompassing advanced CCMs synthesis technology, the in-depth exploration of catalytic mechanisms, and the outstanding performance exhibited by CCMs.

In consideration of catalytic activity predominantly originated from the material surface and the tri-phase (catalystic materials/carbon host/electrolyte) interfaces, a notable reduction in overall structural efficiency is encountered, thereby constraining catalytic activity [36–38]. Simultaneously, the high loading of electrocatalysts leads to limitations in mass/charge transport [39,40]. Addressing the aforementioned issues, current research, on the one hand, focuses on structural modulation engineering, including morphological engineering, interfacial engineering, and crystal engineering. These strategies aim to enhance the electrocatalytic activity of CCMs by increasing the number of active sites and optimizing interfacial properties [41–47]. On the other hand, achieving rapid electron transfer and catalytic sulfur conversion processes are pursued by judiciously manipulating the electronic structure, which aims to enhance the intrinsic activity of the catalyst. Derived from this, a series of electronic modulation strategies has emerged, including vacancy engineering, doping engineering, and so forth. However, there is a lack of systematic summarization for these modulation strategies, particularly concerning CCMs.

In this review, the representative achievements of CCMs in recent years are systematically summarized [48,49]. On this basis, regulation strategies for optimizing the catalytic performance of CCMs are elaborated, mainly involving strategys targeting the structure and electronic states of CCMs to enhance the intrinsic electrocatalytic activity. Special attention is devoted to the structure-function relationship between the structure/electronic states of CCMs and the electrocatalytic sulfur conversion activity. Finally, the challenges and future prospects inherent in CCMs for the advancement of high-performance LSBs are anticipated, aiming to provide further insights into advanced catalysis research and guide the construction of catalysts with high activity, selectivity, and excellent cycling stability.

2. Application of CCMs in Li-S batteriesIn the realm of LSBs, a myriad of catalysts, such as nitrides, carbides, phosphides, and single-atom materials, has emerged and provided a diverse array of options to enhance battery performance [50–53]. Among these catalysts, CCMs stand out due to their distinctive electronic structure and active sites, imparting remarkable advantages to the forefront of LSBs technology [54,55]. The advantages of CCMs manifest in various aspects [28,56,57]. Firstly, their unique electronic structure furnishes abundant reaction sites, contributing to heightened catalytic activity and electrode reaction rates. Secondly, the high conductivity of sulfur-containing compounds facilitates electron transfer, reducing internal battery resistance and thereby enhancing overall battery efficiency. The enhanced conductivity of catalysts facilitates effective electron coupling with sulfur-containing species, expeditiously hastening the kinetics of the lithium-sulfur reaction. Additionally, their chemical stability further contributes to increased cycling life and stability of LSBs.

2.1. SulfidesAmong CCMs, the electronic structure of sulfides endows them with abundant reaction sites, thereby enhancing their catalytic activity in LSBs [58,59]. This characteristic is crucial for facilitating the progression of lithium-sulfur reactions, contributing to improved reaction kinetics and overall battery performance [60,61]. Furthermore, sulfides typically exhibit favorable conductivity, which is beneficial for facilitating rapid electron transfer and reducing internal battery resistance, thereby enhancing energy conversion efficiency. This is crucial for the power performance and charge-discharge efficiency of the LSBs. In terms of synthesis, sulfides can often be prepared through relatively simple synthetic methods, reducing the cost of catalyst preparation [2]. This constitutes a significant advantage for achieving large-scale production and commercial application. Additionally, the robust chemical stability of sulfides enables them to withstand chemical changes during cycling progress in LSBs, which contributing to prolonged service life. This comprehensive set of attributes positions sulfides as a promising catalyst in LSBs, addressing key factors related to catalytic activity, conductivity, cost-effectiveness, and chemical stability.

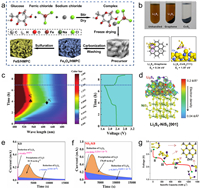

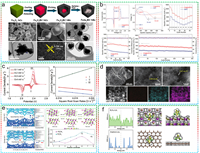

As catalyst materials in LSBs, the sulfides based on Fe, Co, Ni, Cu and Zn, initially captivated researchers due to factors such as abundant raw materials, facile synthesis, and tunable performance [62–68]. Chen et al. systematically investigated first-row transition metal compounds (ScS, TiS, VS, CrS, MnS, FeS, CoS, NiS, CuS, and ZnS) as sulfur host materials in LSBs to elucidate general principles of sulfur host design [69]. Periodic trends were deduced through theoretical calculations based on density functional theory (DFT). The strong S bonds primarily arise from charge transfer between transition metal atoms and S atoms in LiPSs, distinct from Li bonds predominantly induced by dipole-dipole interactions. Further evidence demonstrated the crucial role of transition metals in constructing S bonds with robust anchoring effects. This discovery provided universally applicable principles for the rational design of sulfide-based sulfur cathode materials and the screening of undeveloped materials. Considering the ease of electron acquisition or loss in the d-orbital electron layer of transition metal cations within metal sulfides, favoring their application in electrochemical catalysis, iron sulfide holds the potential to emerge as an economically efficient alternative to precious metal-based Pt catalysts. Ren et al. employed a one-step sulfurization strategy to synthesize a ferrous sulfide decorated honeycomb-like porous carbon (FeS/HMPC) for serving as separator modifier (FeS/HMPC-PP) for LSBs (Fig. 2a) [70]. DFT results confirmed that, compared to iron oxide, the positive shift in the d-band center of Fe facilitates strong adsorption for various LiPSs primarily through (Fe-S) bonds. Moreover, FeS exhibited a minimal diffusion barrier for typical LiPSs migration. Consequently, FeS/HMPC-PP not only effectively mitigate the shuttle effect but also catalyze the redox reactions of LiPSs.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) The synthesis process of Fe3O4/HMPC and FeS/HMPC. Reproduced with permission [70]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (b) Visualized adsorption and binding geometries between CoS2 and LiPSs. Reproduced with permission [71]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (c) In situ UV–vis spectroscopy of LSBs with DHCP/S cathodes and relevant galvanostatic charge-discharge curves. Reproduced with permission [73]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (d) Binding geometry and electron density of Li2S4 on NiS2. Reproduced with permission [74]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. Potentiostatic discharge curves of (e) KB and (f) NiS2/KB-based LiPS batteries with Li2S8 solution. Reproduced with permission [75]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (g) Illustration for the discharge process of LSBs. Reproduced with permission [77]. Copyright 2018, Elsevier. | |

In previous studies, researchers observed that the anisotropic characteristics of conductive surfaces facilitated the transfer of charges from the host material to LiPSs. However, the mechanism by which polar surfaces accelerated the redox reactions of LiPSs has not been clearly elucidated. Considering that, Yuan et al. incorporated sulfophilic cobalt disulfide (CoS2) into the carbon/sulfur cathode, which exhibited a robust interaction between LiPSs and CoS2 under operational conditions [71]. Electrochemical evidence affirmed the CoS2-electrolyte interface as a potent adsorption and activation site for polar LiPSs, thereby expedited the redox reactions of LiPSs (Fig. 2b). The heightened reactivity of LiPSs ensures not only effective polarization mitigation, but also maintain high discharge capacity and stable cycling performance over 2000 cycles (capacity decay is 0.034% per cycle at 0.2 C). Although the chemical bonding between metal compounds and LiPSs provides an effective solution to mitigate the shuttle effect in LSBs, the Sabatier principle predicts that excessive adsorption often hinders the conversion of LiPSs [72]. Therefore, establishing a synergistic mechanism between "strong adsorption" and "rapid conversion" of LiPSs is a crucial strategy. Zeng et al. devised defect-rich Co9S8 hollow prism columns (DHCPs) as host and catalytic materials for LSBs, concurrently achieved "strong adsorption" and "rapid conversion" of LiPSs [73]. In addition, DHCPs effectively promoted the generation of S3.− radicals during the discharge process (Fig. 2c). In the case of relatively high conversion barriers in the "liquid-liquid" reaction, the generated S3.− radicals toke charge of the rapid conversion reaction through a unique reaction pathway.

Typically, metal sulfides exist primarily in the form of large particles with varying degrees of aggregation, significantly reducing the surface area available for LiPSs adsorption and limiting the quantity of loadable sulfur species. In Li-S electrochemistry, the introduction of porous carbon media with abundant dispersed spaces to prepare functional hybrid S substrates is an effective method to obtain advanced nanostructured metal sulfides. Considering the ease of synthesis and versatility of controllable nanostructure (such as hollow sphere, nanowire, and layer-rolled morphologies), Luo et al. employed a bio-molecule-assisted self-assembly synthesis method to construct a NiS2-reduced graphene oxide (NiS2-RGO) three-dimensional sponge-like structure, which provided abundant active sites for the adsorption and localization of LiPSs [74]. Experimental data and first-principles calculations confirmed the enhanced LiPSs adsorption capability of NiS2 (Fig. 2d). Furthermore, the chemical coupling between NiS2 and RGO formed during the in-situ synthesis provided a 3D electron pathway, which facilitated charge transfer to the NiS2-LiPSs interface and therefore triggered rapid redox kinetics of LiPSs conversion and excellent rate performance (C/20–4C). Consequently, the self-assembled hybrid structure simultaneously improved static LiPSs trapping capability and dynamic reversibility of LiPSs conversion. Therefore, it is evident that selecting an appropriate carbon carrier is advantageous for fully exploiting the catalytic activity of sulfides. Considering the practicality of the catalytic material, Liang et al. designed a cubic pyrite-structured NiS2 nanosphere-modified Ketjen black@sulfur (NiS2/KB@S) composite material as a cathode material for LSBs [75]. The NiS2 nanospheres exhibited a favorable impact on the adsorption and catalytic performance of LiPSs, further enhanced the redox kinetics (Figs. 2e and f). Simultaneously, Ketjen black, as a widely employed conductive material, demonstrated substantial application potential.

Benefiting from high electrical conductivity (870 S/cm), copper sulfide (CuS) is considered a highly attractive catalytic material for LSBs. Moreover, during the lithiation process, CuS exhibits distinct voltage plateaus at 2.0 and 1.7 V, aligning with the discharge of most sulfur electrodes. Therefore, the contributed capacity can compensate for its occupied weight and volume within the electrode, which challenging to achieve for other materials. Sun et al. first reported that the use of CuS as a multifunctional sulfur cathode additive can enhance the discharge capacity of LSBs and improve the utilization of sulfur [76]. Inspired by the work on various sulfides, Xu et al. first reported the catalytic effect of ZnS nanospheres on the redox kinetics of LiPSs in LSBs (Fig. 2g) [77]. Ex-situ SEM and visualized experiments confirmed a significant reduction in the reaction between migrating LiPSs and the lithium anode, with insulating Li2S2/Li2S uniformly deposited on the ZnS-carbon black/S cathode.

Two-dimensional transition metal sulfides (TMSs) are a class of layered materials with a fundamental chemical formula represented as MS2, where M denotes transition metal elements, including but not limited to Ti, V, Ta, Mo, W, Re, etc. TMSs typically exhibit a three-layer structure (S-M-S), with transition metal atoms M situated between two layers of sulfur (S) atoms. In this arrangement, atoms within each layer are covalently bonded, and van der Waals forces bind adjacent layers, providing pathways for the rapid transfer of Li+ ions and electrons [78]. The selection of layered transition metal sulfides with superior electrical conductivity and the design of the microstructure of their composite cathode materials have become hotspots in current research.

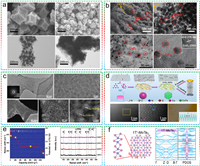

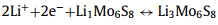

He et al. synthesized a well-designed, self-supported, 3D graphene/1T-MoS2 (3DG/TM) heterostructure as an efficient electrocatalyst for LiPSs conversion (Fig. 3a) [79]. Raman spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and high-resolution TEM collectively confirmed the presence of the 1T-MoS2. The metallic 1T-MoS2 nanosheets exhibited abundant active sites, well hydrophilicity and high electronic conductivity (6 orders of magnitude higher than 2H-MoS2). Benefited from these, the LSBs assembled with 1T-MoS2 demonstrated superior specific capacity (reversible discharge capacity of 1181 mAh/g vs. ~1000 mAh/g) and cycling performance (capacity retention of 72.6% vs. 42.6%) compared to the 2H MoS2. Lei et al. employed a simple hydrothermal method to directly grow 2D WS2 nanosheets on carbon cloth [80]. The ultrathin WS2 nanosheets (a few nanometers in thick and sub-micrometer in length) possessed a high active surface area and low contact resistance, provided a high specific surface area for sulfur loading and facilitated rapid electron transfer (Fig. 3b). Wu et al. pioneered a biconductive VS2−MXene heterostructure electrocatalyst serving as a highly efficient sulfur host [81]. The VS2−MXene amalgamated the advantages of ultrafast anchoring catalysis (VS2) and excellent nucleation/surface diffusion (MXene), to expedite the bidirectional redox kinetics of sulfur (Figs. 3c and d). Benefited from the amalgamation of these advantages, the nucleation and decomposition of Li2S were finely regulated, while the shuttle of LiPSs was effectively suppressed. Through the intricately designed compact sulfur cathode, the high-density S/VS2−MXene cathode (density: 1.91 g/cm3, conductivity: 76.3 S/m) delivered an impressive capacity of 1571 Ah/L.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) High-resolution TEM images of 3DG/TM and the corresponding elemental mapping images. Reproduced with permission [79]. Copyright 2019, Royal Society of Chemistry. (b) Schematic illustration for the preparation of WS2 vertically aligned on the CNFs and the corresponding morphological characterization. Reproduced with permission [80]. Copyright 2017, Wiley-VCH. (c) Synthesis schematic of 1T-VS2−MXene heterosturctured catalyst and the synergistic mechanism for the catalytic conversion of sulfur species. (d) The adsorption energies of LiPSs and TDOS plots for 1T-VS2−MXene and 1T-VS2. Reproduced with permission [81]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. | |

In addition to conventional sulfur cathodes, the application of Li2S cathodes aims to balance high energy density with the suppression of volume expansion. However, challenges persist, including insulating properties of Li2S and shuttle effect of LiPSs. Seh et al. first reported the effective use of two-dimensional layered transition metal disulfides (TiS2, ZrS2 and VS2) as encapsulation materials for lithium sulfur cathodes [82]. These materials combined high conductivity and strong binding affinity for Li2S/Li2Sn. In particular, lithium-sulfur cathodes with TiS2 as the encapsulation material demonstrated high-rate performance (503 mAh/gLi2S at 4 C) and a high areal capacity (3.0 mAh/cm2 with mass-loading of 5.3 mgLi2S/cm2).

2.2. Selenides/telluridesIn comparison to sulfides, selenides and tellurides have emerged as novel catalyst materials in recent years for LSBs, owing to their unique electronic structure and tunable crystal structure. Firstly, from the perspective of electronic structure, selenides and tellurides possess moderate band gaps and abundant charge carriers, facilitating the easier transmission of electrons within the material, thereby endowing them with higher electrical conductivity (S: 5 × 10–28 S/m, Se: 1 × 10–3 S/m, Te: 102 S/m) [83]. Secondly, the crystal structure of selenides and tellurides is tunable and can be precisely controlled through synthesis methods and structural engineering [84]. This tunable structure not only contributes to the distribution of catalytically active sites but also enhances the electron transfer efficiency.

Iron-based chalcogenides have garnered widespread attention in the fields of electrocatalysis and energy storage due to their excellent conductivity, strong catalytic activity, and relatively low cost. Sun et al. synthesized carbon nanobox-encapsulated FeSe2 nanoparticles (FeSe2@C NBs) through the selenization reaction of yolk-shell Fe3O4@C (Fig. 4a) [85]. These FeSe2@C NBs were served as a multifunctional sulfur host for suppressing the shuttle effect and accelerating the redox conversion of LiPSs, which exhibited better sulfur utilization, higher rate performance, and longer cycling life compared to Fe3O4@C. To address constrained long-term cycling life caused by the nanostructure imperfections, small surface area, and pore structure, Ye et al. developed an efficient CoSe electrocatalyst with a hierarchical, porous polyhedron (CS@HPP) nanostructure through a simple one-step carbonization-selenization method [86]. The defined nanostructure and synergistic engineering of different components not only provide abundant catalytic active sites for the chemical adsorption of LiPSs but also accelerate the diffusion of Li ions, the conversion of LiPSs, and the precipitation/decomposition of Li2S. The sulfur cathode of CS@HPP exhibited a discharge specific capacity of 1634.9 mAh/g at 0.1 C, equivalent to a sulfur utilization rate of 97.6% (Fig. 4b).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) The schematic fabrication process and morphological characterization of FeSe2@C NB. Reproduced with permission [85]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (b) Typical CV curves, discharge/charge curves, rate capabilities and cycling performances LSBs based on CS@HPP and AB sulfur cathodes. Reproduced with permission [86]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (c) CV curves of S@u-NCSe electrode at various scan rates and plot of CV peak current for peaks Ⅰ, Ⅱ, and Ⅲ versus the square root of the scan rates. Reproduced with permission [87]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. (d) HAADF-HRTEM images and STEM-EDX elemental mappings of MoSe2@rGO hybrid. Reproduced with permission [88]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. (e) HSE06 band structure and density of states of Bi2Se3 and I-Bi2Se3, and optimized adsorption configuration for the Li2S decomposition on Bi2Se3 and I-Bi2Se3. Reproduced with permission [89]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (f) DOS and band-decomposed charge density distribution for the Bi2Te3-Li2S4 and graphene- Li2S4 adsorption systems. Reproduced with permission [90]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. | |

In addition, an urchin-like structure of NiCo2Se4 (NCSe) was prepared by Zhang et al. through a two-step hydrothermal method, which was specifically chosen as the sulfur host given the metallic properties and synergistic effect between Ni and Co atoms [87]. The Li+ diffusion coefficient demonstrated that the tubular structure with high conductivity possessed the advantage of rapid electron transfer, thereby facilitated the electrochemical reaction kinetics (Fig. 4c). Additionally, adsorption experimental confirmed that the polar bimetallic structure enhanced the confinement of LiPSs and alleviated the volume expansion effect. Considering the numerous exciting studies on selenides, Tian et al. employed a one-pot hydrothermal treatment to hybridize sulfur-affinitive few-layer MoSe2 nanosheets with reduced graphene oxide (MoSe2@rGO) relied on their similar 2D structure, which provided more surface anchoring sites (Fig. 4d) [88]. The results indicated that sulfur could be uniformly distributed on MoSe2@rGO, while the sulfur tended to aggregate on pristine rGO, suggested better sulfur affinity for MoSe2.

Apart from the transition metal-based selenides mentioned above, candidates based on main group metals within the potential selenides family have been overlooked so far. Selenium bismuth (Bi2Se3) is typically an n-type degenerate semiconductor with a low bandgap of 0.3 eV and a layered crystal structure, which consists of double atomic layers Se-B-Se-Bi-Se bonded together through weak van der Waals interactions. This high conductivity and layered structure endow it with suitability for serving as a sulfur host in LSBs. Additionally, the variable oxidation states of bismuth and selenium imply highly potential catalytic activity. Li et al. proposed an innovative sulfur host based on iodine-doped bismuth selenide (I-Bi2Se3) to regulate the shuttle effect and conversion process of LiPSs [89]. DFT calculations and experimental results indicated that I-Bi2Se3 possessed suitable electronic structure and micro/nanostructure, which is favorable to accelerate Li+ diffusion and electron transfer, facilitate the chemical adsorption and electrocatalytic conversion of LiPSs, and reduce the barrier for the precipitation/decomposition of Li2S (Fig. 4e).

To enhance electron transport between S and the conductive substrate, topological insulators (TIs) are considered promising candidate materials, which feature a Dirac cone band structure and excellent charge transport properties. Additionally, owing to strong spin-orbit coupling, TIs manifest topologically protected conducting surface states and provide robust tolerance to defects and impurities. Song et al. introduced the Bi2Te3 TI as a catalyst in LSBs, which revealed that Bi2Te3 effectively anchored LiPSs through Bi-S and Te-Li interactions [90]. Additionally, Bi2Te3 demonstrated intrinsic catalytic activity for both the sulfur reduction reaction and LiPSs oxidation reaction. Importantly, band-decomposed charge density distribution of the Bi2Te3-Li2S4 adsorption system indicated the establishment of efficient charge transfer pathways between Bi2Te3 and adsorbed sulfur species for facilitating rapid electron exchange (Fig. 4f).

In addition to the aforementioned prolific research progress concerning CCMs in LSBs, the inherent disparities in properties delineate the trajectories of their future development. Primarily, sulfides, being one of the most prevalent catalytic materials in LSBs, have garnered considerable attention owing to their abundance in resources and comparatively modest production costs. Nevertheless, sulfides exhibit relatively diminished electrocatalytic activity, necessitating further strides in engineering design and material modulation to ameliorate their performance. In contrast, when juxtaposed with sulfides, selenides and tellurides manifest augmented electrocatalytic prowess within LSBs, which stems from the richer electronic state densities and an abundance of catalytic sites, thereby fortifying the kinetics of sulfur reduction and oxidation reactions. However, the scarcity, toxicity, and intricacies entailed in their preparation may impede the feasibility of their large-scale application. In terms of cost considerations, sulfides typically enjoy conspicuous cost advantages, given the ubiquity and relative affordability of sulfur resource. Conversely, the elevated costs associated with selenium and tellurium materials procurement and processing may profoundly impact the aggregate costs of batteries when scaling up industrial production.

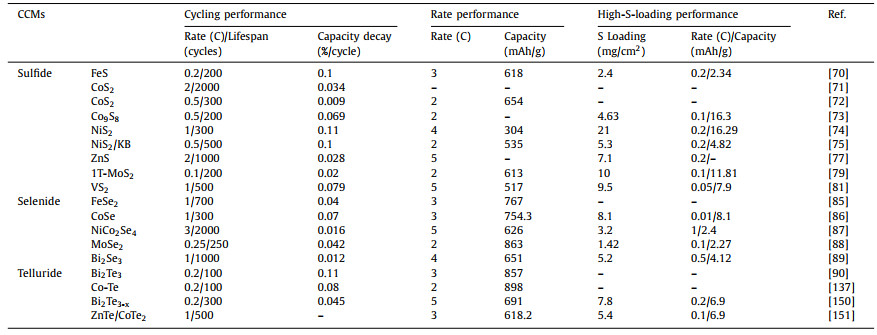

Table 1 condenses the electrochemical performance of some typical recently proposed CCMs which were utilized in LSBs. In the specific application of LSBs, CCMs not only serve as catalysts to enhance reaction efficiency but also, through the modulation of their structure and internal electronic configuration, further optimize catalytic activity. These unique advantages endow them with highly promising research direction in the field of LSBs. The superiority in structural optimization and electronic structure modulation paves the way for the advancement of LSBs technology, which are summarized below.

|

|

Table 1 Summary of electrochemical performance parameters for CCMs in LSBs. |

In LSBs, the intricate optimization through structural engineering emerges as a crucial strategy for enhancing the performance of catalytic materials [91–93]. Through in-depth research and clever design of the structural aspects of CCMs, the quantity and distribution of active sites can be precisely controlled, and thereby significantly influencing the efficiency of electrocatalytic reactions. In this section, the critical role of structural engineering in CCMs for LSBs is thoroughly explored, focusing primarily on morphology engineering, surface/interface engineering, and crystal engineering.

3.1. Morphology engineeringThe phenomenon of size effects, wherein material properties undergo significant changes at the nanoscale, has attracted considerable attention as a research direction for enhancing the performance of catalytic materials in LSBs [67,94–96]. Through the modulation of the size for catalytic materials, higher specific surface areas and more active sites can be achieved, leading to an effective enhancement of the interaction between catalytic materials and sulfurous species. This, in turn, facilitates the intricate electrochemical reactions within LSBs.

Size regulation: The precise engineering of morphology not only improves the electrochemical activity of catalysts but also holds the potential to optimize the cycling stability and rate performance of LSBs. Therefore, by fully leveraging size effects, the design and optimization of catalytic materials can be achieved with greater precision, offering new possibilities for the development of LSBs. At the macroscopic scale, a particulate morphology is typically assumed by CCMs, owing to the more favorable kinetic and thermodynamic conditions for particle formation during the synthesis process [97,98]. Reducing the size of the material is conductive to increase its surface area-to-volume ratio, thereby exposing more active sites for constructing three-phase (conductive substrate/catalytic material/electrolyte) interface. Effectively utilizing the confinement effect of carbon materials is considered an efficient means to achieve precise control over the morphology of materials. This involves employing carbon nanotubes, graphene, and similar materials as templates or catalysts during the synthesis process.

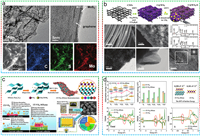

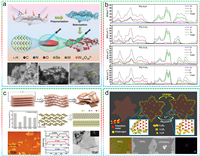

Carbon derived from MOFs possesses abundant pore structures and polar groups, playing a unique role in dispersing catalytic materials and limiting their growth. Zhou et al. synthesized a S/CoS2-N-doped carbon polyhedra (S/CoS2-NC) through the thermal treatment of sulfur and cobalt-containing nitrogen-doped carbon polyhedra derived from the carbonization of metal-organic framework polyhedra ZIF-67 (Fig. 5a) [99]. The N-doped carbon polyhedra not only provide electronic conductivity but also serve as embedding sites for cobalt sulfide nanoparticles with enhanced dispersion. Li et al. designed a layer-by-layer electrode structure, where each layer of the electrode consists of ultrafine CoS2-nanoparticle-embedded porous carbon evenly grown on both sides of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) [100]. The average size of the CoS2 nanoparticles obtained from metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) is approximately ≈ 10 nm (Fig. 5b). The layered porous structure of this interconnected conductive framework facilitates rapid ion and electron transfer while providing ample space to confine LiPSs, thereby improving the kinetics of LiPSs oxidation and reduction. Tian et al. reported sulfophilic VSe2 ultrafine nanocrystals anchored on nitrogen-doped graphene to modify separators of LSBs for the first time [101]. As shown in TEM images (Fig. 5c), the VSe2 nanocrystals with a diameter of ~2.5 nm were uniformly fixed on graphene nanosheets, which provided numerous active sites for the chemical adsorption of LiPSs and thereby facilitated the nucleation and growth of Li2S. The higher exchange current density and lithium ion diffusion coefficient confirmed the accelerated kinetics of the reaction, which endowed the LSBs with exceptional rate capability up to 8 C (600 mAh/g) and higher areal capacity of 4.04 mAh/cm2 with sulfur areal loading up to 6.1 mg/cm2.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) SEM and TEM images of Co-NC and S/CoS2-NC composites. Reproduced with permission [99]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier. (b) SEM and TEM images of CoS2-LBLCN. Reproduced with permission [100]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. (c) TEM and HTREM images of VSe2 NC@NG. The inset shows the corresponding SAED pattern. Reproduced with permission [101]. Copyright 2020, Springer. (d) Schematic illustrating the synthesis process and AC-HADDF-STEM images of CoTe. Reproduced with permission [102]. Copyright 2022, Springer. (e) In situ time-resolved Raman images and selected Raman spectroscopy of the cathode with ReS2@CNT/S. Reproduced with permission [106]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH. (f) Layer structure of 1T′-MoTe2 and the concentrated DOS near the Fermi level. Reproduced with permission [105]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

The effective dispersion and composite of catalysts can be achieved through the synergistic action of multi-dimensional (0D, 1D, 2D and 3D) carbon, representing an effective strategy to enhance catalytic activity. Inspired by the body structure of an octopus the synergistic action of multidimensional carbon has also been proven to be a viable approach for achieving the dispersion of sulfides. With this approach, Wang et al. designed a multifunctional composite material comprised 0D NiS2 (sucker), 1D CNTs (tentacle), and a 3D carbon (3DC) (body) to achieve a combination of high specific surface area, excellent conductivity, and adsorption capabilities [62]. Li and colleagues developed highly conductive CoTe nanocrystals anchored on a one-dimensional (1D) carbon nanotube and two-dimensional (2D) graphene composite (CoTe NCGs, Fig. 5d) [102]. The one-dimensional nanotubes interconnected with graphene to form a conductive framework that prevented excessive graphene stacking and enhanced the loading of CoTe nanocrystals. Additionally, the CoTe nanocrystals are enveloped by a thin layer of graphene, which was promoting stability and preventing aggregation. This designed structure was not only beneficial for regulating the conversion of LiPSs on the cathode but also facilitate the uniform deposition of lithium ions on the anode side. Benefitted from this merits, the assembled LSBs still exhibited satisfactory performance even under high sulfur loading (6.0 mg/cm2), extremely lean electrolyte (E/S of 4.2), and low N/P ratio (1.6:1). Ye et al. also took advantage of the synergistic benefits of multidimensional materials, for designing a combination of 0D CoZn-Se nanoparticles and 2D N-MX nanosheets as co-catalysts [103]. This combination possessed double binding sites that are favorable for lithium and sulfur, effectively immobilized and catalyzed the conversion of LiPSs intermediates.

Quantum dots (QDs) materials, characterized by their ultra-small size, excellent dispersibility, and unique quantum connections, have been demonstrated to significantly enhance interactions between hosts and guests, lowering reaction barriers. This endows them with excellent catalytic effects on LiPSs. Zhao et al. utilized carbon nanotubes (CNTs) loaded ZnSe QDs as framework and encapsulated with layer-structured Ni(OH)2, constructed a novel core-shell ZnSe-CNTs/S@Ni(OH)2 [104]. The carbon nanotube network modified with ZnSe QDs not only serve as a conductive framework but also physically and chemically restrict the diffusion of LiPSs. The constructed LSBs exhibited enhanced electrochemical performance with a rate capacity of 665.0 mAh/g at 2 C.

Morphology regulation of 2D CCMs: Typical 2D CCMs often manifest in two structures: the triangular prismatic 1T/1T' phase and the hexagonal 2H phase. These structural differences influence the electronic properties and catalytic activity of the materials, where the 1T/1T' phase contributes to enhanced conductivity and thereby exhibits superior performance in catalytic reactions [105]. He et al. employed a hydrothermal reaction to achieve the in-situ growth of metal two-dimensional 1T'-ReS2 nanosheets on one-dimensional carbon nanotubes (ReS2@CNT), which was employed to effectively suppress "sulfur shuttle" and promote the redox reactions of LiPSs [106]. As shown in the in-suit Raman spectrum in Fig. 5e, the combination of structural and size regulation can synergistically optimize the catalytic activity for rapid conversation of LiPSs. And the pouch cell manufactured with a ReS2@CNT/S cathode delivers a low capacity decay rate of 0.22% per cycle. In light of this, Yu et al. first extensively investigated the characteristics MoTe2 with different phases (2H, 1T, and 1T′) guided by DFT calculations, and confirmed that 1T'-MoTe2 exhibited the highest concentration density of states (DOS) near the Fermi level [105]. From the crystal structure perspective, 1T'-MoTe2 belonged to the P21/m space group, and the different arrangement of top and bottom Te atoms resulted in vertical intrinsic dipole differences, further leaded to the enhancement of the intrinsic conductivity (Fig. 5f). Guided by this, 1T′-MoTe2 quantum dots decorated 3D graphene (MTQ@3DG) was designed and employed as a catalyst for S cathode. The effective suppression of shuttle effect in the MTQ@3DG/S cathode was intuitively confirmed through in-situ Raman spectroscopy studies. Benefitting from this, the assembled pouch cell exhibited high gravimetric energy density based on active sulfur of 1395.8 Wh/kgs, which is delightful news for the practical application of flexible LSBs.

In addition to the regulation of the phase, considering that catalytic sites are mostly located at the edge positions of 2D CCMs, the number of active sites can be increased by reducing the number and size of layers. Wang et al. prepared the WSe2 ultrathin flakelets uniformly dispersed on the surface of nitrogen-doped graphene (WSe2/NG) by a self-sacrificing template of melamine formaldehyde resin [107]. The WSe2 flakelets characterized with uniform dispersion, few-layered structure (2–7 layers), and small dimensions (20 nm in length), which provided more edge sites for simultaneously regulating the behavior of sulfur and lithium (Fig. 6a). The WSe2/NG was simultaneously served as hosts for anode and cathode, and assembled Li-S full cells exhibited remarkable rate performance and stable cycling stability even at a higher sulfur loading of 10.5 mg/cm2 with a negative to positive electrode capacity (N/P) ratio of 1.4:1. More importantly, the pouch-type Li-S full cell exhibits excellent cycling stability, with a low capacity decay rate of 0.3% per cycle over 65 cycles, and mitigated polarization in charge-discharge curves. Wu et al. utilized the porous structure of Al-based MOF (Al(OH)-(1, 4-H2NDC)·2H2O) to achieve the uniform loading and anchoring of ultrathin MoS2 nanosheets onto mesoporous carbon pyrolyzed from MOF [108]. As shown in TEM images, ultra-thin MoS2 (with a thickness of 5 nm, equivalent to 6–8 layers) was laterally grow along the surface of the carbon layer, which provided a high specific surface area (455.9 m2/g) for S loading.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a) Synthesis approach, SEM, TEM and HRTEM images of WSe2/NG. Reproduced with permission [107]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. (b) Total and projected density of states of LiPSs anchored on TiS2 monolayer. Reproduced with permission [110]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (c) Schematic of the electrochemical lithium (EC-Li) intercalation/exfoliation, AFM image and XRD patterns of SSNS/CNT composites. Reproduced with permission [111]. Copyright 2018, Wiley-VCH. (d) Schematic illustration of chemical vapor deposition-grown transition metal dichalcogenide nanosheets, optical and SEM images of MoS2 flakes as-grown by the CVD process. Reproduced with permission [112]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. | |

In the quest to unleash catalytic activity, the peeling of 2D CCMs into single layers stands out as an ideal approach. The monolayer structure, with its abundance of active surface sites, allows for the full exploitation of electronic properties, thereby amplifying catalytic performance. Chen et al. investigated the potential application of monolayer FeS as an anchoring material in LSBs through systematic DFT calculations [109]. These results revealed that LiPSs were effectively immobilized on the FeS monolayer through van der Waals physical adsorption with moderate strength, characterized by adsorption energies ranging from 1.00 eV to 3.26 eV Conversely, the anchoring of Li2S on the FeS monolayer primarily occurred through chemical interactions. Furthermore, the ultra-small diffusion barrier of Li2S on the FeS monolayer facilitated rapid transfer, which was benefitted to inhibit Li2S agglomeration and enhance reaction rates. This research suggested that a monolayer of FeS may serve as an excellent anchoring material for high-performance LSBs. Zhao et al. also assessed the properties of a TiS2 monolayer through DFT calculations [110]. Simulation results indicated that the TiS2 monolayer exhibited dynamic and thermal stability, with effective LiPSs adsorption energies ranged from -1.38 eV to -3.54 eV (Fig. 6b). Despite the validated theoretical advantages of monolayer CCMs, the controllable synthesis method still remains developing. Yao et al. prepared monolayer Sb2S3 nanosheets through an electrochemical Li intercalation and exfoliation strategy, which integrated as a novel 2D coupling material into the separator of LSBs for the first time [111]. DFT calculations confirmed that the exfoliated 2D Sb2S3 nanosheets consisted of (010) planes. Moreover, as observed in TEM and AFM, evident single-layer Sb2S3 nanosheets composed of two half-layers with a uniform thickness of 1.132 nm (Fig. 6c). Benefiting from the unique advantages of the monolayer material, LSBs prepared with its modified separator exhibited a significant improvement in capacity retention and cycling stability. The chemical vapor deposition was employed by Babu et al. to prepared WS2/MoS2 monolayer and few-layer flakes [112]. Furthermore, large-scale production of WS2 nanosheets was achieved using a shear exfoliation method to meet the commercial demands of the battery industry (Fig. 6d). Most importantly, compared to carbon electrodes (2.52 mA/cm2), the exfoliated WS2 exhibited higher electrocatalytic activity (8.53 mA/cm2), which endowed them with attractiveness for the redox reactions of LiPSs.

The design of traditional 2D CCMs into ultra-small nanocrystals are also regarded as an effective method, which can not only achieve high edge exposure but also induce the surface to generate a large number of unsaturated sulfur sites conducive for coordination. For example, the ultrasmall WS2 nanoclusters with the size around 2 nm and 1T MoS2 nanodots were designed to trap and propel the redox reactions of LiPSs, which delivered remarkable Li-S electrochemical performance and proposed a promising catalyst design strategy [63,113].

3.2. Surface/interface engineeringConsidering that the transformation of insulated sulfur in LSBs primarily occurs at the three-phase interface of the conductive substrate, electrolyte, and catalyst, which provides the necessary electrons and ions for the conversion process and firmly adsorbs reactants [114]. Optimizing the properties of this crucial three-phase interface for catalytic materials is a rational approach to enhance the performance of LSBs. The synergistic effects at this interface not only offer excellent adsorption capabilities but also selectively regulate the conversion kinetics of LiPSs.

In-depth understanding and meticulous design of the structure and properties of this interface are expected to significantly improve the overall performance of LSBs. Wong et al. employed chemical vapor deposition to grow few-layered MoSe2 on nitrogen-doped reduced graphene oxide and subsequently prepared the cathode of LSBs through sulfur infiltration [115]. The surface functionality of MoSe2 was illustrated through DFT calculations and electrochemical performance assessments, where selenium edge sites on the MoSe2 surface exhibited strong adsorption affinity for LiPSs. Simultaneously, the reduction of the lithium-ion diffusion barrier on the MoSe2 surface facilitated the rapid diffusion of lithium ions.

In light of the intrinsic low electrical conductivity of the compound, surface carbon material compositing is an effective approach to enhance its catalytic performance. Wu et al. employed MOF (ZIF-67) as template and precursor to synthesize a polyhedral hollow structure of CoSe2 through a simple one-step carbonization-selenization method [116]. The surface of CoSe2 was coated with a layer of conductive polypyrrole (PPy) to address the poor conductivity of CoSe2. The prepared CoSe2@PPy-S composite cathode exhibited a superior reversible capacity of 341 mAh/g at 3 C and excellent cycling stability with a capacity decay rate of 0.072% per cycle. Yang et al. stabilized the surface of ZnSe nanoparticles using nitrogen-doped hollow carbon polyhedrons and constructed a novel hollow nano-reactor structure [117]. This carefully designed structure can regulate volume expansion, preventing damage to the cathode due to the hollow structure. Transition state calculations confirmed that the (002) crystal plane of ZnSe delivered a lower Li+ migration barrier than the (110) crystal plane, indicated that the presence of ZnSe accelerated the diffusion of Li+ (Fig. 7a).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. (a) Illustration of stages of Li2S4 diffusing and schematic illustration of the LiPS catalytic conversion on ZnSe. Reproduced with permission [117]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (b) Schematic diagram of the synthetic process of VTe2@MgO by CVD, TEM image of VTe2@MgO, HRTEM image, SAED pattern of VTe2@MgO and cycling performance of S/VTe2@MgO cathode at 1.0 C. Reproduced with permission [119]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (c) Schematic diagram illustration the synthesis procedure of the CoSe2/Co3O4@NC-CNT heterostructure and band structure for Co3O4@NC-CNT, CoSe2@NC-CNT and CoSe2/Co3O4@NC-CNT. Reproduced with permission [121]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (d) Li2S oxidization LSV curves, Tafel plots and CV curves of the FeSe–MnSe/NBC-based cell. SEM images of FeSe-MnSe/NBC and FeSe/C after discharge. Reproduced with permission [125]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (e) Schematic illustration of the growth process and SEM images of Gr-MxSey@GF. Reproduced with permission [128]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (f) Schematic of the surface-gelation and gelation-inhibition processes in LSBs with conventional or TEA solution. Optical images of the gelation-inhibition phenomenon in the TEA solution. TEM image of the MoS2 surface after being treated in the TEA solution. Side view of the differential charge density analysis of a TEA molecule adsorbed on the MoS2 (110) surface. Reproduced with permission [129]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. | |

The construction of heterostructure can achieve advantageous complementarity between components, establishing stable interfaces for the adsorption-migration-conversion of sulfur-containing species. Simultaneously, the formation of heterogeneous interfaces with built-in electric field holds tremendous potential to drive the transport of electrons and ions, thereby enhancing reaction kinetics [118]. Given that the excellent adsorption properties of oxides for LiPSs and their compatibility with chalcogenide in the same main group, the construction of heterostructures with oxides is a prioritized and extensively studied approach, such as VTe2@MgO [119], WS2-WO3 [120], CoSe2/Co3O4 [121], SnO2/SnSe2 [122] and VO-VSe [123].

In order to achieve facile and controlled growth of vanadium telluride (VTe2), Wang et al. developed a scalable chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method to prepare VTe2@MgO heterostructures served as the sulfur host material for LSBs (Fig. 7b) [119]. The metallic VTe2@MgO synthesized by in-situ vapor-phase method ensured a clean and intact interface, which facilitated the dual-function synergy of VTe2 and MgO. The S/VTe2@MgO cathode with a sulfur loading of 1.6 mg/cm2 exhibited stable cycling at 1 C, with a decay rate of only 0.055% per cycle after 1000 cycles. Zhang et al. reported the fabrication of WS2-WO3 heterostructures through an in-situ sulfidation method [120]. The interface structure was modulated by controlling the degree of sulfidation, which balanced the trapping capability of WO3 and the catalytic activity of WS2 towards LiPSs. A close and atomically matched heterostructure interface contact was formed between WS2 and WO3 for generating abundant active sites. The assembled LSBs exhibited excellent rate performance and cycling stability with only 5 wt% of WS2–WO3 heterostructure added to the cathode. The inherent mechanism of the improvement in conductivity by constructing heterojunction interfaces was discovered by Chu et al. [121]. Near the Fermi level, the projected density of states (PDOS) of the CoSe2/Co3O4 heterostructure was higher than that of CoSe2 and Co3O4, thereby promoted electron transfer in the CoSe2/Co3O4 interface (Fig. 7c). This indicated that the conductivity of the CoSe2/Co3O4 heterostructure was superior than those of CoSe2 and Co3O4, thereby improved the performance of LSBs. The fabricated pouch cells with a sulfur loading of 4.2 mg/cm2 exhibited excellent capacity retention of 83.6% and 71.6% after 100 cycles at 0.1 and 0.2 C, respectively. Through combined DFT calculations and catalytic tests, Li et al. further confirmed that the heterostructure structure was conducive to reduce the Gibbs free energy change and decomposition barrier for the nucleation and decomposition of Li2S, respectively. The constructed N-doped carbon loaded vanadium selenides and vanadium oxides structure (NC@VO-VSe) exhibited strong adsorption and accelerated bidirectional conversion functionality for LiPSs [123].

The preparation of two different CCMs into a heterostructure can fully leverage the advantages of two components, which was also widely explored, such as Co9S8@MoS2 [124], FeSe–MnSe [125], ZnSe-CoSe2 [126] and ZnTe/CoTe2. Zhang et al. designed a N, B co-doped hollow carbon loaded dense FeSe-MnSe heterostructure (FeSe-MnSe/NBC) through a simple hydrothermal reaction [125]. The three-dimensional deposition and growth of Li2S were cleverly guided by rich heterostructure interface, which effectively prevented catalyst passivation and facilitated the continuous Li+ diffusion and subsequent Li2S nucleation (Fig. 7d). Catalytic performance tests and DFT calculations confirmed that the hetero-interface formed by FeSe and MnSe contributed rapid electron transfer, adjusted electronic structure, and reduced energy barrier for SRR, which significantly enhanced the kinetics of sulfur conversion.

Constructing heterostructures by combining CCMs with other types of catalyst materials provides a more structured design strategy to further optimize the interfacial state of CCMs. Wang et al. constructed a MoS2−MoN heterostructure nanosheet on a carbon nanotube array as a self-supported cathode [127]. The Li+ migration pathway and Li2S nucleation curve revealed the role of formed heterojunction interface. That is, MoN served as a promoting donor to provide coupled electrons for accelerated redox reactions of LiPSs, while MoS2 with 2D layered structure offered a smooth diffusion pathway for Li+. Through the respective advantages of MoN and MoS2, the "adsorption-diffusion-conversion" process of LiPSs was mutually promoted. In addition, Wang et al. employed a continuous low-temperature chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method to grow a series of graphene-metal selenide (Gr-MxSey) heterostructures on glass fiber (Fig. 7e) [128]. Such tailored architectures not only provide abundant active sites but also achieve the synergistic effect between the polar framework and heterogeneous interface, which effectively mitigated the shuttle effect and guiding the electrochemical functions of Li2S nucleation/decomposition. More importantly, the flexible Li–S pouch cell based on this Gr-MoSe2 modified separator deliverd good device performance (with a capacity decay of 0.25% per cycle over 100 cycles).

Considering the surface evolves of catalyst with voltage and reaction, investigating the surface structural changes of catalytic material is of great significance for understanding the catalytic material mechanism. Li et al. first identified the surface gelation of disulfides (e.g., MoS2, FeS2, CoS2, NiS2, and WS2), where the Lewis acid sites triggered the ring-opening polymerization of dioxane and generated a surface gel layer on disulfides accompanied by reduced catalytic material activity [129]. To address this, the Lewis base triethylamine (TEA) was introduced into the electrolyte as a competitive inhibitor for eliminating the gel layer around the MoS2 particles, which can be observed in TEM images (Fig. 7f). The LSBs consisted of MoS2 catalytic material and TEA inhibitor exhibited a remarkable cycling life (250 stable cycles at 3 C) and improved rate capability. This work provided new insights into the actual surface structure of catalytic material for LSBs.

3.3. Crystal engineeringThrough crystal engineering optimization, precise control over the microstructure of catalysts can be achieved for maximizing catalytic activity. At the crystal phase level, the microcomposition of catalysts can be regulated by rationally designing and selecting the crystal structure, thereby influencing the distribution and density of surface-active sites and contributing to enhanced catalytic activity for specific reactions. For crystal plane, surface adsorption performance and reaction kinetics can be affected by controlling the growth direction and interplanar spacing of catalyst crystals. This molecular-level control not only optimizes the electronic structure and surface chemical properties of catalysts but also precisely influences the interaction between catalysts and active species. In the field of LSBs, the catalysts regulated by crystal engineering can better adapt to the complex electrochemical environment, enhance the conversion of LiPSs, optimize reaction kinetics, and effectively promote the performance of LSBs.

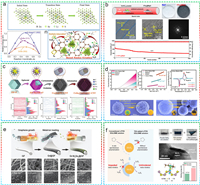

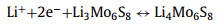

Lithiated crystal phases: Due to the overlapping lithium intercalating/deintercalating potential with the working voltage range of LSBs for certain types of CCMs (MoxSy, ZnSe, SnS, etc.), the in-situ lithium intercalating/deintercalating processes are inevitably induced when the corresponding catalytic materials operating in the charge-discharge processes of LSBs. These processes lead to unexpected changes from the original crystal structure. The newborn generated lithiated crystal phases are expected to exhibit surprising performance in the conversion of sulfur-containing species. Mo6S8 with both rapid lithium intercalation characteristics and strong redox properties was employed as a S cathode backbone by Xue et al. for the first time [130]. CV curves and corresponding in-situ XRD characterization confirmed that Mo6S8 exhibited electrochemical activity in the range of 1.7–2.8 V (Fig. 8a), with the following Li insertion process:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. (a) Cyclic voltammetry plot and in-situ XRD measurements of a Li|HMSC cell. Reproduced with permission [130]. Copyright 2019, Nature Publishing Group. (b) Gravimetric/volumetric energy densities comparison of LixMoS2-based Ah-level pouch cells with reported LSBs and its cycling stability at a current density of 2 mA/cm2. Reproduced with permission [132]. Copyright 2023, Nature Publishing Group. (c) Operando Raman spectra and ex-situ XRD patterns of Li–S chemistry reaction with respect to a SeVs-MoSe2@PP based cell at 0.2 C. Reproduced with permission [133]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH. (d) Sulfur K-edge XANES of the S/LE-MoS2 electrode with sulfur loading of 1.4 mg/cm2 at discharge and charge status. Reproduced with permission [134]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (e) HSE06 band structure and DOSs of NG, WSe2, and NG/WSe2 superlattice. Reproduced with permission [135]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. (f) AIMD simulations of the adsorption of S8 on CoTe2 and Co. Reproduced with permission [137]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. | |

The differential adsorption effects of Mo6S8 at various lithiumization degrees on sulfur-containing species were verified through calculations and adsorption experiments, where the Li1Mo6S8 and Li3Mo6S8 delivered higher absorbance for Li2S4. The Chevrel phase Mo6S8 with high electrochemical activity and volumetric density, was combined with S8 and incorporated into a button cell assembly with 10 wt% conductive carbons (carbon nanotubes and graphene) and 5 wt% binder. The assembled LSBs are characterized with a significant reduction in the cathode porosity and a low electrolyte/active material ratio of 1.2 µL/mg, which delivered excellent rate performance and cycling stability. More importantly, the pouch cell assembled with the hybrid Mo6S8-S8 composite achieved simultaneous energy density and volumetric energy density values of 366 Wh/kg and 581 Wh/L, respectively. Lu et al. further investigated the unique efficacy of Mo6S8 as a redox mediator [131]. Mo6S8 nanoparticles exhibited faster lithium-ion insertion kinetics compared to sulfur, and the generated LixMo6S8 particles displayed spontaneous redox reactivity with relevant LiPSs (such as Li4Mo6S8 + Li2S4 ↔ Li3Mo6S8 + Li2S, ΔG = –84 kJ/mol), which was regarded as the actural redox-catalyzed sulfur transformation mechanism with a quasi-solid pathway. The postmortem of cycled LSBs discovered that this pathway not only promote the uniform growth of Li2S by inhibiting its aggregation but also alleviate the corrosion of lithium metal anode caused by LiPSs. This similar prelithiation process and the enhancement of catalytic activity by lithiation intermediates have been observed and confirmed in ZnSe-CoSe2 and SnO2/SnSe2 heterostructures [122,126]. This novel structural regulation strategy is also considered an advanced approach to activate the catalytic performance of CCMs. It should be mentioned that, through an ex-situ technology, the prelithiation process of CCMs can be artificially manipulated to selectively prepare rational and high-performance catalytic materials. Li et al. chemically exfoliated MoS2 by butyllithium chemistry to prepare 1T-phase LixMoS2, which was confirmed by XRD, Raman spectroscopy and XPS [132]. The compact electrode assembled from single-layer nanosheets of metallic 1T-phase LixMoS2 exhibited high conductivity, wettability, and catalytic activity. The weight-level energy density of the pouch cell based on LixMoS2 at the ampere-hour level (1.3 ± 0.05 Ah) reached 441 Wh/kg, with a volume-level energy density of 735 Wh/L (Fig. 8b). The criteria for selecting lithium-storage CCMs and the design of electrode structures constitute a critically important and profoundly researched endeavor. Key considerations encompass:

(1) Precision in potential regulation: For lithium-storage catalyst materials, the potential for lithium extraction must be precisely within the charging and discharging voltage range of LSBs (1.7–2.8 V). This requirement aims to ensure that the lithium extraction reaction synchronizes seamlessly with sulfur conversion, thereby achieving the efficient operation of the battery.

(2) Structural stability: Throughout the lithium extraction process, it is imperative to maintain the structural integrity of catalytic materials, striving for the ideal state of a "zero-strain" material. This design objective aims to prevent adverse effects on catalytic activity and overall battery performance stemming from structural collapse.

(3) Control of lithiation intermediates: A clear understanding of how lithiumation intermediates regulate the performance of original CCMs is essential. Simultaneously, a profound comprehension of the interaction dynamics among sulfur-containing species is necessary. This involves in-depth analysis of how lithiation intermediates impact the performance of catalytic materials and an understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these interactions, facilitating the optimization of the overall performance of lithium-sulfur batteries.

Such comprehensive studies will contribute to advancing the CCMs and battery design, further enhancing the performance and reliability of LSBs.

In-suit interacting with LiPSs: In addition to Li insertion, the interaction between CCMs and polysulfide ion under specific conditions can also lead to a crystal transition to introduce a novel modulation effect on sulfur conversion progress. Wang et al. developed a universal salt-templating method for synthesizing defective MoX2 (XVs-MoX2, X = Se and S) in the presence of anionic vacancies [133]. The dynamic evolution of MoSe2 pre-catalysts was tracked through Raman spectroscopy and ex-situ XRD (Fig. 8c). The results confirmed that the MoSeS generated from the reaction between MoSe and polysulfide anions was the actual active catalyst. Comprehensive experimental and theoretical studies confirmed the catalytic ability of MoSeS to promote the conversion from Li2S2 to Li2S, thereby enhanced the capacity of LSBs.

Adjusting interlayer spacing: The research of 2D CCMs and their composites to improve the electrochemical performance of LSBs is growing. However, due to poor conductivity and limited interlayer spacing between adjacent CCMs monolayers severe aggregation effects are induced and therefor leading to the weakeness of catalytic activity. The inherent tunable properties of the superlattice structure of 2D CCMs are harnessed by continuously and precisely adjusting the interlayer spacing, which facilitates the creation of 2D channel with ion-selective capabilities and leads to a further expanded tunable range of catalytic performance. Pan et al. prepared layer-expanded MoS2 nanotubes (LE-MoS2) composed of layered superstructure nanosheets (-MoS2-carbon layer-MoS2-) through solvothermal synthesis and annealing treatment [134]. High-resolution TEM and XRD peak shifts confirmed the significant expansion of the (002) crystal plane of LE-MoS2 to 1.04 nm. Rapid and reversible signals of LiPSs were observed in the in-situ X-ray absorption near-edge structure spectra during charging/discharging progress, which confirmed the further enhanced phase transition dynamics as well as the immobilization of soluble LiPSs of LE-MoS2 (Fig. 8d). Zhang et al. prepared a WSe2 superlattice with high electrical conductivity by intercalating nitrogen-doped graphene (NG/WSe2), which accompanied by continuous modulation of the WSe2 interlayer spacing from 2.1 nm to 1.04 nm (Fig. 8e) [135]. DOS analysis indicated that the modulation of interlayer spacing effectively compressed the bandgap width, thereby achieved higher electrical conductivity. Charge density differential plot and adsorption experiments confirmed that NG/WSe2 could effectively facilitate Li+ transfer at the heterogeneous interface and achieve dual-effect adsorption towards LiPSs, thereby accelerated the kinetics of Li-S reactions and suppressed shuttle effects.

Other crystal engineering: In addition to the aforementioned strategies, crystal structure improvements induced by alloying, amorphization, high entropy engineering and heterogeneous atomic modulation have also been widely applied [136]. To address the sulfur poisoning phenomenon caused by the irreversible dissociation of adsorbed S8 molecules into S atoms on many transition metals (TMs) such as Fe, Co, and Ni, Song et al. employed an alloying strategy to regulate the crystal structure of Co (Fig. 8f). The tellurization process was employed to synthesize Co-Te alloy on hollow nitrogen-doped carbon spheres (Co-Te/NC), where Co atoms were exclusively coordinated with Te atoms without adjacency to other Co atoms [137]. Isolated Co sites exhibited moderate binding energy for S8 only at the top of S adsorption sites. The resistance to poisoning of the Co-Te alloy was confirmed through ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations, where the S8 molecules on the Co-Te surface could maintain an intact cyclic structure during the adsorption process. A non-crystalline transition metal polysulfide electrode with exceptional charge-discharge performance was reported by Sakuda et al., which characterized by a hybrid intercalation/deintercalation mechanism along with a conversion mechanism and contributed to significantly increased capacity. High-entropy materials, characterized by numerous uniformly dispersed crystal structures, exhibit a "cocktail effect" that promotes diverse adsorption sites both chemically and electronically. Theibault et al. synthesized high-entropy sulfide nanoparticles (Zn0.30Co0.31Cu0.19In0.13Ga0.06S) by partially exchanging cations on the basis of the Cu1.8S crystal structure [138]. Rotating disk electrode analysis indicated that the introduction of high-entropy nanoparticle catalysts enhanced the kinetics of the redox reactions of LiPSs.

4. Electronic engineeringModulating the intrinsic electronic structure of catalytic materials is regarded as a fundamental strategy for enhancing lithium-sulfur catalytic performance [24,139–143]. The adjustment of the electronic structure influences the charge state of active sites on the catalyst surface and the stability of reaction intermediates. By tuning intrinsic electronic structure parameters such as the band structure and electron distribution within orbitals, the electronic state of surface-active sites can be optimized and thereby enhancing the interaction strength with sulfurous species [26,144–146]. This optimization of catalyst contributes to improved efficiency in adsorption-migration-conversion behavior towards LiPSs and ultimately enhances catalytic performance.

4.1. Vacancies engineeringModulating the electronic structure through defect engineering allows for the optimization of lithium-sulfur catalytic performance, which comprises two primary approaches: the introduction of vacancies and heteroatom doping. The introduction of a vacancy entails the absence of a neighboring atom around the vacancy, leading to a change in local electron density. This adjustment of local electron density directly impacts the electronic state near the vacancy, encompassing the band structure and electron affinity and thereby affecting catalytic activity and adsorption performance. It should be mentioned that despite the exclusive interaction between surface vacancies and LiPSs, vacancy engineering stands in distinct contrast to the aforementioned surface/interface engineering. Vacancy engineering transcends mere regulation of surface defect sites, extending its influence to the holistic atomic composition and electronic structure of the material. Even internal vacancies within the material impart discernible effects on the overall catalytic performance, encompassing aspects such as ion transport and electrical conductivity. In contrast, surface/interface engineering predominantly concentrates on the adjustment of external characteristics, such as the physical morphology and surface properties of the material, refraining from direct involvement in alterations to the internal atomic structure of the material. Consequently, though these two engineering approaches exhibit distinctions in certain facets, their interconnection remains evident. Generally, vacancies are categorized into cationic vacancies (Fe, Cu) and anion vacancies (S, Se, Te).

Anion vacancies: Tian et al. employed a spray-drying process combined with subsequent chemical reduction and rapid thermal shock to prepare Sb2Se3-x/rGO composite microspheres, which were rich in selenium vacancies and served as separator modifiers in LSBs [147]. The presence of selenium vacancies was confirmed by electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy (EPR) and XPS (Fig. 9a). Compared to Sb2Se3, the DOS results revealed a significant state rearrangement and the emergence of shallow donor levels (defect levels) of Sb2Se3-x. Electrons below the Fermi level can transition to the defect levels, which generated hole charge carriers and reduced the barrier for electron conduction band transitions, thereby led to an enhancement in electrical conductivity. The LSBs modified with Sb2Se3-x/rGO-modified separator exhibited outstanding rate performance (8 C), excellent cycling stability (a capacity decay rate of only 0.027% per cycle), and maintained an areal capacity of 7.46 mAh/cm2 even under high sulfur loading (8.1 mg/cm2). It is worth noting that vacancies are not universally effective in the catalytic conversion of LiPSs. Du et al. proposed that a high concentration of oxygen vacancies reduced the conductivity of HNO, thereby slowed down the conversion process of LiPSs [148]. To investigate how the concentration of Se vacancies affects catalytic performance, Li et al. artificially introduced varying amounts of Se vacancies into 2D WSe2, which can be observed by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM, Fig. 9c) [149]. Through a systematic comparison, the impact of defects with different W/Se ratios on enhancing the cathodic processes of LSBs was quantitatively studied. The research ultimately confirmed that, at a moderate defect level, WSe1.51 exhibited optimal performance in adsorbing and catalyzing LiPSs conversion.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthetic procedure, EPR spectra and high-resolution XPS spectrafor the Sb2Se3-x/rGO microspheres. Reproduced with permission [147]. Copyright 2019, Wiley-VCH. (b) WT contour plots and calculated DOS of the synthesized Bi2Te3@CNs and Bi2Te3-x@NBCNs. Reproduced with permission [150]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH. (c) SAED image, the IFFT pattern and long cycling performances of the selected area of WSe1.51/CNT. Reproduced with permission [149]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (d) DOS and electron gain/loss of different atoms calculated by Bader charge analysis for v-ZnTe/CoTe2, ZnTe/CoTe2, CoTe2, and ZnTe. Reproduced with permission [151]. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH. (e) HSE06 band structures of Cu2Se and Cu1.8Se and the corresponding energy barrier of Li-ion diffusion. Reproduced with permission [152]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. | |

With the emergence of tellurides, Te vacancies have recently been employed to optimize the electronic structure of catalytic materials. Hu et al. synthesized topological insulator Bi2Te3-x with abundant Te vacancies in N and B co-doped carbon nanorods (Bi2Te3-x@NBCNs), and employed it as the sulfur host for high-performance LSBs [150]. As can be seen from the wavelet transform of XANES (Fig. 9b), a slight shift in the radial distance moved towards the negative direction, which indicated a noticeable change in the local electronic environment of the composite material. The results of DOS shown that the original B2Te3 exhibited a regular electronic distribution in the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO). However, when Te vacancies were introduced on the surface of Bi2Te3, the charge density distribution of bonding and antibonding orbitals displayed significant disorder. This indicated that the introduction of Te vacancies significantly reconstructed the surface charge density distribution, thereby activated the electrocatalytic activity of Bi2Te3–x. In addition, the conduction band of Bi2Te3-x was negatively shifted towards the Fermi level, indicated that Te vacancies can effectively enhance the electronic conductivity of the topological surface states, thereby accelerated the charge transfer ability between LiPSs and the electrocatalyst. Huang et al. combined Te vacancies with ZnTe/CoTe2 heterostructures to adjust the performance of sulfur reduction-oxidation catalysts [151]. DFT calculations indicated that the d-band center in the heterostructure was slightly close to the Fermi level (Fig. 9d). According to the d-band theory, the movement of the d-band center towards the Fermi level increased the probability of electrons filling the antibonding orbitals between the metal and the adsorbed molecules, thereby enhanced the adsorption capacity of ZnTe/CoTe2 towsrds sulfur. The ZnTe/CoTe2@NC/S-based pouch cells delivered superior capacitance retention rates 75.4% after 100 cycles at a current rate 3 C and the prepared electrode demonstrated practical application value by being capable of powering a temperature and humidity monitoring clock.

Cationic vacancies: The rational construction of cationic vacancies can also be employed to adjust the electronic structure, thereby achieving performance optimization of CCMs. Yang et al. proposed the addition of copper selenide (Cu2Se) nanoparticles to the cathode for capturing and accelerating the kinetics of LiPSs [152]. The crystal phase and copper vacancy (Cu1.8Se) concentration were employed to control the electronic structure, conductivity and affinity of copper selenide. As shown in the HSE06 band structures, the Fermi level of Cu1.8Se was located within a band, consistent with the degenerate/metallic properties and associated with the high hole density provided by the high density of Cu vacancies (Fig. 9e). In contrast, the Fermi level of Cu2Se was situated in the band gap, exhibited the character of p-type semiconductor. Boyjoo et al. reported a general method for synthesizing highly dispersed nanoscale pyrrhotite Fe1–xS particles, and confirmed the role of Fe vacancies in enhancing the adsorption capacity for LiPSs [153].

4.2. Heteroatom dopingSimilar to the vacancy introduction strategy, heteroatom doping is regarded as another promising approach to enhance the catalytic activity of CCMs. The incorporation of heteroatoms disrupts the periodicity of the original lattice, leading to changes in the local electronic structure. This alteration effectively adjusts the electrical conductivity and surface properties of the base material, thereby improving the electrocatalytic activity. Thus, heteroatom doping holds vast potential for the rational design of sulfur transformation. This section reviewed recent advances in heteroatom doping for enhancing the catalytic performance of CCMs in LSBs, which encompassed metals doping, non-metals doping, bimetallic doping, and their hybrids.

Non-metallic elements can typically be doped using common and readily available chemicals for simplifying the preparation process, which contributes to reduce production cost of the catalyst and provides a more economical choice for large-scale production and industrial applications. Song et al. prepared a nitrogen-doped CoTe2 served as an effective dual-anchored electrocatalyst, which can simultaneously bond to lithium and sulfur atoms in LiPSs through Te-Li/N-Li bonds and coordinating covalent Co-S bonds [154]. The surface electrostatic potential distribution indicated that the doped nitrogen increased the surface electronegativity of Co for enabling stronger sulfur adsorption. Yao et al. prepared a P doped nickel telluride electrocatalyst containing Te vacancies anchored on corn straw-derived carbon (MSC/P < NiTe2-x), which served as a functional layer for high-performance LSBs separators [155]. XANES spectra and Fourier-transform k3-weighted EXAFS spectra confirmed the modulation of electronic states within Ni by Te vacancies and P doping (Fig. 10a). Electrochemical analysis revealed that the P < NiTe2-x electrocatalyst improved the intrinsic conductivity of LiPSs, enhanced the chemical affinity for LiPSs, and therefore accelerated the redox conversion of sulfur. Shi et al. regulated the performance of the CCMs by simultaneously introducing nitrogen doping and selenium vacancy into a conventional MoSe2 electrocatalyst, which aimed to selectively catalyze the nucleation and dissociation of Li2S, thereby enhanced the bidirectional sulfur conversion activity [156]. The dual-defect engineering strategy not only unveil the crucial role of defects in accelerating the oxidation–reduction of Li2S but also provide a universal roadmap for designing electrocatalysts with more than one active site (Fig. 10b).

|

Download:

|