b Institute of Materials Science and Devices, Suzhou University of Science and Technology, Suzhou 215009, China;

c Faculty of Materials Metallurgy and Chemistry, Jiangxi University of Science and Technology, Ganzhou 341000, China;

d Fujian Provincial Key Laboratory of Eco-Industrial Green Technology, Key Laboratory of Green Chemical Technology of Fujian Province University, College of Ecological and Resources Engineering, Wuyi University, Wuyishan 354300, China

As an important material basis for human survival and development, fossil energy supports the progress of human civilization and the development of economy and society in the past two hundred years [1]. The large consumption of human beings and the non-renewable fossil energy leads to the emergence of energy crisis. Energy storage has become a great challenge for human beings in the 21st century. It is determined to develop energy storage devices with low cost, low carbon emission and environmental protection [2–5]. Supercapacitors can be traced back to the 1970s [6]. They have a larger specific surface area, and their capacitance is greatly improved compared with the traditional ones. They have fast charge and discharge speed, long cycle life, high power density, low environmental pollution, and wide operating temperature range [7]. Supercapacitors are composed of electrodes, electrolyte solutions, separators, and current collectors. According to the energy storage mechanism, supercapacitors can be divided into electric double layer supercapacitors, pseudocapacitance supercapacitor, and hybrid supercapacitors. There is no chemical reaction in the electric double layer supercapacitor. When two electrodes are inserted into the electrolyte at the same time and a voltage smaller than the decomposition voltage of the electrolyte solution is applied between them, the positive and negative ions in the electrolyte will move rapidly to the two poles under the action of the electric field, and form a close charge layer on the surface of the two electrodes respectively, relying on the electrostatic adsorption of ions occurring simultaneously at the positive and negative poles for energy storage. Pseudocapacitive supercapacitors undergo potential deposition through electroactive substances, and reversible chemical adsorption, desorption or redox reactions occur not only on the surface of the electrode, but also inside the entire electrode. Therefore, they can obtain higher capacitance and energy density than electric double layer capacitors. The formation of hybrid supercapacitors originates from the coupling of different redox pseudocapacitive materials (such as metal oxides and conductive polymers) and electric double layer materials (such as graphene and activated carbon). The energy storage principle depends on the combination of electric double layer and pseudocapacitive energy storage mechanism. The performance of the supercapacitor is related to the electrode material, the electrolyte and the separator used, and the electrode material is the key to determine the capacitance performance. Because it is an important support for supercapacitors, the performance of electrode materials directly affects the performance of capacitors. At present, there are three main types of materials as supercapacitor electrodes: carbon materials, metal oxides and conductive polymers [8–12]. Carbon-based electrode has the advantages of low cost, good conductivity and good stability. With the increasing demand for human survival and development, it is urgent to seek a renewable energy to replace traditional fossil energy. Biomass has great potential as the only energy source that can replace fossil fuels under current energy constraints. Bilgili et al. [13] proposed several advantages of these promising biomass energy: (1) Good technical and economic credibility; (2) Abundant reserves; (3) Biomass resources help to solve energy dependence and national energy security problems by minimizing energy demand; (4) Biomass reduces poverty by improving the agricultural economy, increasing employment in rural areas. It promotes economic growth by developing industry. Therefore, developed countries tend to promote the use of biomass; (5) Biomass is effective in solving global problems such as global warming, climate change, air pollution and acid rain.

Biochar is generally prepared by carbonization of photosynthetic organic agricultural and forestry wastes (such as straw [14], grape [15], chestnut [16], wood [11,17,18], wheat bran [19], fruit core [16], and pollen [20]). The prepared biomass-derived carbon material is a widely used supercapacitor electrode material, which has the advantages of large specific surface area, developed pore structure, excellent conductivity, light weight and low cost [21–23].

The preparation of biomass porous carbon materials mainly includes: first, the raw materials are screened, and the required materials are finally prepared by high temperature carbonization and activation after pretreatment. Among them, activation refers to the reaction between biomass raw materials or precursors and activators, which causes partial carbon atoms to ablate and gasify, resulting in a large number of pores. The original pores will further expand, and even merge between pores, resulting in more complex pore structure of the material. Activation is the key to regulate the pore structure of carbon materials, which will directly affect the electrochemical and adsorption properties of porous carbon materials. Biochar has a variety of pore size distribution, including macropores (pore size greater than 50 nm), mesopores (pore size 2–50 nm) and micropores (pore size less than 2 nm) [24]. A large number of micropores provide abundant accumulation space for electrons, and play an important role in the adsorption/desorption process of charge through controlled diffusion and molecular sieve effect. Both macropores and mesopores provide channels for the transport of ions and charges. The mesopores shorten the diffusion distance of ions and reduce the diffusion resistance, so that ions can easily penetrate into the internal micropores. The large channel acts as a buffer ion storage layer, which helps the ion transport [25,26]. Improper pore structure matching of carbon materials will directly lead to the blockage of ion transport channels and low charge and discharge performance at high current [27]. Regulating the porosity and structure of biochar materials can improve the transmission efficiency of electrolyte ions, which is of great significance for improving the electrochemical performance of electric double layer supercapacitors. Therefore, it is necessary to study the activation mechanism during the preparation of porous carbon.

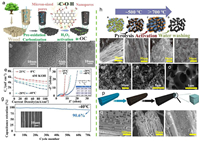

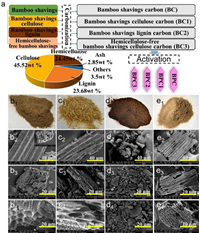

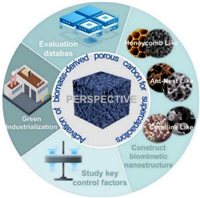

In this paper, the activation methods applied to the preparation of biomass porous carbon in recent years are summarized as shown in Fig. 1, including traditional physical activation, chemical activation and some unconventional activation methods. The action principle and future development direction of activators are systematically reviewed.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. An overview of activation of biomass-derived porous carbon for supercapacitor. | |

The traditional activation methods of biomass porous carbon are mainly divided into physical activation and chemical activation.

2.1. Physical activationPhysical activation method refers to a method that uses oxygen containing gas such as water vapor, flue gas or air as an activator to react with atoms inside carbon materials at high temperatures. Physical activation can be divided into three steps: First, the removal of clogged adsorption media; Secondly, the pores formed in the precursor material are expanded; Finally, new pores are formed by selective oxidation of the carbon precursor.

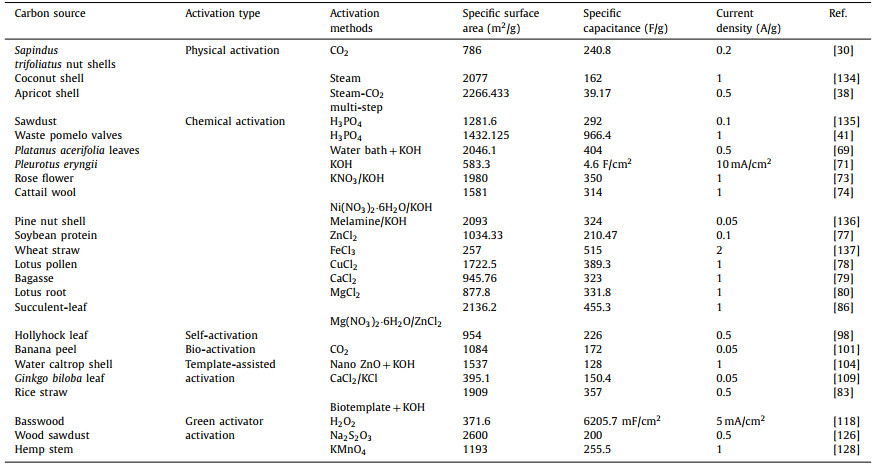

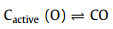

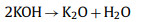

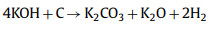

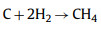

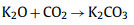

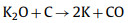

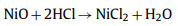

With the official launch of the carbon market, the management of carbon dioxide emissions has become more stringent, and the resource utilization of carbon dioxide has gradually received attention. CO2 can be used as an activator. When CO2 diffuses into the pores and is adsorbed on the active sites of biochar, partial gasification occurs. The activation mechanism is as follows:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Rawat et al. [28] prepared biochar from litchi seeds and studied its application in supercapacitor electrodes. A symmetric supercapacitor using biochar obtained at 700 ℃ achieved a specific capacitance of 190 F/g at a current density of 1 A/g. After CO2 activation, the capacitance increased significantly to 493 F/g. The charge-discharge cycle stability of the activated biochar supercapacitor is well maintained, and the capacitance retention rate is higher than 90% after 10, 000 charge-discharge cycles in 1 mol/L H2SO4 electrolyte. The energy and power density of the water-based symmetric supercapacitor prepared using activated biochar are 24.6 Wh/kg and 0.6 kW/kg, respectively. Murugan Vinayagam et al. [29] took Syzygium cumini fruit shells (SCFS) and Chrysopogon zizanioides roots (CZR) as raw materials, carbonized them and placed them in a tube furnace, and then injected CO2 into N2 atmosphere for activation. SCFS carbon source samples showed microporous characteristics, while CZR carbon source samples showed mesoporous characteristics. The formation of CSR-AC mesopores was attributed to the higher ash content of CZR, and the ash was activated and removed by CO2 to form mesoporous structure. SCFS-AC has a high specific surface area, pore volume and pore size, in which the micropore structure contributes to the specific surface area and provides abundant ion adsorption sites, while mesoporous and macroporous structures reduce the resistance of ion transport and shorten the diffusion distance. Murugan Vinayagam et al. [30] further selected a kind of nut shells as raw materials and carbonized them into CO2 for activation. FE-SEM technology showed disordered channel-like surfaces with pores, and physical activation could also improve the activity of porous carbon materials by forming additional pores inside carbon particles. The material has a specific surface area of 786 m2/g, a pore volume of 0.212 cm3/g, and a specific capacitance of 240.8 F/g at 0.2 A/g. It remains at 65.6 F/g at a high current density of 2.0 A/g. The diffusion rate of porous carbon materials using CO2 as activator is slow, and the activation process is easy to control, but it also leads to a higher activation temperature required, generally between 850 ℃ and 1100 ℃. Moreover, due to the large diameter of carbon dioxide molecules, the pore size distribution is relatively narrow.

Steam is also often selected for physical activation. Porous carbon materials with steam as activator have fast thermal motion, wide pore distribution and uniform pore size, and are easy to operate and environmentally friendly. In the activation process, water vapor is adsorbed on the carbon surface and releases hydrogen and oxygen. The presence of hydrogen prevents the continuous reaction of the active site, and the released oxygen further reacts with carbon monoxide separated from the carbon surface to form carbon dioxide [31]. At the same time, a large number of micropores were produced [32]. Although the detailed mechanism of water vapor activation is still unknown, it is known that the optimum temperature of its activation is 750–900 ℃ [33]. Within this temperature range, sufficient heat can be guaranteed for the reaction of carbon materials with water vapor, and the water vapor can be uniformly diffused in the carbon. Pundita Ukkakimapan et al. [34] took sugarcane leaves as raw material. After carbonization at 500 ℃ in N2 atmosphere, ball milling was carried out before steam activation. Due to physical activation, carbon on the surface was removed non-selectively, and the porous structure of the prepared sample was distributed on the surface. However, its higher mesoporous ratio and larger average aperture result in higher specific capacitance. Qin et al. [35] used pine nut shell as carbon source to prepare activated carbon through steam activation, and explored the influence of activation temperature, activation time and steam flow rate on sample preparation. Finally, activated at 850 ℃ for 60 min, the sample prepared with steam flow rate of 18 mL/h had a specific surface area of 956 m2/g and a mesopol ratio of 37.1%. It has an interconnected layered pore structure.

Although both CO2 and steam have certain disadvantages as activators alone, they complement each other, and it is not easy to obtain an environment where only steam or CO2 exists. When biomass raw materials decompose under certain conditions, a certain amount of CO2 and steam will be produced. Therefore, Mai et al. [36] studied the effects of CO2 and steam activation and co-activation on the physical and chemical properties of activated carbon prepared from linear ferns. Among them, the stems and leaves of linear ferns have a highly porous structure, which is conducive to faster and more uniform dissemination of heat, and have a higher fixed carbon content, which makes it a promising material for preparing biochar. Steam activation produced a higher specific surface area (1015 m2/g), while CO2 (653 m2/g), and both gases alone formed micropores on the carbon. When the steam concentration increased, with the increase of pore formation, only mesopores were observed using steam, because steam stopped the formation of micropores after the early stage of the activation process, and then converted the pores into mesopores by expanding the width of the pores, resulting in a significant decrease in the micropore rate [37]. The combination of CO2-steam mixed atmosphere and high temperature proved to be a suitable environment to promote the formation of highly porous coke, and proved to adjust the performance of activated carbon by simply adjusting the ratio of water vapor and CO2. Considering the complexity of the physical activation process, the effects of other factors such as heating rate, activation temperature, activation time or the interaction between them on the performance of activated carbon need to be further studied. Ding et al. [38] also used the combination of steam and CO2 as the activator and apricot shell as the precursor. Firstly, water vapor was injected into the apricot shell for pre-activation, generating abundant micropore structure, which improved the diffusion rate of CO2, and then CO2 was injected into the apricot shell for activation. The main chemical reactions that occur are as follows:

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

The obtained samples have high specific surface area and pore volume, and the effective pore volume and mesoporous volume fraction are 0.720 cm3/g and 55.76%, respectively.

Air as a gaseous oxidant can also be used as an activator for the activation of porous carbon. However, it reacts more positively with carbon, resulting in wear and tear within the pore structure [39], resulting in lower product yield, and requires higher activation temperatures than CO2 and water vapor when activated by air.

The selection of appropriate activation temperature in physical activation determines whether porous carbon materials can be successfully prepared. The reactions that occur are endothermic reactions. Compared with chemical activation, higher reaction temperature and 2–3 times reaction time are usually required. Although the physical activation method does not require corrosive and expensive chemical reagents as activators, the production cost is low, more environmentally friendly and simple to operate, but it is difficult to accurately adjust the activation process, and the porous structure is relatively disordered. Therefore, in recent years, the study of biomass porous carbon by physical activation methods has become increasingly unpopular.

2.2. Chemical activationChemical activation method refers to the reaction of chemical activators (such as sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide and phosphoric acid) with raw materials under high temperature conditions. The detachment of carbon atoms and the escape of gas generated by the reaction lead to the formation of abundant pore structures in the activated carbon skeleton. The mechanism of chemical activation and the properties of the product depend largely on the type of activator. The activator mainly dehydrates or erodes the raw materials and then creates pores.

Phosphoric acid is one of the commonly used acid activators, which belongs to a kind of weak acid. The activation step of phosphoric acid as an activator is mainly divided into two steps. The first step is to depolymerize cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin. and form crosslinking between polymers through dehydration and condensation reaction. Subsequently, phosphate and polyphosphate further cross-linked polymer fragments to form porous structures. It has the advantages of recyclability, low cost and environmental friendliness. Lin et al. [40] used sawdust as raw material and used phosphoric acid as activator by one-step carbonization activation method. The addition of phosphoric acid inhibited the formation of tar and protected the carbon skeleton. The prepared porous carbon had rich microporous structure. The optimal carbonization activation temperature was further explored: at 900 ℃, the prepared porous carbon has the largest specific surface area (1281.6 m2/g) and the highest total pore volume (0.638 cm3/g). Huang et al. [41] used pomelo valves as raw material, after simple carbonization, using H3PO4 as activator, after hydrothermal activation, the carbonized tissue was composed of a large number of uniform mesopores and micropores, which was conducive to ion transport. The activation of phosphoric acid can promote the formation of thin carbon sheets and porous structures. Under the transmission electron microscope, many 1–3 nm nanopores can be seen, and many amorphous carbon particles with a diameter of about 20 nm are closely connected to effectively promote the diffusion of electrolyte ions. The prepared layered porous carbon electrode has a high specific capacitance of 966.4 F/g at 1 A/g, and has an ultra-high stability of 95.6% even after 10, 000 cycles.

Oluwatosin Oginni et al. explored the preparation of porous carbon by one-step activation method and two-step activation method respectively. One-step method is to activate the biomass impregnated with activator; the two-step method is to carry out high-temperature carbonization first, and then to carry out high-temperature activation after impregnation and drying in the activator. Compared with the two-step method, its specific surface area is larger and the total pore volume is higher. A large number of micropores and mesopores may be the reason for the high specific capacitance, micropores are also formed on the wall of mesopores [42]. The preparation of porous carbon by two-step activation method can obtain by-products such as charcoal and coke wood liquid, and the overall utilization rate can be improved and the economic efficiency is high. Therefore, Hu et al. [43] used lacquer wood as raw material and phosphoric acid as activator to further explore the effects of activation temperature and process. When porous carbon was prepared by one-step method, glycosidic bonds were hydrolyzed due to the impregnation of phosphoric acid and the cracking of aromatic ether bonds in lignin. At the same time, phosphoric acid acts on the organic matter in the precursor to form polyphosphoric acid groups and phosphates, which promotes the precursor to expand into the porous structure together with the acid. It was found that with the increase of activation temperature, the degree of graphitization increased and the conductivity increased. However, when the activation temperature is too high, reaching 800–900 ℃, the oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface of porous carbon disappear, resulting in a decrease in the improvement of pore channels and a decrease in specific heat capacity. When the activation temperature is 400 ℃, it has the best specific surface area. When the activation temperature is 600 ℃, it has a longer discharge time and a larger specific capacitance. Zhao et al. [44] used chinar fruit fluffs as raw material and phosphoric acid as activator to explore the optimal activator dose and activation temperature. When 30 wt% H3PO4 was selected as the activator, the porous carbon obtained at 600 ℃ had the best specific surface area of 1758.5 m2/g, and the porous carbon is mainly mesoporous structure, which can not only reduce the resistance of ion transmission, but also serve as a channel for ion transport. The construction of porous carbon materials with mesoporous structure has research prospects.

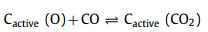

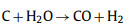

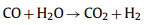

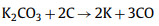

In the activation of biomass porous carbon, alkali is commonly used as an activator and KOH is preferred. The activation mechanism is as follow:

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

|

(10) |

|

(11) |

|

(12) |

|

(13) |

|

(14) |

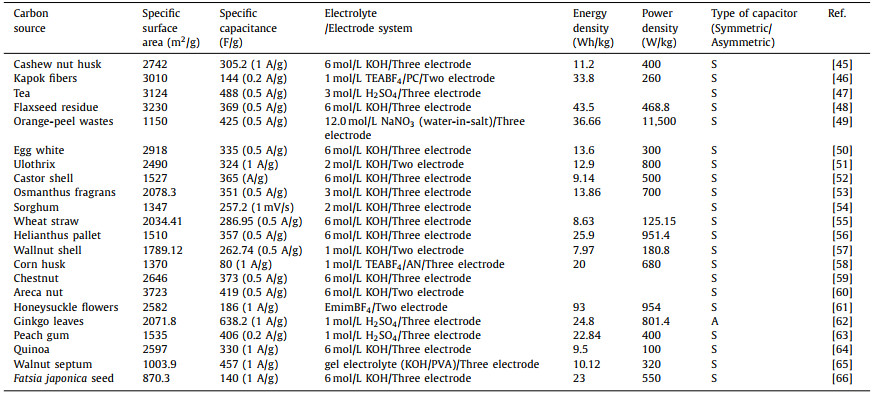

Firstly, KOH dehydrates with carbon and hydrocarbons in raw materials at low temperature. As the reaction proceeds and the temperature rises, the produced H2O molecules enter the pores of the carbon and further react with water gas to form a small amount of CO, CO2, H2 and other gases, and a small amount of CH4 may also exist. In this process, C atoms are consumed, and a large number of pores are formed when the generated gas molecules escape from the surface of the material. When the temperature reaches 500 ℃, the non-carbon elements in the material volatilize and produce tar. When the temperature reaches 600 ℃, KOH completely reacts, and K element mainly exists in the form of K2CO3 and K2O. As the temperature continues to increase, K2CO3 and K2O continue to react with C to form K element. When the temperature reaches the boiling point of K element at 723 ℃, K element escapes or diffuses into the carbon matrix in the form of vapor. Table 1 summarizes the electrochemical properties of porous carbon electrode prepared by KOH as activator [45–66].

|

|

Table 1 Porous carbon materials prepared by KOH as an activator and their electrochemical performance in supercapacitors. |

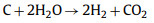

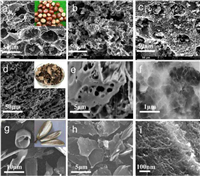

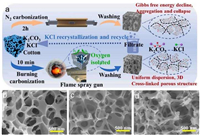

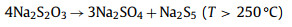

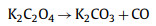

Porous carbon materials were prepared by chemical and physical activation of chestnut seeds with KOH and carbon dioxide at 800 ℃. In terms of specific surface area, compared with that before activation (17.1 m2/g), the specific surface area and total pore volume increased significantly after physical activation (105.7 m2/g) and chemical activation (1221.2 m2/g). The pore structure under scanning electron microscope is shown in Figs. 2a–c. Electrochemical analysis results show that the discharge capacitance of chemically activated carbon (173 F/g) is 157% higher than that of CO2 activated carbon (67.30 F/g) and 3 times higher than that of non-activated carbon (57.4 F/g) at a low current density of 0.1 A/g [67]. Cai et al. [45] used cashew nut shells as raw materials, and used KOH as an activator in an argon atmosphere at 850 ℃, and activated them after heat treatment in an inert gas flow of 600 ℃. After KOH activation, the original hierarchical structure was retained well (Figs. 2d and e). Many new pores appeared in the sample, and the original pore structure was further merged and expanded (Fig. 2f). The specific surface area and pore structure were greatly improved, and the mesoporous amount in the sample increased with the increase of KOH ratio, which was helpful for the diffusion of ions in the electrolyte. The prepared porous carbon exhibits a high specific surface area of 2742 m2/g and a total pore volume of 1.528 cm3/g. It exhibits a high specific capacitance (305.2 F/g) and good rate capability in a three-electrode system (256 F/g at 20 A/g). Zou et al. [46] made the precursor, kapok fiber, and dewaxing through low-temperature pre-carbonization treatment to promote the wettability of subsequent KOH on the carbon precursor, and prepared a carbon sheet with a specific surface area of 3010 m2/g, a pore volume of 2.756 cm3/g, and an ultra-high mesoporous volume ratio. The kapok fiber directly carbonized at 850 ℃ shows a thin-walled tubular structure (Fig. 2g). After carbonization and KOH activation, the tubular fibers break into sheets with a plane size mostly less than 20 μm as shown in Fig. 2h. By observing the surface of the carbon sheet more carefully, the porous structure with abundant nanopores was clearly observed (Fig. 2i). In organic electrolytes, it shows a high specific energy density even at high power. it shows a high specific energy density even at high power. Zhu et al. [47] extracted helical carbon fibers from tea by a non-catalytic strategy, and further prepared helical porous activated carbon fibers by KOH activation. The special helical porous structure provides defect sites and high nanoporous rate. Compared with the samples prepared with K2CO3 and ZnCl2 as activators, KOH destroyed the graphite crystallite structure in the carbon fiber during the activation process, and the small graphite grains had rich edge positions, which was beneficial to the dispersion of electrolyte ions. The final sample has an ultra-high specific surface area (3124 m2/g) and pore volume (1.6 m3/g). The specific capacitance is 488 F/g at 0.5 A/g in the three-electrode system and 187 F/g at 1 A/g in the two-electrode system. Li et al. [68] used pine nut shell as raw material. After pre-carbonization treatment, the pre-carbonized sample was mixed with potassium hydroxide and urea in a mass ratio of 1:1:1, and nitrogen atoms were introduced. The sample was activated at a heating rate of 3 ℃/min in nitrogen at 600–800 ℃. It was found that the specific surface area of the material can be well controlled by controlling the activation temperature. When the temperature is 700 ℃, the specific surface area of the material is as high as 2192 m2/g. When the current density is 0.5 A/g, the specific capacitance is 408 F/g, and after 5000 cycles of testing, the specific capacity retention rate is as high as 95%. The successful doping of nitrogen forms four carbon-nitrogen bonds: pyridine nitrogen, pyrrole nitrogen, graphite nitrogen and nitrogen oxide. The graphite nitrogen atoms are connected to the three carbon atoms in the graphite carbon skeleton, increasing the additional free electrons, thereby increasing the conductivity of the carbon material, because most of the graphite nitrogen atoms are located in the graphite carbon plane, breaking the degree of graphitization; pyridine nitrogen is a nitrogen connected between two carbon atoms on the edge of graphene. It has unhybridized lone pair electrons and strong electron donating ability. Pyrrole nitrogen refers to the nitrogen atom in the five-membered C—N heterocyclic structure of nitrogen-doped carbon materials, which is very unstable. The pyridine and pyrrole nitrogen atoms located at the edge of the carbon layer will introduce a large number of surface defects, forming a disordered honeycomb carbon structure, which is more effective in adsorbing heteroatoms and improving electron storage capacity. Li et al. [48] used flaxseed residue as raw material. After carbonization in argon atmosphere, KOH was used as an activator, which was used as an excellent activator for micropores. The prepared samples were mainly micropores. The specific surface area was large, up to 3230 m2/g. More than 70.1% of the micropore volume was contributed by larger micropores (1–2 nm). Large micropores can achieve high charge storage capacity and ensure rapid ion transport, thereby increasing the energy density of supercapacitors without sacrificing high power density. When the current density is 1 A/g, the specific capacitance is 408 F/g, with excellent rate and cycle performance. Even at a high current density of 20 A/g, more than 92.7% of the initial capacitance can be retained. After 10, 000 cycles in KOH electrolyte, the capacitance retention rate exceeds 98.1%.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. SEM images of (a) raw biochar and a photograph of chestnut seed (inset), (b) biochar after physical activation, and (c) biochar after chemical activation. Reproduced with permission [67]. Copyright 2020, MDPI. (d-f) SEM images of cashew nut husk biomass-derived porous carbon. Reproduced with permission [45]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (g) SEM images of the kapok fibers directly carbonized at 850 ℃ and a photograph of a broken kapok fruit (inset), and (h, i) the activated kapok fibers with a KOH mass ratio of 2 to the pre-carbonized kapok fibers. Reproduced with permission [46]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. | |

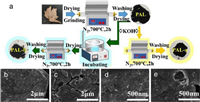

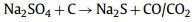

Ceren Karaman et al. used orange peel as precursor to carbonize at 400 ℃ in nitrogen atmosphere, then activated in KOH solution and annealed at 800 ℃ for 2 h (Fig. 3a). By adjusting the ratio of potassium hydroxide, the porous carbon material with the best electrochemical performance was prepared with the highest specific surface area (1150 m2/g) and the largest pore volume (991 cm3/g). When KOH is introduced into waste orange peel as an activator, the synthesized graphene-like porous carbon network exhibits a three-dimensional honeycomb structure composed of interconnected micropores and mesopores (Figs. 3b–d). This unique arrangement essentially prevents the restacking/agglomeration of nanosheets. During the activation process, due to the melting of potassium hydroxide and the cleavage of chemical bonds, the insertion of ions into the carbon layer promotes the formation of an interconnected network. Moreover, due to the catalytic gasification of carbon and the insertion and rapid removal of carbon interlayer ions, the mesoporous structure is likely to be generated [49]. Yang et al. [50] used egg white as raw material, which was fully activated in KOH aqueous solution after freeze-drying and carbonization. The etching of KOH led to the formation of a three-dimensional honeycomb structure, which contributed to the full activation of active substances. The prepared material had a large specific surface area (2918 m2/g), a high specific capacity of 335 F/g in 6 mol/L KOH electrolyte, superior rate performance (240 F/g at 20 A/g) and cycle performance (91.7% capacitance retention after 10, 000 cycles). At the same time, it was found that with the continuous increase of potassium hydroxide content, the corrosion performance was enhanced and the pore structure was destroyed. An appropriate amount of KOH as an activator was beneficial to the diffusion of electrolyte ions. Liu et al. [51] selected filamentous algae as raw materials, the raw materials are filamentous, and the carbon loss is less during the heating process (Fig. 3e), which can better maintain the original morphological map (Figs. 3f and g), and is a high-quality natural template that can be used. The synthesis process of porous carbon is relatively simple. After pyrolysis in an inert atmosphere at 500 ℃, KOH was selected for activation without adding additional template material. The samples show many irregular small particles with layered pore structure, and different sizes of pores and channel in Fig. 3h can be found. The specific surface area of the prepared sample is up to 2490 m2/g, and the optimum ratio of KOH activator to sample is explored. When the mass ratio of sample to KOH powder is 1:2, the prepared porous carbon material has the largest specific capacitance (324 F/g at 1 A/g).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis pathway for the orange-peel wastes-derived porous carbon. (b-d) SEM images of orange-peel wastes-derived porous carbon. Reproduced with permission [49]. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. (e) Illustration of the synthesis process of biomass-derived sulfur-doping porous carbon. (f–h) SEM images of biomass-derived sulfur-doping porous carbon. Reproduced with permission [51]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. | |

In addition to the type of activator, the activation method and activation conditions are also important. The activation method used for the same activation reagent will affect the electrochemical performance of the prepared electrode material. After conventional carbonization of Alsophila spinulosa leaves, Weng et al. [69] mixed with potassium hydroxide and water and incubated in a water bath at 60 ℃ for 1 h before activation in a tube furnace (Fig. 4a). It can be seen from the SEM (Figs. 4b–e) that after the carbon material is immersed in the potassium hydroxide solution during the incubation heating process, some small potassium hydroxide particles are adsorbed on the surface of the carbon material, which is more conducive to the activation of potassium hydroxide. The samples (Figs. 4c and e) incubated in advance have many silts and small pores, which make the pore structure of the samples richer and promote the increase of pore volume [70], which is conducive to the migration of electrolyte ions. The specific surface area (297.22 m2/g) of the sample prepared by direct carbonization is very small. The total pore volume (1.1079 cm3/g) is also very small, indicating that direct carbonization cannot obtain the large specific surface area required for the capacitor material. After activation with potassium hydroxide alone, the specific surface area increased to 1766.1 m2/g, and the specific surface area after incubation heating treatment was higher, reaching 2046.1 m2/g. More microporous structures can be produced by water bath incubation.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Diagram of the preparing process for biomass carbon materials from waste Platanus acerifolia leaves for supercapacitor. (b–e) SEM images of prepared samples. Reproduced with permission [69]. Copyright 2021, Springer Heidelberg. | |

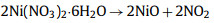

The porous carbon materials prepared above are powder-like, and the powder-like structure limits its development to a certain extent. First, it is necessary to use an additional binder to fix the porous carbon material on the conductive current collector, which reduces the available effective surface area. Secondly, the adhesion of the fixed surface is low, which greatly reduces the cycle stability of the supercharge. Finally, the mass load of the powdered carbon active material coated on the conductive substrate is usually too low to meet the actual demand. Cui et al. [71] selected Pleurotus Eryngii as a raw material and prepared a three-dimensional heteroatom-doped self-supporting porous carbon film by a two-step pyrolysis method (Fig. 5a). Among them, KOH not only acts as an activator to etch a large number of disordered micropores and mesopores during high-temperature pyrolysis (Figs. 5b and c), but also maintains the original macroscopic structure during the freeze-drying process of KOH-treated slices, which is essential to prevent the initial structure from being destroyed during subsequent pyrolysis. The free-standing carbon film prepared by two-step pyrolysis has a weight loss of 75.1%, indicating that it has high porosity. In addition, various aqueous groups in the electrode give the electrode a higher electrolyte wettability. The wettability test (Figs. 5d1 and d2) shows that the electrolyte droplets can quickly diffuse on the electrode surface and quickly enter the pores with a certain contact angle, and also provide additional redox pseudocapacitance sites. The excellent capacitance performance (Figs. 5e and f) of the electrode can be attributed to its large specific surface area, high porosity, and excellent electrolyte wettability. The large specific surface area and high porosity maximize the adsorption of electrolyte ions, and the excellent electrolyte wettability ensures the rapid transport of electrolyte throughout the electrode.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Schematic diagram illustrating the synthesis of Pleurotus Eryngii carbon membrane (PECM) electrode and the assembled PECM-based aqueous symmetric SCs. (b) Side-view SEM images of PECM. (c) Top-view SEM images of PECM-800 electrode. (d1, d2) Electrolyte wettability of PECM electrode. (e) GCD curves for PECM-based SCs. (f) Nyquist plots of PECM-based SCs electrode. Reproduced with permission [71]. Copyright 2019, Wiley. | |

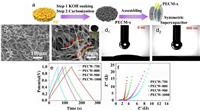

However, the use of KOH as an activator alone will lead to the loss of heteroatoms [72]. In order to improve the electrochemical performance of the electrode, the mixed activation of the two activators is considered. Pan et al. first converted dry roses into biochar by simple carbonization. Then, the obtained biochar was activated by a mixture of KOH and KNO3 under N2 atmosphere, and the gas by-products such as H2 and CO were released during the activation process to form a well-organized layered porous structure. The obtained porous carbon material still maintains its original interconnected layered structure after the activation process. The prepared material has a large specific surface area (1980 m2/g) and good cycle stability. After 140, 000 cycles at 100 A/g, the capacitance decay rate is only 4.4% [73]. Su et al. [74] used Cattail wool as raw material. Firstly, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was used as activator for pre-activation at 600 ℃, and then KOH was used as activator for secondary activation at 800 ℃. Under the action of high temperature calcination and KOH chemical activation, the hollow tubular structure becomes brittle, easy to break into short tubes, and the pore structure is less. Ni(NO3)2·6H2O was added as activator, and there were abundant pore structures on the surface, which mainly came from the decomposition of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O:

|

(15) |

|

(16) |

When the weight percentage of Ni(NO3)2·6H2O is 10%, the capacitance performance is the best. In the three-electrode system, when the current density is 1.0 A/g, it has a high charge storage capacity and a specific capacitance of 314 F/g. In addition, Zhang et al. [72] selected KOH and Na2S co-activation with wheat bran as raw material, and their specific surface area increased (1585.5 m2/g), pore volume increased (0.977 cm3/g) and pseudocapacitance contribution increased. The prepared sample has 488 F/g at 1 A/g and good rate performance.

The main components of some biomass raw materials are cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin, and the stability varies greatly under activation. If KOH activation is not enough to etch the stable part, only a few microns of traditional activated carbon particles can be produced. Therefore, Guan et al. [68] used melamine and KOH as activators to activate pine nut shells. Melamine will be converted into g-C3N4, which is decomposed into NH3, C2N2+, C3N2+ and other highly active components, which can effectively etch the stable part. The co-activation of melamine introduces N atom doping, in which pyridine nitrogen and graphite nitrogen help to accelerate ion transfer. Pyridine nitrogen and pyrrole nitrogen content is higher, accounting for 70%, which can provide additional Faraday capacitance in alkaline solution. Among the prepared samples, although the specific surface area (1847 m2/g) of the porous carbon material prepared when the mass ratio of pine nut shell, KOH and melamine is 1:3:1 is not the largest, its electrochemical performance is the best due to its high content of pyridine nitrogen and pyrrole nitrogen. The specific capacitance is 324 F/g at 0.05 A/g, and the cycle stability is 94.6% after 1000 cycles at 2 A/g. He et al. [75] also used KOH and melamine as dual activators to activate taro stems, and the prepared samples had a higher nitrogen content (4.8%), of which graphite nitrogen content (2.65%) accounted for the largest proportion, followed by pyridine nitrogen (1.61%). The porous carbon material has a high specific capacitance (236.4 F/g at 0.1 A/g) and excellent long cycle durability (89.3% retention after 10, 000 cycles at 20 A/g).

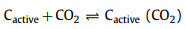

In the field of biomass porous carbon activation, apart from acid and base as activators, metal salts as activators have been gradually studied. Commonly used activators are mainly chloride, potassium carbonate, potassium nitrate and so on.

Unlike KOH, ZnCl2 as an activator does not directly react with carbon raw materials, and it mainly removes oxygen by dehydration. The reaction can be divided into three stages according to the temperature: when the temperature is below 327 ℃, the oxygen-containing groups in the molecule undergo condensation reaction, accompanied by the breakage of molecular bonds, reducing the number of hydroxymethyl and phenolic hydroxyl groups; when the temperature is 327–700 ℃, the intramolecular reaction continues, the molecular structure is rearranged, and the carbon skeleton is initially formed; when the temperature is below 900 ℃, small molecules such as methane, formaldehyde, water and CO are generated. At the same time, the impregnation effect of ZnCl2 forms voids between the carbon layers and forms a microporous structure. Ye et al. [76] used corn husk as raw material, first carried out hydrothermal carbonization, added potassium salt as catalyst, and then added ZnCl2 as activator to explore the optimal activation temperature. ZnCl2 first reacts with water to form Zn2OCl2·2H2O. Zn2OCl2·2H2O decomposes at high temperature to form ZnCl2 gas and ZnO. ZnCl2 gas escapes to form a large number of mesopores and a small amount of micropores. However, the addition of potassium salt will also change the pore structure. At about 600 ℃, ZnCl2 is mainly used as an activator to play a pore-forming role. When the temperature rises to 800 ℃, the potassium salt reacts with carbon to form CO2 and CO, forming a large number of micropores. Feng et al. [77] prepared nitrogen and oxygen co-doped porous carbon sheets by one-step carbonization activation method using soybean protein as raw material and ZnCl2 as activator. With the addition of activator, the microstructure of amorphous carbonaceous products changes from irregular bulk particles to flakes. With the increase of zinc chloride content, the porosity of the carbon sheet changes from micropore to layered porous structure, and the addition of ZnCl2 increases the doping rate of nitrogen and oxygen elements. The maximum energy density of the final sample material is 16.27 Wh/kg, and the maximum power density is 8.44 kW/kg.

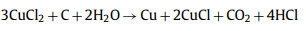

Considering that FeCl3 is also an effective activator, Mehrnaz Ebrahimi used FeCl3 to activate barley straw. The prepared samples have rich pore structure, and a small part of the porous structure comes from the reaction of FeCl3 and N—O substances in the pre-carbonized samples to form FeOCl and C3N4, mainly from the further decomposition of FeOCl. The etching reaction between Fe and carbon will also consume part of the carbon sample, and the resulting carbon iron will produce additional pores after being washed with acid. In a potassium hydroxide electrolyte, the prepared electrode in a three-electrode cell at a current density of 2 A/g. Compared with the porous carbon obtained by traditional ZnCl2 and FeCl3 activation, the following reaction occurs using CuCl2 as an activator [78]:

|

(17) |

|

(18) |

The mild interaction between copper chloride and carbon network caused weak structural damage, resulting in the uniform distribution of worm-like pores on the surface. The prepared layered porous carbon had higher yield, larger specific surface area and more developed pore structure. It has been reported that CaCl2 was used as a biological activator instead of traditional activator to prepare porous carbon materials for ion adsorption. Liu [79] used CaCl2 to activate and crack bagasse in one step, which played a prominent role in improving the specific surface area and pore structure of biomass carbon materials, and introduced abundant nitrogen atoms while creating pores to realize the preparation of nitrogen-rich porous materials. Liu selected urea as the nitrogen source, and had the effect of stretching the carbon layer and expansion. With the increase of temperature, the urea hydrolysis product and CaCl2 fully diffused and filled in the skeleton, and the initial crystal structure of bagasse was destroyed. The highly uniformly dispersed activator aggregates and precipitates to form a crystalline structure CaCl2·2H2O. Finally, the inorganic salts in the pores are removed by repeated washing with hydrochloric acid and water.

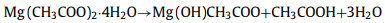

Zhong et al. [80] considered that Mg and Ca belong to the same group of elements, and using MgCl2 as an activator should also have a good catalytic effect. Therefore, lotus root was used as raw material and MgCl2 was used as an activator. During the reaction, MgCl2 was decomposed to form Mg (OH)Cl, which catalyzes the dehydrogenation, decarboxylation and crosslinking reaction of raw materials. The decomposition of volatile organic compounds can effectively inhibit the coking that may block pores. At temperatures above 500 ℃, magnesium chloride is directly decomposed into magnesium oxide, the carbon precursor is further gasified, and the remaining magnesium oxide is used as a template to form a pore structure. The porous carbon material has high specific capacitance and good durability (98% after 10, 000 constant charge and discharge cycles in a two-electrode system).

These activators are considered to be toxic chemicals or some require special activation conditions. Complex preparation processes will limit the use of these activators, and some nontoxic activators have attracted attention. Among nontoxic activators, potassium acetate has the advantages of easy availability, low cost, and easy solubility in water and ethanol. In addition, the mild potassium acetate etching also retains the natural structure of the material and does not destroy too many pore structures when activated. Xu et al. [81] prepared a layered porous carbon by one-step carbonization method using biomass tar as raw material and potassium acetate as activator. The specific capacitance was as high as 261.7 F/g at 1 A/g, and the capacitance retention rate was 91% after 5000 cycles at 5 A/g, which not only treated the harmful biomass tar inevitably produced in the biomass gasification process. It also provides another solution for the manufacture of supercapacitor electrode materials. Potassium nitrate was selected as an activator instead of a strong corrosive activator. The prepared porous carbon material has a high specific surface area (2400 m2/g). Potassium benzoate is weakly alkaline and corrosive. As an activator, it can generate a large number of microporous structures and introduce potassium atom doping, Lu et al. [82] selected it, used plum shells as carbon precursors, and N, N'-diphenyl thiourea as nitrogen and sulfur sources to prepare nitrogen–sulfur co-doped porous carbon by one-step method. Doping nitrogen atoms can improve the wettability of carbon, and the introduction of larger sulfur atoms will lead to more polarized surfaces and defect structures, ensuring a larger specific surface area. The introduction of heteroatoms provides more active sites for reversible redox reactions. At the same time, N, N'-diphenyl thiourea also played a synergistic activation role in the preparation process. The decomposition of N, N'-diphenyl thiourea produced some volatile gases and nitrogen and sulfur substances. The emission of volatile gases further promoted the formation of pores. The prepared porous carbon material has excellent wettability, and the specific capacitance is 338 F/g at a current density of 0.5 A/g in 6 mol/L KOH electrolyte. The rate performance is excellent, and the retention rate is 92.3% after 10, 000 cycles. As we all know, straw (such as corn, wheat, rice) is widely used in rural areas for cooking, producing hundreds of tons of plant ash every day, often discarded. Considering that plant ash is rich in K+, Ca2+, Mg2+ in the form of oxides or carbonates, Yin et al. [83] developed a simple direct heat treatment to prepare porous carbon with seeds as carbon precursor, plant ash as activator, and eggshell (83%–85% calcium carbonate) as hard template. The activation process includes the decomposition of K2CO3, the reaction with C and the decomposition of CaCO3. The obtained carbon specific surface area with a high yield of 75% is 343.6 m2/g, the specific capacitance at 0.5 A/g is 250.5 F/g, and good cycle stability (10, 000 cycles, the capacitance retention rate is about 99.0%).

The activated carbon prepared by the mixed activator has more mesopores, macropores and specific surface area than the single activator, and introduces heteroatom doping to a greater extent. The modification of biomass-derived porous biochar by heteroatom doping can significantly improve the capacitance performance. Yuan et al. [84] used corn straw as raw material, K2CO3 as activator, melamine as nitrogen source, phytic acid as phosphorus source and activator at the same time, etch carbon materials to generate more mesopores and micropores. N and P elements were uniformly doped in the carbon skeleton. The specific surface area of the prepared sample was 1136.31 cm2/g, and the specific capacitance was 203.5 F/g at 1 A/g current density. After 5000 cycles at 10 A/g current density, the capacitance did not decrease and the cycle stability was good. Kong et al. [85] used laver as precursor and KCl/ZnCl2 as composite activator and porogen to prepare carbon materials with high specific surface area (1514.3 m2/g), three-dimensional interconnected hierarchical porous structure and abundant heteroatom doping. Ning et al. [86] prepared porous carbon materials by one-step carbonization reaction using succulent leaves as raw materials, Mg(NO3)2·6H2O and zinc chloride as dual activators. The porous carbon material has superior specific surface area (2136.2 m2/g) and excellent electrochemical performance (specific capacitance of 455.3 F/g at 1 A/g). Using waste tea as raw material, ZnCl2 and Mg5(OH)2(CO3)4 as dual activators, Zhang et al. [87] prepared samples with large specific surface area (1968.6 m2/g) and specific capacitance (321 F/g at 1 A/g). Zhao et al. [88] prepared N, P and S co-doped porous carbon materials by one-step simultaneous carbonization and activation using peanut powder as raw material, ZnCl2 and Mg(NO3)2·6H2O as dual activators. The specific surface area is 2090 m2/g, and the total pore volume is 1.42 cm3/g. Mg salt and ZnCl2 are transformed into metal oxides (MgO and ZnO) under anaerobic high temperature conditions, which are used as double templates. The possible reaction principle is as follows: With the increase of temperature, zinc chloride gradually transforms into zinc oxide as a template, and pores are formed after etching in hydrochloric acid solution. When the temperature rises to 600 ℃, as the carbon begins to form, some zinc oxide is further transformed into metal zinc, which is released in the form of steam to generate pores in the carbon skeleton. Mg5(OH)2(CO3)4 is completely transformed into magnesium oxide in the carbon framework. After etching treatment, pores will also be generated. The materials prepared by co-activation are dominated by micropores and rich in mesoporous macroporous structures.

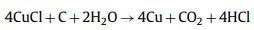

However, the traditional heating device has the problems of uneven heating, long time required and high cost. The emergence of new heating methods solves this series of problems well [89]. Microwave pyrolysis produces a large amount of heat through the electromagnetic oscillation and high-speed movement of molecules [90]. As a novel biomass pretreatment method, it is more energy-saving and efficient. Single microwave-assisted hydrothermal carbonization is not enough to form porous carbon with excellent electrochemical properties. It is usually necessary to further chemically activate with activators and then hydrothermally treat to obtain porous carbon with layered pore structure. Bo et al. [91] used biomass waste of camellia oleifera as raw materials. After pre-carbonization at 400 ℃, potassium hydroxide was added as an activator and microwave treatment was performed. The carbonized material can absorb microwave radiation and heat up sharply within 2 min. The prepared porous carbon material has a rich pore structure and a large surface area of 1726 m2/g. Beet pulp is rich in cellulose structure and rich in yield. Emre Gür et al. [92] used beet pulp as raw material, citric acid as catalyst, and microwave-assisted hydrothermal treatment at 200 ℃ to explore the activation effect of Mg (CH3COO)2·4H2O and ZnCl2 as activators at 500, 600 and 700 ℃, respectively. After dehydration, Mg (CH3COO)2·4H2O is converted to magnesium oxide at high temperature. The main reactions are as follows:

|

(19) |

|

(20) |

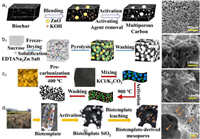

The experimental results show that the sample prepared by using ZnCl2 as the activator has a richer mesoporous structure than the sample prepared by using Mg (CH3COO)2·4H2O. The specific surface area of the prepared porous carbon is up to 950.31 m2/g. When the activation temperature is 700 ℃, the prepared electrode exhibits higher capacitance in alkaline water electrolyte. In 6 mol/L KOH electrolyte, when the current density is 0.5 A/g, the energy density is 16.3 Wh/kg. When the current density is 5 A/g, the power density is 3750.9 W/kg. In addition, the use of ultrasonic assisted is also a new process to reduce the activation temperature and achieve energy saving effect. Under the action of ultrasound, the reactants are uniformly mixed, the diffusion of reactants and products is accelerated, and the solid-liquid multi-phase reaction rate is increased. Zhou et al. [93] successfully prepared straw-based porous carbon by microwave-assisted method at 500–700 ℃ activation temperature with NaOH as activator (Fig. 6a). When the activation temperature is 600 ℃, the specific surface area is 1820.2 m2/g, showing a high specific capacitance (420 F/g at 1.0 A/g). Chen et al. [94] proposed a flame combustion carbonization strategy in air, using molten salt flame retardants to prepare biomass-based porous carbon materials. With cotton, dandelion and catkin as precursors and K2CO3–KCl molten salt as flame retardant, the carbonization time during flame combustion is only 10 min. In the process of flame combustion carbonization, biomass combustion produces carbon dioxide, water and other gases. The K2CO3–KCl and the molten salt liquid obtained by rapid melting of high temperature flame can cover the surface of biochar and prevent it from contacting with air, thus becoming a flame retardant. K2CO3–KCl also has the function of activation and template. As the temperature further increases to 800 ℃, K2CO3 begins to decompose to form KCl molten salt, and the generated CO2 and K activate carbon. During the combustion carbonization process, due to the short carbonization time, the molten salt will be dispersed into the sample, resulting in uniform pore size (Figs. 6b–d). At the same time, when the carbonization temperature is lower than the melting point of the molten salt, the salt is embedded in the carbon skeleton and can be used as a template to prepare three-dimensional layered porous carbon.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a) Preparation process and burning mechanism of FBCT-X and TF-X, and the corresponding processes can be indicated. SEM images of (b) FBC10-Cot, (c) FBC10-Dan, and (d) FBC10-Cat. Reproduced with permission [94]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. | |

Chemical activation is widely used due to its lower operating temperature, easier operating procedures and adjustable porosity. The activation process requires quantities of chemical substances, and washing after activation also requires a large amount of acid solution, alkali solution and water, and chemical activation is not conducive to the formation of graphite carbon, which limits the conductivity of carbon materials to a certain extent. And chemical activation may introduce excessive functional groups, which reduce electronic conductivity and may be harmful to rate performance and stability. In some cases, chemical activation may lead to uncontrollable pore size distribution [23].

3. Unconventional activationHowever, the control of pore size by traditional activation methods is limited, which seriously limits the further development of carbon materials. In order to meet the need for renewable and cheap energy materials, the activation of biomass porous carbon requires some alternative strategies.

3.1. Self-activation methodStudies have shown that some biomass rich in cellulose and potassium and sodium can be directly converted into porous carbon with high specific surface area, without the need for additional activators. gases emitted from water, carbon dioxide or H2 to the carbon skeleton led to the formation of pores. Chrysanthemum is rich in cellulose and has high potassium and sodium content [95,96]. Zhang et al. [97] selected Glebionis coronaria as raw material. Since cellulose and lignin are the main components of xylem vessel cells, lignin is converted into a carbon framework at high temperature, which avoids the complete collapse of the xylem container after carbonization. Cellulose reacts with gases released during pyrolysis/carbonization, such as water, carbon dioxide and H2, to produce developed porosity. Because the specific surface area of the prepared porous carbon material is 1007 m2/g, the obtained activated carbon has a high bulk density and rich pseudocapacitive sites. Symmetric supercapacitors have high volumetric specific capacitance and energy density (the maximum values are 264 F/cm3 and 23.5 Wh/L, respectively). Yang et al. [98] selected wild hollyhock as raw materials. After carbonization, the porous tubular transport tissue was still retained, forming a large number of interconnected macroporous and mesoporous porous carbon skeletons. At the same time, due to its high cellulose content, it is self-activated during the carbonization process to form a rich microporous structure, and the prepared material has a high specific surface area (954 m2/g).

During the carbonization process, the reaction of the carbon skeleton itself will release a large amount of small molecule gases, such as CO2 and H2O. Du et al. [99] developed a closed pyrolysis method to construct a compact silicon shell closed structure. The resin is used as the precursor to fabricate a hollow carbon sphere with a rich porous structure. The closed and dense silicon shell structure effectively prevents the escape of gas. Using the gas released by the reaction itself as an activator, the prepared porous carbon material exhibits excellent specific capacitance (330 F/g at 0.5 A/g). After 10, 000 cycles, the stability is excellent. The initial capacity retention is 88.5%. On this basis, Du et al. [100] continued to study the silicon-limited activation method, using microcrystalline cellulose as a carbon precursor, tightly wrapped with a silicon coating, and pyrolyzed in an inert atmosphere. The gas generated by the reaction preferentially stays in the closed pores of the MCC, rather than being released into the atmosphere under the obstruction of the closed space of the dense silica layer, in which CO2 and H2O activate the carbon skeleton to form a rich mesoporous structure. The specific surface area of the prepared sample can reach 797 m2/g, which is 33% higher than that of the limited activation method without silicon coating.

3.2. Bioactivation methodDue to the rich sugar content of biomass itself, the introduction of yeast is considered to develop a green and inexpensive activation process. By introducing yeast, yeast respiratory conversion produces alcohol and releases carbon dioxide to form pore structure. Lian et al. [101] used banana peel as raw material, mixed active dry yeast with warm water to activate yeast, pressed banana peel into small pieces and mixed the two materials evenly. The samples were stored in a water bath at 37 ℃ for 3 h and then carbonized at 900 ℃ for 1 h in N2 atmosphere. The prepared sample has a rich pore structure due to yeast respiration, which is dominated by microporous structure. The total specific surface area is 1084 m2/g, and the micropore specific surface area is 706 m2/g.

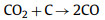

3.3. Template assisted activation methodConventional physical and chemical activation methods can be used to develop large specific surface area and pore volume, but it is difficult to obtain ordered nanoporous structure. The template carbonization activation strategy can effectively control the morphology and pore size, and can be used to develop pore size and balanced ordered microstructure in the range of 1–200 nm [102]. The template carbonization activation strategy can be divided into two steps. The first is the carbonization of carbon precursors and hard template composites [24]. The hard template includes zeolite, SiO2, nano-CaCO3, etc., and the mesoporous structure is generated by carbonization. The second step is the activation of chemicals such as KOH and NaOH to form microporous structures. Li et al. [103] selected boric acid as a new activator, using auricularia as raw material, through soaking, the volume of dried auricularia will expand to 3.5 times the original size, under the action of hygroscopicity, boric acid can enter the interior of auricularia well. During the carbonization process, boric acid first melts into molten Be2O3, which has high viscosity and excellent wettability, adheres to the agaric matrix, and then KOH is used to remove the Be2O3 template. The prepared material has a typical honeycomb-like porous structure. It contains a large number of mesoporous structures, and the specific surface area of the prepared material can reach 2279.5 cm2/g. Chun-Hsiang Hsu et al. [104] used rhombus shells as raw materials, nano-zinc oxide as a template, and KOH as an activator to prepare porous carbon materials with a specific surface area of up to 1537 m2/g and good electrochemical performance (128 F/g at 5 mV/s). However, nano-zinc oxide can not only be used as a template for the production of mesopores, but also as an activator for the preparation of layered porous carbon (Figs. 7a1 and a2). Wang et al. [105] selected EDTANa2Zn salt as a hard template, activator and nitrogen source at the same time. Sucrose was used as a carbon precursor and EDTANa2Zn salt was mixed in deionized water. After freeze-drying and curing treatment, a composite material with intertwining structure was obtained. EDTANa2Zn salt was decomposed to produce zinc oxide and Na2CO3 nanoparticles. Na2CO3 nanoparticles were used as hard templates. As the carbonization temperature increased, nano-ZnO was used as an activator. It reacts with the carbon material to etch to form a microporous structure. Zn exists in the form of simple substance until 907 ℃ reaches the boiling point of Zn, leaving small mesopores by evaporation (Fig. 7b1). After washing with hydrochloric acid to remove the template, a nitrogen-doped carbon with a layered porous structure was obtained (Fig. 7b2). The prepared porous carbon material has the highest specific capacitance of 283 F/g at 0.1 A/g. In addition, it has high specific surface area (2160 m2/g) and high nitrogen content (1.85%), and has excellent rate performance and cycle durability. Jiang et al. [106] used waste straw as raw material and nano-zinc oxide as both template and activator. Nano-zinc oxide has a placeholder effect to produce rich mesoporous structure, and etched carbon atoms at high temperature to form microporous structure. The optimum carbonization temperature was explored through experiments: when the carbonization temperature was 800 ℃, the specific surface area of biochar was the highest, reaching 1293.2 m2/g. Molten metal salts are also often used as templates. Salt templates have lower eutectic points, which can increase the contact area between carbon precursor and activator at low activation temperature, thus greatly improving the utilization efficiency of activator. As an excellent thermochemical medium, it has strong thermal conductivity. The molten salt medium has good reaction ability with impurities (such as silica [107] and potassium oxide [108]) in biomass, and high purity derived carbon is obtained. As a green nontoxic template, chloride can adjust the pore structure and microstructure of carbon materials. Zhang et al. [109] prepared porous carbon nanosheets derived from Ginkgo biloba leaves using CaCl2 and KCl molten salts as activators and templates. Calcium chloride has a dual role in the preparation of porous carbon materials. First, the fixed ammonia comes from the decomposition of the ammonia precursor, resulting in high nitrogen content in the synthesized carbon product, on the other hand, calcium chloride can be used as a pore-forming / expansion agent to introduce pores into carbon matrix materials during carbonization, resulting in the formation of pores in the final carbon products. At the same time, potassium chloride can also be used as a template to penetrate into the carbon precursor to form pores. Adjusting the ratio of molten salt is the key to the preparation of porous carbon materials with high porosity. With the increase of KCl ratio, the specific surface area of the prepared carbon materials increases. When the molar ratio of KCl and CaCl2 is 0.75:0.25, the prepared carbon-based supercapacitor exhibits a good specific capacitance of 150.4 F/g at 0.05 A/g. After 10, 000 charge and discharge cycles at 1 A/g, it has good cycle performance, capacity retention of 94.2%, and electrochemical performance is the best. On this basis, Zhang et al. [110] further prepared N/S co-doped flake porous carbon from Ginkgo biloba leaves by using molten salt KCl/K2CO3 as template and activator (Fig. 7c1). The main activation effect is chemical/physical activation and carbon lattice expansion caused by K2CO3.When KCl is used as a template, Cl-etching carbon skeleton will also form a pore structure (Fig. 7c2). The prepared porous carbon material as an electrode has 215.2 F/g at 0.05 A/g and maintains 78.9% at 20 A/g (169.8 F/g at 20 A/g). There is only 1.6% capacity decay after 10, 000 charge and discharge cycles. However, although the biomass porous carbon materials produced by template carbonization activation have large surface area and mesoporous structure, most of them are dominated by micropore effect. Although they have high capacitance, their rate performance is poor. Therefore, Hu et al. [111] proposed a preparation strategy based on the combination of in-situ hard template method and NaOH activation. The lotus seed shell was used as the carbon precursor and sodium phytate was used as the hard template precursor, which was fully mixed to form a mixed gel. Soluble sodium phytate was pyrolyzed to nano-Na5P3O10 during carbonization, and then reacted with NaOH to form nano-Na2CO3 and nano-Na3PO4 particles, which were uniformly dispersed in the carbon matrix and left mesopores after washing. Combined with the micropores generated by sodium hydroxide activation, a well-developed layered porous carbon with a hollow nest structure was obtained, with a high specific surface area (3188 m2/g) and a large pore volume (3.20 cm3/g). Although the prepared porous carbon material has good performance, the preparation process involves the preparation of nano-templates and the complex steps of dispersing in carbon precursors. For rough biomass, the growth structure is compact, the nano-templates cannot penetrate well, and the hard template method is not applicable. Chen et al. [112] have noticed that some biomass raw materials contain a large amount of minerals, such as calcium and silicon, which can be used as an internal biological template for in-situ mesoporous development. Not only does it not need to introduce additional template substances, but also the biological template is well distributed in the biomass and does not require laborious mixing and dispersion. On this basis, a preparation method combining self-template method and chemical activation was proposed. Rice straw containing a large amount of dispersed silicon (10%–20%) was selected as the raw material, and uniformly dispersed SiO2 was used as the biological template. When the activator KOH/K2CO3 reacts with organic matter at high temperature, the loss of C, H and O leads to the opening of pores. At the same time, SiO2 particles aggregate into larger particles. The diameter range of these larger silica particles is very wide (Fig. 7d1). Removal of these particles will lead to abundant nanopores, and activation will generate a large number of microporous structures (Fig. 7d2). The porosity of the prepared samples is reasonable. It allows rapid transport of ions with a large specific surface area and additional pseudocapacitive behavior. As a result, the prepared material has excellent capacitance retention and excellent cycle stability for 357 F/g (0.5 A/g, 1 mol/L H2SO4) of the three-electrode system and 260 F/g (1 A/g, 1 mol/L sodium sulfate) of the two-electrode system, which is superior to most biomass-derived carbon. In addition, the energy density is as high as 29.3 Wh/kg at a power density of 900 W/kg.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. (a1) Scheme of the formation mechanism of the mesopore and micropore in the WCS biochar by using ZnO nanoparticles and KOH as activating agents. (a2) SEM images of the WCS biochar. Reproduced with permission [104]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (b1) Schematic diagram for the preparation of nitrogen-doped hierarchical porous carbons. (b2) SEM images of ESCT samples. Reproduced with permission [105]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (c1) Schematic illustration for the synthesis process of KISPCs. (c2) FESEM images of KISPC. Reproduced with permission [110]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (d1) Scheme of preparing N-self-doped HPC from RS via the self-biotemplating method. (d2) SEM images of DAC-KHCO3. Reproduced with permission [112]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society. | |

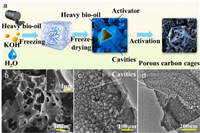

Although the materials prepared by carbonization and activation have rich pore structures, due to the structural shrinkage caused by the entanglement of natural macromolecules during carbonization, biomass-derived carbon tends to form blocked carbon bodies rather than cavities. The internal space is shielded by the shell, which makes the surface area of ion storage difficult to access and ion transport slow. Opening the internal carbon space is the key to improve the electrochemical performance of biomass-derived carbon. Xue et al. [113] prepared porous carbon cages with heavy bio-oil by ice template-assisted activation method (Fig. 8a). The ice crystal is used as a template to grow. By adjusting the volume of the ice crystal, a suitable cavity is formed to prevent the shrinkage of the carbon framework, and the activator is transported to the carbon block to obtain a high accessible surface area (Figs. 8b–d). The obtained porous carbon has an open junction with a cavity and a layered shell.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. (a) Schematic illustration of ice template-assisting activation for porous carbon cages. (b) SEM image of PCC-3 (inset: magnified observation). (c, d) TEM images of PCC-3. Reproduced with permission [113]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. | |

Although carbonization activation has been successfully used to fabricate porous carbon with mesopores, micropores or layered pores, and these porous carbon electrodes have greatly improved the electrochemical performance of supercapacitors. However, relatively low energy density and rate performance still greatly limit its practical application in the future [114,115]. Balancing the appropriate mesoporous volume and high specific surface area is a major challenge today. Wang et al. [116] carried out pre-carbonization and KOH continuous activation of wheat husk by chloride salt sealing technology. In the carbonization process, a mixture of potassium chloride and sodium chloride was used as a salt template to form mesopores in the carbon framework. At the same time, the mixed salt can be used as a shielding agent to prevent the carbon framework from oxidizing in the air at high temperatures. The mesopores in the carbon framework can provide active sites for the continuous activation of potassium hydroxide to produce a large number of micropores. Due to the synergistic pore-forming effect of molten salt and potassium hydroxide, the obtained porous carbon exhibits a layered pore structure with a good balance between high specific surface area and mesoporous volume. In a three-electrode system, biomass-derived porous carbon exhibits a high specific weight capacitance of 402 F/g at 1.0 A/g. In a two-electrode symmetric supercapacitor, the biomass-derived porous carbon also provides an excellent specific weight capacitance of 346 F/g at 1.0 A/g, and a good cycle stability of 98.59% after 30, 000 cycles at 5.0 A/g.

3.4. Green activator activationChemical activation is increasingly challenging due to its associated high corrosivity and toxicity. In addition to these shortcomings, the chemical activation method has a low manufacturing yield, which limits the amplification ability of industrial applications [117]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to adopt greener synthesis strategies based on harmless, non-corrosive activated chemical reagents and sustainable, cost-effective carbon precursors such as biomass-based products and sub-products.

Yan et al. [118] found that low-temperature hydrothermal activation is simpler and more energy-saving, in which the wet chemical activation method can introduce abundant heteroatom functional groups while etching the carbon framework. However, the wet chemical activators currently used are mainly corrosive acids (e.g., nitric acid and sulfuric acid) [119]. Therefore, the development of more environmentally friendly wet chemical activators is crucial for customizing the capacitance performance of thick carbon electrodes with high-quality loads. As the substrate of wood-based electrodes, carbonized wood has a unique three-dimensional layered porous structure [120]. Electrons are continuously transmitted through the cell wall, and ions are transmitted along the nanopores in the wood channel. A green, versatile and versatile H2O2 hydrothermal activation strategy was reported to prepare linden-derived thick carbon electrodes with ultra-high mass loading (40 mg/cm2) and excellent capacitance performance (Fig. 9a). The H2O2 activation method involves etching and oxidation processes. On the one hand, H2O2 molecules begin to etch from the relatively active oxygen-containing carbon atoms and gradually diffuse to the entire carbon base surface, expanding the original nanopores in the carbon skeleton or forming new nanopores, thereby improving the electric double layer capacitance performance of the electrode [121]. On the other hand, the H2O2 oxidation process introduces abundant oxygen-containing species to the carbon skeleton, which improves the wettability of the electrode and contributes additional pseudocapacitance. As shown in Figs. 9b–d, the appearance of more nanopores confirms the pore-forming effect of hydrogen peroxide activation. The capacitance performance of the high-load electrode in alkaline (6 mol/L KOH), acidic (1 mol/L H2SO4), and neutral (1 mol/L Na2SO4) electrolytes was investigated. The electrode has the best performance in 6 mol/L KOH. When the current density is 5 mA/cm2, the specific capacitance reaches 6205.7 mF/cm2 (77.6 F/cm3, 221.6 F/g). When the current density increases to 100 mA/cm2, the specific capacitance can still maintain 78% of the initial specific capacitance. It can still exhibit excellent capacitance performance under extreme conditions (−40 ℃) (Figs. 9e–g). With the rapid development of advanced energy storage devices, not only under normal conditions, but also under extreme conditions, the scope of use is becoming more and more extensive, which brings new challenges to the energy field [122]. Wang et al. [123] obtained an ultra-low temperature and high capacity solid-state ZAB|SSE interface without organic solvent by combining the Mn atom cathode with the Zn atom. The prepared water-based ZAB not only provides impressive rate performance and ultra-long discharge life, but also shows good stability in extremely harsh environments. It not only highlights the importance of atomic structure design of oxygen electrocatalysts for ultra-low temperature and large capacity ZABs, but also promotes the development of sustainable energy storage devices under harsh conditions. The (Fe, Co)Se2@Fe1/NC composite electrocatalyst prepared by Zheng et al. [124] accelerates interfacial electron transfer and reduces energy barriers, showing excellent bifunctional properties. The assembled SS ZABs have high peak power density and good cycle performance at high current density. It also has a certain degree of reliability for mechanical damage (cutting and nail penetration), suggesting its great potential for high safety energy storage under harsh conditions.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis process of a-OC materials. HRTEM images of (b, c) OC-900 and (d) a-OC-900, (e) Rate performance and (f) EIS plots of the assembled devices at different temperatures. (g) Long cycling stability of the assembled device over 70, 000 cycles under 30 mA/cm2 at −40 ℃. Reproduced with permission [118]. Copyright 2022, Royal Society of Chemistry. (h) Illustration of the synthesis procedure: (A) Blend of the raw materials (sawdust, KCl and Na2S2O3). (B) Mixture of the pyrolyzed sawdust with KCl and Na2SO4. (C) Porous carbon–KCl–Na2S monolith. (D) Porous carbon. SEM micrographs of the carbon materials produced from sawdust (i, j) and tannic acid (k, l). Reproduced with permission [126]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. The surface micrographs of W800–3: (m) 1.5k magnification, (n) 10k magnification, (o) 50k magnifications. Reproduced with permission [127]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier. (p) Morphological evolution process of KMnO4@hemp stem during KMnO4 one-step activation. SEM images of (q, r) the hemp stem and (s) MHPC-1.75 (unwashed). Reproduced with permission [128]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. | |

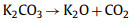

Sevilla et al. [125] reported a new environmentally friendly synthesis strategy (Fig. 9h), which uses Na2S2O3 as an activator and inert salt (KCl) as a suitable reaction medium to produce highly porous carbon based on various biomass products (such as gelatin, sucrose and glucose). The activation process provides a green and sustainable measurement rate for the production of porous carbon, as only affordable and environmentally friendly ingredients are used. The activation process is basically based on the high-temperature redox reaction between carbon-containing substances and sodium sulfate produced by the decomposition of sodium thiosulfate:

|

(21) |

|

(22) |