Energy and environmental crises have considerably increased due to rapid societal and industrial development. The consumption of fossil energies, such as oil and coal, has led to the development of renewable energy sources, including ocean energy, solar power, geothermal energy, and wind power [1–3]. A secondary battery is a promising energy storage equipment for storing and improving the utilization rate of renewable energy sources and reducing the power supply demand during peak hours. Additionally, it is characterized by high energy density, pollution-free, lightweight, and long service life [4–7]. At present, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are extensively used in household appliances and electric vehicles owing to their advantages of long lifespan and energy density [8]. The rapid market growth of electric vehicles, mobile electronics, power grid energy storage, and other devices has promoted the vast development of commercial LIBs, and the market size of LIBs is expected to be $99.98 billion in 2025 [9,10]. Nevertheless, problems of limited Li resources, high production costs, and safety hinder large-scale applications of LIBs [11–16]. Therefore, developing cheaper and safer alternatives to LIBs with comparable energy density is crucial.

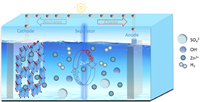

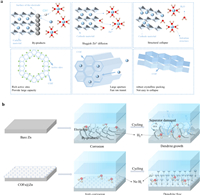

Zinc-ion batteries (ZIBs) are considered one of the most excellent alternatives to LIBs owing to the favorable characteristics of their anode materials (including low cost, high natural abundance, and environment-friendly characteristics) and water-based electrolytes (including flame retardant, nontoxic, and high ionic conductivity) [17–25]. In addition, the frequent safety accidents in practical applications of LIBs are also warning us that developing a safe and efficient battery is imperative. In contrast, high security is a major advantage of ZIBs. Especially in areas with high safety requirements such as home energy storage, electronic wearable devices, and oil fields and mines, ZIBs must be a potential candidate. And a large number of researchers have made efforts to achieve this. For example, Li et al. developed a water-based zinc battery with softness and safety as its selling points, providing an important reference for its application in the field of wearable electronic products [26]. In addition, the high safety requirements of two-wheel electric vehicles but slightly lower energy density requirements compared with electric vehicles provide greater development space for ZIBs. From this, it can be boldly speculated that the practical application of ZIBs in the future may begin with two-wheel electric vehicles. The structure of ZIBs is similar to that of LIBs, and both batteries comprise a cathode, an electrolyte, a diaphragm, and an anode. A cathode material with high capacity and rate capability and a Zn metal anode with high energy density and low potential (−0.762 V compared with a standard hydrogen electrode) are used to assemble the battery [27–29]. ZIBs are also a type of "rocking chair battery" [30,31]. In most ZIBs, the Zn deposition/dissolution reaction occurs on the Zn anode surface, and the Zn2+ embedding/removal reaction occurs in the cathode material [32,33]. During the discharge procedure, the Zn metal is oxidized into Zn2+ and dissolved into the electrolyte. Then, the Zn2+ ions flow into the cathode layer or tunnel structure, and the electrons flow in the outer circuit to produce a current. During charging, Zn2+ is removed from the cathode and deposited on the surface of anode (Fig. 1) [34–37]. In past few years, numerous studies have been conducted to improve the properties of ZIBs. However, the production of ZIBs is still limited to the laboratory scale, which is far from commercialization, because (1) the dissolution of the organic cathode during the battery cycle shortens the service life of the battery, and the slow insertion/removal of Zn2+ in the cathode reduces the ion cycle rate, thus affecting the battery cycle performance [38–44] (2) the spontaneous side reaction (hydrogen evolution reaction, HER) and uneven sedimentation and dissolution process lead to the formation of deadly Zn dendrites, which significantly shortens the battery life and creates safety problems (Fig. 2) [45–50]. Therefore, to solve these problems, the exploration of novel cathode and anode materials for ZIBs is vital.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Working schematic diagram of ZIBs. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Limitations of traditional cathode and advantages of using COF as a cathode. (b) The comparison of bare Zn and COFs@Zn anodes for ZIBs after cycling. | |

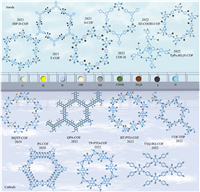

At present, different porous materials, such as covalent organic frameworks (COFs), porous organic polymers (POPs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have received widespread attention owing to their porous structures (which facilitate electrolyte penetration and ion transport) and their adjustable chemical properties and structures [5,51–53]. COFs are crystalline organic porous materials mainly comprising C, N, O, and B, which are linked by strong covalent bonds [54–58]. Fig. 3 shows the combination of constructional elements with different geometric shapes forming COFs and common dynamic chemical reactions for preparing COFs. Compared with MOFs, COFs are composed of light elements with higher energy density. COFs exhibit high stability in multifarious solvents; however, the constancy of MOFs remains challenging [5,59,60]. Compared with amorphous POPs, COFs have more ordered pores, which are more conducive to ion transport [61,62]. In addition, using COFs in batteries can accelerate ion conduction, promote uniform ion deposition, and inhibit the growth of dendrites [4,63,64]. Moreover, COFs can supply a stable chemical and physical reaction environment owing to the highly crystalline π-π conjugated structure, thus facilitating the stable operation of the battery under different cathode and anode polarization conditions [65–67]. Thus, COFs play a pivotal role in LIBs, Na-ion batteries, and potassium-ion batteries. To solve the current challenges facing ZIBs, many researchers have applied COFs to improve the performance of ZIBs. The multiple active sites, large pore channels, and rigid structure of COFs can eliminate the problems associated with traditional cathodes, such as low capacity, slow Zn2+ diffusion, and structural collapse. The uniform pore and plentiful active sites in COFs ameliorate the uniform deposition of Zn2+ on the anode surface, thereby inhibiting the formation of dendrites and alleviating the corrosion, passivation, and HER on the anode surface (Fig. 2) [5]. For instance, Wang et al. synthesized a COF containing quinones through solvothermal condensation reaction, denoted as HAQ-COF. Experimental and theoretical calculations showed that HAQ-COF (the cathode of ZIBs) had high coulomb efficiency (CE) and stable cycling performance under high current density [68]. Wu et al. designed a 3D-COOH—COF membrane with affluent functional groups and regular nanoscale channels, which was synthesized in situ as a protective film for stable Zn anodes. Results showed that the 3D-COOH—COF film improved the cycle times of Zn| |Zn symmetric batteries and the CE of the full batteries [69]. In last few years, numerous studies have adopted COFs to handle the cathode and anode problems of ZIBs (Fig. 4). However, to our knowledge, there are few systematic and comprehensive reviews on COFs for ZIBs. Therefore, in this essay, we introduce and discuss the synthesis methods and characterization techniques of COFs and the current advances of COFs for ZIBs. Finally, the current challenges and future prospects are discussed.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) The combination of building blocks with different geometries to form COFs. (b) Common dynamic chemical reactions for preparing COFs. | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Development of COFs applied in zinc-ion batteries. | |

COFs were first reported by Yaghi et al. in 2005, and COFs have attracted considerable scholarly attention [70,71]. At present, COFs are extensively used in photocatalysis, gas storage and separation, energy storage, and energy conversion [72–76]. Studies have reported various synthesis methods for COFs. The methods include solvothermal, microwave-assisted, ionic thermal, mechanochemical, and interfacial synthesis methods (Fig. 5) [4,77–79]. This section briefly describes the characteristics of different synthesis methods.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Different synthesis methods of COFs. | |

Among all synthesis methods, the great majority of COFs are synthesized through solvothermal methods. Solvothermal synthesis of COFs demands heating in an inert gas ambiance. The reaction time and temperature significantly affect the crystallization and porosity of COFs. The reaction time of synthesizing COFs using this method is 1–9 d, and the reaction process is generally performed at 80–200 ℃ [80,81]. In addition, the pressure in the sealed container significantly affects the reaction. Yaghi et al. found that the best pressure in a vacuum tube before the container was sealed at a given capacity (about 10 cm3) was 150 mTorr [70]. Moreover, the choice of solvent plays a critical role in the formation of COFs, which strongly affects the solubility of the reactants. COFs are usually prepared by mixing two or more solvents. The proportion of solvents also affects the COFs crystallinity [79,82]. For instance, Jiang et al. prepared Porphyrin-based COF using a solvothermal method. With the solvent ratio of 1:1 (v: v) between mesitylene and dioxane, the amorphous solid product was formed, as determined using powder X-ray diffraction. With the solvent ratio of 9:1 (v: v) between mesitylene and dioxane, high crystallinity COFs were formed [83]. The solvothermal method is usually used to produce COFs as a powder, which may restrain its application in some cases, for example, for the interfaced integration into devices.

2.2. Microwave-assisted methodBecause the solvothermal method usually takes a long time to prepare COFs, the microwave-assisted method was explored to prepare crystalline porous COFs [78]. Microwave heating synthesis is simpler, faster, and more efficient than solvothermal synthesis and can achieve uniform stirring at the molecular level [79,84]. In 2015, Wei et al. synthesized the Schiff base TpPa-COF through the microwave-assisted method. The solvothermal method requires 2–3 d to complete the reaction, while the microwave heating synthesis method only requires 60 min to complete the reaction, indicating that the microwave heating method can effectively synthesize the TpPa-COF with high crystallization and stability in a short time [85]. In addition, COF-5 synthesized through the microwave-assisted method had a higher BET area (2019 m2/g) than that synthesized through the solvothermal method in a sealed container (1590 m2/g) [86]. However, the microwave heating method does not apply to all COF materials compared with solvothermal synthesis. Therefore, this method has great limitations and is rarely used to study multipore COFs.

2.3. Ionic thermal methodCOFs synthesized through ionic thermal method was first reported in 2008 by Thomas et al. [87]. Under high-temperature conditions, COF materials are synthesized using eutectic mixture or ionic liquid as a medium [88]. To date, ionic thermal synthesis of COFs has only been used to synthesize triazine COF materials [4]. In molten ZnCl2, covalent triazine-based frames (CTFs) can be provided through the cyclic trimerization of nitrile constructional units (e.g., 1,4-dicyanobenzene) at 400 ℃ with excellent crystallinity and ideal stability. Fused ZnCl2 salts play a vital role in synthesizing CTF, serving as solvents and catalysts for reversible cyclic trimerization. Compared with solvothermal synthesis and microwave synthesis, ionic thermal synthesis requires extremely harsh reaction conditions for the synthesis of high crystallinity COFs. Additionally, ionic thermal synthesis requires an extremely high temperature to melt the metal salt as the solvent and requires the monomer of the synthesized COF material to have good thermal stability [77]. These requirements limit the application of ionic thermal synthesis for synthesizing multipore COFs.

2.4. Mechanochemical synthesis methodThe mechanochemical synthesis method is a simple, economical, and environmentally friendly process at room temperature [89]. In 2013, Bhaierjee et al. synthesized high-stability two-dimensional COF materials, including TpBD (MC) and TpPa (MC), through mechanical grinding at indoor temperature without solvent [90]. Compared with solvothermal and microwave processes performed under complex conditions, such as reactions in sealed pyretic glass tubes, inert atmospheres, suitable solvents, and crystallization temperatures, the mechanochemical synthesis method is considered an environmentally friendly, and it is a more suitable synthesis method for mass production [4]. However, the mechanochemical synthesis method is rarely used to synthesize COFs due to the general crystallinity and specific surface area of the synthetic materials [78,79].

2.5. Interface synthesis methodThe COFs obtained through the above methods are usually insoluble and laborious to produce microcrystalline powders, significantly limiting the wide range of application of COF materials. Compared with the methods above, the interfacial synthesis method is extensively applied for preparing COF films [91–93]. In this approach, COF are restrictedly grown at the interface through the reaction among the monomers, finally forming COF films [78,79,94]. Recently, various interface synthesis methods have been reported by researchers, including liquid-liquid, gas-liquid, solid-liquid, and gas-solid methods, for preparing COF materials, which are mainly used to prepare COF film materials that are easy to be processed and formed [95–97]. This method also provides a reference method for the processing and molding of multi-hole COF materials.

2.6. Synthesis of COFs in a novel reaction mediumTraditional COFs synthesis methods require a large amount of organic solvents, high energy consumption, and strict requirements for reaction time and temperature. In order to achieve the goal of green, environmentally friendly, efficient, and large-scale synthesis of COFs, researchers have actively explored various new synthesis strategies, such as aqueous phase mediated synthesis, ionic liquids (ILs) mediated synthesis, deep eutectic solvents (DESs) mediated synthesis [98]. These methods all use green solvents as the medium for synthesizing COFs, but they also have many differences. For example, the aqueous phase mediated synthesis method uses water and other solvents or gasses as the reaction medium for COFs [99]. This method not only has the characteristics of green, environmental protection, and low cost, but also can easily achieve the synthesis of high crystallinity COF. MartínIllán et al. synthesized imino based TAPB-BTCA-COF with high crystallinity and porosity in water using 1, 3, 5-benzenetrialdehyde (BTCA) and 1, 3, 5-tris-(4-aminophenyl) benzene (TAPB) [100]. However, the solubility of most monomers in water is poor, which is very unfavorable for the preparation of COFs. Therefore, the universality of aqueous phase mediated synthesis methods needs to be improved. The ionic liquid mediated synthesis method was first reported in 1914 [101]. ILs are usually organic ionic liquids composed of anions and cations, with characteristics such as non-volatility, good stability, high viscosity, strong solubility, and designability. Therefore, they are considered a safe and environmentally friendly chemical reaction medium [102]. In addition, ILs can not only serve as a reaction medium but also as a catalyst in the reaction, playing a dual role. As a result, the synthesis of COFs using ILs has received widespread attention. However, high viscosity ILs may hinder the reaction and lead to the formation of amorphous structures, which is currently a major obstacle to the synthesis of COFs in ILs. DESs are a new type of liquid water or analogues, considered as another new type of environmental-friendly liquid material with the exception of traditional liquid water. Compared with other methods, the COFs obtained using this method have outstanding advantages. For example, Wang et al. used this method to synthesize multiple 2D/3D COFs, which shortened the synthesis time from 72 h using traditional methods to 2 h [103]. Their porosity and stability were also much better than those synthesized using traditional methods. In addition, without obvious damage of activity, DESs can be recycled and used as a structural instruct to synthesize novel COFs with layered pore structures, which cannot be realized by conventional solvothermal methods [104]. However, numerous advantages still cannot conceal their disadvantages, as their viscosity greatly reduces the probability of successful synthesis of COFs in such media. Moreover, this synthesis method is presently only used for certain COFs, and its universal applicability is comparatively limited. In addition to the aforementioned methods, solvent free synthesis is also one of the new synthesis methods. This method reduces the dependence on organic solvents to a certain extent and is one of the best choices as an environmentally friendly alternative to general solution synthesis methods. However, the synthesis of COFs using this method is still in its early stages and there are relatively few reports currently.

3. COF material characterization technologyWith the gradual development of in-depth research on energy storage devices, researchers urgently need to develop excellent energy storage materials to meet the needs of human beings, meaning it is crucial to conduct more in-depth and detailed investigation on the action mechanism, structural changes, and factors affecting the performance of materials [105–108]. However, some traditional characterization methods have been unable to meet all current needs; as a result, the utilization of advanced characterization techniques is necessary, such as in situ/operando characterization tools, to explore the electrochemical reaction mechanism and local structure of functional materials [109]. Taking LIBs as an example, although LIBs have been successfully commercialized, the electrochemical reactions and safety issues caused by lithium dendrites limit their further development [110]. Researchers often use a variety of characterization means and instruments to examine the formation and dissolution mechanism of lithium dendrites. However, traditional ex-situ characterization means can only test the state before and after the electrode reaction without achieving dynamic testing during the process. In situ characterization allows the direct observation of dynamic structural and chemical changes in batteries, revealing complex reactions and degradation mechanisms in lithium metal anode [111]. Compared with traditional characterization techniques, in situ, characterization technique has dynamic, real-time, and intuitive characteristics. In situ characterization methods can be used to examine real-time chemical reaction processes, substance structure, and morphology and obtain information on reaction intermediates, which help researchers to analyze reaction mechanisms, thus promoting further development of materials [112,113]. Typical in situ characterization methods include in situ infrared, Raman, and synchrotron radiation techniques (for instance, in situ synchrotron radiation X-ray diffraction (SXRD) [114,115] and X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS)). In addition, as a high-precision electron microscopy technology, scanning transmission electron microscopy STEM technology supplies an "eye of observation" for humans to comprehensively study the structure of matter on the atomic scale. Since COFs are influential energy storage materials, the combined use of advanced characterization and analysis technologies has significantly improved COF-based battery materials. This section briefly introduces some examples of in situ infrared, in situ Raman, and STEM technologies applied to COF-based material characterization.

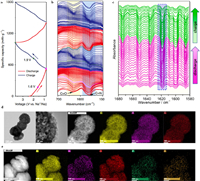

In situ Fourier infrared spectroscopy (In situ FT-IR) is an effective method of studying and characterizing molecular structures using infrared electromagnetic radiation. Moreover, the method has superiority in high accuracy, fast acquisition speed, and high sensitivity and is one of the most important scientific analytical methods for researchers [116]. Many researchers use it to characterize battery electrode materials to obtain the functional group information of electrode materials and further understanding of the electrochemical reaction process. For example, Shi et al. [117] designed a N-rich COF with triquinoxalinylene and benzoquinone units (TQBQ-COF) with carbonyl groups for a high-performance sodium-ion battery cathode by eliminating inactive linking groups and doping heteroatoms. FT-IR was used to characterize CHHO, TABQ, TQBQ-COF-200 ℃, and prepared TQBQ-COF, and the results revealed that the starting reagent was polymerized. To further analyze the structural changes of the TABQ-COF electrode during cycling, the sodiation/desodiation mechanism of the TQBQ-COF cathode in the electrochemical process was examined using in situ FT-IR. Fig. 6a shows the discharge and charge curves (at 0.02 A/g) of the first and second cycles of the TQBQ-COF cathode at the working potential of 0.8–3.7 V. As exhibited in Fig. 6b, the peaks at 1545 and 1627 cm−1 corresponded to pyrazine and carbonyl gradually weakened during discharging, consistent with the sequence combination of sodium ions and active sites of TQBQ-COF. Due to the existence of residual C=N and C=C in NanTQBQ-COF (n=1–12), the peak at 1627 cm−1 almost disappeared at 0.8 V, yet the featured peak at 1545 cm−1 remained weak. During charging, peaks of C=N and C=O reappeared, became strong, and returned to their original state. The situation in the second cycle was the same, indicating that sodiation/desodiation occurred reversibly in this electrode. Cai et al. [118] reported a triazine-based DCB-COF as an anode material for LIBs. To further explore the lithium storage mechanism, the electrode material was tested using in situ FT-IR during charge and discharge process. As visualized in Fig. 6c, an obvious tensile vibration peak assigned to the triazine in DCB-COF was observed at 1620 cm−1 in the in situ FT-IR spectrum. When the battery discharged, Li+ ions migrated into the cathode and combined with the C—N group to form a strong -C-N-Li ionic bond; consequently, the C—N bond was stronger. However, during the charging process, with the continuous removal of lithium, the bond gradually recovered to the C—N group, thus gradually weakening the C—N bond. This result suggests that inserted Li+ ions in DCB-COF can be extracted during cycling.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 6. (a) The discharge and charging curve of the TQBQ-COF electrode at a voltage of 0.02 A/g in the first two cycles within the voltage range of 0.8–3.7 V. (b) The in situ Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy spectrum collected in different states corresponding to (a). Copied with permission [117]. Copyright 2020, Nature Publishing Group. (c) The in situ FTIR spectrum of the DCB-COF-450 electrode discharged to 0.01 V (relative to Li/Li+) and then charged to 3.0 V (relative to Li/Li+) electrodes. Copied with permission [118]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. TEM and STEM-HAADF images of (d) TPB-DMTP-COF and (e) TPB-DMTP-COF@ILe. Reproducing with permission [128]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

In situ Raman spectroscopy is a powerful optical technology that can measure structural changes during battery operation. It can be used to characterize materials or electrolytes and study the morphological changes of chemical species in electrochemical reduction reactions, reveal the active center and electronic transfer mechanism of reactants, and provide more reaction information [119,120]. For example, Yu et al. [121] reported a two-dimensional polyarylimide COF (PI-COF) anode with excellent Zn2+ storage capacity. The chemical structural changes in PI-COF during Zn2+ storage were studied using in situ Raman spectroscopy and electrochemical method, and it was confirmed that the storage of Zn2+ by PI-COF electrode was divided into two steps. Zheng et al. [122] designed a new COF (BT-PTO—COF) cathode using orthoquinone, which was used to assemble an aqueous zinc organic battery with satisfactory performance. The COF in the 3 mol/L ZnSO4/D2O electrolyte was analyzed using in situ Raman spectroscopy. The regular changes in the peaks in the in situ Raman spectrogram indicated the direct insertion of H+ during the electrochemical reaction process. The formation/dissolution of zinc sulfate hydroxide hydrate was also monitored. The result confirmed that C=O was the active center, indicating the insertion and extraction of Zn2+. Chen et al. [123] designed a two-dimensional COF (TFPB-COF) with ordered mesopores (~2.1 nm) as a high-performance lithium storage material. The prepared two-dimensional imine-based TFPB-COF was stripped to obtain TFPB-COF (E-TFPB-COF) and E-TFPB-COF/MnO2 composites using a chemical method. The stripped TFPB-COF exhibited a new active lithium storage site related to the conjugated aromatic π electrons, greatly improving the performance. To better understand the storage mechanism of lithium, E-TFPB-COF/MnO2 anode was characterized using in situ Raman spectroscopy. The in situ Raman spectroscopy of the anode during complete discharging and charging were observed, during the discharge process, the characteristic peaks of the four main functional groups were gradually weakened, evidencing that lithium storage reaction with the C=N, C=C (conjugated π electron), and Mn-O groups of the C6 ring occurred when lithium-ion migrated into E-TFPB-COF/MnO2 composite. The opposite phenomenon can be observed during charging. The ex-situ FTIR characterization result was similar to the in situ Raman results. Singh et al. [124] combined the thiazole part into the organic scaffold to prepare π conjugated COF electrodes with high crystallinity (the AZO COF connected with thiazole was represented as AZO-1). The obtained COF electrode achieved the coordinated double electron migration of the azo functional group in one step, improving the performance lithium organic battery. In order to further study the main azo oxidation–reduction reaction and the secondary thiazole and electrolyte reactions, the operational Raman spectroscopy was performed on the electrode material. Raman spectroscopy showed the discharge process (3–1 V), and the azo group decreased step by step until it disappeared at 1.2 V. Then, during the charging process, the bond reappeared at 1.5 V and became strong at 2.1 V. The thiazole ring vibration disappeared before the quenching of the azo bond, and it began to recovery at 2.1 V. This feature corresponded to the small thiazole redox wave in the CV and the short potential platform in the constant current spectrum. However, their contribution to the capacity was insignificant. At a more negative voltage, the signal of benzene attenuated at less than 1.5 V and reappeared at 1.8 V, relating to the lithiation of the COF layer through the π-ring-Li+ interaction. Nevertheless, the optical image of the first cycle revealed that the COF electrode had edge volume expansion and contraction, indicating moderate Li+ nesting and de-nesting, respectively. Compared with traditional analysis methods, in situ technology supplies a comprehensive understanding of the charge storage mechanism to guide the exploration of better battery design.

The atomic structure of energy storage materials usually determines their performance. The traditional electron microscope can supply detailed information about materials; however, it cannot directly detect all elements at the atomic scale in the energy storage materials. Scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) techniques that allow imaging of light elements, such as high angle annular dark field (HAADF) imaging, energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, and electron energy loss spectroscopy, have recently gained popularity owing to their ability to disclose high-resolution structure, composition, and bonding information. Thus, STEM has been proven helpful to develop high-performance battery materials [125–127]. Some researchers have applied this method to characterize COFs. For example, Wang et al. [128] used triphenylbenzene (TPB) and dimethoxy-p-benzaldehyde (DMTP) as raw materials to synthesize porous TPB-DMTP-COF. The material was incorporated into polymer ionic liquid/ionic liquid (PIL/IL)-based ionic gel electrolyte (IGE) as a filler with high IL load to improve the ion conductivity of polymer IGE, thus improving the performance of lithium metal battery. The TPB-DMTP-COF was characterized using SEM, TEM, and STEM-HAADF. The SEM image revealed the shape of TPB-DMTP-COF nanospheres with uniform particle size and diameter of about 800 nm. Due to the interaction between layers, the TEM image showed the layer-by-layer stacking structure of nanospheres. STEM-HAADF image (Fig. 6d) revealed regular spherical boundary and elements except the hydrogen. The STEM-HAADF image (Fig. 6e) of TPB-DMTP-COF@IL electrolyte showed uniformly distributed S and F elements, further confirming the interaction between TPB-DMTP-COF and IL. In Chen et al.'s report [123], SEM, TEM, and HAADF-STEM were also used to characterize TFPB-COF, E-TFPB-COF, and exfoliated E-TFPB-COF/MnO2. SEM/TEM images showed the multi-layer stacking structure of TFPB-COF. The laminous structure with fewer layers was observed on the peeled E-TFPB-COF and E-TFPB-COF/MnO2. The HAADF-STEM element mapping image revealed uniform distribution of Mn, N, C, and O in the composite material. Therefore, in situ/operando technology and other more advanced technologies will be widely used in the mechanism research of COF-based batteries in the near future.

4. Application of COFs in ZIBs cathodeGenerally, Prussian blue analogues (PBAs, such as MFe(CN)6, M = Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Mn, …), manganese based oxides (such as Mn3O4, α-/β-/γ-/δ-/λ-MnO2, MnO, and manganese based composites), as well as vanadium based compounds (such as VxOy, metal vanadates, vanadium phosphate, and their composites) are the most traditional cathode materials for rechargeable ZIBs in water systems. PBAs have the advantages of being nontoxic, low-cost, and 3D fast diffusion channels, and are easy to prepare. However, there is the problem of electrode material dissolution during battery charging and discharging, and their performance is low in alkaline environments. Manganese based oxides not only have the advantages of low cost, environmental friendliness, and low toxicity, but also have the characteristics of multivalent states (Mnx, x = 0, 2+, 3+, 4+, and 7+). However, during the cycling process, the unstable phase transition of the manganese-based structure leads to low cycling stability. Vanadium based compounds have abundant resources and diverse valence states, but vanadium is relatively expensive, which limits its application in large-scale energy storage. It is necessary to address the above difficulties of cathode materials in order to improve the performance of ZIBs. Fortunately, these limitations can be overcome using COFs owing to the own advantages of COFs [129–139]. Since Jiang et al. [139] first manufactured a COF-based compound (DTP-ANDI-COF@CNTs) as LIB's cathode material in 2015, many COFs, such as Tp-DANT-COF, Tb-DANT-COF [140], PIBN-G [141], PI-ECOF-1/rGO 50 [142], and BQ1-COF [143] have attracted the attention of researchers. These COFs have significantly improved the electrochemical properties of battery cathodes. This section mainly describes the latest progress of COFs as cathodes for ZIBs.

In 2019, Banerjee et al. [144] synthesized a 2-dimensional covalent organic frame material HqTp-COF through the solid mechanical mixing of 1, 3, 5-triformylphloroglucinol (Tp) and 2, 5-diaminohydroquinone dihydrochloride (Hq). SEM analysis revealed that the synthesized HqTp organic cathode had a layered zonal morphology, and the morphology maintained good stability after the battery was assembled for a charging-discharge cycle. TEM also revealed the presence of CNF nanoparticles, where CNF only improved the conductivity and did not interact with zinc ions. The N—H and C=O groups in HqTp were storage sites of zinc ions. The C=O functional group connected by quinone and the C=O functional group in TP had a stronger affinity for Zn2+ ions than the N—H functional group. The C=O functional group was the main Zn2+ ion storage site. One HqTp cell corresponded with the interaction of 7.5 Zn2+ ions. In addition, HqTp and its crystalline honeycomb structure provided a suitable aperture of 1.5 nm, which effectively promoted the rapid kinetics of Zn2+ ions. HqTp showed a satisfactory discharge capacity of 276 mAh/g at 125 mA/g owing to its abundant active sites and large aperture channels. At an ultrahigh current density of 3750 mA/g, a discharge capacity of 85 mAh/g remained for more than 1000 cycles. The initial capacity and CE remained at 95% and 98%, respectively. According to reports, nitrogen doping or nitrogen substitution can promote the chemical adsorption of Zn2+ ions, improve the specific capacity and cycling stability of electrodes in ZIBs. In 2020, Wang et al. used a phenanthroline COF (PA-COF) as a cathode for a high-performance aquatic zinc-ion supercapattery [145]. The supercapattery is an electrochemical energy storage device that uses capacitive and non-capacitive Faraday charge storage mechanisms [146]. PA-COF was synthesized through solvothermal condensation of hexone cyclohexane with 2, 3, 7, 8-phenazine tetramine. The synthesized PA-COF used the nitrogen-enriched phenanthroline functional group as the active site of the Zn2+ ion, involving the insertion of two cations, Zn2+ and H+. The capacity contributions of Zn2+ in the first three cycles were 54.5%, 61.3%, and 60.0%, with the remaining capacity contributions attributed to H+ ions. The synthesized PA-COF had a medium pore size of 2–5 nm, which can effectively reduce the hindrance during ion insertion. Its rigid conjugated structure made it thermally stable up to 600 ℃, while the weight loss of the COF precursor was severe at 600 ℃. Those advantages enable PA-COF to demonstrate outstanding performance. Electrochemical tests revealed the excellent capacity of 247 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g. At the current density of 1.0 A/g, the average capacity attenuation of each cycle during 10, 000 cycles was 0.38% (Figs. 7a-c). In 2021, Ball et al. conducted a theoretical study of PA-COF using density functional theory (DFT) [147] and calculated some important electrochemical properties of PA-COF, such as diffusion barrier, theoretical storage capacity, and open-circuit voltage (OCVs). The theoretical results were in good agreement with the experimental results of Wang et al. [145]. The designability of the COF structure optimizes the active site and pore size. Ball et al. predicted a new organic covalent framework material QPA-COF based on quinone structure and phenanthroline structure by simply adjusting the organic framework of phenanthroline and proposed a possible synthesis strategy. A theoretical study was conducted on QPA-COF, and the results showed that QPA-COF had semiconductor properties. After the insertion of Zn2+ ions, QPA-COF changed from semiconductor to metal and exhibited good conductivity. The predicted theoretical capacity of QPA-COF was almost twice higher as that of PA-COF, owing to the increased quinone structural active sites of QPA-COF. In addition, the calculation showed that the open-circuit voltage (OCV) of QPA-COF was significantly greater than that of the PA-COF, indicating that QPA-COF had a higher battery voltage than PA-COF. The calculation of the diffusion barrier of zinc atoms on QPA-COF and PA-COF showed that the mobility of zinc ions of the two materials was extremely high and similar.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 7. (a) Charge/discharge distribution and (b) constant-current cycle performance at a current density of 0.1 A/g. (c) Long-term cyclic stability at a current density of 1.0 A/g. Copied with permission [145]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (d) Performance comparison of COF cathodes. | |

In 2022, Zheng et al. discovered a new orthoquinone COF (BT-PTO—COF) using pyrene-4, 5, 9, 10-tetraketone (PTO) monomer with abundant C=O functional group and benzenetricarboxaldehyde (BT) node [122]. The material was synthesized through the Schiff-based solvent thermal condensation reaction of PTO and BT at 120 ℃ for three days. The cathode of rechargeable water-based zinc-ion battery exhibited the charge storage mechanism of co-intercalation of Zn2+ and H+. When the current density reached 200 A/g, the co-insertion route of H+ and Zn2+ evolved into more H+ion insertion. The COF exhibited a high ion diffusion efficiency (~10−8–10−7 cm2/s) owing to its large aperture size (~2.23 nm) and ordered tunnel structure. Electrochemical tests exhibited that the COF exhibited a high capacity of 221 mAh/g at 1 A/g, an extremely high power density of 184 kW/kg, and an energy density of 92.4 Wh/kg. Meanwhile, the capacity of COF was maintained at 98% after 10, 000 cycles. Zhao et al. [148] prepared a TP-PTO—COF through a simple solvent condensation reaction, and the morphology of the synthesized COF was a 2D layered stack shape, adjacent β-keto carbonyl and carbonyl double active sites were very conducive to the storage of Zn2+ ions. In addition, the porous structure and the large specific surface area of 601 m2/g provided an ion diffusion channel, further accelerating the storage of Zn2+ ions. The diffusion coefficient of Zn2+ ions in Tp-PTO—COF cathode was about 10−11 cm2/s, which proved that the COF structure was satisfactory for improving performance. It is well known that the stability of electrode structure is the key to the long-term cycle performance of batteries. The author determined whether the structure of the Tp-PTO—COF cathode was stable by monitoring its morphological evolution during the charging and discharging process. The results showed that there were no significant morphological changes or by-products on the electrode after discharge. Therefore, TP-PTO—COF as a ZIBs cathode exhibited excellent capacity performance of 301.4 mAh/g and ultra long cycle stability, resulting in a capacity of 218.5 mAh/g for 1000 cycles and a CE of approximately 100%. Lin et al. synthesized an all-trans aromatic microporous COF (TAQ-BQ-COF) through a condensation reaction of benzoquinone BQ and TABQ in acetic acid and ethanol [149]. TAQ-BQ-COF had a micropore structure of about 0.58 nm, which improved the volume capacity and volume energy density of the cell and the cation diffusion. TAQ-BQ-COF exhibited satisfactory capacity and cycle stability in 1 mol/L ZnSO4 electrolyte owing to the rich redox active sites of TAQ-BQ-COF. The cycling results showed that the COF exhibited a capacity of 208 mAh/g at 0.1 A/g and maintained a capacity of 136 mAh/g at 2 A/g. In addition, the existence of the anti-aromatic conjugation system endowed TAQ-BQ-COF with a higher redox potential than other reported COF cathodes. Venkatesha et al. [150] explored the use of COF in aqueous ZIBs with mixed ion electrolytes with Zn2+ and Li+ cations. They synthesized DAAQ-TFP-COF using 2, 6-diaminoanthraquinone (DAAQ) and 1, 3, 5-triformylphloroglucinol (TFP) as precursors. The DAAQ-TFP containing original COF was denoted as DAAQ-TFP-COF, while DAAQ-TFP containing graphite oxide (GO) was labeled as COF-GOPHs. The electrochemical properties were tested with 1 mol/L ZnSO4, 1 mol/L Li2SO4, and different proportions of ZnSO4 + Li2SO4 electrolytes. Both the original COF and COF-GOPHs exhibited excellent cycling stability and capacity retention in 0.5 mol/L ZnSO4 + 0.5 mol/L Li2SO4 electrolyte, which was attributed to the optimal Li+ and Zn2+ ion ratio in the electrolyte, thus increasing the overall electrolyte conductivity and promoting the diffusion of Zn2+into porous COFs. The results obtained through experiments and theoretical calculations showed that in mixed ion electrolytes, only Zn2+ ions could reversibly embed into COF and coordinate with carbonyl oxygen and enamine nitrogen, while Li+ ions did not participate in redox reactions. Compared with the original COF, COF-GOPHs exhibited superior performance. The discharge capacity of COF-GOPHs was 220.7 mAh/g, which was about twice that of the original COF, resulting from the enhanced conductivity caused by GO. In most reported organic cathode materials for zinc ion batteries, carbonyl is basically used as the active site for storing zinc ions. However, in water-based electrolytes, carbonyl has high hydrophilicity, which has become a key disadvantage. Peng et al. [151] reported a COF-TMT-BT cathode with a different solid structure from the past. The solid structure of the COF is derived from the irreversible C=C bond, which makes it insoluble in water-based electrolytes. The results of thermogravimetric analysis and differential scanning calorimetry also showed that the COF-TMT-BT had high thermal stability at up to 450 ℃. In addition, COF-TMT-BT had a high surface area of 342.5 m2/g and a pore structure of approximately 3.76 nm, which greatly reduced the hindrance of zinc ions during their movement in the cathode. The most exciting thing was that the electrochemical active group of this novel COF was no longer a carbonyl group but a multifunctional benzothiadiazole group, which contained S and N atoms and can reversibly coordinate with Zn by controlling ion complexation and release. When using this material for ZIBs cathodes, the capacity, energy density, and power density obtained at a current density of 0.1 A/g were satisfactory, with a capacity of up to 283.5 mAh/g, a maximum energy density of 219.6 Wh/kg, and a power density of 23.2 kW/kg. Compared with some organic cathode materials previously reported, this material had better performance. Fig. 7d shows the performance comparison of some COF cathodes in the ZIBs mentioned above. These pioneering studies provide insight into the design of more advanced COF for building promising COF-based ZIBs cathodes.

5. Application of COFs in ZIBs anodeIn ZIBs, the Zn anode releases Zn2+ into the electrolyte during discharge and receives them during charging. ZIBs are considered to be a promising alternatives to LIBs owing to the desirable characteristics of Zn anodes, such as good chemical/physical stability, high volume density (5855 mAh/cm3), environmental friendliness, abundant resources, and low cost. However, Zn anodes have some shortcomings to be addressed. For example, large dendrites form on the Zn anode during battery operation can severely shorten battery life, posing safety problems [38,39]. Researchers have attempted to solve this problem using various methods. Among them, the construction of an artificial interface layer on the Zn anode surface has attracted considerable researchers' attention. However, the migration path of Zn2+ in an ordinary artificial interface layer mainly depends on unordered and random fractures or pores formed through accumulation. The ion transfer kinetics of Zn2+ is still limited because of the lack of inherent ion acceleration channels. Therefore, it is important to design interfacial layers with rich nanopores as ion channels to accelerate the desolubilization of by-products and enhance the Zn2+ ion transfer kinetics [63,64]. COFs have received much attention because of their low molecular weight, high energy density, ordered ion channels, and well-stability [5,62,152]. The application of COFs on the Zn anode as an artificial interface layer to avoid direct touch between the electrolyte and the electrode inhibits the water-based parasitic reaction and homogenizes the Zn2+ flux, thus inducing uniform zinc nucleation deposition and boosting the cycle stability of the Zn anode to some extent. Therefore, the introduction of COFs on Zn anodes to enhance the performance of ZIBs is an effective strategy. This section summarizes the latest research progress of COFs as an protective layer for ZIBs anode.

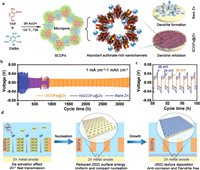

The poor reversibility of metal anode is a key factor affecting the long-term cycle of batteries. The formation of non-planar dendritic morphology during battery charging is the main obstacle to realizing the high reversibility of the zinc anode [153]. In this regard, Wang et al. proposed a synergistic strategy to achieve no Zn dendrite deposition and self-corrosion inhibition by promoting Zn2+ migration kinetics and regulating surface energy. They developed a multifunctional sulfonic acid-rich COF (SCOFs) film covering the Zn anode (denoted as SCOFs@Zn) to extend the cycle life of the zinc anode (Fig. 8a) [154]. Abundant sulfonate-rich nanochannels in SCOFs and the vital interaction between -SO3H and Zn2+ accelerated the transport of Zn2+. At 1 mA/cm2 and 1 mAh/cm2 (Fig. 8b), SCOFs@Zn anode achieved an outstanding reversible stable cycle for 3300 h, while Zn anode without sulfonic COFs (NSCOFs@Zn) showed an internal short circuit resulting from dendrite after 700 h of the cycle and suddenly failed at about 150 h due to local short circuit. The bare Zn had the highest voltage polarization of the three anodes (Fig. 8c) due to the slow plating/peeling behavior of Zn2+ and rampant side effects. The SCOF@Zn significantly reduced the surface energy of the Zn (002) crystal surface and preferentially induced the electroplating growth of crystal (002) orientation (Fig. 8d). The morphology of Zn deposited on the composite anode was uniform and flat hexagonal Zn sheet, which confirmed the improved reversibility of Zn deposition. Thus, the lifespan of the SCOFs@Zn anode was 3000 and 4000 h at 5 mA/cm2 and 2 mAh/cm2 and 5 mA/cm2 and 1 mAh/cm2. At the same time, the full battery maintained significant reversibility over 1000 cycles. SCOFs, as porous material rich in sulfonic acid groups, can improve the reversibility of ZIBs by regulating surface energy and enhancing Zn2+ transfer kinetics. In addition, Zhao et al. prepared an ultra-thin and porous fluorinated COF (FCOF) film with ideal mechanical strength as a protective layer on zinc surface using the solvothermal method [155]. A large number of F atoms were introduced into FCOF films from the viewpoint of surface energy regulation of Zn crystals. By strongly inducing Zn growth along (002) crystal surface through the deposition of FCOF thin film, Zn deposits were shaped similar to small Zn plates, which significantly inhibited the outgrowth of Zn dendrites, thus improving the corrosion resistance and invertibility of Zn anode. For FCOF@Zn, less irreversible by-products of Zn4SO4(OH)6·5H2O accumulated on the anode surface compared with pure Zn anode. The results showed that the use of FCOF film for surface protection significantly boosted the corrosion resistance of the zinc anode. In addition, under the current density of 80 mA/cm2 and the capacity of 1 mAh/cm2, the FCOF@Ti/Zn half-cells exhibited a excellent CE after 320 cycles, which was close to 97.2% on average. In contrast, after 95 cycles, the CE of Ti/Zn half-cells rapidly decreased. Therefore, the FCOF membrane was stable, resistant to parasitic chemical processes during cycling, and exhibited high reversibility. At full battery operation, FCOF@Zn/MnO2 maintained 92% capacity and a stable discharge-charge curve after 1000 cycles at 3 ℃, which was nearly four times that of Zn/MnO2 (capacity retention: 20%). At an ultra-high current density of 0.04 A/cm2, the FCOF@Zn anode maintained over 320 cycles with good reversibility of ~97.2%, and the symmetrical battery exhibited a cycle life of approximately 750 h. This performance is largely attributed to the strong interaction between a large number of electronegativity F atoms in the FCOF layer and Zn atoms, lowering surface energy on the Zn (002) surface compared with that on the traditional Zn (101) surface. The porous nano channels containing F endowed the film with a good hydrophobic effect, which was conducive to solvent removal and rapid transport of hydrated Zn2+.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 8. (a) Schematic illustration of the synthesis and structure of SCOFs and the mechanism of stabilizing the Zn anode. (b) Long-term galvanostatic cycling of symmetric cells using SCOFs@Zn, NSCOFs@Zn, and bare Zn anode at 1.0 mA/cm2 and 1.0 mAh/cm2. (c) Long-term galvanostatic cycling of symmetric cells using SCOFs@Zn, NSCOFs@Zn, and bare Zn anode at a current density of 5.0 mA/cm2. (d) The mechanism of stabilizing the Zn anode. Copied with permission [154]. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH. | |

The corrosion of the ZIBs anode causes a HER, resulting in a unsatisfactory utilization rate of Zn and inferior cycling stability. The formation of zinc dendrites increases the anode surface area and provides more active sites for H2 production. Meanwhile, the by-product of the HER can result in anode surface passivation and corrosion, thus affecting the even deposition of Zn2+ [156]. Therefore, the relationship between surface corrosion and Zn crystal growth must be comprehensively investigated to improve the performance of aqueous cell systems. Zhao et al. deposited COF (TpPa-SO3H) layer containing cationic conductive sulfonic acid on the anode of ZIBs to inhibit dendrites formation and passivation on Zn surface [157]. Through the synergistic action of sulfonic acid groups and Zn2+, the even deposition of Zn2+ was regulated, and the growth of dendrites was inhibited. In addition, the TpPa-SO3H membrane released a large amount of H+; thus, the H+ achieved dynamic balance with OH−, thereby reducing the dissolution energy and hindering the formation of by-products. The nucleation overpotential of the TpPa-SO3H electrode (16 mV) was significantly smaller than that of TpPa@Zn (≈ 81 mV) and naked Zn (≈ 146 mV). Therefore, the TpPa-SO3H film can greatly reduce the Zn nucleation overpotential and local current density of TpPaSO3H@Zn-foil, further inhibiting the Zn dendrite formation [158]. The formation of dendrites leads to the irreversible depletion of the electrolyte and the loss of Zn2+ in the formation of SEI film, resulting in inferior cycling stability [159]. The CE of composite electrode was about 99% after 1000 cycles. The results showed that TpPa-SO3H inhibited the side reaction of the electrolyte, promoted the Zn plating/extraction process, and reached a higher CE. In addition, the TpPa-SO3H@Zn-foil| |MnO2 battery exhibited satisfactory cycle stability and a capacity retention rate of 94.7% after 1000 cycles, while the discharge capacity of the Zn foil| |MnO2 battery rapidly declined after 100 cycles. After 1000 cycles, the CE of TpPa-SO3H@Zn-foil| |MnO2 battery (99.8%) was much higher than that of Zn foil| |MnO2 (80.5%). The TpPa-SO3H@Zn-foil| |MnO2 battery exhibited better cycle stability, indicating that TpPa-SO3H significantly improved the performance of ZIBs. Moreover, Hu et al. reported a highly crystalline alkynyl-based COF (COF−H), which was fabricated using aniline as an optimal modulator. Additionally, aniline was coated on zinc anodes to inhibit the corrosion reaction and dendrite formation in ZIBs [159]. The compound had a large specific surface area, and good stability in strong alkali and acid media. The even distribution of Zn2+ in channels and the strong affinity of alkyl, enamine, and ketone in COF-H for Zn2+effectively suppressed the growth of Zn dendrites, thus endowing the Zn anode with a long cycle life of larger than 900 h at 3 mA/cm2, thereby booosting the cyclic stability of the COF@Zn| |MnO2 full battery. Similarly, Park et al. covered Zn electrodes with ultra-thin COF layers using direct and scalable dipping techniques. The ultra-thin COF layers inhibited surface corrosion and large Zn dendrites formation by allowing efficient mass and charge transfer [6,160]. The COF films had a strong affinity for Zn2+, in which imine functional groups and electron-rich ketones facilitated interactions with Zn2+ [161] and accelerated the transport of the ions via the site–site jumping mechanisms. In Zn||Zn double electrode structure, the voltage distribution of bare Zn was much larger than that of COF@Zn, revealing significant differences in the nucleation overpotential. This result showed that COF@Zn was a suitable material for the initial zinc deposition because the lower the nucleation overpotential, the lower the energy barrier of zinc deposition. For unmodified zinc, sharp nucleation overpotential profiles indicated the fast formation of heterogeneous zinc nuclei and their transformation into dendrites. For COF@Zn, the smaller the nucleus, the more uniform and evenly distributed the growth of Zn dendrites. These results show that COF layers can "homogenize" the Zn2+ flux and restrain the formation of Zn dendrites during electrochemical cycling. In COF@Zn||the δ-MnO2 full battery, the location of the redox peak slightly moved because of the reversibility and kinetic improvement (the gap between the redox peak decreased), indicating that the COF package membrane can effectively inhibit surface corrosion and passivation, thus improving the utilization rate of Zn. The battery exhibited good capacity retention and relatively stable polarization voltage, and cycling at 1 mA/cm2 for over 420 h. Moreover, due to deficiently contact with electrolyte and the limited surface area, the planar Zn anode produced uneven current density and ion concentration, forming Zn dendrites, which limited the further development of high-performance Zn anode. Compared with planar anodes, three-dimensional anodes have a highly stable skeleton structure, protecting the anode shape from changing or preventing structural collapse during plating and stripping cycles. Furthermore, three-dimensional anodes provided wider channels, facilitating charge and ion transport and providing a large reaction surface area and abundant nucleation sites, thus inducing a uniform distribution of Zn2+ on the Zn anodes. Side reactions can be minimized by selectively accelerating cationic transport and inhibiting anion migration, and dendrite growth can be inhibited by ensuring uniform plating/stripping of Zn2+. Wu et al. designed and in situ synthesized an ultra-thin homogeneous three-dimensional -COOH-functionalized COF film (3D-COOH—COF) with excellent mechanical strength to preserve anodes [69]. Owing to its unique structure as well as rich COOH functional groups, the COF film enable the fast transport of Zn2+ and hinder the transport of SO42−. The transport behavior of Zn2+ and SO42−anions in ZnSO4 solution in 3D-COOH—COF layer was studied using molecular dynamics simulation. As visualized in Fig. 9a, Zn2+ passed through 3D-COOH—COF films, while SO42− were blocked due to 3D-COOH—COF-abundant electronegative backbone and microporous channels. Diffusion channels in 3D-COOH—COF membranes were simulated to make further efforts to explore the migration behavior of Zn2+ in 3D-COOH—COF membranes (Figs. 9b and c). The results showed that the Zn2+ diffusion energy potential along the optimized path was 0.1337 eV, which was smaller that of Zn or Zn-ionized water cells previously reported, further confirming that 3D-COOH—COF protective membrane facilitated the migration of Zn2+ and uniform distribution of Zn2+ [162,163]. In addition, the membrane ionic conductivity, initial current (I0) and stationary current (Iss), and Zn2+ migration number (tZn2+) of the 3D-COOH—COF were relatively higher (Figs. 9d-f). The growth of zinc dendrites was more inhibited with increased cation migration [164]. The zeta potential curve revealed that the high Zn2+ migration rates resulted from a strongly electronegative functional group. The group not only effectively adsorb Zn2+ but also have a excellent sealing effect on anions. Therefore, the protective coating can significantly boost the rapid migration of Zn2+, restrain the migration of anions, and restrain the growth of Zn dendrites. Fig. 9g exhibits the cyclic performance of the full cell at 1 A/g. For 3D-COOH—COF-protected zinc anode, the capacity was 163.61 mAh/g after 500 cycles, and the retention rate of capacity was 78.7% compared with the second cycle. On the contrary, the electrochemical performance of the naked zinc anode was poor, and its capacity retention rate was below 32 mAh/g after 250 cycles. Therefore, the protective layer of 3D-COOH—COF can greatly restrain the side reaction between the zinc anode and electrolyte and inhibit the zinc dendrites formation in the whole cell by selectively accelerating ion transport and uniformly regulating ion deposition. Replacing planar electrodes with 3D anodes is an efficient and direct method to increase the electrolyte–anode interface area.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 9. (a) Molecular dynamics simulations of Zn2+ and SO42− ions to pass through the 3D-COOH—COF film. (b) The optimized Zn-ion diffusion pathway in the 3D-COOH—COF layer. (c) The corresponding migration energy barrier. (d) Ionic conductivity of OH—COF precursor@Zn and 3D COOH—COF@Zn. (e) Current variations in bare Zn, OH—COF precursor@Zn, and 3D-COOH—COF@Zn in symmetric cell with a potentiostatic polarization. (f) The Zn2+ transference number in the cells using bare Zn, OH—COF precursor@Zn, and 3D-COOH—COF@Zn electrodes. (g) Galvanostatic charge/discharge curves of bare Zn||MnO2 and 3D-COOH—COF@Zn||MnO2 cells. Copied with permission [69]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. | |

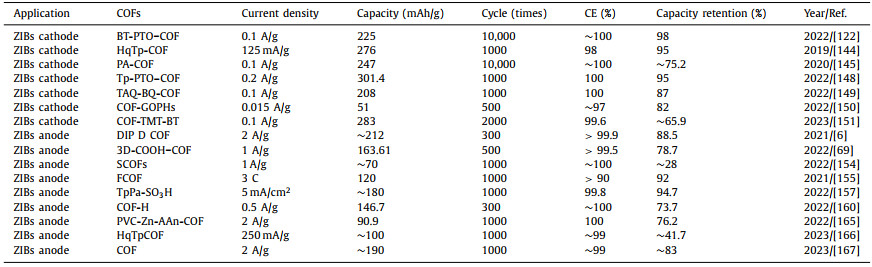

ZIBs are extremely prospective large-scale energy storage equipments. Thus, it is necessary to summarize the current challenges facing ZIBs and the corresponding solutions. In this paper, the basic issues hindering the commercialization of ZIBs are first reviewed, especially the anode and cathode. Generally, the Zn anode is mainly characterized by dendritic growth, severe corrosion, and complex side reactions, while the conventional cathode is characterized by low capacity, slow diffusion of Zn2+, and structural collapse. Subsequently, the synthesis and characterization techniques of COFs were briefly introduced. Finally, the progress of COFs in developing the cathode and anode of ZIBs was elucidated, and the performance of COF electrodes in ZIBs was also summarized (Table 1). COFs can accelerate ion conduction, induce uniform ion deposition, and inhibit the growth of dendrites [165–167]. The highly crystalline π-π conjugated structure of COFs is conducive to the stable operation of the battery under the condition of variable cathode and anode polarization, indicating that COFs can effectively handle the problems faced by the cathode and anode of ZIBs. However, the exploration of COFs in batteries is still in its initial stage, with many challenges remaining to be solved (Fig. 10).

|

|

Table 1 Summary of COF cathodes and anodes in ZIBs in recent years. |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 10. Outlook for the future development of COFs in batteries. | |

First, due to the dynamic bonding and weak interlayer interactions of COFs, their conductivity and stability are not ideal. Weak conductivity can slow the transport of ions during battery operation, thereby affecting the rate performance of the battery; poor stability greatly limits the selection of electrolyte and is insufficient to cope with changes in the physical and chemical environment inside the battery during operation. At present, there is a way to improve the conductivity and stability of COFs by hybridization. However, this method will reduce the concentration of active substances, thereby reducing energy density and weight specific capacity. Therefore, improving the conductivity and stability of COFs without sacrificing the concentration of active substances is still a major issue that needs to be addressed. Second, most of the COFs currently reported for use in ZIBs as anodes are two-dimensional COFs constructed by coating or using polymer binders. This method can easily affect the pore size and pore distribution of COFs, which not only makes it difficult to control the pore size of COFs, but also poses difficulties for the uniform transport of Zn2+. In comparison, three-dimensional COFs synthesized through in-situ growth have more advantages. The 3D-COFs synthesized by in-situ growth have uniform pore size and distribution, which not only accelerates the transport speed of Zn2+, but also suppresses the insertion/detachment of unrelated ions by designing the pore size of COFs reasonably. In addition, more active site exposed by 3D-COFs can improve the storage of Zn2+, thus improving the battery capacity. Therefore, promoting the use of 3D-COFs in ZIBs should be a better way to solve the current problems faced by ZIBs. Third, the stacked COFs increase the diffusion path of Zn2+, resulting in slow diffusion of Zn2+ and reduced ion transport kinetics. In addition, it may cause difficulties in obtaining and utilizing redox active site, leading to the reduction of battery capacity. In order to solve these problems, layering large blocks of COFs into several layers of COFs has been proved to be an effective way to improve Zn transfer kinetics and expose more redox active site. However, large-scale stripping of multi-layer COFs into monolayer COFs still poses challenges. Fourth, the relationship between the structure, composition, morphology, and corresponding electrochemical performance of COF requires in-depth research using advanced in-situ characterization methods and high-level theoretical calculations. A deeper understanding of COFs is necessary to make better use of them. For example, machine learning can be conducted for battery diagnosis and predicting battery life and high-throughput calculation can be used to calculate the energy density, voltage, and volume change of ZIBs. Moreover, safety has always been an important index for evaluating ion batteries. In selecting electrode materials and electrolytes, the first principles can be used to calculate the formation energy and migration energy of material defects to predict the phase stability, thus reducing the possibility of accidents. Fifth, COFs can be used to alleviate the problems faced by the anode and cathode of ZIBs. However, the current evaluation of ZIBs modified with COFs is usually limited to coin-type batteries. Moreover, most evaluations are based on proof of concept without in-depth research. We believe that in future research, commercial bag batteries and cylindrical batteries will be used to comprehensively assess the performance of COF-modified batteries. The performance evaluation of a full battery should include bending, drop, puncture, high and low temperature, cycling, and safety tests. Finally, to boost the performance of ZIBs, the relationship between the cathode and anode, electrolyte, and diaphragm of the battery must be considered. The synchronous improvement and coordination of each component are prerequisites for achieving high performance and high efficiency of the battery.

In summary, COFs offer new opportunities for building organic cells and are characterized by customizable composition, crystal structure, ordered cavity, and high surface area compared with other organic materials. The high specific surface area of the COFs not only promotes interfacial contact between the electrode and the electrolyte, but also exposes more active sites, therefore the zinc ion is easily coordinated with the redox active site to improve the storage of Zn2+ per unit area. And due to its crystal structure, COFs can provide uniformly distributed Zn2+ hopping pathways, and their porosity allows them to form rich Zn2+hopping sites, thereby minimizing the formation of dendrites. Moreover, COFs be applied to the electrolyte and diaphragm of ZIBs and other metal ion batteries (such as Na-ion and K-ion batteries) to improve battery performance. However, the application of COFs in batteries is still in the initial stage and is faced with many challenges, which can be addressed through experimental and theoretical studies, enabling the large-scale production of COF-based batteries.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 61904073), Spring City Plan-Special Program for Young Talents (No. ZX20210014), Yunnan Talents Support Plan for Yong Talents, Yunnan Local Colleges Applied Basic Research Projects (No. 202101BA070001–138), Frontier Research Team of Kunming University 2023, and Key Laboratory of Artificial Microstructures in Yunnan Higher Education.

| [1] |

P. Lokhande, S. Kulkarni, S. Chakrabarti, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 473 (2022) 214771. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214771 |

| [2] |

X. Wei, Y. Song, L. Song, X. Liu, et al., Small 17 (2021) 2007062. DOI:10.1002/smll.202007062 |

| [3] |

S. Wang, C. Tang, Y. Huang, J. Gong, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3802-3808. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.11.037 |

| [4] |

Q. Dai, L. Li, K. Tuan, et al., J. Energy Storage 55 (2022) 105397. DOI:10.1016/j.est.2022.105397 |

| [5] |

D. Zhu, G. Xu, Y. Li, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (2021) 2100505. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202100505 |

| [6] |

J. Park, M. Kwak, C. Hwang, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2101726. DOI:10.1002/adma.202101726 |

| [7] |

R. Zhang, Z. Wu, Z. Huang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2022) 107600. |

| [8] |

Y. Song, L. Zou, C. Wei, Y. Zhou, Y. Hu, Carbon Energy 5 (2023) e286. DOI:10.1002/cey2.286 |

| [9] |

L. Zhang, Y. Hou, Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (2021) 2003823. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202003823 |

| [10] |

Y. Yu, S. Hu, Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3277-3287. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.04.049 |

| [11] |

Y. Liu, Z. Li, Y. Han, et al., ChemSusChem 16 (2023) e202202305. DOI:10.1002/cssc.202202305 |

| [12] |

T. Jin, X. Ji, P.F. Wang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 119433. |

| [13] |

A. Naveed, T. Rasheed, B. Raza, et al., Energy Storage Mater. 44 (2022) 206-230. DOI:10.1016/j.ensm.2021.10.005 |

| [14] |

X. Han, T. Wu, L. Gu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107594. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.06.017 |

| [15] |

W. He, S. Zuo, X. Xu, et al., Mater. Chem. Front. 5 (2021) 2201-2217. DOI:10.1039/D0QM00693A |

| [16] |

H. Hong, X. Guo, J. Zhu, et al., Sci. China. Chem. (2023). DOI:10.1007/s11426-023-1558-2 |

| [17] |

Y. Liu, Q. Li, X. Zhang, et al., Ceram. Int. 49 (2023) 27506-27513. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.06.026 |

| [18] |

X. Li, H. Cheng, H. Hu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 3753-3761. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.04.045 |

| [19] |

X. Cao, Y. Xu, B. Yang, et al., J. Alloys Compd. 896 (2022) 162785. DOI:10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.162785 |

| [20] |

M. Al-Amin, S. Islam, S.U.A. Shibly, S. Iffat, Nanomaterials 12 (2022) 3997. DOI:10.3390/nano12223997 |

| [21] |

Z. Yi, G. Chen, F. Hou, L. Wang, J. Liang, Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (2021) 2003065. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202003065 |

| [22] |

N. Guo, W. Huo, X. Dong, et al., Small Methods 6 (2022) 2200597. DOI:10.1002/smtd.202200597 |

| [23] |

S. Chen, H. Wang, M. Zhu, et al., Nanoscale Horiz. 8 (2023) 29-54. DOI:10.1039/D2NH00354F |

| [24] |

C. Liu, X. Xie, B. Lu, J. Zhou, S. Liang, ACS Energy Lett. 6 (2021) 1015-1033. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.0c02684 |

| [25] |

J. Zhou, Y. Mei, F. Wu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202304454. DOI:10.1002/anie.202304454 |

| [26] |

Q. Li, D. Wang, B. Yan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202202780. DOI:10.1002/anie.202202780 |

| [27] |

Q. Li, X. Ye, H. Yu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2663-2668. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.09.091 |

| [28] |

R. Huang, W. Wang, C. Zhang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 3955-3960. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.11.094 |

| [29] |

I.R. Tay, J. Xue, W.S.V. Lee, Adv. Sci. (2023). DOI:10.1002/advs.202303211 |

| [30] |

Y. Niu, D. Wang, Y. Ma, L. Zhi, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 1430-1434. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.058 |

| [31] |

W. Li, Y. Ma, H. Shi, K. Jiang, D. Wang, Adv. Funct. Mater. 32 (2022) 2205602. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202205602 |

| [32] |

B. Wu, Y. Mu, Z. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107629. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.06.052 |

| [33] |

W. Deng, C.F. Sun, J. Phys. Chem. C 127 (2023) 11902-11910. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcc.3c03583 |

| [34] |

H. Wang, Q. Wu, L. Cheng, G. Zhu, Coord. Chem. Rev. 472 (2022) 214772. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214772 |

| [35] |

Y. Liu, Y. Li, X. Huang, et al., Small 18 (2022) 2203061. DOI:10.1002/smll.202203061 |

| [36] |

K. Nam, S. Park, R. Reis, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4948. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12857-4 |

| [37] |

J. Zheng, Z. Huang, F. Ming, et al., Small 18 (2022) 2200006. DOI:10.1002/smll.202200006 |

| [38] |

D. Song, C. Hu, Z. Gao, et al., Materials (Basel) 15 (2022) 5837. DOI:10.3390/ma15175837 |

| [39] |

Z. Zhang, B. Xi, X. Ma, et al., SusMat 2 (2022) 114-141. DOI:10.1002/sus2.53 |

| [40] |

Z. Qi, T. Xiong, Z. Yu, et al., J. Power Sources 558 (2023) 232628. DOI:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2023.232628 |

| [41] |

H. Ying, P. Huang, Z. Zhang, et al., Nano-Micro Lett. 14 (2022) 180. DOI:10.1007/s40820-022-00921-6 |

| [42] |

X. Chen, H. Su, B. Yang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108487. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108487 |

| [43] |

H. Peng, Y. Fang, J. Wang, et al., Matter 5 (2022) 4363-4378. DOI:10.1016/j.matt.2022.08.025 |

| [44] |

Y. Wang, Z. Wang, W. Pang, et al., Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 2720. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-38384-x |

| [45] |

L. Li, S. Jia, Z. Cheng, C. Zhang, ChemSusChem 16 (2023) e202202330. DOI:10.1002/cssc.202202330 |

| [46] |

K. Feng, D. Wang, Y. Yu, Molecules 28 (2023) 2721. DOI:10.3390/molecules28062721 |

| [47] |

W. Yang, W. Yang, Y. Huang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 4628-4634. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.12.049 |

| [48] |

H. Zhang, C. Gu, M. Yao, S. Kitagawa, Adv. Energy Mater. 12 (2022) 2100321. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202100321 |

| [49] |

J. Li, N. Luo, F. Wan, et al., Nanoscale 12 (2020) 20638-20648. DOI:10.1039/D0NR03394D |

| [50] |

Y. Jiao, L. Kang, J. Gair, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 22075-22082. DOI:10.1039/D0TA08638J |

| [51] |

B. Li, S. Zhang, B. Wang, et al., Energy Environ. Sci. 11 (2018) 1723-1729. DOI:10.1039/C8EE00977E |

| [52] |

R. Shah, S. Ali, F. Raziq, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 477 (2023) 214968. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214968 |

| [53] |

D.-H. Yang, Y. Tao, X. Ding, B.H. Han, Chem. Soc. Rev. 51 (2022) 761-791. DOI:10.1039/D1CS00887K |

| [54] |

S. Huang, K. Chen, T. Li, Coord. Chem. Rev. 464 (2022) 214563. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214563 |

| [55] |

H. Qian, Y. Wang, X. Yan, Trends Analyt. Chem. 147 (2022) 116516. DOI:10.1016/j.trac.2021.116516 |

| [56] |

A. Esrafili, A. Wagner, S. Inamdar, A. Acharya, Adv. Healthcare Mater. 10 (2021) 2002090. DOI:10.1002/adhm.202002090 |

| [57] |

M. Wu, Y. Yang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 1135-1143. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2017.03.026 |

| [58] |

Z. Zhou, L. Zhang, Y. Yang, et al., Nat. Chem. 15 (2023) 841-847. DOI:10.1038/s41557-023-01181-6 |

| [59] |

S. Talekar, Y. Kim, Y. Wee, J. Kim, Chem. Eng. J. 456 (2023) 141058. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2022.141058 |

| [60] |

D. Yang, Y. Tao, X. Ding, B. Han, Chem. Soc. Rev. 51 (2022) 761-791. DOI:10.1039/D1CS00887K |

| [61] |

R. Freund, O. Zaremba, G. Arnauts, et al., Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 23975. DOI:10.1002/anie.202106259 |

| [62] |

L. Guo, J. Zhang, Q. Huang, W. Zhou, S. Jin, Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2856-2866. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.065 |

| [63] |

P. Xiong, Y. Zhang, J. Zhang, et al., Energy Chem. 4 (2022) 100076. DOI:10.1016/j.enchem.2022.100076 |

| [64] |

G. Ren, F. Cai, S. Wang, Z. Luo, Z. Yuan, RSC Adv. 13 (2023) 18983-18990. DOI:10.1039/D3RA01414B |

| [65] |

X. Ren, X. Wang, W. Song, F. Bai, Y. Li, Nanoscale 15 (2023) 4762-4771. DOI:10.1039/D2NR07228A |

| [66] |

P. Qi, J. Wang, H. Li, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 840 (2022) 156529. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.156529 |

| [67] |

Q.N. Tran, H.J. Lee, N. Tran, Polymers 15 (2023) 1279. DOI:10.3390/polym15051279 |

| [68] |

W. Wang, V. Kale, Z. Cao, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2103617. DOI:10.1002/adma.202103617 |

| [69] |

K. Wu, X. Shi, F. Yu, et al., Energy Stor. Mater. 51 (2022) 391-399. |

| [70] |

J. Segura, S. Royuela, M. Ramos, Chem. Soc. Rev. 48 (2019) 3903-3945. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00978C |

| [71] |

X. Han, C. Yuan, B. Hou, et al., Chem. Soc. Rev. 49 (2020) 6248-6272. DOI:10.1039/D0CS00009D |

| [72] |

Z. Mu, Y. Zhu, B. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2022) 5145-5154. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c00584 |

| [73] |

Y. Yusran, Q. Fang, S. Qiu, Isr. J. Chem. 58 (2018) 971. DOI:10.1002/ijch.201800066 |

| [74] |

A. Bagheri, N. Aramesh, J. Mater. Sci. 56 (2021) 1116-1132. DOI:10.1007/s10853-020-05308-9 |

| [75] |

T. Wang, Y. Zhang, Z. Wang, et al., Dalton Trans. (2023). DOI:10.1039/D3DT01684F |

| [76] |

X. Wu, X. Zhang, Y. Li, et al., J. Mater. Sci. 56 (2021) 2717-2724. DOI:10.1007/s10853-020-05380-1 |

| [77] |

B. Bai, D. Wang, L. Wan, Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 94 (2021) 1090-1098. DOI:10.1246/bcsj.20200391 |

| [78] |

K. Geng, T. He, R. Liu, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 8814-8933. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00550 |

| [79] |

Y. Gong, X. Guan, H. Jiang, Coord. Chem. Rev. 475 (2023) 214889. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214889 |

| [80] |

J. Colson, A. Woll, A. Mukherjee, et al., Science 332 (2011) 228-231. DOI:10.1126/science.1202747 |

| [81] |

A. Halder, M. Ghosh, S. Bera, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 10941-10945. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b06460 |

| [82] |

S.L. Zhang, Z.C. Guo, K. Xu, Z. Li, G. Li, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15 (2023) 33148-33158. DOI:10.1021/acsami.3c05990 |

| [83] |

X. Feng, L. Chen, Y. Dong, D. Jiang, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 1979-1981. DOI:10.1039/c0cc04386a |

| [84] |

W. Ji, Y. Guo, H. Xie, et al., J. Hazard. Mater. 397 (2020) 122793. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122793 |

| [85] |

H. Wei, S. Chai, N. Hu, et al., Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 12178-12181. DOI:10.1039/C5CC04680G |

| [86] |

S. Ding, W. Wang, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 548-568. DOI:10.1039/C2CS35072F |

| [87] |

P. Kuhn, M. Antonietti, A. Thomas, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47 (2008) 3450-3453. DOI:10.1002/anie.200705710 |

| [88] |

X. Yang, L. Gong, K. Wang, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) 2207245. DOI:10.1002/adma.202207245 |

| [89] |

S. Chandra, S. Kandambeth, B.P. Biswal, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 17853-17861. DOI:10.1021/ja408121p |

| [90] |

B.P. Biswal, S. Chandra, S. Kandambeth, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135 (2013) 5328-5331. DOI:10.1021/ja4017842 |

| [91] |

K. Dey, M. Pal, K. Rout, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139 (2017) 13083-13091. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b06640 |

| [92] |

M. Matsumoto, L. Valentino, G. Stiehl, et al., Chem 4 (2018) 308-317. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2017.12.011 |

| [93] |

Q. Hao, C. Zhao, B. Sun, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 12152-12158. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b07120 |

| [94] |

L. Beagle, Q. Fang, L. Tran, et al., Mater. Today 51 (2021) 427-448. DOI:10.1016/j.mattod.2021.08.007 |

| [95] |

J. He, L. Yu, Z. Li, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 629 (2023) 428-437. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2022.09.036 |

| [96] |

H. Yang, H. Wu, Y. Zhao, et al., Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 19328-19336. DOI:10.1039/D0TA07352K |

| [97] |

Y. Yang, Y. Chen, F. Izquierdo-Ruiz, et al., Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 220. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-35931-4 |

| [98] |

J. Xiao, J. Chen, J. Liu, H. Ihara, H. Qiu, Green Energy Environ. 8 (2023) 1596-1618. DOI:10.1016/j.gee.2022.05.003 |

| [99] |

Y. Chen, W. Li, X. Wang, et al., Material. Chem. Front. 5 (2021) 1253-1267. DOI:10.1039/D0QM00801J |

| [100] |

J.A. MartinIllan, D. Rodriguez San Miguel, C. Franco, et al., Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 6704-6707. DOI:10.1039/D0CC02033H |

| [101] |

F. van Rantwijk, R.A. Sheldon, Chem. Rev. 107 (2007) 2757-2785. DOI:10.1021/cr050946x |

| [102] |

A. Zheng, T. Guo, F. Guan, et al., Trends Anal. Chem. 119 (2019) 115638. DOI:10.1016/j.trac.2019.115638 |

| [103] |

J. Qiu, P. Guan, Y. Zhao, et al., Green Chem. 22 (2020) 7537-7542. DOI:10.1039/D0GC02670K |

| [104] |

L. Huang, J. Yang, Y. Asakura, Q. Shuai, ACS Nano 17 (2023) 8918-8934. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.3c01758 |

| [105] |

M. Cui, X. Meng, Nanoscale Adv. 2 (2020) 5516. DOI:10.1039/D0NA00573H |

| [106] |

T. Zhou, L. Zhu, L. Xie, et al., J. Colloid Interface Sci. 605 (2022) 828-850. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.07.138 |

| [107] |

C. Wang, Z. Song, P. Shi, et al., Nanoscale Adv. 3 (2021) 5222. DOI:10.1039/D1NA00523E |

| [108] |

E. Fan, Z. Wang, J. Lin, et al., Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 7020-7063. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00535 |

| [109] |

X. Li, X. Yang, J. Zhang, Y. Huang, B. Liu, ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 2521-2531. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b04937 |

| [110] |

X. Cao, C. Ma, L. Luo, et al., Adv. Fiber Mater. (2023). DOI:10.1007/s42765-023-00278-4 |

| [111] |

J. Um, S.H. Yu, Adv. Energy Mater. 11 (2021) 2003004. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202003004 |

| [112] |

A. Tripathi, W.N. Su, B. Hwang, Chem. Soc. Rev. 7 (2018) 736-851. DOI:10.1039/c7cs00180k |

| [113] |

M. Chen, W. Hua, J. Xiao, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 18091-18102. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c06727 |

| [114] |

J. Song, X. Sun, L. Ren, et al., J. Electrochem. 28 (2022) 2108461. |

| [115] |

J. Chen, Y. Yang, Y. Tang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 33 (2023) 2211515. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202211515 |

| [116] |

J. Tian, T. Jiang, L. Zhang, et al., Small Methods 4 (2019) 1900467. |

| [117] |

R. Shi, L. Liu, Y. Lu, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 178. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-13739-5 |

| [118] |

Y. Cai, Z. Gong, Q. Rong, et al., Appl. Surf. Sci. 594 (2022) 153481. DOI:10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153481 |

| [119] |

Y. Matsuda, N. Kuwata, T. Okawa, et al., Solid State Ion 335 (2019) 7-14. DOI:10.1016/j.ssi.2019.02.010 |

| [120] |

K.A. Niherysh, J. Andzane, M.M. Mikhalik, et al., Nanoscale Adv. 3 (2021) 6395. DOI:10.1039/D1NA00390A |

| [121] |

M. Yu, X. Lu, C. Liang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 19570-19578. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c07992 |

| [122] |

S. Zheng, D. Shi, D. Yan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202117511. DOI:10.1002/anie.202117511 |