Carbon dots (CDs) are fluorescent carbon nanoparticles that are less than 10 nm in size and are mainly composed of sp2 and sp3 carbon as well as surface-modified functional groups. Numerous experts have been interested in it since it was initially identified in 2004 [1]. In general, carbon quantum dots (CQDs) and graphene quantum dots (GQDs) are also CDs depending on their nuclear structure and morphology [2]. Among them, CQDs mainly refer to carbon nanostructures with a diameter of less than 10 nm and a quantum confinement effect. GQDs are nanostructures made of single layer graphene or a few atomic layers of graphene. They typically have a size smaller than 20 nm and a thickness generally less than 5 layers of graphene. CDs have numerous distinct advantages over conventional quantum dots. For instance, there are a variety of low-cost raw ingredients with good thermal and photostability and low toxicity [3-6]. Therefore, it has been successfully applied to different fields, including ion sensors, bioimaging, anti-counterfeiting and so on [7-9]. In recent years, it has also been developed and used in emerging fields such as electroluminescent light-emitting diodes, energy conversion and storage [10].

However, as the research progressed, it was found that the properties of CDs, which consist of only carbon and oxygen elements, exhibited certain disadvantages. Because the epoxy and carboxyl groups on the surface induce nonradiative complexation of localized electron-hole pairs and suppress pristine emission, their fluorescence quantum yields (QYs) are generally low [11]. In addition, they usually exhibit monochromatic fluorescence emission. More importantly, the majority of prepared CDs emit blue or green short wavelength fluorescence when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation, which has low penetration depth in biological applications and cannot completely rule out interference from biological tissue's own fluorescence, thus severely restricting the application. To this end, researchers have created a number of strategies to improve the properties of CDs. Currently, heteroatom doping is considered to be a relatively intuitive method to modulate the properties of CDs in recent years. Heteroatom doping comprises metal ion and nonmetal atom doping. Compared to the toxicity of metal ions, the doping of CDs by nonmetal atoms, such as N, S, P, and B, has been more widely reported [12-15]. Heteroatom doping can effectively adjust the intrinsic structure and electron distribution of CDs. By introducing various atoms into CDs, the electronic structure of CDs can be adjusted to generate n-type or p-type carriers, which is an effective method to improve the optical properties and adjust the electronic characteristics of CDs [4].

Among the many dopants, boron atoms are effectively doped for the following reasons: First, boron is adjacent to carbon in the periodic table of elements, and the atomic radius is similar to that of carbon; thus they have similarities in structure and physicochemical properties, so the doping of boron can improve the defects of CDs and improve the optical properties [16]. Second, unlike doped elements such as N and S, boron atoms are less electronegative than carbon, and doping boron atoms into CDs leads to a distribution of positive charges around the carbon atoms [17]. Third, unlike n-type heteroatom dopants such as P, S, and F, boron atoms are p-type dopants that can suppress nonradiative transitions through electron absorption effects. The fluorescence intensity or QY can be greatly improved by boron doping [18]. Based on the effective doping of boron atoms, there have been numerous studies to improve the performance of CDs by boron-doping in recent years. In 2014, Feng et al. synthetized fluorescent boron-doped CQDs (BCQDs) via a bottom-up solvothermal approach. It was found that the BCQDs had a maximum QY of 14.8%, much higher than the 3.4% of undoped CQDs. Doping boron into CQDs can greatly enhance fluorescence [19]. In 2015, Lu et al. synthesized boron-doped CDs from boric acid and ethylenediamine by a simple green hydrothermal method. The yield of the obtained boron-doped CDs was approximately 50%, and showed excellent aqueous solubility and high fluorescence not only in the solid-state but also in aqueous solutions. Based on its excellent solid-state fluorescence and biocompatibility, it has been successfully applied to light-emitting diode (LED) and cell imaging [20]. In addition, during the study of boron-doped CDs, it was found that boron is less electronegative than carbon, nitrogen is more electronegative than carbon, and boron and nitrogen have atomic radii similar to carbon. Therefore, the co-doping of boron and nitrogen can regulate the physicochemical properties of CDs more effectively. The fluorescence properties are enhanced by further boron doping because it alters the arrangements of the C and N atoms as well as the surface functional groups [21]. In 2022, Fechine et al. used citric acid, branched poly ethylenimine and boric acid as raw materials to prepare boron and nitrogen co-doped CDs (B, N-CDs) by a hydrothermal method. The QY of B, N-CDs was 44.3%, which was significantly higher than that of CDs, B-CDs and N-CDs. This is due to the synergistic effect of boron and nitrogen resulting in greater fluorescence enhancement. The surface defects and QY of B, N-CDs in combination with nitrogen functionalization are both increased by boron doping [22]. Numerous investigations have demonstrated that adding boron atoms to CDs can significantly increase their performance. As a result, a summary of the reports on boron-doped CDs is needed.

To the best of our knowledge, there is no review reported on boron-doped CDs. In this review, we will summarize the relevant studies on boron-doped CDs in recent years. We focus on the different doping strategies of boron-doped CDs. Starting from the doping strategies of single boron atom doping and boron and other atom co-doping, we introduce boron-doped CDs in detail from different raw materials to different methods and applications. In the single boron doping strategy, we discuss both a single precursor and multiple precursors. In the section on multiple precursors, we introduce the one-step synthesis of single boron-doped CDs using boric acid, borax and other boron-containing compounds as boron sources and the multistep synthesis of single boron-doped CDs. Different synthesis methods are discussed. In the strategy of boron and other atom co-doping, we mainly discuss boron and nitrogen co-doping and expand from the two aspects of a single precursor and multiple precursors. In the section on multiple precursors, we introduce the one-step synthesis of B, N-CDs using boric acid and other boron-containing compounds as boron sources and the multistep synthesis of B, N-CDs. In addition, boron and multiatom co-doping CDs are briefly discussed. In addition, we will also summarize the effects of boron doping on the different performances of CDs, mainly including fluorescence performance, phosphorescent performance, and catalytic performance. The applications of boron-doped CDs in optical sensors, information security and anti-counterfeiting are briefly introduced. Finally, the research status of boron-doped CDs is summarized and future research is discussed.

2. Doping strategies of boron-doped CDsIn the current study, the doping strategies of boron-doped CDs mainly include single boron atom doping to improve the performance of CDs and boron and other atom co-doping to further improve the performance of CDs through the synergistic effect of different atoms. The most commonly reported in co-doping is boron and nitrogen co-doping, where the synergistic effect of boron and nitrogen greatly improves the fluorescence performance, and the additional boron doping can further increase the fluorescence intensity of nitrogen-doped CDs. In this section, the research progress of boron-doped CDs will be introduced in detail from different aspects, including different precursors and different synthesis methods, starting from different doping strategies of single boron doping and co-doping of boron and other atoms.

2.1. Single boron dopingIn the periodic table, boron is the left neighbor of the carbon atom. Similar to other atoms such as N and S, boron can also be doped into CDs as an effective dopant. Boron is a p-type dopant and has a radius similar to that of carbon. The B-C bond is 0.5%, which is longer than the C-C bond, so the doping of boron atoms produces a certain chemical disorder, which changes the optical properties of the CDs and results in more phenomena and applications [23]. Therefore, boron dopants are a good choice for CDs. Currently boron-doped CDs have been extensively studied. In general, the raw material for synthesizing boron-doped CDs can be either single or multiple. Next, we introduce single boron doping CDs from both a single precursor and multiple precursors, starting from the raw materials for synthesizing boron-doped CDs.

2.1.1. Single precursorA single precursor containing both carbon and boron sources and using a single starting material to prepare boron-doped CDs can simplify the synthesis process while reducing byproducts. One of the most commonly used materials is phenylboronic acid, which is a very good carbon source because of its relatively high carbon content in the benzene ring. In addition, the benzene ring contains boronic acid groups, which can serve as a good boron source and retain boronic acid groups on the surface of the CDs, thus providing active sites and facilitating further detection applications. In 2014, using phenylboronic acid as the only precursor material, Xia et al. created boronic acid-modified CDs (C-dot) using a one-step hydrothermal technique. The CDs were directly functionalized by boronic acid during the synthesis process, and the boronic acid moiety provided the binding site for successful application in the determination of glucose in serum (Fig. S1A in Supporting information) [24]. In 2019, Cheng et al. prepared B-CDs using phenylboronic acid as a single precursor via hydrothermal method (Fig. S1B in Supporting information). The QY was 12% and it had excellent pH stability and water solubility. It was effective for the detection of sorbate and vitamin B12 [25].

In addition, studies on the preparation of boron-doped CDs with excellent properties using other single raw materials containing boron as the sole carbon source have been reported. In 2019, Sun et al. synthesized boric acid-modified CDs using 3-pyridineboronic acid as the only material by a one-step hydrothermal approach (Fig. S1C in Supporting information). The resultant CDs were successfully used in the detection of sialic acids by directly modifying boric acid without the introduction of additional binding sites [26]. In the same year, Li et al. fabricated B-CDs with green fluorescence emission by a one-pot solvothermal approach with polythiophene-3-boronic acid (PTB) as the sole precursor (Fig. S1D in Supporting information). The QY of B-CDs was 58.7%. Compared with CDs without boron doping, B-CDs had higher fluorescence intensity and showed an obvious emission redshift. The fluorescence and magnetic resonance (MR) dual modal properties of B-CDs made them potential markers for clinical applications [27].

2.1.2. Multiple precursorsAlthough the synthesis procedure can be simplified by employing a single precursor to create single boron-doped CDs, there are currently few pertinent studies. More preparation is performed using multiple precursor materials. By selecting suitable materials as carbon sources and mixing different materials containing boron atoms as boron dopants, boron-doped CDs with excellent properties were prepared. In the choice of boron sources, commonly used materials are boric acid [28-30], borax [31], and some other boron compounds [32,33]. In this section, different boron sources and different synthesis methods for single boron doping CDs were summarized in the Supporting information. Among them, the one-step synthesis of single boron-doped CDs using boric acid as a boron source includes hydrothermal [34-36], microwave [37,38], solvothermal [39,40], pyrolysis [41,42], and other methods [43-45]. One-step synthesis of single boron doping CDs using borax as a boron source can be done by constant potential electrolysis [31,46], hydrothermal [47], and microwave [48]. In addition, the one-step synthesis of single boron-doped CDs using other boron sources, and the multistep synthesis of single boron-doped CDs are also summarized [17,19,33,49-55].

2.2. Boron and other atom co-dopingTo date, single boron doping has shown good potential in improving the intrinsic properties of CDs, but there are certain limitations. For example, single boron doping CDs rarely exhibit long wavelength fluorescence, and most of the reported luminescence spectra of single boron doping CDs are limited to the blue-green range. However, many studies have shown that this drawback can be improved to some extent by doping with both boron and one or several other atoms [56-58]. Due to the synergistic effect between different atoms, co-doping of boron with other atoms can produce unique electronic structures and therefore has received much attention from researchers. At present, most reported studies are boron and nitrogen co-doping, and some studies of B, N, S, or B, N, F multiatom co-doping have been reported. We will discuss these in detail in this subsection.

2.2.1. Boron and nitrogen co-dopingThe synergistic effect between doped heteroatoms can create unique electronic structures. Boron and nitrogen are adjacent atoms of carbon with atomic sizes similar to that of carbon, which can produce uniform doping and uniform intrinsic defects. Doping boron and nitrogen in CDs can adjust the conduction/valence band positions of doped CDs by the synergistic effect of both, thus improving the conductivity and luminescence properties. In addition, additional boron doping leads to different conformations of carbon and nitrogen atoms as well as surface functional groups, which significantly improve the QY of B, N-CDs. B, N-CDs have received much research attention in recent years, and they may be synthesized from a variety of synthetic raw materials using both one-step and multistep synthesis methods, and they have shown excellent optical properties and great application potential. The research progress in the synthesis of B, N-CDs with a single precursor and multiple precursor materials is summarized in the Supporting information [59-68]. Among multiple precursor materials, we discuss the one-step synthesis of B, N-CDs using boric acid as a boron source and other boron sources [69-83], and the multistep synthesis of B, N-CDs [84-88].

2.2.2. Multiatom co-dopingHeteroatom doping of CDs is considered to be one of the most practical strategies for improving QY by increasing coordination sites and introducing more defects. Compared with single boron doping or boron and nitrogen co-doping, the abundant functional groups on the surface of CDs with three or even four co-doped atoms contain more excited states and may create more surface defects, which is beneficial to enhancing the performance. The co-doping process of boron and other multiple atoms is complicated, but many studies have reported mainly B, N, S co-doping [56,89-99], B, N, F [100,101], B, N, P three-atom doping [102], and B, N, P, S four-atom doping [103,104].

In the study of boron and multiple-atom co-doped CDs, B, N, and S co-doping is the most reported. A large number of studies have shown that the synergistic action of B, N and S atoms is conducive to improving the fluorescence properties of CDs and realizing long wavelength emission. In 2017, Ren et al. fabricated BNS-CDs using 4-aminobenzoborate hydrochloride as the boron source and 2,5-diaminobenzene sulfonic acid as the sulfur source (Fig. S14A in Supporting information). Due to the doping of B, N and S atoms and the introduction of more surface defects, the prepared BNS-CDs exhibited strong red fluorescence at approximately 600 nm [93]. Recently, Du et al. also prepared B, N, S-CDs with red emission from phenyl boric acid and 2,5-diaminobenzene sulfonic acid by a one-step hydrothermal carbonization approach, which had obvious pH-sensitive characteristics and could be used as a dual probe of PH and Ag+ biosensing (Fig. S14B in Supporting information) [90]. In addition to B, N, and S co-doping, other multiatom co-doping CDs, including B, N, and F co-doping, B, N, and P co-doping, and B, N, P, and S co-doping CDs, have also been studied. For example, in 2021, Zhu et al. synthesized N, B, F-CDs from 1-allyl-3-vinylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate ionic liquid and malonate by a hydrothermal approach, which showed excellent fluorescence stability and could be used for high sensitivity determination of sulfathiazole [100]. Meng et al. used diethylenetriamine, boric acid and phosphoric acid as nitrogen, boron and phosphorus sources to prepare carbonized polymer dots (CPDs) doped with N, P and B by a hydrothermal method. The prepared CPDs showed blue fluorescence and green room temperature phosphorescent emission, producing phosphorescence emission of different colors after annealing at different temperatures (Fig. S14C in Supporting information) [102]. In addition, Shafiei et al. first prepared N, S, P, B co-doped CDs from citric acid, ethylenediamine, phosphoric acid, L-cysteine, and boric acid. These CDs had been used to specifically detect methotrexate in plasma samples on-time [104]. From the available reports, we found that the co-doping of boron and multiple other heteroatoms is beneficial for achieving the long wavelength emission properties of CDs and is widely used in sensing fields.

Through the discussion above and Supporting information, we know that the doping strategies for boron-doped CDs mainly include single boron doping and co-doping of boron and other atoms. The precursor materials for single boron doping mainly consist of a single precursor and multiple precursors. The boron sources of multiple precursor materials are mainly boric acid, borax, and other boron-containing compounds, and the main synthetic methods are one-step synthesis, including hydrothermal, solvothermal, microwave, etc., as well as multistep synthesis. Co-doping of boron and other atoms is mainly done with boron and nitrogen co-doped. Depending on the precursor material, B, N-CDs can also be prepared from single and multiple materials. The most common boron source used for the preparation of B, N-CDs in multi-precursor systems is also boric acid, and the carbon and nitrogen sources can come from both natural biomass materials and chemical materials. In addition, boron sources such as borax, phenylboronic acid, and sodium borohydride can also be used for the preparation of B, N-CDs. Synthesis strategies include simple one-step synthesis and more complex two-step synthesis. Although the multistep synthesis procedure is more complicated, it can provide the direction choice of boron atom doping in the CDs and introduce boron atoms into the CDs more accurately. In addition, some researchers have also investigated the co-doping of boron with two or three other atoms. The boron-doped CDs prepared by different researchers through different doping strategies exhibit excellent fluorescence properties, opening up a broad prospect for the application of boron-doped CDs in different fields. In addition, during the preparation of boron-doped CDs, the doping amount of boron can be adjusted by changing the concentration of dopant and reaction conditions. Importantly, some characterization techniques, such as X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), can be used to analyse the presence, content and chemical state of boron doped into CDs to prove the doping state of boron.

3. Effect of boron doping on the performance of CDsBoron atoms have relatively low electronegativity and electron-absorbing effects. Thus, the introduction of individual boron into the CDs can change the properties of the CDs by forming some special chemical bonds or inducing more graphitization. Additionally, the synergistic effect of the two to create a special electronic structure can also have a substantial impact on the properties of CDs when nitrogen atoms with higher electronegativity and boron atoms with lower electronegativity are co-doped into CDs. This chapter will briefly describe the effects of boron doping on CDs in terms of fluorescence performance, phosphorescence performance, and catalytic performance.

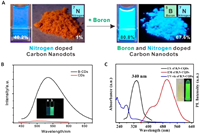

3.1. Effect on fluorescence performanceAccording to our understanding, the effect of boron doping on the fluorescence performance of CDs is mainly manifested in improving the QY or fluorescence intensity of CDs, promoting the redshift of emission wavelength and multiple emission. In 2016, Kim et al. synthesized boron and nitrogen doped carbon nanodots with significantly higher QY in solution and solid-state than nitrogen doped carbon nanodots (Fig. 1A). This is due to boron doping's ability to enable changes in C and N bonding topologies, which increases the ratio of graphite C to N and produces a uniformly distributed surface defect state, improving QY and significantly increasing fluorescence intensity [105]. B-CDs were prepared in the study of Li et al. and showed a 36-fold enhancement in fluorescence intensity compared to undoped CDs. In addition, they found that the emission wavelength of B-CDs was redshifted by approximately 38 nm compared to undoped CDs due to the effect of the introduction of boron atoms or boronic acid groups (Fig. 1B) [27]. Additionally, boron doping may impart multiple emission properties to CDs. In 2022, Fan et al. prepared B, N-CQDs by a micro-solvothermal approach. During the characterization of their optical properties, it was found that B, N-CQDs exhibited dual emission properties at 430 and 500 nm (Fig. 1C). This was explained by the doping of boron elements, which altered the CQDs' microstructure [106]. A large number of excellent reports have demonstrated that boron doping can significantly improve the fluorescence properties of CDs in different aspects.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (A) Comparation of nitrogen doped carbon nanodots and boron and nitrogen doped carbon nanodots. Reproduced with permission [105]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (B) Fluorescence spectra and images of (a) CDs prepared from polythiophene, and (b) B-CDs. Reproduced with permission [27]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier B.V. (C) Ultraviolet absorption, fluorescence excitation, and emission spectra of B, N-CQDs (the inset is a photo of CQDs solution under natural light (left) and 365 nm UV lamp (right)). Reproduced with permission [106]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier Ltd. | |

The phosphorescent properties of CDs have significant applications in the fields of information encryption and anti-counterfeiting, which have attracted much attention from researchers. The researchers discovered that boron doping can effectively reduce the energy gap between the single and triplet states of CDs and promote the phosphorescence emission of CDs. In addition, the covalent bond formed between CDs and boric acid during the heating process and the spatial restriction effect formed by boric acid around CDs can also promote the production of room temperature phosphorescence (RTP) in CDs [107,108]. In 2021, Tan et al. prepared a white emission material based on CDs (CD@BA) by using boric acid (BA), which showed fluorescence/phosphorescence dual emission. The CD@BA had a 30% QY of phosphorescence and a 13 s afterglow visible to the naked eye (Fig. 2A). The generation of phosphorescence emission was considerably aided by N and B co-doping and the potent contact between BA and CDs, which also prevented the solid from being quenched by aggregation [109]. Stimulus-responsive RTP of boron-doped CDs has attracted widespread attention. Recently, Xu et al. constructed a dynamic hydrogen bonding network based on BCQDs, which produced stimulus-responsive RTP in a paper after continuous stimulation with heat and water. The RTP was visible to the naked eye for approximately 11 s (Fig. 2B). Boron doping reduces the energy gaps of single and triplet states and can produce more triplet excitons from CQDs [110].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (A) (a) Schematic illustration of the preparation procedure and white-light emission processes for CD@BA powders. (Abs.: absorption; Fluo.: Fluorescence; Phos.: Phosphorescence). (b) Digital photographs of CD@BA powders before and after turning off 365 nm UV light. Reproduced with permission [109]. Copyright 2021, The Royal Society of Chemistry. (B) (a) Schematic representation of the overall fabrication process and the RTP sequential double-lock strategy generated by BCQDs for dynamic anti-counterfeiting. (b) Corresponding photographs of solid BCQDs and the BCQDs ethanol solution coated paper after being treated with cascade water and heating under daylight, excitation of 254 nm UV lamp and the cease of excitation. Reproduced with permission [110]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier Inc. | |

Replacing some carbon atoms in CDs with heteroatoms is an effective way to tune the electronic structure of CDs and improve catalytic performance. The researchers found that the electronegativity of boron is lower than that of carbon, and the electronegativity of nitrogen is higher than that of carbon. The synergistic coupling effect of boron and nitrogen co-doping creates a unique electronic structure for CDs, which improves their catalytic performance. Therefore, boron and nitrogen co-doping CDs are a promising alternative to metal-based catalysts. In 2016, Nabid et al. synthesized B, N-CDs which were analyzed and found to exhibit excellent catalytic activity based on the synergistic coupling effect between B, N, and C heteroatoms, and the catalysts could be utilized for the catalysis of hydrogen production from NaBH4 hydrolysis [111]. In 2021, Lu et al. synthesized B, N-CDs, which can be used as efficient oxygen reduction catalysts when loaded onto multiwalled carbon nanotubes. This is because nitrogen doping can alter carbon atoms' electron distribution and make them the active center. Meanwhile, boron doping is beneficial for adsorbing intermediates and oxygen [112]. In addition, Yeh et al. prepared metal-free BGQDs/NCNTs, which also exhibited excellent oxygen reduction reaction electrocatalytic activity because of abundant active sites and synergistic effects and might become a novel low-cost and efficient electrocatalyst [113].

During the study of boron-doped CDs, in addition to fluorescence, phosphorescence and catalytic performances, researchers found that the doping of boron atoms also has an effect on the electrochemiluminescence of CDs, enhancing the electrical conductivity as well as the intensity of electrochemiluminescence [114-116]. It also improves the fluorescence lifetime [117], affects the magnetic properties [118], and enhances the nonlinear response of CDs [12]. The effect of boron doping on different features of CDs can result in increased performance of CDs, hence broadening the applications of boron-doped CDs in sensing, anti-counterfeiting, and catalysis.

4. ApplicationBoron-doped CDs exhibit outstanding fluorescence and phosphorescence performances, as well as great fluorescence stability, making them interesting for use in a variety of applications. We will briefly introduce the applications of boron-doped CDs in the fields of optical sensors and anti-counterfeiting in this review.

4.1. Optical sensorsBoron-doped CDs exhibit excellent fluorescence properties and have a wide range of applications in optical sensors. In particular, they can be used as novel fluorescent probes for metal ion detection and glucose sensing. It has been shown that boron doping can effectively improve the sensing and detection capabilities of CDs as optical sensors [26,89,91]. In 2014, Qiu et al. prepared BGQDs for the first time and found that the presence of boronic acid groups on the surface of the prepared BGQDs could enable the use of BGQDs as novel fluorescent probes for glucose sensing. The sensing mechanism is due to the fact that two boronic acid groups on the surface of BGQDs react with two cis-diol units of glucose to form structurally rigid aggregates, which restrict intramolecular rotation, leading to fluorescence enhancement (Fig. S15A in Supporting information) [55]. In 2018, Li et al. fabricated boronic acid-functionalized CDs. A sensor for glucose detection was constructed based on the assembly into a coordination compound of boronic acid groups on the surface of the CDs and glucose cis-diol groups, leading to fluorescence quenching of the aggregated state on the CDs (Fig. S15B in Supporting information) [50]. In 2019, Yuan et al. constructed a fluorescence sensor based on B, N-GQDs. Due to boron and nitrogen co-doping, the "off-on" fluorescence detection of F− and Hg2+ was successfully achieved [119]. In 2022, Sun et al. fabricated NB-CDs with orange fluorescence, which could be used as an innovative fluorescent probe for the ratiometric sensing of Al3+ and fluorogenic detection of Ce4+ (Fig. S15C in Supporting information). After comparative experiments, it was shown that boron doping could improve the detection sensitivity and range for Ce4+. This might be because boron doping makes it easier for hydrogen bonds to form, which is better for the use of metal ion detection [120]. A large number of studies have shown that boron-doped CDs have excellent fluorescence properties and potential applications in the field of optical sensors.

4.2. Information encryption and anti-counterfeitingWith unique properties such as excellent fluorescence stability, multiple emission and long-life phosphorescence emission, boron-doped CDs show great potential in the field of information encryption and anti-counterfeiting. In 2022, Shen et al. fabricated multi-emission NB-CDs, which had excellent stability and were used to achieve multilevel anti-counterfeit printing. Aqueous solutions of NB-CDs had a long-term stability of more than two months and thermal stability at a temperature of 300 ℃, meeting the requirements of fluorescent inks used for anti-counterfeit printing. The NB-CDs were used as fluorescent inks for printing out digital codes and 2D codes on banknotes, showing purple, blue, and green fluorescence after excitation at 300, 330, and 490 nm, respectively (Fig. S16A in Supporting information). The tunable multicolor emission of NB-CDs achieved a more advanced application of multi-color optical anti-counterfeits [85]. Additionally, boron atoms can decrease the energy gap between the single and triplet states of CDs and increase the rate of intersystem crossing, making boron-doped CDs more advanced for information encryption and anti-counterfeiting applications due to their long lifetime and multicolor phosphorescence performance. Meng et al. prepared boron-doped multicolor CPDs with thermal stimulation response, which displayed yellow-green RTP at 200 ℃, yellow RTP at 260 ℃ and orange-red RTP at 280 ℃. Based on different RTP colors at different temperatures and excellent light stability, CPDs successfully achieved advanced anti-counterfeiting for writable and printable security inks (Fig. S16B in Supporting information) [102]. In 2022, Li et al. created boron-doped RTP CDs that had a strong green afterglow that could be seen with the naked eye for 7 s and were effective for information protection and anti-counterfeit applications [51]. Many studies have demonstrated the potential application of boron-doped CDs in the fields of information encryption and anti-counterfeiting.

Based on the above discussion, we know from many studies that boron-doped CDs can be used as fluorescent probes with potential applications in the field of optical sensors. They can also be used as fluorescent inks for information encryption and anti-counterfeiting applications. Additionally, some researchers have also found potential applications for boron-doped CDs in optoelectronic devices [39,121], catalysts [54], and bioimaging [122].

5. Summary and prospectsIn this review, we introduce the doping strategies of boron-doped CDs, the effect of boron doping on the performance of CDs and the applications of boron-doped CDs. We focus on single boron doping and boron and other atom co-doping (mainly boron and nitrogen co-doping), from different precursor materials (including a single precursor, multiple precursors and different boron doping sources) to different synthesis methods and introduce the doping strategies of boron-doped CDs in detail. Then, the effects of boron doping on the fluorescence, phosphorescent and catalytic performances of CDs are analysed. Finally, the applications of boron-doped CDs in optical sensors, information encryption and anti-counterfeiting are briefly introduced. Boron doping can adjust the electronic structure of CDs, generate p-type carriers, reduce the energy gap between the singlet and triplet states and promote intersystem crossing. It is an effective method to improve the fluorescence, phosphorescence and catalytic properties of CDs.

Although boron-doped CDs have been widely studied, they still face some challenges. For example, at present, the synthesis of CDs from biomass has been widely reported [123], but there are very few studies on boron-doped CDs synthesized from single biomass materials. Most studies use chemical substances as boron doping sources, which have a certain toxicity. At present, the preparation of boron-doped CDs and synthesis strategies are mainly hydrothermal or solvothermal, which takes a long time and uses an autoclave, which has certain safety risks. Although boron doping significantly improves the fluorescence intensity of CDs, the emission wavelength is usually shorter when the fluorescence intensity is higher. Additionally, the luminescence mechanism of boron-doped CDs is still unclear and is limited to surface states, carbon nuclei and quantum size effects. Therefore, in follow-up research, we can focus on the following. First, we can find suitable boron-rich biomass materials to synthesize boron-doped CDs with excellent properties. Second, the microwave method can be used to replace the hydrothermal or solvothermal method, which is time-consuming and safe. In addition, it is necessary to explore new synthesis methods to prepare boron-doped CDs. Third, through the selection of suitable raw materials or methods, the surface structure of the boron-doped CDs is changed, while improving fluorescence intensity and emission wavelengths, thereby preparing high QY boron-doped CDs with long wavelength emissions. In addition, full-color emissive CDs can be effectively used in the field of biological and optoelectronic devices because of their color-tunable properties [124], so it is necessary to prepare full-color emissive boron-doped CDs with suitable materials and methods. Finally, we need to further explore the luminescence mechanism of boron-doped CDs with characterization tools. It is also necessary to further develop high-resolution characterization techniques to accurately obtain and quantify the structure, composition and properties of boron-doped CDs. We believe that with the continuous deepening and optimization of research, the performances of boron-doped CDs will be better improved and enhanced, and they will have more potential applications.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsWe gratefully acknowledge the Youth Talent Program Startup Foundation of Qufu Normal University (No. 602601) and the Natural Science Foundation of Rizhao (No. RZ2021ZR37).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109136.

| [1] |

X. Xu, R. Ray, Y. Gu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126 (2004) 12736-12737. DOI:10.1021/ja040082h |

| [2] |

B.B. Chen, M.L. Liu, C.M. Li, C.Z. Huang, Adv. Colloid Interf. Sci. 270 (2019) 165-190. DOI:10.1016/j.cis.2019.06.008 |

| [3] |

Y. Liu, L. Zhou, Y. Li, R. Deng, H. Zhang, Nanoscale 9 (2017) 491-496. DOI:10.1039/C6NR07123F |

| [4] |

S. Miao, K. Liang, J. Zhu, et al., Nano Today 33 (2020) 100879. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2020.100879 |

| [5] |

S.J. Park, J.Y. Park, J.W. Chung, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 383 (2020) 123200. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123200 |

| [6] |

H. Tao, K. Yang, Z. Ma, et al., Small 8 (2012) 281-290. DOI:10.1002/smll.201101706 |

| [7] |

Q. Liu, S. Xu, C. Niu, et al., Biosens. Bioelectron. 64 (2015) 119-125. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2014.08.052 |

| [8] |

Y. Liu, J. Chen, Z. Xu, et al., Environ. Chem. Lett. 20 (2022) 3415-3420. DOI:10.1007/s10311-022-01475-0 |

| [9] |

S. Ren, B. Liu, M. Wang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 10 (2022) 11338-11346. DOI:10.1039/D2TC02664C |

| [10] |

B. Wang, G.I.N. Waterhouse, S. Lu, Trends Chem. 5 (2023) 76-87. DOI:10.1016/j.trechm.2022.10.005 |

| [11] |

S. Zhu, J. Zhang, S. Tang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 22 (2012) 4732-4740. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201201499 |

| [12] |

A.B. Bourlinos, G. Trivizas, M.A. Karakassides, et al., Carbon 83 (2015) 173-179. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2014.11.032 |

| [13] |

K. Jiang, S. Sun, L. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 5360-5363. DOI:10.1002/anie.201501193 |

| [14] |

X. Li, M. Zheng, H. Wang, et al., J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 609 (2022) 54-64. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.11.179 |

| [15] |

Y. Li, H. Lin, C. Luo, et al., RSC Adv. 7 (2017) 32225-32228. DOI:10.1039/C7RA04781A |

| [16] |

X. Zhang, Y. Ren, Z. Ji, J. Fan, J. Mol. Liquids 311 (2020) 113278. DOI:10.1016/j.molliq.2020.113278 |

| [17] |

Y. Ma, A.Y. Chen, Y.Y. Huang, et al., Carbon 162 (2020) 234-244. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.02.048 |

| [18] |

K. Yuan, X. Zhang, X. Li, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 397 (2020) 125487. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125487 |

| [19] |

X. Shan, L. Chai, J. Ma, et al., Analyst 139 (2014) 2322-2325. DOI:10.1039/C3AN02222F |

| [20] |

C. Shen, J. Wang, Y. Cao, Y. Lu, J. Mater. Chem. C 3 (2015) 6668-6675. DOI:10.1039/C5TC01156F |

| [21] |

S. Kim, B.K. Yoo, Y. Choi, B.S. Kim, O.H. Kwon, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 20 (2018) 11673-11681. DOI:10.1039/C8CP01619D |

| [22] |

S.V. Carneiro, J.J.P. Oliveira, V.S.F. Rodrigues, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14 (2022) 43597-43611. DOI:10.1021/acsami.2c09197 |

| [23] |

J. Zhou, H. Zhou, J. Tang, et al., Microchim. Acta 184 (2016) 343-368. |

| [24] |

P. Shen, Y. Xia, Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 5323-5329. DOI:10.1021/ac5001338 |

| [25] |

Y. Jia, Y. Hu, Y. Li, et al., Microchim. Acta 186 (2019) 84. DOI:10.1007/s00604-018-3196-5 |

| [26] |

S. Xu, S. Che, P. Ma, et al., Talanta 197 (2019) 548-552. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2019.01.074 |

| [27] |

X. Zhao, L. Dong, Y. Ming, et al., Talanta 200 (2019) 9-14. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2019.03.022 |

| [28] |

L. Largitte, N.A. Travlou, M. Florent, J. Secor, T.J. Bandosz, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 405 (2021) 112903. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112903 |

| [29] |

F. Wang, Q. Hao, Y. Zhang, Y. Xu, W. Lei, Microchim. Acta 183 (2015) 273-279. |

| [30] |

Z.X. Wang, X.H. Yu, F. Li, et al., Microchim. Acta 184 (2017) 4775-4783. DOI:10.1007/s00604-017-2526-3 |

| [31] |

Z. Fan, Y. Li, X. Li, et al., Carbon 70 (2014) 149-156. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2013.12.085 |

| [32] |

M. Li, X. Li, M. Jiang, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 399 (2020) 125741. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125741 |

| [33] |

Z. Peng, Y. Zhou, C. Ji, et al., Nanomaterials 10 (2020) 1560. DOI:10.3390/nano10081560 |

| [34] |

T. Van Tam, S.G. Kang, K.F. Babu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 5 (2017) 10537-10543. DOI:10.1039/C7TA01485F |

| [35] |

J. Vinoth Kumar, V. Arul, R. Arulmozhi, N. Abirami, New J. Chem. 46 (2022) 7464-7476. DOI:10.1039/D2NJ00786J |

| [36] |

A. Wibrianto, D.F. Putri, S.C.W. Sakti, H.V. Lee, M.Z. Fahmi, RSC Adv. 11 (2021) 37375-37382. DOI:10.1039/D1RA06148H |

| [37] |

R. Liang, L. Huo, A. Yu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 243-246. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.05.046 |

| [38] |

A. Wibrianto, S.Q. Khairunisa, S.C.W. Sakti, et al., RSC Adv. 11 (2020) 1098-1108. |

| [39] |

K.B. Cai, H.Y. Huang, M.L. Hsieh, et al., ACS Nano 16 (2022) 3994-4003. DOI:10.1021/acsnano.1c09582 |

| [40] |

S. Mandal, J. Pal, R. Subramanian, P. Das, Nano Res. 13 (2020) 2770-2776. DOI:10.1007/s12274-020-2927-1 |

| [41] |

Y. Ding, X. Wang, M. Tang, H. Qiu, Adv. Sci. 9 (2022) e2103833. DOI:10.1002/advs.202103833 |

| [42] |

Q. Feng, Z. Xie, M. Zheng, Chem. Eng. J. 420 (2021) 127647. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.127647 |

| [43] |

S. Cui, B. Wang, Y. Zan, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 431 (2022) 133373. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.133373 |

| [44] |

T. Li, C. Wu, M. Yang, et al., Langmuir 38 (2022) 2287-2293. DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.1c02973 |

| [45] |

X. Niu, T. Song, H. Xiong, Chin. Chem. Lett. 32 (2021) 1953-1956. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.01.006 |

| [46] |

L. Ji, L. Chen, P. Wu, D.F. Gervasio, C. Cai, Anal. Chem. 88 (2016) 3935-3944. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b00131 |

| [47] |

A. Meng, Y. Zhang, X. Wang, et al., Colloids Surfaces A: Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 648 (2022) 129150. DOI:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129150 |

| [48] |

X. Hai, Q.X. Mao, W.J. Wang, et al., J. Mater. Chem. B 3 (2015) 9109-9114. DOI:10.1039/C5TB01954K |

| [49] |

H.K. Sadhanala, S. Pagidi, A. Gedanken, J. Mater. Chem. C 9 (2021) 1632-1640. DOI:10.1039/D0TC05081D |

| [50] |

W.S. Zou, C.H. Ye, Y.Q. Wang, W.H. Li, X.H. Huang, Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 271 (2018) 54-63. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2018.05.115 |

| [51] |

M. Cheng, L. Cao, H. Guo, W. Dong, L. Li, Sensors 22 (2022) 2944. DOI:10.3390/s22082944 |

| [52] |

W. Li, W. Zhou, Z. Zhou, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 7278-7283. DOI:10.1002/anie.201814629 |

| [53] |

J. Shi, Y. Zhou, J. Ning, et al., Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 281 (2022) 121597. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2022.121597 |

| [54] |

Y. Yue, B. Wang, S. Wang, et al., Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 5174-5177. DOI:10.1039/C9CC09701E |

| [55] |

L. Zhang, Z.Y. Zhang, R.P. Liang, Y.H. Li, J.D. Qiu, Anal. Chem. 86 (2014) 4423-4430. DOI:10.1021/ac500289c |

| [56] |

S. Huang, E. Yang, J. Yao, Y. Liu, Q. Xiao, Anal. Chim. Acta 1035 (2018) 192-202. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2018.06.051 |

| [57] |

L.F. Pang, H. Wu, M.J. Fu, X.F. Guo, H. Wang, Microchim. Acta 186 (2019) 708. DOI:10.1007/s00604-019-3852-4 |

| [58] |

C. She, Z. Wang, J. Zeng, F.G. Wu, Carbon 191 (2022) 636-645. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2022.02.005 |

| [59] |

Q. Cheng, Y. He, Y. Ge, G. Song, Micro Nano Lett. 13 (2018) 1175-1178. DOI:10.1049/mnl.2017.0779 |

| [60] |

Y. Hu, R. Guan, X. Shao, et al., J. Fluoresc. 30 (2020) 1447-1456. DOI:10.1007/s10895-020-02592-1 |

| [61] |

M. Jia, L. Peng, M. Yang, et al., Carbon 182 (2021) 42-50. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2021.05.050 |

| [62] |

M. Mao, T. Tian, Y. He, et al., Microchim. Acta 185 (2017) 17. |

| [63] |

P. Ni, J. Xie, C. Chen, Y. Jiang, Y. Lu, X. Hu, Microchim. Acta 186 (2019) 202. DOI:10.1007/s00604-019-3303-2 |

| [64] |

L. Peng, M. Yang, M. Zhang, M. Jia, Food Chem. 392 (2022) 133265. DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.133265 |

| [65] |

Y.R. Wang, X. Chen, Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 1119-1124. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.12.009 |

| [66] |

T. Tian, Y. He, Y. Ge, G. Song, Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 240 (2017) 1265-1271. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2016.09.114 |

| [67] |

N. Xiao, S.G. Liu, S. Mo, et al., Talanta 184 (2018) 184-192. DOI:10.1016/j.talanta.2018.02.114 |

| [68] |

N. Xiao, S.G. Liu, S. Mo, et al., Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 273 (2018) 1735-1743. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2018.07.097 |

| [69] |

V. Arul, P. Chandrasekaran, G. Sivaraman, M.G. Sethuraman, Diamond Rel. Mater. 116 (2021) 108437. DOI:10.1016/j.diamond.2021.108437 |

| [70] |

Q. Fu, C. Long, J. Huang, et al., J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 9 (2021) 106882. DOI:10.1016/j.jece.2021.106882 |

| [71] |

H.L. Tran, W. Darmanto, R.A. Doong, Nanomaterials 10 (2020) 1883. DOI:10.3390/nano10091883 |

| [72] |

J. Xu, Y. Guo, L. Qin, et al., Ceramics Int. 49 (2023) 7546-7555. DOI:10.1016/j.ceramint.2022.10.253 |

| [73] |

Z. Liu, Z. Mo, N. Liu, et al., J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 389 (2020) 112255. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2019.112255 |

| [74] |

Y. Ma, Z. Ma, X. Huo, et al., J. Agric. Food. Chem. 68 (2020) 10223-10231. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c04251 |

| [75] |

F. Pschunder, M.A. Huergo, J.M. Ramallo-López, et al., J. Phys. Chem. C 124 (2019) 1121-1128. |

| [76] |

R. Shokri, M. Amjadi, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 425 (2022) 113694. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2021.113694 |

| [77] |

B. Tian, T. Fu, Y. Wan, et al., J. Nanobiotechnol. 19 (2021) 456. DOI:10.1186/s12951-021-01211-w |

| [78] |

Y. Wei, L. Chen, J. Wang, et al., Opt. Mater. 100 (2020) 109647. DOI:10.1016/j.optmat.2019.109647 |

| [79] |

J. Xu, Y. Guo, T. Gong, et al., Inorg. Chem. Commun. 145 (2022) 110047. DOI:10.1016/j.inoche.2022.110047 |

| [80] |

Y. Guo, Y. Chen, F. Cao, et al., RSC Adv. 7 (2017) 48386-48393. DOI:10.1039/C7RA09785A |

| [81] |

Y. Liu, W. Li, P. Wu, et al., Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 281 (2019) 34-43. DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2018.10.075 |

| [82] |

Y. Wang, X. Hu, W. Li, et al., Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 243 (2020) 118807. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2020.118807 |

| [83] |

Z. Yan, W. Yao, K. Mai, et al., RSC Adv. 12 (2022) 8202-8210. DOI:10.1039/D1RA08219A |

| [84] |

S. Dey, A. Govindaraj, K. Biswas, C.N.R. Rao, Chem. Phys. Lett. 595- 596 (2014) 203-208. |

| [85] |

X. Gu, L. Zhu, D. Shen, C. Li, Polymers 14 (2022) 2779. DOI:10.3390/polym14142779 |

| [86] |

W. Jiang, L. Liu, Y. Wu, et al., Nanoscale Adv. 3 (2021) 4536-4540. DOI:10.1039/D1NA00252J |

| [87] |

H. Wang, Q. Mu, K. Wang, et al., Appl. Mater. Today 14 (2019) 108-117. DOI:10.1016/j.apmt.2018.11.011 |

| [88] |

L. Zhu, D. Shen, K.Hong Luo, J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 617 (2022) 557-567. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2022.03.039 |

| [89] |

R.K. Das, S. Mohapatra, J. Mater. Chem. B 5 (2017) 2190-2197. DOI:10.1039/C6TB03141B |

| [90] |

J. Du, N. Xu, C. Wang, et al., J. Mater. Sci. 57 (2022) 21693-21708. DOI:10.1007/s10853-022-07988-x |

| [91] |

Y. Huang, Z. Cheng, Nano 12 (2017) 1750123. DOI:10.1142/S1793292017501235 |

| [92] |

W.K. Li, J.T. Feng, Z.Q. Ma, Carbon 161 (2020) 685-693. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.01.098 |

| [93] |

Y. Liu, W. Duan, W. Song, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9 (2017) 12663-12672. DOI:10.1021/acsami.6b15746 |

| [94] |

Y. Liu, Z. Wei, W. Duan, et al., Dyes Pigm. 149 (2018) 491-497. DOI:10.1016/j.dyepig.2017.10.039 |

| [95] |

M. Masteri Farahani, F. Ghorbani, N. Mosleh, Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 245 (2021) 118892. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2020.118892 |

| [96] |

S. Mohapatra, R.K. Das, Anal. Chim. Acta 1058 (2019) 146-154. DOI:10.1016/j.aca.2019.01.021 |

| [97] |

B. Peng, J. Xu, M. Fan, et al., Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 412 (2020) 861-870. DOI:10.1007/s00216-019-02284-1 |

| [98] |

S. Song, J. Hu, M. Li, et al., Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 118 (2021) 111478. DOI:10.1016/j.msec.2020.111478 |

| [99] |

C. Yin, M. Wu, T. Liu, et al., Microchem. J. 178 (2022) 107405. DOI:10.1016/j.microc.2022.107405 |

| [100] |

L. Chen, Y. Liu, G. Cheng, et al., Sci. Total Environ. 759 (2021) 143432. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143432 |

| [101] |

P. Tiwari, N. Kaur, V. Sharma, S.M. Mobin, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A: Chem. 403 (2020) 112847. DOI:10.1016/j.jphotochem.2020.112847 |

| [102] |

Z. Wang, J. Shen, B. Xu, et al., Adv. Opt. Mater. 9 (2021) 2100421. DOI:10.1002/adom.202100421 |

| [103] |

C. Karami, M.A. Taher, M. Shahlaei, J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 31 (2020) 5975-5983. DOI:10.1007/s10854-020-03157-5 |

| [104] |

M. Molaparast, P. Eslampour, J. Soleymani, V. Shafiei Irannejad, Iran. J. Pharm. Res. 21 (2022) e126918. |

| [105] |

Y. Choi, B. Kang, J. Lee, Chem. Mater. 28 (2016) 6840-6847. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01710 |

| [106] |

C. Wang, Q. Sun, C. Li, et al., Mater. Res. Bull. 155 (2022) 111970. DOI:10.1016/j.materresbull.2022.111970 |

| [107] |

Q. Cheng, Z. Chen, L. Hu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 108070. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.108070 |

| [108] |

Y. Li, Q. Li, S. Meng, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107794. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107794 |

| [109] |

Q. Li, Y. Li, S. Meng, et al., J. Mater. Chem. C 9 (2021) 6796-6801. DOI:10.1039/D1TC01001H |

| [110] |

L. Yang, Q. Zhang, Y. Huang, et al., J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 632 (2023) 129-139. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2022.11.062 |

| [111] |

M.R. Nabid, Y. Bide, N. Fereidouni, New J. Chem. 40 (2016) 8823-8828. DOI:10.1039/C6NJ01650B |

| [112] |

Y. Pei, H. Song, Y. Liu, et al., J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 600 (2021) 865-871. DOI:10.1016/j.jcis.2021.05.089 |

| [113] |

Y.X. Wang, M. Rinawati, W.H. Huang, et al., Carbon 186 (2022) 406-415. DOI:10.1016/j.carbon.2021.10.027 |

| [114] |

Y.Z. Guo, J.L. Liu, Y.F. Chen, et al., Anal. Chem. 94 (2022) 7601-7608. DOI:10.1021/acs.analchem.2c00763 |

| [115] |

K.H. Kim, H.J. Ahn, Int. J. Energy Res. 46 (2022) 8367-8375. DOI:10.1002/er.7738 |

| [116] |

T. Zhang, D. Long, X. Gu, M. Yang, Microchim. Acta 189 (2022) 389. DOI:10.1007/s00604-022-05483-3 |

| [117] |

S. Ghosh, A. Ghosh, G. Ghosh, K. Marjit, A. Patra, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 12 (2021) 8080-8087. DOI:10.1021/acs.jpclett.1c02116 |

| [118] |

H. Wang, R. Revia, K. Wang, et al., Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1605416. DOI:10.1002/adma.201605416 |

| [119] |

P. Yang, J. Su, R. Guo, F. Yao, C. Yuan, Analyt. Methods 11 (2019) 1879-1883. DOI:10.1039/C9AY00249A |

| [120] |

X. Li, L. Zhao, Y. Wu, et al., Spectrochim. Acta A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 282 (2022) 121638. DOI:10.1016/j.saa.2022.121638 |

| [121] |

H. Wang, Z. Zhang, Q. Yan, ChemistrySelect 5 (2020) 13969-13973. DOI:10.1002/slct.202004009 |

| [122] |

S.N. Karadag, O. Ustun, A. Yilmaz, M. Yilmaz, Chem. Phys. 562 (2022) 111678. DOI:10.1016/j.chemphys.2022.111678 |

| [123] |

M. Fang, B. Wang, X. Qu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 35 (2024) 108423. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108423 |

| [124] |

X. Yang, X. Li, B. Wang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 613-625. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.08.077 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35