b Jiangsu Co-Innovation Center of Efficient Processing and Utilization of Forest Resources, International Innovation Center for Forest Chemicals and Materials, College of Chemical Engineering, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing 210037, China;

c State Key Laboratory of Organometallic Chemistry, Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai 200032, China

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a widely recognized greenhouse gas that has significant implications for global climate change and the environment due to its continuous release from the extensive use of fossil fuels. To address this issue, the capture and utilization of excessive CO2, as a cheap, abundant, and renewable C1 source has gained considerable attention in recent years. This emerging strategy to convert CO2 into valuable fine and bulky chemicals, including methanol, formic acid, methane, carbonates, amides, and carboxylic acids [1-5]. Despite its potential, the current utilization of CO2 remains limited. Given the approximate global emission of 30Gt CO2 per year, only a small amount of it is currently utilized and transformed into urea (200 Mt/year) [6]. Hence, there is a pressing need to develop efficient and novel approaches for its valorization, possessing significant challenges in the current stage.

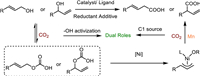

Carboxylic acids play a vital role in various industries such as cosmetics, plastics, dyes, pesticides, and pharmaceuticals due to their diverse applications [7-9]. Conventional methods for their synthesis, as shown in Fig. 1a, typically involve oxidation reactions. In contrast, the transition metal-catalyzed carboxylation of nucleophilic reagents with CO2 offers an alternative approach to obtain C1-elongated carboxylic acids. This method offers several advantages, including the avoidance of excessive use of oxidizing agents and the consequent generation of pollutants. Moreover, it enables the convenient synthesis of a diverse library of products [10].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Carboxylic acids synthesis. (a) Traditional methods for carboxylic acids synthesis. (b) Carboxylation reactions of olefins, esters and organic halides with CO2. (c) Carboxylation reactions of alcohols with CO2. | |

In contrast to the extensively studied transition metal-catalyzed carboxylation of active olefins [11-14], organic halides [15], and esters [16,17], which are typically derived from alcohols (Fig. 1b), the direct carboxylation of alcohols with CO2 represents a straightforward and more sustainable approach. This method constitutes particularly attractive when utilizing abundant and cost-effective bio-alcohols. For instance, propylene, which costs approximately 2.48 $/kg, and glycerin, which costs only 0.435 $/kg, can serve as readily available starting materials [18-20].

However, the exploration of direct carboxylation of alcohols with CO2 is still in its early stage, primarily due to several challenges. Firstly, the activation energy of CO2 is relatively high, with strong O═C═O bonds (C═O bond strength of 532 kJ/mol) [21]. This poses a significant hurdle for efficient CO2 activation. Secondly, the dissociation energy of the C—O bond in alcohols is also high, and hydroxide (—OH) functions as a poor leaving group [22,23]. Additionally, the presence of unprotected —OH groups in alcohols makes them highly reactive [24], leading to the formation of various side products through etherification, elimination, or substitution reactions. Therefore, the development of suitable strategies that can selectively activate the C—O bond and enable efficient carbonyl insertion is essential for the direct synthesis of carboxylic acids from alcohols.

Currently, three main strategies have been identified to address the challenges associated with the carboxylation of alcohols with CO2, taking into account the unique activation requirements of different alcohols. These strategies include: (a) in-situ esterification, (b) in-situ halogenation, and (c) photocatalysis (Fig. 1c). In this perspective, we discuss recent advancements in the carboxylation of alcohols with CO2 mainly based on these activation strategies. Furthermore, we provide an outlook on potential future trends in this field.

2. In-situ esterification strategyEsters are widely recognized as one kind of good leaving groups compared to hydroxyl (—OH) groups, and they have been extensively used in organic synthesis [25]. Martin and coworkers have developed several methods for the carboxylation of alcohol esters with CO2 using Ni or Co catalysts in the presence of appropriate reductants [16,17]. Both acetates and pivalates were successfully converted into the desired carboxylic acids (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, Martin and Mei achieved the direct synthesis of carboxylic acids from allylic alcohols via regioselective catalytic carboxylation without the need to pre-synthesize alcohol esters (Fig. 2) [26-29]. In this process, CO2 not only acts as the C1 source, but also activates the —OH group through the formation of a hydrogen carbonate intermediate [28]. This activation occurs through a "proton-relay" process facilitated by hydrogen bonding interactions between the alcohols and residual moisture. These interactions promote Ni-catalyzed C—O bond cleavage, which is the rate-determining step [29]. The use of specific ligands allows for precise modulation of the regiodivergence of the reactions, leading to the selective production of α-branched or linear carboxylic acids. However, it should be noted that these newly developed protocols are only applicable to allylic and propargylic alcohols and require a large excess of metallic (Zn, Mn) reductants.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. Carboxylation of allylic and propargylic alcohols with CO2 using the in-situ esterification strategy. | |

The carboxylation of simple small-molecule alcohols, such as methanol and cyclohexanol, poses a significant challenge and has been identified as one of bottlenecks in expanding the industrial application of CO2 utilization. To address this challenge, Han and colleagues developed an in-situ halogenation strategy that effectively activates alcohols, resulting in the successful synthesis of valuable carboxylic acids [4]. This transformation involves the use of lithium halides to facilitate the in-situ halogenation process, known as hydrocarboxylation, which can be applied not only to methanol but also to other higher alcohols.

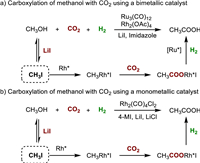

In 2016, Han's group achieved a significant milestone by successfully conducting the hydrocarboxylation of methanol with CO2 and H2 using a Ru-Rh bimetallic catalyst, which selectively produced acetic acid (Fig. 3a) [30]. The process involved several key steps. Initially, methanol underwent in-situ conversion into CH3I in the presence of LiI. The resulting CH3I then underwent oxidative addition with an active Rh species (RhL), forming CH3-RhL-I. Subsequent insertion of CO2 into the CH3-Rh bond yielded the intermediate CH3COO-RhL-I. Through reductive elimination in the presence of H2, the active Ru-L species facilitated the production of acetic acid. LiI was identified as the optimal promoter for this transformation due to its strong Lewis acidity, appropriate Li-ion size, and the high nucleophilicity of the iodide anion. Additionally, imidazole was found to influence the selectivity by facilitating CO2 insertion while inhibiting CO formation.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. Carboxylation reactions of methanol with CO2 and H2 using the in-situ halogenation strategy. | |

Subsequently, the same group discovered a more efficient catalytic system by utilizing a monometallic catalyst Rh2(CO)4Cl2 in the presence of 4-methylimidazole (4-MI), LiCl, and LiI (Fig. 3b) [31]. This new catalytic system exhibited significantly improved turnover frequency (TOF) and yield compared to the previous one (26.2 h−1 and 81.8% vs. 10.1 h −1 and 23.2%) at 180 ℃. Control experiments confirmed that the reaction proceeded via direct CO2 insertion rather than the CO pathway. The addition of LiCl not only enhanced the catalytic activity and stability of the catalyst but also reduced the amount of corrosive LiI, making it more suitable for potential industrial applications.

Besides the synthesis of acetic acid, Han, Qian, and other colleagues have recently introduced two additional catalytic protocols for the hydrocarboxylation of alcohols with CO2 and H2 to produce higher carboxylic acids (Fig. 4). Building upon their previous monometallic system [32], they combined a Rh catalyst with I2 in an ionic liquid-water mixture (1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium iodide, Fig. 4a) [33]. At 170 ℃, they successfully converted various polyols including glycerol, erythritol, xylitol, and mannitol into C1-elongated carboxylic acids with reasonable yields. Even crude glycerol, a major by-product of the biodiesel industry [34], was compatible with the system, although the yield was slightly lower compared to pure glycerol (76.5% vs. 86.4%).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Carboxylation reactions of alcohols with CO2 and H2 using the in-situ halogenation strategy. | |

The second protocol involved the use of iridium(III)acetate with LiI as the promoter in acetic acid (Fig. 4b) [35]. Under the optimized reaction conditions, primary, secondary, and tertiary alcohols as well as polyols were well compatible, leading to the formation of various higher carboxylic acids with yields ranging from 7.7% to 59.6%. Very recently, they further successfully extended this strategy to saccharides, including glucose, xylose, fructose, and other analogues [36]. Moderate to good yields of desired carboxylic acids were attained (up to 72%, Fig. 4c). Intermediates including CO, 2,5-dimethyltetrahydrofuran, ketones, olefins, alcohols, and corresponding acetates were found during the reaction process. These outcomes establish a solid research foundation for valorization of both CO2 and biomass.

Based on systematic control experiments, similar mechanisms were proposed for both reactions. Initially, the reverse water-gas shift process converted CO2 and H2 into CO and water. Simultaneously, the alcohol substrates underwent conversion into olefin and/or alkyl iodide intermediates, which served as potential alkyl reagents. The alkyl groups then underwent oxidative addition with an active metal species (M = Ir or Rh), followed by the insertion of CO generated in-situ. This step resulted in the formation of alkyl-CO-M-I intermediates. Subsequently, reductive elimination occurred, leading to the formation of alkyl-CO-I species. Finally, in the presence of water, these species were converted into the corresponding target carboxylic acids.

These halogenation approaches have made significant advancements in the CO2 chemistry. However, they are still limited by the requirement for high temperatures (170 ℃), high pressure (70 bar), and the use of several indispensable additives, which can result in challenging issues such as catalyst deactivation, poor selectivity, and an ambiguous understanding of the catalytic mechanism. Therefore, it is crucial to address these challenges in the future.

4. Photocatalysis strategyInspired by photosynthesis in nature, methodologies based on photochemistry have also been developed for the carboxylation of alcohols. A photoredox/nickel dual catalysis approach for the carboxylation of allylic alcohols with CO2 was successfully developed by Xi et al. using photoredox/nickel dual catalysis, producing exclusively linear acids with good Z/E stereoselectivity (Fig. 5a) [37]. Notably, water readily activates the alcohols with CO2, leading to the in-situ formation of an intermediate allylic hydrogen carbonate, followed by the oxidative addition of CO2 [28]. This protocol exhibited good tolerance towards a range of aryl and alkyl allylic alcohols, as well as propargylic alcohols, under visible light at room temperature.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. Carboxylation of α, β-unsaturated alcohols and/or benzyl alcohols with CO2 using the photocatalysis strategy. | |

In a groundbreaking study reported by Yu and coworkers (Fig. 5b), they utilized organic dyes, such as 2,4,5,6-tetrakis(diphenylamino)-isophthalonitrile (4DPAIPN) or 2,4,6-tris-(diphenylamino)-3,5-difluorobenzonitrile (3DPA2FBN), as photocatalysts to effectively catalyze the conversion of benzyl alcohols into carboxylic acids under visible light at room temperature [38]. After irradiation, a key intermediate, benzylic carbanion, was formed from the benzylic alcohols. The in-situ activation by acetic anhydride significantly enhanced the catalytic efficiency. Subsequently, the carbanion underwent nucleophilic attack on CO2, followed by protonation, resulting in the desired products. While in-situ esterification reactions were involved in both cases (Fig. 5a and b), we are inclined to categorize them as utilizing the photocatalysis strategy since photocatalysts are essential for these transformations. Xia and colleagues further extended the photocatalytic strategy for the carboxylation of benzyl alcohols using sodium tetraphenylborate (NaBPh4) and an Ir-photocatalyst (Ir[dF(CF3)ppy]2(dtbbpy)PF6) (Fig. 5c) [39]. Under mild visible light photoredox conditions, the neutral diphenyl boryl radical readily bonded to the oxygen atom of the alcohols to achieve in-situ activation. The B—O adducts then underwent homolysis of the C—O bond, generating a benzyl radical intermediate, which further transformed into the benzylic carbanion through single electron transfer reduction. Both protocols exhibited excellent compatibility with a wide range of substrates and demonstrated good tolerance towards various functional groups, accommodating primary, secondary, and even tertiary C—O bonds in diverse benzyl alcohols.

5. Conclusion and outlookUntil recently, the carboxylation of alcohols with CO2 has received limited attention. This perspective aims to provide an overview of this topic and highlight three main strategies for activating the C—O bond.

Unlike the in-situ esterification strategy, only limited allylic and benzyl alcohol substances could be transferred into carboxylic acids, the in-situ halogenation approach offers attractive methods for carboxylating simple alcohols into various carboxylic acids using clean H2 instead of metallic reducing agents, which simplifies the work-up process. However, this approach comes with inherent shortcomings, such as the use of corrosive additives, high temperatures and pressures, as well as possible catalyst deactivation. The combination of CO2 capture and its catalytic conversion may show promise for the future of CO2 chemistry. Catalysts with CO2 adsorption capacity, such as porous organometallic polymers [40-42], could potentially lower pressures and inhabit the possible catalyst deactivation. Moreover, the design of suitable ligands through electronic or steric effects may enhance catalyst stability and improve selectivity of the reaction.

As a more sustainable strategy, photocatalysis enables the carboxylation of alcohols with CO2 under much mild reaction conditions with a wide range of substrates, including allyl and benzyl alcohols. In the case of inactive aliphatic alcohols, sulfides. such as carbon disulfide or dimethyl sulfide could be utilized to achieve satisfactory outcomes [43,44]. Currently, the separation and purification of the resulting mixture are still challenges, developing suitable solid molecular photocatalytic materials, based on carbon nitride [45] and covalent organic frameworks [46], with excellent recycling capabilities, may accelerate the development of valorization of CO2 with alcohols.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsFinancial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22271060), the Department of Chemistry at Fudan University, and Nanjing Forestry University are gratefully acknowledged.

| [1] |

J. Artz, T.E. Muller, K. Thenert, et al., Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 434-504. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00435 |

| [2] |

M.D. Burkart, N. Hazari, C.L. Tway, et al., ACS Catal. 9 (2019) 7937-7956. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.9b02113 |

| [3] |

J.H. Ye, T. Ju, H. Huang, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 2518-2531. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00135 |

| [4] |

B.B. Asare Bediako, Q. Qian, B. Han, Acc. Chem. Res. 54 (2021) 2467-2476. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.1c00091 |

| [5] |

D.G. Yu, L.N. He, Green Chem. 23 (2021) 3499-3501. DOI:10.1039/D1GC90036F |

| [6] |

N. Onishi, Y. Himeda, Chem. Catal. 2 (2022) 242-252. DOI:10.1016/j.checat.2021.11.010 |

| [7] |

H. Maag, et al., Prodrugs of carboxylic acids, in: V.J. Stella, R.T. Borchardt, M.J. Hageman, et al. (Eds. ), Prodrugs: Challenges and Rewards Part 1, Springer, New York, 2007, pp. 703–729.

|

| [8] |

Q. Mei, X. Shen, H. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 30 (2019) 15-24. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2018.04.032 |

| [9] |

U. Cabulis, A. Ivdre, Curr. Opin. Green Sustain. Chem. 44 (2023) 100866. DOI:10.1016/j.cogsc.2023.100866 |

| [10] |

M. Aresta, A. Dibenedetto, Key issues in carbon dioxide utilization as a building block for molecular organic compounds in the chemical industry, in: CO2 Conversion and Utilization, American Chemical Society, 2002, pp. 54–70.

|

| [11] |

J. Davies, J.R. Lyonnet, D.P. Zimin, et al., Chem 7 (2021) 2927-2942. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2021.10.016 |

| [12] |

S. Saini, P.K. Prajapati, S.L. Jain, Catal. Rev. 64 (2020) 631-677. |

| [13] |

C.K. Ran, L.L. Liao, T.Y. Gao, et al., Curr. Opin. Green Sustainable Chem. 32 (2021) 100525. DOI:10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100525 |

| [14] |

S.S. Yan, Q. Fu, L.L. Liao, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 374 (2018) 439-463. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2018.07.011 |

| [15] |

A. Tortajada, F. Julia-Hernandez, M. Borjesson, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 15948-15982. DOI:10.1002/anie.201803186 |

| [16] |

A. Correa, T. Leon, R. Martin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 1062-1069. DOI:10.1021/ja410883p |

| [17] |

T. Moragas, J. Cornella, R. Martin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 17702-17705. DOI:10.1021/ja509077a |

| [18] |

P.J. Deuss, K. Barta, J.G. de Vries, Catal. Sci. Technol. 4 (2014) 1174-1196. DOI:10.1039/C3CY01058A |

| [19] |

Y. Jing, Y. Guo, Q. Xia, et al., Chem 5 (2019) 2520-2546. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2019.05.022 |

| [20] |

F.B. Guerra, R.M. Cavalcante, A.F. Young, ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 11 (2023) 2752-2763. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c05371 |

| [21] |

S.J. Blanksby, G.B. Ellison, Acc. Chem. Res. 36 (2003) 255-263. DOI:10.1021/ar020230d |

| [22] |

A.J.A. Watson, J.M.J. Williams, Science 329 (2010) 635-636. DOI:10.1126/science.1191843 |

| [23] |

X. Ren, Z. Zheng, L. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 310-313. DOI:10.1002/anie.201608628 |

| [24] |

W. Wan, S.C. Ammal, Z. Lin, et al., Nat. Commun. 9 (2018) 4612. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-07047-7 |

| [25] |

V. Dimakos, M.S. Taylor, Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 11457-11517. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00442 |

| [26] |

T. Mita, Y. Higuchi, Y. Sato, Chem. Eur. J. 21 (2015) 16391-16394. DOI:10.1002/chem.201503359 |

| [27] |

Y.G. Chen, B. Shuai, C. Ma, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 2969-2972. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01208 |

| [28] |

M. van Gemmeren, M. Borjesson, A. Tortajada, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 6558-6562. DOI:10.1002/anie.201702857 |

| [29] |

D. Liu, Z. Xu, H. Yu, et al., Organometallics 40 (2021) 869-879. DOI:10.1021/acs.organomet.0c00789 |

| [30] |

Q. Qian, J. Zhang, M. Cui, et al., Nat. Commun. 7 (2016) 11481. DOI:10.1038/ncomms11481 |

| [31] |

M. Cui, Q. Qian, J. Zhang, et al., Green Chem. 19 (2017) 3558-3565. DOI:10.1039/C7GC01391D |

| [32] |

T.G. Ostapowicz, M. Schmitz, M. Krystof, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 12119-12123. DOI:10.1002/anie.201304529 |

| [33] |

B.B. Asare Bediako, Q. Qian, Y. Wang, et al., Chem Catal. 2 (2022) 114-124. DOI:10.1016/j.checat.2021.11.004 |

| [34] |

Z. Sun, Y. Liu, J. Chen, et al., ACS Catal. 5 (2015) 6573-6578. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b01782 |

| [35] |

Y. Zhang, Y. Wang, Q. Qian, et al., Green Chem. 24 (2022) 1973-1977. DOI:10.1039/D1GC04569E |

| [36] |

Y. Li, Y. Wang, Y. Zhang, et al., ACS Catal. 13 (2023) 8025-8030. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.3c00374 |

| [37] |

Z. Fan, S. Chen, S. Zou, et al., ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 2781-2787. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c00418 |

| [38] |

C.K. Ran, Y.N. Niu, L. Song, et al., ACS Catal. 12 (2021) 18-24. |

| [39] |

W.D. Li, Y. Wu, S.J. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2022) 8551-8559. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c12463 |

| [40] |

Y. Shen, Q. Zheng, H. Zhu, et al., Adv. Mater. 32 (2020) 1905950. DOI:10.1002/adma.201905950 |

| [41] |

Y. Gu, S.U. Son, T. Li, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 31 (2021) 2008265. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202008265 |

| [42] |

Y. Shen, Q. Zheng, Z.N. Chen, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 4125-4132. DOI:10.1002/anie.202011260 |

| [43] |

D. Cao, Z. Chen, L. Lv, et al., iScience 23 (2020) 101419. DOI:10.1016/j.isci.2020.101419 |

| [44] |

C.Y. Tan, M. Kim, S. Hong, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202306191. DOI:10.1002/anie.202306191 |

| [45] |

S. Cao, J. Low, J. Yu, et al., Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 2150-2176. DOI:10.1002/adma.201500033 |

| [46] |

Q.J. Wu, J. Liang, Y.B. Huang, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 55 (2022) 2978-2997. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00326 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35