b School of Pharmacy, Xinxiang University, Xinxiang 453000, China;

c School of Food and Bioengineering, Xihua University, Chengdu 610039, China

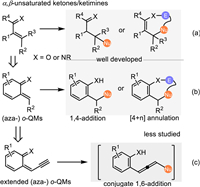

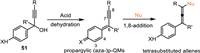

The conjugate 1,4-addition of α, β-unsaturated ketones/ketimines is deeed as a powerful approach for the formation of new C—C and C-heteroatom bonds (Scheme 1a) [1–4]. Among them, the (aza-)ortho-quinomethides (o-QMs), bearing a special α, β-unsaturated ketone/ketimine motif endowed with the dearomatized benzene, served as a highly reactive C4-synthon or Michael-acceptor in a variety of [4 + n] annulations or conjugate 1,4-additions, thus providing a facile pathway to construct structural diversified aromatic backbones (Scheme 1b) [5–9]. Due to the considerable lability but high reactivity, o-QMs are often prepared via the in-situ elimination of a leaving group from the o-hydroxybenzyl alcohols and its derivatives under mild acidic or basic conditions [10–15]. Accordingly, the ortho-aminobenzhydryl alcohol and its derivatives are utilized as the precursor of aza-o-QMs to perform the conjugate 1,4-addition involved reactions for accessing functionalized anilines or aza-cycloadducts [16–23]. Recently, Jiang's and Liu's group independently developed a cascade annulation of o-hydroxyl propargylic alcohols initiated by the conjugate 1,6-addition of in-situ generation of propargylic o-QMs under Brønsted acid catalysis, that expanded the synthetic potential of the o-QMs (Scheme 1c) [24,25]. Nevertheless, due to the decrease of reactivity and resulting regioselectivity, the study of the remote activation strategy with in-situ generation of o-QMs is still in its infancy.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Overview of the conjugate additions of (aza-)o-QMs. | |

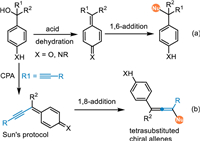

On the other hand, (aza-)para-quinomethides (p-QMs), which display an exocyclic methylene group and carbonyl/imine residue disposed in a para-position, performing as an intrinsic 1,6-Michael acceptor, have been widely applied in the conjugate 1,6-additions with various nucleophiles in recent years (Scheme 2a) [26,27]. Besides the pre-synthesized p-QMs [28–30], the 1,6-conjugate addition of in-situ generated p-QMs has made significant achievements over the past decade. This protocol effectively obviates preparing the unstable p-QMs, thus expanding the reaction scope and simplifying operations. Moreover, the electrophilic affinity of the p-QMs would be further transmitted to some remote sites via an extended π-system based on the principle of vinylogy, thereby allowing challenging 1,8- and even 1,10-additions (Scheme 2b) [31]. Sun and coworkers have pioneered this concept by introducing an alkynyl group conjugated with the p-QMs via the elimination of a water from para-hydroxybenzyl alcohols under CPA catalysis, providing an efficient approach for the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of tetrasubstituted chiral allenes [32].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Conjugate 1,6-/1,8-additions of in-situ generated (aza-)p-QMs. | |

Indole imine methides (IIMs), which feature an exocyclic methylene group and a conjugated endocyclic imine unit in the indole framework, perform as another highly reactive dearomatized electrophilic species for the straightforward functionalization of indoles. Similar to the QMs, IIMs are always prepared in-situ from the corresponding indolylmethanol and its derivatives under acidic or basic conditions via the elimination process (Scheme 3). In this context, 3-indolylmethanols and relevant derivatives are recognized as the most common one for the in-situ generation of 3-alkylideneindolenines, thus resulting in various conjugate 1,4-additions to afford structural diversified indole derivatives (Scheme 3b) [33–36]. Inspired by the principle of vinylogy and the seminal work of Tan [32], α-indolyl propargylic alcohols was discovered as an ideal precursor of the propargylic 3-IIMs for the conjugate 1,8-additions to access 3-indole containing tetrasubstituted allenes (Scheme 3a). Moreover, 2-indolylmethanols display similar behaviors compared to 3-indolylmethanols under acidic conditions, generating 2-IIMs with multiple electrophilic sites, thus initiating the nucleophilic attack via conjugate 1,4-additions or 1,6-additions, as well as 1,8-additions by using corresponding propargylic alcohols (Schemes 3c and d) [37,38]. Intriguingly, 6-indolylmethanols and 7-indolylmethanols were discovered by Antilla as the precursor of 6-IIMs and 7-IIMs respectively under acidic conditions, thus allowing 1,8-additions or formal 1,4-addions with nucleophiles to afford C6- and C7-functionalized indoles (Schemes 3e and f) [39].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 3. Conjugate 1,4-/1,6-/1,8-additions of in-situ generated IIMs. | |

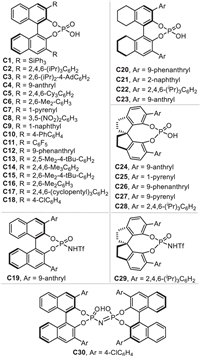

Due to the conjugate 1,4-addition of o-QMs and 3-IIMs has been extensively studied and well reviewed, we herein focus on summarizing recent progresses of the remote nucleophilic conjugate addition involved reactions rather than 1,4-additions via the in-situ formation of (aza-)p-QMs and IIMs in this review. Therefore, these newly developments of this topic will be discussed systematically and comprehensively in four parts: (1) remote conjugate additions of in-situ generated (aza-)p-QMs, (2) 1,6-addition reactions of in-situ generated 3-IIMs, (3) remote conjugate addition involved reactions of in-situ generated 2-IIMs, (4) remote conjugate additions of other type of in-situ generated IIMs. Most of the reactions are facilitated by the chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) [40–43], which has wide applications in the catalytic dehydration reactions. All the CPAs involved in this review are listed and numbered as shown in Fig. 1.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Chiral phosphoric acids (CPAs) C1-C30 involved in this review. | |

Generally, extended π-systems and electron-donation-group would make the transient dearomatized QMs stable but less reactive. Therefore, the pre-synthesized p-QMs with steric bulky alkyl group adjacent to carbonyl moiety has been widely explored in various nucleophilic 1,6-additions. However, the additional removal of the useless bulky substituents and pre-synthesizing procedures limit the synthetic diversity of this substrate. Inspired by the in-situ generated strategy of o-QMs, Sun and co-workers developed a CPA-catalyzed asymmetric 1,6-conjugate addition of the in-situ generated p-QMs from p-hydroxybenzyl alcohols 1 [44]. Pyrrole derivatives 2 with various substituents were well adapt in this reaction, delivering a series of chiral triarylmethanes 3 with a quartenary stereocenter in high yields with good to excellent enantioselectivities. Additionally, the indole was demonstrated to be feasible in this reaction under modified conditions (under the catalysis of C28). Moreover, styrenes 4 were workable in this protocol, giving the target products 5 in comparable results. The control experiment with Me-protected alcohol 1a-Me failed to give the desired product under identical condition, that implying this reaction probably proceeded via the 1,6-conjugate addition to the in-situ generated p-QMs. The Bn-protected pyrrole 2a-Bn was invalid in this protocol, indicating the CPA might act as a bifunctional role via the simultaneous formation of hydrogen-bond interactions with both two substrates. As depicted in Scheme 4, the smooth protonation of the tertiary alcohol 1 or the styrene 4 resulted in an extrusion of H2O to give the ion-pair Int-1. Then, a deprotonation induced by the phosphate anion gave rise to the reactive p-QMs, which incurred the 1,6-conjugate addition to fulfill the process (Scheme 4).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 4. Asymmetric 1,6-additions of in-situ generated p-QMs with pyrroles. | |

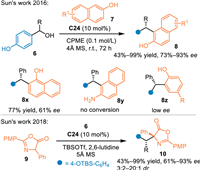

In 2016, Sun's group employed 2-naphthols 7 as nucleophiles in the reaction with p-hydroxybenzyl alcohols 6 under the catalysis of C24. A series of triarylmethanes 8 were obtained in moderate to excellent yields and enatioselectivities [45]. Besides, 1-naphthol was compatible in this reaction, delivering the target product 8x in high yield with lower enantioinduction. However, the 2-aminonaphthanene and phenol demonstrated to be inert in this reaction (8y and 8z). In 2018, Sun's group discovered that azlactones 9 were compatible in the reaction with p-hydroxybenzyl alcohols 6 under the catalysis of C24 via the conjugate 1,6-addition route [46]. A collection of chiral β, β-diaryl-α-amino acid derivatives 10 were obtained in moderate to high yields with good enantioselectivities and diastereoselectivities (Scheme 5).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 5. Asymmetric 1,6-additions of in-situ generated p-QMs with pyrroles and azlactones. | |

In addition to hydroxybenzyl alcohols, the styrene 11 endowed with an ortho- or para-phenol group serves as an alternative precursor for the in-situ generation of QMs via the protonation process under Brønsted acid conditions. The protonation of olefin gives rise to a carbocation species Int-2, then phosphate anion approaches the phenol group to generate the QMs, thereby inducing the nucleophilic addition reactions. In 2014, Sun and co-workers developed a convergent asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of the styrenes with Hantzsch ester in the presence of C1 [47]. A series of styrenes 11, including the ortho-/para-hydroxyl-substituted styrenes and indole-substituted 1,1-diarylethylenes 16, were well tolerant in the reaction with Hantzsch ester 12a for the construction of various chiral diarylethanes 13/15/18, which have wide applications in medicinal chemistry and agricultural domain. Furthermore, indoles 19 were smoothly applied in the nucleophilic conjugate addition with para-/ortho-hydroxyl styrenes 11 to synthesize chiral triarylethanes 20 under modified conditions. It was noteworthy that the electron-donating-group on one of the two aryls of the styrene was necessary for the efficient protonation of the vinyl group (benifit for the stabilization of the carbocation), that would enhance the reactivity and accelerate the reaction rate. Furthermore, the synthetic utility of the product was verified by a variety of derivatizations with phenol hydroxyl group (Scheme 6).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 6. Asymmetric transfer hydrogenation and conjugate nucleophilic addition of hydroxyl styrenes. | |

In 2017, Sun and co-workers discovered that alkynyl group affixed p-hydroxybenzyl alcohols 21 were applicable in the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation with Hantzsch ester under CPA catalysis [48]. Mechanistically, the in-situ generated p-QMs Int-3 was attacked by the hydride generated from the Hantzsch ester 24 via the conjugate 1,6-addition, affording a series of chiral diarylmethyl alkynes 23 in excellent yields with high enantioselectivities. Notably, this work expounded how an additive was involved in the improvement of the reaction outcome. Due to the simutaneous formation of pyridine by-product 24′ during the reaction process, whose basicity might passivate the activity of CPA, the reaction of 21a suspended in only 12% conversion, although with high enantiocontrol (89% ee). Thus, the addition of additional acid additive aims to neutralize the basicity of pyridine by-product becomes a key to promote the coversion of the reaction. Importantly, the acidity of the additive should be just enough to quench the pyridine by-product but without promoting the 1,6-addition in a nonselective pathway. After extensive investigations, the arylboronic acid 22 was found to be optimal to balance the conversion and enantio-control. Notably, the control experiment of pre-synthesized p-QMs Int-3a with Hantzsch ester 24 under the catalysis of S-C2 in the absence of the additive gave the desired product 23a in high yield with excellent enantionselecivity. Furthermore, the sequential addition of Hantzsch ester after the completion of dehydration step with the aid of S-C2 in the absence of boronic acid also smoothly delivered the desired product with satisfactory result. Such results indicated the pyridine by-product just retarded the first dehydration step but without passivating the second asymmetric nucleophilic addition process. Eventually, they conducted this protocol through the sequential procedures without requirement of the boronic acid, and the products were obtained in equally results (Scheme 7).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 7. The acid additive effect in the CPA-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of the Hantzsch ester. | |

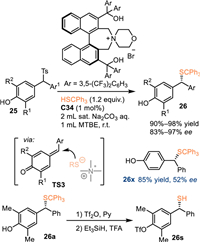

In 2018, Li and co-workers employed 4-hydroxybenzyl p-tolyl sulfones 25 as the precursor for the in-situ generation of p-QMs under basic conditions [49]. As a result, the phase transfer catalyst C34 was applicable for the asymmetric transformation of this substrate with tritylthiols, delivering a collection of α-substituted benzyl thioethers 26 in generally excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Unfortunately, 25x without substituents on the phenyl motif leaded the product 26x with inferior enantioselectivity probably due to relatively small steric effect. Notably, the trityl group could be smoothly removed in the presence of the trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) and triethylsilane (Et3SiH) without enantioselectivity erosion (Scheme 8).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 8. PTC-catalyzed 1,6-conjugate addition of in-situ generated p-QMs with tritylthiol. | |

Aza-p-QMs exhibit similar characteristics in respect to the nucleophilicity of the p-QMs. Accordingly, the N-protected amino benzhydryl alcohols are used as the precursor of the aza-p-QMs via the dehydration process under acid conditions. In 2017, the Sun's group disclosed an asymmetric N-alkylation of C2-C3 disubstituted indoles or carbazoles 28 with N-protected amino benzhydryl alcohols 27 under CPA catalysis [50]. The aza-p-QMs were generated in-situ and attacked by indoles or carbazoles through the aza-1,6-conjugate addition, giving N-alkylation products 29 in high yields with excellent enantiomeric excess. Meanwhile, C2-substituted indoles 30 were also employed in this protocol to undergo the C3-selective nucleophilic 1,6-additions for achieving chiral triarylmethanes 31 in satisfactory results. As expected, the N-methylated substrate 27-Me was not capable to proceed this process. The amide group could be smoothly transformed to amines via simple procedures (Scheme 9).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 9. Asymmetric N-alkylation of indoles or carbazoles via 1,6-conjugate addition of in-situ generated aza-p-QMs. | |

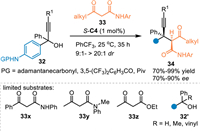

In 2020, Li and co-workers utilized propargylic alcohols 32 in the reaction with N-aryl-3-oxobutanamides 33 in the presence of S-C4, an unexpected 1,6-addition occurred exclusively without the generation of 1,8-adducts [51]. A series of diarylmethyl alkynes 34 containing vicinal quaternary and tertiary carbon stereocenters in high yields with good diastereo-/enantioselectivities. However, the N-protected amino benzhydryl alcohols and other ketones 33x-33z failed to participate in this protocol (Scheme 10).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 10. Asymmetric 1,6-additions of N-aryl-3-oxobutanamides with aza-p-QMs. | |

In 2021, Jiang and co-workers employed diphenylphosphine oxides 36 to react with propargylic tertiary alcohols 35 under Brønsted acid catalysis with the aid of ultrasonic irradiation [52]. A site-selective 1,6-hydrophosphination of in-situ generated aza-p-QMs was realized, giving diarylmethyl phosphorus oxides 37 bearing phosphorus-substituted quaternary carbon centers in high yields within about 5 min. Moreover, the chiral CPA was utilized in this reaction for the construction of chiral diarylmethyl phosphorus oxides. However, the product 38 was obatained with just 66% ee after extensive explorations (Scheme 11).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 11. Brønsted acid-catalyzed 1,6-hydrophosphination of the in-situ generated (aza-)p-QMs. | |

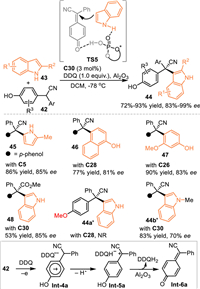

In 2022, Harutyunyanv and co-workers developed the first example of metal-catalyzed 1,6-addition of in-situ generated aza-p-QMs from 4-amino p-tolyl sulfones 39 with Grignard reagents [53]. In the presence of CuBr/dppf, this reaction smoothly delivered a wide variety of 4-sec-(alkyl) aniline derivatives 40 in good to excellent yields. Moreoer, the enantioselective version of this protocol proceeded smoothly by using chiral ferrocenyl diphosphine ligand Taniaphos C36 in the presence of CuBr, giving the chiral aniline derivatives in high yields with moderate to good enantioselectivities (Scheme 12).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 12. The conjugate 1,6-addition of Grignard reagents to in-situ generated aza-p-QMs. | |

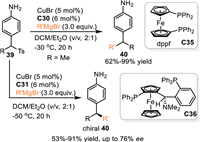

In addition to the acid-promoted dehydration of relevant alcohols or styrenes to access the p-QMs, Liu and coworkers discovered that the oxidization of 2-aryl substituted 4-(hydroxyphenyl)acetonitrile 42 was another pathway for accessing the p-QMs [54]. With the one-pot treatment of DDQ and chiral phosphoric acid C28 in DCM in the presence of Al2O3 at –78 ℃, the in-situ generated p-QMs was trapped by indoles 43 to afford the triarylmethanes 44 bearing all-carbon quaternary stereocenters in high yields with excellent enantioselectivities (Scheme 13). Besides indoles, other aromatic nucleophiles such as 1-naphthol, phenol and 2-methyl pyrrole demonstrated to be competent in this protocol. Moreover, 2-aryl substituted 4-(hydroxyphenyl)acetate was feasible to produce the p-QMs, thus allowig the asymmetric conjugate 1,6-additon in comparable result (product 48). It was noteworthy that O-Me protected diaryl acetonitrile failed to give the desired product 44a′ under the identical condition, the N-Me protected indole gave the desired product 44b′ with much lower enantioselectivity compared with NH-free ones. Such results indicated the hydrogen-bonding interaction betrween the CPA and two reaction partners was a key to the enantioinduction (TS5).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 13. Asymmetric 1,6-addition of the in-situ generated p-QMs from diarylacetonitrile by DDQ oxidization. | |

In 2021, Sun and coworkers expanded this oxidization strategy by using triarylmethanes for the in-situ generation of p-QMs in the presence of DDQ [55]. With the aid of C5, the pyrrole 2 approached the in-situ generated p-QMs in an enantioselective pathway, hence producing the valuable chiral tetraarylmethanes 50 in good yields with high enantioselectivities. It was noteworthy that the overloading of DDQ (1.5 equiv.) was detrimental to the enantiocontrol, that preventing the two-step protocol merging into one-pot operation. The methylated substrate smoothly delivered the desired product 50f without enantiocontrol due to the reactive intermediate was oxonium cation rather than p-QMs, that implying the execellent enantiocontrol might be ascribed to the hydrogen-bonding interaction bewttwen the chiral acid and the p-QMs. Moreover, control experiments verified the ortho-alkoxy group was indispensable (product 50g-i) for the enantiocontrol via its capability to form the hydrogen-bond rather than its steric hindrance (Scheme 14).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 14. Asymmetric 1,6-addition of the in-situ generated p-QMs from triarylmethanes by DDQ oxidization. | |

2.2. 1,8-Addition involved reactions of in-situ generated (aza-)p-QMs 2.2.1. Mono-step 1,8-addition to access tetrasubstituted allenes

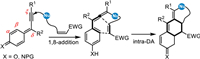

Based on the principle of vinylogy, the inserted vinyl or alkynyl in the cojugated π-system is deemed as an efficient and staightforward avenue to achieve remote activation [56–58]. In this context, the propargylic alcohols 51 affixed with the para-phenol/aniline emerged as the protocol for the generation of propargylic (aza-)p-QMs, that might result in the conjugate 1,8-addition to access the multi-substituted allenes or structural diversified cycles (Scheme 15).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 15. The generation of propargylic p-QMs for the conjugate 1,8-addition. | |

In 2017, the Sun's group reported the first example of 1,8-addition with alcohols 51 under Brønsted acid conditions, providing an efficient and unified method for the synthesis of tetrasubstituted allenes [32]. Under the catalysis of C17, the extended p-QMs was generated in-situ, thus attacked by 1,3-diketones 52 or thioacids 54 exclusively at ζ-position and giving tetrasubstituted chial allenes 53 in high yields with satisfactory stereoselectivities. It was noteworthy that alcohols without free hydroxyl (usually electron-rich substituent such as OMe, OAllyl and SMe for stabilization of the generated cations) on the para-site also smoothly delivered the chiral allenes 53y-53z in good yields with high diastereo-/enantioselectivities. In fact, this one would be protonated to form a cation species with a chial counter anion in the presence of CPA (TS5), thus resulting in an enantioselective SN1-type subsitution. Moreover, the enantiopure (+)−51a and (-)−51a were both subjected to this protocol and giving the chiral allene 55a with identical enantiomeric excess, indicating the enantiocontrol was just determined by the addition step (Scheme 16).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 16. Asymmetric conjugate 1,8-addition of in-situ generated propargylic p-QMs to access the chiral tetra-substituted allenes. | |

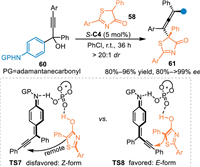

In 2018, Li and co-workers employed the propargylic alcohols 51 to proceed the conjugate 1,8-addition with thiazolones 56 and azlactones 58 with the aid of CPA [59]. On one hand, the thiazolone 56 with broad scope of substituents could be well-tolerated under the optimized conditions, smoothly producing the tetrasubstituted alkenes 57 bearing a quaternary stereocenter in high yields with remarkable diastereo- and enantioselectivities. On the other hand, the azlactone 58, which have similar structure and nucleophilicity compared with the thiazolone, was also workable in this protocol and afforded the tetrasubstituted chiral allenes 59 in good results under slightly modified conditions (Scheme 17).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 17. Asymmetric conjugate 1,8-addition of in-situ generated propargylic p-QMs with thiazolones and azlactones. | |

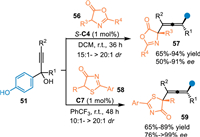

In 2019, the Li′s group extended this alkynylogous 1,8-addition to the aza-p-QMs [60]. By employing the aniline-incorporated propargylic tertiary alcohols 60, the aza-p-QMs was generated in-situ to react with thiazolones 58 under the CPA catalysis, delivering the chiral allenes 61 endowed with vicinal sulfur-containing quaternary stereocenters in excellent yields and stereoselectivities. In the control experiment of propargylic tertiary alcohols with the aid of CPA, the ESI-MS analysis undoubtly showed the molecular weight of aza-p-QMs, which indicated this reaction indeed proceeded via the conjugate 1,8-addition of in-situ generated aza-p-QMs. Notably, they also proposed a bifunnctional activation transition state for this reaction, in which the planar aza-p-QM intermediate was formed in an "E" form to react with the nucleophiles in a closer route assisted by the H-bonding interaction compared with the "Z" form (Scheme 18, TS7 vs. TS8) [61].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 18. Asymmetric 1,8-addition of in-situ generated propargylic aza-p-QMs with thiazolones. | |

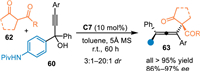

Almost simutaneously, Sun's group disclosed an asymmetric 1,8-addition of the aza-p-QMs with ketoesters 62 [61]. Under the catalysis of C7, propargylic alcohols 60 was dehydrated to form the aza-p-QMs, which was trapped by the nucleophile 62 to form 1,8-adducts in high yields with generally excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivities (Scheme 19).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 19. Asymmetric 1,8-addition of in-situ generated propargylic aza-p-QMs with ketoesters. | |

In 2022, Shi's group described an asymmetric cascade 1,8-addition/dearomative cyclization process of propargylic alcohols 60 with tryptamines with the aid of C20 [62]. The in-situ generated reactive aza-p-QMs was smoothly attacked by tryptamines 64 to form the allene intermediate with a dearomative indole imine motif, thus inducing the intramolecular Mannich-type cyclization process to form tetrasubstituted allenes 65 with vicinal contiguous carbon stereocenters with good to excellent stereoselectivities. Additionally, the p-hydroxylphenyl propargylic alcohol 51a was also engaged in this reaction to give the desired product in high yield albeit with moderate stereocontrol. However, the N-Me protected tryptamine 64-Me failed to participate in this reaction, which implied this reaction might proceed via a bifunctional activation mode through the interaction between the catalyst and the both two substrates (Scheme 20).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 20. Asymmetric tandem 1,8-addition and cyclization of in-situ generated propargylic aza-p-QMs with tryptamines. | |

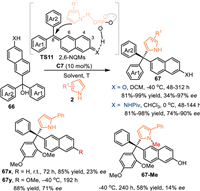

The 2-naphthol exhibited lower aromaticity but higher nucleophilicity compared with the simple phenol. Therefore, the 2-naphthol derived 6-(hydroxydiarylmethyl)naphthalen-2-ols 66O might be served as a valid precursor for the generation of the 2,6-naphthoquinone methides (2,6-NQMs), thus allowing the remote 1,8-addition with nucleophiles. In 2023, Li and co-workers pioneered this strategy by utilizing 6-(hydroxydiarylmethyl)naphthalen-2-ols 66 in the reaction with pyrroles 2 under the catalysis of C7, affording a series of tetraarylmethanes 67 in high to excellent yields with high enantioselectivities [63]. Meanwhile, the 6-(hydroxydiphenylmethyl)naphthalen-2-amines 66 N, which served as the precursor of the aza-2,6-NQMs, were well compatible in this reaction, giving the desired products in good results. Notably, the reactivity of the tertiary alcohol dramatically decreased when the naphthol was replaced by the naphthalene group 66x (no reaction under standard condition and inferior enantioinduction at room temprature). Moreover, the O-Me protected alcohol 66y or the N-Me protected pyrrol resulted in lower enantioselectivity under the identical conditions. Such results indicated this reaction proceeded via the CPA's dual activation mode (TS11). Besides, the ortho-heterosubstituent (OMe, F) on one of the aryls was essential for the reactivity and enantio-control, because it not only stabilize the carbocation intermediate but also played as the hydrogen-acceptor for the pyrrole motif in the transition state (Scheme 21).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 21. CPA-catalyzed 1,8-addition of the in-situ generated 2,6-NQMs with pyrroles. | |

Almost simultaneously, Sun and co-workers discovered that 8-hydroxyarylmethyl adorned naphthols and corresponding napthylamines 68 performed as the precursor for the generation of (aza-)2,8-naphthoquinone methides (2,8-NQMs) in the presence of chiral phosphoric acid via the elimination process, thus inducing a formal asymmetric aza-1,6-addition with indoles or carbazoles 28 at benzylic position to access a variety of remotely functionalized chiral naphthols and napthylamines 69 with excellent enantioselectivities [64]. Besides, other nucleophilies such as α-naphthol, β-naphthol and benzylic alcohols were well compatible in this protocol under slightly modified conditions (69x, 69y and 69z). Furthermore, the two phosphoric acids binded-transition states TS12 were proposed based on the DFT calculations, that explained the excellent remote enantioselecvity and the observed nonlinear results between the product ee and catalyst ee (Scheme 22).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 22. CPA-catalyzed 1,6-addition of the in-situ generated 2,8-NQMs with pyrroles. | |

2.2.2. Tandem 1,8-addition/annulation to access structurally complex cyclic skeletons

Progargylic (aza-)p-QMs play as a reactive electron-deficient α, β, γ, δ, ε, ζ-conjugated π-system, featuring multiple reactive electrophilic sites, thus leading rich synthetic versatility for this intermediate. Besides terminal ζ-position, the δ-position is another latent reactive electrophilic site in this reactive species. Therefore, the progargylic (aza-)p-QMs would serve as a biselectrophilic 3C synthon to proceed cascade [3 + n] annulations with dinucleophiles for the construction of polycyclic structures (Scheme 23).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 23. Conjugate 1,8-addition initiate cyclizations of the in-situ generated propargylic (aza-)p-QMs. | |

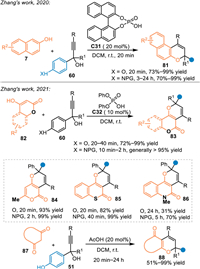

In 2020, Li and co-workers realized the first example of asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the in-situ generated progargylic aza-p-QMs with 3-substituted 1H-indoles 70 under CPA catalysis [65]. Catalyst C22 promoted the dehydration of propargylic alcohols 60 and delivered extended aza-p-QMs, thus inducing the 1,8-addition to afford chiral allene intermediate (TS13). Subsequently, a hydrogen-bonding assisted protonation occurred to form the benzylic cation (TS14), which initiated the intramolecular cyclization process to give the chiral pyrrolo[1,2-a]indole skeleton 71. Notably, the pre-synthesized racemic allene 72 was successfully engaged under the established conditions, giving the desired product 71a in a comparable result. This result validated this reaction indeed proceeded via a cascade 1,8-addition/intramolecular cyclization process. Additionally, propargylic alcohol 51a with a p-hydroxy phenyl substituent was feasible for this conversion to give a corresponding product in good result. However, the propargylic alcohol 73a with the acetamido group at the ortho-position delivered the product in inferior conversion without enantioselectivity. The propargylic alcohols 60-Me without an NH-free group were inactive in this protocol (Scheme 24). Almost simultaneously, Zhang and co-workers disclosed the racemic version of this reaction under the catalysis of camphorsulfonic acid [66].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 24. CPA-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the in-situ generated propargylic aza-p-QMs with indoles. | |

In 2023, Shi and coworkers extended this protocol by using the pro-axialchiral 3-arylindoles 74 in the reaction with propargylic alcohols 75/77 for the synthesis of axially chiral 3-arylindoles 76 including the ones 78 containing the chiral pyrrolo[1,2-a]indole motif with a central chiral center with excellent diastereo- and enantioselectivities [67]. Notably, the propargylic alcohol 79 without OMe group on the phenyl ring failed to participate in this reaction, implying this reaction proceeded via the formation of p-QMs other than the generation of the carbocation intermediate. Furthermore, the p-OMe substituted phenyl group of the propargylic alcohol was superior to the p-OH substituted one 80 with respect to the enantiocontrol, indicating the formation of p-QM cation species (TS15), which would form an ion-pairing interaction with the chiral phosphoric acid anion, was essential for the enantioinduction (Scheme 25).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 25. CPA-catalyzed [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the in-situ generated propargylic aza-p-QMs with 3-arylindoles. | |

The phenol and its derivatives, particularly the naphthol and the 4-hydroxycoumarin, demonstrated to be a versatile dinucleophilic 3C synthon for cascade [3 + n] annulations to access oxa-heterocycles [68–70]. As a result, Zhang and co-workers employed 2-naphthols 7 in the reaction with in-situ generated propargylic p-QMs for [3 + 3] annulations under the catalysis of C31 in 2020 [71]. An array of functionalized naphthopyrans 81 were synthesized in execellent yields within 20 min. Meanwhile, p-aminophenyl propargylic alcohols were also tolerable in this reaction to afford corresponding adducts in good results within prolonged reaction time. In 2021, this group extended this strategy by using 4-hydroxycoumarins 82 or 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds 87 under the catalysis of C32 [72]. On one hand, an array of 4-hydroxycoumarins 82 and its analogs, such as 4-hydroxythiocoumarin and 4-hydroxyquinolinone, were applicable in the reaction with in-situ generated (aza-)p-QMs, affording pyranocoumarins 83 in relatively low to high yields. On the other hand, cyclic 1,3-diketones 87 were also well tolerated in this reaction to afford various pyran products 88 in generally high yields (Scheme 26). Moreover, these valuable coumarin-containing heterocycles indeed exhibited significant α-glucosidase inhibitory activity in their initial bioactivity explorations.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 26. Cascade [3 + 3] cycloaddition of the in-situ generated propargylic aza-p-QMs with phenols. | |

2-Indolylmethanols were deemed as a kind of intrigued substance because of the changeable electron affinity at C3 position. The Shi's group has made significant achievements with this property to access structural diversified indole-based skeletons [37]. In principle, this substrate could be served as a dinucleophilic 4C synthon in respect to the nucleophilicity of C3 position and the hydroxyl group to undergo [4 + n] cycloadditions. Therefore, Zhang and co-workers employed the in-situ generated propargylic p-QMs to react with 2-indolylmethanols 91 for the [4 + 3] annulation in the presence of C31 [73]. Interestingly, the 2-indolylmethanol 89 without a steric bulky group at benzylic site exclusively gave the 1,6-adduct 90 toward C3 position of the indolylmethanol. Probably, due to the small steric hindrance that would accommodate the formation of a triarylmethane unit. In contrast, 2-indolylmethanols 91 with steric diaryl groups at the benzylic site impelled the reaction proceeding via the 1,8-addition mediated [3 + 4] annulation process. A series of valuable polysubstituted indole-fused oxepines 92 were facilely obtained in high yields via this protocol (Scheme 27).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 27. Cascade [3 + 4] cycloaddition of the in-situ generated propargylic p-QMs with 2-indolylmethanols. | |

In view of the 4-hydroxystyrene motif in the allene species generated from the 1,8-addition of the progargylic (aza-)p-QMs, which would be served as an electron-rich diene for the Diels-Alder reaction with appropriate dienophiles to access ring-fused skeletons (Scheme 28).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 28. The resulting-formed 4-hydroxystyrene motif inducing intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction. | |

Based on this consideration, Wang and co-workers employed propargylic alcohols 51 to react with 1,3-disubstituted 2-naphthols 93 [74], whose nucleophilicity has been confirmed in various catalytic dearomative reactions along with the generation of an unsaturated ketone fragment [75]. As expected, an asymmetric conjugate 1,8-addition mediated intramolecular Diels-Alder reaction occurred in the presence of C8, giving a variety of structurally complex polycyclic skeletons 94 in good to excellent yields with remarkable stereoselectivities. Notably, the isolated allene intermediate 95 was determined in high enantioselectivity, which could smoothly deliver the Diels-Alder product 94a in the absence of the chiral acid with comparable ee value. This result undoubtly expounded the stereocontrol of this cascade multiple dearomative process was determined by the first 1,8-addition process, the stereo-carbon center and axial chirality would induce an enantioselective Diels-Alder reaction. This protocol represented an elegant asymmetric approach via multiple dearomatization processes in two different aromatic molecules under mild conditions. That confirmed this strategy was an efficient route to obtain structurally complex polycyclic systems (Scheme 29).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 29. Cascade 1,8-addition and intramolecular Diels–Alder reaction of the in-situ generated propargylic p-QMs with naphthols. | |

3. 1,6-Addition reactions of in-situ generated 3-IIMs

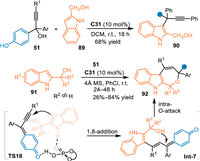

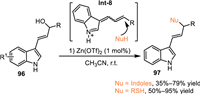

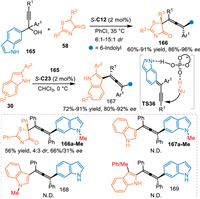

3-Indole imine methides (3-IIMs) emerged as energetic intermediates for the functionalization of indoles through the formal 1,4-addition process [33–36]. The 3-indolylmethanol and its derivatives were deemed as effective precursors to form 3-IIMs under acid or basic conditions via an elimination process. In 2017, Bernardi and co-workers extended this protocol to conjugate 1,6-addition by using indole-based allylic alcohol 96 via the generation of vinylogous indole imine methides Int-8 under Lewis acid catalysis, that extended the synthetic potential of the 3-IIMs (Scheme 30) [76].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 30. The conjugate 1,6-addition of in-situ generated vinyl 3-IIMs. | |

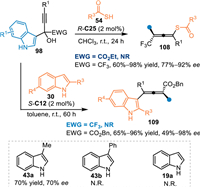

In 2020, Lu's group employed α-indolyl-α-trifluoromethyl propargylic alcohols 98 as the precursor of propargylic-IIMs under acid conditions [77]. Under the catalysis of R-C24, the alkynylogous 3-IIMs was generated (TS21), which was attacked by 1-naphthols 99 in a stereoselective manner at δ-position, thus producing tetrasubstituted chiral allenes 100 with wide substrate scope in high yields and enantioselectivities. However, 2-naphthols 7 failed to give the tetrasubstituted allene [78] under the identical condition, but producing the valuable chiral naphthopyran 101 by a subsequent O-nucleophilic cyclization process of the allene species Int-9 in good results under modified conditions. It was noteworthy that p-hydroxybenzyl derived propargylic alcohols 51b smoothly delivered the chiral allene 102 or naphthopyran 103 with naphthols via the in-situ formation of propargylic p-QMs under standard conditions, albeit without enantio-control. The OMe-protected naphthol or N-Me-protected propargylic alcohols failed to participate in this reaction, which indicated this reaction probably proceeded in a dual-activation mode (Scheme 31).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 31. The conjugate 1,6-addition and the following cyclization of the in-situ generated 3-IIMs with naphthols. | |

In 2022, the Lu's group employed 3-indolyl propargylic alcohols for the convergent synthesis of chiral 3, n'-bis(indolyl)methanes (3, n'-BIMs) under CPA catalysis [79]. When propargylic alcohols 98 bearing phenylethynyl group were used in the reaction with 3-substituted indoles 43 in the presence of C10, a conjugate 1,6-addition initiated cyclization occurred smoothly to afford the chiral cyclic 3,1′-BIMs 104 featuring quaternary stereogenic centers in moderate to excellent yields with generally remarkable enantiomeric excesses. Notably, the allene intermediate Int-10 was observed and isolated with inferior enantioselectivity, that indicated this reaction probably proceeded via a cascade 1,6-addition and intramolecular hydroamination process. Moreover, the excellent enantio-control for this reaction was determined by the intramolecular cyclization step via a dynamic kinetic resolution process. Interestingly, other type of 3-indolyl propargylic alcohols 105 with different substituent, such as the alkyl-alkynyl, alkenyl, alkyl, and aryl groups, performed an asymmetric 1,4-type addition under modified conditions. A wide range of 3,3′-BIMs 107 and 3,2′-BIMs 106 were obtained in good results by using relevant indoles 19 and 3-substituted indoles 70, respectively (Scheme 32). Furthermore, these obtained products exhibited promising antibacterial activity.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 32. The convergent asymmetric synthesis of the 3, n'-BIMs via the conjugate additions of the in-situ generated 3-IIMs. | |

In 2021, Li and co-workers adopted thiolacetic acids 54 as nucleophiles to perform the asymmetric 1,6-addition with α-indolyl-α-trifluoromethyl propargylic alcohols 98 under CPA catalysis [80]. A wide range of axially chiral sulfur-containing tetrasubstituted allenes 108 were obtained in high yields and enantioselectivities. However, α-(3-indolyl)propargylic alcohol with α-ester group was not tolerable in this protocol. Subsequently, this group discovered that 2-substituted indoles 30 were feasible in this conjugate 1,6-addition under modified conditions, furnishing the tetrasubstituted chiral allenes 109 in generally high yields with moderate to excellent enantioselectivities [81]. Besides, 3-Me-indole 43a was compatible in this reaction, giving the desired product in 70% yield with 70% ee. However, 3-Me-indole 43b and indole 19a failed to participate in this protocol (Scheme 33).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 33. The asymmetric 1,6-addition of the in-situ generated propargylic 3-IIMs with thioacetic acids and indoles. | |

4. Remote conjugate addition involved reactions of in-situ generated 2-IIMs

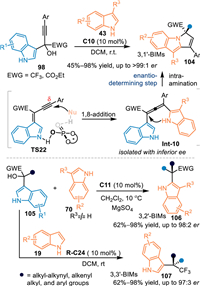

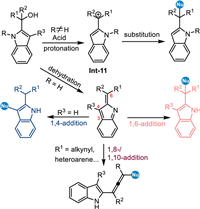

Pioneered by the work of Martin [82] and Han [83,84], 2-indolylmethanols emerged as another powerful reactants to achieve structurally diversified indole derivatives via the acid-promoted dehydration nucleophilic functionalizations [37,38]. Mechanistically, N-protected 2-indolylmethanols, the hydroxyl group is readily protonated to give benzylic carbocation intermediate Int-11, thus allowing formal nucleophilic substitutions rather than nucleophilic conjugate additions. In contrast, the NH-free 2-indolylmethanols prefer to give the 2-indole imine methides (2-IIMs) via the dehydration process under acid conditions, that enabling nucleophilic conjugate additions at benzylic position (formal 1,6-addition). It is noteworthy that an umpolung reaction would be induced at C3 position (formal 1,4-addition) of the 2-IIMs, that provides a novel approach for the nucleophilic functionalization of indoles. In this context, the Shi's group has made significant developments, achieving a variety of umpolung C3-functionalizations and that initiating cascade cyclizations under Brønsted acid conditions [85–89]. For the theme of this review, we will discuss the transformations at the benzylic site via the conjugate 1,6-addition and that initiated cascade cyclizations. Intriguingly, the extended 2-IIMs with the alkynyl-group and even the hetero-arene would result in challenging 1,8- and 1,10-additions (Scheme 34).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 34. The conjugate addition of in-situ generated 2-IIMs from 2-indolylmethanols. | |

4.1. Mono-step 1,6-/1,8-/1,10-addition of the 2-IIMs

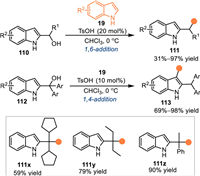

Generally, C3-unsubstituted 2-indolylmethanols would be transformed to 2-IIMs with two electrophilic sites under acidic conditions, including C3 and benzylic sites. Therefore, it is a challenging task to achieve an elegant regioselective nucleophilic addition with this type of 2-indolylmethanols. In 2017, Shi and co-workers discovered a substrate-controlled regioselective nucleophilic arylations of 2-indolylmethanols 110/112 with indoles 19 under acidic conditions [90]. The 2-indolylmethanol 110 bearing a phenyl group proceeded the 1,6-addition at benzylic position with indoles 19 in the presence of catalytic amount of TsOH, a series of bis(indolyl)methane 111 were produced in moderate to excellent yields. Interestingly, the 2-indolylmethanol 112 containing two aryls at the benzylic site, thus increasing the steric repulsion and compelling the nucleophilic addition at the C3-position. A wide range of 3,3′-bisindole derivatives 113 were smoothly obtained in high yields via this pathway. However, the tertiary alcohol also reacted with indoles at benzylic site to give 111x-111z in good yields, implying the existence of the two aryl groups was essential for the umpolung pathway (Scheme 35).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 35. Substrate-controlled regioselective arylations of 2-indolylmethanols. | |

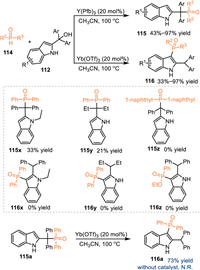

The diphenylphosphine oxide performs as an effective nucleophilic phosphorylation reagent for the synthesis of phosphine reagents. As a result, the utilization of diphenylphosphine oxides in the reaction with 2-indolylmethanols under acid catalysis might result in the formation of structural diversified indole-based phosphines. In 2018, Wang and co-workers discovered a switchable conversion of 2-indolylmethanols 112 with diphenylphosphine oxides 114 by the utilization of different Lewis acids [91]. Under the catalysis of Y(Pfb)3, the benzylic phosphorylated products 115 were produced in moderate to excellent yields. In contrast, the Yb(OTf)3, which features stronger acidity, promoted C3-functionalized products 116 via the 1,4-addition pathway, giving a plenty of valuable triphenyl phosphine oxides in moderate to high yields. The control experiment of 115a with the treatment of Yb(OTf)3 under 100 ℃ smoothly gave rise to the C3-functionalized products 116a, that indicated the C3-phosphorylated product was a thermodynamic product and the benzylic product probably was an intermediate during the formation of the C3-phosphorylation process. Meanwhile, the treatment of 115a at 100 ℃ in the absence of Yb(OTf)3 delivered no desired product, indicating this rearrangement was not a thermal stimulation process (Scheme 36).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 36. Lewis acid-controlled regioselective phosphorylation of 2-indolylmethanols. | |

Almost simultaneously, Chen and co-workers discovered a Brønsted acid promoted regio-divergent phosphorylation of the 2-indolylmethanol 112 with diarylphosphine oxides 114 [92]. With the aid of TsOH, the benzylic phosphorylated product 115 was produced in good yields within 15 min to 6 h at ambient temperature. When the reaction was subjected to stronger acid TfOH at higher temperature, the C3-phosphorylation occurred to give indole-based triarylphosphine oxides 116 in moderate to good yields. Consistent with Wang's findings, the control experiment in Chen's work also indicated the C3-phosphorylated product was dominantly derived from the benzylic-functionalized via a [1,3]-P migration process under a slightly harsh condition. Notably, the N-alkylated alcohol has lower reactivity in the reaction with the diphenylphosphine oxide, giving the benzylic phosphorylated products 115-Me/115-Bn in moderate yields after prolonged reaction time (Scheme 37).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 37. Brønsted acid-catalyzed regiodivergent phosphorylation of 2‐indolylmethanols. | |

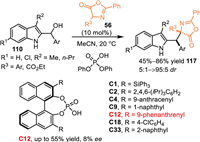

The 2-indolylmethanol was substituted at C3-position was a direct route to exclude C3-functionalization, thus allowing the 1,6-addition and its successive N-cascade process. In 2017, Shi and co-workers utilized azlactones 56 as nucleophiles to react with the in-situ generated C3-blocked 2-IIMs [93]. The acid-promoted dehydration of 2-indolylmethanols 110 gave rise to the formation of 2-IIMs, which was trapped by the azlactones to exclusively give the 1,6-adducts 117 in good yields and diastereoselectivities. Moreover, a series of CPA were explored in this protocol to fulfill its enantioselective pattern, though no positive results was observed (Scheme 38).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 38. Brønsted acid-catalyzed benzylic functionalization of 2‐indolylmethanols with azlactones. | |

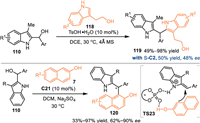

In 2020, the Shi's group developed a benzylic-functionalization of 2-indolylmethanols 110 with tryptophols 118 under the catalysis of TsOH, the 2,2′-bisindolylmethane framework 119 was observed in generally high yields [94]. Furthermore, after an extensive investigation of the CPAs and other parameters, such as solvents, molecular sieves and temperatures, this reaction was realized in up to 50% yield with 48% ee. Subsequently, the Shi's group developed a CPA-catalyzed asymmetric benzylic substitution of the 2-indolylmetanol 110 with 2-naphthols 7. The acid-promoted dehydration delivered the 2-IIMs, thus inducing the following enantioselective nucleophilic attack with the dual aid of the C21. A collection of chiral triarylmethane derivatives 120 were produced in moderate to high yields with promising enantioselectivities (Scheme 39).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 39. The CPA-catalyzed asymmetric benzylic arylations of 2-indolylmethanols. | |

The conjugate 1,6-addition of indolylmethanols and hydroxybenzyl alcohols with nucleophiles emerged as an efficient approach for the synthesis of various multi-aryl substituted methanes. Especially, that might provide a facile approach to access desirable tetra-arylmethane derivatives, which belong to a class of spherical molecule and is of great significance in drug discovery and functional materials [95–97]. Nevertheless, the enantioselective synthesis of tetra-aryl substituted methanes still remains elusive due to the overwhelming steric repulsion and enantiodifferentiation encountered during the stereo-center formation stage. In 2020, Sun and co-workers developed a stereoconvergent synthesis of pyrrole-based tetra-aryl methane derivatives 122 by the conjugate addition of pyrroles 2 to the in-situ generated p-QMs or 2-IIMs under the CPA catalysis [98]. Interestingly, the ortho-alkoxyl group substituted-aryl contained alcohols delivered generally excellent stereocontrol in the conjugate addition. However, the ortho-alkyl or meta-/para-OMe substituted ones resulted in inferior results. Based on the proposed transition states TS24 and TS25, the o-OMe or other heteroatom groups would form a stable hydrogen bond with the pyrrole motif. However, for the minor TS25, the methoxy group was impelled to orientate towards the cyclohexyl groups of the catalyst, leading to a longer and weaker hydrogen bond between the catalyst and the pyrrole nitrogen. Therefore, the energy of TS25 was higher than the TS24 (2.4 kcal/mol), that enforced the addition step via the TS24 in an excellent enantiosetive mode. However, the ortho-methyl substituted one has no hydrogen bond interaction with the pyrrole motif (TS26 and TS27), thus made the methyl group rotates away from the cyclohexyl substituents to lower the energy. As a result, the energy of the TS27 is only 0.6 kcal/mol higher than the TS26, leading to a low differentiation and low enantioselectivity. With this strategy, p-hydroxybenzyl alcohols 121 and 2-indolymethanols 123 were well tolerated to provide two libraries of structurally distinct chiral tetra-aryl substituted methanes in remarkable yields with high enantioselectivities (Scheme 40).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 40. Asymmetric synthesis of chiral tetra-arylmethanes with in-situ generated p-QMs and 2-IIMs. | |

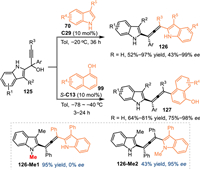

Based on the vinylogy principle, the propargylic 2-IIMs would transmit the electrophilic site to some remote site, thus achieving 1,8- and even 1,10-addition. In 2020, Sun and co-workers developed a CPA-promoted asymmetric 1,8-addition of propargylic 2-indolylmethanols 125 with 3-substituted indoles 70, providing a number of multi-functionalized tetrasubstituted allenes 126 in excellent yields with high enantioselectivities [99]. Besides indoles, 1-naphthols 99 were well compatible in this protocol. Notably, the N-Me protected 125a-Me smoothly gave the desired product 126-Me1 but without enantiocontrol. The N-Me protected 3-phenyl indole was well tolerant in this protocol to give the product 126-Me2 in good result. Such results implied the hydrogen-bonding interaction between the 2-IIMs and the catalyst was crucial for the excellent stereoinduction (Scheme 41).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 41. Asymmetric 1,8-addition of in-situ generated propargylic 2-IIMs with indoles and 1-naphthols. | |

Besides the alkynyl group, the heteroaryl also played as an excellent π-system for the transfer of the HOMO or LUMO effect, thus affording remote functionalizations on the heteroarene [100–103]. In 2021, Sun and co-workers employed the benzylic thiophene contained 2-indolyl methanol 128 in the reaction with pyrroles 2 under the catalysis of C22 [104]. Under the catalysis of the C22, 2-indolylmethanols 128 were dehydrated to form 2-IIMs with a conjugated thiophene motif, thus lowering the LUMO of the thiophene and inducing an asymmetric nucleophilic dearomative 1,10-addition with pyrroles 2 by the CPA's dual activation. A series of densely functionalized dearomatized thiophenes 129 were obtained in excellent yields with high enantioselectivities and E/Z selectivities. Notably, the methyl-substituted alcohol gave the 1,6-adduct triarylethane 130′ as a major product in 77% yield with 84% ee, that was ascribed to the lower steric hindrance at the benzylic position. As a result, the 1,10-adduct 130 was obtained in 16% yield with excellent enantioselectivity and E/Z selectivity. Additionally, the furan and selenophene were successfully compatible in the extended 2-IIMs, giving the dearomatized products 131 and 132 in comparable results. On the other hand, N-methyl protected indole and pyrroles were workable in this protocol, offering the desired products (129a-Me, 129b-Me and 133-Me) in moderate yields with excellent enantioselectivities and E/Z selectivities. However, the NH-free indoles produced the desired products 133 with inferior stereoselectivity albeit in high yield. The N-methyl indole-based alcohol delivered the product 129Me-a with a rotation-hindered axis, thus resulting an additional challenge for the stereocontrol in a single process. Besides, the QM-conjugated thiophenes, including the p-QMs, aza-p-QMs, and o-QMs conjugated ones (135–137), smoothly proceeded the additions but with inferior enantioselectivities and E/Z-control (Scheme 42).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 42. Asymmetric dearomatization of thiophenes by 1,10- addition of in-situ generated indole imine methides. | |

4.2. Cascade 1,6-addition and cyclization of the 2-IIMs

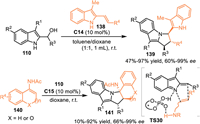

Alternatively, C3-substituted indolylmethanols would perfom as C, N-dipolar surrogates in the presence of Brønsted acid, thus initiating the cascade [3 + n] annulations with nucleophiles to afford indole-based heterocycles. In 2016, Schneider and co-workers developed a CPA-catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the indolylmethanol 110 with 2-vinylindoles 138 [105]. The in-situ generated 3-substituted 2-IIMs and 2-vinylindoles were then binded by the double hydrogen bonding of the CPA to forge ensusing enantioselective [3 + 2] cycloaddition. A wide range of pyrrolo[1,2-a]indoles 139 with three continuous stereogenic centers were produced as a single diastereoisomer in excellent yields and enantioselectivities. Subsequently, this group adopted cyclic enamides 140 as the nucleophilic 2C synthon in the reaction with 2-indolylmethanols to perform [3 + 2] cycloaddition in the presence of C15, generating the indolo[1,2-a]indoles 141 in good results (Scheme 43) [106].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 43. CPA-catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the 2-indolylmethanols. | |

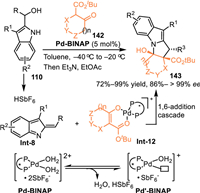

In 2020, Schneider and co-workers developed an enantioselective [3 + 2] cycloaddition of the 2-indolylmethanol 110 with β-keto esters 142 by employing chiral Pd-aqua complex in a cooperative catalysis [107]. The Pd-aqua complex performed as a Brønsted acid/base system by the equilibrium between Pd-catalyst A and Pd−OH-complex B. The Brønsted basic complex B deprotonated the keto-ester to form the chiral Pd-enolate Int-12, and the concomitantly released HSbF6 facilitated dehydration to form the 2-IIMs, thus inducing the enantioselective cascade conjugate 1,6-addition and N-cyclization to provide enantio-enriched pyrrolo[1,2-a]indoles 143 in excellent yields and stereoselectivities (Scheme 44).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 44. Palladium-catalyzed asymmetric [3 + 2] cycloaddition of 2-indolylmethanols with β-keto esters. | |

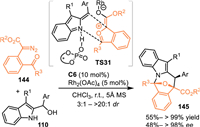

Carbonyl ylides, which were in-situ generated by the insertion of the metal-carbene into carbonyl group, performed as highly reactive 1,3-dipolar surrogates to undergo various cycloaddition including the enantioselective conversions [108,109]. In 2021, Schneider's group extended the 2-IIMs to perform [3 + 3] cycloadditions with transient carbonyl ylides enabled by the cooperative catalysis of Rh2(OAc)4 and chiral phosphoric acid C6 [110]. The Rh-enabled the formation of Rh-carbene intermediate, that was trapped by the carbonyl group to form the reactive carbonyl ylide (TS31). Subsequently, the in-situ generated hydrogen-bonded 2-IIMs by the CPA was involved in the reaction with the above-resulted carbonyl ylide species via a cascade [3 + 3] cycloannulation process in an enantioselective pathway (TS31), delivering oxa-bridged azepino[1,2-a]indoles 145 in excellent yields with moderate to high diastereo- and enantioselectivities (Scheme 45).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 45. Asymmetric [3 + 3] cycloaddition of the 2-indolylmethanol with carbonyl ylides. | |

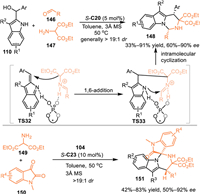

Azomethine ylides served as versatile 1,3-dipolars in a variety of [3 + n] cycloadditions to prepare densely functionalized heterocycles [111–113]. In 2017, Shi's group employed this reactive species to react with the in-situ generated 3-substituted 2-IIMs to fulfill a 1,6-addition induced cascade [3 + 3] cycloaddition [114]. Under the catalysis of S-C20, the azomethine ylide was formed via the condensation of benzaldehydes 146 and amino-esters 147, then resulted in the cascade 1,6-addition to the in-situ generated 2-IIMs and intramolecular cyclization with the aid of double hydrogen bonding interactions of the CPA. As a result, a collection of tetrahydropyrimido[1,6-a]indole skeletons 148 were obtained in moderate to good yields, as well as the stereoselectivities. Besides, the isatin-derived azomethine was demonstrated to be workable in this protocol, giving the spirooxindoles 151 in considerable yields with moderate to good enantioselectivities and excellent diastereoselectivities (Scheme 46) [115].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 46. Asymmetric [3 + 3] cycloaddition of the 2-indolylmethanol with azomethine ylides. | |

5. Remote conjugate addition involved reactions of other in-situ generated IIMs

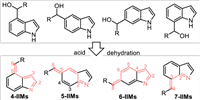

Theoretically, besides 2-/3-indolylmethanols, other type of indolylmethanols with methylol group at C4, C5, C6, or C7 position would result in corresponding 4-, 5-, 6-, 7-IIMs via the acid-promoted dehydration process, thus allowing corresponding remote activation for the convergent synthesis of functionalized indole-backbones (Scheme 47).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 47. The generation of abnormal 4-/5-/6-/7-IIMs from corresponding indolylmethanols. | |

In 2018, Antilla and co-workers pioneered an elegant remote addition with 6- and 7-indolylmethanols 157/152 under the catalysis of CPA [39]. On one hand, the 7-indolylmethanol 152 was dehydrated smoothly to give 7-IIMs, that was smoothly attacked by indoles 30 or pyrroles 2 via the formal 1,4-addition with the aid of hydrogen bonding interaction of the CPA. Interestingly, N-Me protected indolylmethanol worked well in the reaction with the NH-free indole, delivering the chiral triarylmethanes 155 in good yields with high enantioselectivities. However, the N-Me protected indole gave the product 156 with 13% ee in the reaction with the N-Me protected indolylmethanol. These results implied that a formal SN1 substitution was compatible in this catalytic system. On the other hand, they also explored the reactivity of 6-indolylmethanols 157 under the catalysis of CPA. Mechanistically, the acid-promoted dehydration of the 6-indolylmethanol gave rise to the 6-IIMs, that induced the conjugate 1,8-addition with indoles to afford the desired triarylmethanes 158 in excellent outcomes. Notably, the N-Me protected indolylmethanol failed to give the product 161 with good enantiocontrol, that implied the formation of 6-IIMs was crucial for the stereoinduction. This protocol provides a convergent pathway for the functionalization of the indole (Scheme 48).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 48. Asymmetric 1,4- and 1,8-addition of the in-situ generated 7-/6-IIMs. | |

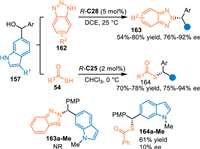

In 2020, Li and co-workers extended the conjugate 1,8-addition of the in-situ generated 6-IIMs with heteroatom nucleophiles [116]. By employing 6-indolylmethanols 157 as the precursor of 6-IIMs in the presence of R-C28, benzotriazoles 162 were successfully trapped to perform the asymmetric conjugate 1,8-addition, delivering the N2-selective alkylation products 163 in good yields and enantioselectivities. Additionally, sulfur nucleophiles 54 including thioacetic and thiobenzoic acids were applicable in this protocol under the slightly modified condition, giving the desired product 164 in satisfactory results. Control experiments with the N-Me protected indolylmethanol exhibited dramatically decreased reactivity and enantioselectivity under the standard conditions, that implied this reaction proceeded via the generation of the 6-IIMs and the enantio-control relied on the double activation of CPA (Scheme 49).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 49. Asymmetric aza- and thio-1,8-addition of the 6-indolylmethanol. | |

Based on the vinylogy principle, propargylic 6-IIMs was practicable in the conjugate 1,10-addition for the construction of indole-based tetrasubstituted allenes. In 2022, the Li's group employed the propargylic 6-indolylmethanols 165 as the precursor of the extended 6-IIMs under the catalysis of CPA, which was subjected to the nucleophilic thiazolones 58 via the desired 1,10-addition process [117]. A wide variety of chiral tetrasubstituted allenes 166 bearing a quaternary stereocenter were obtained in moderate to good yields with high enantioselectivities and diastereselectivities. Subsequently, they discovered that indoles 30 were also feasible in this protocol under CPA catalysis, giving the desired products 167 in high yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 50) [118].

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 50. Asymmetric 1,10-addition of the in-situ generated propargylic 6-IIMs. | |

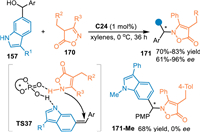

In 2022, Li and co-workers extended this 1,8-addition of in-situ generated 6-IIMs in the reaction with the isoxazol-5(4H)-ones 170 under the catalysis of C24 [119]. A N-selective stereoselective 1,8-addition was achieved, giving the target chiral indoles 171 in good yields with moderate to excellent ee values. Moreover, the N-Me protected indolylmethanol delivered the product without enantioselectivity, indicating the formation of the 6-IIMs was pivotal for the remote enantiocontrol (Scheme 51).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 51. Asymmetric 1,8-addition of the in-situ generated propargylic 6-IIMs with isoxazol-5(4H)-ones. | |

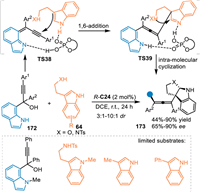

Generally, 7-indolylmethanols performed as the precursor of 7-IIMs via an elimination of a water under acid conditions, which played as a Michael acceptor to afford formal 1,4-additions [120]. Herein, propargylic 7-indolylmethanols would act as the precursor of extended 7-IIMs to undergo the 1,6-addition for the synthesis of indole-based chiral allenes. In 2023, Li and coworkers realized this protocol by using α-(7-indolyl) propargylic alcohols 172 in the reaction with tryptamines 64 under the catalysis of R-C24 [121]. The reaction was initiated by the remote 1,6-attack of the indole to the in-situ generated propargylic 7-IIMs (TS38) to generate the chiral allene species (TS39) with a dearomatized indole motif, that triggered an intramolecular cyclization to afford the enantio-enriched tetra-substituted allenes 173 in good yields with high enantio- and diastereoselectivities (Scheme 52).

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 52. Asymmetric tandem 1,6-addition and cyclization of in-situ generated propargylic 7-IIMs with tryptamines. | |

6. Summary and outlook

QMs and IIMs have proven to be as a very highly reactive and versatile species to perform nucleophilic conjugate additions, including 1,4-/1,6-/1,8-/1,10-additions, providing a convenient pathway to afford structural diversfied and valuable arene-contained structures, that really enrich the remote activation approach. The acid-promoted dehydration of hydroxybenzyl alcohols, aminobenzhydryl alcohols, and varied indolylmethanols emerged as an efficient protocol for the in-situ generation of such reactive intermediates. As a result, CPAs are demonstrated to be the most powerful tool for the in-situ generation of the QMs and IIMs, thus enabling the asymmetric conjugate additions to access structural diversified enantio-enriched structures. Intriguingly, the introduction of the alkynyl group on the abovementioned alcohols provides a facile and universal approach to access extended propargylic-QMs and -IIMs, thus allowing remote regioselective nucleophilic additions and the resulted cyclizations for the construction of structural complicated molecules. Besides, the heteroarene is likely to extend the electrophilicity of the QMs or IIMs on the heteroarene, thus inducing a remote dearomative nucleophilic additions. Despite such significant achievements connected with the remote activation have been made by the in-situ generated QMs and IIMs, there exist some apparent research gap in this field. For instance, the allylic QMs and IIMs, which feature rich synthetic potential to achieve remote conjugate addition or cycloaddition, are rarely expolred. Moreover, besides the well explored in-situ generated 2-/3-/6-/7-IIMs, the conjugate addition of 4- and 5-IIMs are still elusive, which is an important precursor to access C4 and C5 functionalized indoles. Therefore, sustained efforts shoud be paid in this field to excavate the potential of such important species.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsWe are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22001216), the Chemical Synthesis and Pollution Control Key Laboratory of Sichuan Province (No. CSPC202315), the Science and Technology Department of Sichuan Province, China (No. 2022NSFSC1203), the Higher Education Institution Key Research Project Plan of Henan Province (No. 24B150031), the Program for Youth Backbone Teacher Training in University of Henan Province (No. 2021GGJS163).

| [1] |

K. Zheng, X. Liu, X. Feng, Chem. Rev. 118 (2018) 7586-7656. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00692 |

| [2] |

S.K. Saha, A. Bera, S. Singh, et al., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 26 (2023) 99999202201470. |

| [3] |

B.E. Rossiter, N.M. Swingle, Chem. Rev. 92 (1992) 771-806. DOI:10.1021/cr00013a002 |

| [4] |

P. Wadhwa, A. Kharbanda, A. Sharma, Asian. J. Org. Chem. 7 (2018) 634-661. DOI:10.1002/ajoc.201700609 |

| [5] |

T.P. Pathak, M.S. Sigman, J. Org. Chem. 76 (2011) 9210-9215. DOI:10.1021/jo201789k |

| [6] |

N.J. Willis, C.D. Bray, Chem. Eur. J. 18 (2012) 9160-9173. DOI:10.1002/chem.201200619 |

| [7] |

Y.H. Ma, X.Y. He, Q.Q. Yang, et al., Asian J. Org. Chem. 10 (2021) 1233-1250. DOI:10.1002/ajoc.202100141 |

| [8] |

B. Yang, S. Gao, Chem. Soc. Rev. 47 (2018) 7926-7953. DOI:10.1039/C8CS00274F |

| [9] |

M. Zurro, A. Maestro, ChemCatChem 15 (2023) 99999202300500. |

| [10] |

H. Wang, S. Yang, Y. Zhang, et al., Chin. J. Org. Chem. 43 (2023) 974-999. DOI:10.6023/cjoc202211022 |

| [11] |

X. Li, Z. Li, J. Sun, Nat. Synth. 1 (2022) 426-438. DOI:10.1038/s44160-022-00072-x |

| [12] |

O. El-Sepelgy, S. Haseloff, S.K. Alamsetti, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 7923-7927. DOI:10.1002/anie.201403573 |

| [13] |

W. Guo, B. Wu, X. Zhou, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 4522-4526. DOI:10.1002/anie.201409894 |

| [14] |

W. Zhao, Z. Wang, B. Chu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 1910-1913. DOI:10.1002/anie.201405252 |

| [15] |

S. Saha, S.K. Alamsetti, C. Schneider, Chem. Commun. 51 (2015) 1461-1464. DOI:10.1039/C4CC08559K |

| [16] |

H.H. Liao, S. Miñoza, S.C. Lee, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 28 (2022) 99999202201112. |

| [17] |

A. Chatupheeraphat, H.H. Liao, S. Mader, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 4803-4807. DOI:10.1002/anie.201511179 |

| [18] |

M. Kretzschmar, T. Hodík, C. Schneider, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55 (2016) 9788-9792. DOI:10.1002/anie.201604201 |

| [19] |

H. Liao, A. Chatupheeraphat, C. Hsiao, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 15540-15544. DOI:10.1002/anie.201505981 |

| [20] |

L.Z. Li, C.S. Wang, W.F. Guo, et al., J. Org. Chem. 83 (2018) 614-623. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.7b02533 |

| [21] |

Q.Q. Yang, Q. Wang, J. An, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 19 (2013) 8401-8404. DOI:10.1002/chem.201300988 |

| [22] |

A. Lee, A. Younai, C.K. Price, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 10589-10592. DOI:10.1021/ja505880r |

| [23] |

M.R. Cerón, M. Izquierdo, N. Alegret, et al., Chem. Commun. 52 (2016) 64-67. DOI:10.1039/C5CC07416A |

| [24] |

M.Y. Hao, M.H. Huang, X.Y. Gu, et al., J. Org. Chem. 87 (2022) 1518-1525. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.1c02299 |

| [25] |

Z. Li, P.X. Zhang, Z.Z. Li, et al., Org. Lett. 24 (2022) 6863-6868. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02830 |

| [26] |

G. Singh, R. Pandey, Y.A. Pankhade, et al., Chem. Rec. 21 (2021) 4150-4173. DOI:10.1002/tcr.202100137 |

| [27] |

J.Y. Wang, W.J. Hao, S.J. Tu, et al., Org. Chem. Front. 7 (2020) 1743-1778. DOI:10.1039/D0QO00387E |

| [28] |

L. Caruana, F. Kniep, T.K. Johansen, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 15929-15932. DOI:10.1021/ja510475n |

| [29] |

W.D. Chu, L.F. Zhang, X. Bao, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52 (2013) 9229-9233. DOI:10.1002/anie.201303928 |

| [30] |

P.Z. Zi, X.B. Liu, Q.H. Zhao, et al., Green Syn. Catal. (2022). DOI:10.1016/j.gresc.2022.12.003 |

| [31] |

Z. Yue, F. Fang, Y. Xia, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 365 (2023) 1926-1933. DOI:10.1002/adsc.202300246 |

| [32] |

D. Qian, L. Wu, Z. Lin, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 567. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-00251-x |

| [33] |

L. Wang, Y. Chen, J. Xiao, Asian J. Org. Chem. 3 (2014) 1036-1052. DOI:10.1002/ajoc.201402093 |

| [34] |

A. Palmieri, M. Petrini, R.R. Shaikh, Org. Biomol. Chem. 8 (2010) 1259-1270. DOI:10.1039/B919891A |

| [35] |

G.J. Mei, F. Shi, J. Org. Chem. 82 (2017) 7695-7707. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.7b01458 |

| [36] |

A. Palmieri, M. Petrini, Chem. Rec. 16 (2016) 1353-1379. DOI:10.1002/tcr.201500291 |

| [37] |

H. Zhang, F. Shi, Chin. J. Org. Chem. 42 (2022) 3351. DOI:10.6023/cjoc202203018 |

| [38] |

M. Petrini, Adv. Synth. Catal. 362 (2020) 1214-1232. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201901245 |

| [39] |

C. Yue, F. Na, X. Fang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 11004-11008. DOI:10.1002/anie.201804330 |

| [40] |

D. Parmar, E. Sugiono, S. Raja, et al., Chem. Rev. 114 (2014) 9047-9153. DOI:10.1021/cr5001496 |

| [41] |

J.K. Cheng, S.H. Xiang, B. Tan, Acc. Chem. Res. 55 (2022) 2920-2937. DOI:10.1021/acs.accounts.2c00509 |

| [42] |

P. Wu, X.Y. Yan, S. Jiang, et al., Chem. Synth. 3 (2023) 6. DOI:10.20517/cs.2022.42 |

| [43] |

Y.W. Liu, Y.H. Chen, J.K. Cheng, et al., Chem. Synth. 3 (2023) 11. DOI:10.20517/cs.2022.46 |

| [44] |

Z. Wang, Y.F. Wong, J. Sun, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 13711-13714. DOI:10.1002/anie.201506701 |

| [45] |

Y.F. Wong, Z. Wang, J. Sun, Org. Biomol. Chem. 14 (2016) 5751-5754. DOI:10.1039/C6OB00125D |

| [46] |

J. Yan, M. Chen, H.H.Y. Sung, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 13 (2018) 2440-2444. |

| [47] |

Z. Wang, F. Ai, Z. Wang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137 (2015) 383-389. DOI:10.1021/ja510980d |

| [48] |

M. Chen, J. Sun, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 11966-11970. DOI:10.1002/anie.201706579 |

| [49] |

Y.J. Fan, L. Zhou, S. Li, Org. Chem. Front. 5 (2018) 1820-1824. DOI:10.1039/C8QO00211H |

| [50] |

M. Chen, J. Sun, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 4583-4587. DOI:10.1002/anie.201701947 |

| [51] |

F. Li, X. Chen, S. Liang, et al., Org. Chem. Front. 7 (2020) 3446-3451. DOI:10.1039/D0QO00888E |

| [52] |

T. Xiong, H. Yuan, F. Yang, et al., Green Syn. Catal. 3 (2022) 46-52. DOI:10.1016/j.gresc.2021.10.005 |

| [53] |

M. Zurro, L. Ge, S.R. Harutyunyan, Org. Lett. 24 (2022) 6686-6691. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c02786 |

| [54] |

Z. Wang, Y. Zhu, X. Pan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 3053-3057. DOI:10.1002/anie.201912739 |

| [55] |

Z. Li, Y. Li, X. Li, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 11793-11798. DOI:10.1039/D1SC03324G |

| [56] |

H.B. Hepburn, L. Dell'Amico, P. Melchiorre, Chem. Rec. 16 (2016) 1787-1806. DOI:10.1002/tcr.201600030 |

| [57] |

C. Curti, L. Battistini, A. Sartori, F. Zanardi, Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 2448-2612. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00481 |

| [58] |

G. Casiraghi, L. Battistini, C. Curti, et al., Chem. Rev. 111 (2011) 3076-3154. DOI:10.1021/cr100304n |

| [59] |

P. Zhang, Q. Huang, Y. Cheng, et al., Org. Lett. 21 (2019) 503-507. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03801 |

| [60] |

L. Zhang, Y. Han, A. Huang, et al., Org. Lett. 21 (2019) 7415-7419. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02726 |

| [61] |

M. Chen, D. Qian, J. Sun, Org. Lett. 21 (2019) 8127-8131. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b03224 |

| [62] |

J.Y. Wang, S. Zhang, X.Y. Yu, et al., Tetrahedron Chem. 1 (2022) 100007. DOI:10.1016/j.tchem.2022.100007 |

| [63] |

M. Liu, B. Shen, C. Liu, et al., Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 14562-14569. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c05107 |

| [64] |

S. Liu, K.L. Chan, Z. Lin, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 12802-12811. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c03557 |

| [65] |

J.F. Bai, L. Zhao, F. Wang, et al., Org. Lett. 22 (2020) 5439-5445. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c01812 |

| [66] |

X.Z. Zhang, Z.W. Qiu, G.H. Wen, et al., Synthesis 52 (2020) 3640-3649. DOI:10.1055/s-0040-1707348 |

| [67] |

P. Wu, L. Yu, C.H. Gao, et al., Fundament. Res. 3 (2023) 237-248. DOI:10.1016/j.fmre.2022.01.002 |

| [68] |

P. Basu, R. Sikdar, T. Kumar, et al., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2018 (2018) 5735-5743. DOI:10.1002/ejoc.201801132 |

| [69] |

J.Y. Liu, X.C. Yang, H. Lu, et al., Org. Lett. 20 (2018) 2190-2194. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.8b00503 |

| [70] |

P.H. Poulsen, K.S. Feu, B.M. Paz, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54 (2015) 8203-8207. DOI:10.1002/anie.201503370 |

| [71] |

X.Z. Zhang, B.Q. Li, Z.W. Qiu, et al., J. Org. Chem. 85 (2020) 13306-13316. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.0c01791 |

| [72] |

Z.W. Qiu, X.T. Xu, H.P. Pan, et al., Org. Chem. 86 (2021) 6075-6089. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.0c02844 |

| [73] |

Z.W. Qiu, B.Q. Li, H.F. Liu, et al., J. Org. Chem. 86 (2021) 7490-7499. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.1c00484 |

| [74] |

X. Liu, J. Zhang, L. Bai, et al., Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 671-676. DOI:10.1039/C9SC05320D |

| [75] |

W.T. Wu, L. Zhang, S.L. You, Chem. Soc. Rev. 45 (2016) 1570-1580. DOI:10.1039/C5CS00356C |

| [76] |

G. Bertuzzi, L. Lenti, D. Giorgiana Bisag, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 360 (2018) 1296-1302. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201701558 |

| [77] |

W.R. Zhu, Q. Su, H.J. Diao, et al., Org. Lett. 22 (2020) 6873-6878. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02386 |

| [78] |

W. Xiao, J. Wu, Org. Chem. Front. 9 (2022) 5053-5073. DOI:10.1039/D2QO00994C |

| [79] |

W.R. Zhu, Q. Su, X.Y. Deng, et al., Chem. Sci. 13 (2022) 170-177. DOI:10.1039/D1SC05174A |

| [80] |

Z. Wang, X. Lin, X. Chen, Org. Chem. Front. 8 (2021) 3469-3474. DOI:10.1039/D1QO00394A |

| [81] |

Y. Wu, Z. Yue, C. Qian, et al., Asian J. Org. Chem. 11 (2022) 99999202100724. |

| [82] |

T. Fu, A. Bonaparte, S.F. Martin, Tetrahedron Lett. 50 (2009) 3253-3257. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.018 |

| [83] |

X. Zhong, Y. Li, F.S. Han, Chem. Eur. J. 18 (2012) 9784-9788. DOI:10.1002/chem.201201344 |

| [84] |

S. Qi, C.Y. Liu, J.Y. Ding, et al., Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 8605. DOI:10.1039/C4CC03605K |

| [85] |

X.X. Sun, H.H. Zhang, G.H. Li, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 22 (2016) 17526-17532. DOI:10.1002/chem.201603049 |

| [86] |

M.M. Xu, H.Q. Wang, Y.J. Mao, et al., J. Org. Chem. 83 (2018) 5027-5034. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00228 |

| [87] |

Z.Q. Zhu, Y. Shen, J.X. Liu, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 1542-1545. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00351 |

| [88] |

Z.Q. Zhu, Y. Shen, X.X. Sun, et al., Adv. Syn. Catal. 358 (2016) 3797-3808. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201600931 |

| [89] |

H.H. Zhang, C.S. Wang, C. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56 (2017) 116-121. DOI:10.1002/anie.201608150 |

| [90] |

Y.Y. He, X.X. Sun, G.H. Li, et al., J. Org. Chem. 82 (2017) 2462-2471. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.6b02850 |

| [91] |

C. Hu, G. Hong, Y. He, et al., J. Org. Chem. 83 (2018) 4739-4753. DOI:10.1021/acs.joc.8b00541 |

| [92] |

T. Ikeda, T. Masuda, M. Takayama, et al., Org. Biomol. Chem. 14 (2016) 36-39. DOI:10.1039/C5OB01898F |

| [93] |

C.Y. Bian, D. Li, Q. Shi, et al., Synthesis 50 (2018) 295-302. DOI:10.1055/s-0036-1590929 |

| [94] |

Y. Mao, Y. Lu, T. Li, et al., Chin. J. Org. Chem. 40 (2020) 3895. DOI:10.6023/cjoc202005096 |

| [95] |

X. Huang, Y.I. Jeong, B.K. Moon, et al., Langmuir 29 (2013) 3223-3233. DOI:10.1021/la305069e |

| [96] |

M.R. Franklin, Biochem. Pharmacol. 46 (1993) 683-689. |

| [97] |

F. Bonardi, E. Halza, M. Walko, et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108 (2011) 7775-7780. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1101705108 |

| [98] |

X. Li, M. Duan, Z. Deng, et al., Nat. Catal. 3 (2020) 1010-1019. DOI:10.1038/s41929-020-00535-4 |

| [99] |

X. Li, J. Sun, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 17049-17054. DOI:10.1002/anie.202006137 |

| [100] |

B.X. Xiao, R.J. Yan, X.Y. Gao, et al., Org. Lett. 19 (2017) 4652-4655. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b02287 |

| [101] |

B.X. Xiao, X.Y. Gao, W. Du, et al., Chem. Eur. J. 25 (2019) 1607-1613. DOI:10.1002/chem.201803592 |

| [102] |

X.L. He, H.R. Zhao, C.Q. Duan, et al., Org. Lett. 20 (2018) 804-807. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03942 |

| [103] |

J.L. Li, C.Z. Yue, P.Q. Chen, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53 (2014) 5449-5452. DOI:10.1002/anie.201403082 |

| [104] |

X. Li, M. Duan, P. Yu, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 4881. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-25165-7 |

| [105] |

K. Bera, C. Schneider, Chem. Eur. J. 22 (2016) 7074-7078. DOI:10.1002/chem.201601020 |

| [106] |

K. Bera, C. Schneider, Org. Lett. 18 (2016) 5660-5663. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02898 |

| [107] |

F. Göricke, C. Schneider, Org. Lett. 22 (2020) 6101-6106. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02166 |

| [108] |

G. Mehta, S. Muthusamy, Tetrahedron 58 (2002) 9477-9504. DOI:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)01187-0 |

| [109] |

A. Ford, H. Miel, A. Ring, et al., Chem. Rev. 115 (2015) 9981-10080. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00121 |

| [110] |

H.J. Loui, A. Suneja, C. Schneider, Org. Lett. 23 (2021) 2578-2583. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.1c00489 |

| [111] |

J. Adrio, J.C. Carretero, Chem. Commun. 47 (2011) 6784-6794. DOI:10.1039/c1cc10779h |

| [112] |

R. Narayan, M. Potowski, Z.J. Jia, et al., Acc. Chem. Res. 47 (2014) 1296-1310. DOI:10.1021/ar400286b |

| [113] |

S.V. Kumar, P.J. Guiry, Chem. Eur. J. 29 (2023) 99999202300296. |

| [114] |

X.X. Sun, C. Li, Y.Y. He, et al., Adv. Synth. Catal. 359 (2017) 2660-2670. DOI:10.1002/adsc.201700203 |

| [115] |

C. Li, H. Lu, X.X. Sun, et al., Org. Biomol. Chem. 15 (2017) 4794-4797. DOI:10.1039/C7OB01059A |

| [116] |

Q. Song, P. Zhang, S. Liang, et al., Org. Lett. 22 (2020) 7859-7863. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02769 |

| [117] |