b Institute of Fundamental and Frontier Sciences, University of Electronic Science and Technology of China, Chengdu 611731, China;

c Suzhou Industrial Technology Research Institute of Zhejiang University, Zhejiang University, Suzhou 215159, China

Electrochemical CO2 reduction (ECR) into chemicals and fuels with clean and renewable electronic energy can not only reduce CO2 emissions but also produce more valuable products, which is of great significance to clean energy conversion and net carbon emission reduction [1–3]. As a complex reaction process with multi-proton coupled electron transfer, developing efficient electrocatalysts plays a crucial role in the advancement of ECR [4]. Although various metal and their nanoparticles show certain ECR abilities, they inevitably suffer from the issue of high reaction over-potential [5,6]. As the CO2 molecule is linear and centrosymmetric with two oxygen-carbon (C=O) bonds, the energy required to dissociate a C=O bond is about 800 kJ/mol, thus making the CO2 molecule difficult to be activated in electrocatalysis with a quite negative potential of −1.9 V vs. SHE (25 ℃, pH 7) [7]. Therefore, highly efficient catalysts are urgently needed for ECR.

In recent years, single-atom catalysts (SACs) have emerged as a promising class of catalysts for ECR with efficient CO2 activation properties [8–10]. Benefiting from the unsaturated coordination environment and unique structure of single-atom sites, SACs exhibit impressive ECR performance with theoretically nearly 100% atom utilization [11]. As the research progressed, many researchers further tuned the ECR performance of SACs with various strategies, such as regulating the coordination number of the metal atoms [12–14], changing the coordinated non-metal atoms [15], introducing axial non-metal atom coordination [16], modifying the substrate of single-atom sites [17,18], etc. However, it is considered rather tricky to simultaneously optimize multiple reaction barriers of various intermediates for one monotonous single-atom configuration during the complex ECR process [19,20]. Further improving the ECR performance by boosting the intrinsic activity of such atomically dispersed metal sites still remains challenging.

It is well known that the adjacent metal atoms may trigger synergistic effects in catalytic reactions [21–24]. Inspired by this strategy, diatomic-site catalysts (DASCs) with adjacent atoms are constructed as an extension of SACs [25,26]. DASCs have received great attention due to their unique configuration. First, the metal atoms in the DASC are atomically dispersed, allowing the maximum utilization of metal atoms. Secondly, distinguished from the dual active site catalysts with two individual-worked single-atom sites, the interaction of the adjacent atoms provide sophisticated strategies to modulate both the geometric structure and electronic configuration for DACSs, thus endowing them new properties [27–31]. As a new research frontier, there have been numerous reports on using DASCs for ECR, achieving remarkable experimental breakthroughs. Several reviews on the synthesis, electrochemical applications, and working mechanisms of DASCs have been reported [32–34]. However, the development of DASCs still poses multiple challenges, including precise synthesis and accurate characterization, reasonable activity evaluation, and insight into the ECR mechanism on diatomic sites. In-depth discussions of these challenges can contribute to the development of DASCs, thereby achieving better performance in ECR.

In this review, we summarized the recent progress in ECR on heterogeneous DASCs. The DASCs have been first systematically classified, distinguished from the simple mixed strategy of single-atom sites. And the challenges in precisely preparing and characterizing such DASCs have been emphasized. Then the advanced ECR performances on DASCs are highlighted with inter-metal interaction and the synergistic effects of the adjacent metal atoms in comparison of SACs. On this basis, the origin of the advanced ECR performances on the DASCs is comprehensively summarized, which is very important to guide the future efficient catalyst design for ECR. Finally, the opportunities and challenges are proposed to shed light on the development of DASCs for ECR application.

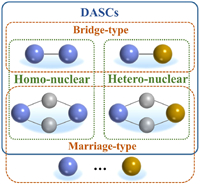

2. Classification and challenges in preparation and characterization of heterogeneous DASCs 2.1. ClassificationAt present, most of the reported heterogeneous DASCs for electrocatalysis are prepared by anchoring metal atoms on hetero-atom doped carbon materials, a few DASCs are synthesized based on the other substrates, such as black phosphorus, Pd-Te alloy nanowires, TiO2, and CeO2 [20,35–37]. This is because such carbon-based materials not only provide favorable anchoring sites to stabilize the isolated metal atoms, but also offer good chemical stability and excellent electrical conductance with graphitic frameworks [38–40]. Based on the species of metal atoms, the DASCs can be classified as homo-nuclear and hetero-nuclear diatomic sites. Meanwhile, according to the spatial distribution and metal-metal bonds, the DASCs will be classified as bridge-type sites with metal-metal bonds and marriage-type sites without direct metal-metal bonds (Fig. 1). For the bridge-type DASCs, the two metal atoms bonded with non-metal atoms and formed a direct metal-metal bond. For example, Ren et al. prepared a carbon-anchored DASC with isolated diatomic Ni-Fe metal-nitrogen sites for ECR, where the neighboring Ni-Fe center was configured with six nitrogen atoms of the nitrogen-doped carbon and underwent a structural change into a CO-adsorbed moiety upon CO2 uptake [41]. In the DASCs with marriage-type diatomic sites, the two metal atoms may not be directly connected by a metallic bond. They may share one or more coordinated non-metallic atoms to modulate the charge population of both metal atoms, which is distinguished from the single-atom metal sites. Ding et al. reported a nitrogen-doped carbon anchored uniform atomically precise Ni2 site, which consisted of two Ni-N4 moieties shared with two nitrogen atoms as a Ni-N6 site [42]. Note that the dual atoms should be accounted as a single active site, and the distance between the two metal atoms needs to keep within a specific range. Therefore, some mixed single-atom metal catalysts, cannot be defined as DASCs in a strict sense because most of the two metal atoms work individually.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Schematic of classification for DASCs. | |

A universal method to fabricate heterogeneous DASCs is to carbonize nitrogen-contained precursors with metal dopants, as the generated nitrogen-carbon framework provides favorable sites to anchor the metal atoms. A typical approach therein is employing hetero-metal doped zeolitic imidazolate framework 8 (ZIF-8) as the template precursor, which is also a widely used method to synthesize SACs [43,44]. During the pyrolysis process, Zn would be evaporated away and the doped metal ion would be reduced as atomically dispersed atoms anchored on the porous carbon. Based on this approach of ZIF-8 carbonization, two technical routes are presented for the preparation of DASCs. One is to simultaneously introduce the target metal atoms into the precursor followed by the carbonization process. For example, Cheng et al. simultaneously introduced Ni(acac)2 and Cu(OAc)2·H2O to the synthesis process of ZIF-8 to form Ni/Cu-ZIF-8. Following the 1100 ℃ carbonization under Ar atmosphere, a hetero-nuclear marriage-type diatomic Ni-Cu-N-C catalyst was declared to obtain [45]. However, it still remains ambiguous how these hetero-nuclear diatomic sites form priority to the homo-nuclear Ni-Ni sites or Cu-Cu sites. In the fabrication of homo-nuclear DASCs, this issue will be avoided particularly with ingenious metal dopants. Ye et al. introduced Fe2(CO)9 with an initial Fe-Fe bond as the iron source during the ZIF-8 synthesis to form a Fe2(CO)9@ZIF-8 hybrid structure, where the iron compound could be caged and separated by the cavity of ZIF-8. After a subsequent pyrolysis treatment, the Fe2 cluster can be anchored on the N-doped carbon to form a homo-nuclear Fe2-N6 site with a direct Fe-Fe bond. The coordination number of Fe-N(O) bond and Fe-Fe bond were 4.3 and 1.2 in this DASC calculated by fitting the results of EXAFS, respectively, indicating the precise diatomic sites [46]. Similarly, Ding et al. employed a Ni(dppm)2Cl dinuclear cluster as Ni source during the hybrid ZIF-8 synthesis, and a DASC with marriage-type homo-nuclear diatomic Ni sites was obtained [42]. Different from the above one-step route to obtain hybrid ZIF-8 samples, Ren and co-authors reported an ion-exchange strategy to obtain Fe and Ni co-doped ZIF-8, where Fe doped ZIF-8 was first prepared with Fe ions chemically bonded to the organic ligand as nodes, and Ni ion subsequently encapsulated within the small ZIF-8 cavities by a two solvent route [41]. After 1000 ℃ pyrolysis, a DASC with a direct Ni-Fe bond was fabricated.

Although the route of using ZIF-8 as the basic precursor to fabricate these catalysts exhibits several advantages of uniform morphology and abundant micro-pore structure, some drawbacks should be noted, such as the low yield rate of final samples and the inevitable residue of a trace amount of Zn atoms in catalyst, which may hinder the further application and influence the catalytic performance [47,48]. Beyond using ZIF-8 as the precursor, Zeng et al. pyrolyzed L-alanine (amino acid), ferric acetate, nickel acetate tetrahydrate and melamine together at 900 ℃ under Ar atmosphere, after etching by HCl to remove the metal nanoparticles, a DASC catalyst with marriage-type Fe and Ni sites as declared [49]. Lu et al. reported a sol-gel method to prepare Zn/Co bimetallic sites using chitosan as C and N sources. It is worth noting that the quality of the diatomic sites are severely affected by the synthesis conditions, and single-atom Zn sites and Co sites inevitably co-exist in the final products [50].

Besides these approaches of metal-contained precursor carbonization, other techniques have also been reported to be available to prepare DASCs. For example, Liu et al. have successfully assembled a kind of Pt-Ru DASC with atomic layer deposition (ALD) method, where the Pt atoms were first deposited on carbon nanotubes by ALD method and then selectively deposited Ru atoms on Pt atoms by optimizing the ALD experimental parameters [51]. Chen and co-authors reported a simple method of solventless ball milling to prepare a homo-nuclear Ni2/N-C DASC, that a dinuclear nickel cryptate was used as the Ni source and mixed with carbon black by ball milling. But high-temperature pyrolysis at 873 K under a nitrogen atmosphere is still needed to transform the organic compounds into electroconductive nitrogen-doped carbon to obtain the final DASC [52].

Consequently, most of the reported synthesis routes for DASCs are similar to that of the SACs, several different combinations of diatomic sites more than the single-atom sites may coexist in the catalyst. Accurate synthesis of the diatomic configurations for DASCs still remains challenging. Therefore, advanced techniques for DASCs synthesis are still urgently needed, as well as more explorations need to be done to reveal the formation mechanism of diatomic metal sites.

2.3. Challenges in the characterization of heterogeneous DASCsSince DASCs possess the fundamental attributes of atomically dispersed metal catalysts, most of the characterization methods of SACs are suitable to characterize DASCs. High-angle annular dark-field imaging on spherical aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscope (HAADF-STEM) and X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements could observe the existence and coordination of the atomic dispersed sites. Nevertheless, due to the complexity of diatomic sites, more attention should be paid to revealing the accurate configuration for both metal atoms, which brings more challenges for the characterizations of diatomic sites and differs from that of SACs. The diatomic metal sites can be directly visualized as bright dot pairs on the carbon substrate in the HAADF-STEM images. As illustrated in Zhao's work, the bright dots of Fe atoms mainly exist in pairs on the HAADF-STEM image of the prepared diatomic Fe catalyst, and the distances between the neighboring two dots are less than 2.6 Å, which is quite a short distance to form direct metal-metal bonds, preliminarily implicating the existence of diatomic Fe-Fe sites (Fig. 2a) [53]. On the contrary, a distance of 5.0 Å for the neighboring metal atoms in a Fe and Cu dual-atom catalyst demonstrates the absence of Fe-Cu bond, implying the individual Fe-Nx and Cu-Nx sites in the sample (Fig. 2b) [54]. Obviously, it is not sufficient to determine whether such atomically dispersed metal sites are diatomic sites only by HAADF-STEM images, as the observed distance between the neighboring metal atoms in the 2D image may be affected by the spatial distribution of metal atoms in 3D catalyst powders. Moreover, since the metal atoms are all bright dots in the image, it is impractical to distinguish the elements for the metal sites for hetero-nuclear DASCs.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) HAADF-STEM image and the distance in the observed atomic pairs for Fe2NPC. Copied with permission [53]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (b) HAADF-STEM image and the distance in the observed atomic pairs for FeCu-DA/NC. Copied with permission [54]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry. (c-e) Fe K edge XANES, FT EXAFS spectra and FT EXAFS fitting spectrum at R space for Fe2@PDA-ZIF-900. Copied with permission [59]. Copyright 2022, John Wiley & Sons. FT-EXAFS spectra at (f) Fe K-edge, (g) Co K-edge and (h) schematic for FeCo-N/C. Copied with permission [60]. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. | |

In contrast to HAADF-STEM tests only offer information on the specific localized area, XAFS tests can afford comprehensive insights concerning the overall structure [55]. XAFS refers to the oscillatory structure in the X-ray absorption coefficient just above an X-ray absorption edge, which can provide the detailed atomic structure as well as vibrational and electronic properties of the given material for a certain metal element. Therefore, XAFS is a powerful tool for investigating the local coordination environment of the anchored metal atoms [56–58]. For instance, the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra of Fe2@PDA-ZIF-900 located between Fe foil and FeO, demonstrating the oxidation state of Fe in the catalyst situated between 0 and +2 (Fig. 2c). The atomic structures of the Fe sites were investigated by the Fourier-Transform (FT) of the EXAFS spectra in R-space at the Fe-K-edge, where the first dominant peak of the catalyst resembles FePc at 1.41 Å is attributed to the Fe-N coordination, and a secondary peak at 2.20 Å was assigned to Fe-Fe bonds (Fig. 2d). By fitting the R-space curve with density functional theory (DFT) models, the diatomic Fe-Fe sites with Fe2N6 configuration were finally revealed for the Fe2@PDA-ZIF-900 catalyst (Fig. 2e) [59].Compared to homo-nuclear DASCs, hetero-nuclear DASCs are more complex since three distinct diatomic configurations (i.e., M1-M1, M1-M2, M2-M2) may co-exist in the substrate plane. Benefiting from the good sensitivity of XAFS for distinguishing the metal-metal bonds in length, the FT spectrum in R-space will provide clear criteria for investigating the hetero-nuclear diatomic sites. For instance, except for the first dominant peak of metal-N at about 1.5 Å in the FT spectra of FeCo-N/C at Fe K-edge and Co K-edge, a secondary peak of the DASC located at about 2.2 Å, which is similar but distinguished from both the Fe-Fe bond in Fe foil and Co-Co bond in Co foil, either the metal-oxygen bond, implying the existence of Fe-Co bond in FeCo-N/C (Figs. 2f and g). By fitting these R-space curves, the average coordination numbers of Fe-N, Co-N, and Fe-Co in the catalyst are calculated to 3, 3, and 1, respectively. Based on these results, the author raised the hetero-nuclear diatomic configuration of FeN3-CoN3 with direct Fe-Co bonds for the catalyst (Fig. 2h) [60]. Although XAFS is widely used and achieved satisfactory results in the characterization of diatomic sites, several issues still need to be reminded: (1) The obtained data represents the average value within the test range, which may be influenced by the potential nanocluster and single-atom sites, especially for homo-nuclear DASCs. This phenomenon will lead the evaluated coordination numbers for metal-N bond and metal-metal bond not an integer; (2) It is difficult to well fit the second shell of the metal atoms, thus making it difficult to reveal the configuration of atomic metal sites in a larger range, especially for the marriage-type DASCs, thus bring some deviation in constructing the diatomic site model for further DFT simulations.

Mössbauer spectroscopy is another powerful technique for characterizing Fe and Sn-based materials, which can be used to study the hyperfine interaction between the nucleus and the surrounding environment for DASCs. For instance, Ding et al. employed 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy to validate the electronic states of the N-coordinated Fe in the hetero-nuclear Fe1-Mo1 dual-metal catalytic pair on ordered porous carbon. The line width of the Mössbauer spectrum for the DASC is significantly decreased as compared to the single-atom Fe1-NC sample. In the further quantitative analysis, the spectrum for the DASC can be deconvoluted into Fe4+ (94.9%) and high-spin Fe3+ (5.1%), while the spectrum for the SAC can be split into high-spin Fe2+ (44.6%) and high-spin Fe3+ (66.4%). These different results evidently illustrate the chemical states of Fe and Mo in the DASC are influenced by the electronic interaction between them, providing powerful evidence for the existence of the diatomic sites [31].

3. ECR performance and mechanism on heterogeneous DASCs 3.1. General overview of ECR performances on heterogeneous DASCsIn the past decades, SACs have been widely investigated for ECR with experiments and DFT simulations, finding that the inherent scaling relations between the adsorption energies of intermediates seriously restrict the catalytic performance of ECR [61–63]. The construction of heterogeneous DASCs provides a promising candidate to break such scaling relations for efficient ECR. Since the related experimental exploration of DASCs is still developing, the theoretical free energy calculations can be used to simulate the ECR process on DASCs, thus providing an efficient approach to screen highly efficient DASC candidates for ECR. At present, there have been a number of reports about predicting the ECR performance of various diatomic configurations. For instance, Li et al. used large-scale screening-based DFT and microkinetics modeling to investigate the ECR performance of some transition metal dimers supported on graphene with adjacent single vacancies. By comparing the adsorption behavior of COOH, CHO, and H intermediates with CO on the diatomic model, they found which allows for the possibility of reducing the over-potential of the adsorption of COOH and CHO was enhanced with respect to that of CO, superior to the case on packed (111) metal surface, CO2 protonation on most of the metal dimers (Figs. 3a and b) [64]. Luo et al. constructed a series of DASC models by embedding a TM1/TM2-N6 (TM represents transition metal) sites into a rectangle superlattice of graphene. By computing the adsorption free energy of CO* intermediate, 8 of the 9 DASCs showed free energy values higher than −0.2 eV, except for the Ni/Ni sample, indicating the CO* can easily desorb to form CO product on the 8 kinds of DASCs (Figs. 3c and d). Further, by using the adsorption strength of OH* and COOH* species as an indicator, the authors found that the scaling relationship between the adsorption strength of COOH* and CO* species had been broken in the case of Cu/Mn, Ni/Mn and Ni/Fe, leading to a good ECR activity for these samples [65]. An and co-authors investigated the synergy of a NiCo dimer anchored on a C2N graphene matrix for ECR by means of DFT and computational hydrogen electrode methods. The calculation results demonstrate that NiCo site exhibits more advantaged ECR properties to hydrogen evolution in free energy (Fig. 3e), and the diatomic sites would not deactivate by the strongly-bound intermediates under the case of viable co-adsorbates [66]. Ouyang et al. screened 21 kinds of hetero-nuclear transition metal dimers embedded in monolayer C2N as potential DASC for ECR (Fig. 3f) [67]. By adjusting the components of dimers, the two metal atoms play the role of carbon adsorption sites and oxygen adsorption sites, leading to the decoupling of adsorption energies of key intermediates. Cu/Cr and Cu/Mn dimers are identified as promising candidates for ECR to CH4 with limiting potentials of −0.37 V and −0.32 V, respectively (Fig. 3g). Moreover, the stability of the C2N-supported metal dimers is also considered in Wang's work, by analyzing the energy difference (△Eb) between the adsorption energy of metal dimers on C2N substrate and the cohesive energy of metal atoms in crystals. The results indicate most of the metal dimers may aggregate into clusters (Fig. 3h), hinting a potential crisis of DASCs.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Schematics for MN@2SV structures, (b) screening of CO2 electroreduction intermediate (CO, COOH, CHO, H, O, and OH) adsorption with respect to CO on different MN@2SV. Copied with permission [64]. Copyright 2015, American Chemical Society. (c) Schematic geometric structure of TM1/TM2–N6–C DMSCs, (d) adsorption free energy of COOH* (DGCOOH*) and CO* (DGCO*) on 9 DMSCs. Copied with permission [65]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry. (e) Difference in limiting potentials for the CO2RR and HER on the NiCo@C2N and the other sites. Copied with permission [66]. Copyright 2019, American Chemical Society. (f) Design concept of monolayer C2N supported heteronuclear transition-metal dimers. (g) Free energy diagram of the CO2 reduction pathway toward CH4 on CuCr/C2N and CuMn/C2N at different applied potentials. (h) Energy difference between adsorption energy of TM atoms on C2N and the cohesive energy of TM atoms. Copied with permission [67]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry. | |

Although many computer simulations provide useful guidelines for further developing efficient DASCs for ECR, it is notable that the model of constructed diatomic sites in the simulation is still a simplification of the real catalyst. It is difficult to fully reflect the catalytic properties of the real catalyst. In addition, the actual electrocatalytic reaction on electrodes is a very complex process, which includes electrostatic potential, transient state, solvation effect, electrical double layer, mass transfer and other factors, thus leading the simulation of real electrocatalytic reaction process to be a challenge and frontier topic in computational electro-chemistry.

3.2. Experimental ECR performance on heterogeneous DASCsThe application of DASCs in ECR is now in a rapid development stage, various DASCs have been reported for ECR investigations. However, unlike the theoretical simulations with many kinds of DASC models, most of the experimental DASCs reported for ECR are constructed by anchoring metal dimers on nitrogen-doped carbon substrates. The main reason for this issue may be attributed to the fact that such carbon frameworks provide favorable sites to stabilize the metal atoms [68]. At present, most of the reported metal atoms in DASCs for ECR are Ni, Fe, Co and Cu, involving homo-nuclear and hetero-nuclear DASCs with the metal-metal bond or marriage-type configurations. As expected, these DASCs exhibit remarkable ECR performance, superior to the corresponding SACs. For instance, in Zhao's work [53], a homo-nuclear Fe DASC with Fe-Fe bonded Fe2N6 configuration sites (Fe2NPC) was precisely prepared for ECR (Fig. 4a). The Fe2NPC achieved CO Faradic efficiency (FECO) up to 96.0% at −0.6 V (vs. RHE), which was superior to the maximum FECO of 83.5% on the corresponding single-atom Fe catalyst (Fe1NPC) prepared with different iron precursor (Fig. 4b). The turnover frequency number of Fe atoms for the Fe2NPC was 1.8 times higher than that of the Fe1NPC (Fig. 4c), demonstrating that the iron atoms in the DASC were more active for ECR. This point was further confirmed by the measurements of Tafel plots, as Fe2NPC achieved a Tafel slope of only 60 mV/dec, lower than that of 78 mV/dec for Fe1NPC (Fig. 4d). Liang et al. reported a homo-nuclear Ni2 DASC named Ni2-NCNT for ECR (Fig. 4e) [69]. By poisoning the metal sites with SCN−, the atomically dispersed Ni sites were considered to be the primary ECR active sites for both Ni2-NCNT and the single-atom Ni1-NCNT catalyst. The maximum FECO for the Ni2-NCNT was 97%, in contrast to the FECO of 89% for Ni1-NCNT at −0.9 V vs. RHE (Fig. 4f). The difference in ECR performance for the DASC and SAC was further pronounced in the comparison of CO-producing current density (jCO), where the Ni2-NCNT achieved jCO of 76.2 mA/cm2 at −1.4 V vs. RHE without iR correction, much higher than that of 32.7 mA/cm2 for Ni1-NCNT (Fig. 4g). And after the analyzation of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and electrochemical active surface area (ECSA), the mass activity of nickel was further investigated, where the jCO mass activity of the Ni2-NCNT is 2.3-times higher than that of the Ni1-NCNT, confirming the enhanced ECR performance of the DASC originated from the unique diatomic metal site rather than the different Ni loading (Fig. 4h).

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. (a) Schematic of ECR on Fe2NPC. (b) FECO, (c) TOF number, (d) Tafel plots of Fe2NPC on the contrary of Fe1NPC. Copied with permission [53]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (e) Schematic of Ni2-NCNT DAC. (f) FECO, (g) jCO, (h) the specific current densities of CO normalized by the mass of Ni for Ni2-NCNT. Copied with permission [69]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V. (i) Least-squares curve-fitting analysis of operando EXAFS spectra at the Ni K-edge for Ni2/NC. (j) Comparison between the Ni K-edge XANES experimental spectra (solid lines) and the theoretical spectra (dashed lines) calculated with the depicted structures (insert). Copied with permission [42]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. | |

Similar ECR performances are also obtained on many other DASCs, involving the hetero-nuclear DASCs and the marriage-type DASCs as well. For instance, Ren et al. reported a bridge-type Ni-Fe DASC (Ni/Fe-N-C) with metal atoms anchored on nitrogen-doped porous carbon for ECR. The obtained Ni/Fe-N-C outperformed the corresponding single-atom catalysts of Fe-N-C and Ni-N-C across the entire potential window from −0.4 V to −1.0 V, reaching a maximum FECO of 98% at −0.7 V vs. RHE. And Ni/Fe-N-C achieved jCO of 7.4 mA/cm2 at −0.7 V vs. RHE in 0.5 mol/L KHCO3, which is 1.5 and 4.6 times higher than that of Ni-N-C and Fe-N-C catalysts, respectively. Moreover, the Tafel slope of ECR on Ni/Fe-N-C decreased to 96 mV/dec, lower than that of 101 mV/dec for Fe-N-C and 143 mV/dec for Ni-N-C, demonstrating the rate-determining step of the first electron transfer to generate *COOH was greatly enhanced on the DASC [41]. Li and co-workers reported a marriage-type homo-nuclear Ni DASC (Ni2/NC) for ECR, which consists of two Ni1-N4 moieties shared with two nitrogen atoms, anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon. Besides demonstrating the superior ECR performance of the DASC to the single-atom Ni catalyst, the authors employed operando synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy to investigate the diatomic site, revealing that an oxygen-bridge adsorption on the Ni2-N6 site to form an O-Ni2-N6 structure with enhanced Ni-Ni interaction (Figs. 4i and j) [42].

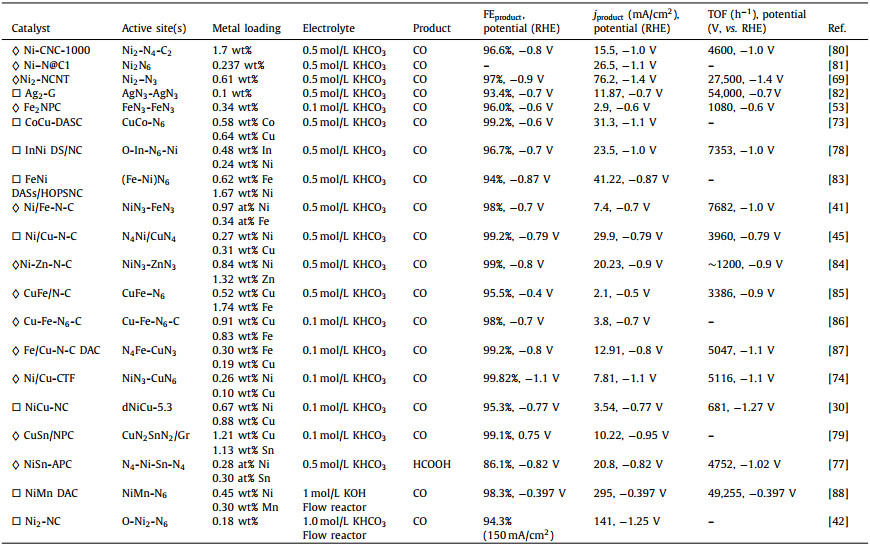

In terms of ECR products, the reported DASCs mainly produce CO via ECR at present, which is quite different from the SACs. The main reason could be attributed to two aspects, one is that the interactions between the two metal atoms lead to a weak *CO bond energy on the diatomic sites to facilitate CO desorption, and the other one is that the diatomic sites favor to bond the C atom of CO2 molecular to avoid the pathway of HCOOH generation. For instance, single-atom Cu catalysts have been reported several times for ECR, which produce various kinds of reduction products beyond CO, such as CH3OH, CH4, C2H5OH and acetone [70–72]. On the contrary, to date, the reported Cu-contained DASCs only produce CO via ECR [73,74]. The single-atom In catalyst with In-N4 sites and the single-atom Sn catalyst with Snδ+ on N-doped graphene have been reported to electrochemically reduce CO2 to HCOOH with high efficiency [75,76]. But when the In atom and Sn atom couple with other transition metal atoms to form diatomic sites, only few of these obtained DASCs will reduce CO2 to HCOOH, and most of the DASCs may produce CO as the main product instead of HCOOH [77–79]. Not to mention the DASCs constructed with CO-product favorable metal atoms. In order to comprehensively analyze and compare, we summarized the recent ECR performance on DASCs in Table 1 [30,41,42,45,53,69,73,74,77–88].

|

|

Table 1 Summary of ECR performance for experimental available DASCs (◇bridge-type, ⬜ marriage-type). |

By summarizing these results, it could be observed that DASCs have shown excellent ECR activity and CO generation property superior to the SACs. It is worth noting that most of the DASCs reported for ECR so far are based on nitrogen-doped carbon substrates, more experimental research models are still urgently needed to be developed for ECR. In addition, although many studies have declared that DASCs remain stable in long- time electrochemical reactions, only a few reports focus on the real-time evolution of the diatomic sites in the ECR reaction process. Since it is well known that the metal atoms in single-atom metal sites may suffer dynamic evolution during the electrocatalytic reaction [89–91], more deep insights into the real reaction sites or inactivation of DASCs remain to be further revealed. And more reaction conditions, as well as the flow-cell reaction systems beyond the H-cell reactor, remain to be further carried out for ECR studies on DASCs.

3.3. Reaction mechanismGenerally, the metal atoms anchored on carbon-based substrates are undoubtedly identified as the active centers for ECR. To investigate the reaction pathway for ECR, in-situ Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is broadly employed to verify the reactive intermediates, such as *HCO3, *COOH and *CO [92,93]. But it is still very difficult to analyze the interaction between these intermediates and the diatomic metal sites. DFT calculations can simulate the electrocatalytic reaction with free energies of reactants, leading it the most powerful approach to investigate the reaction mechanism of ECR on DASCs, where the catalyst model and reaction intermediates are constructed based on the material characterization and the results of in-situ spectroscopy measurements.

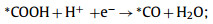

So far, CO and HCOOH are the main ECR products on DASCs, which only suffer two-electron transfer processes. Since the CO product is more common in the present experimental reports and suffered more complex reaction steps than the generation of HCOOH, we mainly focus on the mechanism of CO2 reducing to CO in this work. The overall conversion process is usually proposed to occur in four steps (where * represents adsorption sites) [94–97]:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Sometimes Steps 1 and 2 may also be considered as one step noted as CO2 + * + H+ + e− → *COOH [15,98]. It is obvious that the catalysts require to provide enough affinity to bind the CO2 molecule and facilitate the activation of CO2 for the reaction course of CO2 to CO conversion. And the binding strength of *COOH intermediate should be strong enough for further reduction. Meanwhile, with the aim of efficient CO production, catalysts should provide a weak *CO binding strength to facilitate CO desorption from the surface. However, the binding energies of *COOH and *CO are typically proportionally correlated via the so-called scaling relations, making them challenging to be tuned individually [99]. In contrast to the SACs with only one type of isolated active site, the diatomic metal pair will provide more possibility to simultaneously adjust the binding strength of intermediates for the multi-intermediate ECR process to generate CO. At present, the advanced CO2-to-CO conversion performances on DASCs are mainly achieved by enhancing CO2 activation and facilitating CO desorption through the synergistic effects of the two metal atoms. To clearly summarize the recent studies on the electrochemical CO2-to-CO reaction mechanism, the DASCs could be briefly divided into two aspects: (1) the DASCs constructed with Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn and so on, whose corresponding single-atom M-Nx sites are known for favorable CO production; (2) the DASCs constructed with Cu, In, Sn and so on, whose corresponding single-atom sites could produce other products expect for CO [100–102].

3.3.1. ECR mechanism on heterogeneous DASCs constructed by Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, and ZnAs mentioned above, CO2 activation and CO desorption are considered pivotal steps for CO2-to-CO conversion. According to the previous studies of ECR on atomically dispersed transition metals anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon, single-atom Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, and Zn sites are known to achieve impressive activity and selectivity for CO production [103]. Typically, the single-atom Ni-N sites, for example Ni-N4 site, exhibit high current density for CO production but still suffer from sluggish kinetics of the CO2 activation process [104]. Fe-N sites, Mn-N sites and Co-N sites usually show low free energy barrier for CO2 activation, whereas the desorption of *CO hindered their reactivity of CO producing with over-strong *CO binding strength on the Fe, Mn or Co atoms [105]. Han et al. reported a marriage-type N-bridged Ni and Mn DASC (NiMn DASC) for ECR, where the synergistic electronic modification effect caused by coupling neighboring Ni and Mn atoms was highlighted by the authors. By employing DOS and Bader charge analysis, it is found that electron interaction occurred between the neighboring Ni and Mn atoms, as more charge accumulated at the Ni atom and the electron density near the Fermi level of NiMn DASC was obviously tuned compared to the corresponding SACs. As a result, the NiMn DASC exhibited significantly lower free energy barriers in the step of *COOH generation than Ni SAC and in the step of *CO desorption than Mn SAC, leading to highly efficient CO production for the NiMn DASC (Fig. 5a) [106]. Li et al. investigated the synergistic effect of bridge-type Ni-Zn diatomic sites for enhanced ECR to CO production. The in-situ characterizations combined with DFT simulations demonstrated that the Ni-Zn coordination modified the d-state of the metal atom, narrowing the gap between the d-band center of the Ni 3d orbitals and the Fermi energy level to strengthen the electronic interaction at the reaction interface. In this sense, lower free energy barriers for CO2 activation and *CO desorption were achieved on the DASC, superior to the single-atom Ni and Zn catalysts [84].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 5. (a) Free energy diagrams for ECR to CO production on NiMn DASC. Copied with permission [88]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V. (b) The catalytic mechanism on Fe/Ni-N-C based on the optimized structures of adsorbed intermediates COOH* and CO*. (c) Free energy diagrams for ECR on Fe/Ni-N-C. Copied with permission [41]. Copyright 2019, John Wiley & Sons. (d) Free energy diagrams of ECR on the Fe2N6 site. Copied with permission [53]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (e) The PDOS of Ni/Cu-CTF before and after CO2 absorption. (f) Free energy diagrams for ECR on Ni/Cu-CTF. Copied with permission [74]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier B.V. (g) Configuration of CO2 adsorption on CuN2SnN2/Gr, (h) selectivity between ECR and HER (UL(CO2)-UL(H2)) on CuN2SnN2/Gr, CuN3/Gr, and SnN3/Gr. Copied with permission [79]. Copyright 2023, Tsinghua University Press. | |

Besides tuning the electronic state of the metal sites, the synergistic effect of the metal-metal pair may also provide other possible energy-optimized reaction pathways of CO2-to-CO conversion. Taking a bridge-type Fe-Ni DASC for instance, by constructing the Fe-Ni diatomic sites, the advantages of the atomic Ni site and Fe site were successfully combined, achieving higher ECR performance for CO production on the DASC than on the corresponding SACs. DFT simulations revealed that the carbon atom and one oxygen atom of *COOH intermediate were bonded by the Ni atom and Fe atom of the diatomic site, respectively. Even though the diatomic Fe-Ni site tended to be passivated with a strong *CO binding strength, the CO-adsorbed Fe-Ni moiety could provide an additional site for the second CO2 activation to form *CO and *COOH co-adsorption on the diatomic site (Fig. 5b). In this way, the binding strength of *COOH and *CO on the CO-adsorbed Fe-Ni diatomic moiety were weaker than on bare single-atom Ni or Fe sites, which increased the free energy barrier of CO2 to *COOH to 0.47 eV, whereas the barrier of *CO desorption decreased to 0.27 eV. As a result, the diatomic Fe-Ni site decreased the theoretical overpotential from 0.76 eV to 0.47 eV, significantly lowering the ECR barrier for CO production (Fig. 5c) [41]. Similar results were also reported by Zhao's work for a bridge-type homo-nuclear Fe DASC with Fe2-N6 sites [53]. The DFT simulations revealed that neighboring Fe-Fe configuration in the Fe2N6 site facilitate the CO2 activation via concurrently bonding the C and O atoms of CO2 molecule with a stretched C-O bond, as the ΔG of *CO2 formation decreased to −0.03 eV on the Fe2N6 site, considerably lower than that of +0.59 eV on the FeN4 site, consistent with the results of CO2 temperature programmed desorption measurements. The ΔG of *CO desorption from the bare Fe2N6 site was calculated to be 1.37 eV, which is higher than that of 1.03 eV on the FeN4 site. Nevertheless, the moiety of *CO bonded Fe2N6 took up a second CO2 molecule with a much milder ΔG of 0.90 eV, and the subsequent formed *CO + *CO configuration could easily desorb one CO molecule with a small ΔG of 0.20 eV. As a result, the largest energy barrier for CO production on the Fe2N6 site was lower than that on the FeN4 site, suggesting the advanced ECR performance on the DASC for CO production (Fig. 5d) [53].

3.3.2. ECR mechanism on heterogeneous DASCs constructed with Cu, In and SnIn contrast to the metals mentioned above, the Cu atoms in single-atom sites are usually regarded as neither performing any advantages for CO2 activation or *CO desorption, whereas the single-atom Cu catalysts can produce hydrocarbon compounds via ECR with more than two electron transfers. However, to date, CO is still the main product of experimental ECR on the DASC constructed with Cu atom participation, which may be attributed to the synergy and electron interaction of the dual metal atoms. For instance, Shen et al. investigated the CO production mechanism for a bridge-type Ni-Cu DASC [74]. DFT simulations and experimental results revealed that CO2 molecule tended to be adsorbed on the Ni atom for the diatomic Ni-Cu, and the adsorption and protonation of CO2 were enhanced on the diatomic Ni-Cu sites, as the electron orientation from the Cu site to Ni site reduced the antibonding orbital coupling between Ni and C atoms in CO2 (Fig. 5e). Moreover, the electron-deficient Cu atom in the diatomic site would serve as a spontaneous enrichment center for *H, which could offer an inexhaustible proton source to overcome the kinetic barriers of the ECR intermediates protonation. By these means, the Ni-Cu DASC achieved enhanced performance in CO production, surpassing the ECR performance on corresponding single-atom Cu or Ni catalysts (Fig. 5f). Similarly, Yi et al. also found that CO2 activation was more likely to occur on the Co sites for a marriage-type CoCu DASC, as the free energy barrier of CO2 activation on the Co sites was lower than that on the Cu sites. In addition, the calculated free energy diagrams for ECR revealed that the CoCu-DASC properly reduced the free energy barrier for *COOH formation and *CO desorption, as the CO2 activation and *CO desorption suffered larger free energy barriers on the single-atom Cu sites and single-atom Co sites, respectively. Further DOS calculations clearly demonstrated that the electronic interaction between the neighboring Co and Cu atoms tuned the d-band center of CoCu-DASC to a more moderate location, which resulted in a mild binding energy for the intermediates on the active sites [73]. When ECR is carried out on the DASCs constructed by Cu and Fe atoms anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon, the CO2 molecule tends to be adsorbed on the Fe atoms as well. With the electronic interaction of the neighboring Cu atoms, the charge density of the Fe atoms will be tuned, resulting in a lower d-band center than the Fe-N4 sites, which makes the Cu-Fe DASCs perform better CO2 activation properties than the corresponding SACs. In addition, considering the solvation effect and the transform state, the bridge-type Cu-Fe-N6-C site is supposed to reduce the energy barrier of the C-O bond breaking [85–87]. However, it is worth noting that the desorption of *CO from the Cu-Fe DASCs has not been significantly improved. Besides, in deference to the experimental results, the present studies of ECR on Cu-based DASCs do not explain why the CO2 has not been deeply reduced to other hydrocarbon compounds.

For the In or Sn participated DASCs, the synergistic effect and the electronic interaction of the two metal atoms in the diatomic site also lead to facilitating the CO2 activation. Take a marriage-type oxygen-bridged In-Ni DASC for instance, due to the synergistic effect of In-Ni dual-sites and O atom bridge, the O-In-N6-Ni site exhibits lower energy barrier for *COOH formation than the single-atom In and Ni sites, respectively, where the CO2 molecule tends to be adsorbed on the Ni atom in the DASC. Additionally, the diatomic site also retards the undesired hydrogen evolution reaction [78]. Similar conclusions have also been drawn for the Ni-Sn DASC and Cu-Sn DASC [77,79]. The C and one O atom of CO2 molecular simultaneously bond to the neighboring Cu and Sn atom on the Cu-Sn DASC, thus facilitate the CO2 activation progress (Fig. 5g). Moreover, the HCOOH production has been considered on the Cu-Sn DASC. The calculated energy barrier of HCOOH formation on the Cu-Sn site is significantly higher than that of *CO desorption, providing a reasonable explanation for the dominant CO production [79].

3.4. ECR competing with hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) on heterogeneous DASCsGiven that the HER is a dominant competitive reaction to ECR, the selectivity of ECR is crucial for DASCs. Since the energy barriers of ECR are significantly reduced for DASCs, the influence caused by the synergy of the neighboring metal atoms for HER is diluted, consistent with the high ECR efficiency. The difference between thermodynamic limiting potentials for ECR and HER (UL(CO2)-UL(H2), UL is the lowest potential that all reaction steps are downhill in free energy) is usually employed to investigate the relationship between ECR and HER on DASCs. In Ren's work, the NiFe-N-C DASC shows a more positive UL(CO2)-UL(H2) value than Fe-N-C, illustrating the higher ECR selectivity on the DASC [41]. CuN2SnN2/Gr exhibits a positive UL(CO2)-UL(H2) value, while the corresponding SACs show negative values, demonstrating the ECR is more favorable to HER on the DASCs (Fig. 5h).

4. Conclusions and perspectivesThis review summarized and underlined the progress of DASCs for ECR by spotlighting the challenges of precise DASCs fabrication and characterization, as well as the advanced ECR performance and reaction mechanism on DASCs. We highlighted the inter-metal interaction and the synergistic effect of the adjacent metal atoms in the DASCs for improving CO2 activation and *CO desorption, superior to that on the SACs. We believe that a good understanding of the advanced ECR performance on DASCs is beneficial for guiding the future efficient catalyst design for ECR, and the field of DASCs will provide exciting opportunities in ECR. However, to bridge the wide gap between the fundamental research and practical application, more efforts are still urgently needed to be devoted into DASC application from the perspective of ECR development. To boost the ECR performance on the DASCs, several perspective aspects are highlighted by the following key points:

(1) Precise fabrication and accurate characterization of DASC. It is the most fundamental issue for DASCs to fabricate uniform and well-defined diatomic sites. For the most present preparation methods of DASCs, it is difficult to be distinguished with the preparation of SACs. And it is inevitable to introduce single-atom sites into the DASCs. There is not a specific definition for the acceptable metal atom distance range of DASCs at present. The formation mechanism of diatomic-metal site is still remaining to be further elucidated. For the characterization of DASCs, since the metal loading in the DASCs is usually small, the single-atom sites may play a role that cannot be underestimated in electrocatalysis. On the other hand, it also brings more difficulties for the accurate characterization of the catalysts, although HAADF-STEM and XFAS are powerful tools for material characterization, the results obtained by them only reflect a local area or an average value of a certain region. Moreover, subject to the current unclear mechanism for the formation of diatomic sites, it is still a challenge to further improve the ECR performance by tuning the coordination of the two anchored metal atoms. Therefore, more attention should be drawn to the fabrication method and the formation mechanism of DASC.

(2) More in-depth reaction mechanism. At present, most of the theoretical studies are based on DFT calculations assuming a simple model with ideal conditions, where the transform state, solvents and mass transfer are usually neglected. This inevitably leaves a big gap between computer simulation and experimental measurements. Only few works provide further investigations on the distance effect of the two metal atoms in diatomic site and the threshold effect of inter-metal interaction for DASCs. Therefore, more parameters and complex material models are suggested to be considered for investigating the reaction mechanism in terms of computer simulation for ECR on DASCs. Meanwhile, it is well known that the electrocatalysts may reconstruct during the reaction, which affects the judgment of the real active site for ECR. Therefore, more efforts on in-situ characterizations should be carried out to monitor the real-time dynamic evolution of the diatomic site. In addition, there are still few studies comparing the properties and catalytic mechanisms of DASCs with different configurations in ECR, which call for more in-depth studies in the future.

(3) Reaction system enlargement and stability evaluation. At present, most electrochemical tests for ECR on DASCs are carried out in an H-cell reactor, which may be favorable for investigating the reaction mechanism for DASCs. However, as an ultimately application-oriented technology, it is not feasible to perform ECR reactions in an H-cell reactor, due to the low reaction current density in an H-cell reactor, which is far from the current density for industrial applications. In addition to the short reaction time, the characterization of catalyst after a long-term reaction is often missing in the stability evaluation of the DASC electrode. Therefore, more relevant studies are called to be carried out in a flow cell reactor or membrane electrode assembly reactor with a larger working area, as well as evaluating the stability of DASC under higher current density, which will provide greater significance for promoting the application of DASCs in ECR.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by "Pioneer" and "Leading Goose" R&D Program of Zhejiang (No. 2023C03017), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22225606, 22261142663, and 22176029), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2023M730491), Natural Science Foundation of Huzhou City (No. 2022YZ22).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109139.

| [1] |

K. Zhao, X. Quan, ACS Catal. 11 (2021) 2076-2097. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c04714 |

| [2] |

A. Liu, M. Gao, X. Ren, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 3541-3562. DOI:10.1039/C9TA11966C |

| [3] |

N.S. Spinner, J.A. Vega, W.E. Mustain, Catal. Sci. Technol. 2 (2012) 19-28. DOI:10.1039/C1CY00314C |

| [4] |

Y. Wang, J. Liu, Y. Wang, et al., Small 13 (2017) 1701809. DOI:10.1002/smll.201701809 |

| [5] |

H. Yoshio, W. Hidethi, T. Toshio, K. Osamu, Electrochim. Acta 39 (1994) 1833-1839. DOI:10.1016/0013-4686(94)85172-7 |

| [6] |

J. Tuo, Y. Zhu, L. Cheng, et al., ChemSusChem 12 (2019) 2644-2650. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201901058 |

| [7] |

Y. Wang, P. Han, X. Lv, et al., Joule 2 (2018) 2551-2582. DOI:10.1016/j.joule.2018.09.021 |

| [8] |

T.N. Nguyen, M. Salehi, Q.V. Le, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 10068-10095. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c02643 |

| [9] |

J. Gu, C.S. Hsu, L. Bai, et al., Science 364 (2019) 1091-1094. DOI:10.1126/science.aaw7515 |

| [10] |

F. Pan, H. Zhang, K. Liu, et al., ACS Catal. 8 (2018) 3116-3122. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.8b00398 |

| [11] |

X. Zheng, B. Li, Q. Wang, et al., Nano Res. 15 (2022) 7806-7839. DOI:10.1007/s12274-022-4429-9 |

| [12] |

C. Yan, H. Li, Y. Ye, et al., Energ. Environ. Sci. 11 (2018) 1204-1210. DOI:10.1039/C8EE00133B |

| [13] |

X. Wang, Z. Chen, X. Zhao, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57 (2018) 1944-1948. DOI:10.1002/anie.201712451 |

| [14] |

Y. Zhang, L. Jiao, W. Yang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 7607-7611. DOI:10.1002/anie.202016219 |

| [15] |

K. Li, S. Zhang, X. Zhang, et al., Nano Lett. 22 (2022) 1557-1565. DOI:10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c04382 |

| [16] |

X. Wang, Y. Wang, X. Sang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 4192-4198. DOI:10.1002/anie.202013427 |

| [17] |

W. Ni, Z. Liu, Y. Zhang, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2003238. DOI:10.1002/adma.202003238 |

| [18] |

D. Liu, Q. He, S. Ding, L. Song, Adv. Energy Mater. 10 (2020) 2001482. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202001482 |

| [19] |

X. Guo, J. Gu, S. Lin, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 5709-5721. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b13349 |

| [20] |

J. Jiao, R. Lin, S. Liu, et al., Nat. Chem. 11 (2019) 222-228. DOI:10.1038/s41557-018-0201-x |

| [21] |

Y. Wang, X. Cui, J. Zhang, et al., Prog. Mater. Sci. 128 (2022) 100964. DOI:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2022.100964 |

| [22] |

H. Wang, M.S. Bootharaju, J.H. Kim, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 2264-2270. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c10435 |

| [23] |

Y. Chen, J. Lin, B. Jia, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) e2201796. DOI:10.1002/adma.202201796 |

| [24] |

C. Dong, Y. Li, D. Cheng, et al., ACS Catal. 10 (2020) 11011-11045. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.0c02818 |

| [25] |

W. Zhang, Y. Chao, W. Zhang, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) e2102576. DOI:10.1002/adma.202102576 |

| [26] |

F. Li, X. Liu, Z. Chen, Small Methods 3 (2019) 1800480. DOI:10.1002/smtd.201800480 |

| [27] |

Y. Zang, Q. Wu, S. Wang, et al., Phys. Rev. Appl. 19 (2023) 024003. DOI:10.1103/PhysRevApplied.19.024003 |

| [28] |

L. Jiao, W. Ye, Y. Kang, et al., Nano Res. 15 (2021) 959-964. |

| [29] |

T. He, A.R.P. Santiago, Y. Kong, et al., Small 18 (2022) e2106091. DOI:10.1002/smll.202106091 |

| [30] |

D. Yao, C. Tang, X. Zhi, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) e2209386. DOI:10.1002/adma.202209386 |

| [31] |

J. Ding, F. Li, J. Zhang, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145 (2023) 11829-11836. DOI:10.1021/jacs.3c03426 |

| [32] |

Y. Chen, J. Lin, Q. Pan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202306469. DOI:10.1002/anie.202306469 |

| [33] |

A. Pedersen, J. Barrio, A. Li, et al., Adv. Energy Mater. 12 (2022) 2102715. DOI:10.1002/aenm.202102715 |

| [34] |

J. Zhang, Q. Huang, J. Wang, et al., Chinese J. Catal. 41 (2020) 783-798. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2067(20)63536-7 |

| [35] |

Z. Zhang, X. Xu, ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12 (2020) 56987-56994. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c16362 |

| [36] |

L. Pan, J. Wang, F. Lu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202216835. DOI:10.1002/anie.202216835 |

| [37] |

X. Zhou, K. Han, K. Li, et al., Adv. Mater. 34 (2022) e2201859. DOI:10.1002/adma.202201859 |

| [38] |

Y. Peng, B. Lu, S. Chen, Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1801995. DOI:10.1002/adma.201801995 |

| [39] |

Y. Hu, Z. Li, B. Li, C. Yu, Small 18 (2022) 2203589. DOI:10.1002/smll.202203589 |

| [40] |

H. Zhang, H. Wang, L. Zhou, et al., Appl. Catal. B 328 (2023) 122544. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122544 |

| [41] |

W. Ren, X. Tan, W. Yang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 6972-6976. DOI:10.1002/anie.201901575 |

| [42] |

T. Ding, X. Liu, Z. Tao, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143 (2021) 11317-11324. DOI:10.1021/jacs.1c05754 |

| [43] |

M. Fan, R.K. Miao, P. Ou, et al., Nat. Commun. 14 (2023) 3314. DOI:10.1038/s41467-023-38935-2 |

| [44] |

L. Jiao, H.L. Jiang, Chem 5 (2019) 786-804. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2018.12.011 |

| [45] |

H. Cheng, X. Wu, M. Feng, et al., ACS Catal. 11 (2021) 12673-12681. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.1c02319 |

| [46] |

W. Ye, S. Chen, Y. Lin, et al., Chem 5 (2019) 2865-2878. DOI:10.1016/j.chempr.2019.07.020 |

| [47] |

P. Jiao, D. Ye, C. Zhu, et al., Nanoscale 14 (2022) 14322-14340. DOI:10.1039/D2NR03687H |

| [48] |

B. Jiang, H. Sun, T. Yuan, et al., Energy Fuels 35 (2021) 8173-8180. DOI:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.1c00758 |

| [49] |

Z. Zeng, L.Y. Gan, H.B. Yang, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 4088. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-24052-5 |

| [50] |

Z. Lu, B. Wang, Y. Hu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 2622-2626. DOI:10.1002/anie.201810175 |

| [51] |

L. Zhang, R. Si, H. Liu, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 4936. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-12887-y |

| [52] |

H. Chen, Y. Zhang, Q. He, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 2364-2368. DOI:10.1039/C9TA13192B |

| [53] |

X. Zhao, K. Zhao, Y. Liu, et al., ACS Catal. 12 (2022) 11412-11420. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.2c03149 |

| [54] |

C. Du, Y. Gao, H. Chen, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 16994-17001. DOI:10.1039/D0TA06485H |

| [55] |

J.J. Rehr, R.C. Albers, Rev. Mod. Phys. 72 (2000) 621-654. DOI:10.1103/RevModPhys.72.621 |

| [56] |

J. Chan, M.E. Merrifield, A.V. Soldatov, M.J. Stillman, Inorg. Chem. 44 (2005) 4923-4933. DOI:10.1021/ic048871n |

| [57] |

H. Zhang, G. Liu, L. Shi, J. Ye, Adv. Energy Mater. 8 (2018) 1701343. DOI:10.1002/aenm.201701343 |

| [58] |

R. Qin, K. Liu, Q. Wu, N. Zheng, Chem. Rev. 120 (2020) 11810-11899. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00094 |

| [59] |

K. Leng, J. Zhang, Y. Wang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 32 (2022) 2205637. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202205637 |

| [60] |

Z. Zhao, M. Hu, T. Nie, et al., Environ. Sci. Technol. 57 (2023) 4556-4567. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.2c09336 |

| [61] |

L. Li, K. Yuan, Y. Chen, Acc. Mater. Res. 3 (2022) 584-596. DOI:10.1021/accountsmr.1c00264 |

| [62] |

S. Back, Y. Jung, ACS Energy Lett. 2 (2017) 969-975. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00152 |

| [63] |

X. Cui, W. An, X. Liu, et al., Nanoscale 10 (2018) 15262-15272. DOI:10.1039/C8NR04961K |

| [64] |

Y. Li, H. Su, S.H. Chan, Q. Sun, ACS Catal. 5 (2015) 6658-6664. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.5b01165 |

| [65] |

G. Luo, Y. Jing, Y. Li, J. Mater. Chem. A 8 (2020) 15809-15815. DOI:10.1039/D0TA00033G |

| [66] |

Q. Huang, H. Liu, W. An, et al., ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7 (2019) 19113-19121. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b05042 |

| [67] |

Y. Ouyang, L. Shi, X. Bai, et al., Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 1807-1813. DOI:10.1039/C9SC05236D |

| [68] |

J. Su, R. Ge, Y. Dong, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 6 (2018) 14025-14042. DOI:10.1039/C8TA04064H |

| [69] |

X.M. Liang, H.J. Wang, C. Zhang, et al., Appl. Catal. B 322 (2023) 122073. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.122073 |

| [70] |

H. Yang, Y. Wu, G. Li, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 12717-12723. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b04907 |

| [71] |

S. Chen, B. Wang, J. Zhu, et al., Nano Lett. 21 (2021) 7325-7331. DOI:10.1021/acs.nanolett.1c02502 |

| [72] |

K. Zhao, X. Nie, H. Wang, et al., Nat. Commun. 11 (2020) 2455. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-16381-8 |

| [73] |

J.D. Yi, X. Gao, H. Zhou, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202212329. DOI:10.1002/anie.202212329 |

| [74] |

Y. Shen, H. Zhang, B. Chen, et al., Appl. Catal. B 330 (2023) 122654. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122654 |

| [75] |

X. Zu, X. Li, W. Liu, et al., Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) 1808135. DOI:10.1002/adma.201808135 |

| [76] |

H. Shang, T. Wang, J. Pei, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59 (2020) 22465-22469. DOI:10.1002/anie.202010903 |

| [77] |

W. Xie, H. Li, G. Cui, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 7382-7388. DOI:10.1002/anie.202014655 |

| [78] |

Z. Fan, R. Luo, Y. Zhang, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62 (2023) e202216326. DOI:10.1002/anie.202216326 |

| [79] |

W. Liu, H. Li, P. Ou, et al., Nano Res. 16 (2023) 8729-8736. DOI:10.1007/s12274-023-5513-5 |

| [80] |

X. Cao, L. Zhao, B. Wulan, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202113918. DOI:10.1002/anie.202113918 |

| [81] |

M.J. Sun, Z.W. Gong, J.D. Yi, et al., Chem. Commun. 56 (2020) 8798-8801. DOI:10.1039/D0CC03410J |

| [82] |

Y. Li, C. Chen, R. Cao, et al., Appl. Catal. B 268 (2020) 118747. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2020.118747 |

| [83] |

L. Jiao, X. Li, W. Wei, et al., Appl. Catal. B 330 (2023) 122638. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2023.122638 |

| [84] |

Y. Li, B. Wei, M. Zhu, et al., Adv. Mater. 33 (2021) 2102212. DOI:10.1002/adma.202102212 |

| [85] |

F. Wang, H. Xie, T. Liu, et al., Appl. Energ. 269 (2020) 115029. DOI:10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115029 |

| [86] |

R. Yun, F. Zhan, X. Wang, et al., Small 17 (2021) e2006951. DOI:10.1002/smll.202006951 |

| [87] |

M. Feng, X. Wu, H. Cheng, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 9 (2021) 23817-23827. DOI:10.1039/D1TA02833B |

| [88] |

H. Han, J. Im, M. Lee, D. Choo, Appl. Catal. B 320 (2023) 121953. DOI:10.1016/j.apcatb.2022.121953 |

| [89] |

B. Deng, M. Huang, K. Li, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202114080. DOI:10.1002/anie.202114080 |

| [90] |

B. Deng, X. Zhao, Y. Li, et al., Sci. China Chem. 66 (2022) 78-95. |

| [91] |

X. Wei, Y. Liu, X. Zhu, et al., Adv. Mater. 35 (2023) e2300020. DOI:10.1002/adma.202300020 |

| [92] |

X. Qin, S. Zhu, F. Xiao, et al., ACS Energy Lett. 4 (2019) 1778-1783. DOI:10.1021/acsenergylett.9b01015 |

| [93] |

B. Deng, M. Huang, X. Zhao, et al., ACS Catal. 12 (2021) 331-362. |

| [94] |

Z. Chen, K. Mou, S. Yao, L. Liu, ChemSusChem 11 (2018) 2944-2952. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201800925 |

| [95] |

L.D. Chen, M. Urushihara, K. Chan, J.K. Nørskov, ACS Catal. 6 (2016) 7133-7139. DOI:10.1021/acscatal.6b02299 |

| [96] |

J. Hao, H. Zhu, Y. Li, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 404 (2021) 126523. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2020.126523 |

| [97] |

T. Gan, D. Wang, Nano Res. 17 (2024) 18-38. DOI:10.1007/s12274-023-5700-4 |

| [98] |

H. Zhang, J. Li, S. Xi, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 14871-14876. DOI:10.1002/anie.201906079 |

| [99] |

C. Shi, H.A. Hansen, A.C. Lausche, J.K. Norskov, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16 (2014) 4720-4727. DOI:10.1039/c3cp54822h |

| [100] |

H. Gu, J. Wu, L. Zhang, Nano Res. 15 (2022) 9747-9763. DOI:10.1007/s12274-022-4270-1 |

| [101] |

Q. Sun, C. Jia, Y. Zhao, C. Zhao, Chin. J. Catal. 43 (2022) 1547-1597. DOI:10.1016/S1872-2067(21)64000-7 |

| [102] |

J. Zhang, W. Cai, F.X. Hu, et al., Chem. Sci. 12 (2021) 6800-6819. DOI:10.1039/D1SC01375K |

| [103] |

W. Dong, N. Zhang, S. Li, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 10 (2022) 10892-10901. DOI:10.1039/D2TA01285E |

| [104] |

H.B. Yang, S.F. Hung, S. Liu, et al., Nat. Energy 3 (2018) 140-147. DOI:10.1038/s41560-017-0078-8 |

| [105] |

W. Ju, A. Bagger, G.P. Hao, et al., Nat. Commun. 8 (2017) 944. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-01035-z |

| [106] |

J. Jin, J. Wicks, Q. Min, et al., Nature 617 (2023) 724-729. DOI:10.1038/s41586-023-05918-8 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35