For an extended period, energetic materials that could rapidly release vast quantities of energy when suitably initiated have been extensively used in space exploration, military affairs and civil applications [1-7]. Energetic ionic salts have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional energetic materials, with each offering high heat of formation, as well as reduced toxicity and environmental impact, however, their practical implementation is hindered by limited thermal stability, corrosivity toward specific metals, and sensitivity to impact and friction. To overcome these challenges, it is essential to develop novel synthetic strategies in order to enhance their performance [8-10]. Reticular chemistry and subject-object chemistry prove to be promising approach for the design and synthesis of energetic ionic-based materials with high performance [11-13]. Encapsulation of high-energy ions into the pores or skeletons of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), covalent organic frameworks (COFs), or hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs) has been extensively explored tune their energetic properties [14-17]. These studies dramatically prompted the development of high-performance energetic materials and further encouraged us to explore desensitization of energetic ionic salts. However, the comprehensive and systematic regulation of susceptibility, corrosivity, and thermal stability for high oxygen content and strong corrosive ions, such as perchlorate anion and dinitramide anion, is currently lacking in research when employing this strategy. Thus, further studies to fully understand and optimize the performance of energetic materials containing such ions are necessary.

Triaminoguanidine salts belong to the category of the nitrogen-rich energetic ionic salts [18-20]. In this work, we developed a series of guanidine-based energetic two-dimensional (2D) COFs (denoted as COF-TAGX-Dha, X = Cl, ClO4, N(NO2)2) through the reaction of triaminoguanidinium chloride (TAGCl), triaminoguanidinium perchlorate (TAGClO4), triaminoguanidinium dinitramide (TAGN(NO2)2) with 2,5-dihydroxyterephthaladehyde (Dha) based on Schiff base condensation reaction. As expected, these COFs possess many highlights, such as higher stabilities, lower sensitivity and better corrosion resistance as compared with their corresponding triaminoguanidine precursors. It is worth noting that the onset decomposition temperature of the resulting COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha is 262 ℃, which is the highest value among those of reported N(NO2)2-based compounds. Moreover, incorporating triaminoguanidine salts into COF-TAGX-Dha greatly reduces their impact and friction sensitivities, which could be attributed to their layer-by-layer stacking structure. More importantly, due to the adsorption behavior between imine moiety of COFs and surface of metals, the resulting materials showed excellent corrosion resistance. This work provides a reference value for enhancing the safety of energetic ionic salts.

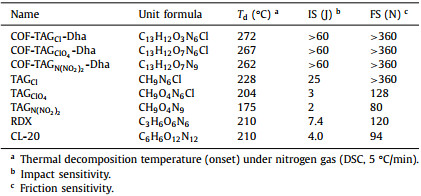

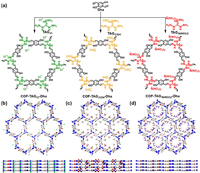

Typically, imine-linked COF-TAGX-Dha were carried out by suspending Dha (0.15 mmol) with TAGX (0.1 mmol) in the mixed solvent of mesitylene and tetrahydrofuran in the presence of water, which was then heated at 80 ℃ for 3 days (Fig. 1a). Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analyses of COF-TAGCl-Dha, COF-TAGClO4-Dha and COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha exhibited a peak at 5.26°, 5.44°, 5.44°, respectively, which can be assigned to the (100) facet of the regularly ordered lattice. The relatively weak peaks reflected low crystallinity of these ionic COFs. This might be ascribed to the presence of repulsive interactions between the positively charged guanidinium groups, which hampered the formation of a highly ordered and stacked structure [21-23]. Additionally, the major broad peak at approximately 27° can be attributed to the (001) reflection plane, which indicates the π-π interactions between the interlayer of 2D COF [24]. The structural models for COF-TAGX-Dha were constructed by building two possible 2D hexagonal layers including eclipsed (AA) and staggered (AB) stacking with Materials Studio software. As revealed in Figs. 2a-c, the simulated PXRD patterns from the AA-stacking model are well matched with the experimentally observed curves, and exhibited small agreement factors (Rp = 3.77% and Rwp = 4.70% for COF-TAGClO4-Dha, Rp = 2.99% and Rwp = 3.77% for COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha), thus suggesting the validity of the proposed model (Figs. 1b-d). The unit cell parameters were determined after Pawley refinement as a = 21.2672Å, b = 21.3126Å, c = 10.2279Å, α = β = 90°, and γ = 120° for COF-TAGClO4-Dha; a = 21.2672 Å, b = 21.3126 Å, c = 10.2279Å, α = β = 90°, and γ = 120° for COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha. In the Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra, observation of the band at 1620 cm−1 due to the C=N bonds confirms the formation of imine linkages in COF-TAGX-Dha, which are accompanied by the disappearance of the C=O peak at approximately 1666 cm−1 and the -NH2 stretching band at 3300 cm−1 in the precursors. Meanwhile, the presence of typical anions inside the framework was confirmed by their respective stretching bands. The bands at 1522 and 1015 cm−1 were derived from NO2 and N3 groups from N(NO2)2− anions in COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha, while the stretching band at 1087 cm−1 was attributed to the ClO4− anions in COF-TAGClO4-Dha (Figs. 2d-f) [25]. Solid-state 13C CP-MAS NMR spectroscopy further verified the characteristic resonance signals for the C=N groups at approximately 150 ppm (Fig. S4 in Supporting information) [26-28].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. (a) Schematic representation of the imine-linked triaminoguanidine COFs with tunable anions (Cl, ClO4 and N(NO2)2). (b-d) Top and side views of (b) COF-TAGCl-Dha, (c) COF-TAGClO4-Dha, and (d) COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha constructed in AA stacking model. (C, gray; H, white; N, blue; O, red; Cl, green). | |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. PXRD patterns of (a) COF-TAGCl-Dha, (b) COF-TAGClO4-Dha, and (c) COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha. FT-IR spectra of (d) COF-TAGCl-Dha, (e) COF-TAGClO4-Dha, (f) COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha and corresponding monomers. | |

The scanning electron microscopy and transmission electron microscopy images showed that COF-TAGX-Dha crystallize with a stacked-layer structure (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). The permanent porosity of COF-TAGX-Dha was assessed by N2 adsorption isotherms recorded at 77 K, and they exhibited type-II adsorption isotherms [29]. Using the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) model, the surface areas of COF-TAGCl-Dha, COF-TAGClO4-Dha and COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha were calculated to be 28.9, 30.3 and 26.0 m2/g, respectively (Figs. S6-S8 in Supporting information). The relatively low BET surface area of the COF-TAGX-Dha likely resulted from the low crystallinity of prepared COF-TAGX-Dha and pore blocking by the counter anions [23, 30, 31]. Based on the nonlocal density functional theory model, the pore size distributions of COF-TAGCl-Dha, COF-TAGClO4-Dha and COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha are centered at 1.4, 1.5 and 1.6 nm, respectively.

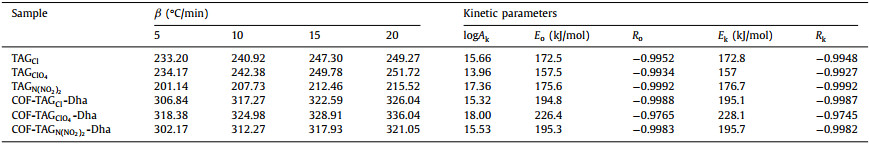

The thermal stabilities of these samples were examined using differential scanning (DSC) measurements at a heating rate of 5 ℃/min (Table 1 and Fig. S10 in Supporting information). All of these materials exhibit sharp exothermic peaks, indicating the collapse of the structure. The onset decomposition temperature (Td) of COF-TAGX-Dha is above 260 ℃, which is superior to those of TAGX (TAGCl, 228 ℃; TAGClO4, 204 ℃; TAGN(NO2)2, 175 ℃) and conventional energetic materials 1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazinane (RDX, Td = 210 ℃) and 2,4,6,8,10,12-hexanitrohexaazaisowurtzitane (CL-20, Td = 210 ℃) [32]. In particular, the thermal decomposition temperature of COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha (262 ℃) is the highest among those of the previously reported dinitramide-based energetic materials.

|

|

Table 1 Physicochemical properties of materials compared with some traditional energetic materials. |

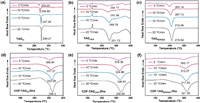

Due to their high thermostability, the Kissinger and Ozawa methods were employed to investigate the thermodynamic properties of the decomposition process (Fig. 3). The Kissinger (Eq. 1) and Ozawa-Doyle (Eq. 2) equations are as follows:

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. DSC curves of triaminoguanidine salts (a) TAGCl, (b) TAGClO4, (c) TAGN(NO2)2 and corresponding COFs (d) COF-TAGCl-Dha, (e) COF-TAGClO4-Dha, (f) COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha at different heating rates. | |

In the equations, Tp stands for the peak temperature, R equals to 8.314 J mol−1 K−1, β is the linear heating rate set at 5, 10, 15 and 20 ℃/min. C represents a constant. A (s−1) and Ea (kJ/mol) refers to the pre-exponential factor and activation energy, respectively. By averaging the results from the Kissinger method and Ozawa method, the values of activation energy for the COF-TAGX-Dha (X = Cl, ClO4, N(NO2)2) are 194.95, 227.25 and 195.5 kJ/mol, whereas the raw guanidinium salts are 172.65, 157.25 and 176.15 kJ/mol (Table 2). The higher Ea values indicate better thermal stability [33]. In addition, these values fall in the range of 80–250 kJ/mol, indicating that synthesized COFs can be used as energetic materials from a kinetic perspective [34]. In combination with the experimental and calculated results, we concluded that the encapsulation of energetic anions within catatonic COFs could improve thermal stability of these guests. In addition, the energy density of COF-TAGX-Dha is range from 1.64 g/cm3 to 1.77 g/cm3, which is comparable to traditional energetic materials 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene (TNT, 1.65 g/cm3), RDX (1.80 g/cm3) and pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN, 1.76 g/cm3) (Table S1 in Supporting information) [35].

|

|

Table 2 Exothermic peak temperature and kinetic parameters of COF-TAGX-Dha and corresponding parent salts. |

Impact and friction sensitivities (IS and FS, respectively) are the key indicators for evaluating the safety of energetic materials. Low sensitivities of explosives can reduce the risk of serious and fatal accidents throughout the manufacturing and application process. In this work, the sensitivity values of samples were determined by using the standard BAM techniques (Table 1). All of these energetic salts were sensitive to friction and impact simulations (TAGCl: IS = 25 J, FS > 360 N; TAGClO4: IS = 3 J, FS = 128 N; TAGN(NO2)2: IS = 2 J, FS = 80 N). In contrast, COF-TAGX-Dha exhibited lower sensitivity (IS > 40 J, FS > 360 N). It is notable that these values are also higher than that of typical explosives RDX (7.4 J, 120 N) and CL-20 (4.0 J, 94 N). These remarkable increases in the mechanical stability may arise from the π-π stacking interactions between the vertically stacked 2D layers, which can rapidly transform the mechanical energy from external stimuli into interlayer motion to reduce their sensitivity [36-39]. The above results indicate that trapping the energetic salts into 2D COFs is a feasible strategy to decrease their sensitivities.

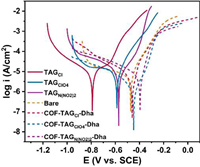

The corrosion capacity of COFs and TAGX to mild steel is studied by electrochemical and surface analysis techniques in order to illustrate how the corrosion of these materials to metal utensils is reduced by assembling the triaminoguanidine salts into Schiff base COFs. Typical potentiodynamic polarization curves of bare and sample-coated mild steel (MS) electrodes in 3.5% NaCl solution at 298 K are depicted in Fig. 4. Compared with the bare MS, the corrosion potential (Ecorr) of TAGX-coated MS decreased from −0.473 V to −0.7917 V (TAGCl). The COFs-coated MS exhibited positive shifted over bare MS, with the highest Ecorr being −0.3965 V for COF-TAGN(NO2)2-Dha. Meanwhile, the corrosion current density decreased following the order of TAGX-coated > bare > COFs-coated MS, which clearly shows that the COFs provide preferable protection for MS (Table S2 in Supporting information). This behavior can be attributed to the fact that abundant imine groups in the COFs act as the π-acceptor forming strong coordinate bonds with the metallic surface, which then increase the anticorrosion capacity [40-42].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 4. Potentiodynamic polarization curves of COFs and TAGX. | |

To observe the corrosion process of mild steel and copper sheets at high relative humidity (RH = 80%) directly, the morphologies of these metals were captured by optical microscopy following exposure to COFs and their precursors for 12, 36, 60 h, respectively. The results are shown in Figs. S10 and S11 (Supporting information). It can be seen clearly that TAGCl, TAGClO4 and TAGN(NO2)2 caused serious corrosion. Insoluble corrosion products are observed on the metallic surface. The FT-IR analysis indicated that these samples deteriorated obviously when they came in contact with mild steel and copper (Fig. S12 in Supporting information). On the contrary, these metals were not corroded when they came in contact with the COF-TAGX-Dha. Simultaneously, the structures of COFs remained intact as characterized by PXRD and FT-IR analyses (Fig. S13 in Supporting information). These experimental results are consistent with the electrochemical characterizations. Taken together, COFs displayed good corrosion resistance for metals, while energetic salts possessed poor corrosion resistance. Therefore, immobilizing energetic anions in 2D imine-based COFs is a promising strategy to effectively enhance the corrosion resistance of energetic materials for metals.

In summary, this work performed a systematic study on the TAG salt based energetic COFs. Our results confirmed that the π-π stacking interactions among the layers of 2D COFs efficiently reduced the mechanical sensitivity compared to their raw salts and traditional explosives (CL-20, RDX). Besides, the strategy of encapsulating energetic salts into imine-linked COFs significantly improve corrosion resistance to metal benefiting from the coordinate bond between imine moieties and metal surface. This work highlights that COFs provide an intriguing platform to construct high performance energetic materials.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 22175155, 21825106 and 22275168), the Henan Science Fund for Excellent Young Scholars (No. 212300410084), the opening project of State Key Laboratory of Explosion Science and Technology (Beijing Institute of Technology) (No. KFJJ22–05 M).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108537.

| [1] |

Q.H. Zhang, J.M. Shreeve, Chem. Rev. 114 (2014) 10527-10574. DOI:10.1021/cr500364t |

| [2] |

T.O. Yan, C. Yang, J.C. Ma, et al., Chem. Eng. J. 428 (2022) 131400. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2021.131400 |

| [3] |

J.L. Zhang, J. Zhou, F.Q. Bi, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 2375-2394. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.01.026 |

| [4] |

C. Wang, H.M. Guo, R. Pang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 32 (2022) 2207524. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202207524 |

| [5] |

C. Wang, Y.J. Wang, C.L. He, et al., JACS Au 1 (2021) 2202-2207. DOI:10.1021/jacsau.1c00334 |

| [6] |

J. Song, Y.S. Shi, Y. Lu, et al., Nano Res. 15 (2022) 1698-1705. DOI:10.1007/s12274-021-3888-8 |

| [7] |

Q. Ma, Z.Q. Zhang, W. Yang, et al., Energ. Mater. Front. 2 (2021) 69-85. DOI:10.1016/j.enmf.2021.01.006 |

| [8] |

A.O. Diallo, C. Len, A.B. Morgan, et al., Sep. Purif. Technol. 97 (2012) 228-234. DOI:10.1016/j.seppur.2012.02.016 |

| [9] |

R.P. Singh, R.D. Verma, D.T. Meshri, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45 (2006) 3584-3601. DOI:10.1002/anie.200504236 |

| [10] |

H.X. Gao, J.M. Shreeve, Chem. Rev. 111 (2011) 7377-7436. DOI:10.1021/cr200039c |

| [11] |

P.H. Zhang, Z.F. Wang, P. Cheng, et al., Coord. Chem. Rev. 438 (2021) 213873. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2021.213873 |

| [12] |

L. Zhang, L.Z. Yi, Z.J. Sun, et al., Aggregate 2 (2021) e24. DOI:10.1002/agt2.24 |

| [13] |

E. Troschke, M. Oschatz, I.K. Ilic, Exploration 1 (2021) 20210128. DOI:10.1002/EXP.20210128 |

| [14] |

J.C. Zhang, Y. Du, K. Dong, et al., Chem. Mater. 28 (2016) 1472-1480. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b04891 |

| [15] |

Q. Lai, L. Pei, T. Fei, et al., Nat. Commun. 13 (2022) 6937. DOI:10.1038/s41467-022-34686-8 |

| [16] |

J.C. Zhang, Y.A. Feng, R.J. Staples, et al., Nat. Commun. 12 (2021) 2146. DOI:10.1038/s41467-021-22475-8 |

| [17] |

Y.S. Shi, J. Song, F.C. Cui, et al., Nano Res. 16 (2023) 1507-1512. DOI:10.1007/s12274-022-4697-4 |

| [18] |

J.W. Wu, J.G. Zhang, T.L. Zhang, et al., Cent. Eur. J. Energ. Mater. 12 (2015) 417-437. |

| [19] |

M. Gratzke, S. Cudziło, Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 46 (2021) 1509-1525. DOI:10.1002/prep.202100092 |

| [20] |

V.V. Serushkin, V.P. Sinditskii, V.Y. Egorshev, et al., Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 38 (2013) 345-350. DOI:10.1002/prep.201200155 |

| [21] |

H.W. Chen, H.Y. Tu, C.J. Hu, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 896-899. DOI:10.1021/jacs.7b12292 |

| [22] |

H.J. Wang, J.S. Zhao, Y. Li, et al., Nano-Micro Lett. 14 (2022) 216. DOI:10.1007/s40820-022-00968-5 |

| [23] |

S. Mitra, S. Kandambeth, B.P. Biswal, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 2823-2828. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b13533 |

| [24] |

L.P. Guo, J. Zhang, Q. Huang, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2856-2866. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.02.065 |

| [25] |

J. Zhou, L. Ding, F.Q. Zhao, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 31 (2020) 554-558. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2019.05.008 |

| [26] |

H.J. Da, C.X. Yang, X.P. Yan, Environ. Sci. Technol. 53 (2019) 5212-5220. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b06244 |

| [27] |

Z.Y. Guo, H.F. Jiang, H. Wu, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60 (2021) 27078-27085. DOI:10.1002/anie.202112271 |

| [28] |

Z.Y. Guo, H. Wu, Y. Chen, et al., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134 (2022) e202210466. DOI:10.1002/ange.202210466 |

| [29] |

J.L. Li, J.H. Wang, F. Shui, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 34 (2023) 107917. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2022.107917 |

| [30] |

S.Y. Yao, Y. Yang, Z.W. Liang, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 33 (2023) 2212466. DOI:10.1002/adfm.202212466 |

| [31] |

L.J. Chen, M.C. Huang, B. Chen, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 33 (2022) 2867-2882. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2021.10.060 |

| [32] |

J.H. Zhang, J.M. Shreeve, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136 (2014) 4437-4445. DOI:10.1021/ja501176q |

| [33] |

S.M. Pourmortazavi, M. Rahimi-Nasrabadi, I. Kohsari, et al., J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 110 (2012) 857-863. DOI:10.1007/s10973-011-1845-6 |

| [34] |

R.Z. Hu, Z.Y. Yang, Y.J. Liang, Thermochim. Acta 123 (1988) 135-151. DOI:10.1016/0040-6031(88)80017-0 |

| [35] |

E. Sebastiao, C. Cook, A.G. Hu, et al., J. Mater. Chem. A 2 (2014) 8153-8173. DOI:10.1039/C4TA00204K |

| [36] |

C.Y. Zhang, X.C. Wang, H. Huang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130 (2008) 8359-8365. DOI:10.1021/ja800712e |

| [37] |

B.B. Tian, Y. Xiong, L.Z. Chen, et al., CrystEngComm 20 (2018) 837-848. DOI:10.1039/C7CE01914A |

| [38] |

F.B. Jiao, Y. Xiong, H.Z. Li, et al., CrystEngComm 20 (2018) 1757-1768. DOI:10.1039/C7CE01993A |

| [39] |

L. Qian, H.W. Yang, H.L. Xiong, et al., Energ. Mater. Front. 1 (2020) 74-82. DOI:10.1016/j.enmf.2020.09.004 |

| [40] |

C. Verma, M.A. Quraishi, Coord. Chem. Rev. 446 (2021) 214105. DOI:10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214105 |

| [41] |

K.R. Ansari, D.S. Chauhan, M.A. Quraishi, et al., Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 144 (2020) 305-315. DOI:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.12.106 |

| [42] |

M.M. Abdelsalam, M.A. Bedair, A.M. Hassan, et al., Arabian J. Chem. 15 (2022) 103491. DOI:10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103491 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35