b CAS Key Laboratory of Soft Matter Chemistry, Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China

High-performance elastomers are considered as a class of significant strategic materials with unique high elasticity, and they play important roles in many emerging fields, including tires, coatings, and flexible electronic devices [1–4]. Introducing of crosslinked networks can usually enhance the properties of elastomers, such as toughness, load-carrying capacity and solvent resistance, which is highly desirable for many demanding applications [5,6]. For permanent crosslinked network, the mobility of the polymer chains is limited, resulting in losing the ability of reprocessability [7–9]. This is typically overcome by incorporating covalent adaptable networks into polymer matrix. Compared to the permanent crosslinked networks, covalent adaptable networks defined as vitrimers have received plenty of interest in recent years, which presented many advantages in reprocessing and durability of polymers [10–19], including disulfide exchange [20,21], Diels-Alder reaction [22,23], transesterification [24,25], and boronic ester bond exchange [26–28].

Given the unique feature of fast stress relaxation, transamination of vinylogous urethanes has rapidly become one of the most promising reversible reactions for vitrimers synthesis introduced by Winne and Du Prez et al. [29–31]. The concept of vitrimeric polymer networks is well understood that the dynamic exchange between the formed vinylogous urethane and the presence of pendent amines [32,33]. And this strategy has been successfully applied in the polymerization areas enabling the synthesis of different polymers, including vitrimeric thermoplastics [34] thermosets [35,36]and elastomers [37,38]. Despite these recent advances, the design of monomer with special structure is limited, and the additional property studies of the vitrimeric polymers except reprocessing property have gained much less attention in this system. Therefore, the objective of this work is to establish a strategy to prepare vitrimeric polymer materials with unique topological structures and enhanced properties.

In this contribution, we demonstrated the synthesis of vitrimeric elastomers utilizing polycondensation. The topological structures of polymers were tuned by varying the feeding ratios of monomers, including bisacetoacetate, hex–substituted bisacetoacetate, bisamine and tris(2-aminoethyl)amine. Biacetoacetate monomer with long chain branch was investigated to regulate the chemical and network structures of the polymers for the first time inspired by the research of polyolefin elastomers (POE) [39–42]. With these structural manipulations, thermal, mechanical and elastic properties of the vitrimeric elastomers were well adjusted. And other additional material properties were also demonstrated, such as reprocessing, water vapor/oxygen barrier, adhesive properties and degradability. The ease of high-performance vitrimeric elastomers using polycondensation in this work demonstrates exciting opportunities for recyclable polymers and will attract wide application interests.

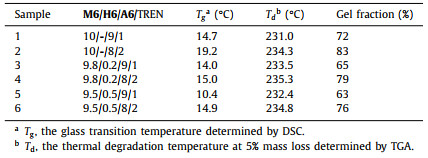

Bisacetoacetate (M6) was synthesized from 1, 6-hexanediol, following a high yielding acetoacetylation reaction with tert–butyl acetoacetate (Scheme 1). The hex–substituted bisacetoacetate (H6) was synthesized using the nucleophilic substitution reaction of M6 and 1-iodopentane under basic conditions. Using p-toluenesulfonic acid as catalyst (PTSA, 5 mol%), the polycondensation process was performed in neat at 120℃ for 3 h with mechanical stirring, and in vacuum for 3 h to remove water combining of M6, H6, 1, 6-hexamethylenediamine A6 and tris(2-aminoethyl)amine (TREN, crosslinker). The vitrimeric polymer networks (Samples 1–6) were accessed through regulating the feeding mole ratios of four different contents, and the samples designation are summarized in Table 1. M6, A6 and TREN with mole ratios of 10/9/1 was employed to generate the polymer Sample 1. The contents of crosslinker were varied to regulate the network structure of the vitrimeric elastomer with the ratios of 10/8/2 (Sample 2). To investigate the influence of different bisacetoacetate monomer to polymer material properties, H6 was incorporated into the polymer matrix with four contents in different feeding ratios (Samples 3–6). Gel fraction analysis of these crosslinked networks showed a moderate gel fraction content (63%~83%), indicating the crosslinking structures for all samples. Increased gel fraction of the vitrimer was observed with the increased amount of crosslinker TREN.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Synthesis of the vitrimeric elastomers via polycondensation of monomers bisacetoacetate (M6, H6), 1, 6-hexamethylenediamine (A6) and tris(2-aminoethyl)amine (TREN). Reaction conditions: Catalyst PTSA (5 mol%), 120℃ for 6 h. | |

|

|

Table 1 Samples designations and feeding monomer molar ratios of the synthesized vitrimeric elastomers. |

The progress of the reaction was qualitatively confirmed by the conversion of the acetoacetate group into vinylogous urethane as shown in FT-IR spectra (Fig. S1 in Supporting information). The complete disappearance of ketone vibration bands at 1710 and 1740 cm−1 and the appearance of new vibration bands at 1600 and 1650 cm−1, assigned to C=C and C=O of vinylogous urethane indicated the high efficiency of this polymerization reaction. The polymer was also characterized by high-temperature 1H NMR spectra at 120℃ in C2D2Cl4, and the characteristic peaks of 8.5, 4.5, 4.1, 3.2 and 1.9 ppm are attributed to the generated vinylogous urethane (Fig. S1). Different from the other reports, long chain-substituted acetoacetate monomer H6 was used in this work. To further investigate the reactive activity of these two biacetoacetate monomers (M6 and H6) during the polycondensation, model reactions were conducted using Me- or hex-substituted monoacetoacetate with hexylamine in neat at 120℃ catalyzed by PTSA. Within 30 min, the Me- and Hex-substituted monoacetoacetates can be converted to the targeted vinylogous urethane products respectively indicated by the 1H NMR spectra (Figs. S2-S4 in Supporting information) and the time-dependent kinetic study (Fig. S5 in Supporting information). The presented characterizations of the polymers and model reactions demonstrated the high efficiency of the polycondensation process.

The thermal properties of polymers are known to be dependent on their chemical structures. Therefore, the thermal properties of the samples were studied systematically with DSC and TGA correlated with their structures. Fig. S6a (Supporting information) shows the glass transition temperature (Tg) of the obtained polymers determined by DSC (Samples 1–6). For the polymer Samples 1 and 2, increased Tg was observed (14.7 ℃ vs. 19.2 ℃) with enhanced crosslinking density, indicating that the chain mobility was more restricted for Sample 2. Similar trends were presented for the polymers (Samples 3 vs. 4, 14.0 ℃ vs. 15.0 ℃; Samples 5 vs. 6, 10.4 ℃ vs. 14.9 ℃). The Tg decreased with the increase of the H6 content which was ascribed to the enhanced polymer chain mobility through the introduction of flexible aliphatic chain. From the TGA curves, all prepared polymers in this work exhibited a comparable Td at about 230 ℃ which displayed good thermostability (Fig. S6b in Supporting information).

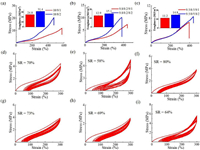

Tensile strength analysis was performed for the prepared polymer samples. The polymer films were pressed at 120 ℃ under a pressure of 5 MPa for 6 min and cooled to 25 ℃. These films were subsequently cut into dog-bone-shaped tensile bars with 12 mm gage length, 2 mm width and thickness of 0.5 mm. Incorporation of one tenth of crosslinker, the polymer sample exhibited the tensile strength up to 11.8 MPa and elongation at break 570% (Sample 1, Fig. 1a) with a toughness of 24.8 MJ/m3. Continuing to increase the amount of TREN, the polymer showed enhanced mechanical properties up to 20 MPa and elongation at break 470% (Sample 2, Fig. 1a) with maximum toughness of 31.4 MJ/m3. Introducing H6, decreased tensile strength was observed, which may be ascribed to low chain entanglement arising from the incorporated flexible long chain in polymer matrix (Samples 3 and 4, Fig. 1b) with toughness of 12.9 and 15.1 MJ/m3 respectively [43]. Similar trend was observed for polymers (Samples 5 and 6, Fig. 1c, tensile strength 6~9 MPa; elongation at break 400%) when increasing the feeding ratio of H6.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Mechanical properties of elastomers Samples 1–6. (a-c) Tensile stress-strain curves and toughness of elastomers at 25℃. (d-i) Cyclic stress-strain curves of ten cycles at a strain of 300% for samples measured at 25 ℃. | |

To investigate the elastic recovery property, the cyclic stress-strain measurements of polymer samples were carried out with each sample extended to 300% strain over 10 cycles. Strain recovery value (SR) is an important parameter to evaluate the elasticity and the high values represents a high elasticity. As is shown, the Sample 1 exhibited good elastic property with strain recovery value of 70% at 25 ℃ (Fig. 1d). Increasing the content of crosslinker TREN, the strain recovery value decreased to 58% (Sample 2, Fig. 1e) compared to Sample 1. This was attributed to the increased crosslinking density of the elastomers with increasing content of TREN, which restricted the mobility of the polymer chains. By introducing H6, the elastomers showed excellent elasticity with higher strain recovery value 80% (Sample 3, Fig. 1f) and 73% (Sample 4, Fig. 1g) respectively. Continuing to increase the feeding ratio of H6, a slight decrease of elasticity was observed with the strain recovery values 69% (Sample 5, Fig. 1h) and 64% (Sample 6, Fig. 1i) respectively. When TREN was fixed at 20 mol%, introducing a certain amount of flexible long chain into polymer matrix could decrease the chain entanglement and consequently enhance the mobility of polymer chain which enabled the increased elasticity (58% vs. 73% vs. 64%; Figs. 1e, g and i). This strategy was also successfully applied in the designing of the polyolefin elastomers [39–42].

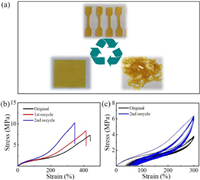

The reprocessing property of these elastomer materials can be ascribed to the thermally induced associative exchange mechanism in the network. For reprocessability study, the elastomers were repeatedly cut into chips and then compression molded for 6 min at 120 ℃ under 5 MPa for several times (Fig. 2a). The reprocessed elastomers were subjected to tensile testing, which shows the stress-strain curves of the reprocessed elastomer. Obviously, the recycled samples exhibited a slight increase of tensile strengths (10.2 vs. 8.3 vs. 7.3 MPa) and decrease of elongation at break (340% vs. 410% vs. 430%) compared to the original elastomers (Fig. 2b). And the cyclic stress-strain curves showed the decreased elasticity after two reprocessed recycles (Fig. 2c, strain recovery values, 73% vs. 80%). This phenomenon might be attributed to the oxidation crosslinking reaction during hot press at 120℃ due to the existence of unsaturated vinylogous urethane.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (a) Reprocessing of Sample 3 at 120 ℃ for 6 min under pressure of 5 MPa. (b) Representative tensile stress-strain curves of the original Sample 3 and two cycles reprocessed at 25 ℃. (c) Cyclic stress-strain curves of the original Sample 3 and the second recycle at 25 ℃. | |

Considering the coordination of heteroatoms in polymer network, the vitrimeric elastomer may have specific interaction with metals, treated as a possible adhesive agent. Therefore, the adhesive performances of the elastomers sandwiched between two pieces of the tested substrates were evaluated by the lap shear tests. Stainless steel sheets were chosen to investigate the metal bonding capability of the elastomers. The elastomer can glue two stainless steel sheets and shows good bonding effect on the steel sheet surface (adhesive force, 108 N; displacement, 9.8 mm, Fig. 3a). Furthermore, the water vapor transmission rate and oxygen permeabilities of these polymers were also evaluated. The elastomers possessed a moderate permeability barrier character to water vapor with the water vapor transmission rate value of 16.3 g mm m-2 day−1 (Sample 1, Fig. 3b). Similar water vapor transmission rate value was observed for the elastomer (Sample 3, 20.8 g mm m-2 day−1). Specially, the elastomers exhibited an outstanding barrier character to oxygen with a low value of 0.17 and 0.19 Barrer, respectively. These results may arise from the alkyl chain and H-bonding induced chain packing of polymer enabling the network structure more compact [44,45]. The good barrier properties to atmospheric penetrants, such as water vapor and oxygen were required for packaging materials.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (a) Metal adhesive capability of the Sample 1. (b) Water vapor transmission rate and oxygen permeability of Samples 1 and 3. (c) Degradation of elastomer Sample 1 to monomers enabling the closed-loop recycling system. | |

Along with the huge annual production and intrinsic properties such as robustness and durability, the end-of-life treatment of post-consumer plastic wastes has become a serious problem [46]. Therefore, the development of recyclable and degradable polymers has received much attention, especially from synthetic chemistry perspective [47–53]. Considering the formed vinylogous urethane could mediate hydrolysis reaction under acid conditions efficiently, degradability of the vitrimeric elastomer networks was evaluated in this contribution. For instance, hydrolysis of elastomer Sample 1 in HCl/THF enabled its depolymerization to form monomer M6 in quantitative yield after neutralization and extraction, as depicted in Fig. S7 (Supporting information). And the recovered monomer can be used to access the vitrimer elastomer again in the recycling system (Fig. 3c). The excellent degradability in this work provided a second pathway to prepare recyclable polymers, establishing the dual closed loops to achieve chemical circularity including reprocessability research.

In summary, a series of highly elastic and recyclable vitrimeric elastomers were synthesized via polycondensation using M6, H6, A6 and TREN. The chemical and topological structures were tuned by varying the feeding ratios of different contents. With these structural manipulations, the performances including thermal and mechanical properties were fine-tuned as well. Benefiting from the introduction of long chain branch, the vitrimeric elastomers exhibited great elastic recovery property (SR up to 80%). Excellent reprocessing property was observed for the prepared samples because of the thermally induced associative exchange mechanism in the network. And the elastomers also exhibited excellent water vapor/oxygen barrier and adhesive properties. Specially, the elastomers presented great degradability to monomers under acid conditions which enabled the elastomer synthesis again in closed-loop recycling system. The synthesis of high-performance vitrimeric elastomers using polycondensation in this work demonstrates exciting opportunities for recyclable polymers and will attract wide application interests.

Declaration of competing interestsThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Nos. 21971230, U19B6001, 22201003). We thanked Excellent Research and Innovation Team Project of Anhui Province (No. 2022AH010001), Anhui Province Key Laboratory of Environment-friendly Polymer Materials. And we are grateful for the mentorship and strongly support from Professor Changle Chen (USTC).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108874.

| [1] |

Y. Nurhamiyah, A. Amir, M. Finnegan, et al., ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13 (2021) 6720-6730. DOI:10.1021/acsami.0c23155 |

| [2] |

Y.C. Li, J.C. Li, W.H. Li, H.P. Du, Smart. Mater. Struct. 23 (2014) 123001. DOI:10.1088/0964-1726/23/12/123001 |

| [3] |

M. Park, J. Park, U. Jeong, Nano Today 9 (2014) 244-260. DOI:10.1016/j.nantod.2014.04.009 |

| [4] |

L.Z. Zhang, Z.H. Liu, X.L. Wu, et al., Adv. Mater. 31 (2019) 1901402. DOI:10.1002/adma.201901402 |

| [5] |

R.C. Du, Z.C. Xu, C. Zhu, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 30 (2020) 1907139. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201907139 |

| [6] |

S.L. Chen, F.F. Wang, Y.J. Peng, et al., Macromol. Rapid. Commun. 36 (2015) 1687-1692. DOI:10.1002/marc.201500257 |

| [7] |

S.Q. Ma, D.C. Webster, F. Jabeen, Macromolecules 49 (2016) 3780-3788. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00594 |

| [8] |

P. Taynton, K. Yu, R.K. Shoemaker, et al., Adv. Mater. 26 (2014) 3938-3942. DOI:10.1002/adma.201400317 |

| [9] |

T. Liu, C. Hao, L.W. Wang, et al., Macromolecules 50 (2017) 8588-8597. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.7b01889 |

| [10] |

C.J. Kloxin, C.N. Bowman, Chem. Soc. Rev. 42 (2013) 7161-7173. DOI:10.1039/C3CS60046G |

| [11] |

W.K. Zou, J.T. Dong, Y.W. Luo, Q. Zhao, T. Xie, Adv. Mater. 29 (2017) 1606100. DOI:10.1002/adma.201606100 |

| [12] |

Z.P. Zhang, M.Z. Rong, M.Q. Zhang, Prog. Polym. Sci. 80 (2018) 39-93. DOI:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.03.002 |

| [13] |

G.M. Scheutz, J.J. Lessard, M.B. Sims, B.S. Sumerlin, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141 (2019) 16181-16196. DOI:10.1021/jacs.9b07922 |

| [14] |

P. Chakma, D. Konkolewicz, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58 (2019) 9682-9695. DOI:10.1002/anie.201813525 |

| [15] |

M. Guerre, C. Taplan, J.M. Winne, F.E.D. Prez, Chem. Sci. 11 (2020) 4855-4870. DOI:10.1039/D0SC01069C |

| [16] |

P.R. Christensen, A.M. Scheuermann, K.E. Loeffler, B.A. Helms, Nat. Chem. 11 (2019) 442-448. DOI:10.1038/s41557-019-0249-2 |

| [17] |

X.Y. Lu, P. Xie, X.X. Xiang, J.Q. Sun, Macromolecules 55 (2022) 2557-2565. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.2c00272 |

| [18] |

Y. Deng, D.H. Qu, B.L. Feringa, Angew. Chem. 134 (2022) e202209. |

| [19] |

J.Y. Zhang, L.H. Zeng, J. Feng, Chin. Chem. Lett. 28 (2017) 168-183. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2016.07.015 |

| [20] |

Y. Lai, X. Kuang, P. Zhu, et al., Adv. Mater. 30 (2018) 1802556. DOI:10.1002/adma.201802556 |

| [21] |

W.Q. Yuan, G.L. Liu, C.L. Huang, Y.D. Li, J.B. Zeng, Macromolecules 53 (2020) 9847-9858. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.0c01665 |

| [22] |

E. Trovatti, T.M. Lacerda, A.J.F. Carvalho, A. Gandini, Adv. Mater. 27 (2015) 2242-2245. DOI:10.1002/adma.201405801 |

| [23] |

X.X. Chen, M.A. Dam, K.J. Ono, et al., Science 295 (2002) 1698-1702. DOI:10.1126/science.1065879 |

| [24] |

C.F. He, S.W. Shi, X.F. Wu, T.P. Russell, D. Wang, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 6793-6796. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b03771 |

| [25] |

Y. Yang, Z.Q. Pei, Z. Li, Y. Wei, Y. Ji, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138 (2016) 2118-2121. DOI:10.1021/jacs.5b12531 |

| [26] |

Y. Chen, Z.H. Tang, X.H. Zhang, et al., ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 10 (2018) 24224-24231. DOI:10.1021/acsami.8b09863 |

| [27] |

X.T. Zhang, S.J. Wang, Z.K. Jiang, Y. Li, X.L. Jing, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142 (2020) 21852-21860. DOI:10.1021/jacs.0c10244 |

| [28] |

L. Odenwald, F.P. Wimmer, N.K. Mast, et al., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144 (2022) 13226-13233. DOI:10.1021/jacs.2c03778 |

| [29] |

W. Denissen, G. Rivero, R. Nicolaÿ, et al., Adv. Funct. Mater. 25 (2015) 2451-2457. DOI:10.1002/adfm.201404553 |

| [30] |

C. Taplan, M. Guerre, J.M. Winne, F.E.D. Prez, Mater. Horiz. 7 (2020) 104-110. DOI:10.1039/C9MH01062A |

| [31] |

W. Denissen, I.D. Baere, W.V. Paepegem, et al., Macromolecules 51 (2018) 2054-2064. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.7b02407 |

| [32] |

T. Stukenbroeker, W. Wang, J.M. Winne, et al., Polym. Chem. 8 (2017) 6590-6593. DOI:10.1039/C7PY01488K |

| [33] |

F.V. Lijsebetten, K.D. Bruycker, Y. Spiesschaert, J.M. Winne, F.E.D. Prez, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61 (2022) e202113872. DOI:10.1002/anie.202113872 |

| [34] |

S.Q. Zheng, Y. Liu, G.F. Si, M. Chen, Chin. J. Chem. 41 (2023) 2002. DOI:10.1002/cjoc.202300061 |

| [35] |

J.J. Lessard, G.M. Scheutz, R.W. Hughes, B.S. Sumerlin, ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2 (2020) 3044-3048. DOI:10.1021/acsapm.0c00523 |

| [36] |

P. Haida, G. Signorato, V. Abetz, Polym. Chem. 13 (2022) 946-958. DOI:10.1039/D1PY01237A |

| [37] |

M. Guerre, C. Taplan, R. Nicolay, J.M. Winne, F.E.D. Prez, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140 (2018) 13272-13284. DOI:10.1021/jacs.8b07094 |

| [38] |

W. Niu, Z. Zhang, Q.Y. Chen, P.F. Cao, R.C. Advincula, ACS Mater. Lett. 3 (2021) 1095-1103. DOI:10.1021/acsmaterialslett.1c00132 |

| [39] |

S.Y. Dai, S.K. Li, G.Y. Xu, C.L. Chen, Macromolecules 53 (2020) 2539-2546. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.0c00083 |

| [40] |

Y.K. Xiao, P.W. Liu, W.J. Wang, B.G. Li, Macromolecules 54 (2021) 10381-10387. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.1c01249 |

| [41] |

K.L. Zhang, P.W. Liu, W.J. Wang, et al., Macromolecules 51 (2018) 8790-8799. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.8b01711 |

| [42] |

X.Y. Song, L.X. Cao, R. Tanaka, T. Shiono, Z.G. Cai, ACS Macro. Lett. 8 (2019) 299-303. DOI:10.1021/acsmacrolett.9b00005 |

| [43] |

Z. Li, C.L. Ye, L.Y. Feng, Polymer 181 (2019) 121758. DOI:10.1016/j.polymer.2019.121758 |

| [44] |

A. Sangroniz, J.B. Zhu, X.Y. Tang, et al., Nat. Commun. 10 (2019) 3559. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-11525-x |

| [45] |

A. Sangroniz, A. Chaos, M. Iriarte, et al., Macromolecules 51 (2018) 3923-3931. DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.8b00833 |

| [46] |

R. Geyer, J.R. Jambeck, K.L. Law, Sci. Adv. 3 (2017) e1700782. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.1700782 |

| [47] |

L. Zhou, Z. Zhang, C.X. Shi, E.Y.X. Chen, Science 380 (2023) 64-69. DOI:10.1126/science.adg4520 |

| [48] |

Y. Zhang, B.T. Wang, Z.H. Guo, J. Chen, Z.P. Fang, Chin. Chem. Lett. 20 (2009) 1348-1352. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2009.05.013 |

| [49] |

G.F. Si, C.L. Chen, Nat. Synth. 1 (2022) 956-966. DOI:10.1038/s44160-022-00163-9 |

| [50] |

M. Häußler, M. Eck, D. Rothauer, S. Mecking, Nature 590 (2021) 423-427. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-03149-9 |

| [51] |

H. Du, L.L. Gao, W.P. Zhu, Z.Q. Shen, Chin. Chem. Lett. 23 (2012) 879-882. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2012.05.022 |

| [52] |

P. Shieh, W.X. Zhang, J.A. Johnson, Nature 583 (2020) 542-547. DOI:10.1038/s41586-020-2495-2 |

| [53] |

J.D. Feist, D.C. Lee, Y. Xia, Nat. Chem. 14 (2022) 53-58. DOI:10.1038/s41557-021-00810-2 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35