b Center for Tuberculosis Research, Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Disease, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, 21231-1044, United States;

c Shanghai Institute for Advanced Immunochemical Studies and School of Life Science and Technology, ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai 201210, China;

d Shanghai Key Laboratory of Green Chemistry and Chemical Process, School of Chemistry and Molecular Engineering, East China Normal University, Shanghai 200062, China

Tuberculosis (TB) is a chronic infectious disease caused by mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), which seriously endangers human health. The corona virus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has reversed years of global progress in tackling TB. TB deaths have increased for the first time in over a decade, according to the World Health Organization's (WHO) 2022 Global TB report [1]. In 2021, TB was the 13th leading cause of death globally, falling to the second place as a single cause but still accounting for about 1.6 million deaths, including 187,000 human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive cases, demonstrating that TB remains the most prevalent and deadly epidemic globally. Currently, the standard treatment for TB generally requires at least a six to nine months regimen of four first-line drugs to ensure complete eradication of TB. However, multidrug resistance (MDR) and extensive drug resistance (XDR) TB patients required a combination of more than seven antibiotics for more than 18 months, and the success rate of treatment was very limited [2,3]. An all-oral combination therapy consisting of recently approved antitubercular drugs (bedaquiline, pretomanid, and linezolid) was proposed at the Meeting on Combating Drug Resistance-Innovative TB Chemotherapy Plans organized by the TB Alliance. The research results showed that after six months of treatment, patients with drug-resistant TB had a success rate of 90% [4]. However, bedaquiline resistance has already emerged in a high TB burden country [5]. Developing antitubercular drugs with novel scaffolds and distinct mechanisms of action is of substantial significance for the clinical treatment of drug-resistant TB.

Mycobacterial membrane protein large (MmpL) is a group of membrane proteins encoded by the Mycobacterium genome, which belongs to the resistance, nodulation, and cell division proteins (RND) family, and has 13 subtypes [6]. All of them are involved in the relevant biological functions of mycobacterial cell membranes (play an essential role in the transport of lipids, polymers, and immunomodulators), and were found to rely on proton-motive force (PMF) as the energy for substrate transport [7,8]. Among the 13 MmpL subtypes, MmpL3 is an essential transmembrane protein for bacterial cell replication and survival [9-11]. The mmpL3 CRISPRi knockdown strain of Mtb had increased susceptibility to SQ109, a drug candidate against drug-resistant Mtb currently in Phase Ⅱb/Ⅲ clinical trials [12-15]. The sputum clearance rate of SQ109 for MDR-TB patients was similar to bedaquiline and delamanid. These studies further demonstrate the potential of MmpL3 as an antitubercular therapeutic target.

Several MmpL3 small-molecule inhibitors with different scaffolds have been reported (Fig. 1), including ethylenediamine (SQ109, 1), indole-2-carboxamides (ICA38, 2), adamantyl ureas (AU1235, 3), pyrroles (BM635, 4), and pyrazoles (rimonabant, 5 and 6) [16-19]. Notably, compound 4 has potent in vitro antitubercular activities and is currently in preclinical evaluation [20-22]. Rimonabant is the first type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1) antagonist for weight loss. Interestingly, it has also been found to show inhibitory activity on MmpL3 [19]. SQ109 is considered an MmpL3 inhibitor; however, no resistant mutants of SQ109 have been directly isolated in vitro or in vivo. In addition, SQ109 was found to interfere with menaquinone biosynthesis and electron transport [23].

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 1. Structures of representative MmpL3 inhibitors. | |

According to the four complexes structures of mycobacterium smegmatis (Msmg) MmpL3 and its inhibitors (SQ109, ICA38, AU1235, and rimonabant), the binding pocket consists of 5 binding regions (S1–S5) [16], including 4 hydrophobic regions S1 (V245, I319, V638), S2 (L686, V689, L708), S3 (V638, G641, L642), S5 (F260, S293, F649), and one hydrogen bonding region S4 (D645). All four inhibitors form an essential hydrogen bond with D645 blocking two pairs of Asp–Tyr-hydrogen bonds (Y256–D646; Y257–D645), thereby interfering with the proton transport function of MmpL3 (Fig. 2A). The five-membered aromatic heterocyclic module is a common structural unit in drugs, including the anti-tuberculosis field [24], as it can form dipole-dipole and π-stacking interactions and hydrogen bonds, possibly improving the solubility and binding capacity of biological targets. N-Containing five-membered heterocyclic derivatives with better physicochemical properties were reported to have significant antibacterial (including antitubercular) activities, including pyrrole [25-28], pyrazole [19,29], and 1,2,4-triazole [30-33] skeletons. The triazole heterocycles have been considered one of the most valuable scaffolds in drug discovery and development [34,35], and the 1,2,4-triazole structural unit processes relatively high calculated LogS value (−0.1254) compared to other heterocycles, e.g. pyrrole (LogS: −0.834) and pyrazole (LogS: −0.7903) (Fig. 2B). Herein, we present our design and development of a 1,2,4-triazole core containing MmpL3 inhibitors utilizing a structural-based approach. Compounds targeted to MmpL3 protein are generally lipophilic because of the hydrophobic nature of the binding site as aforementioned. However, too high cLogP may be deleterious as this will negatively impact aqueous solubility and plasma protein binding. Thus, we strive to balance lipid solubility and antitubercular activity during compound optimization. Structure–activity relationships (SARs) of N-heterocyclic (S5 region) and R1 (S1 region) and R2 (S2 region) were systematically explored.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 2. (A) The binding pocket of MmpL3 with 4 representative inhibitors SQ109 (orange sticks, PDB: 6AJG), ICA38 (yellow sticks, PDB: 6AJJ), AU1235 (light blue sticks, PDB: 6AJH), and rimonabant (pink sticks, PDB: 6AJI). (B) Design of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives. | |

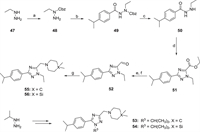

Two synthetic routes were exploited to access desired 1,2,4-triazole derivatives 14–46 and 53–56 (Schemes 1 and 2). Compounds 14–46 were synthesized from commercially available 4-fluoroaniline 7 and cuminaldehyde 9 via five steps (Scheme 1). The key 1,2,4-triazole intermediate 11 was synthesized according to a previously reported paper [36]. 4-Fluoroaniline 7 was first converted to diazonium salt by the treatment with NaNO2/HCl at 0 ℃. Then the diazonium salt was reacted with methyl 2-chloroacetoacetate to give hydrazonoyl chloride 8. Aldehyde 9 was converted to the oxime intermediate and underwent a 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition reaction with hydrazonoyl chloride 8 in the presence of Et3N to obtain the key 1,2,4-triazole intermediate 11. The 1,2,4-triazole 11 was further reduced and oxidized to the corresponding aldehyde 12 using sodium borohydride and Dess-Martin periodinane, respectively. Reductive amination of aldehyde 12 with various amines in the presence of sodium triacetoxyborohydride successfully obtained target compounds 14–41. Hydrolysis of methyl ester 11 under basic conditions afforded carboxylic acid 13, which was subjected to a subsequent amide condensation reaction with various amines to afford target compounds 42–46.

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 1. Synthesis of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives 14–46. Reagents and conditions: (a) (ⅰ) NaNO2, 3 mol/L HCl (aq.), 0 ℃, 1 h; (ⅱ) methyl 2-chloroacetoacetate, AcONa, EtOH, r.t., 4 h; (b) NH2OH·HCl, PhMe, r.t., 0.5 h; (c) Et3N, reflux, 1–2 h; (d) NaBH4, MeOH, r.t., overnight; (e) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h; (f) LiOH, MeOH:THF:H2O = 2:1:1, 50 ℃, 3 h; (g) various amines, NaBH(AcO)3, CH2Cl2, r.t., overnight; (h) various amines, EDCI, HOBt, DIPEA, CH2Cl2, r.t., 6 h. | |

|

Download:

|

| Scheme 2. Synthesis of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives 53–56. Reagents and conditions: (a) Cbz-Cl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 ℃, 3–4 h; (b) 4-propan-2-ylbenzoyl chloride, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 ℃–rt, 3–4 h; (c) 10% Pd/C, MeOH, H2, r.t., overnight; (d) ethyl thiooxamate, PhMe:AcOH = 10:1, 90 ℃, 10 h; (e) NaBH4, MeOH, r.t., overnight; (f) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, r.t., 2 h; (g) dimethyl piperidine or 4,4-dimethyl-1,4-azasilinane, NaBH(AcO)3, CH2Cl2, r.t., overnight. | |

The intermediate 48 was obtained via introducing a Cbz group and then interacted with 4-isopropylaniline to get intermediate 49 through the amide condensation reaction (Scheme 2). The Cbz protecting group of 49 was removed under the conditions of Pd/C and hydrogen to obtain the intermediate 50, followed by a cycloaddition reaction with ethyl thiooxamate to get the 1,2,4-triazole 51. The aldehyde 52 was synthesized via successively reduction and oxidation reactions using sodium borohydride and Dess-Martin periodinane, respectively. Finally, in the presence of sodium triacetoxyborohydride, intermediate 52 underwent reductive amination with 4,4-dimethylpiperidine or 4,4-dimethyl-1,4-azasilinane to obtain target compounds 55 or 56. Similarly, compounds 53 and 54 were obtained from starting material isopropyl hydrazine.

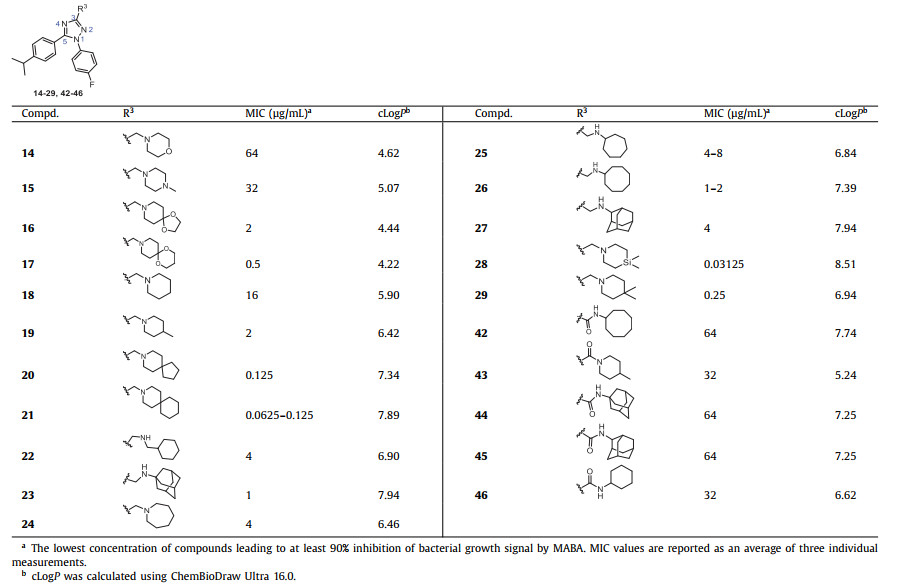

All final compounds were initially evaluated for their minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values against the Mtb strain H37Rv in a standard microplate Alamar blue assay (MABA) [37,38]. The initial round of SAR modifications was focused on the substitutions on the 3-position of 1,2,4-triazole core (R3 group), which presumably occupy the essential S1 hydrophobic pocket and forms an essential hydrogen bond with residue D645 of the MmpL3 protein. Poce et al. reported that the 4-fluorophenyl and 4-isopropylphenyl substituents attached to the pyrrole or pyrazole core could effectively occupy the S1 and S2 hydrophobic regions of MmpL3 [21,28]. Therefore, we first introduced these two substituents to the 1- and 5-positions (R1 and R2 groups) of the 1,2,4-triazole core. Various sterically hindered N-containing cyclics (N-morpholine, N-1-methylpiperazine, N-1,4-dioxa-8-azaspiro[4.5]decane, N-1,5-dioxa-9-azaspiro[5.5]undecane, N-piperidine, N-4-methylpiperidine, N-8-azaspiro[4.5]decane, N-3-azaspiro[5.5]undecan, N-cyclohexylmethanamine, N-1/2-amantadine, N-azepane, N-cycloheptylamine, and N-cyclooctylamine) were selected for R3. As shown in Table 1, cyclic amines 19–27 generally showed moderate to good antitubercular activities with MIC values ranging from 0.0625 µg/mL to 4 µg/mL, except compound 18 (MIC = 16 µg/mL). Inserting N or O atoms into cyclic amines (14–17) resulting a decrease in activity (MIC = 0.5–64 µg/mL), suggesting that lipophilicity of the R3 group is crucial. The increase in the steric effect of cyclic amine (18–20) is accompanied by an obvious improvement in activity. It is speculated that larger hydrophobic groups can insert deeply into the S5 hydrophobic pocket (F260, S293, F649). The spiroanalogues 20 and 21 were the most potent active compounds with MIC values of 0.0625–0.125 µg/mL. The bioisosteric replacement of a carbon atom with a silicon atom holds the potential to improve the properties of a compound and to create intellectual property space [39]. Ramesh et al. reported that the activity of N-4,4-dimethylazasilyl analogues was improved due to the enhancement of lipophilicity [19]. In our case, compound 28 (MIC = 0.03125 µg/mL) bearing an N-4,4-dimethylazasilyl moiety showed 8-fold more active than the corresponding N-4,4-dimethylpiperidine 29 (MIC = 0.25 µg/mL). Replacing amines with amides (42–46) resulted in inactivity due to the loss of the essential hydrogen bond with the carboxyl of D645.

|

|

Table 1 The antitubercular activity of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives 14–29 and 42–46 against Mtb strain H37Rv. |

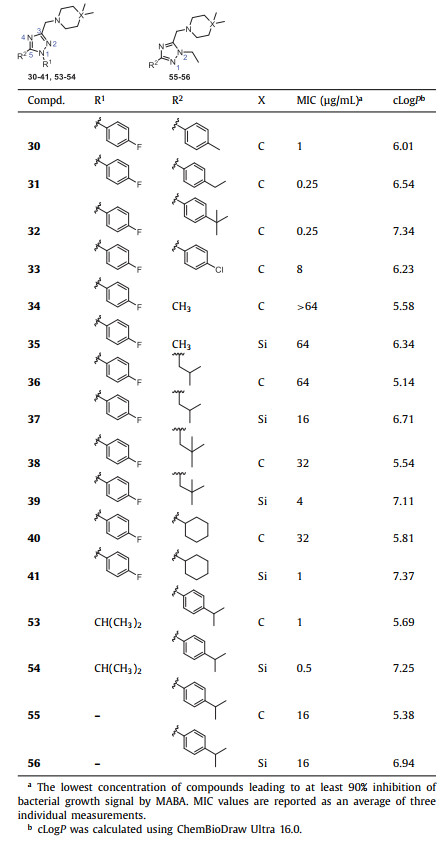

Subsequent SAR investigation was focused on the 1- and 5-positions of 1,2,4-triazole core (R1 and R2 groups, Table 2). We introduced substituents at the para position of the phenyl group at the R2 position to explore the electronic effects. The introduction of electron-donating groups (EWGs) such as methyl (30), ethyl (31), and tert‑butyl (32) showed similar antitubercular activities (MIC = 0.25–1 µg/mL) to the 4-isopropyl 29 (MIC = 0.25 µg/mL). In the contrast, introducing an electron-withdrawing group (EWG; -Cl, compound 33), resulted in a 32-fold reduction in activity, thus terminating further exploration of EWG. Replacing the substituted phenyl ring with aliphatic groups at the 1-position (-iPrCH2) or 5-position (-Me, -iPrCH2, -tBuCH2, cyclohexyl) of 1,2,4-triazole core decreased the antitubercular activity (compounds 34–41, MIC = 1–64 µg/mL) compared to compounds 28 (MIC = 0.03125 µg/mL) and 29 (MIC = 0.25 µg/mL). These results suggest that higher lipophilic moieties at the R1 or R2 are more favorable in activity. Consistent with the trend in compounds 18–20, the increase in the steric hindrance of the 1-position (-iPrCH2, 4-isopropylphenyl) and 5-position (-Me, -iPrCH2, -tBuCH2, cyclohexyl, 4-fluorophenyl) substituents was accompanied by an increase in antitubercular activity. Moving the alkyl substituent to the 2-N led to a significant loss of activity (55 and 56, MIC = 16 µg/mL).

|

|

Table 2 The antitubercular activity of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives 30–41 and 53–56 against Mtb strain H37Rv. |

We plotted the correlation between the antitubercular activity of triazole derivatives and cLogP values. As shown in Fig. S1 (Supporting information), the antitubercular activity of triazole compounds is positively correlated with the cLogP values. Compounds 21 and 28 exhibited the most potent antitubercular activity, accompanied by the highest cLogP values. Compounds with higher lipophilicity showed more potent activity.

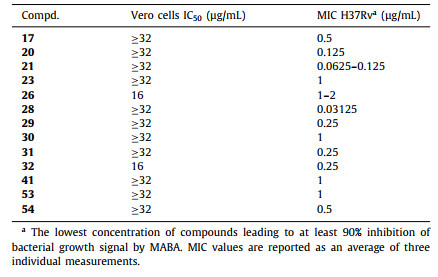

The active compounds with MIC values less than 1 µg/mL were selected to further evaluate their cytotoxicity profiles against Vero cells derived from African green monkey kidneys. A comparison of the Vero cell toxicity [half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values] and the MIC values for Mtb growth inhibition gives a measure of the general toxicity profile of the compound of interest [40]. As shown in Table 3, all tested compounds showed low cytotoxicity in Vero cells with IC50 values greater than 16 µg/mL. Notably, compounds 21 and 28 with the most potent antitubercular activity, showed neglectable cytotoxicity (IC50 ≥ 32 µg/mL).

|

|

Table 3 Vero toxicity of compounds 17, 20, 21, 23, 26, 28–32, 41, 53, and 54. |

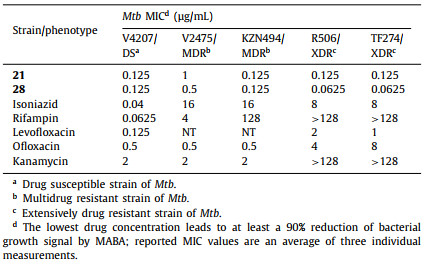

Compounds 21 and 28 obtained were antitubercular activity evaluated on susceptible-TB (V4207), MDR-TB (V2475 and KZN494), and XDR-TB (R506 and TF274) strains of clinical isolates [41]. First-line antitubercular drugs (isoniazid and rifampin) and second-line antitubercular drugs (levofloxacin, ofloxacin, and kanamycin) were used as a positive control (Table 4). To our delight, compounds 21 and 28 had equally potent activity against susceptible Mtb strains and all MDR and XDR clinical isolates tested. The high activities against the MDR and XDR-TB highlight the potential use of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives to treat drug-resistant Mtb and the likelihood that they will not exhibit cross-resistance with currently used medications.

|

|

Table 4 The antitubercular activity of compounds 21 and 28 against susceptible, MDR, and XDR strains of Mtb. |

The physicochemical properties of pyrazole/triazole-based derivatives 21, 28, and bedaquiline were predicted using ADMET Lab (Table S1 in Supporting information). The molecular weights and hydrogen-bond acceptor numbers of the three compounds are in accordance with Lipinski's rule of five (RO5). Compounds 21, 28 and bedaquiline have similar antitubercular activity in vitro, but the LogS of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives 21 and 28 are lower than bedaquiline (LogS: −6.16, −5.97 vs. −8.79). Among them, compound 21 showed the lowest cLogP value of 7.90 similar to bedaquiline (cLogP: 7.25). The permeability coefficient (suggestion: >−5.15 cm/s) of Caco-2 monolayers (Papp) is commonly used to evaluate human intestinal permeability [42]. Compounds 21 and 28 have log10Papp values of −4.79 and −4.69, respectively, indicating that they have the potential to traverse the cell membranes. The predicted plasma protein binding (PPB) degrees of compounds 21 and 28 were 86.8% and 90.5%, suggesting that these compounds may have a long plasma half-life.

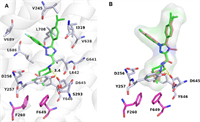

To investigate the binding mode of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives and MmpL3, we performed molecular docking studies with representative compound 28. The crystal structure used was MmpL3-rimonabnt (PDB: 6AJI) [16], the docking calculation was carried out using the Schrödinger's Glide-XP module, and Pymol 2.5 was used for later protein and small molecule processing. Compound 28 successfully binds to the active pocket of MmpL3 (docking score = −13.19) located in the center of the MmpL3. As shown in Fig. 3A, the N atom of N-4,4-dimethylazasilyl and the carboxyl of residues D645 formed a key hydrogen bond (3.4 Å), which blocked the original hydrogen bond pairs (Y256–D646; Y257–D645) and affected the proton-motive force of MmpL3 protein. In addition, compound 28 also forms hydrophobic interactions with hydrophobic pockets of MmpL3, including N-4,4-dimethylazasilyl and residues F260, S293, F649; 4-fluorophenyl and residues V245, I319, V638; 4-isopropylphenyl and residues L686, V689, L708. A stacking docking study (Fig. 3B) showed that the binding modes of 28 and rimonabant were similar. However, the hydrophobic dimethyl moiety of 28 could insert more deeply into the hydrophobic region S5 (F260, F649) than the piperidinyl of rimonabant, leading to a more potent antitubercular activity.

|

Download:

|

| Fig. 3. (A) Proposed binding mode of compound 28 (green) with MmpL3 (PDB: 6AJI). (B) Superposed docking poses of 28 and rimonabant (orange). | |

Further, to verify the potential biding target of 1,2,4-triazoles compounds, we conducted a binding affinity study of representative compound 28 with Msmg MmpL3 using a microscale thermophoresis (MST) assay. As shown in Fig. S2 (Supporting information), 28 directly binds to Msmg MmpL3 with a Kd value of 25.2 µmol/L, which is slightly more potent than that of rimonabant (Kd = 29.5 µmol/L) [16].

Structure-based rational design and medicinal chemistry optimization focused on maximizing MmpL3 target occupancy led to the discovery of 1,2,4-triazole derivatives, a potent antitubercular agent effective against drug-susceptible/resistant mycobacteria. Representative compounds 21 and 28 showed the most potency against Mtb strain H37Rv with MIC values of 0.0312–0.125 µg/mL. The cytotoxic evaluations of compounds 21 and 28 to Vero cells showed the lowest toxicity (IC50 ≥ 32 µg/mL). More importantly, compounds 21 and 28 had equally potent activities against the clinical isolates of MDR and XDR-TB, suggesting little cross-resistance with currently used medications. In comparison, compound 28 (cLogP: 8.51) exhibited a slightly higher cLogP value than 21 (cLogP: 7.89) due to the introduction of a lipophilic silicon atom. Furthermore, 1,2,4-triazoles 28 could directly bind to the Msmg MmpL3 in MST assay. Overall, these identified 1,2,4-triazole containing antitubercular compounds hold the promise for further lead optimization.

Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

AcknowledgmentsThis work has been supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 82073706 and 22107031). This project has also been funded in part with Federal funds from the National Institutes of Health and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Department of Health and Human Services (No. AI155602).

Supplementary materialsSupplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108464.

| [1] |

World Health Organization (2022). https://www.who.int/health-topics/tuberculosis#tab=tab_1.

|

| [2] |

A.J. Nunn, P.P. Phillips, S.K. Meredith, et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 380 (2019) 1201-1213. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1811867 |

| [3] |

J.C. Brust, N.R. Gandhi, S. Wasserman, et al., Clin. Infect. Dis. 73 (2021) 2083-2092. DOI:10.1093/cid/ciab335 |

| [4] |

F. Conradie, A.H. Diacon, N. Ngubane, et al., N. Engl. J. Med. 382 (2020) 893-902. DOI:10.1056/nejmoa1901814 |

| [5] |

E. Chesov, D. Chesov, F.P. Maurer, et al., Eur. Respir. J. 59 (2022) 2100621. DOI:10.1183/13993003.00621-2021 |

| [6] |

A. Viljoen, V. Dubois, F. Girard-Misguich, et al., Mol. Microbiol. 104 (2017) 889-904. DOI:10.1111/mmi.13675 |

| [7] |

J.A. Delmar, T.H. Chou, C.C. Wright, et al., J. Biol. Chem. 290 (2015) 28559-28574. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M115.683797 |

| [8] |

R. Székely, S. Cole, Mol. Microbiol. 99 (2016) 831-834. DOI:10.1111/mmi.13306 |

| [9] |

J.M. Belardinelli, A. Yazidi, L. Yang, et al., ACS Infect. Dis. 2 (2016) 702-713. DOI:10.1021/acsinfecdis.6b00095 |

| [10] |

J.M. Belardinelli, C.M. Stevens, W. Li, et al., Sci. Rep. 9 (2019) 10728. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-47159-8 |

| [11] |

W. Li, C.M. Stevens, A.N. Pandya, et al., ACS Infect. Dis. 5 (2019) 1001-1012. DOI:10.1021/acsinfecdis.9b00048 |

| [12] |

K.A. Sacksteder, M. Protopopova, C.E. Barry, et al., Future Microbiol. 7 (2012) 823-837. DOI:10.2217/fmb.12.56 |

| [13] |

M.J. Boeree, N. Heinrich, R. Aarnoutse, et al., Lancet Infect. Dis. 17 (2017) 39-49. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30274-2 |

| [14] |

S. Borisov, E. Bogorodskaya, G. Volchenkov, et al., Tuberculosis Lung Dis. 96 (2018) 6-18. DOI:10.21292/2075-1230-2018-96-3-6-18 |

| [15] |

M.B. McNeil, G.M. Cook, Antimicrob. agents CH. 63 (2019) e00629-00619. |

| [16] |

B. Zhang, J. Li, X. Yang, et al., Cell 176 (2019) 636-648. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.003 |

| [17] |

M. Shao, M. McNeil, G.M. Cook, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 200 (2020) 112390. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112390 |

| [18] |

M.D. Umare, P.B. Khedekar, R.V. Chikhale, ChemMedChem 16 (2021) 3136-3148. DOI:10.1002/cmdc.202100359 |

| [19] |

R. Ramesh, R.D. Shingare, V. Kumar, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 122 (2016) 723-730. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.07.009 |

| [20] |

J. Stec, O.K. Onajole, S. Lun, et al., J. Med. Chem. 59 (2016) 6232-6247. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00415 |

| [21] |

G. Poce, M. Cocozza, S. Alfonso, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 145 (2018) 539-550. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.12.075 |

| [22] |

M.S. Scherman, E.J. North, V. Jones, et al., Bioorg. Med. Chem. 20 (2012) 3255-3262. DOI:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.03.058 |

| [23] |

Z. Gil, N. Martinez-Sotillo, A. Pinto-Martinez, et al., Parasitol. Res. 119 (2020) 649-657. DOI:10.1007/s00436-019-06560-y |

| [24] |

Z.J. Liu, X.Y. Guo, G. Liu, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 27 (2016) 51-54. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.11.001 |

| [25] |

M. Biava, G. Porretta, G. Poce, et al., J. Med. Chem. 49 (2006) 4946. DOI:10.1021/jm0602662 |

| [26] |

G. Poce, R.H. Bates, S. Alfonso, et al., PLoS One 8 (2013) e56980. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0056980 |

| [27] |

S. Bhakta, N. Scalacci, A. Maitra, et al., J. Med. Chem. 59 (2016) 2780-2793. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00031 |

| [28] |

H. Zhao, Y. Gao, W. Li, et al., J. Med. Chem. 65 (2022) 10534-10553. DOI:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.2c00718 |

| [29] |

G. Poce, S. Consalvi, G. Venditti, et al., ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 10 (2019) 1423-1429. DOI:10.1021/acsmedchemlett.9b00204 |

| [30] |

S. Zhang, Z. Xu, C. Gao, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 138 (2017) 501-513. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.06.051 |

| [31] |

A. Sharma, A.K. Agrahari, S. Rajkhow, et al., Eur. J. Med. Chem. 238 (2022) 114454. DOI:10.1016/j.ejmech.2022.114454 |

| [32] |

P.Z. Zhang, S.F. Zhou, T.R. Li, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 23 (2012) 1381-1384. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2012.10.024 |

| [33] |

J.N. Sangshetti, F.A.K. Khan, R.S. Chouthe, et al., Chin. Chem. Lett. 25 (2014) 1033-1038. DOI:10.1016/j.cclet.2014.04.003 |

| [34] |

P. Thirumurugan, D. Matosiuk, K. Jozwiak, et al., Chem. Rev. 113 (2013) 4905-4979. DOI:10.1021/cr200409f |

| [35] |

A.K. Agrahari, P. Bose, M.K. Jaiswal, et al., Chem. Rev. 121 (2021) 7638-7956. DOI:10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00920 |

| [36] |

W.C. Tseng, L.Y. Wang, T.S. Wu, et al., Tetrahedron 67 (2011) 5339-5345. DOI:10.1016/j.tet.2011.05.003 |

| [37] |

L. Collins, S.G. Franzblau, Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41 (1997) 1004-1009. DOI:10.1128/aac.41.5.1004 |

| [38] |

O.K. Onajole, M. Pieroni, S.K. Tipparaju, et al., J. Med. Chem. 56 (2013) 4093-4103. DOI:10.1021/jm4003878 |

| [39] |

R. Ramesh, D.S. Reddy, J. Med. Chem. 61 (2017) 3779-3798. |

| [40] |

S. Lun, H. Guo, O.K. Onajole, et al., Nat. Commun. 4 (2013) 2907. DOI:10.1038/ncomms3907 |

| [41] |

T.R. Ioerger, S. Koo, E.G. No, et al., PLoS One 4 (2009) e7778. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0007778 |

| [42] |

N.N. Wang, J. Dong, Y.H. Deng, et al., J. Chem. Inf. Model. 56 (2016) 763-773. DOI:10.1021/acs.jcim.5b00642 |

2024, Vol. 35

2024, Vol. 35